Conversing with the Dead: 1944–7

‘Who killed Cock Robin?’

‘I,’ said the Sparrow,

‘With my bow and arrow,

‘I killed Cock Robin.’

‘Who saw him die?’

‘I,’ said the Fly,

‘With my little eye,

‘I saw him die.’

Traditional

The month Frank died EP pondered the cruelties of war. Serving with the smart 17th/21st Lancers (motto: ‘Death or Glory’) he had taken part in the prolonged battle for Monte Cassino, which fell on 18 May 1944, followed on 4 June by Rome. The Allied advance up Italy unwisely advocated by Churchill (via Europe’s falsely named ‘soft underbelly’) was vexed by mountainous terrain, by Allied supply lines stretching ever longer, by the withdrawal of troops to fight in Normandy, and by ferocious German resistance. Each day incessant shelling and mines caused new casualties. In the week that Frank died, EP was engaged in the battle for Perugia, and his squadron of fifteen tanks had been depleted to a mere five, of which he commanded two. EP survived a shell splinter denting his tin helmet and instructed his sergeant in a Sherman tank to lead the advance into the city while knowing the risks attendant on being in the lead tank, which was often knocked out by enemy shells. Indeed the driver, co-driver and wireless operator were all killed.

To make sure, a German soldier threw a hand grenade into the turret, looked inside and poured petrol in before setting the tank on fire. EP next day found a pile of ashes in the driver’s seat, moulding the shape of the lower half of a man. Conceivably on the grounds that this had made identification of the bodies harder, the army elected to send each next-of-kin Missing Believed Killed messages, in this way extending a false hope of possible survival. As each new hope is disallowed, grief is revivified – a cruel protraction, EP recorded, of the anguish of bereavement. Though this is EP writing forty years later, even in 1944 the cruelty of this message was clear to him. And, at just twenty years of age, it was he who had to answer the piteous, self-effacing letters of relatives:

My brother was all I had in the world . . . and I would like to know a few more details, if the spot where he was buried is marked or did the explosion make this impossible . . . Please did one of his friends pick some wild flowers and place on his grave?

If you really could get me a photo of his grave it would set his wife’s mind at rest as she is greatly grieved . . .

EP’s own reaction to stress was, since childhood, a bout of impetigo. He did what he could to offer comfort and abbreviate the grief of enquirers by giving the deaths a definite term; he of course did not tell them that, in the causal sequence of command, it was he who had directed them towards these deaths.

The news that Frank had similarly been declared Missing Believed Killed reached him in October, and sixty-five years later his commanding officer Val ffrench-Blake, who thought EP highly intelligent and sensitive, and enjoyed listening with him to his 78s of Bach’s Double Violin Concerto on the mess’s wind-up gramophone, recalled how ‘cut up’ he had been. EP sailed for home, probably from Venice and on compassionate leave, entrusted with ffrench-Blake’s diary, on 26 May 1945. He spent the sixteen-day voyage co-writing a play about Balkan Partisans, and later that year published his first prose, the story ‘Drava Bridge’ about Partisans in Yugoslavia. Modern warfare was the ultimate negation of individual agency; only the low-technology warfare of Partisans, he believed, could still be termed ‘heroic’. As for his parents, they were about to suffer exactly the hideously protracted bereavement that EP decried.

On 14 June Theo wrote pleasantly to Frank, ‘Does Stalin do his washing-up?’: she would welcome his ideas on this aspect of ‘post-war living’. A wind from the future was blowing strongly now that the Second Front had opened, and she described D-Day in Oxford to Frank. Over the eight o’clock news they had first heard of German forces clashing with landing craft, but only the sight of vast flocks of troop carriers flying north-east home over Wain Hill and past Risborough caused them to understand. In the Cadena coffee shop a Lady Richards confirmed to Theo that ‘It had started’.

Troops awaiting D-Day had been ‘sealed off’ to avoid rumour spreading and maximise surprise to the Germans, thus also increasing surprise at home. Lunching on Banbury Road with Barbara Campbell Thompson, the news started to filter through: 4,000 ships and 12,000 planes had been involved. Theo observed the ‘huge and most unusual’ queues she had ever seen, irregular and restless: donnish men, North Oxford women, charladies, young cigarette-smoking men who might have been Communists or reporters. She wondered whether they were queuing to see some great politician until she understood that all they wanted was newspapers, which were getting snapped up at inflated prices between leaving the van and landing on the pavement. Two round-helmeted American doughboys each with an Evening News offered to get Theo a newspaper. She began to measure the momentousness of the day’s events.

Theo communed with Frank about the courage asked of men: ‘One can hardly bear to think how brave they have been and are being . . . the world will never know all the courage that has been built into the success of this venture.’ Frank, unbeknown to them, had played his small part in the creation of a Balkan distraction, thus tying down troops far away from the Normandy landings.

At fortnightly intervals through the summer of 1944 EJ and Theo received cables signed with Frank’s name: ‘Am safe and well, letter received, parcel received’. On 28 June Theo wrote asking ‘What parcel? We sent nothing but a few Lifes.’ One cable from Frank on 7 July reading ‘Letters received many thanks’, and ending ‘Well and fit’ did EJ ‘immeasurable good’. Although throughout August Theo’s letters to Frank were returned ‘Addressee is reported missing’, the uncanny illusion of his post-mortem existence was unhappily sustained by Frank’s having pre-paid Stuttaford’s in Cape Town to send Bledlow regular foodstuffs: as late as 16 September Theo was thanking Frank for his welcome gifts of crystallised and baked fruit and tinned tongue – ‘the greatest luxury, even in peace-time’.105 A fortnight earlier the slapdash wording of a final cable on 3 September aroused suspicion: ‘Fondest love and kisses’, signed ‘Thompson’. These bogus telegrams caused distress: Theo and EJ wondered whether Frank had been captured and the cables maliciously sent by the Germans.

In fact these messages were a form of well-meaning subterfuge, sent by hard-pressed cipherines in Bari instructed to keep up the morale of British missions and their families.106 BLOs dropped into hostile territory, cut off from normal communication, often had time on their hands to worry about personal affairs. To mitigate the difficulties of letter-writing, fortnightly telegrams purporting to come from the man himself were sent from Italy to relatives at home. These EFM or Expeditionary Force Messages used numbers denoting a phrase of which at any one time three might be combined: a statement of health, acknowledgement of receipt of letters, and a greeting. SOE recommended that these cables ‘should never be sent after wireless touch with the mission concerned has been interrupted’. This was a lesson learned the hard way, and by December 1944 Thompson family agitation brought the ‘appalling practice’ to a halt.

Meanwhile Theo and EJ were also grappling with the fact that EJ had stomach cancer – sometimes referred to by Theo as his ‘ulcer’. Theo tried to conceal the true facts of his illness from her sons, until 19 August when the doctors gave EJ up as inoperable and incurable and she petitioned for compassionate leave for both boys. Her cable to Frank’s commanding officer received no reply: ‘we feel that Force 133 is rather indifferent to families of its men’, she commented. Theo then approached a friendly brigadier who advised that unfortunately Frank was ‘in an area where it was very difficult to communicate with him’. By then EJ had started responding to X-ray treatment and on 7 September they cabled again, suggesting that Frank after all postpone taking leave since ‘If Frank were in the Balkans, say Jugoslavia, as we imagined him to be, he would (with the Russians sweeping through as they seemed likely to . . .) hate to be snatched out of it.’ Despite the absence of proper letters, they still hoped that he would turn up ‘when that part of the war ends’.

Theo accordingly had Frank’s room cleaned and his piano reconditioned at considerable expense and gave detailed thought to Frank’s post-war life: ‘Daddy says you must use your first ½ year writing your book. Then, in October, New College.’ When EJ’s condition worsened she cabled a third time, which accelerated the arrival of Frank’s Missing Believed Killed telegram on 21 September. To compound their sufferings, this was according to one source soon followed by a macabre, unnerving cable thanking Theo for her letter and sending his love.

Bureaucratic ineptitude apart, the reasons for this delayed notification were not sinister. Scott in captivity in June attempted to alert Cairo by inserting girls’ names into his messages – Cecily, Anne, Phyllis and so on – to spell ‘captured’. After the Gestapo stopped this, his messages arrived full of other deliberate errors which – as one of SOE’s best signals operators – could not be accidental. Cairo accurately concluded that he and Frank had been captured and Scott was operating under duress; they hoped Frank might have escaped and be making his way towards a neighbouring mission.

Cairo knew that it was a matter of life and death that they give no hint to the Gestapo, or Scott would quickly have been murdered: he was safe only so long as the Germans were convinced that Cairo was fooled. A tense game of double bluff ensued, Scott repeatedly requesting sorties so that his captors could score easy successes by shooting down Allied planes. SOE Cairo had to think up every possible plausible excuse for not sending sorties, to delay the Gestapo’s suspecting anything amiss. Everyone concerned passed three anxious months.

For analogous reasons Frank, even after rumours of his fate began to circulate, could not be declared Missing Believed Killed until after the Bulgarian collapse on 9 September when Scott suddenly found himself released into Sofia: the Germans scrutinised every such notification, which once again would have endangered Scott. Moreover it was Scott alone who might be able to provide the circumstantial evidence on which the case for Frank’s probable demise could be based, and which therefore had to await his debrief in Cairo.

This was how SOE saw it. To EJ and Theo it seemed that the authorities obstructed all their attempts to uncover the truth. Lieutenant-Colonel David Talbot Rice, Head of SOE for the Balkans and Middle East, nevertheless set up an interview with his deputy Major E. C. Last, who ‘looks after the country in which your son was operating’. This took place on the afternoon of 1 November 1944. Room 238 in the Hotel Victoria on Northumberland Avenue was, as in good spy fiction, secretly dedicated to SOE use. Major Last found the interview ‘rather difficult’ and its aftermath worse. Neither Thompson had at this point ever heard of SOE and did not understand that what they were told was ‘in confidence’. They wondered whether SOE stood for Subversive Activity in Occupied Enemy Territory.

EJ organised the flurry of Bledlow initiatives that immediately followed. He placed on 4 November in The Times a Missing notice, requesting that any information should be sent to the parents; the News Chronicle on 15 November carried a half-page article, ‘BRITISH OFFICER LED BULGARIAN PARTISANS: NAZIS MURDER MAN ON SPECIAL MISSION’, describing Frank’s leading ‘one of the most hopeless and dangerous enterprises of the war’. Then, after an Evening News journalist had been shown Frank’s room in Bledlow, the paper brought out on 20 November an article mentioning EJ and Theo’s wish to publish a memorial volume. Finally a short notice in the Daily Telegraph on 28 November announced that EJ sought news of his son.

Major Last was affronted and disturbed that details compassionately vouchsafed should so quickly enter the public domain, offering comfort and intelligence to the enemy and ‘endangering other BLOs in the field’. EJ, who knew Bulgaria had been ‘liberated’ – it had indeed no more Germans (or for that matter SOE agents) active anywhere – was unimpressed by Last’s complaints, and continued campaigning. So Theo told EP’s friend Arnold Rattenbury, ‘I’ll look after Bobby Vansittart and the Foreign Office; you look after Harry Pollitt [of the CPGB] and the Comintern.’ And EJ duly wrote to his friend Lord Vansittart, then out of office, requesting an investigation into the circumstances of Frank’s death and on 10 November to Churchill requesting prosecution of the Bulgarian war criminals. Both letters were forwarded to the War Office. Theo also got her sister Marie-Jo in the USA to request information on Frank’s death, via the State Department, from the British Embassy in Washington DC.

In response SOE planned to send personnel to Sofia to help the Allied Control Commission (ACC) investigate Frank’s murder. When the Foreign Office at first refused permission, Major Last feared a ‘violent reaction’ from the Thompsons, who failed to see that, since the ACC was now the official ruler of Bulgaria, its negotiation of the terms of the Armistice took priority. They also understandably exaggerated Frank’s importance – one only out of seventeen missing Britons in Bulgaria, ten of them pilots – and also ignored the fact that every SOE officer about to be dropped into enemy territory knew that his chances of trouble if captured were very high. ‘It was part of one’s routine training.’

While Theo was admirably level-headed, EJ had a tendency to ‘fly off the handle’, ungovernable and impenitent. He boasted to SOE of having consulted five different newspaper editors, and threatened that he could also have ‘Questions asked in the House’. One year later he did so. EJ feared the dominance of those for whom secrecy – taking cover under so-called ‘security considerations’ – was becoming a mania, one he rudely labelled crypto-Fascist and thought far worse during the present war than during its predecessor. An efficient Thompson family campaign against the British establishment was picking up speed, outlasting EJ’s death in April 1946 and continuing, under EP, a further half-century.

The Thompson family were not alone in their uncertainty about whether Frank was alive or dead. On Sunday 3 December 1944 Rachel Annand Taylor wrote, in a weirdly curlicued hand, from her Bloomsbury flat the first fan letter of her long life. ‘Dear Mr Frank Thompson, Please pardon my intrusion . . . if I do not inscribe my note instantly I shall lose courage and forbear,’ she began, affecting a note of shy girlish distress. A seventy-year-old Scottish poet admired by D. H. Lawrence and by the severe Richard Aldington, her discovery of Frank in the Observer that dreary Sunday afternoon suddenly kindled into delight. Frank’s poem ‘Soliloquy in a Greek Cloister’ evoked a Greek Orthodox priest from St Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai: ‘Lover of Cypresses, a friend of death, / With fierce black beard, weak mouth, a drunkard’s eyes’. It caused her to inhale far-off Byzantium ‘like a whiff of perfume’ and to discover Music, Vision and Strange Imaginative Vibration. What more could one ask? ‘If you have a moment’s leave, will you tell me if you have published a volume? Perhaps I should know. I do try to follow new poetry . . .’

EJ, still piecing together Frank’s story, replied that the true sequence of events was as yet very unclear. After June they had received no letters and the family had – like Rachel Taylor – been writing to a phantom, and receiving cables from the dead Frank in reply. Frank’s younger brother fighting with his regiment in Italy joked quite unintentionally, ‘Do write soon: you are becoming quite a ghost-voice.’ It was EJ himself who had submitted Frank’s poem for publication in the Observer.

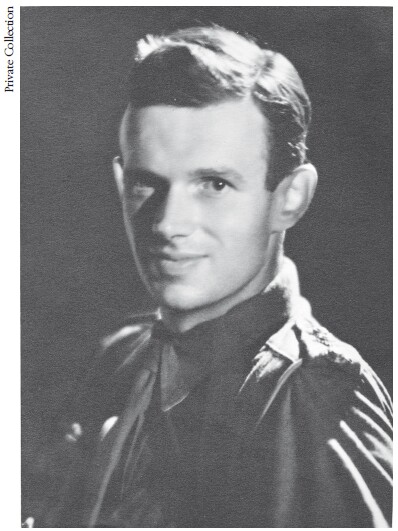

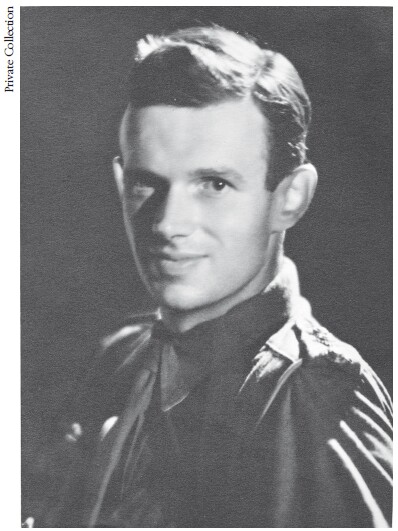

Rachel Taylor replied to EJ with a sentimental fluency. ‘So the poet who suddenly seized my attention was indeed “of the golden race” as the Greeks described those who died young in battle; and his life and death were greater poetry than even his verse.’ A photograph EJ had sent her, she felt, conveyed the expression on Frank’s vanishing face with unusual perfection, ‘intellectual force & sweetness of temper & the radiance of the idealist . . . alas, we are in desperate need of such as he . . .’ Yet perhaps it was good, she added, that Frank had been spared the bitter disillusionment of the coming post-war world.

Frank sent Iris a copy of this photograph on which, together with the second half of line 2 of Alcman, Fragment 26, he wrote, ‘To Irushka, whom I miss these long years.’

Rachel Taylor advised his parents to collect fifty poems of quality for publication. Of Frank’s verse his father accurately wrote that ‘His style was more traditional than I fancy he wanted to think, but what does that matter?’ Neither Taylor nor Frank despised lyricism. A selection of Frank’s verse soon went out to editors and fellow poets. Oxford University’s Clarendon Press had just published Edward’s 100 Poems: might they wish to publish his elder son’s as well? The Press took the advice of Gilbert Murray, who cherished a photograph of Frank in his Boars Hill library, and who – by coincidence – was Rachel Taylor’s mentor too.

Murray wrote to OUP that everything about Frank’s gallant and brilliant mind and the real beauty of his character gave special interest to all he wrote; some of this feeling would get through to the general public who did not know him, but not much. ‘As to the poems themselves, they are above the ordinary level of such recent poetry as I know, and some are really beautiful . . . but there is more promise than achievement.’ Frank, had he lived, would have written more and rejected some of these. OUP accordingly wrote to Theo that, although they had, exceptionally, published Edward’s volume, poetry was not really ‘in our Oxford province at all’. The Thompson family should try Faber’s instead.

Others agreed about the provisional and unfinished nature of Frank’s work. One small publisher thought many poems too private, some too academic, and the bulk too young or too near their subject. A commemorative volume might be published, to include some prose pieces and letters. Penguin New Writing editor John Lehmann, noting how interested the Russians were in Frank’s heroic reputation as a martyr in the Partisan cause, wrote from the Hogarth Press to say ‘the poems by themselves don’t make sufficient impression, but they would do, bolstered by letters and prose’.107

Other consoling replies followed. John Arlott, remembered today for thirty-four years of Test Match Special cricket commentaries in his Hampshire burr, but then a policeman-poet and novice broadcaster, had been writing fan letters to Edward about his poetry since 1941. He liked Frank’s immensely too: ‘a poet and a man to my taste’.108 The poet Patric Dickinson, also working for the BBC, agreed. Both admired Frank’s ‘Damascus Road’, duly broadcast the following spring.

Rachel Annand Taylor in a new letter to EJ conveyed well the strange quality of Frank’s life story and verse alike: ‘I have not really said what I feel. It is difficult. You have communicated to me a spiritual experience – of pain illuminated by a kind of elation, the elation that can be caught only from contact with great beauty. And I am profoundly grateful.’ Pain illuminated by elation: grief somehow shot through with joy. Such is the stuff of tragedy. Frank’s story, and his best few poems, shine out with both emotions, as also with his humour.

Soon a hundred more letters of condolence arrived. Few were as stylish as Taylor’s, and style mattered to the Thompsons. An official letter, condemned as ‘Conventional verbiage, sub-adolescent’, read: ‘you will be glad to know that your son was one of those extraordinarily gallant men who volunteered to be parachuted into enemy-occupied territory to attempt to contact the guerillas’.

A feeble yet ‘sweet’ letter from Frank’s first cousin Graham Vivian foolishly suggested that ‘It may console you to know that he was a Major.’ This too was ridiculed: as if mere rank could atone for Frank’s loss. Cousin Graham’s story illuminates Frank’s: a Bailey Bridge expert fighting in Italy, he trod on a mine two weeks later and was killed, four Sikhs bringing his body back through heavy fire. When his brother Trevor visited his regiment, two Sikh soldiers wept and kept a three-day fast in Graham’s memory. Trevor too was killed months later in a flying accident and Graham’s afflicted parents sought solace for this loss of both their sons in séances. One medium impressed them by telling them that Graham had been a secret poet, and on searching his effects they were astonished to find poems in both English and Scots Gaelic – Graham having a Highlands fetish. What the Balkans were to Frank, Scotland was to his first cousin Graham, a focus for passionate romantic aspiration.

‘How mysterious’, Edward mused, ‘even those closest to us are.’ He might countenance his sister Molly’s claim to have spoken during séances both to her nephew Frank and to her own dead sons ‘if those in the afterlife were not always doing such incredibly boring things’. A second fan letter (from another writer living in a Richmond hotel) echoed this macabre theme: ‘. . . I thought I was addressing the author of that fine poem directly – Perhaps I was! Who knows. You will have the happiness of reunion, if not here, then on the other side.’

Theo did not consult mediums, despite being encouraged to do so by Gilbert and Lady Mary Murray, but reached out in other ways. She wrote, ‘One understands nothing about these things, one can only believe that there IS life after death.’ On Remembrance Sunday, 11 November, she recounted in a letter to EP, her heart felt unaccountably light and free – ‘as if Frank were happy that we had done something. I told Daddy – and I wondered what it was.’ They had sent his poems to be typed at last and had met delegates from Bulgaria. Perhaps, she wondered, on Armistice Day ‘when people’s spirits go out in such a wave of remembrance and love to the spirits of those who have died, it is easier for them to be in contact with us. Certainly nothing would so lift a burden from life as to know that Frank knew of our love for him.’

Graham Vivian might not yet have developed the gift for saying the right thing. EP, a tank commander in Italy, differed. When EJ wrote to him on 29 September, ‘This is a sad letter to write to you Palmer old chap,’ reporting Frank’s disappearance after 31 May, EP swore in reply that he and his brother had both had the happiest of childhoods. Edward replied, ‘No words meant so much to us as your saying that,’ and even Theo, writing independently, admitted that this comforted them ‘a bit’.

Though she and Edward tried to keep alive a faint hope that Frank might miraculously reappear post-war as a POW, Theo despaired. Her favourite son had died. She feared that her two boys had been conscious of strain in the home; she feared that they thought of the family house as a ‘stark, bleak’ place; she feared that her and Edward’s letters had been trivial and inadequate. She wished she had been the kind of mother who finds it easy to tell her sons how much she loves them, but knew her own stiffness and inhibition. ‘I hope you know, Palmer dear, how very much loved you are. Do you think Frank knew? Or was I too “fierce” – the old family joke?’ She could not express how trivial and vulgar their life seemed besides that of Frank. ‘That he, so greatly needed, should go. That we, so useless and second-rate, should be left to carry on. More than ever we pray for your safety & so longed for return.’

Edward echoed her. If EP did not survive the war, ‘there is literally nothing now for which we should want to live’. At least Frank had died without being troubled by the knowledge that EJ was fighting stomach cancer.

EJ told Theo she was wrong to blame herself as inadequate; it was nonsense for her to imagine that Frank did not know how deeply and purely he was loved. For his own part it never worried him if his own poems and many books – so much concerned with India – had made little appeal to Frank. EJ, born in 1886, conceived himself a late Victorian, his writing clogged with false and sentimental ways of thought. His consolation had been to hope that his two idealistic sons might help put the post-war world ‘grandly right’ while he, in honourable retirement, applauded. His letters had until this point abounded in facetious family in-jokes, and he had played the clown through three long years of separation. But intense grief can cut to the bone, through masks and poses, depriving us of the use of voices not absolutely true. Now, at last, he became serious, even solemn, enjoining EP: ‘It is now more than ever essential that you shall survive [this war] for it is by you that [Frank] will live on.’

The injunction to survive was the easier of two charges. The burden of memorialising and then of somehow representing Frank – ‘by you . . . Frank will live on’ – was a tougher assignment. Both EP’s first and his last published books – There is a Spirit in Europe (1947) and Beyond the Frontier (1997) – commemorate his adored elder brother. He was not a man to take responsibilities lightly.

The most exclusive unofficial club in 1945, Frank’s first cousin Barbara recalls, was that of bereaved mothers. Theo, to her credit, was too proud to make parade of grief or request sympathy on such terms. She wrote that ‘it seems sometimes unbearable that someone we all loved so passionately should have taken his resolve & gone his way so separate from us all – that we should have had no knowledge of this testing of his strong courage, no message of this victory, at the time . . .’ Her child had entered Calvary without her: the parallel is implicit in her decision to call Frank’s murder his ‘victory’. The family agreed. ‘He took his own way & made his own high choice.’

Theo blamed Frank’s ‘self-censorship’ for keeping the family from him so completely. Frank wrote ‘lovely, witty, darling letters. It is like having Frank in the room with you,’ she accurately noted. And yet he was far more discreet than other officers: ‘his letters could have been published with full military approval the day they reached us. He never mentioned operations, localities, units, anything.’ Theo understood that the needs of wartime censorship were somehow augmented beyond the call of duty by Frank’s private code of chivalry, a topic for the next chapter. The family had to deduce changes of unit by scrutinising his shifting addresses and guess even at changes in his rank. Putting together an accurate picture of his war was going to be difficult.

On 25 November Edward wrote to EP that he and Theo had ‘practically given up all hope of Frank . . . I am afraid the loss is not one we shall soon get over: you know how inexpressibly dear Frank was’ – the exact phrase used by his sister on the death of their brother (another Frank) in January 1917. As for EP, he noted a recurrent desire to find the precise point in the chain of causation at which the catastrophe began, as if the fateful story could then magically be retold differently, with a happier outcome.

On 29 November, fearful that EJ would probably pass it all on to The Times, SOE sent Bledlow the report of a Major Strachey. Snaffle Mission, which had dropped into Bulgaria, discovered that everyone there was speaking of Frank’s courage and endurance with the greatest respect: ‘He spoke our language and learnt our songs, he endured the danger and hardships with us during a time of ruthless repression . . . his name will not be forgotten.’ This, EJ wrote, was ‘the first comfort we have received’. Scott when captive had also been assured that Frank died bravely.

Further comfort was on its way. To a World Trade Union Conference at County Hall, London from 6 to 17 February 1945 came 204 representatives from sixty-three countries. Among two from Bulgaria was a schoolteacher named Raina Sharova, who had met Frank during his imprisonment and agreed to see Theo and talk about her son’s last days. Her account has been hugely influential in constructing Frank’s reputation as martyr-hero and she claimed, falsely, to have witnessed his execution.

‘The Story of a Great Englishman’ was published in the News Chronicle on 8 March: Sharova was its main source, Sofia radio and newspapers were others. Four officers died with Frank – one American, one Serb, two Bulgarians – and eight other prisoners. Fifty-seven of Frank’s companions had already been executed. Frank and the American were tortured – we do not know how, but some Bulgarians had their eyes gouged out.

Much of the article constituted a highly coloured account of Frank’s ‘show-trial’, with Frank answering bullying questions ‘in fluent Bulgarian’109 while calmly smoking his pipe: ‘I am ready to die for freedom. And I am proud to die with Bulgarian patriots as companions.’ At this a passionately weeping old woman stands up and announces that the audience sides with the brave Partisans. As she is struck to the floor, Frank and his Partisans are marched off to the castle where Frank raises the clenched fist of freedom, all the audience joining in, and he and his men die with raised fists too, in one version singing Botev’s ‘Anthem to Freedom’. The sobbing spectators declared this one of the most moving scenes in all Bulgarian history, and Frank now stood towards Bulgaria as Byron did to Greece.

This story was invention, propaganda by Communists seeking a legitimising heroic ancestry for the new regime.110 They decided – as Bickham Sweet-Escott, advisor to SOE’s Force 133, wryly observed – to turn Frank into a hero and Sharova was their stooge. She left an equally vivid account of meeting EP and Theo in London in February 1945 when EP was still in Italy. (Not all of this was fake. Theo’s eyes filled with tears when Sharova recounted telling the captured Frank not to despair as the Russians were approaching; Frank had replied: ‘I don’t despair. But time flies very fast.’ Theo gave her dried flowers to place on Frank’s grave.)111

EJ charged the War Office with not doing all in its power to uncover evidence such as this. Memos make very clear official embarrassment that the Thompsons by mid-1945 now knew far more – had many more details at their disposal – than the War Office itself.112 In the hostile stand-off between the Thompsons and officialdom, however, officials could not admit this.113

When the War Office sought hard evidence of Frank’s death in May 1945, EJ suggested it contact Raina Sharova. Under oath she swore on 14 November that though she had briefly visited Frank in prison ‘she did not, rpt not witness execution’. She would none the less prepare a statement about all facts known to her; the ACC, making other enquiries in the meantime, was suffering from the ‘habitual dilatoriness’ of Bulgarian bureaucracy. Sharova’s version of the execution scene was accordingly disavowed by EP in the second, 1948 edition of There is a Spirit in Europe: A Memoir of Frank Thompson. Yet it was – regrettably – resurrected in EP’s posthumously edited and published Beyond the Frontier (1997)114 and thus made its way into Frank’s current (2004) Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry.

EJ now had a reputation for being willing to ‘burst into print on the slightest provocation’. A 4 October 1945 SOE cable concerning the cancellation of a Bulgarian War Crimes Mission has ‘The Thompson Case!’ written on it, the exclamation mark suggesting that the whole anguished drama was being treated with a weary or cynical knowingness. On 6 November 1945 the newly elected MP Francis Noel-Baker asked the Secretary of State for War to make a full statement about the circumstances of Major Frank Thompson’s death.

Friends rallied. Gilbert Murray, expert on Greek tragedy, wrote: ‘You and Theo have gone very near the limit of human suffering this last year, and we think of you both constantly.’ Psychological torment apart, EJ was now in non-stop physical pain.

Probably because of their war with officialdom, the Thompsons never learned of Soviet culpability. The ACC in Sofia was dominated by the Russians both numerically and through their systematic humiliation of the British and (even more) Americans by means of petty and Kafkaesque restrictions on their numbers, movements and mail. Thus SOE had arranged in November 1944 for two of its officers, Colonel S. W. Bailey and Major Norman Davis, to proceed to Sofia to investigate Frank’s death. Davis had lived in Bulgaria, spoke the language (plus Russian) and was familiar with SOE’s work there from its earliest days; Bailey also spoke Bulgarian. For six months they waited patiently while the Russians prevaricated until SOE gave up. SOE’s subsequent attempt to bring in two further investigators, Major Macpherson and Sergeant Scott, fared no better. They were ‘kept on ice for months’, before being told to disband in October 1945. SOE noted that it was now absolutely unimaginable that the Russians would allow any Britons to roam the country asking questions. Was it best to tell EJ this in strictest confidence? They decided not to.

The family had been promised the first of Frank’s effects in April 1945 – two Bibles, one in Greek, one in English, plus a diary containing manuscript notes – but waited in vain for their arrival. In July a contrite letter from a Miss Lovibond at the War Office explained that she had learned that a soldier had to be Presumed Dead before his effects could be released. Frank was now so classified, his kit and belongings finally sent off on 10 July 1945, but by October the Thompsons had still received nothing. Without certification there could be neither probate, implementation of Frank’s will nor closure for his parents. Every single new enquiry necessitated fresh form-filling. War Office memos regretted ‘so many muddles, difficulties and delays’.

The journalist Ilya Ehrenburg – whom Frank idolised – broadcast from Moscow on 8 October 1945 that the British appeared not to know that those who had tortured and murdered Frank Thompson had been tried and executed. EJ wrote promptly to The Times, citing Ehrenburg and bitterly complaining of the many honours Frank had received in Bulgaria, comparing this with the shameful silence about his martyrdom at home.

Relief was at hand. On 4 March 1946 a Colonel K. Savill, investigating war crimes from 20 Eaton Square, was notified that the Bulgarians had after thirteen months’ delay written to the ACC providing the names of Frank’s murderers and their sentences. The Soviets were now increasingly in charge in Bulgaria and 2,000 convenient scapegoats had been found to indict and execute for some of the crimes of Fascism. Frank’s murder, which had contravened the Geneva Convention, was certainly one such crime.

In front of the Deputy Prosecutor, an Orthodox priest, the Secretary to the Court and a Dr Spirov, according to the letter to the ACC, the following five were found guilty of having shot and murdered seven Partisans in late May: Stoyan Lazarov (aged twenty-four), Angel Tsanishev (twenty-nine), Boris Vassilev (twenty-nine), Ilya Tupankov (twenty-four), Gorcho Mladenov (twenty-five), and the last-named was found guilty of having also killed and ‘persecuted’ eighteen people in battle. Most denied that they had fired at Frank – or claimed to have fired over his head. They were none the less executed at ten in the evening on 7 February 1945. Their families were also fined 100,000 lev each and one-third of their property was confiscated. By no means all details are accurate or clear,115 and nor was any explanation as to why this news had taken one year to reach the ACC in Sofia forthcoming.

Savill was welcome to pass all or some of this on to EJ ‘in case you deem it fitting’, a qualification suggesting the arrogant secretiveness that the Thompsons rightly resented, and a settled mutual hostility.

News came late for comfort. In constant pain for months and furious at his inactivity, EJ was at home in Bledlow, attended by Theo, EP and his nurses, approaching his sixtieth birthday and dying with hideous slowness. When EP asked whether he should tell Nehru, much involved with the run-up to Indian independence, EJ told him to mind his own business: Nehru had more important matters to worry about. No less a personage than the Viceroy Lord Wavell had brought Nehru in prison the news of Frank’s death; and Nehru, who wrote at length to his sister about Frank’s courage and his idealism,116 had also written movingly to EJ from prison about how much such friendships as his had meant to him over the long years of struggle.

EP disregarded his father, sent Nehru an air-letter and got a reply post-haste. One evening when his mind was clear from drugs, EJ sat up in bed reading Nehru’s letter thanking him for his life’s work on India’s behalf, before letting it drop upon the sheets. He died a few days later, on 28 April.