A Desultory Tale: January–September 1943

Death should not be allowed . . . more of a victory than is its due . . . or allowed to corrupt life with its sterility.

Letter, 3 May 1943

When I think I have reconciled myself to the idea of dying, is this merely the death-wish, a defeatist attitude to the complexities of life? Don’t think so. Normally I take a healthy pleasure in living . . .

Diary, June 1943

A cable from Theo alerted Frank to her Arabic broadcast with the BBC Overseas Service on 4 January 1943. Negotiations had taken months, involving fees for writing and recording (ten guineas) and advice on stage fright. Her talk, beginning ‘I am Zahle-born-and-bred’, designed to attract Syrians to the Allied cause, mentioned that she had a son serving in the Levant. Theo and EJ, seated at one of Balliol College’s super short-wave sets, found she had misremembered the wavelength and so missed her own talk; Frank near Baghdad had better luck. The mess wireless was tuned in, his fellow officers disappointed that Theo didn’t end ‘H’are ya, Frankie!’ Frank, able to follow little, recognised her customary vigour: it was the first time for two years he had heard her voice.

In this fourth year of hostilities Theo and EJ’s younger son would also be drafted abroad. Despite Theo’s patronising efforts to get him to follow popular Frank and thus inherit his brother’s friendships ready-made, he left for Algeria. Frank pictured him lugging suitcases to a waiting taxi, nipping into the kitchen for a sandwich and one last glass of milk while EJ scuttled across the croquet lawn in slippers for a book EP simply had to read on the voyage while the Great Muvver called out of the bedroom window: ‘Aren’t you taking your gasmask?’ EJ provided his own vignettes of home life, depicting Theo as ‘acidly witty’ and meek only when she burned a saucepan or was caught simultaneously in two motoring offences. Coming across her typewriter unawares with a letter beginning ‘Darling Frank’, he inserted the words ‘I wish I were a good Muvver.’ Simple jokes leavened wartime privations.

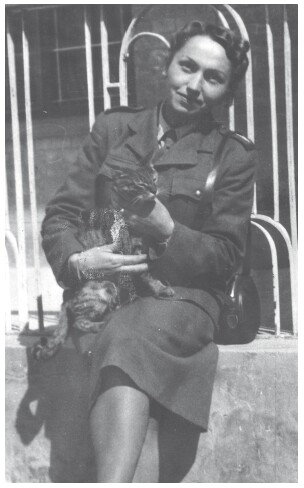

EP and Sandy, 1943.

‘Pre-war’ signified happy. When in February the exiled King of Greece joined Oriel high table, EJ enjoyed ‘a pre-war dinner’. Next month Theo unlodged a box of pre-war sweets but pronounced them ‘bad for his throat’. In May they attended the wedding of a private secretary of Churchill’s whose bride wore a pre-war wedding gown – wonderful for Theo to see – costing seven clothing coupons only. Clementine Churchill was there plus Brendan Bracken with his enormous red wig-like mop of hair obstructing EJ’s view. Everyone wanted news of Frank.

After four years of war Theo noted that mothers meeting casually hesitated to ask after each other’s menfolk, lest there be bad news, or no news at all. Nancy Nicholson’s son David Graves was killed in Burma. Then Frank’s Dragon contemporary Andrew Gardner, of the Boars Hill gang, was in August 1943 found dead by his bike in Oxford, aged twenty-one. Theo wondered whether such a non-war-related death might be even worse for the family.64

EJ ‘moiled and struggled on alone’ that year, campaigning about the famine in Bengal. Around three million died there, in part because the British were exporting Indian rice to the Middle East – a crass and shameful return for Indian loyalty. EJ ‘busked an interview’, in Theo’s expressive phrase, with the new Viceroy, General Wavell, who told him that the India Office denied that the famine was real.

Storm Jameson, as we have seen, wrote of the intransigent idealism of both Thompson boys. Idealism can cause priggishness, whose comical effects were on display when Frank rebuked his batman Lorton for not getting excited about seeing Jerusalem. Frank in a poem celebrates two Lorton-like squaddies in conversation: ‘“Well Bill? Yer glad yer came out East?” / “Ho yuss! I wouldn’t have missed this for quids!”’, glossing this exchange: ‘Oh England! Oh my lovely casual country! / These are your lads, English as blackthorn-flower . . .’ The same affectionate Wykehamist paternalism prompts Frank to record Lorton’s claim to have had ‘an inkling of Latin’ at school when he meant a ‘smattering’.

The errors of the educated get corrected too. Frank fumes against the semi-literate officers who think every Jew a cad best off underground, and every striker deserving to be shot: he was as indignant as if he were a Jew or striker himself. He rants against the ruling-class English – finished as world leaders, tired, dishonest, moral cowards without imagination, who had lost all capacity for idealism or adventure, enjoying second-rate pleasures. He raged against his fellow officers. Only Donald Melvin, an ex-solicitor with whom he had sailed out on the Pasteur, had never put his mind to sleep, but Melvin was now dead. One fellow officer scorned the idea that the war was being fought to make a better world afterwards: if it were as simple as that why not stage a world war every twenty years to guarantee steady progress? This joke gave Frank pause. Officers displayed a sickening lack of curiosity about the countries they were living and fighting in. With such leaders it was small surprise that their men had no pride in the struggle for human liberty and were apathetic about seeing the beauty or learning the history of the Middle East.

Four dismal and hateful winter months in Iraq in 1942/3 were made worse by Frank’s having to take charge for five weeks while Grant retrained. Happily the tide of war was turning in the Allies’ favour. Before El Alamein in November 1942, as Churchill later quipped, the Allies enjoyed no victories – and afterwards suffered no defeats. Taken together with the agonising Soviet victory at Stalingrad, it at last seemed probable that Germany might lose the war.

An improvement in airmail speed followed these Allied victories: a letter of Frank’s dated Tuesday 27 April arrived in Bledlow on Wednesday of the following week. This did not merely make communication much faster – ‘almost like peace-time’ – but enabled those quarrels that needed recent anger or live resentment to fuel them. Correcting each other’s errors of spelling and grammar was a standard Thompson joke. Frank blamed one altercation with his father on his own ‘violent childish tangent’ about RAF ground staff after he had very nearly been killed by the panic-stricken driving of one a fortnight before. It is notable that he does not dream of holding his father to account for this argument, blaming his own ‘childishness’ instead. In October 1943 he confessed ‘au fond I’m still hopelessly childish and it breaks out now and then’.

If Frank stayed childish, EJ helped keep him so. When in 1942 EJ had a story of Frank’s published in Time & Tide and another in the Guardian, or a selection of his letters in the New Statesman, he gave Frank no prior warning of publication – as Frank remarked to Iris. Perhaps he saw Frank’s writing as an extension of his own. His attitude helped inspire a crisis Frank underwent in 1943. Its roots in his father’s censure, in his relationship with Poles and in Iris’s embarkation on a love-life that necessarily excluded him are worth examining.

His father sent him on 5 April 1943 a stinging rebuke. While praising the generally high standard of Frank’s ‘superb’ letters as, at their best, ‘natural easy prose, as matter, and as poise and self-carriage’, he indicated that his late 1942 Teheran visit had seen a deterioration to, in EJ’s damning phrase, the telling of ‘a desultory story’ entailing ‘third-rate ways of amusing yourself and drab companions’. He and Theo would not be altogether sorry if Frank presently got himself into ‘a livelier and usefuller life’. For ‘desultory’ read ‘unheroic’.

This conceited letter hurt and dispirited him, but Frank (typically) did not say so. Nor did he remark on the implicit assumptions that his war was being fought for his father’s entertainment and that he was a free agent. EJ’s early drollery to EP – ‘Kill an Italian if you get the chance and I promise to pay the fine’ – conveys similar assumptions. For Frank’s enormous output of letters home from March 1941 was indeed designed to entertain as well as reassure, a performance-art for domestic consumption. Frank had apologised for one long discursive late-1942 letter as sounding ‘pretty stupid but I so rarely give you an hour-by-hour account of my doings, I thought it might amuse you’. EJ was not amused.

He and his father held many assumptions in common, and Frank travelled with the collection of his father’s books that had impressed Peter Wright. He met few officers who had heard of his father: EJ’s taunts that he never read his books notwithstanding, he studied and referred to them frequently. Frank devoured Crusader’s Coast for its account of Levantine plant life. He re-read and admired An Indian Day, requested and got a copy of Burmese Silver, and appealed in his diary in June 1943 under his page-header ‘THE DEATH-WISH’ to his father’s novel These Men, thy Friends as a source of wisdom:

When I think myself reconciled to the idea of dying, is this merely the death-wish, a defeatist attitude to the complexities of life? Don’t think so. Normally I take a healthy pleasure in living & still have a great many ambitions. One feeling I must fight – ‘At least, if I’m killed, then everyone will think well of me.’ Despicable this, revealing complete selfishness & inability to imagine the sorrow one’s death might cause to one or two people. I seem to remember something very fine in These Men thy Friends where Colonel Hart gradually masters his soul in the face of death, must read it again.

Frank’s admired father had won the MC for bravery in Iraq twenty years before, and as an established writer addressed this experience in These Men, thy Friends. Frank elected his father mentor in questions of life and death and the courage required for both. After EJ had tried to write a play about the Buddha, Frank often declared himself sympathetic to Buddhism.

He wrote home warning of the importance of receiving letters for his well-being, mentioning queer moments ‘when it’s almost impossible to believe that one has kinsmen anywhere’. Theo sensed that he chivalrously hid his dejection for months at a time so as not to demoralise others,65 and tried to jolly him into realising that he had three relatives in England who adored him – ‘and not to mis-conceive one remark of Dadza (about “desultory living”) as intending to deprecate you, Frank’. Thus she identified the precise phrase that had wounded him.

EJ also asked Frank why death removes the fellows he does, leaving alive those who are ‘long ago rotten-ripe for cartage to the dust-heap’. He thus proclaimed himself somehow ‘finished’, living vicariously only through his sons. He was ashamed that his own war was so unheroic and ‘desultory’; no doubt he projected this shame on to his sons, together with a wish for them to excel in his place. True, to both sons during 1941 EJ wrote facetiously, ‘“Let them as wants their bloody George Crosses ’ave ’em” as a Princes Risboro sergeant observed.’ Yet a countervailing rhetoric also obtained.

Iris, as we have seen, purveyed precisely the same double message, insisting that she should only like Frank to be a hero if this could happen ‘without the necessity of a vulgar display’, yet praising T. E. Lawrence’s swift life of action and, as we have seen, calling him ‘the sort of person I would leave anything to follow’.

Both EJ’s injunction to Frank to dedicate himself to ‘a livelier and usefuller life’ and Iris’s cheerleading came at an interesting moment. That April Frank first heard about the Special Operations Executive (SOE), another irregular formation, dreamed up in 1940 by Churchill, that invincible romantic,66 to coordinate action against the enemy by means of subversion and sabotage, including propaganda. British liaison officers or BLOs were to drop into occupied Europe to help ‘set it ablaze’, and films such as Heroes of Telemark and, more recently, Charlotte Gray present a glamorous picture of their work. It is worth noting at the outset that SOE’s leading historian (and Frank’s friend) M. R. D. Foot doubts that – morale-boosting apart – SOE achieved very much. And yet surely the value of morale itself in wartime is incalculable.

Frank, in any case, was immediately attracted and excited, making the final move that September in order to fight in Greece, which always represented liveliness and usefulness. SOE was the exact opposite of ‘desultory’. It added a tincture of dangerous adventure that might satisfy even so stern a task-master as his father. And so he wrote, ‘I agree with Da about desultory living – not one of us shed a tear on leaving [Persia].’

Another factor making Frank feel that his war had thus far been desultory and unheroic was friendships with Poles, who he declared in 1942 ‘had suffered more than any nation in Europe’.

In woods outside Smolensk in April 1943 German soldiers found graves with the bodies of some 14,000 Polish officers67 murdered two years before by the Soviets. When Germany broadcast this, Stalin lied that these Poles had been murdered by Nazis in 1941. And Frank believed this Soviet lie. He thought Nazism in its death throes was blackening the Bolsheviks as a bogeyman to frighten the West and win allies, and that the Poles were ‘tactlessly’ taking the Germans at their word.

Before judging Frank too harshly it is worth recalling that the truth about what we now call the Katyń Massacre was admitted by President Gorbachev only as recently as 1990, when he confessed that the USSR had wanted to destroy or damage Poland as much as did Hitler. Frank’s refusal to believe that the Soviets murdered these (and other) Polish officers was shared by many at home who feared that Poland would endanger Allied unity. His father criticised the ‘unreality’ of Polish ambitions and Poles’ ‘swelled head’ about erstwhile glory and lost territories while Iris in 1945 lost her temper with an anti-Yalta Pole.

Meanwhile, the Polish government-in-exile in London demanded an independent examination of the recently discovered Katyń burial pits, following which Stalin used this threat that his responsibility for the mass murder he had ordained might be revealed to break off diplomatic relations. Idealistic Frank, noting (typically and optimistically) that the Russian writer Pushkin and the Polish poet Mickiewicz had both liked one another and also been bullied by the same Tsar, was flummoxed.

He had first sighted Polish officers in the Western Desert in 1941, and he accounted himself a ‘keen supporter’ the following spring of the tens of thousands of Poles who had escaped with Colonel Władisław Anders from the USSR,68 gathered in camps near Teheran. He started to learn Polish as well as Russian – a feat notoriously vexed by the kinship between the languages; given the large number of Polish troops in the Middle East, he thought it might come in useful. He mock-modestly boasted that his Polish was at first so simple that he could use it ‘merely on the telephone, to wage a political debate, or to discuss pre-Raphaelite painting’.

Admiring Polish courtesy, charm, sense of fun and courage, Frank made new Polish friends. Notable was Emilia Krzyprówna, aka Mila, an Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS) corporal in Paiforce in Iraq, whom he taught English while learning Polish himself. Mila had been an unambitious civil service clerk from a comfortably-off Kraków family when the Russians and Germans invaded in September 1939. Strafing by German planes meant that her evacuation eastwards to Lwów took a nightmare three days instead of the normal three hours. In the USSR she became a road worker. Although in August 1943 Mila discovered after four years a sister called Anna living in Gedera in Palestine, she had reached Persia in 1942 alone and with nothing, unsure whether any family at all had survived. ‘Quite fairly pretty,’ Frank called her hesitantly, adding chivalrously ‘first-class smile’ and classifying her as one of the ‘little people’, backbone of this anti-Fascist war, who gladden his heart. Frank and Mila exchanged photographs and affectionate letters in Polish, and Iris noted his closeness to a Polish girl whom he called by the warm diminutive ‘Miluska’ and who sounded nice and allowed him to ‘thou’ her. (Meanwhile EJ warned, ‘Don’t think too much of Polish girls.’)

Then there was the interpreter and writer of Polish children’s books Życki, whom he had first known in Persia, who shared Frank’s surreal humour and who discovered his own younger brother in Baghdad. He talked to Frank about recent Polish history and embarrassed him by dancing a krakowjak, a vast moon-faced man of forty doing a ludicrous hornpipe in battledress among the palms, or rushing forward on all fours to show how he had stormed a Bolshevik barricade near Lwów. And then Piotr Adamski, also approaching forty, whose twin brother was a prisoner of war in Germany – where Frank noted that Slavs did not survive long in captivity.

‘This cat – for my Dear Teacher, Mila’, 14.vi.43.

Frank understood Polish fear and hatred of Germany and of Germans very well and joked about it. English officer: ‘Once the war is over there can be no indiscriminate killing of Germans.’ Polish officer: ‘Certainly not! It must be thoroughly well organised!’ Yet he could not ‘read’ Polish–Russian relations and believed Poles out-and-out liars about Russia. His father commended his simile about Poland having the ‘vitality of a hawthorn hedge that has been cut and laid – times beyond counting’, but Frank somehow overlooked Russia’s role as a leading Polish hedge-trimmer.

The Poles, ‘rabid nationalists’ spreading ‘envenomed’ propaganda, had been telling atrocity stories about their internment in the USSR, propaganda that went on twenty-four hours a day and under 1,000 horsepower pressure. Frank protested that the Russians would not have deported and interned ‘a few hundred thousand’ Poles without reason. Deportees from the landowning and commercial classes had a ‘bad record’ – that is, were reactionary – and so were unlikely to be willing to help shore up Soviet defences, and ‘justice meted out to a class takes precedence over injustice to individuals’: a startling, dislikeable and unique instance of his talking like a loyal apparatchik. While it is true that Polish deportees were required to perform menial labour in the USSR, this contrasts favourably with the ‘criminal softness’, in Frank’s view, of the British towards Fascists interned on the Isle of Man. He appears unaware of his own implicit and insulting analogy between Pole and Fascist. While Poles complained of hunger, fatalities and filth in the USSR, photos of Mila in Russia showed her looking fit and well, and while he acknowledged that some Poles did arrive in Persia lice-ridden he pokes fun at Mila’s petit-bourgeois indignation when he asked her if she had been lousy.

This issue of Polish–Russian relations helped split the Iraqi Communist Party, and Frank got involved that winter in attempting to heal the divide. He was shocked by the constitution of Iraq, a British puppet state whose military dictatorship recognised neither political parties nor trades unions; even the right to form an anti-Fascist league had been refused. Underground parties circulated papers, but the printers were liable to arrest, their presses to confiscation. Only one left-wing paper existed legally. The Iraqi Communist Party with its small following of Baghdadi shoemakers organising illegal unions was backward, possessing in Arabic only the History of the Bolshevik Party, thumbed through in each crisis for advice.

The Polish forces’ ‘great anti-Soviet propaganda campaign’ was having some effect, and two factions of the Iraqi CP, split over how to elect leaders – as almost certainly over the truth of the Katyń Massacre – attacked each other. Frank tried to help. First of all he wrote that winter about Polish anti-Soviet propaganda anonymously and influentially in two rival underground Iraqi CP papers, analysing and exposing it. While these articles don’t survive, their gist is captured in a letter home.

After discussion with other sympathetic people, Frank and Jacobson, his Phantom colleague, arranged a meeting under Frank’s chairmanship, his word to be final. Frank and Jacobson told the Iraqis that their squabble was hindering the progressive struggle, and worked out a joint programme. Frank also helped them elude censorship and establish contact with the older Syrian CP, which promised books and advice once unity could be demonstrated. But neither side was willing either to publicise the fact that such an accommodation had been reached or to join forces.

This is the only moment when we glimpse Frank’s CP activities: consulting with unnamed British CP members, chairing Iraqi CP meetings, helping the membership elude censorship and opening channels of communication between Syrian and Iraqi CPs. Small wonder that EP’s detailed 1946 report after meeting Frank Jacobson advises his parents to omit all this from the family’s commemorative There is a Spirit in Europe: ‘Most of this was outside Frank’s range of duties(!)’ The exclamation mark is EP’s: article 451 of the King’s Regulations forbade any serviceman from participation in the affairs even of mainstream political parties, let alone the CP.

A new field of speculation opens up, like the one we glimpse on learning that Iris Murdoch as an assistant principal in the Treasury had ‘borrowed’ and copied state papers which she took to dead-letter drops in a tree in Kensington Gardens. This happened probably during 1943 and 1944. The Party was quite capable later of blackmailing members whom it had thus enticed into betraying official secrets. We sense a darker world, remote from our own.

If Frank had survived the war with his political passions intact – a leading question – he was exactly the sort of exploitable public school product the Communist Party often groomed as agent or spy. His friendship with Mila while repudiating and despising her politics is rare evidence that he might have been capable of active duplicity beyond conventional politeness or diplomacy. Yet this deceit – if it can be so described – had limits. When he was visiting Mila at her ATS hostel for an English–Polish lesson, one girl by mistake switched on the ‘Internationale’ on the wireless. The ensuing shrieking and slamming of doors by some dozen other Polish girls disturbed in varying stages of undress by this anthem of the detested Soviet enemies who had deported them made him ‘laugh until he nearly broke a rib’ and Mila had to rebuke him. He took no trouble to disguise the mischievous pleasure he took in their discomfiture.

Frank has few hallmarks of an agent. Not merely did he have no right-wing cover or front – unlike Guy Burgess and Kim Philby, who deliberately joined the Anglo-German Fellowship to disguise their real leanings, or Bill Carritt’s beautiful wife Margot Gale – but there is nowhere that Frank did not announce his politics or ensure that these were widely known and understood. EP believed that Frank was not in touch with King Street – the CPGB headquarters. Nor is it likely that he spied for the USSR or had a Soviet controller. During his three years abroad he rarely spent more than five to seven days in any one place before being moved on unpredictably: the nomadism that prevented settled love affairs rendered double-dealing difficult too. His four months in Iraq – like his six weeks in Iran before being hospitalised for jaundice – were very untypical.

His period of busy CP activity overlaps with his five weeks of command in January–February, when the unit idled, George Grant the senior officer was away retraining, and Frank was acting CO, hating – at twenty-two – this ‘nightmare of command’. Nor was Frank a loyal cadre. He lacked blind faith and could not quell his habitual independence of mind.

He found it difficult to read Iraqi history, which he thought simply dire, with the ‘positiveness’ that his Communism demanded. Iraq prompted in Frank aversion and despair. True, his liver was weakened from hepatitis and he drank now only in company, noting his parents’ fears that he might become alcoholic: his view was quite literally ‘jaundiced’. Acknowledging his being ignorant and ‘not quite balanced’, he thought the Middle East ‘misgoverned and demented in a thousand ways’, where men for millennia had been born and died among flies and filth and stench. Iraq was the worst. In summer a furnace withering men’s souls and in winter a bottomless damp mud that made one feel one was rotting away – it was impossible to feel fit there. ‘This is not a country that men should be expected to live in.’ The gulf between locals and the soldiery depressed him too.

A water vendor drinking water scooped from the drain running down the middle of the street filled him with horror, and Islam itself seemed not merely ‘bogus’, but the death-wish incarnate. He wrote to Iris that, as with his father before him, ‘the utter poverty and human degradation is a thing which comes to weigh on the mind incessantly, until one can get joy from nothing . . . The misery of the east is a thing which you cannot imagine.’ He had an especial detestation of Muslim funerals and widows with their ‘dry hysteria’: death should not be allowed to corrupt life with its sterility, or allowed more dominion than was its due.

Iraq made the Western Desert seem by comparison ‘like Buckinghamshire’, while Baghdad was the devil’s residence, without a single street that would not shame Princes Risborough – homesick analogies. The poverty, the worst he had ever seen, nauseated him, dirt and chancres or body-sores reigning everywhere. He took his stand on complete independence for Iraq, adding prophetically, ‘don’t force any Englishman to go near the place’. Like Iris he adopts at times a note of tragic humanism entirely at odds with ‘official’ Communist optimism.

So, despite mouthing the rhetoric to the Iraqi CP that ‘justice meted out to a class takes precedence over injustice to individuals’, he refused in practice to treat all Poles simply as reactionary enemies of progress. To his parents and to Iris by contrast he detailed the sufferings of individual Poles instead. Frank and Adamski spent all Sunday afternoon on 7 February 1943 sitting in a café, meditating on the basic sadness of life. Adamski let Frank read a letter from Tosia, his fiancée, still in Poznań in German-occupied Poland where he feared for her safety. The dry ink of this letter seemed to ache with restrained longing and a courage maintained only by the most rigid self-control.

Cut out all sententiousness about strength through suffering. Think of the millions of people to whom this war has brought nothing but utter irredeemable loss. Piotr and his Tosia are both close on forty. If the war leaves them both alive and sane, they will still find little peace in an embittered and factious post-war Europe. For us, who are young, and have the faith that we can recast the world, the struggle that comes after will be bearable.

Frank felt very deeply for the countless peaceable people who could never, because of age, upbringing or environment, wholly join the progressive struggle and ‘would never know peace in the one short life allotted to them’. This mature breadth of sympathy is remarkable.

Mila’s predicament in exile in a labour camp in the Urals the previous year moved him too. Her country had ceased to exist and her whole family had suffered under German occupation. Yet instead of sympathy in the USSR she met with a new hard life, surrounded by a race of ‘rough, straight-forward, mildly inquisitive bears’. He listened for hours to Mila’s imitations of the deep-voiced Russian peasants (muzhiks) who yelled at her that she was a wealthy bourgeois who had ‘tortured the people’.

Mila could not have tortured people if she’d tried, though he picturesquely adds that her landowning family ‘must have done so often’. Frank imagined her slaving blamelessly in an office every weekday, in order to go dancing on a Saturday evening and ‘lie in’ on a Sunday morning. He pictured her arriving in Sverdlovsk with three trunks and two fur coats, an orphaned white-collar girl whose country had just been bombed and whose life had been smashed to pieces from under her. The Russians, he argued, would have done better to appreciate that a) nobody except the most vicious criminal should be made to feel that the whole world is against them, b) an individual does not always react along with her class and c) ‘in a world as filthy as it is today, one should remember how helpless and how lonely the individual is, and that kindliness, especially when it costs so little, is a policy that justifies itself’. Noble sentiments.

He brooded about Mila and the fate of others like her. Twelve weeks after this letter, and long after parting from Mila, he is still complaining to Iris from Egypt about how she was treated in Sverdlovsk. He could still quote verbatim Russian insults shouted at her. ‘How stupid class generalisations sound when applied to individuals.’ However much we steel ourselves to hate institutions and even bodies of men that are striving for evil ends, there was no point in trying to hate men. ‘We’d be wasting our time . . . Worse than that – we’d be losing our own virtue,’ he admonished. (It was in a similar vein that he had chided his brother that July: ‘It’s a mistake to hate people because of their class.’)

That Frank at twenty-two understood that hatred entails loss of virtue is reason enough to honour and admire him. That he wrote in this style to both Iris and his brother EP, both more loyal CP activists than he was, makes clear how impossible it would have been for him to conform to any dogmatic Party line. He was too much of a rebel to obey the rules.

His new Polish friends taught him another lesson, too. Frank reckoned that, exile abroad and the deaths of friends apart, his war had been easy. The Poles had by contrast suffered greatly. Was it perhaps Frank’s moral duty to suffer more?

Frank was responsible for administration, supplies and discipline, ‘just like Muvver at Bledlow’ he quipped, but could not get very excited about wrestling with a soldier’s marriage allowance or finding out why the Quarter-Master Sergeant (aka QMS) overdrew rations. His additional role as the Unit Education Officer, however, offered his political passions a creative outlet. The Army Bureau of Current Affairs (ABCA), founded in August 1941, purveyed a new and often radical concept of adult education in the Middle East, especially after Alamein, when it became notorious for spreading socialist ideas, triggering Churchill’s hostility for that reason.

He and his fellow Communist Sergeant Jacobson invited lectures from the men: an old India hand gave a talk on snakes. Then Frank staged a quiz when, as Brains Trust question master, he was startled to find only ‘trick-questions’ or riddles submitted, designed to catch others out. He patiently explained that the purpose of discussion was the quest for truth. He was pleased at the turn-out despite the men’s suspicions that he was serving them ‘propaganda’.

That Frank’s politics were well known is clear from a Poetry Prize competition he organised. A fellow officer submitted a very promising poem as if from one of the men, waiting for Frank to talk excitedly about the genuine reserve of poetry latent in the masses before revealing the practical joke. Frank had the previous year mounted a so-called Wall Newspaper about the USA, made up out of newspaper and magazine cuttings and his own captions, entitled ‘Salute the Yanks’, which explained that although the USA, as could be seen from John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, had poverty and unemployment like England’s, it none the less had also a healthier spirit of democracy than England’s, and an impressive history of struggle against oppression.

Now Frank and Jacobson’s Wall Newspaper entitled ‘Life in the USSR’, using cuttings from the special 29 March 1943 issue of Life magazine that Theo sent out to him, with its soft cover photo of Stalin, can have left little doubt about his political sympathies. While his QMS made snide innuendos to the effect that he suspected Frank of being ‘Red’, Frank in his turn guessed that a new Phantom officer named MacIver had Communist sympathies because he was reading Tom Wintringham’s English Captain. Wintringham, once in the CP and now promoting the new Common Wealth Party, had visited his parents at Bledlow and Frank noted that his 1939 novel about Spain was mainly still read by those sympathetic to the CP.

Frank gave talks too. On 12 January 1943 he spoke on occupied Europe, a topic on which British newspapers said little, but as a self-taught expert he was frequently quizzed. He made terrifyingly clear what was at stake. His marathon covered some fifteen countries in (roughly) the order that they fell: Germany itself, Austria, Spain, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Denmark, Norway, Holland, France, Hungary, Romania, Belgium, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Greece, Italy, Finland – instancing collaboration and resistance in each. He detailed the murder by the Nazis of 54,000 Jews at Babi Yar near Kiev, followed by the killing elsewhere of one million Jewish men, women and children by machine gun, torture, hunger and what Frank quaintly calls ‘lethal chamber’. We now know that by October 1942 more than two million Polish Jews had been murdered, but the Wannsee conference decreeing the Final Solution had happened only one year before, so Frank’s talk, based on the Daily Worker, the newspaper Soviet War News and listening in to Moscow Radio, was comparatively well informed. Being in an intelligence unit doubtless helped.

This talk was a tour de force. Intended to be one hour long, it lasted for two but nobody yawned. Frank’s passion for explaining exactly what a Nazi victory could mean for his listeners’ families – slave labour, starvation, torture and mass murder – compelled his audience. He left them in no doubt that the future of humanity itself was at stake in the coming struggle, his picture of course the simplified one favoured by Hollywood – a fight between Light and Dark, ignoring Allied disunity and Soviet brutality towards the Poles (and Finns) in particular.

The following day he staged a debate on the motion that ‘Germany should for world security cease to exist after the war’. It was defeated by fourteen votes to four, a common-sense outcome that pleased him. He was never what was called a ‘Vansittartist’, one who believed that the complicity of all Germans in aggression must be punished by violent and total defeat. Eighteen was also a large turn-out for an entertainment devised by an officer. He understood the resentment felt towards officers and – while he never bought into Marxist cant about ‘the inevitability of class-struggle’ – thought such resentment natural. He also gave a talk on the make-up of the modern German Army, whose professionalism and tradition of conscription he admired and thought the UK could emulate, albeit not the German tradition of expecting blind obedience from troops kept ignorant of war aims and strategies.

The Beveridge Report had been circulated in December 1942, with its blueprint for a post-war National Health system. Frank naturally approved, despite fearing that it did not go far enough. Its assumption that a pool of unemployed would continue, guaranteeing cheap labour, Frank found offensive. He preferred G. D. H. Cole’s harder-hitting Great Britain in the Post-War World, which charged capitalist states with criminally sanctioning mass unemployment, international aggression and the rise of Fascism. Cole encouraged in him the belief that only force could dethrone capitalism and create a free internationalist post-war Europe where the means of production would be reorganised – the only time Frank appears to back the use of force in peacetime politics.

Beveridge none the less endorsed the hope that peace would inaugurate a new social order and provided a rallying point. Frank chaired a discussion on the report in April 1943 which he judged very lively and successful, confining an ex-Tory MP to only five minutes, making a pro-Beveridge speech himself and startling a bewildered Indian major who was amazed to learn that the British wartime Cabinet had in principle already accepted Beveridge.

His political isolation lessened after early April when his unit returned to Egypt. Here, to the alarm of the authorities, was a groundswell of radicalism. It was in Cairo that autumn, 1943, that the six monthly idealistic Forces Parliaments started.69 In Alexandria Frank got ‘very successful’ discussion groups set up in a number of the soldiers’ clubs, and invited speakers of various nationalities to talk about their own countries, sometimes speaking himself both on Beveridge and on ‘Who lives in the Balkans? And why is it so bloody?’

He observed the upsurge of discussions about post-war reconstruction, encouraged by their socialist tendency while deploring the prevalence of mouth-shooters. These activities generally cheered him up and made him more optimistic. He was touched that March to find that one officer had compiled a forty-page form-book for the local races plus an impeccable index, as also to discover two others huddled over the lamp long after midnight, checking and rechecking the evening’s poker scores. Perhaps he had underestimated the ‘tremendous reserves of energy’ such officers possessed after all?

In mid-April Frank’s unit, its vehicles undergoing repair near Alexandria after their epic journeyings, was shaken out of boredom by learning that a Special Assault Detachment was on its way out to help them get fighting fit by 1 August for the invasion of Rhodes and/or Turkey: Operation Accolade. Ten unfortunates were to learn Turkish, which did not faze Frank, who also arranged for an equal number to learn modern Greek, applying himself to both languages.

By June these plans were overturned and replaced by the Sicilian landings instead. The Special Assault Detachment under Captain Alastair Sedgwick, who had recently distinguished himself during the disastrous Dieppe raid, arrived in Suez. The only thing wrong with Sedgwick, it was jested, was that he was still breathing. Unpopular though Sedgwick was, Frank decided that he liked him so long as he ‘didn’t have to work with him’.

Before they set out, a cynical clean-up was staged to impress the inspecting Secretary of State for War, Sir Percy Grigg. Phantom H was now attached to the Durham Brigade of the 50th (Northumbrian) Division, the Eighth Army’s sheet anchor, despite enduring a typhus epidemic for weeks. Yet only Grigg’s visit procured them baths. The desert camp-floor was swept and prettified, unusually good food was served, and a wireless appeared in the men’s mess, still in its case so it could be packed and sent away again immediately after. The atmosphere of blatant hypocrisy depressed them all.

Montgomery gave a tired and uninspiring pep talk in a vast barn-like cinema on 24 June and Frank found him more likeable and less arrogant than he had expected, but felt his exhortations lacked warmth. He wanted Monty to congratulate them for what they had already achieved and to tell them he knew he could count on them in the coming battle. What they got was lacklustre.

They sailed on the Winchester Castle on 4 July, on board which, one day out, the men were finally told where they were going and handed copies of A Soldier’s Guide to Sicily. Frank’s own pep talk on the 9th to his five men, three of whom had never been under fire, went ‘I don’t think it’s going to be a bad party but there’s bound to be quite a lot flying about and you’re bound to feel frightened . . . The Brigadier will be frightened too . . . and personally I’m always scared stiff . . . but as the Major said “You’ve gotta overcome it.”’ This seemed to amuse them.

He could not drink himself silly even had he wished to: his jaundice-damaged liver protested and he distracted himself instead reading fruity passages from sixpenny novels. He encouraged himself with the belief that gentle people made the best soldiers, watched the officers make asses of themselves, and was greatly struck when the Durham soldiers sang ‘Keep yer Feet Still Geordie Hinny’: ‘Let’s be happy through the neet / For we may not be sae happy through the day. / Oh give us that bit comfort, keep your feet still Geordie lad / And divn’t drive me bonny dreams away.’ A working man forced to share his lodging-house bed berates his undesirable partner for waking him up just when he was dreaming of gaining the elusive object of his affections, Mary Clarke. The pathos of this comedy of frustration, and the men’s singing alike, moved Frank to tears.

Frank brooded about the coming casualties, as yet mercifully hidden from view; he imagined fearful Italians awaiting invasion exactly as he had done in Suffolk in 1940, and made himself unpopular going round telling and retelling his poor joke that the 9 July storms were caused by ‘four million Italians with the wind up’.

They landed in Sicily in the early morning of 10 July near Avola in the south-east, Etna’s cone clearly visible behind. He knew his perspective was unique. While his men feared Sicily as a barren, waterless, disease- and sirocco-scourged hell peopled with imbeciles and murderers, for him, by contrast, this was the island Theocritus, the Emperor Frederick and Matthew Arnold had all hymned, ‘an eclogue’ itself, where Pindar had eulogised the tyrants of Syracuse, and where Aeschylus lay buried at Gela. The interest of Frank’s notes on Sicily (later worked up into a 10,000-word diary) lies in how he sets moment-by-moment detail within this much larger picture, relating classical Greece to the coming defeat of Fascism.

On the belated night-time approach Frank encouraged his unit, dished out the rum ration, lit up his pipe.70 An overpowering smell of citrus and wild mint greeted them, followed by two accurate mortar shells fifteen paces behind, killing the crew of the landing-craft, setting the stern ablaze. Frank observed one AMLO71 officer drop to his knees, ashen-faced with terrified eyes. A tall lance-corporal striding a few paces in front fell groaning, his trousers suddenly turning bright red as if by magic when shrapnel hit him. Another in front limped and fell, an arm and leg pretty well torn off.

Frank, too busy to feel terror, helped his badly shaken men lug a cumbersome barrow through shell-induced twig-and-pebble showers and then, to calm them, into a safe wadi reeking of thyme, mint and lemon, encouraging them to start blackberrying. Looking at him a little oddly, they joined in. His description of the scene as ‘placid and unreal’ reads truthfully, as does his account of the healing mechanism that led him to fantasise a honeymoon return to Avola post-war, to show off the scene to his wondering bride.

Despite the navy having landed his brigade many miles off course, and some American parachutists suffering ‘friendly fire’ as a result, the English, ‘whom Europe understands so little and needs so much’ – a reciprocal state of affairs, he noted – ‘had returned to her after two years of absence’. A memorable day: on to the Sicilian coast of an enslaved continent, the promise of freedom itself had just landed. Frank settled to writing messages and to eating their excellent forty-eight-hour ration: one tin of bully, biscuits, dripping, raisin chocolate, boiled sweets, ‘tea-sugar-and-milk-powder’ brewed on a small aluminium Tommy cooker fired by petroleum gel.

He disapproved of one British patrol looting ‘records, gold rings, god-knows-what’. Though thinking himself an ‘Old Soldier’ he hoped he never became as hardened as that. Indeed he spent hours tramping out of his way because a boy of sixteen had had his tuppeny-ha’penny watch stolen by a British soldier and he hoped to find the guilty party. He meditated mordantly that when the Germans conquered an Eastern European town, they, by contrast, shot 50,000 inhabitants and sent the best-looking girls to military brothels.

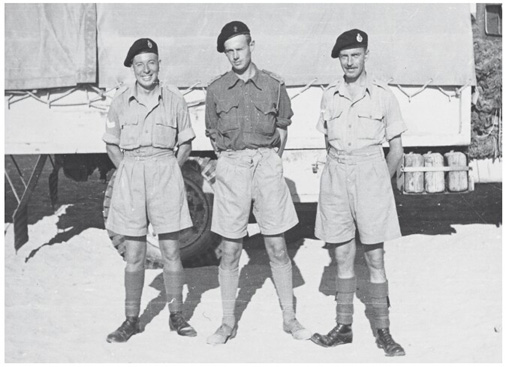

‘“Self ” between “Spud” and “Sam”, my two wireless operators on the Sicilian landing. Two of the gentlest creatures who were ever made NCOs even in our civilian army, and, as is the way with such people, quite fearless.’

The Sicilians he met were hungry, and he forecast (accurately) that food-ships would relieve them soon. Meanwhile he and his men enjoyed local tomatoes and wine and marvelled at the speed with which Italian soldiers, having practised gangster-killing by shooting men in the back, threw down their arms and made a grand opera of surrendering, sometimes bursting into tears.72 There were Stuka attacks, and also Stukas shot down, and further Bofors shells especially on the port, and ferocious midges at night, but Frank often slept well before his departure on 15 July for Malta, too lazy on occasion to dig himself into a slit trench, though requiring his men to. Sicily fell by 17 August and Italy surrendered on 8 September.

This was Phantom’s last makeshift campaign. One historian paints a chaotic picture of bad communications on their voyage out, during their five-day stay, and again on leaving Sicily, when H Squadron split into three parts, with Frank, five other officers and fifteen other ranks marooned for a week on Malta, maddened by a stream of orders and counter-orders directing them first to return to Sicily, then to fly to Sousse in Tunisia, next to go to Alexandria and finally to ‘stay in Malta’ at all costs. It took until mid-August for the squadron to reassemble in Egypt, after three weeks in Tripoli.

Frank’s first aeroplane flight – Malta to Tripoli – alarmed him considerably. He marvelled at the uneasy sensation of flying as at the lack of identity checks and feared that any German agent could fly on British planes without being questioned once, from Senegal to Teheran. He thought flight a bad augury for the planet’s future. It was too fast and too precarious. It made him feel old-fashioned.

On 14 June Theo had written, ‘I think we have the right to hope that we may see you [next year], Peace or no Peace. The only danger . . . is that the sight of you walking in the gate might give us heart failure from sheer joy. Such strong joy after such long waiting would surely do something to us . . .’ It seemed to Theo and EJ that both their sons haunted not only their daylight hours but even their dreams during the night, in equal measure.

Theo’s phrase ‘strong joy’ inspired him on Malta to scribble another rapid poem, surely one of the best verses on the great wartime theme of homecoming. Here he renders the pain of exile and longing for peace and restitution of normal family life intensely personal, before universalising them once again as aspects of a Europe-wide condition. His poem represents the best of Frank, his twin abilities to make the reader feel intimately addressed, and then also suddenly make himself vanish in the final two lines, turning into an oracle for his generation:

Will it be like that? Will the train pull into the halt

Below the Barleycorn, wait while I dump my kit,

Then chug away to Chinnor? Will all of you be there?

Can you fix it like that? Gods of the Chiltern Woods!

Will it ever be like that? I doubt it.

Shall we climb the hill together, the four of us,

Between the hawthorn-hedges, not breathing a word of war

Or dreary desert, discussing important things,

A name for our new cat, the apple-crop,

Bee-orchids growing on the Coneygar?

Will it really be like that? God Wotan grant it!

Tea with lemon by the lavender bed,

To be at peace, not trying to be a soldier!

The cornfield rippling in the evening light.

Among known walks, not feeling myself a stranger!

In that cool haven of my yearning

To rest with eyes half-closed and savour,

Along with millions Europe over,

The still strong joy of our returning!

His inclusion of place names stopped Frank on grounds of security from sending this wonderful poem home. His parents for the first time read it – among the last he wrote – after his death.73 They would have loved the twin irony and constraint of ‘important things, / A name for our new cat’. How vividly he conveys the pathos of yearning to be allowed to stop ‘trying to be a soldier’ and everywhere ‘feeling a stranger’, the pleas of so many conscripted men. But he had one year more of both to endure.

During his three weeks in Tripoli Frank found himself one day queuing for lunch next to his first cousin Trevor Vivian, an ‘exceptionally nice, modest lad’ wounded at El Alamein, after which he had blown himself up experimenting with a mine detonator. Trevor talked with nightmarish insincerity about the ‘good fun of fighting’, asking ‘what fun Frank had had’.

Frank confessed to feeling very frightened, on occasion nearly sick; he would be happy never to hear of another man killed or family bereaved. War could only be enjoyed, he reflected, at the expense of one’s humanity. He visited fellow officers in hospital, some grievously wounded in Sicily, and reflected on the dishonesty of most war reporting with its references to laughing, eager Tommies, and proffered his own Sassoon-like parodic rapportage of the Sicilian landings, in which the bullets lamming into one man’s head rip it open like a shell of ripe peas: not much fun there.

As for poor Trevor, he would the following month win the MC for knocking out four German tanks during the Salerno landings and, in a flying accident in March 1946, be killed.

Frank reported to his parents that Iris had become an assistant principal in the Treasury after she won a First, and that war had saved him from the indignity of gaining a degree inferior to hers. Admirers of Murdoch like myself are inclined to make much of Frank’s and Iris’s ‘star-friendship’ – Nietzsche’s phrase for affinity complicated by distance, a life-habit of hers – appropriating Frank’s fascination to her cause. When I wrote her Life and learned that Frank in Egypt started studying Turkish concurrently with Iris in London I assumed that this was Frank’s way of serenading her at long distance. I now know that Phantom HQ’s April 1943 directive required H Squadron to learn Turkish in preparation for the possible invasion of the Dodecanese Islands.

Turkish apart, much linked them. Both were brilliant would-be writers of omnivorous curiosity, lovers of Shakespeare and Communists marked by the ‘heroic struggle’ for Spain. Both were romantics. Iris Murdoch in March 1943 wondered what the future held for them all: ‘Shall we ever make out of the dreamy idealistic stuff of our lives any hard & real thing? You will perhaps. Your inconsequent romanticism has the requisite streak of realism to it – I think I am just a dreamer.’ In 1939 Iris had been Frank’s chief muse and inspiration. Increasingly in 1943 he was hers. His soldier’s life abroad made him grow up faster than her. She acknowledged an ‘understanding’ between them: ‘I feel in a peculiar sort of way that I mustn’t let you down – yet don’t quite know how to set about it.’

One aspect of ‘letting Frank down’ was taking lovers. She soon confessed that there had been two men, neither of whom she loved, and that she was happy at having set aside her burdensome virginity. She wrote with the confidence of one who has hitherto enjoyed the emotional upper hand but who now fears that her news – albeit itself a token of trust and esteem – might ‘anger’ him. He replied on 26 April that only jealousy or righteous indignation could be a cause for anger and that he had no right to either, not having thought of her as a body for four years, and having messed up his own love-life too: dividing women into distant princesses to be idealised and ‘tarts’ to be used.

The chilly, virginal Iris he had known two years before had given way to the promiscuous Iris of the dozen years leading up to her marriage in 1956, when sex seemed to her an aspect of friendship and often led to confusion. He claimed to feel ‘joy’ on her behalf that she had been rescued from her icy virginity, but issued warnings. She should beware of the contempt and hatred of men, especially those to whom she gave herself. On the whole Frank thought:

that it is better to abstain altogether until one falls head over heels in love. Men who had never slept with anyone before their wife, tell me that the first weeks of their honeymoon were an ecstasy they have never known before or since – an ecstasy which those who have already partaken of the fruit will never know.

For all his bohemianism and Communism, Frank was a conventional product of his class and time. When that December Frank inveighed against wartime adultery, divorce and people making ‘a mess of their lives’ a Miss Papadimitrou74 commented more in sorrow than in anger that Frank was ‘very old-fashioned’. He did not disagree. His standards of marital fidelity were, he confessed, ‘1860 Baptist chapel’.

His leisure occupations in summer 1943 – visiting the races, a concert of classical music, playing tennis, joining the Anglo-Hellene club, eating quantities of cake – are unremarkable and, apart from visits to the Greek theatre, conservative. If he was secretly active in the CP in these months, no record of this survives. He disapproved of air travel, of the infantilism of Hollywood and the Andrews Sisters, and censured Americans for keeping their (superior) Forces clubs closed to their allies when British ones were open. Such views could all have been voiced by his father, then bemoaning the lonely, girl-hungry GIs lounging all afternoon outside the Clarendon Hotel in Oxford.

He ended his letter by inviting Iris to continue sharing confidences: ‘I talk a lot of nonsense when I answer them, but maybe I understand more than I let on.’ He saw that Iris feared that her new bohemianism might cause her to forfeit his friendship, and that she placed a value on his good opinion.

Iris’s news unquestionably disturbed him none the less. A ‘bigoted’ atheist, he went to a service in the Greek Orthodox cathedral in Alexandria to think things through before answering. He soon asked his parents to tear up his will, which mentioned Iris, and an accompanying letter, which may also have done. M. R. D. Foot, to whom, alone of his correspondents, he was willing to sound vulnerable, received from him, dated mid-May, a ‘wildly melancholiac letter’ which so disturbed him that it prompted two letters in reply, urging him not to despair, of the world or himself, until Frank angrily persuaded him that his worst fears about the risk of his self-harming were ‘baseless’. The most likely trigger for Frank’s desolation is this news that Iris was taking lovers. Not merely did the war mean that ‘real life’ was passing Frank by, but he stood in danger of losing the woman he still claimed after four long years of war as his princesse lointaine.

Michael Foot’s worries about Frank cannot have been eased when Iris, after lengthy pursuit, agreed on 9 July to be his first lover, though Michael understandably did not tell Frank, who only learned this unwelcome news in his last weeks in occupied Serbia in 1944. It may have played a part in his reckless decision to enter Bulgaria.

Michael meanwhile was bothered by Iris’s growing fascination with Frank. On 16 September she wrote Frank (but did not send) the love poem ‘For WFT’, mentioned earlier, whose conceit is that when they were physically close in Oxford, she measured their distance; now they are separated he is close to her heart:

Not far from the green garden, folded in

Your room, your story & your arms, I guaged [sic]

With a heart quietly beating the long

Long gulf between us. Summer hung

Its colours on the window, & a song

Swept over us from the gramophone.

Now, in a sad September, gilt with leaves,

I am without you, & as many miles

Of sea and mountain part us, as my thoughts

Could then imagine of our separateness.

[Yet you speak simply & your human voice

Gentle as ever: deleted]

– Yet, listening at last, I have caught

That human echo in your tone that might

Call me to love. Nearer, far nearer to my heart

You lie now, distantly in your grief’s desert than

When all your candid years did homage then.

Small wonder if Michael during the months of his unhappy liaison with Iris sometimes felt himself a stand-in for Frank.

Not that they were her only suitors. On 21 July Frank wrote home from Tripoli that he had run into Hal Lidderdale, a ‘small, dark-eyed humanist’ working in an anti-aircraft ops room. They caught up with each other’s news, Frank charging himself with ‘shooting a line’ by dint of things implied. Frank and Hal shared a progressive politics, deploring their respective officers’ messes, with their endless card-playing and drinking, anti-Semitism, complacent prayers for a long war of attrition in the USSR, philistine lack of curiosity about the countries where they were stationed and indignation that every old palace in Rome had not yet been obliterated. Frank claimed to find the other ranks more open, inquisitive and sympathetic.

Frank also shared with Hal a love of Iris and his claim ‘not to have thought of her as a body for four years’ was in part clearly chivalrous bluff to diminish her guilt about her love-life. Indeed he wrote that ‘Hal and I are really rivals for Iris, but the fair object of our rivalry is so remote in time and space that that only serves to cement our friendship. At the moment I think Hal’s leading quite comfortably [as] Iris goes to stay with his mother.’

Probably the reason Iris did not visit Bledlow was because Theo did not approve of her bohemianism. Nor did Frank, who criticised Oxford friends then marrying in order to enjoy sexual love rather than for procreation: ‘If I ever marry, I shall have plenty of children,’ Frank announced a trifle priggishly. And though Iris’s news, even so, did not put her out of commission, another girl soon distracted Frank.