The Canadian assault on Juno Beach was the most successful of the Allied landings on D-Day. By nightfall, the 3rd Canadian Division was on its interim objective eight kilometres inland (code-named ELM), with some formations well beyond. Early the next afternoon, the 7th Brigade established itself astride the Caen-Bayeux highway at Bretteville-l’Orgueilleuse and Putot, becoming the first Allied formation to capture its ultimate D-Day objective. The 9th Brigade was not so fortunate. As it advanced on D+1 towards its final objective of Carpiquet airfield west of Caen, the vanguard was ambushed by two battalions and about forty tanks from the 12th SS Panzer Division (Hitler Youth). British 3rd Division advancing on the Canadians’ left was struck at the same time. This was just the first of a wave of counter-attacks by three German Panzer divisions that broke against the Anglo-Canadian defences over the next four days. By June 11, the 3rd Canadian Division was a spent force. As the reserve brigade, the 8th played no direct role in blunting these assaults. Its job through the rest of June was to hold the line. For the men of the North Shore, that meant almost four weeks of continuous contact with the enemy.

As with all the other Allied troops who landed on D-Day, the NSR’s first night ashore was anything but restful. Sporadic fighting went on everywhere as patrols clashed, isolated German garrisons attempted to escape, officers tried to locate their units, and supply columns got lost. Amid this confusion, virtually all of the 285 prisoners captured by the NSR on D-Day escaped. At Tailleville the firing went on throughout the short hours of a Normandy summer night. During those few hours of darkness, the regiment was bombed by the German air force, and mortared and sniped at, while a steady stream of parachute flares and anti-aircraft tracers lit up the sky. Morning brought relief only from the pyrotechnics, as the grim business of war continued in earnest. As the day brightened, Padre Hickey and others buried the dead who still lay all around from the previous day’s fighting, and Lieutenant-Colonel Buell mustered the battalion for the unfinished business from D-Day: the attack on the radar station at Douvres. In the event, the North Shore was the only Canadian battalion still fully engaged in combat in the beach zone throughout D+1.

Buell must have been anxious about the prospect of tackling the radar station on June 7, for the twenty-five-acre radar complex was a formidable position: it was the largest radar station in lower Normandy. The northern section of the station, which Lieutenant Moar’s platoon had probed on the afternoon of D-Day, housed a huge long-range early warning radar with a massive antenna protected by three 20-mm antiaircraft guns, concrete positions, trenches, and belts of wire. The main site, across the road to the south, was four times bigger and held the two medium-range and two short-range radars used to direct night fighters. By the end of D-Day, the antennas and the surface of the station were in utter ruins from hours of pounding by warships and aircraft. What was not seriously damaged were the thirty concrete defensive works, minefields, anti-tank ditch, extensive wire, and massive, five-story-deep steel-reinforced underground headquarters structure. Apart from the radar equipment, these emplacements held dual-purpose anti-aircraft and ground defence 20-mm and twin machine guns, heavy mortars, five 50-mm anti-tank guns, and at least one 75-mm field howitzer, all encased in concrete. Despite this formidable arsenal, Allied intelligence estimated that the station’s garrison, 8 Company of Luftwaffe Regiment No. 53, would have “no stomach for a fight” after the bombardment on D-Day. They were, of course, quite wrong. Indeed, by D+1 the garrison had been reinforced by the remnants of the 716th Division and numbered at least 230 men, and possibly more.

Buell’s orders at the end of D-Day were to contain the station and take it on D+1. Before he could attack, the North Shore had to clear the start line along the woods south of Tailleville. And so, at 0700 on June 7, a much depleted A Company, now at three-quarters strength under its new acting commanding officer, Captain J.L. Belliveau, began securing the woods. Once this was complete, C and D Companies would pass through and set up for D Company’s attack on the radar station. In the end, things never got that far.

The forested area south of Tailleville covered about thirty acres, and A Company found it filled with Germans and “honeycombed with trenches.” It was, in reality, the headquarters for German artillery in the area. Unable to use artillery support because of the tree cover, Belliveau’s men found clearing the woods very slow going. As the morning wore on, Buell grew impatient and sent his intelligence officer, Captain Blake Oulton, forward to see what the problem was. “It was slow work,” Oulton recounted later, “with so many trenches and prepared positions to be ferreted out.” Eventually, Buell undertook his own reconnaissance. Jumping into Major Bill Bray’s tank, and screened by a troop and a half of other Fort Garry Shermans, Buell was driven to the southern end — “the German end,” in Buell’s words — of the woods. There Buell and Bray dismounted to get their first real look at the radar station. “To my amazement,” Buell said, “there seemed to be a steady stream of [German] troops moving from Douvres-la-Délivrande into the radar station.” It seems that as the British 3rd Division closed the gap between themselves and the Canadians, many Germans still left along the coast sought refuge in the radar station.

Buell also found many of the enemy still in the wooded area, so he ordered C Company to join the fighting alongside A. If all this was not enough, the battalion once again came under sniper fire in Tailleville. The North Shore’s strength was being rapidly dissipated. One platoon of B Company was still in St. Aubin and was not retrieved until 2100 hours that night, while the rest of that company formed the battalion reserve. D was slated for the attack on the radar station, and A and C were mired in the Tailleville forest. Just how many Germans caused all this trouble remains unclear: the NSR captured only a handful. It is generally accepted that most fled to the west and were corralled by other Canadian troops around Basly. Meanwhile, the 105-mm field guns of the 19th RCA fired on the radar station to keep it busy, as did the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa’s heavy machine guns and mortars that were still attached to the NSR.

It was not until 1600 hours that the forested area was clear enough for Buell to start reorienting his battalion for the attack on the radar station. Major Anderson’s D Company would lead the assault on the left, but his men would now be joined by Major Daughney’s C Company on the right, in a two-company assault. When the two majors came forward with Buell to get their first glimpse of the station, they were, in his words, “much impressed by the size and strength” of it. No doubt. When the commander of 19th RCA came forward to discuss artillery support for the attack, he could offer them nothing to allay their concerns. The leading elements of the 9th Brigade, making the last dash to their objective at Carpiquet, and British forces to their left had been attacked several hours earlier by the 12th SS Panzer Division (Hitler Youth). Intense mortar and machine-gun fire from the radar station had already delayed artillery support for the struggling 9th Brigade by forcing 14th RCA from its gun positions near Basly. The only big guns available, the nine 6-inch guns of the cruiser HMS Belfast (the equivalent of a medium artillery battery), were dedicated to stopping the Hitler Youth. The NSR would have to make do with the twenty 105-mm guns of the 19th, its own mortars and a few 4-inch mortars from the Camerons. Most had already seen the affect this was having on the steel-reinforced concrete of the radar station’s positions. In Padre Hickey’s words, firing 105-mm shells at the station “was like blowing soap bubbles against Gibraltar.”

If this was not enough to give Buell pause, the fate of C Company and a Churchill AVRE probably was. As the NSR prepared for the attack, a British engineer arrived and enquired of Major Forbes what the problem was. When told, the Englishman said “Well, well, we’ll soon fix that!” and then turned and shouted “Bring up the Petard!” In due course, along came a Churchill AVRE, its petard mortar in the turret loaded with a huge shaped charge explosive that was designed to destroy concrete emplacements. Despite the warnings of Forbes and others, the British major jumped in the vehicle and it rumbled towards the radar station. Within seconds the Churchill was completely destroyed in a powerful explosion. After that “Bring up the Petard!” became a cliché in the NSR. Meanwhile, when C Company moved to the start line it came under intense fire from the radar station and had to retreat into the woods.

With that Buell decided the radar station was well beyond the capabilities of his battalion, although he hesitated slightly when the rest of the squadron of Churchill AVREs arrived. After consultation with brigade headquarters, however, the NSR were ordered to move west of the wooded area at 1800 and join the rest of the brigade in their positions around Anguerny. The enormous challenge of taking the radar station with a weak battalion and little fire support may well account for Buell’s caution on June 7. It is clear that he was not prepared to commit the NSR to heavy losses taking the woods, nor could he afford to if he had any hope of tackling the station. In the event, the NSR suffered only eighteen casualties on D+1, and the job of tackling the radar station passed to the newly arrived 51st Highland Division.

Now came the final indignity of a frustrating day. Before the NSR could move off from its newly won positions in the Tailleville woods, it was attacked by the British Army’s 5th Battalion Black Watch and its supporting tanks. In fact, the battalion was still in the forest when, as Lieutenant W.K. Dickie of D Company recalled, it “immediately came under heavy fire from machine guns and tanks” to its rear. Major Anderson discovered the problem when most of D Company simply went to ground, while his forward platoon and C Company bolted south over open ground. Anderson ran out and stopped the tank fire, but the Black Watch “fought” their way through the woods despite his pleas. “I fully expected to find few of our men alive.” Anderson said. But casualties were light, just several wounded. The Black Watch desperately wanted to come to grips with the enemy and had little time for anyone in their way. Nor were they interested in the information that Buell and his officers could provide.

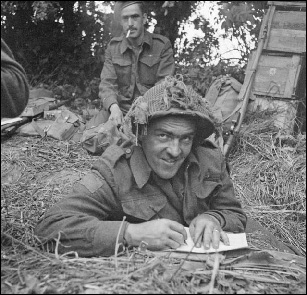

Writing home. Anguerny, June 8, 1944. LAC PA-132800

While the North Shore moved off towards Anguerny, Blake Oulton and several others stayed on to watch the British attack on the radar station. It opened with three Churchill AVREs moving forward, all of which were destroyed in quick succession. As Oulton commented, “The Black Watch never moved out of the woods to the positions we had taken.” The Highlanders soon passed the station on to the 4th Special Service Brigade of the Royal Marines, who took another ten days to capture it. In the meantime, the radar station at Douvres was a thorn in the side of the Anglo-Canadian beachhead, and with its secure communications (including buried telephone cables) and excellent observation kept the Germans informed of events behind the Allied lines. It is tantalizing to think what might have been accomplished had the NSR been able to take the position quickly on D-Day.

By late in the day on June 7, the NSR were reunited with their brigade in the fortress position around Anguerny. The rest of 8th Brigade had spent the day cleaning up pockets of resistance and German stragglers behind the front and securing the divisional reserve line. The North Shore remained around Anguerny for the next three days, and it was here that the battalion was restored to nearly full strength. Lieutenant “Bones” McCann and his platoon rejoined the battalion from St. Aubin after a harrowing nighttime trip that accidentally led them to the perimeter of the radar station. The first batch of reinforcements, three junior officers and eleven men, also stumbled in on the eighth. They had landed on D-Day on the other side of Courseulles-sur-Mer and were detained briefly by the Chaudières as reinforcements.

At 0100 hours the next day, a further four officers and sixty-nine men arrived. They, too, had landed on D-Day with much difficulty. When their LCT ran aground and could not be moved, the men elected to wade to the beach through water that was well over many of their heads. Undeterred and heavily burdened by their equipment, a few of those too short to keep their heads above water used their rifles as a breathing tube and walked ashore submerged. Three drowned in the process. It took them most of two days to find the battalion, but the arrival of nearly one hundred men and some officers on the eighth did much to restore the NSR’s fighting strength. The battalion’s quartermaster, Sergeant E.J. Russell, and some of its supporting trucks and supplies also caught up with the NSR at Anguerny.

Like the others, they too had a terrible time just getting ashore. Unable to land on the sixth because of congestion at Bernières, they came ashore the next day, but their Landing Ship, Tank — a huge vessel of 5,000 tons with two decks and giant bow doors that opened like a clamshell — ran aground three hundred metres offshore. The first vehicle to drive out simply dropped off the ramp and got stuck nose first on the bottom. It had to be winched out with a cable. The larger trucks, including those of the NSR, fared better, and Russell lost only one. They assembled at their concentration point on the seventh and moved forward to the NSR positions at Anguerny the next day. Although the North Shore’s fighting echelon was now largely complete, the rest of the battalion’s support and administrative elements did not land until late June.

Foot care, a constant preoccupation for infantry. Anguerny, June 8, 1944. LAC PA-190907

While the North Shore was dug in around Anguerny, the battle with the 12th SS raged along the 7th and 9th Brigade fronts south of them. Only once, on the night of June 8/9, did elements of the Hitler Youth — in the early days mistaken by most Canadians for paratroops because of their camouflage uniforms — reach the NSR position. On that black night, as Lieutenant McCann recalled, “a handful of Jerry paratroopers, youngsters not more than seventeen years old” stumbled onto B Company. What alarmed the North Shore most was that all the young Nazis seemed to be carrying Canadian service revolvers — evidence, had they known it, of the over-running of two companies of The North Nova Scotia Highlanders at Authie the day before. In a short time, the North Shore men would have cause to fear and loath those teenagers in the mottled camouflage suits.

As the battle west of Caen settled down into a struggle for position, the 8th Brigade was drawn into the gap between the two front-line brigades that ran along the Mue River. On June 9, the NSR slipped forward slightly to occupy positions vacated by the QOR. Late on the tenth, the warning came to be ready to move. At 0730 the next day, on a clear but cool morning, the North Shore shifted their position to Cairon, going into the line to the right of the 9th Brigade. The early morning march through the fresh Normandy countryside left a lasting impression on Padre Hickey, and probably on many of the deeply religious Catholics of the NSR who took comfort in the “calvaries at the crossroads that seemed to come to life in the breaking dawn.” The more literate among them would no doubt have seen the symbolism in the larks that darted amid the trees along the roadside and the bloodred poppies that lined their route.

The NSR settled into Cairon, sent out patrols, and started drawing fire from the enemy. Meanwhile, the rest of 8th Brigade was employed in limited attacks. The Chaudières and 46 RM Commando, supported by tanks, wrestled the Hitler Youth for the village of Rots in the wooded valley of the Mue River. Its capture closed the gap between the 9th Brigade in the east and the 7th Brigade in the west. The QOR were temporarily attached to the 7th Brigade. On June 11, they were ordered to push the Canadian line south of Bretteville and Putot to the high ground around the village of le Mesnil-Patry. This attack was, in the words of Queen’s Own history, an operation “conceived in sin and born in inequity.”

The attack on le Mesnil-Patry was mounted in haste, but it was not without purpose. By D+4 there was still a gap in the German front lines south of Bayeux, and the British planned to push their 7th Armoured Division through it. British 50th Division, to the right of the Canadians, was attacking in support of this operation and a concerted push south of Putot/Bretteville would help them. So D Company of the QOR was ordered to join up with B Squadron of the 1st Hussars from Montreal and attack across two kilometres of open ground to le Mesnil-Patry. This was the first phase of a two-stage operation towards Cristot. Despite the protests of their officers, the battle group was given no time to reconnoiter the area, discuss the situation with the troops in the forward positions or to tee-up fire support. Nor had the QOR ever trained or operated with the 1st Hussars. Regardless of all this, at 1400 D Company and B Squadron of the 1st Hussars drove through the 7th Brigade lines at Norrey without ever stopping — and into the waiting guns of a full battalion of the 12th SS and their supporting tanks. The result was a slaughter. Up to that point, D Company had suffered only thirteen casualties. Of the 105 men who rode into battle on June 11 at le Mesnil-Patry, ninety-six were killed, wounded, or captured. Only nine escaped uninjured. B Squadron of the 1st Hussars was virtually wiped out, suffering eighty men killed or wounded. Phase two never got started. The NSR was never part of the fiasco at le Mesnil-Patry, but it later got the unenviable duty of clearing the battlefield.

For five days, the North Shore held the line near Cairon and Lasson, patrolling, sniping, digging, and being shelled. At Cairon the Germans had excellent observation over the NSR’s positions: consequently, no matter where they moved, the shells found them. Several men were killed when shells burst in tree tops, sending the blast down into their trenches.

The exposed position at Cairon produced a steady drain of casualties: two killed on the tenth, four on the eleventh plus eight injured, and three more dead on the twelfth. One of those killed at Cairon was Corporal Howie Aubie of the carrier platoon, the composer of the regiment’s unofficial march, “The Old North Shore.” When Captain Belliveau, the acting commander of A Company, was wounded, Major Anderson was shifted from D Company to command A, while Captain Clint Gammon was promoted and took over D Company.

The move to Lasson-Rosel in the Mue valley brought relief from the constant shelling, although Major Daughney narrowly escaped death on a patrol when a bullet penetrated his helmet and creased his forehead. Others were killed on patrols or died when the German air force again bombed them. But the greatest moment of panic came when A Company reported a tank assault on the morning of the fifteenth. The warning rebounded throughout the whole brigade and everyone — even the cooks — stood to. The tension only eased when the brigade discovered that A Company was actually in reserve, and on further examination the tanks turned out to be a heard of cows, in Will Bird’s words, “ambling down a pasture trail.”

The North Shore were ordered forward to le Mesnil-Patry late on the seventeenth. Major G.E. Lockwood, the second in command, and Lieutenant Oulton, the intelligence officer, had already done a reconnaissance, arranging the takeover from The Royal Winnipeg Rifles, who had just occupied the position. “Dark came and we started off,” Father Hickey wrote in his memoir, “through Bray and Brettevillel’Orgueilleuses (Bretteville The Proud), now a heap of ruins with only a gaunt shell-pierced church tower left to tell you of its former pride. You could smell death in the air; and, when the moon came up, you could see dead bodies along the roadside.” It only got worse. “On crossing the rail at Putot-en-Bessin we were assailed by the most offensive stench of the dead,” Oulton remembered. “On that battlefield along with the dead soldiers of opposing armies there were scattered the carcasses of many cattle and horses lying bloated in the hot sun. German and Canadian tanks were all about, knocked out hulks. There were sixteen Sherman tanks lying almost in line abreast before the village where they had been shot up.” It was a scene from hell, and some of the Winnipegs “were quite jittery” when the NSR arrived just before dawn.

They had every reason to be jittery. The Canadians were still facing the fanatical Hitler Youth of the 12th SS, who by this stage had shot nearly 150 Canadian prisoners, many of them from the RWR. When Fred Moar arrived at le Mesnil-Patry, he saw a line of dead officers from the QOR assembled along the road as if for medical treatment. Each one had a bullet through the head. “I knew them all,” he recalls with profound sadness. Burial parties were organized by Lieutenant Bernard McElwaine and Sergeant Mike Sullivan of the pioneer platoon. All afternoon and early evening on the seventeenth, narrow graves were dug, caps removed, and silence observed as Father Hickey said a few words over small groups of bodies. An armoured bulldozer was brought up from the beach to scrape a long trench and push as many of the animal carcasses as possible into it. It took days for the smell to subside — or for the men to become accustomed to it — and in the meantime some were so ill they had to be evacuated temporarily.

Buell deployed three companies along the southern edge of the village: A on the left, D in the centre, and C on the right, with B in reserve and battalion HQ tucked safely into a stone barn on the north side. For the next ten days, le Mesnil-Patry was home to the NSR. And although it was well forward, under fire, and subject to constant probing by German patrols, the village had its compensations. The most important of these was food. As Father Hickey recalled, “Only one little animal was safe, the sheep.” After years of living on mutton in Britain, the men wanted nothing to do with sheep. But le Mesnil-Patry abounded in cattle, chickens, and ducks — and horses if your taste ran to that. As Hickey observed, no one from the NSR “would stoop to mutton, with steaks and pork chops walking around.” Even after the army issued a strict order prohibiting living off the land, le Mesnil-Patry, with its minefields and snipers, produced a bounty. Indeed, cattle had a habit of blowing up on German minefields and revealing their presence, and for that reason the Germans tried to shoot them. Either way, there was a lot of beef available. The day the order came down to restrict themselves to army rations, June 21, 1944, Lieutenant McElwaine dined on roast duck and pig liver, and two days later, enjoyed twenty-five-year-old cognac and steak for breakfast. Milk and eggs simply had to be collected. When Major Gammon was invited to dine with Lieutenant E.T. Gorman’s platoon one evening, he arrived to find a barn door covered with a cloth and stacked high with steak, potatoes, carrots, pickles, and chow. Music played in the background from a scrounged gramophone. The only thing that marred the evening was a spent tank round that came through the roof and knocked down a beam while they were having tea.

During its stay in le Mesnil-Patry, the NSR was barely five hundred yards from the German positions. They exchanged fire routinely and their patrols fought one another. Fred Moar got fed up with spending all day in his slit trench and rolled out onto the grass for a bit of sunlight; but one well-placed shot ripping over his head drove him back into the ground. When Captain Phillip Oland of Saint John arrived as a new FOO from the12th RCA, his first shot wounded or killed four Germans — they were seen to fall and were carried away. In response, the Germans knocked the roof off Oland’s observation post, wounding two of his men. Generally, artillery or mortar fire drew retaliation on the infantry positions opposite. Lieutenant-Colonel Freddie Clifford, commanding officer of the 13th RCA, found that the best way to stop the enemy artillery from firing was to fire at their infantry and get them to tell their own people to stop. Oland learned this at le Mesnil-Patry from the NSR, who preferred it if the big guns remained silent while it was in the line.

The really dangerous work was done on patrols, and by all accounts the men of the North Shore were good at this very risky job. “Unless one has led night patrols in a weird and utterly strange no man’s land,” according to Lieutenant C.F. Richardson, “the feelings are hard to describe.” On the night of the nineteenth, Richardson led a patrol that slithered along a tank track in the wheat field separating the two sides. When a German patrol appeared on the other track going the opposite way, Richardson and his men went dead still and let them pass. On that patrol the only serious incident occurred while trying to get back into the NSR position. The sentry refused to accept their password and threw a grenade which bounced off Richardson before exploding. One man was wounded and Richardson’s “beret and tunic were shredded,” but he was not hurt. According to Will Bird, Lieutenant Paul McCann had “an uncanny knack of finding his way about” while on patrol, and Blake Oulton noted McCann’s “coolness in going out and coming back off patrols,” seldom armed with anything more than two hand grenades.

Six 3-inch mortars, like the one seen here being fired in training by an unidentified 3rd Division unit just prior to D-Day, gave the infantry battalion its own integral fire support. The ten-pound bomb had a range of 1,600 yards. LAC

The rate and intensity of patrols increased starting June 20 in anticipation of a major British offensive, Operation Epsom, designed to sweep west of Caen and seize the high ground of Hill 112 across the Odon River. On that day Lieutenant-Colonel Buell escorted a British brigadier around the battalion area, and the next day officers of the British 15th Scottish Division arrived to see the ground over which they would attack. The activity was noticed by the Germans, who responded with increased shelling, prompting the commander of the British attacking corps, General R.A. O’Connor, to write on the twenty-fifth to thank 3rd Canadian Division for its help and to apologize for any casualties caused.

Starting on the twenty-fourth, the NSR and the rest of 8th Brigade began a series of fighting patrols to unsettle the Germans, deny them freedom of movement, and screen the deployment of the 15th Division behind the brigade. The patrol orders for the night of June 24/25 required that one platoon — over thirty men — commanded by an officer be sent out. Its task was to capture enemy prisoners so that the formation opposite could be identified, kill “as many of the enemy as possible,” pinpoint “any enemy strong pts [points] that can be subsequently engaged by arty [artillery], 4.2” mortar, M.M.G.s [medium machine guns] or bn [battalion] weapons,” and finally generally harass the enemy. Two fighting patrols went out that night, one platoon led by McCann that brought back information and another led by Lieutenant R.V. Wilby that found a large German working party and called down artillery fire on it. On the next day, the twenty-fifth, the British 49th Division on the NSR right began a local attack, and another fighting patrol went out that night.

Finally, at 0719 on the morning of June 26, the leading elements of the 15th Scottish Division passed through the North Shore to launch Operation epsom. Ten minutes later, eight hundred guns of the 2nd British Army opened fire, the earth trembled, and, barely two hundred yards ahead of the NSR forward companies, the supporting barrage fell. The battalion’s War Diary described it as “the greatest artillery barrage yet to be laid down” in Normandy. Some rounds fell short, and at least one NSR soldier was killed. “The shells seemed to come right at us for about ten minutes,” said Clint Gammon, “and as soon as the barrage lifted the attackers went through us with their tanks on the flank. It was all over in an hour. The Germans were either killed or retreated.” The anticipated German counter-barrage did not arrive until 1120. Until then, Father Hickey and Doc Patterson went forward to help with the British wounded and returned when shells began to land amid their own men. Fortunately only a few were wounded. Later, Buell sent some of his men to have a look at the German positions. They found the bunkers piled with dead. “The slaughter had been terrible,” Gammon recalled. The NSR did find one wounded German with no fight left in him. Gammon gave him a cigarette and sent him back to the NSR lines in his jeep.

Operation Epsom, launched by British VIIIth Corps, lasted from June 26 until June 30. It gained a foothold across the Odon River and briefly held the heights at Hill 112 overlooking Caen. But savage counter-attacks by three Panzer divisions and elements of three others stalled the attack at great cost: 4,020 British soldiers killed, wounded, or missing in three days of brutal fighting. The only saving grace of the battle was the destruction of the German counter-attack launched on the Epsom salient by 2nd SS Panzer Corps, the force the Germans had been assembling for their own attack. More importantly for the NSR, as the Canadians slipped forward to cover the flank of the advancing British, it was now facing Caen: the ultimate D-Day objective of 2nd British Army, just a few short kilometres away across a flat plain.

Long before the Epsom battle collapsed on the barren and fire-swept slopes of Hill 112, the North Shore was heading into reserve. They had been at le Mesnil-Patry for ten days and suffered two dead and thirteen wounded. But during their twenty-two days in the line, the new men had been integrated and the battalion had learned a great deal about war. As Will Bird observed, “Every platoon had a large crop of new faces, and promotions had placed stripes on many old hands who had had full training.” More importantly, a month of combat had taught lessons that training could never provide. As Bernard McElwaine observed after their stint at le Mesnil-Patry, “Our ears are getting tuned to off-stage noises. It saves a lot of ducking when you can tell a Jerry from one of ours.” And the men of the NSR, like all other soldiers, had learned how to turn a slit trench into a comfortable home and still keep it largely concealed from the enemy.

At 1400 hours on June 27, the North Shore left le Mesnil-Patry and the war for a few days and marched north to a rest area at Bouanville in the Mue River valley. The relief was palpable. As the sound of the guns grew faint, Padre Hickey noticed that his teeth chattered when he talked. He mentioned it to Doc Patterson, who replied simply, “So are mine; everyone’s teeth are chattering.”

The defence of Carpiquet. Mike Bechthold