With the Partisans: January–June 1944

I did, in the beginning, make the mistake of regarding this war as an interlude, but not now . . . [It] is an integral part of one’s life, perhaps its consummation.

Letter, June 1943

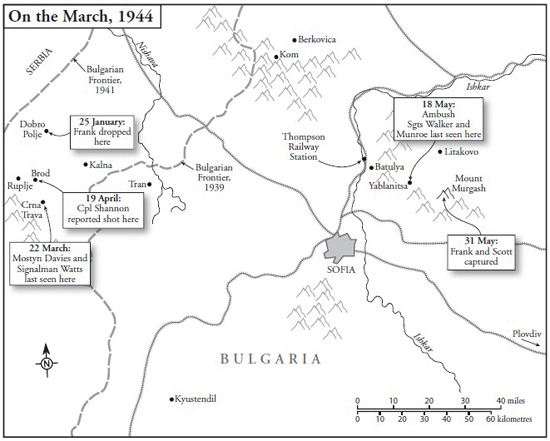

Frank parachuted from a Halifax flying together with three other planes from Brindisi over Dobro Polje in Serbia on the night of 25 January 1944. They had attempted a run one week earlier, when cloud cover had prevented a drop and they had returned to base. That is what the pilot noted; Major Mostyn Llewellyn Davies, who heard the planes, observed clear skies and put down their failure to a signals muddle instead. Confusion marked this enterprise early.

Frank, wearing a knee-length leather coat, landed together with Gunner/Signalman R. G. Watts and fifty-six containers with a total net weight of 4,235 pounds, including 108 grenades, 840 pounds of explosive, two W/T sets,88 a generator, twenty-six machine guns with 11,000 rounds of ammunition, and rations, dry food, boots, socks and clothing. It was bitterly cold. His revolver cocked, Frank gave the parole ‘Bulgarian Partisans?’ and was answered in English ‘Yes.’ One appealing story tells of Frank – much taller than most Partisans and pleased to be safely grounded – picking up a short informant and swinging him around as you might a child. He and Davies now met.

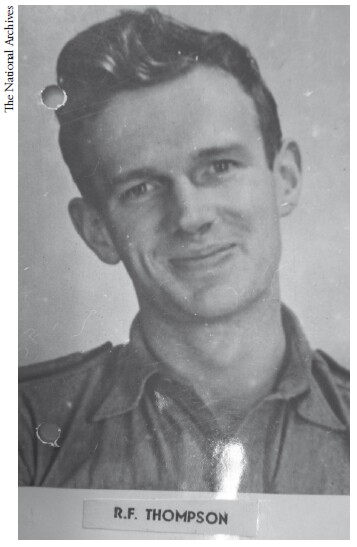

Major Mostyn Davies, c. 1942.

Davies was a brave, determined and resourceful ex-civil servant who, together with his new wife Brenda, née Woodbridge, was recruited into SOE in 1942, a man of exceptional charm, talent and potential. He worked at first in west Africa, later in South America; his present assignment was to make contact with the Bulgarian Partisans, about whom SOE knew very little and wanted to learn more. In pursuit of this aim he had been dropped the previous September in Albania and travelled through many hazards across former Yugoslavia towards the Bulgarian border, supported by Sergeant John Walker (an explosives expert), Sergeant Nick Munroe, aka Muvrin (a Canadian-Croat interpreter), and Corporal James Shannon (a wireless transmitter operator). Davies’s numerous adventures included losing a horse and a mule over a precipice, eating mule, living and sleeping rough, using sulphonamide drugs successfully on a frostbitten Partisan, and trying to assuage fierce fighting between Serb Partisans and what Davies – with interesting carelessness – terms Albanian ‘Chetniks’, after which he travelled with a party made up of both these murderously hostile elements, whom he successfully exhorted to cooperate against their common enemy, the Germans – a proceeding demonstrating his remarkable mettle.

British liaison officers or BLOs were instructed to obtain as much information as possible on the political situation and maintain contact with Partisans without entering into ‘heavy commitments’. In return the BLO was expected to solicit from SOE drops or sorties consisting of arms, clothing, medicines, food and (sometimes) mail from home. Without such supplies, in hostile territory, the Partisans could not always survive, let alone fight. Davies’s greatest headache was an absence of sorties, and hence of food and arms, so Frank’s arrival together with such supplies was doubly welcome. But thereafter there were few drops. A mission without sorties was a liability to all Partisans, imposing on them an obligation of protection in a dangerous area, while the three pack-horses necessary for carrying the BLOs’ heavy radio, accumulators and charging engine slowed them down, restricting their mobility. So the Partisans accused Davies of eliciting sensitive political information while providing little in return.89 And absence of sorties meant that the Partisans went hungry, were poorly armed and were increasingly vulnerable as they awaited drops at pinpoints until late at night, one day after another, shivering in the snow while exposed to the growing risk of enemy action. Mistrust abounded and tempers frayed.

Flying sorties was scarcely an exact science. The commonest reason for the failure of a plane to get through was lack of gaps in the cloud-cover: the pilots’ shorthand for this condition on their so-called manifests (reports) was ‘Met’ for ‘meteorological’. Other reasons included engine failure, the reception party unable to light, even when using petrol, the agreed brush flares – including dummy flares to mislead the enemy – or the pilot dropping loads off-course and losing them. On the night of 7 and 8 April Fascist Bulgars lit flares when planes approached, in order to divert them, and gained thirty-two chutes’ worth of supplies for their cunning; another time a sum equivalent to 100,000 US dollars was dropped to the wrong side. Some pinpoints were lost because the mission was attacked by Fascists and its members had to flee in order to save their skins. Frantic memos show how well Cairo understood Davies’s and Frank’s frustration when, as often happened, weather prevented Cairo offering more support – and how much was at stake.

Neither the numerous and relatively more experienced Serbian Partisans nor the far fewer Bulgarians understood this. Flying was a new technology, in which the simple-minded had excessive faith; Frank himself had flown for the first time only the previous August. They observed that the Allies could bomb Sofia when they did not make drops in Serbia, and so blamed failure of sorties not on rational causes but on capitalist conspiracy or sabotage.90 Every Bulgarian account details the increase in drops after Frank’s arrival – when the weather changed – and ascribes this to Frank himself, while Mostyn Davies is described as prevaricating or slandered as welcoming parachute drops only because they brought his favourite foods. One ludicrous account claimed that most of the cargo (generally in excess of two tons) was delivered for the personal needs of the British.

Such theories remind us that Balkan Communists (Bulgarian or Serb) and BLOs were not natural allies. Serb Partisans commonly refused the sovereigns carried by BLOs in case gold was seen as buying their loyalty; forty-two gold sovereigns were found on Frank when he was captured. When Davies praised one Partisan called Ivan (who was killed crossing the frontier) as exceptional for ‘never once [trying] to lead me up the garden path’, an implication of mutual mistrust is clear. Bulgarian Partisans did not inform Frank that they had their own radio with links to Moscow, which might have been used to contact Cairo.91 Even Frank learned to treat Partisan promises ‘with reserve’.

Bulgarian Partisans themselves warned SOE against dropping agents into Bulgaria itself since its Partisans ‘lead a very mobile and insecure existence and the language difficulty would be very great’. Frank’s mission, called Claridges, was accordingly to remain behind on the Serbian frontier as a rear base while only Mulligatawny, Mostyn Davies’s mission, which Frank came to reinforce, moved into Bulgaria itself. Until that time the two missions were to move and act as one. But the Yugoslav section of SOE was moving to Bari in Italy, while the Bulgarian section stayed in Cairo. Claridges was at first liaising with Cairo via Bari, where the officer in charge of sorties signalled that pressure of work and under-staffing were delaying transmission of signals: ‘No transport. No clerk. No office equipment. No secretary. No hope.’ Meanwhile Frank’s photos in his SOE personal file give him the initials ‘RF’ instead of his correct initials ‘WF’: a tiny omen of the part human carelessness would play in what followed.

During the January that Frank landed, a new repressive organisation, the Bulgarian State Gendarmerie, motorised and with heavy weapons, was created expressly and for the sole purpose of killing Partisans – a token that their nuisance value was real. By 1 July 1944 there would be no living British personnel in Bulgaria not in captivity, and the few BLOs arriving after that date would be ejected by the Russians that September. For both Mulligatawny and Claridges, the scene was set for disaster.

Frank had hesitated for at least forty-eight hours between 22 and 24 December before agreeing to work with the Bulgarian Partisans. SOE’s plans for that country were unclear and might generously be said to represent a gamble. On 24 December – the same day Frank agreed to be dropped – the head of SOE London’s Balkans section Lieutenant-Colonel David Talbot Rice was writing a memo expressing his doubts that it would ever be possible under present circumstances to infiltrate large-scale missions into Bulgaria and predicting accurately that a coup d’état would happen there only after the Russians arrived.

SOE had individual experts for Greece, Yugoslavia and even Albania, but the Bulgarian brief was a mere sub-set of the Yugoslav. In Cairo Frank’s schoolfellow Hugh Seton-Watson – eldest child of the doyen of scholars of Central Europe and co-founder of London University’s School of Slavonic and East European Studies, R. W. Seton-Watson – was best known for his expertise on Yugoslavia, where he had lived. Hugh was strongly anti-Mihailović, and pro-Tito – like the Communist agent James Klugmann, who was second-in-command in Yugoslavia. There was no SOE expert on Bulgaria.

Both Klugmann and the then leftish Seton-Watson probably imagined Bulgarian Partisans as having the same qualities and fighting capacity as Yugoslav Partisans, whose mystical effect on Britons Evelyn Waugh observed at first hand in July 1944 and satirised in his Sword of Honour trilogy. Waugh’s Communist character Major Cattermole, perhaps loosely based on Klugmann, reported women Partisans sleeping chastely with the men, undergoing surgery without anaesthetics and on ideological grounds renouncing menstruation. Time magazine articles show that Waugh only slightly exaggerated: they indeed sang Partisan songs during amputations without anaesthetics, sexual morality was puritanical, and they made a tightly disciplined and hotly idealistic force. Those Frank met in Cairo in December galvanised him too:

In the past few days I have had some profoundly moving experiences. I have had the honour to meet and talk to some of the best people in the world . . . people whom, when the truth is known, Europe will recognise as among the finest and toughest she has ever borne. Meeting them has made me utterly disgusted with some aspects of my present life, reminding me forcibly that all my waking hours should be dedicated to one purpose only . . . no men are more disarming in their gaiety than these . . . who have known more suffering than we can easily imagine.

The case for supporting SOE activity in Yugoslavia (as in Greece) was clear. Tito’s Partisans numbered over 250,000 and were good at killing Germans, while there were between 50,000 and 100,000 ELAS Partisans in Greece – movements so successful that they were, as we have seen, publicly endorsed at the late 1943 Teheran conference, where a Second Front in the Balkans was discussed and rejected. By contrast nobody in SOE London was greatly interested in Bulgaria. So the views of Hugh, expert on Yugoslavia, were questioned by Lieutenant-Colonel Stanley Casson, a London archaeologist brought into SOE in autumn 1943 as an unbiased adviser writing ‘most interesting papers’ on Greece.

Cairo outlined two scenarios. The first ran: undermined by SOE sabotage, the Bulgarian Government surrenders, leaving all its occupied territories and ordering the immediate withdrawal of German troops. But Germany, exactly as it occupied Italy after its surrender in September 1943, and as it would do in Hungary in March 1944, would then invade Bulgaria, vital for German interests and with plenty of quislings. Better, Cairo argued, implement option two: Bulgaria should delay surrendering until Allied troops were close enough to win it over to their side.92

Casson mocked: ‘This document lacks all realism.’ No Balkan state had ever contrived ‘a delayed surrender’, which could only empower the diehards controlling state machinery. Against the Bulgarian Partisans stood the best-organised police service in the Balkans and an officer corps of experience, size and determination, both of which would be liquidated should the Partisans seize power.

Moreover Bulgaria was united mainly in self-preservation. While Yugoslavia and Greece were both occupied by the Germans, and (on the whole) longed to get rid of them, Bulgaria, like the Nazi puppet states of Croatia and Slovakia, was an obedient German ally.

It will be noted that Casson can scarcely be accounted fair or unbiased. Bulgaria was in fact the only country within the Hitler bloc that declined to fight Russia, and was the only one where there was a real Partisan movement. Further, like Denmark, it saved most of its Jews: while non-Bulgarian Jews from the territories it had annexed from Yugoslavia and Greece were rounded up and sent to Poland, the majority of those in Bulgaria proper survived the war. Finally, Casson ignores Serbian aggression against Bulgaria, not least at the battle of Slivnitsa in 1885.

For forty years, Casson accordingly felt, Bulgaria had the single foreign-policy goal of becoming the most powerful Balkan state and dominating its neighbours. That was its motivation both in the disastrous Second Balkan War of 1913, in secretly allying with Germany in 1915 and in refusing to join the Balkan Entente of 1938. The prize was always aggrandisement – seizure from Yugoslavia in 1941 of Macedonia as ‘ethnically Bulgar’, and of Thrace from the Turkish frontier to the River Struma from Greece. Both occupations were notably brutal: ‘most murders were accompanied by torture, most rapes . . . ended with murder’. Germans accounted Bulgarians a simple and only half-civilised ally.

Casson saw no sign of disintegration in a people who could scarcely be war-weary as their 800,000 soldiers had as yet experienced no fighting. Bulgaria’s refusal to make war on its old ally Russia meant that the Soviet Legation stayed open in Sofia throughout. Casson doubted, furthermore, that the Bulgarian Partisans were an organised body imbued with any coherent idea of liberation. He questioned both the efficiency of their organisation and their strength: ‘I think we are staking a lot on a body of rebels about whom we know almost nothing. All we know of them is what they said about themselves to Mostyn Davies.’ He got the impression that – ‘in the usual Balkan way – the Bulgarian Partisans had blown their trumpet long and loud in the ear of the simple Briton’.

The ‘simple Briton’ had his first person-to-person contact with Partisans of the Fatherland Front (or, from its Bulgarian initials, the OF) on 4 January 1944; until then, there was only courier contact. Two men from Sofia, Delcho Simov, a wireless expert (cover-named Gorsho), and Vlado Trichkov (cover-named Ivan), arrived in East Serbia. The latter was a forty-six-year-old metalworker, a Spanish Civil War veteran, and – as he would only much later reveal – political C-in-C of the whole Bulgarian Partisan movement. Although Frank thought Trichkov had a ‘very good brain and a broad European outlook’ it is ominous to learn that he was also famous for ‘bombastic oratory’.

After conferring with these two, Davies signalled Cairo that there were 12,000 Bulgarian Partisans. These had attacked town halls, burning records that might incriminate rebels; had destroyed the machinery in a gold mine in Tran; had attacked a sawmill and a munitions dump elsewhere; and – lacking explosives – had destroyed trains by the simple expedient of removing the tracks. Bulgars had to be, if that were possible, even braver than Serbs; their dissidents in 1923 had been thrown alive into furnaces. But their Partisans were inexperienced and far less numerous.

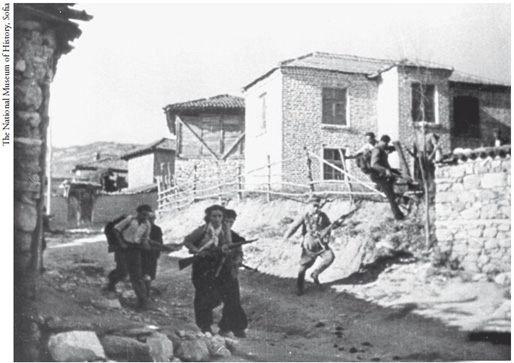

Yordanka Chankova leading an attack to liberate a frontier village, c. 1943.

Some of this sounded encouraging, but Casson was right to think that Davies dangerously overestimated their strength. While he acknowledged that his judgements might need recanting when he got to Cairo that month,93 he feared that ‘we are wasting sorties on them at the moment’. He advocated instead a diplomatic drive, and delaying infiltrating BLOs and missions until the Russians advanced south-west from Romania (which happened only in late August) plus ‘constant bombing’ for six weeks. The differences between Yugoslavia and Bulgaria are clear in their reactions to such Allied bombing: Yugoslavs, while scarcely welcoming the bombing of their towns, understood the point of it in the war of attrition against the Germans; Frank’s captors by contrast took their furious resentment over the bombing of Sofia out on him from the day of his capture.

Calling Davies ‘the simple Briton’ does not seem unjust. Exaggeration of Partisan power by a factor of ten was normal throughout occupied Europe, and Cairo soon gave the probable total number of Bulgarian Partisans as a paltry 2,000 – eleven detachments, each of around twenty men. Even in August 1944, its moment of greatest activity, when there were ‘almost daily attacks upon government offices . . . and upon requisitioned stock’, one source claims that membership of OF reached only 3,600, and the Agrarians who dominated it resented Partisan activity since its major consequence was to bring reprisals on villagers who were often Agrarian sympathisers. The OF, a coalition of democratic opposition forces, excluded right-wing Agrarians or Democrats, since both disapproved of sabotage. So Davies also overestimated their unity of purpose. By March 1944 SOE was wondering whether the fate of Bulgaria was even relevant to the war effort ‘as events were moving so fast’.

The most optimistic guess of 18,000 Fatherland Front sympathisers and/or Partisans coincides with the Russian approach in August. And after Soviets had invaded on 8 September and at once started to impose their own system, executing over 2,000 adherents of the old regime and imprisoning more, the number swelled retrospectively. In this Bulgaria did not differ from every other country suffering enforced regime change, France included.94 One SOE source argued that September 1944 was not even a Partisan revolution, ‘for it is well-established that many of the Partisans first heard of [the Bulgarian coup d’état] from a broadcast the morning after’.

Meanwhile in London the Treasury on 2 March, Casson’s doubts notwithstanding, voted £50,000 towards SOE support for Bulgarian Partisans who, it was gambled, might have ‘a certain nuisance value’ holding down enemy forces. SOE Cairo’s intention had been to have twenty missions in Bulgaria by the end of 1943. There were, apart from Mulligatawny and Claridges, only three other missions, none of which could even enter the country proper: Missions Jampuff, Mizzen and Triatic were stuck in Thrace, and Mostyn Davies was to die in Serbia. Four miles from the border in mid-December, Davies gazed out across Bulgaria’s snow-covered mountains and signalled to Cairo that he found them mysterious.

An SOE narrative put together from Mostyn Davies’s signals covers the first two months of Frank’s time in Serbia. Davies hoped that Frank would help him with his ‘enormous task’ of building a Bulgar Partisan force. ‘Superhuman’ might be more apt.

Shortly after reaching Serbia Davies recorded that ‘The Bulgars had shot seven villagers’ to discourage aid to Partisans. Yet – despite such terror, and despite ambushes and skirmishes – Davies generally sounds upbeat. On the January day that Frank dropped, evidence of the low morale of the Bulgarian Gendarmerie had encouraged Davies: a Gendarmerie detachment asked the Partisans not to attack them, sending welcome cigarettes as a peace offering. One company of Partisans already by 30 December consisted almost entirely of Bulgarian deserters who ‘proved first-rate chaps’. Twenty more deserters arrived on 14 March, with a further forty expected shortly.

That such army deserters might switch sides again if disappointed in the hope of an easier life, Davies overlooks. And about the sufferings he and his men endured towards March – frostbite, hunger, exhaustion, diarrhoea and battle-wounds – his narrative is also silent. As it is also about the mistrust between the British and Partisans.

The Bulgarian Partisans’ dependence on widescale mobilisation causing desertions to their ranks is one factor in making them sound an incoherent and unpredictable force. When Davies proposed that two Bulgarian companies (that is, between 140 and 500 men in all) hold one pinpoint to ensure a drop, Trichkov told him this was impossible without help from Serb Partisans. And when Davies mentions Partisan exploits – for example, the theft of over thirty kilometres of telephone wire to be reused as a Partisan phone line – it is generally Serbs who are praised, not Bulgarians.

Although Serbs and Bulgarians were historical enemies, Communism made both sets of Partisans at least in principle internationalist, and Serbs accordingly assisted the British attempt to arm and develop a Bulgar Partisan force. Frank was impressed by their effort to find common ground vis-à-vis the post-war status of Macedonia, to which both laid claim. On the night of 4 February two planes successfully dropped loads, the explosives being divided into two, one to be cached in Serbia, the other for use in Sofia. Six days were spent organising this, in deep snow, the Partisans succeeding in getting village labour to clear the necessary tracks. Delcho Simov went back to Sofia to arrange transit of some of the contents of the fifty-six containers there; Vlado Trichkov stayed with the mission.

On 10 February they moved five miles south to a new pinpoint (called Clara), and waited. But by 26 February Cairo had regretfully to inform them of the impossibility of flying any more of the sorties allotted them: of the thirty Davies requested that month scarcely any had arrived.

Delcho Simov returned from Sofia on 17 February accompanied by Kamenov, commander of the Sofia zone of the OF, and three days later harassment by Bulgarian Gendarmerie forced them to move. None the less on 4 March Trichkov brought back from Sofia another OF representative, a forty-two-year-old lawyer, Gocho Gopin (code-named Dragan). His journey had taken fifteen days and he was suffering badly from frostbite. Davies explained to him the position vis-à-vis flights. He was to act as liaison person between the Partisans and the mission.

By 8 March, there were still no sorties and relations with Partisans were distinctly strained. Davies was once again accused of extracting information while giving nothing in return. One battalion of Serb Partisans and another of Bulgars were immobilised at pinpoints awaiting drops that never arrived, while the snows now melted fast and the Gendarmerie rallied for a big attack.

During the second week of March, however, their luck seemed to change. Despite shortage of both arms and food they won a battle at Bistrica, where a number of Gendarmerie were killed – possibly eight; and though two Partisans were badly wounded, none died. They were further encouraged by a BBC broadcast on 10 March that took a less anti-Bulgarian tone than before. This may have been in response to Frank’s and Davies’s signalled objections to an earlier hostile broadcast. London now appeared willing to distinguish between the Fascist Bulgarian Government and a population by no means necessarily of the same political complexion. Moreover the same day news reached them of the discovery of a German petrol cache plus the route of seventy trains each of thirty carriages carrying fuel.

By 13 March Kamenov had decided he could ill afford to wait any longer and left for Bulgaria with a detachment of Partisans with whom he hoped to liberate territory around Tran, leaving Dragan to liaise with Davies and Frank. The prospect of having liberated territory within Bulgaria itself was an inviting one. Furthermore, on the night of 14 March, after a wait of around six weeks, two planes at last flew sorties and the following day all supplies were across the frontier. On the 17th another successful sortie increased everyone’s high spirits.

But this run of good luck changed abruptly. On 18 March the missions signalled Cairo that they were surrounded by an enemy force of at least 25,000 – soon thought to be even larger – and would be many days on the run. This was the last message Mostyn Davies sent.

What followed was reported by Frank later, almost certainly over the wireless transmitter set belonging to a third mission. They abandoned their horses, buried their stores and equipment except for one W/T set which was to be carried by a Partisan, and fled by nightfall. On 19 March they reached Ruplje, a party of 200 men hiding in the woods till noon when they were encircled by a mixed force of Chetniks and Bulgars whom they fought off until dusk, Mostyn Davies observing the battle from a nearby hill. The Partisans then waited in intense cold for three hours after which, thinking the enemy gone, they tried to slip away, only to fall into a second ambush. The column scattered in complete disorder, Davies’s haversack being dropped by a fleeing Partisan: the explosives expert Sergeant Walker, though heavily loaded, saved the gold sovereigns with which all BLOs were provided and some maps. Frank requested Cairo more than once for promotion for Walker, whose expert mechanical skill keeping the W/T going the previous year when it badly needed repair had also impressed Davies. Wireless operator Corporal Shannon was never seen again: Frank asked later for his grave, if found, to be marked with the single word ‘SHANNON’.

By dawn the party, now about eighty strong, rested up. They resumed their march on the evening of 21 March when they immediately ran into yet another ambush and, after an exchange of machine-gun fire, scattered into the woods. They decided to split into two groups, Sergeants Walker (the demolitions expert) and Munroe (the interpreter) going off in one direction (they rejoined Frank three days later), Frank, Davies and Signalman Watts in another. They thought it hopeless to try to cross the Morava river without a guide, and turned back on the 22nd to proceed towards Crna Trava, lying low in a village for one day.

Mostyn Davies was by this point exhausted, his feet in dreadful condition; Watts was suffering acute diarrhoea. Around dusk Davies pointed out to Frank that the house in which they were resting was being surrounded by armed men who had crept up unobserved in the gathering gloom. The only possibility of escape lay through a rear window which faced woods across open space some 200 to 300 yards away. Frank left in this way and, though fired on, reached the woods, where he heard further gunfire, what sounded like the forcing of the door and the explosion of a grenade followed by silence. Neither Davies nor Watts was seen again. After watching for five minutes, Frank made his way through the woods and hid for a day or two in the snow until rescued by a kindly peasant, who showed a small Partisan unit how to reach him.

Frank, having tasted the power and malice of the enemy, met up on 24 March with Walker and Munroe at the village of Bistrica eight miles away. Partisan commander Dencho Znepolski believed that Frank had sheltered within a six-foot snowdrift together with Gocho Gopin for two days and nights. He wrote: ‘We found Gopin and Thompson looking weak and exhausted, yet still safe and sound, and in high spirits. Just like little children, they rejoiced at seeing the squad come back from the march with some 230 fighters still alive . . .’ Rumours about Davies’s fate – probably first robbed before being tortured and killed – continued for months.95

Claridges had lost not just Davies but also its radio, and Frank and Gopin now walked thirty miles to meet up with an SOE mission called Entanglement to re-establish communication with Cairo, at Radovnica, which they reached by 12 April and where they stayed three weeks, developing contacts with the Partisans and their General Staff. Frank was now head of both Claridges and Mulligatawny missions and his having survived up to this point saved what remained of both missions. He was, it is worth remembering, twenty-three.

Awaiting them was Claridges’ new signalman Sergeant Kenneth Scott, son of an engineer, born in Forest Hill and educated at Dulwich College, who had dropped there solo on 7 April, in military uniform with rucksack, pistol and brandy flask but without gloves and, above all, without a code-book, which had been dropped separately and in the wrong place. The ensuing drama about the missing code-book and subsequent attempts to get new codes to Frank and Scott absorbed much time and energy. Frank at one point asked Cairo whether they, like him, had a copy of Death Before Honour (a 1939 thriller by J. V. Turner, aka ‘David Hume’), whose opening paragraphs could in that case be used to generate a code for purposes of encryption.

In 2002 Scott remembered Frank as an intellectual who in the evenings would read poetry, in which Scott took little interest, and who otherwise had more sympathetic allegiance to the Partisans than to him, spending time with them improving his Bulgarian. They rarely slept in buildings and one night, camping in the rough with few or no blankets, huddled together in a group to keep warm. Snow was unusual at that time of year but it was still very cold. As Scott was the sole survivor (he died in 2008), his first-hand 1944 narrative is the basis for what follows.

Reports of Bulgar troops approaching from the west caused them to retreat between 1 and 10 May to the Kalna area, where there was a stronger Partisan presence, despite Frank’s wish to stay with the 2nd Bulgar Brigade near Crna Trava, a wish he felt accorded better with his brief. Two days later, on 12 May, Trichkov informed Frank that his Partisans were leaving immediately, via a town called Kom, for central Bulgaria. This sparked off intense discussions lasting for days. Among the most urgent questions was whether Frank and Scott should follow.

Before that, on 21 April, a group of Anglo-American journalists associated with Time magazine happened by on horseback.96 The Partisans eyed enviously these sleek, well-fed men, full of themselves, travelling with saddles and ample baggage, and announcing insouciantly that they were on their way back to Italy via Albania by submarine. But they also offered the missions a chance to write letters home. RAF drops had brought Frank letters dated up to 1 March. One cable from Frank congratulating his parents on their silver wedding arrived on 12 March and another on his mother’s birthday (17 March); he had probably, with his usual care, organised these in advance before leaving from Cairo. A third, praising Bledlow’s success in the Salute the Soldier campaign, he evidently sent via the American journalists that April from Serbia.

Now he was also able to pen his last three surviving letters, which convey a self-contained wisdom unusual in a twenty-three-year-old. To his parents he recalled the Old Testament: ‘“A certain man drew a bow at a venture, missed the venture, but hit the King of Israel.” In the same way this letter is rather a long shot, since mail in this area isn’t very regular. Let’s hope it reaches you.’

These letters, which took months to arrive, are self-effacing, other-centred. This owed, his family shrewdly saw, as much to self-censorship as to military exigency. He responds with his customary careful gallantry to each item of domestic news, to descriptions of wildlife and of Bledlow at war, and to reminiscence of London during the Blitz. He tries to reassure his parents that he would not compete with his cousin Trevor’s MC – despite his own good record in Sicily, to which he alludes. ‘You needn’t fear . . . I’ve got a remarkably clean pair of heels, and now hold the record for the twenty yards sprint for three major battle areas.’

Yet his acquiescence in the idea of the bombing of Rome suggests a new battle-hardened intransigence. ‘How can there be any question when a certain number of old buildings are to be balanced against the whole future of humanity, against man’s chance of ordering his life with dignity or becoming a helot [slave] for ever? . . . what is most precious now is free men’ – that is, not ancient buildings.

Before asking his parents to give his love to friends and relations ‘to whom I should be writing if I weren’t so darned lazy’, he hints at his state of mind. He had been working hard, he hoped to some purpose, ‘keeping brave company – some of the best in the world’. He was enjoying his first European spring for years: violets, cowslips, plum blossom, the shocking loveliness of breaking beech-buds. But England, he reassured them, was the country where ‘they really knew how to organise spring’ and, homesick, he longed to see ‘dog’s tooth violets and red-winged blackbirds again before I go over the hill’. He hopes the food parcels he has arranged from South Africa are OK and is amazed to hear that some lemons had finally arrived: ‘You carefully avoid saying what they were like and no wonder!’ The contrast between these treats and the potatoes and meal-flour soup the Partisans often ate is striking.

Frank’s letter to EP – engaged in the bloody five-month assault on Monte Cassino – anticipates post-war pleasures: co-writing a political book on what the far Left has to offer professionals such as doctors, scientists, engineers, on whose ethics chapter EP is to help; a long walking tour with EP, stopping at many pubs and discussing everything – ‘So keep safe.’ Frank relishes the post-war choice for himself between writing a play, going in for journalism, and returning to Oxford to read History: Slavonic languages interest him less since he ‘already speaks a number’. That might be a hint as to his whereabouts. ‘Keep yourself safe,’ he repeats, adding with rehearsed casualness the second time, ‘it’s important that you should.’ He evidently intuited the risks he and his ‘excellent companions’ might soon take.

These letters, written fifty days before Frank’s death, provide first-hand clues to his morale, and help address his friends’ fears that his subsequent heroism was suicidal. Leo Pliatzky wrote the previous December, ‘I think the sooner you get out of these Ashenden-esque outfits and into some nice steady, stay-at-home job, the better it will be.’ Ashenden: or the British Agent was Somerset Maugham’s 1928 novel about First World War intelligence: Leo feared that Frank at the end of his life was play-acting and so took foolhardy risks. Yet Frank’s concluding remark to EP – ‘Daddy tells me you have been making an ass of yourself about a yellow flower “Some kind of vetch”: don’t do it again!’ – at least suggests their old tone of relaxed family teasing and badinage.

Much of this belongs to the routine anti-heroic rhetoric of that war. His letter to Iris Murdoch written that 21 April, by contrast, is the only one in which he jousts uncomfortably with real intimacy, before fending it off. Since he superscribes this letter ‘Captain WF Thompson’ he evidently never learned that he had been gazetted major.

Irushka!

Sorry I haven’t written for so long. Old Brotoloig97 seems to have been monopolising my attention. I know forgiveness is one of your chief virtues.

Three airmail letter-cards from you, bringing me up to the end of JAN. A great deal of talk about weariness of soul, even among your good friends. You know quite well there’s no danger of your succumbing to it. You have springs within you that will never fail. I want to hear no more of this [illegible] nonsense.

I can’t say precisely what your role in life will be, but I should say it will definitely be a literary-humanistic one. You should continue fooling about. [Illegible] shall be able to compare notes. I shall write a preface to your translation of Levski’s poems & you will bestow the same honour on my life of Vuk Karadzic. We might organise quite a neat little racket. I think we should let Lidderdale in on it with a special brief to deal with Slovenian folk poetry & Pliatzky will be allowed to write Steinbeckian stories about Greek harbour-towns which we shall approve from our Olympian heights as ‘bearing the authentic smell of the Levant’. Foot shall be our chief authority on Turkey. Does this restore your faith in yourself & your ‘mission’? It certainly should.

I can’t think why you are so interested in MORALS. Chiefly a question of the liver & digestive organs I assure you. On one occasion when I had to go without sugar for a month, I felt by the end of it as though I could have won a continence contest against Hippolytus.

My own list of priorities is as follows:

1. People and everything to do with people, their habits, their loves and hates, their arts, their languages. Everything of importance revolves around people.

2. Animals and flowers. These bring me a constant undercurrent of joy. Just now I’m revelling in plum blossom and young lambs and the first leaves on the briar roses. One doesn’t need any more than these. I couldn’t wish for better company.

These are enough for a hundred lifetimes. And yet I must confess to being very fond of food and drink also.

I envy you and Michael in one way. All this time you are doing important things like falling in and out of love – things which broaden and deepen and strengthen the character more surely than anything else. I can honestly say I’ve never been in love. When I pined for you I was too young to know what I was doing – no offence meant. Since then I haven’t lost an hour’s sleep over any of Eve’s daughters. This means I’m growing up lop-sided, an overgrown boy. Ah well, – I shall find time, Cassius, I shall find time.

All the same, I don’t think you should fall for ‘emotional fascists’ – Try to avoid that.

No news about myself. I’m very fit & couldn’t wish for better company.

Lots of love

from Frank

How much should we read into this? By praising the Serbian writer Vuk Karadžić (1787–1864) and the Bulgarian revolutionary Vasil Levski (1837–73) he implies his position, in defiance of military censorship, on the Serbian–Bulgarian border.

Iris Murdoch’s three airmail letter-cards do not survive but evidently they chronicle the progress of her disaster-prone love-life. She found adult sexual passion – one theme of her future novels – bewildering and ungovernable and was therefore seen by some as a bitch or wrecker. She confessed that she had taken Frank’s schoolfriend and rival M. R. D. Foot as a lover the previous summer, before hurting him by bedding and falling obsessively in love with the economist Tommy Balogh – the ‘emotional fascist’ whom she stole from her new flatmate Philippa Bosanquet. Her careless cruelty caused nearly everyone involved (herself, Philippa and Michael) grief about which she is evidently – while starting to think hard about morality – affecting ‘world-weariness’, a stage on the journey to remorse. A whimsical list of literary tasks Frank allotted post-war to Lidderdale, Pliatzky, Foot and himself is also – quite inadvertently – a list of four of her suitors.

Frank’s injunction to Iris to avoid falling for ‘emotional fascists’ like Balogh is telling. Balogh was the first of a series of unresponsive bullies to whom Murdoch found herself masochistically drawn. Balogh preceded David Hicks, then in Cairo, to whom she was briefly engaged in 1945; the writer Elias Canetti followed in 1952–6. If this phrase (‘emotional fascist’) was Murdoch’s own coinage, Frank advises a characteristically wise restraint.

In response to Iris Murdoch’s renewed fear that she was causing Frank pain, he reassures her that he had never loved her, had been too young even to understand the meaning of the word when he had been supplicant and she held the power. Now their roles are reversed.

But to say he had never loved her is partly disingenuous. Precisely one year earlier, the previous April, he had reassured her about her loss of virginity, disclaiming jealousy (‘nearly four years since I thought of you as a body’) and anger (‘no cause’), cautioning her about male misogyny, and sharing his sadness that he had ‘messed up my sex-life . . . by taking physical love far too lightly’ and so missed experiencing mutual sexual love. The element of chivalrous bluff noted in this insistence on his own nonchalance recurs now. His avowal ‘I can honestly say I’ve never been in love’ is partly self-protection and partly an attempt to lessen her guilt.99

Theo in 1948 would comment, ‘I wish Frank had married – had, at least, had some home of his own for his spirit on earth. Iris was not enough.’ Why was Iris Murdoch not enough to make Frank wish to survive? Frank’s 1944 letter suggests one answer.

He refers to two plays. Euripides’ Hippolytus concerns a man who dies after his stepmother tests his chastity: Murdoch in 1946 made her own translation of it. When Frank says he could win a continence contest with Hippolytus, he boasts that he is beyond sexual desire, while acknowledging as a result growing up lop-sided, an overgrown boy. That Hippolytus is vindictively destroyed by the gods for this boast he must have been uncomfortably aware. One important reason Iris Murdoch was ‘not enough’ for Frank’s spirit on earth was that she was, as well as far away, otherwise engaged emotionally and sexually.

He simplifies himself as the down-to-earth soldier-poet whose touching list of earthly joys once more recalls Brooke’s poem ‘The Great Lover’. (Major John Henniker-Major, who met Frank in Serbia at this time, remembered his possessing ‘a childlike intelligence, the innocence of Rupert Brooke, but he was not a baby’.) His list also matches the pared-down pleasures of Partisan life, often on the run, sleeping rough and happy simply to find oneself alive for one more day.

Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar Act V had provided the leitmotiv of his December letter, with Brutus’ ‘If we should meet again, why then we’ll smile.’ He now quotes Brutus from a later scene about finding time, later, to grieve for the death of Cassius, after the battle of Philippi. ‘Friends I owe more tears / To this dead man than you shall see me pay.’ The ironies of ‘I shall find time, Cassius, I shall find time’ are poignant. Time was now in short supply.

If a code is observable here, it is one that suggests undisclosed emotions: Julius Caesar is much concerned with betrayals of friendship, of which Iris too had arguably been guilty by taking Michael as a lover in place of Frank himself. Frank’s praise for Iris and Michael for doing ‘important things like falling in and out of love’, which, he argues, broaden and deepen and strengthen the character, is generous to a fault and probably sincere,100 though by the time his letter together with rumours of his death arrived, such lines must have packed a retrospective sting.

If these developments in London felt to Frank remote, that emotional distance was one that had to be achieved and was not a simple given. One Partisan called Kiril Plashev years later remembered Frank standing stock-still by a village wall, reading a letter from home, utterly absorbed and lost in his own private thoughts.

Some have compared Frank’s entry into Bulgaria to T. E. Lawrence’s exploits, implying that he disobeyed Cairo’s orders, or showed suicidal recklessness – in one account even threatening Kenneth Scott with a pistol to get him to cross the border. But this move, however foolhardy, was deliberated over some weeks. As early as late January Mostyn Davies signalled that he had refused a request for Frank’s assistance to Partisans elsewhere in Serbia since ‘events in Bulgaria’ might necessitate his presence there. And Cairo agreed.

On 22 April Frank radioed that Serb and Bulgarian Partisans were discussing a joint offensive within a fortnight to create liberated territory within Bulgaria around Kyustendil. There was no free territory anywhere inside Bulgaria, but Frank believed the population in areas such as Sredna Gora and Tran – which Kamenov had set out five weeks earlier to help free – to be ‘pro-Partisan’. Although the OF had promised that Frank ‘would be inside Bulgaria within three weeks’, he had ‘now learnt to treat with reserve all such messages’. While he had learned to measure the distance between bombast and accuracy, a development whereby he might enter Bulgaria was clearly being discussed.

Frank was as yet unconvinced of its wisdom. On 29 April he warned that Bulgarians were so demoralised after twenty years of Fascism that ‘1) No repeat No large scale revolt by Army and People against Germans can be expected. General collapse on Italian lines most to be hoped for, with harassing actions by OF supporters. Workers’ revolts in Varna, Sofia, Plovdiv also possible. And 2) The Bulgarian Partisan movement though it has wide popular support is too badly armed and scattered to be made into serious nation wide force before Big Day.’101 Frank advised the continuing bombing of military targets, and the reinforcement with arms of Partisan units, to the south and west of Sofia and near Plovdiv and Botevgrad. And he requested from Cairo ‘general direction soonest’. There is no evidence that he received an answer.

Yet, after the first week of May, a change of heart is apparent. A Major Saunders from Entanglement reported ‘Met Thompson on gallop. He going Bulgaria.’ Frank was ‘galloping’ for fifteen days to evade capture: 40,000 Bulgarian troops with some German detachments and an HQ in central Serbia, supported by aircraft and artillery, had recently been dedicated to the single task of hunting down Partisans, with rewards for each one caught dead or alive, and for each house burned down. With flippant good humour Frank signalled on 3 May, ‘We are being chased by Bulgars . . . pinpoint closed. Cheerio.’ And then Frank and Major Dugmore in Entanglement sent a joint signal on 5 May: ‘imperative have arms and food soonest for this joint force’ – they were travelling with 1,000 hungry and unarmed men. Dugmore was a gentle, sage, courageous South African, with judgement and generosity of spirit, who had been in contact with the Bulgarians before Davies.

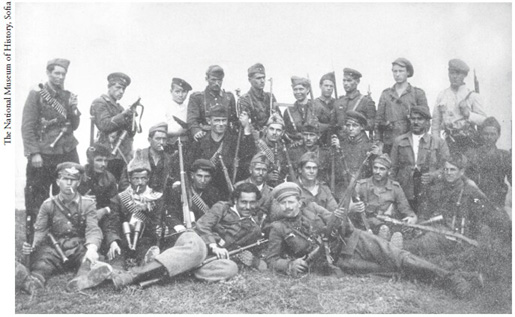

Dugmore, however, had suffered so badly from the winter that Major Henniker-Major was flown out to replace him. The latter wrote that Frank was desperately tired and dispirited both by Davies’s death and by lack of encouragement or direction from Cairo. Henniker-Major, who liked Bulgarians and thought they made reliable soldiers, none the less judged these Partisans an inexperienced and low-level mix of individual deserters and Communist civilians from the towns with the ‘unreal and slightly horror-comic air of a brigand army, boastful, mercurial and with an inexperienced yen to go it alone’. Frank had constantly to fight both to avoid being taken over by the well-organised Yugoslav Partisans and also to avoid being led off on a lunatic expedition by the Bulgars, who insisted they were now going to Bulgaria where they could persuade the people to rise and set up resistance areas.

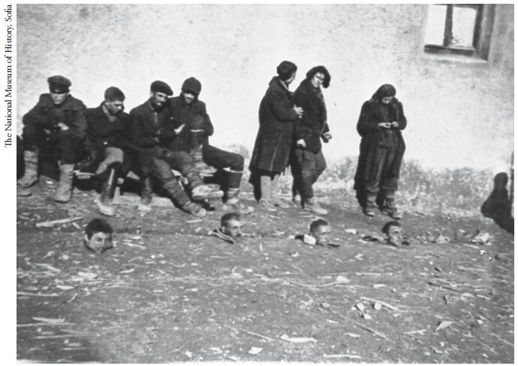

The Hristo Botev Partisan brigade, 1944, at Sredna Gora.

Frank was so exhausted that on one march he fell over a cliff into a river; and all of Henniker-Major’s party fell asleep. The wireless, too, received a dousing, from which it did not recover. Henniker-Major none the less reported Frank full of hope. On the nights of 10 and 11 May twenty successful sorties were flown, and the air was full of containers, divided half to the Serbian and half to the Bulgarian Partisans. Frank signalled, ‘This is the biggest encouragement Bulgarians have had since Mostyn arrived . . . after last night and a few more like it, stream [of recruits] may become torrent.’ Yet Frank continued to argue against the dropping of further British agents: ‘We have eight Englishmen here now, which is thought maximum handicap for any Partisan unit entering spring gallop.’

A two-day council of war followed, probably near Kalna, where a well-known Montenegrin Partisan judged the organisation of Bulgarian Partisans incredibly bad and strongly advised Frank to stay in Yugoslavia.102 Dugmore too thought the Bulgarians so reckless and unreliable that he went so far as to ask Henniker to disavow the OF to SOE Cairo. But theirs was not the only counsel.

Georgi Dimitrov, leader of the Bulgarian CP waiting in exile in the USSR, from Moscow was urging the Bulgarians to enter their own country to stimulate revolt in the cities. This was both doctrinaire and crazy: the Serb Partisans’ success stemmed from their operating brilliant hit-and-run guerrilla raids from the hills, and carefully avoiding towns. But around 10 May the Bulgarian Politburo – also in Moscow – ordered the 2nd Brigade to leave at once for the second largest city, Plovdiv, to help stimulate national revolt there. And Cairo in its last surviving directive – 25 April – had instructed that ‘Thompson should remain longest possible with OF delegates . . .’103 This instruction to remain with the Bulgarian Partisans helped shape Frank’s fate.

He was none the less doubtful. Scott felt that Frank did not want to go into Bulgaria, but the Bulgarians insisted they knew their own country and were going anyway and at once. Frank had no time to secure Cairo’s confirmation and his ‘impatience of delays’ may have played its part in what followed. Henniker observed that Frank, fearing it might appear that the British were afraid to share the risks their friends took, reluctantly and with misgivings thought that it was his duty to go. He felt disillusioned with the failure of support from Cairo, and the Partisans pressed him to accompany them. While fully realising the folly of going into Bulgaria, and the negligible chances of survival there, Frank decided to take the gamble.

The expectations of receiving further large shipments of British weapons by air were so exaggerated in certain people’s minds that they assumed unrealistic proportions. And Frank similarly hypothesised that, if the mission went across, this might trigger a new atmosphere in which ‘a mass-uprising would take place’. Exactly such a new atmosphere, after all, had that April come about within southern Serbia itself. On 16 May Claridges requested blind drops for five pinpoints to supply five different detachments or odredi within Bulgaria, whither they were setting out the next day. It was the final signal from them that Cairo received.

The following day, Wednesday 17 May, Frank and Scott, accompanied by around 180 Partisans, entered Bulgaria. Their mission included Gocho Gopin, liaison delegate between Claridges and the Bulgar Partisans, Vlado Trichkov (political leader) and Dencho Znepolski (military leader). Trichkov, waving a tommy gun, made a grandiloquent speech declaring himself Partisan C-in-C and they crossed into Bulgaria ‘as if it were a Sunday school outing’. They hoped to join up with remnants of the Chavdar Brigade, which had been effectively wiped out a fortnight before, but the guides sent to tell them had all been killed too. They had some English boots and uniforms which had ‘gone to their heads’, some arms, no compasses, and for maps only Frank’s and Scott’s silken map of the Balkans. They crossed in a state of euphoria in full daylight, under vigilant enemy air reconnaissance, without guides and off-course.

Second Sofia brigade on their ‘long march’, May 1944. Frank third from right.

Scott’s narrative describes the first ambush soon after crossing, by twenty Bulgarian Gendarmerie armed with knives. One Partisan was killed, Dencho received three stab wounds, and a policeman was taken prisoner who, in order to gain lenient treatment, claimed to be a married recent conscript with children. When his papers showed that he was both single and a member of the regular forces, his head was smashed in with a rifle butt.

Despite constant police patrols they crossed the Iskar river in daylight and captured an ardent Fascist whom they forced, hands bound, to guide them for two days; probably the Partisans shot him later during a skirmish. Wrongly believing that they were in Partisan territory, they stopped in Lakatnik to rest for some days and buy food for the march. But after less than an hour reports arrived of an approaching Gendarmerie patrol by whom they were harassed until dusk; and they were soon further beleaguered by Bulgarian troops approaching with mortars whom, forewarned by scouts, they managed to bypass. Their march was quickly turning into little more than a succession of disorderly routs.

They were now travelling short of food, in unfamiliar and hostile territory, where – it was becoming apparent – they constantly risked betrayal to the Gendarmerie or army. Keeping to the mountain heights offered some security, though the army was also establishing hilltop posts throughout the area: such garrisons fired a single shot to signal the sighting of Partisans, which acted as a useful warning to the Partisans themselves. A much-needed rest in a wood on 18 May was interrupted by machine-gun fire at noon; encircled, they scattered, splitting into two groups. Frank fled with Scott, around twelve Partisan officers and five or six other ranks including three women. Although Frank was struck in the back by a bullet while making a getaway, this fortunately lodged – scholar-soldier that he was – in the dictionary he carried in his haversack, saving his life.

From the safety of the far river bank Frank and Scott were dismayed to see a Bulgarian Gendarmerie party leading their mules away still loaded with supplies. They were squatting on an unstable gravel slope, the sound of which when one Partisan slipped alerted a Bulgar policeman: well-aimed machine-gun fire soon followed. Search for a new hide-out was delayed by Trichkov having been shot in the ankle, by a new party of Bulgar troops proceeding northwards, and by their own exhaustion and hunger. They slept the night in thickets on a hilltop; their only food had been a small quantity of cheese captured not long after entering Bulgaria when they destroyed a factory that villagers told them provided cheese for Germans.

After buying provisions they resumed their march eastwards around 25 May, redistributing their few remaining weapons and intending to join up with the Murgash Partisans.

But Frank and Scott (by this stage with a compass, and near a village called Batulya) decided they had travelled too far south and discussed returning to the Yugoslav border, a route they now knew. Trichkov’s ankle wound was not healing and slowed them down to three miles a day over rough country. They had been ambushed each day and the Partisans had had no military leader of their own since 18 May. They claimed they had no wireless communication. Frank had lost confidence in the remaining Partisans with whom they were travelling.

Frank and Scott therefore agreed, when opportunity presented during the next skirmish, to split from their group and hide in the forest. After lying low until it was safe, they would continue at greater speed towards Sredna Gora, where they hoped to join up with another Partisan group headed for Sofia/Plovdiv and re-establish contact with Cairo. This decision makes sense of Frank’s half-jokey remark reported by Scott that September: ‘These Partisans are no good: maybe we should find some better ones.’

Three Partisans were soon detected at the skyline trying to run away; one was detained and brought back to the main body. A meeting was called at which orders originating with Trichkov were read out by his deputy, to the effect that deserters would be shot, as would those discovered eating clandestine supplies.

On 30 May the Partisans debated their plight while in an orchard eating cherries so unripe they had no stones; Frank and Scott attempted to eat leaves with salt and then divided a live wood-snail, Scott eating the tail, Frank the head. After this, for two hours, they fell silent. They now had lice – enemy number two, they joked. So desperate were they that three Partisans were detailed to acquire food in the local village, despite its being occupied by an army unit. They returned with fresh bread which was divided between everyone with great care, Frank and Scott using their hats to avoid losing any crumbs. Then, exhausted, they slept in the orchard and surrounding woods.

After a Gendarmerie patrol was spotted at dawn 300 yards away, they decided not to move further. But at 14.00 a patrol of twenty men approached from the village where their presence had evidently been betrayed – possibly by a deserting sentry promised amnesty or by guides offered bribes104 – and two hours later fired the first bullets into the wood. Frank and Scott, as they had planned, split from the group, moving uphill while the Partisans were fleeing down and hid between four trees in ground cover of dead leaves and branches.

They could hear small-arms and mortar fire, and the excited shouts of Anna, one of three women Partisans who had stayed with the group and who, despite her painful shrapnel wounds, killed several Bulgar troops with grenades. The copse in which they were hiding was approached from both north and east by troops who, from ten feet away, spotted Frank and Scott, shot at them and then captured them.

Four soldiers dragged and brutally kicked them while those soldiers who could get close enough, the escort of four included, struck them with fists, pistols and rifle butts until an NCO arrived. Both had their hands tied behind their backs, Frank with a belt, Scott, whose hand was poisoned and swollen, with a rope, the bonds stopping circulation, cutting almost to the bone. In the village where the bread had been bought peasants turned out to swear, spit and strike them with fists and any heavy articles they could seize. The recent bombing of Sofia, which Frank had encouraged, played its part – they realised – in this hostility: some accounts report Sofia 25 per cent destroyed, with thousands killed. Frank, extremely weak from lack of food, the march and ill-treatment, lost his balance and collapsed.

After preliminary questioning to ascertain that they were the British fighting with the Partisans, they were taken to a cellar where a well-dressed civilian beat them with a thirty-inch truncheon with a hard core, while soldiers, policemen and other civilians crowded in the doorway to watch. Orthodox interrogation by a commanding officer who had extracted information about the mission and its history from a captured Partisan followed; he promised them that, as uniformed members of HM Forces, they would – as Frank requested – be treated as prisoners of war. Frank was shocked that his captors seemed to know every fact about his activities and movements. His and Scott’s possessions were set out on a table, and a Bulgarian lance-corporal who knew some English eked out Frank’s ‘scanty’ knowledge of Bulgarian.

They were soon taken to a school at Litakovo near Sofia where they shared a room with the two Partisans who had deserted on 30 May, the three villagers who had sold them bread, and another Partisan, all handcuffed. At each stage there were further beatings, spitting and kicking in front of an audience of soldiers, Gendarmerie and citizenry, a stream of sightseers rendering sleep impossible. The screams of two women Partisans who had been captured too, Anna and probably Yordanka, continued through the night, accompanied by sounds of heavy furniture being thrown around: they were never seen again. Some of the men were decapitated. Frank was taken for three hours of interrogation at around three in the morning and returned haggard, scarcely able to stand; Scott followed. Then there was a more military and clearcut interrogation, in front of two W/T sets, only one of them recognisable to Scott: he wondered – accurately – whether the second set had been taken into Bulgaria unknown to them. Many questions concerned the SOE signals school in the Middle East, the exact station to which Scott had signalled, and the whereabouts of other British missions in the Balkans. These questioners were formidably well informed.

On 1 June Scott’s request for medical attention to his injured hand was granted, the doctor especially interested in discovering where Frank had learned Bulgarian; it is one of many horrible ironies that his meagre knowledge of the language probably helped to incriminate him as a ‘spy’. During the following twenty-four hours sightseers (and Scott’s poisoned arm) rendered sleep impossible; and on 2 June Scott was taken off into individual imprisonment in Sofia. He was needed to operate his wireless set in an attempt to acquire information from Cairo’s replies useful to his captors.

He never saw Frank again and was told around 11 June that Frank had been shot. ‘C’est la guerre,’ his messenger shrugged, when asked why. He was also told that Frank had died bravely. No details were vouchsafed; and an authoritative account of Frank’s death was not published until 2001, in Kiril Yanev’s The Man from the Legend, a narrative to which we return in Chapter 14.

On 9 September, after fourteen weeks’ captivity, Scott was released and made his slow way back, via Istanbul and Cairo, to London.