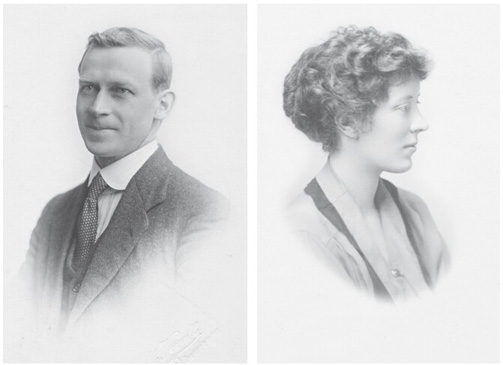

Theodosia Jessup met the Methodist chaplain and English writer Captain Edward J. Thompson in the summer of 1918 in Jerusalem, where he was on leave and she was helping run the Mount Sion orphanage, teaching Arabic and French. The writer Margaret Storm Jameson recorded: ‘[Edward] married the one woman he should have married, an American, the serenely beautiful child of American missionaries in Syria.’ She was known for having hair of so golden a colour that ‘you could lose a sovereign in it’, for having numerous admirers, and for having extricated a donkey from a ditch, stubbornly pulling it by the tail. She had courage, intelligence and will power. He, at thirty-three, was seven years her senior.

Edward’s courtship of Theo lasted six troubled weeks. She approximated to the ideal type he most admired: a graceful upper-class blonde seated on a horse. She had been educated at a patrician college in the US and was a skilled linguist, while his education had been hit-and-miss. It is likely that she mixed with grander people in Jerusalem than he did. While he had taught himself to enjoy riding, she had ridden well from childhood.

But there were difficulties involving friends and one past lover. She sometimes found him conceited; he thought her censorious. Not for nothing were they both children of missionaries, this chapter’s topic. She disliked seeing him drink and he had to explain that he had never smoked till he was thirty, and nor had he during six long years in India adopted the habit of the chota peg. Only after his wartime breakdown when many friends and a beloved brother had been killed had his habit of a single evening ‘sun-downer’ started. Watching so many innocent men die in agony had left him drained, disillusioned and doubting God’s goodness. Though her alertness to sin and ugliness sometimes made her ‘a silly goose’, he also told her that her poise, ‘queenly self-control’ and ‘daintiness’ (by which he meant fastidiousness) might in time redeem him. When she agreed to marry, he wrote, ‘No English poet before me, save Browning, has been so lucky.’ This flattered them both, implying that Theo had a poet’s mind, too, worth weaning from harshness. Her love is not only to help him to fame – for which he pretends to care nothing – or peace of mind – which mattered ‘a great deal’ – but to help him back to God. He felt a misfit among the tribe of ‘narrow, savagely self-righteous men’ from which he came.

As for Theo, she married a penniless Methodist minister against the wishes of worldly-wise friends, some of whom – who knew the foolish English social discrimination against non-conformists – were angry and horrified. Others declared themselves very sorry for her and disappointed that life should have closed down so suddenly. But she was attracted by the fact that he was a published writer, with two plays and five books of poetry to his name.3 He sent her copies. Somehow they understood one another.

They married on 10 March 1919 in the classic and magnificent great inner court – Da’ar in Arabic – of the aristocratic Beirut house rented by Theo’s missionary father William Jessup. Before the war the Jessup family believed James Elroy Flecker, an inefficient British vice-consul, had stayed there, writing The Golden Road to Samarkand with its perfumed Orientalism and being visited by an admiring T. E. Lawrence before starting to succumb in April 1913 to TB. The villa’s palatial rooms stayed cool through the intense heat of summer.

This hall, sixty feet long and proportionately wide and high, featured many doors leading off into stone-built state-rooms, fine rugs cast over the black-and-white marble floor, and clerestory archways at each end to receive light, with panelled screens of intricately carved wood standing beneath. Edward’s fellow officers of the 2nd Royal Leicestershires attended in full dress, and Edward wore the Military Cross he had been awarded for bravery in Mesopotamia. The palest apple-green taffeta gown a friend had sent for Theo she gave instead to her sister Faith, her only bridesmaid.

There was much to celebrate. The Great War, during which 10,000 had died locally of famine, had recently ended; the British Army had entered Jerusalem, overturning four centuries of Turkish rule, and were heroes of the hour. Ottoman suzerainty had been hard for Protestant missionary families like the Jessups. Perhaps the coming of the British heralded a brighter future? Edward was their triumphal representative. He was witty, ambitious, impatient and capable of heavy irony; she was less worldly than she appeared. When he joked about the limitations of the country he always waggishly called ‘Amurka’, she was not amused.

Theo’s grandfather Henry Harris Jessup arrived in Beirut, after a wretchedly stormy voyage, on the sunny spring morning of 7 February 1856. He had sailed on a slow 300-ton bark – the Sultana – laden with a mixed cargo of New England rum-kegs destined for Smyrna and carrying eight teetotal Presbyterian missionaries who intensely disapproved of alcohol. They had embarked during a freezing Boston snowstorm, arriving weeks later into an early spring landscape of flowers and white almond blossom. The custom each anniversary of exchanging almond sprays as a thanksgiving offering was shared for decades by this closely interlinked American group, who resembled a large extended family.

Beirut then numbered 8,000 souls, and a church meeting convened on the day of arrival included a richly gifted Lebanese, the founding father of Arab nationalism, Boutros al-Boustani, whose family had been Maronite, a sect allied to Catholicism. Maronites and Greek Orthodox, hostile to these Americans, anathematised those of their flock who became Protestant. Al-Boustani had a price on his head: the Maronite Patriarch had already had another Presbyterian convert killed.

Eastern Christians had grounds for hostility. The Ottomans had declared the conversion of Muslims illegal; one such convert had also been killed and others smuggled out of the country. When Jessup against the odds converted a single Muslim, the book he published about it was grandiosely entitled The Setting of the Crescent and the Rising of the Cross (1899). His sole convert – Kamil Ataini – died in suspicious circumstances in Basrah. Jessup longed for British rule in the hope that it would sanction the conversion of Muslims. Meanwhile the different Christian sects poached each other’s adherents.

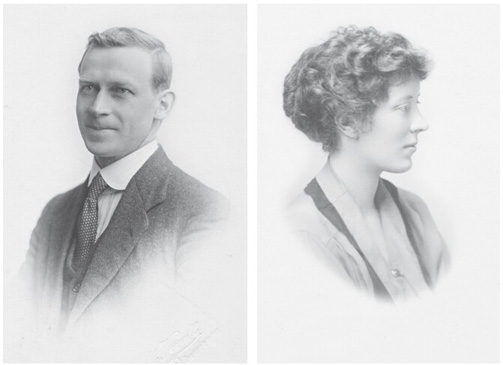

Henry Harris Jessup, the grandfather whom Theo knew well – when he died, a white-bearded figure in a frock coat, she was eighteen – is by any standards extraordinary. After graduating from Yale he lived for fifty-three years as a missionary in Syria – the name until 1920 of the territory encompassing both the Lebanon and present-day Syria. Here he taught himself Arabic well enough to preach and even to publish a book of children’s verse. He was a learned man – what the eighteenth century called a man of parts – with a breadth of knowledge from the classics to geology and world history that in Europe goes with tolerance. He knew his Gibbon and Voltaire – but if not a bigot he was certainly a religious zealot.

His many well-written books showcase his Syrian work, inveighing equally against Islam and non-Protestant Christians, whom he labelled ‘Nominal Christians’ only. Greek priests are rich, greedy, unscrupulous, ignorant and corrupt vagabonds adhering to false and superstitious doctrines, selling Absolution, idol-worshipping the Madonna and Saints, practising confession and offering Prayers for the Dead. Instruction in the Scriptures is virtually unknown: when the Americans distributed Bibles in Arabic, Greeks and Maronites collected and burned them. They have so many holy days they keep none, being too busy propagating ‘a bitter feeling of [sectarian] party spirit’, a phrase whose sheer double-think takes away the breath. He evidently held the Calvinist belief that he belonged to ‘an Elected Few’.

Jessup estimates the number of Eastern Christians worldwide in 1910 at ten million, but he believes that God will help all these discover ‘gospel light and liberty’, after which all Islam will follow, because in the day-to-day piety of Jessup and his like they will actually see ‘the Bible acted out in Life’. Statistics were massaged: a published 1882 statement claimed 3,894 Presbyterian Syrian converts, while an unpublished letter admitted only 1,542.

His books paint a picture of a Syria designed to alarm and to excite generosity – fallen from erstwhile greatness, plagued now by locusts and lies. A few examples will suffice. The local custom of rapidly interring the recently dead ran the risk that terrified Edgar Allan Poe: awakening to discover that you are buried alive. Then he claims a local doctor gave as one quack remedy, pulped into a liquid, some pages from the New York Tribune (‘Do tell me how it acted?’ its editor asked Jessup. ‘Cathartic or Emetic?’). Here was a land in need of modern medical knowledge.

The treatment of women inspired him to write The Women of the Arabs (1873). The burial alive of female babies was an ancient tradition, and in 1857 the wife of one American missionary endured being routinely spat at. Muslims still condoled with each other when a daughter was born, names for girls including Just Right and This Is Enough. Arab women were subservient, forbidden to pray in mosques within sight of men, their state ‘vile and degraded’. Traduced as greedy, unclean cowards, they cannot inherit and so live as a chattel of their husbands, who can divorce them at whim. Women are poisoned, thrown down wells, beaten to death and drowned at sea. The Qur’an promises a good Muslim in Paradise seventy-two houris or heavenly concubines, on top of his statutory four wives. Jessup hints at practices too barbarous to name.

Jessup’s championship of the welfare of women was qualified in the case of his eldest child Anna, manipulated into staying at home after she had fallen in love. Jessup and his wife ‘interposed’ with ‘various and sundry reasons’. Their trump card was to terrify her with her ‘inherited predisposition to puerperal fever’, to which they were mysteriously privy. In his magnum opus Fifty-Three Years in Syria, he accordingly thanks Anna for her ‘invaluable aid’. Like other Victorian women Anna evidently became a cheap housekeeper, amanuensis and drudge.

Jessup tells one tale so obscene it recalls Fox’s propagandistic Book of Martyrs. An Arab mother maddened by grief at the death of her son was taken to a quack Muslim ‘Saint’ for a cure. This Saint, in order – as he later claimed – to cast out her devils, hung her upside-down, used a red hot poker to jab out one eye, and then, setting fire to a gallon of pitch-tar, burned her alive. He was not brought to trial. One can imagine how this tale might help fund-raise for a mission presented as sole bulwark against such horrors.

Poisoning was one traditional way of settling disputes. Jessup proposed an antidote. His fellow missionary Dr Daniel Bliss in the 1860s founded the Syrian Protestant College to correct such barbarities. Its pathological laboratory tests identified poisons, bringing culprits to justice. It was renamed after 1920, to attract a larger constituency, the American University of Beirut (AUB).

The AUB also incorporated from its early days a seminary for wealthy young ladies. Jessup’s claim that his was the sole mission teaching Syrian women reading and writing, nursing, domestic economy, cooking, sewing, geography, history and arithmetic would also have rallied support. In reality Catholics – especially the French – soon outdid them. During the 1870s Maronites and Catholics replaced the Orthodox as the Americans’ chief rivals. Small surprise Jessup soon recorded that Papal beliefs were ‘semi-barbaric’, or that Theo later remembered Catholic priests in Zahle encouraging children to throw stones at the Jessup family.

The names of Jessup, Dodge, Leavitt and Bliss, all associated with the AUB, have been well known in the Lebanon now for a century and a half. E. P. Thompson, great-grandchild of Henry Harris Jessup, was informally sounded out after he graduated in 1946 for a post at the American college but made it clear that he was politically incorrect for such a position. The AUB was then starting to be seen by EP’s mother Theo as an instrument of the State Department if not of the CIA. The family connection none the less persists. As recently as 1997 AUB founder Daniel Bliss’s great-grandson David Stuart Dodge (1923–2009) was AUB head, despite having being kidnapped in 1982 for a year by Shi’ite Muslims. The current President (2009) is another descendant.

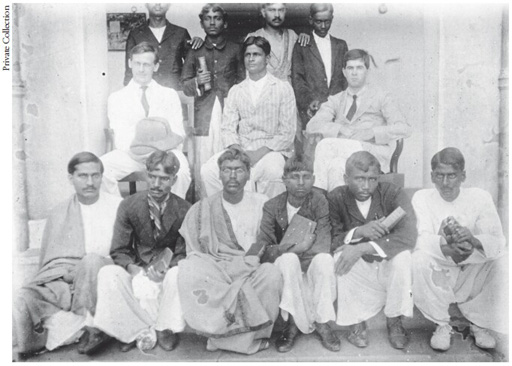

The American Presbyterian Community in Beirut, c. 1890. H. H. Jessup is seated centre, with stick.

These families, moreover, were related by kinship as well as denomination. After giving birth to three children Jessup’s wife fell ill and died in Alexandria. Jessup remarried in 1869 Harriet Elizabeth Dodge, with whom he had five children before she too died in 1882. The 1890s in Syria have been called the ‘age of the Jessups’. Henry was surrounded by numerous close and distant relatives in mission and college: ‘discipline was tightened, conformity expected’. His eldest son William, another missionary, arrived from the USA in November 1890, with his new bride Faith Jadwin, whose family money came from patent medicines, as reinforcements. Henry advised William always to travel both with his own cook and with clean bedding, thus avoiding the risks of food poisoning, fleas, lice and bedbugs. William would ride out for a fortnight at a time into the plains of the Beka’a valley on Gypsy, his fine Arab mare.

Theo, eldest of William and Faith’s five daughters,4 was born fifteen months later. She was named after Henry Jessup’s third wife, her step-grandmother Theodosia; it was a name she always disliked.

Arab culture, language and traditions were despised and languished under 400 years of Turkish rule. Lebanese Christians played a well-attested role in agitating for independence; and the founding of the AUB – followed by an American Hospital and schools – remains the missionaries’ main public achievement, helping a native and ecumenical Arab nationalism to blossom. In this they were more successful than the missions of other countries. The AUB’s language of instruction in 1866 was Arabic, which helped raise confidence, and thus the AUB set in train a revival of the Arabic language and literature and with it ‘a movement of ideas which was to leap from literature to politics’.

Theo’s youngest sister Jo towards the end of her life wondered whether the Jessup influence on the Lebanon had been futile or even pernicious. This judgement seems harsh: the admirable paradox both about the Jessups in Syria and about Edward Thompson in India is that, arriving as apologists for Western culture, they stay on as champions of local customs and history, turning into anti-imperialists whose most devout wish is the political independence of those they once wished to dominate (India) or convert (Syria). To differing degrees both Edward and the Jessups, in the slang of the age, ‘went native’.

Such an anti-imperialist legacy is all the more commendable in that vulgar racism hurt early Jessup efforts. An American citizen applying for missionary employment in 1854 was rejected because he was not of WASP descent but Armenian; while the great Boutros al-Boustani, then helping to translate the Bible into Arabic, was turned down for ordination in 1857, redirecting his huge energies thereafter into education, producing the first Arab-language encyclopaedia and dictionary, and starting up newspapers and a review. Though they came to establish a native Church, the pastorate of the first native Protestant Church in Syria forty years after its establishment continued to be held by Jessup, an American. Were mission funds, he demanded to be told, ‘really to be at the disposal of irresponsible natives’? The mission indeed paid Syrian teachers $30 per month when American teachers claimed over $200 a month themselves.

The missionaries early established for themselves a tradition of spacious houses with servants and carriages, the Jessups decamping with their possessions by mule-train in summer from a beautiful house at Zahle in the mountains to another at Aleih high above Beirut. Henry Harris Jessup rebutted the charge that they were living in luxury.

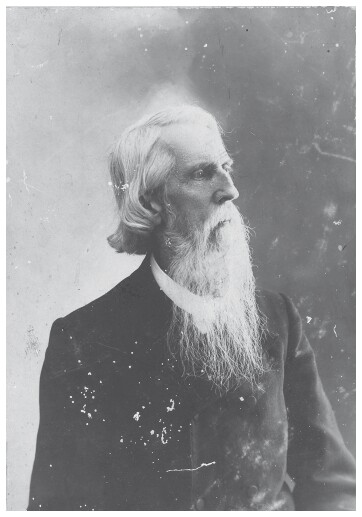

Here in the biggest house in Zahle Theo and her four sisters were born and brought up, living with a second missionary family, stockaded all together, as it were, in an American frontier settlement. The Jabal Sannin, second highest peak of the Mount Lebanon range at nearly 9,000 feet, gives Zahle its fine stream, the Bardouni, one reason for its popularity: it brings down with it the cool air enjoyed by townsfolk eating mezze in the outdoor cafés or on their terraces, shaded by vines growing up trellises, and by mulberry trees for cultivating silkworm. The town’s hard-working inhabitants brokered the sale of Bedouin sheep to Beirut, Egypt and Palestine.

William, ‘very formal when he talked to God’, took morning and evening prayers, reading from the New Testament in Arabic so the servants could follow. His wife and daughters learned Arabic too and loved the Lebanon: it was ‘a pioneer . . . close-to-the-country’ way of growing up. Their mother Faith, a good seamstress, made clothes for her daughters on her novel American sewing machine; though the family did not much mix with natives, a lady from the prominent Shehadi family helped, squatting cross-legged on the floor.

During a typhoid outbreak in 1897 Faith gave birth to a boy, another Henry. Before long her husband, William, recovering from a forty-day delirium, learned that this baby son, suffering from Cholerum infantum, had died and was already buried. Although they were finally nursed back to health, his wife and daughter Beth sickened too. The family fought successfully thereafter for a good water supply by getting a reservoir constructed.

Not only Syrians ardently desired boys: Faith took the loss of her only son very hard. Her fourth daughter was born in 1902 – a year when, ominously, and despite the help of an American nurse, Faith’s sister Amy died in childbirth. Although Faith was warned that another baby might kill her, she persisted in hopes of a son, suffering many miscarriages. By 1911 she was pregnant once again, and Theo was summoned home after her sophomore year at Vassar College in upstate New York on fictitious grounds of her mother’s ‘kidney trouble’. She returned instead to find her mother, while giving birth to her youngest sister Marie-Josephine (aka Jo), on her deathbed. Arab women walked shoeless over the mountains to attend her funeral, and much later, in 1965, a school named after her opened in Zahle.

The exaggerated sense of responsibility an eldest child sometimes manifests had rational causes in her case: the nineteen-year-old Theo interrupted her studies to come back and care for four half-orphaned sisters and a grieving father during two hard years of loss and mourning. Theo’s surviving diary makes clear her piety and her protective anxiety about her baby sisters.

In 1913 the addition to the household of a demanding, old-maid-like stepmother called Kate ended this episode. Later, going through her father’s papers, Theo saw that marriage to Mother Kate brought much-needed money into the family. And Theo felt displaced by Kate – otherwise she could have been the centre of the family and have brought up her sisters herself. Kate, among other sins, burned their mother’s diaries. Theo duly returned that year to Vassar, where she was twice president of her class.

Theo’s sister Faith once compared American young ladies’ over-protectedness with that of Arab women. Even after the Great War the girls accounted themselves, in a happy phrase, ‘harboured with rectitudes’, inhibitions as much provincial as religious. They enjoyed card games, albeit never in front of Syrians, and eschewing court cards. And when the sisters danced the polka at home, it was not the indecency of the dance that affronted their father William but the fact that some of his daughters had donned men’s trousers. The girls noted drily that this was how Arab women dressed most of the time.

Of the Jessups Theo once recorded accurately that ‘Ten branches (at least) of the family emigrated from England to America in the seventeenth century.’ That ‘at least’ is both studiously vague yet boastful: the Jessups are an East Coast establishment family, Henry Harris’s father having chaired Abraham Lincoln’s nominating committee. Five of Theo’s Jessup first cousins, all boys, were rich power-brokers. The middle child, Phil Jessup, who married Lois Kellogg, would be US representative to the UN under Harry Truman and later John Kennedy’s candidate for the International Court of Justice. Their family’s extensive property had been in the family ‘about 300 years’. On the Jadwin side (Theo’s mother’s family) one aunt in 1964 left to Princeton what at the time was the biggest single bequest ever made – $27 million. When common people began to move into the part of Brooklyn Heights where two Jadwin widows lived they simply bought the surrounding houses and pulled them down. Theo’s was a cadet branch, so that, though she had some money, there were always rich relatives on both sides to whom she and her sisters felt they should behave obligingly.

Kindness, courtesy and closeness to God, Theo later maintained, were Lebanese characteristics. High-minded and public-spirited families such as hers are much to be admired. Fadlo Hourani, father of the historian Albert Hourani, converted by Daniel Bliss, was impressed not by his Calvinist belief in predestination so much as by the admirable life-example these Americans set: sobriety in dress and conduct, avoidance of extravagance and ostentation, help to one’s fellow man and good works. Such qualities Theo brought to her marriage, and – soon – to her two sons.

Art and music were ‘all around’ the Jessup girls as they grew up. Theo and three of her sisters wrote plays; one of their Beirut aunts ran a choral society; other aunts – and sister Beth too – painted. They had – so long as these activities were carried out in private, and not in front of Syrians – real scope and freedom.

Edward came into a very different inheritance. As a very little boy at a local pre-prep school he won a box of watercolours as a school prize. He brought them delightedly home where his father, the Rev. John Moses Thompson – in outrage and disgust – threw them on the fire. Born near Stockport (Hazel Grove) in 1886, he was the second of six children, four boys, two girls,5 of a Wesleyan minister who took his family when Edward was one year old to live in Tamil Nadu, South India. Edward survived typhoid there; his father’s pleurisy was more serious, necessitating their return in March 1892. In September that year they moved to live in the Manse at Colwyn Bay where the acute 1893 flu epidemic permanently weakened his mother’s heart and triggered his father’s final decline: on 7 April 1894, two days before Edward’s eighth birthday, he died, leaving his widow in desperate straits. She had a family of seven with an annual income of £100 to try to subsist on.

EJ in 1902, aged sixteen.

In 1897 Edward was sent to Kingswood School in Bath, open to the sons of Methodist ministers, which had been founded in 1748 by John Wesley himself. It was in the process of ‘normalising’ itself as an independent school, turning away from narrowness and joylessness, incorporating rugby football and a house system, and, in 1902, employing as English master Frank Richards,6 who fed and encouraged Edward’s intense and passionate love of literature. Edward won literary prizes, yet lampooned the school in one novel as a place of licensed bullying, flogging, a style of teaching given to catechism, and hated rice puddings. Edward’s closest Kingswood friend George Lowther told him that his bitterness was baseless if not ‘absurd’.

Edward’s grievance was enhanced by the fact that, also in 1902 when he was just sixteen, with reasonable hopes of an Oxbridge scholarship, his beloved mother asked him to come home to support the family financially: they lacked food. He accordingly worked as a clerk in the Bethnal Green branch of Midland Bank in the East End of London where he earned – after five years and including overtime – only £80 per year. Work with the Boys’ Brigade, a Christian organisation, Sunday school teaching and outdoor preaching (leading to sciatica) filled some leisure hours; he won occasional half-guinea prizes for his verses in Westminster Gazette competitions and often spent his lunch money of seven pence (worth a few pounds in today’s money) on books. This recalled Dickens’s nightmare childhood interlude in the shoe-blacking factory: here his hopes for self-improvement were thwarted.

His family fed this life-myth. One year after Edward finally escaped from the bank to train as a minister himself at Richmond Theological College, where he gained an external London University BA, his youngest brother Frank, aged fifteen, was summoned from Kingswood to work very long hours for the family with the publisher J. M. Dent, then starting the Everyman Library in Letchworth in Hertfordshire. Frank’s health also suffered and he too hoped to attend evening classes to qualify for a better job. Yet it was Edward’s sacrifice, not Frank’s, that was remembered. Frank’s nickname for Edward – ‘big boy’ – attests to his all-important seniority, and his sister Margaret wrote, ‘we all owe a tremendous portion of our happiness to you’. Edward’s sacrifice was, by implication, the significant one. His bank years from 1902 to 1907 amounted to a standing deficit.

EJ standing behind his mother, flanked by sisters Anne-Margaret and Mollie, and by brothers Alfred, Frank and Arthur.

Not that Edward’s hardship should be under-played. These five years resembled an iron band around a growing tree: he suffered real poverty, grinding work, insufficient food and exercise, no holidays, and a dearth of friends. He watched Kingswood contemporaries’ careers overtake his own and started a spiritual/psychological agon that would not end till 1923 – a conflict between piety and poetry. Methodists regarded the arts with vigilant suspicion, and Edward believed his twin vocations – pastor and poet – to be in contradiction. The most important problem of his life was reconciling his passion for poetry with his religious urgings.

In 1904 he and Lowther were oppressed by a fear that the pleasure they took in poetry (reading and writing alike) might be sinful. Edward’s ‘wrestling Jacob’ experience lasted for months, and encouraged his growing conviction that he should give up writing poetry. This passed, but not without a shadow. In 1907 he funded publication of Knight Mystic – Verses from a small inheritance and put up with misunderstanding, rude questions and cheap wit from fellow ordinands. His mother was sixty before she entered a theatre, finding much in Shakespeare to offend, while Edward was twenty-four when he saw his first professional Shakespeare – The Taming of the Shrew in 1910. Lowther, who believed in Edward’s gift, paid most of the cost of the private printing of his mock-Elizabethan hotch-potch play The Enchanted Lady. The same year a group of Wesleyan ministers in Gloucestershire challenged ‘the propriety of his writing poems of a personal nature’.

In October 1910 he was ordained minister, accepting a posting as a missionary teacher to Bankura School and College in Bengal. His motives included the desire to escape constriction, the hope of pleasing his mother and the prospect of teaching English literature. He also had happy childhood memories of long, slow South Indian afternoons with little green parrots flying from the tops of enormous trees, of palm-fringed beaches and of community life within the compound enveloping a child in warmth and security. He had been fluent in Tamil. He sailed on 21 November from Liverpool, on a four-week voyage to Madras.

Bankura was different. Edward arrived with no knowledge of the Bengali language or of Bengali history in a landscape he found monotonous. Bengal was politically restless after its recent clumsy partitioning, which was due to be annulled in 1911 after six years. During the durbar held at the end of that year to mark the coronation of George V, the capital of India was moved from Calcutta to New Delhi, causing further antagonism among Indians. The Swadeshi (‘Own Country’) movement urged the boycotting or burning of European goods, especially Manchester cloth.

The pupils put up good-humouredly with scripture lessons to acquire enough English for university entrance and white-collar employment. As with the Jessups in Syria, it was the missionaries’ provision of education here that was precious and life-changing – not their evangelism. Indeed when the first local boy for ten years converted to Christianity, Edward thought him a fool. Edward quickly gained a reputation as a gifted teacher of literature, launching at least one student on a distinguished scholarly career, publishing an Anthology of Verse for Indian Schools (1915) and a Handbook of English Prosody and Poetry-Writing for Indian Students (1924). He also liked teaching football and cricket, excelling at both.

Yet, for all his receptiveness to the charm and the comedy of Indian life, Edward felt ‘absolutely alone’. Indians lived behind their own intrinsic colour bar; English Wesleyans offered little by way of companionship or intellectual challenge. In 1912 publication of his John in Prison, a collection of poems, led to a stupid, upsetting attack from a fellow missionary who appreciated Edward’s ebullience but resented his conceit. Self-pity and an ineffectual attempt to move to South India followed. The real, consequential move he would make was a lateral one, into Bengali culture, which soon refreshed his spirits: by 1913 he was a fluent Bengali-speaker and starting to acquire a better knowledge of Bengali poetry than that of any other Englishman.

Edward, who had lost his father when he was seven and collected older literary mentors, travelled that autumn for a momentous meeting with the patrician Rabindranath Tagore, whom he believed the world’s greatest living poet. Tagore spoke of the loss of his wife, son and daughter, Edward of Lowther’s recent death by drowning in the Lakes. Edward’s great gift was for empathy and friendship, and he recorded after meeting Tagore that he now felt more at home than ever before in India.

The sudden fame in the West of Tagore (1861–1941) – educator, poet, playwright and novelist – resulted from relentless campaigning by W. B. Yeats, Ezra Pound and William Rothenstein. During Tagore’s recent, triumphal stay in London, they introduced him to the ‘right’ salons, magazines and patrons. Yeats’s preface to Tagore’s Gitanjali, lyrical prose-poems in praise of God, publicised the ‘mystic’ who, Yeats claimed, was famous throughout India. Tagore was in fact scarcely known outside Bengal.

Yeats also underplayed the fieriness of Tagore, whose essays, lectures and patriotic songs antagonised the British, whose best stories celebrated the lives of the poor, and who would firmly renounce his English knighthood after the 1919 Amritsar Massacre. The second time that Edward met Tagore, a sheaf of telegrams interrupted supper, announcing that he had won the Nobel Prize for Literature: the first Indian ever to do so. Sadly he remarked, ‘I shall have no peace now, Mr Thompson.’

Edward’s own conversion-experience had begun. He had started that night on the path that would lead eventually to Mahatma Gandhi calling him ‘India’s prisoner’. Among the fifty or so books he would write are two controversial studies of Tagore, novels set in India and notable histories of India, and he would spend over twenty years as lecturer in Bengali and Sanskrit at Oriel College, Oxford. Albeit not the bardic role he most desired, Edward would, through his vexed friendship with Tagore, find a vocation: as go-between or ‘Friend of India’ to the Indian press, explaining one culture to the other, an Alistair Cooke to the sub-continent. His younger son would eloquently call him ‘a courier between cultures who wore the authorized livery of neither’, an outsider wherever he went. This task, in the long run-up to Indian independence, was fraught with misunderstandings. With one exception, his books today in the United Kingdom are out of print and forgotten; in India interest in him, and in his publications, continues.

EJ (second row, seated left ) with staff colleagues at Bankura, Wesleyan College, c. 1915.

Edward served with distinction as chaplain in Mesopotamia and Palestine in 1916–18, an experience retold in three of his books, most memorably in The Leicestershires Beyond Baghdad (1919) which was reprinted in 2007. That Indians in Mesopotamia outnumbered British soldiers three to one, fighting bravely for an empire not of their own making, helped Edward further to sympathise with them; their generosity and gallantry touched him deeply.

EJ in 1918.

One incidental annoyance of the Mesopotamian theatre of war was that, compared with Flanders, it was seen as a tiny sideshow in the Great War, concerned more with oil than with territory. Edward’s list of the many other miserable small vexations is long and impressive: bad water from filthy wells that sickened you, blinding dust-storms that made your papers fly twenty feet into the air and had you fighting for breath, and could even cause your rifle to fall and hit you on the head as you lay in your tent. In certain seasons the dreadful heat, thirst and flies of the day combined with penetrating cold at night to conduce to a sense of ‘insane wretchedness’. There were grass needles, sandflies, mosquitoes, large black biting ants, snakes and scorpions; long footsore marches and the uncertainty for months at a time of mail getting through; and then also colitis and rheumatism and unspecified ‘old troubles’. When Edward’s physical and psychological health finally gave up he was sent back to India for a month to recover.

Great resentment was caused by Bedouin Arabs surreptitiously digging up the British dead to plunder their graves. Edward, reflecting on how sacrosanct graves are in Islam, sees that such tomb-robbers are, according to their own ethos, criminals. This scavenging of the dead – like the cruel murder of isolated wounded Britons for purposes of loot – causes burgeoning anger. Maddened by repeated desecrations, a British Tommy carefully digs dummy graves and mines them with Mills bombs (hand-grenades) whose pins he removes, employing a precarious weight of soil to prevent their immediate detonation. He and his friends then sit quietly by and watch with satisfaction the grave-thieves approach and duly dig with their fingers, before the booby traps find them Elijah’s way to heaven ‘fiery chariot-wise’. To these desperate people, Edward comments, even life and limb were worth risking for some small gain; their callousness, he notes, stems from hopeless poverty.

He has an ear for comedy, japes and practical jokes: camaraderie consoles him. Nature too: fresh fruit in season – mulberry, pomegranate, fig and date. He was already a gifted nature-writer whose spirits could be lifted by bird-life – crested lark, owl, sand grouse, stork feeding on grasshopper, a hawk or two and brilliantly plumaged roller, bee-eater and kingfisher.

Edward dedicated this regimental history to his brother Frank, an idealist who sang in the Alexandra Palace choral society and joined the Independent Labour Party. Frank felt unhappy about the war’s aims, but the first Zeppelin raid over London in May 1915, ‘the sight of an evil he had not imagined’ – the bombing of defenceless women and children – drove him to enlist. He served the average for a second lieutenant in the Flanders trenches in the bitter winter of 1916/17, three months, before being shot and killed by a sniper’s bullet on 15 January 1917. His fiancée had just lost her brother. Frank is buried at Ypres. Like his nephew, another Frank and another idealist, he was remembered as gay, selfless, courageous, beloved. Edward told Theo that, night after night for many months, Frank’s image crowded in upon his thoughts. He would return to Frank’s death on the final page of These Men, thy Friends, his 1927 novel inveighing against the unparalleled stupidity and incompetence of English generals and press hangers-on in Mesopotamia, while celebrating the quiet patience especially of Indian soldiers. Chaplain Kenrick is Edward, whose brother Frank appears as John. When Edward left England in 1910 Frank was barely seventeen: on the last pages Kenrick/Edward reflects that he never saw the man John/Frank became, and had to intuit his newfound ‘strength and poise’ via his letters. The family at home had learned to lean upon his courage and gallant cheerfulness, and to one sister he was ‘inexpressibly dear’ – a phrase Edward would unconsciously recycle for his own elder son in 1944.

The painful fact is that Edward, longing above all else to write one great poem, mistook his own gift. He was an old-fashioned, observant nature-poet who went in for intense mystic questioning within a dissenting Christian tradition. But – and although his later poems are stronger – it is as a prose-writer that he excels. His account of the random obscenity and terror of modern warfare survives his own prettifications. He recounts in horrifying detail his attempt to save a Turkish sniper who is still alive despite his brains running down his face. Edward’s attempts to lift this heavy man simply result in his staining his clothes red with blood. Later, this man has dug a hole in the thorns to bury his piteously tortured face, his legs waving feebly like an insect’s, and by the following morning he has crawled some hundred yards before dying. Edward recorded the death of another man, ‘invertebrate . . . like an eel’, and calling out in his agony. Edward once shared an oil-sheet with a corpse.

Helping the doctors and purveying accurate news are jobs for chaplains. While Edward boasts of his own insouciance, he never mentions that he was awarded the MC for bravery – taking two Turks prisoner, nursing the wounded (the fighting at Istabulat and Samara, though it cost 2,400 casualties, earned only a single line in a Reuters report). He regards the Turks as worthy adversaries, brave and carrying themselves like free men, loyal to one another: ‘Johnny Turk’ was a term of affectionate regard. He bandaged and rescued Turks as well as Britons.

Theo’s college friend Melanie Avery, Theo and EJ at Buckingham Palace for his investiture with the Military Cross, 1919.

You sense the author bravely trying to gain a perspective in all of this, on what was inexpressibly horrible. He does not always convince. He claims that Henry V’s great speech before Agincourt was quoted by the Leicestershires three times. Henry famously glories in an unequal fight – ‘We few, we happy few, we band of brothers’ – but by Edward’s third citation you tire of this bravura and (even if true) find it literary and improbable. Edward parades other antique sources – Xenophon, Virgil – to dignify and console; it was a cultured habit of mind his sons inherited. He shows off his learning: ‘maniple’, ‘meinie’ and the Shakespearian ‘maugre’ are not common words.

Yet truth has a way of breaking through. A curiously prophetic episode entails a press movie-photographer choreographing war scenes with an eye to cinema audiences. He asks an ambulance crew to remove from their vehicle a wounded Turk whose stretcher they have just loaded, and then to drive up smartly once more towards the camera, before again reloading this poor casualty a little faster. We have grown used to the cynical press-manipulation of image into factoid; this same photographer later stage-manages a shot of a gruesome dead Turk with Edward and a doctor standing behind. Here are striking early instances of pseudo-events or war as mass entertainment.

An unnamed witness in June 1919, watching the newly married Edward climbing a hill through young corn near Jerusalem, noted how carefully he moved – as if he feared damaging the crop – and commented astutely, ‘I rather suspect that thoughtfulness is typical of him.’ Like so many who survived the slaughter of the Great War, the experience marked him for life. Thoughtfulness was one result, rage against a world order that caused the disaster was another. And fear of the future.

EJ by the Wailing Wall, Jerusalem, summer 1918.

Like his wife Theo, Edward inherited from his missionary background an alarming high-mindedness and idealism. There were related habits of priggishness and an exaggerated sense of responsibility. These qualities – together with an impassioned anti-imperialism and internationalism – they duly passed on to their two sons, both of whom Storm Jameson described as ‘intransigent idealists’. Each – differently – showed prophetic zeal and purpose, albeit in a secular and political fashion. The Great War also inspired in EJ a theory that Britain’s guilty imperial past required a cleansing sacrifice or atonement – and Atonement was the title of a play about India he wrote in 1924, revived during the Second World War. He could not know how literal-mindedly his elder son would listen to and act this thesis out.