EARLY YEARS: MY CHILDHOOD IN THE SMALL TOWN OF WIERZBNIK, IN THE STARACHOWICE REGION, POLAND

“THE

GERMANS HAVE

invaded Poland. They are bombing Wierzbnik. Quickly, now, gather a few things. We will go to the countryside for a few days until things settle down. The coach is waiting for us downstairs.” My father’s tone was calm but suggested an urgency that he rarely revealed. We had been following the news from Germany, of course, and how things were deteriorating there, especially for the Jews, but we were relatively far away from the chaos of Germany. We were in southern Poland in the little town of Wierzbnik. I had always felt safe in our quaint town, insulated. Don’t all nine-year-olds feel unassailable? Or perhaps my parents had sheltered us from big, grownup issues. I was raised with a sense of continuity. Generations of Jews, including my family, had lived and died in Poland, and I assumed as much for myself.

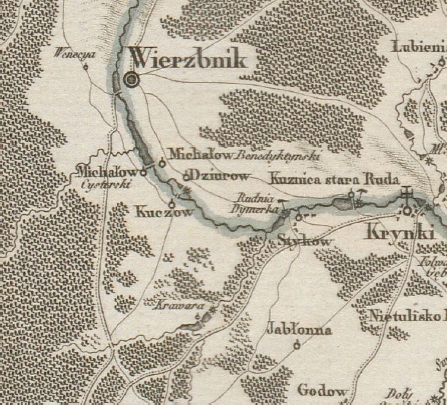

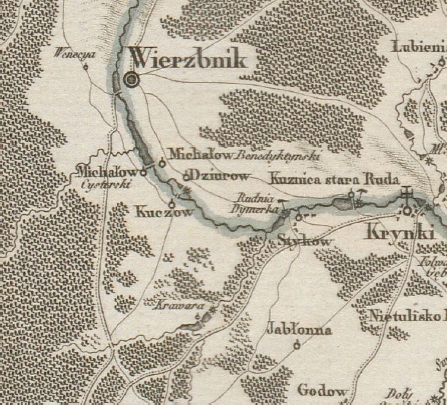

Wierzbnik, located in the Starachowice region, was founded in 1624 as a mining and metallurgical settlement. Until the early 1800s, the area was inhabited by the Cistercian monks of Wachock, who built a blast furnace in 1789. The Starzechowski family owned a forge built near the Kamienna River, a tributary of the Vistula River. As the population increased, weekly markets and annual fairs expanded. In the 1800s, the area continued to serve as a center of metallurgy, with iron foundries, ore mines, and a smelting furnace. The area was surrounded by dense forests and rolling hills, so lumberyards, sawmills, and a plywood factory were built in the vicinity. The late 1800s also saw the construction of a railway line linking the town to larger cities.

Life in Eastern Europe, where there has always been an undercurrent of anti-Semitism, has never been easy for Jews. The local population became wary of the growing Jewish population. Perhaps the majority felt threatened by the Jews’ ingenuity, tenacity, and success, or perhaps their fears were just age-old xenophobia. The Jewish population was different, spoke a peculiar language, ate unfamiliar food, kept unknown traditions, such that in 1862, a decree was issued denying Jews the right to reside in Wierzbnik-Starachowice proper. Despite these early acts of anti-Semitism, the thriving Jewish community played an important role in the development of local industry and found success in business, education, and other professions. There were doctors and dentists, veterinarians and pharmacists, as well as a community of Jewish traders, peddlers, and skilled, prosperous workers. There were cattle dealers and tailors, leather workers and shoemakers, upholsterers and hat-makers, watchmakers and photographers, carpenters, kosher butchers, bakers, bankers, printers, and blacksmiths. There were companies specializing in textiles and construction, along with brickyards, transporters, beerhouses, and a distillery—all a testament to a burgeoning community that maintained a reasonable expectation for a bright future. An address book from 1930 lists my grandfather, Chaskel, as a tinsmith.

After the financial ruin of Germany in the wake of World War I, Hitler’s nationalism appealed to an ever-broadening base, and what had sometimes been a subtle form of anti-Semitism was becoming more and more open and acceptable by society at large. Even though Jews had fought in the armies of Germany, Poland, and other countries during World War I, Jews were once again becoming an easy scapegoat on which to lay blame for Germany’s woes. The situation for European Jews had always been tenuous, and whatever success they had achieved remained vulnerable.

Starachowice was at various times part of the Austrian and part of the Russian Partitions of Poland, but Poland regained independence in 1918, and by 1920, Starachowice was considered a major industrial center with the establishment of arms, artillery, and ammunition factories and ironworks facilities. The town of Starachowice was not actually established until April 1, 1939, when Wierzbnik merged with the settlement of Starachowice Fabryczne and the village known as Starachowice Gorne. The new town was known as Starachowice-Wierzbnik.

During the summer of 1939, my mother, my brother, and I traveled by train, leaving from the station at Skarzysko to Rabka Zdroj, between Krakow and Zakopane, to the mountains for a one-month vacation. Rabka, in a valley on the northern slopes of the Gorce Mountains with natural springs, is where the Rivers Poniczanka and Slonka intersect with the Raba River. Beginning in the latter half of the 19th century, Rabka became known for its salt works, and a children’s treatment center specializing in hydrotherapy. It was also a popular spa destination in the 1930s, especially for Jews. My brother, Chaskel, was extremely skinny, and a doctor advised my mother to take him to Rabka to gain weight.

The Germans were closing in on Poland, but we were isolated, and news was scarce, so for that one month, my mother, my brother, and I shared a blissfully normal childhood summer experience. We went to the parks, rode horses, dressed in traditional Polish costumes, and took photographs. We enjoyed each other’s company, and the tranquility of the countryside. We celebrated my ninth birthday. We did not know that it would be the last summer of peace for our family, for all of Poland, and for the world.

Perhaps my parents had a sense of the impending upheaval and tried to provide us with some sense of normalcy before the advent of war. They could not have fathomed the nearly total destruction of our culture, religion, country and shtetl

. Perhaps when my mother, brother, and I were enjoying our time together in the mountains, my father was getting his affairs in order. If so, he did not let on to Chaskel or me. These were adult matters, and there was no need for children to involve themselves. My father eagerly awaited our return, and met us at the train station in Skarzysko, twenty miles from our home.

Even if my parents had been making preparations for changes that a war would bring, they did not discuss these adult matters with Chaskel or me. My grandparents told us stories about World War I, but no one could have imagined the horrors that lay ahead.

The ominous voice emanating from the radio recommended preparing for war. Two days later, on Friday, September 1, 1939, the Germans invaded Poland and reached our small town within a few days.

As the war began, we departed the town in a horse-drawn carriage. We initially thought the tanks rolling into Wierzbnik were English. We soon learned the horrible truth: they were German. As the horse and carriage clip-clopped along, the town of Wierzbnik disappeared behind us as we traveled to a farm in the countryside. Approximately eight kilometers away was a tiny settlement not appearing on any map. My grandparents called it Seszaw. My maternal grandparents, Maier and Ruchel Dawidowicz, had once owned property nearby and had gotten to know some of their Polish neighbors. My grandparents did not work the land themselves, but leased it to farmers. My grandfather, nicknamed Maier Seszaw, for the area in the countryside where my grandfather had his land, was in the business of brokering the purchase and sale of farm products and livestock, which he bought from Polish farmers and sold to Jewish butchers when he traveled into town, which he did at least twice a week. He was resourceful and entrepreneurial. He owned a horse and buggy and sold cloth and textiles and feathers for making pillows and comforters for the long Polish winters.

As the father of eight children, he built a large residential building in town with eight separate apartments, one for each of his children. On the ground-floor level were two storefronts, one for my grandfather, and one for his only son, my uncle Moishe.

When I was six years old, my grandparents sold their property in the countryside and moved to Wierzbnik full time. They lived at 53 Kolejowa Street, (Street of the Train), a few doors down from our house at 31 Kolejowa Street. The Street of the Train was not directly fronting the market square, but was a main artery in town with residential and commercial properties linking the main area of town with the train station, a vital link to the outside world, facilitating the exchange of people and goods.

My extended family was the circle of love that raised me, protected me, and taught me, especially about living Jewishly. But not all my family remained in our little corner of the world.

After World War I, my grandfather Maier’s siblings and families emigrated to America. Two brothers settled in Canada, one brother went to New York City, and one sister went to Detroit. According to my grandfather Maier, “the new world of North America wasn’t kosher enough,

” and to his great misfortune, he refused to join his siblings.

After the Germans invaded Wierzbnik, we stayed at the farm for just a few days. We had escaped to the relative security of the countryside. We later learned that the Germans did not want to conduct a massive bombing offensive in Starachowice, as the munitions factories were located there, and they knew these factories could be strategically vital to the war effort.

The war had arrived on our doorstep. We were no longer its neighbor. We were thrust into it, and it was thrust upon us. But who was this charismatic leader of Germany, the Fuhrer, who had whipped the populace into an anti-Semitic frenzy?

“When Jewish blood spills from the sword, all goes twice as well,” Hitler declared. His anti-Semitic feelings were widely known. In 1920, Hitler wrote an article, “Why We Are Against the Jews.” Hitler was determined to rid Germany of Jews, Gypsies, and the physically and mentally handicapped, as a way to cleanse Germany and to purify the Aryan race. In his 1925 and 1926 publications of Mein Kampf,

he set out his hateful ideological program, stating that the Jews and the Bolsheviks were racially and ideologically inferior, even threatening, and encouraging a German revolution by the superior Aryans and National Socialists. His stated goals included the expulsion of the Jews from Germany and the unification of German people into one Greater Germany. Too many dismissed his ideas as the work of a madman.

Religious Jews with their payos

and their traditional Hassidic garb, their isolationism, and their separation from mainstream society, were easy prey for xenophobic and disgruntled men and women who were easily brainwashed by the growing nationalistic Nazi movement. While they claimed ignorance to the goals of the Nazi regime, the population was aware of Nazism, and many openly supported their platform and believed its propaganda. There were Nazi-inspired board games and playing cards adorned with Hitler’s image. There were anti-Jewish cartoons, slogans, and placards, and punishments for those who bought from Jewish-owned stores. The destruction of the European Jewish population did not happen overnight; it began with a series of anti-Semitic writings and speeches. And despite Jews being a part of life in Germany for over a thousand years, and having recently served in the German Army during World War I, Hitler declared, in 1933, that anyone with even one Jewish grandparent could no longer work with Aryans.

On November 7, 1938, Herschel Grynszpan, a seventeen-yearold Jew who had been sneaked into France and was living with extended family so as to avoid the increasing anti-Semitism in his native Germany, shot Ernst Vom Rath, a German diplomat in the Embassy in Paris. Grynszpan’s parents and siblings were deported from Germany to Poland, along with thousands of other Jews whom Germany forced to “repatriate” to Poland. Grynszpan’s family was caught in a no-man’s land between the German and Polish borders and held in a refugee camp. Vom Rath died two days after being shot, triggering Kristallnacht

, the Night of Broken Glass, when Germans torched Jewish businesses, synagogues, books, and Torahs, beginning, in earnest, their assault on Jews in Germany.

I was eight years old on Kristallnacht

and blissfully unaware of it. If my parents ever discussed it, they were careful not to do so in front of Chaskel or me.

I was born at home on August 15, 1930, with the assistance of a midwife in Wierzbnik. My parents named me Michael (Michulek

) Baranek, but I was affectionately referred to as Michulciu

. I was the firstborn, the son of Jews from generations descended from Abraham. And just as Abraham sealed the covenant with God through circumcision, my parents fulfilled that same Jewish tradition when I was eight days old. In Europe, this was a clear way to identify a Jewish boy or man. Two years later, my brother Chaskel was born, and he too would have a bris.

My paternal grandparents were Chaskel and Leah Baranek. My grandfather, a tinsmith, passed away when I was a year old. When my brother was born a year after that, my parents named him in memory of my deceased grandfather. As was common in this era, especially among the small Jewish gene pool, my grandmothers, Leah Baranek and Ruchel Davidowicz, were distant relatives.

During the summers, my mother’s extended family spent time at my grandfather’s farm, with all the cousins and siblings. From my grandfather’s seven daughters and one son, he was blessed with sixteen grandchildren. One could only imagine the number of family members gathered around the table at a Passover Seder, had those grandchildren lived to produce families of their own, but alas only two of the fifteen grandchildren survived the Nazis, and I am one of them.

In those times, families engaged a matchmaker to bring a potential groom to meet a bride’s family. It was expensive to marry, and my grandfather had seven daughters! A woman needed to have a dowry to offer the groom. Times were changing and this custom was beginning to fall out of fashion. Only my mother’s older sisters had a shiddach

, or an arranged marriage. The younger sisters were still single. In those days, it was more prestigious to have a mid-week wedding. The ceremony always took place outside under a chuppah,

the marriage canopy, and the wedding reception was usually held at one’s home where special cooks were hired to prepare food for the wedding reception. The celebration typically included a klezmer

band, made up of a violin player, a clarinet player, a trumpeter, and a drummer. It was quite traditional. One of my aunts was married on Saturday, a “quiet wedding,” because of the many restrictions on how one could celebrate on the Sabbath. Many of these old-fashioned customs were going out of style, especially in large, modern cities, but Wierzbnik was a small, traditional town.

My father, Moszek “Moishe” Ber Baranek, a tall man with a generous nature, was a merchant in the business of buying and selling steel, hardware, building supplies, and farming equipment. He had a license to sell certain specialized items for his equipment business in the area encompassing Seszaw. He imported some materials from the town of Oswiecim, (known in German as Auschwitz). My father employed both Jews and non-Jews. As was a typical setup in Europe, my father owned a building with commercial space on the street level and residences above. He also built and owned a separate warehouse nearby. Our home was large. My mother, Chaja Dawidowicz, owned and operated a grocery store in one of the ground floor commercial spaces. Groceries were sold in bulk. Nothing was pre-packaged, and almost everything was perishable. The two most sought after commodities at the time were sugar and soap. My mother was a small woman, attractive and hardworking. She knew most of her customers and sold to them mostly on credit. She was a busy woman, running a household and a business. For country folk, my parents were making their way in the world, improving their circumstances, and beginning to elevate themselves.

The building that housed the commercial space downstairs and residences above was divided between my father and his brother, Ben Zion. On our side of the building lived my immediate family, my parents, Chaskel, and me. Our live-in Polish maid spoke Yiddish fluently, rare for a non-Jew. Above the store were two apartments that my parents rented out, one to the Rabinovich family, the other to the Gutterman family. On my uncle’s side of the building lived my uncle and his wife, Sala, and their daughter, Nacha, born in 1940, when I was ten. My uncle rented one of his spare apartments to non-Jews, also a rarity at the time.

Our town was a mix of traditional Jewish families and Catholic Poles. A church with a steeple rose high above the town. The town square was ringed with homes and businesses, government buildings, and the train station. Near our house was a small statue of Christian significance, likely honoring a saint, standing about four feet high. When there was a Catholic funeral procession, we would close our doors and shutters, not out of superstition about death, but so as not to call attention to our status as Jewish outsiders in a Catholic country. Although there was relative peace in our community between Christians and Jews, there was always an overriding awareness of us

and them

. Despite their successes and accomplishments, Jews throughout history have long known their place in society: others, strangers, outsiders.

My family worked hard and was comfortable financially. My father continually sought to better himself in many ways. His first language was Yiddish and he spoke Polish with a detectable accent, but his desire to progress in business with his many non-Jewish customers led him to hire a private tutor to help him improve his Polish grammar and pronunciation.

Wierzbnik was a shtetl

, a small town. It was not as small as some of the remote villages, where town criers announced the news, but not so large as Warsaw or Krakow, which had streetcars. Our town also had a train station, which would prove to be both a blessing and a curse for the people of Wierzbnik. The streets of Wierzbnik were lined with cobblestones. Some homes had electricity; others did not. We were among the fortunate few who had electricity, but we did not have running water or indoor bathrooms. Behind our house was an outhouse. It was a structure with three separate stalls, one for each of the living quarters within our side of the building. There was no toilet paper in those days, so people in towns used newspapers to clean themselves; however, in the countryside and on farms, people only had leaves at their disposal.

Because we had no running water, we had a few white enamel containers, two to three feet high, that we used to store well-water. Treigers

, water carriers, earned their living by transporting water for household use. Water carriers would deliver water from the well in the market square to our house a few times a week. There were other wells around town, but the one in the town square had a reputation for purity. The water carriers would draw water from the well in pails, attached to the ends of a shoulder yoke. This wooden device would rest on the water carrier’s neck and shoulders. Water was heated on the stove to use for cooking or to fill a bathtub. Typically, we bathed Thursday evenings, or on Fridays, in preparation for Shabbat. Customarily, the man of the house bathed first, followed by the woman of the house, and then the children. Water was costly and so had to be used sparingly. There was a mikve

in town, but that was only used for ritual bathing and purification, and in principle, not for hygiene. Household water was not used for cleaning clothes either, as well-water was too valuable for such use. The maid would carry the laundry to the river and clean the clothes there. We used wood and coal to heat our home and our stove. Fortunately, we had a wood or coal-burning heater in each bedroom. Poland was cold much of the year, and even during the summer, temperatures dropped at night.

One of our prized possessions was a large radio. We gathered around the radio to listen to various programs, including the weekly broadcast from Jerusalem. Often, my father would situate the radio near the window facing the street, so that others who did not own a radio could listen, too. He especially did this when it was becoming apparent that the political situation in Germany was worsening, and that war was imminent. The impending doom was palpable. We received daily copies of Jewish newspapers from Warsaw, but the deliveries ceased when the war broke out.

Life was simple during my fleeting childhood. When I was five years old, the former dictator of Poland, Josef Pilsudski, died. The Jews of Wierzbnik mourned his death, as it ended a period of relative safety and stability for Jews in Poland. Pilsudski’s regime was favorable to ethnic minorities, including Jews, because Pilsudski was more interested in an individual’s loyalty to the state, to Poland, than to any particular ethnic or religious group. Many Jews supported Pilsudski, who attempted to restrain anti-Semitic sentiment in Poland. He maintained public order, even though there were certainly anti-Semitic acts. Jews were prohibited, for example, from working in the armament factories in Starachowice. Pilsudski’s death signaled a general downturn in the stability of Jewish life in Poland. Anti-Semitism spread like wildfire across the Polish countryside – fast and unstoppable.

At the age of seven, I entered school, but only had two years of formal Polish public school education as a result of the unfortunate circumstance of the war. Chaskel received no formal education, but he did receive a Jewish education. By the time he was old enough to attend regular Polish school, Jews were already forbidden from attending.

Throughout eastern Europe, most Jews were observant; however, the Reform movement, which began in the 1800s, was taking root in more populated cities throughout Europe, especially in Germany where it began. Regardless of denomination, however, nearly every Jew kept kosher, observed the Sabbath, and studied Torah. Nearly every Jewish family sent their sons to cheder

, a school to learn Hebrew and study Torah. Cheders

were common throughout Europe. Lessons were often taught by a melamed

, a teacher. Parents paid the melamed

directly for the Hebrew and Torah classes. We often studied by the light of a kerosene lamp. The cheder

was in the basement of the building across the street from our home; I could walk there, as to most places in town. We felt safe in our town, and Chaskel and I were free to walk around as we pleased.

Although I knew my non-Jewish classmates in Polish school, I could not count them among my friends. We sat two to a desk in our classes, but non-Jews never wanted to sit with us. They taunted us, saying that we smelled like onions and, due to our diet, heavily laden with onions, perhaps we did! This could have been general childhood banter, and not something more sinister, but that anti-Semitic sentiment was learned somewhere, and throughout Poland’s history, these attitudes were often taught at home, as well as in church. Aside from such small incidents, I do not recall any outward anti-Semitism intended for my family or me in particular. There were, however, boycott days, when some Poles refused to buy from Jewish stores. I don’t know if my mother’s store was ever targeted before the war, but this may have just been my youthful naïveté, or just the acceptance that this was something that Jews should expect. Jewish students who desired to study in Polish universities were required to stand, rather than to sit at a desk, but this was as it had always been; it was the reality of being a Jew in a country that was no friend of the Jews. Anti-Semitism was standard practice. As Jews, we knew our place in society, so when anti-Semitic acts or taunts increased in small increments, it was not so noticeable.

Every once in a while my family would go to the local movie theater, which played silent and talking pictures. The cinema, as well as our town, was integrated, but there was always a sense of separation between Jews and non-Jews. We recognized Poles from our town, and they recognized us, but any interaction was purely businesslike, not personal.

The Jewish community supported live theater and an array of visiting entertainers who performed in Yiddish. The circus came to Wierzbnik to perform, and I remember seeing a black man for the first time. We were isolated and sheltered in our upbringing and had little experience with the world outside our small town.

Although we were not as religious as some local families, or even as observant as my grandparents, our lives revolved around the Jewish calendar. The rhythm of our lives centered around Shabbat, and other Jewish holidays. In addition to Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, my family celebrated other major holidays, including Pesach (Passover), and Sukkot. The maid helped my mother prepare for Shabbat, buying the meat, fish, candles, and other items for the weekly meal. My mother baked her own challah

and prepared a chopped, sweet fish for Shabbat dinner. We would bathe and wear our finest clothes for Shabbat. Family members living in other towns or cities tended to travel to celebrate major holidays with one another. In preparation for Pesach,

my mother rid the house of chametz,

which included anything leaven. The night before the Seder (the ceremonial dinner when the Hagaddah,

the story of the Hebrews’ liberation from slavery in Egypt, is retold each spring), my father would take a feather and a candle, searching for any last chametz.

If any was found, it would be burned, as was tradition.

“Purim is not a Yom Tov

, and malaria is not a sickness” was one of those expressive Yiddish sayings I often heard in our house and around town. Although Purim is not considered a major holiday, we followed the tradition of shlacha mones

. My mother, sometimes with the help of our maid, would prepare hamantashen,

traditional threepointed cookies filled with prunes, apricots, or other fillings. They would arrange the sweets in a beautiful presentation on china plates that we delivered to family and friends around town.

Although we had a synagogue in town, the Bet Midrash

, people tended to follow a specific rabbi, regardless of where he resided. The Bet Midrash

had a yeshiva

attached to it where “day students” studied Torah. Local families welcomed these students into their homes for meals. Some families with means even gave traveling students a place to spend the night.

Many people prayed and gathered for their holidays in their local shtiebel.

Every shtiebel

had its own Sefer Torah,

a scroll handwritten by a scribe under exacting requirements. The Torah, containing the five books of Moses, is the cornerstone of the Jewish religion and the holiest of its books. The Sefer Torah

was used for prayer services during the week and on Shabbat

. During my youth, the shtiebel

that my family attended was a fair walk from our house, but, during the ghetto period, my grandmother, known throughout the community for her generosity, let the community use a room in her home as a shtiebel.

The spiritual leader who guided some families from our community was Rabbi Yosele of Wochock, from the neighboring city of Radom. Other families followed other rabbis and they worshipped in their own shtiebels

. Before major holidays, my father would travel by train to Radom to seek out special blessings from the rabbi, and to take money to the rabbi for his support.

Although our town was not as sophisticated as Warsaw or other large cities, it was not a primitive shtetl

either. There was a Jewish doctor and a Jewish dentist, and a few other professionals in our town. They were educated elsewhere, as Wierzbnik did not have a university. Dr. Leon Kurta, our dentist, filled my cavities with some kind of cement. Later, we heard rumors that people were having dentists fill their teeth with gold and diamonds as a way of ensuring that they had something of value on their bodies, in case things continued to get worse. Shimon or “

Shimmale,” as he was affectionately known, was our local shoemaker. Growing up, I took my shoes for granted. Only later would I realize the value of a proper pair of shoes, and long for the days when Shimmale would carefully measure our feet and expertly craft our shoes from fine leather. While visiting his shop, Shimon would speak about his devoutly communist views. As time went on, we realized that espousing one’s political views was also becoming more dangerous. Openly opposing the German government, the dictatorship of the Fuhrer, was cause for alarm, and could mean almost certain imprisonment or death. Soon, however, simply being Jewish made one a target of the Nazis and also resulted in imprisonment or death.

To everyone’s surprise, especially to the Poles, the Germans rapidly overpowered the Polish army. In a matter of a few short days, during which we remained in the countryside, the Germans occupied Wierzbnik. Upon our return, we learned that the local school had become German headquarters. We saw ominous Nazi flags flying from government buildings all over town. I gazed upon the German soldiers, marveling at their high black leather boots. It was exciting, but frightening, to see the soldiers in their smart military garb, and to see and hear their trucks and motorcycles in our previously quiet town.

During World War I, my grandfather, Maier, had lived on his farm, a rzepin,

which could be seen from the main road. It had a straw roof and a wood oven for heating. There was a barn with some animals. During the First World War, my grandfather housed a German commandant at the farm and spoke of him kindly and with respect. When the Germans invaded Poland in 1939, my grandfather thought that things would improve for the Jews. Little did he know that these Germans, these Nazis, were radically different from the Germans of the First World War.

German occupation of our town brought fear and insecurity that we had not known previously. The Nazis imposed a curfew of 6:00 p.m. and implemented restrictions on Jews, including prohibiting the use of public transportation. A Jew was required to remove his hat in the presence of German officers. A Jew had to walk in the street, rather than on the sidewalk. And so began the slow torments of humiliation and degradation. Every day brought a new edict, a new restriction on our liberty. At first, these rules seemed rather benign, as they were enacted incrementally. By the time the Jewish community realized we had lost our freedom, our rights, our possessions, and our communities, it was too late.

The Germans established a police force in Wierzbnik. There were the regular police, charged with law enforcement in rural and urban areas, and the Gestapo, or security police, charged with overseeing political crimes.

German anti-Semitism was immediately apparent. We knew that we, not Poland, were the targets of the German war effort. After taking over the town, the Germans imprisoned a number of Jews, who were later freed. Others were consigned to forced labor and made to clear and clean the streets from the destruction caused by the bombing. Poles began shunning their Jewish neighbors and ousting them from bread lines. Food and other supplies became scarce. A few weeks into the German occupation, on the eve of Yom Kippur

, the Germans broke into the synagogue, beat many of the Jews, and forced them into the streets before setting the synagogue ablaze. Like the ancient Temple in Jerusalem, our synagogue lay in ruins.

Just a few weeks after the German invasion, on September 17, 1939, the Soviet Army invaded Poland from the east. Little by little, our country was being overrun from all directions. It became painfully clear to adults that we were not Polish, but Jews that the Poles had permitted to live upon their soil. We were trapped from all sides, with no opportunity to escape. We children were less aware of the political forces surrounding us, but we sensed the increasing restrictions on our once carefree childhoods.

For a short time, the local school was closed, and when it reopened, no Jews were permitted to attend. Jews were forced to turn over their radios, fur coats, jewelry, and other valuables. Even the Poles were forced to turn over their radios and possessions. My brother and I had bicycles, but for unknown reasons, the Germans never confiscated them, as they had in other cities. German soldiers searched the homes of Jews to ensure that the mandates of the Third Reich were followed. Ever so gradually, our rights and movements were taken away.

The mail stopped operating, and the Jewish newspapers were no longer delivered from Warsaw. This, along with the requirement to turn in our radios, led to isolation. Our communication with the outside world came to a halt.

My parents did not make much of turning in the radio. They said, “There are bigger things to worry about.”

They were likely trying to hide their fears from my brother and me, and perhaps it concerned them a little less, as they did not face the humiliation of personally turning over their possessions. My father simply hired a treiger

, a porter, to deliver whatever material possessions were demanded by the Germans. In many ways, during this early period of the war, life went on fairly normally for us.

Our inability to attend school was, of course, a big change in our daily routine. My parents hired a tutor to teach my brother and me. Mostly, we studied Polish with the tutor, who had been relocated from Lodz to Wierzbnik. It must have been difficult to keep two young boys entertained when we could not comprehend the greater situation, and were prohibited not only from attending school but also from engaging in normal childhood activities.

Gradually, the situation in our city, and throughout Poland, worsened. One day, my grandfather, Maier, arrived at home shaken up: “Zayde

, what happened to you?”

He answered with a quivering voice. “I was walking down the street, lost in thought, but aware of the presence of some Germans. The next thing I knew, they grabbed me and held me down. There was a struggle, and when I finally freed myself, I realized they had cut half of my beard.”

“What will you do now, zayde

? Will you shave the other side?”

“No, my dear boy, I am a religious man. I will cover my face with a handkerchief until it grows back.”

This aggressive act by the Germans, on a public street, was meant to intimidate and caused my grandfather great embarrassment. We felt his shame, but were grateful that nothing worse had happened to him. We were beginning to learn to what extent the Germans would go in punishing Jews. On one occasion, four people from our town were taken away. Caskets containing ashes (presumably of the four) returned. People were in shock, asking what kind of civilized people would do such a thing

? We were beginning to learn what kind of people could do such things: everyday people easily led by the Nazi machine, people who conformed in order to protect themselves, or to get ahead. The Germans’ random acts of violence horrified the Jews of Wierzbnik who, like so many other Polish Jews, were hardworking, God-fearing, peace-loving people.

Before the war, Wierzbnik had some four thousand non-Jews, and eight hundred Jewish families. At the start of the war, the Jewish population had risen to roughly three thousand six hundred Jews, and fluctuated throughout the war based upon various transports from other shtetls

and towns. Trains carrying Jews from Lodz arrived in Wierzbnik on March 2, 1940 and March 13, 1940; another train carrying Jews arrived from Plock in March 1941.

On November 23, 1939, a Judenrat

was established, along with a fifteen-member Jewish police force charged with keeping order within the Jewish community. The Judenrat

(or Gminna

, as it was called in Polish and Yiddish) consisted of members of the previous community council, headed by Symcha Mintzberg and Moishe Birencweig. The Germans required the Judenrat

to raise one hundred thousand zloty

and to provide approximately three to four hundred able-bodied men for forced labor for the Third Reich. These laborers were sent to work in surrounding villages. My father managed to avoid these forced labor assignments, probably because of his connections or contributions to the Judenrat

.

In early 1940, the Nazis ordered all adult Jews to wear a white armband with a blue Star of David or the word “Jude”

on it. When this law was enacted, people felt the pain of degradation. The armband, which Jews had to make themselves, was to be worn at all times when outside one’s home. I was too young to have to wear one, but I remember that adult Jews wore them until deportations to the concentration camps began.

Amidst the tumult and uncertainty, life continued: people married, babies were born, other life-cycle events occurred, and I turned ten.