‘Stay away from Boars Hill’: 1919–33

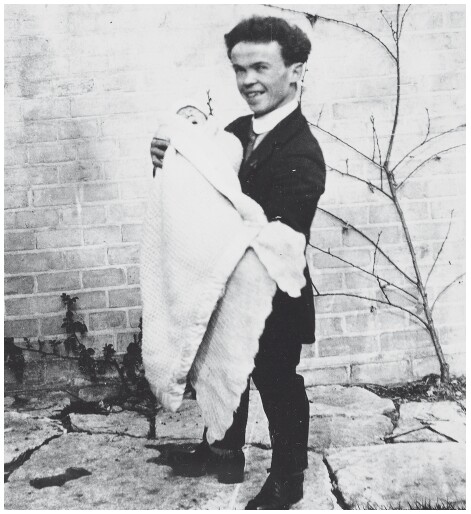

William Frank Thompson was born one month prematurely in Darjeeling, on 17 August 1920, and was piously named after his ailing grandfather William, who died that December, and after his recently killed uncle Frank. Obligation towards the family dead marked Frank from birth.

Theo stayed nursing her dangerously sick infant in the cool of the Darjeeling hills, while Edward 500 miles away in Bankura struggled alike with the heat of the plains and his religious vocation. Both Theo and EJ were proud, unworldly and new to compromise. A prophetic note of financial alarm runs through their letters. Although Theo was lonely and depressed, with only her ailing baby for company, EJ ‘can’t afford the ghastly expense’ of a month’s leave to join her; he had declared a Victorian husband’s willingness to ensure his wife’s days were free from care and so shrank from relying on her American income. On a Wesleyan chaplain’s salary they could not have everything, but Theo was unaccustomed to frugality. EJ begs her not to send her American relatives so ‘glowing a picture of our feudal splendour, servants and meals’.

Meanwhile, his disenchantment with God and Empire grew. Theo later recorded that EJ in 1910 felt entirely conventionally about Indian ‘sedition’, arriving on the sub-continent with no preconceived ideas of Indian independence. That was changing fast. One powerful trigger was the 1919 Amritsar Massacre when around 380 peacefully protesting Punjabis were machine-gunned and killed and more than a thousand injured. Further insults followed, such as Brahmins being forced to do sanitary work and Indians being made to crawl on all fours along one street where an Englishwoman – before being saved by nearby Hindus – had been assaulted. The missionaries, aided by EJ, wrote a mild letter of protest that won them considerable hate-mail. Tagore, as we have seen, returned his knighthood.

Though EJ fondly hoped that ‘English rule [was] still the sanest and fairest on the globe’, his faith in Empire as a force for good and in Christianity was shaken. At Bankura preaching was to gain converts; and depriving an Indian of his Hinduism without amending his poverty or the race-prejudice that justified that poverty was doubly insulting. He increasingly abhorred Methodism’s exclusive, macabre doctrine of conditional salvation, the record of every sin and wicked word chronicled in ‘[the] Dreadful Book’. He disliked its emotional blackmail sugared over with concern for the soul’s eternal safety. As early as 1912 EJ had written to his pious, simple mother complaining of the cruel doctrine of hell-fire: ‘If everyone who dies in a certain condition drops into a hot bath . . . it wd be wicked & the act of a fiend. Even if the Bible teaches it, it isn’t true.’

His fellow missionaries were uncongenial and EJ sent in a letter of resignation to take effect in 1923. He spent time writing on Tagore. As well as explicating what he found marvellous in his work, EJ had the courage to criticise the cult of Tagore, who scolded the West for loving comforts even as he earned fat lecture fees in the USA, travelling with his secretary in his own private railway compartment. EJ’s own powerful missionary impulses, increasingly homeless, henceforth went into questioning and trying to reform British imperialism in India, partly by explaining Tagore and Bengali literature to the British. After considering living in the USA, EJ was offered a lectureship in Bengali at Oriel College, Oxford, which Theo conceded the equal of Princeton. He sailed by himself on 23 January 1923 to look for family lodgings, while Theo and Frank waited four months in Beirut.

On her arrival in Oxford that May, Theo was thirty-one, having lived eighteen years in Syria, nine in the USA and four in India. When EJ told Theo he had met at Port Said another pretty, highbrow ‘Amurkan’ girl, evoking her ‘comical, drawling’ speech and shallow culture, his description stung: sharp letters ensued. Theo had been educated by governesses, two good, one bad, and then at two first-rate institutions (the Packer Institute in Brooklyn, and Vassar), but superficially. True, a Columbia year trained her to teach English, which she did at Smith College in 1917–18. But her Vassar BA split between fifteen separate subject-areas had given this highly intelligent young woman no deep or confident grounding in any. In later life she accounted herself fortunate that, so ignorant did she remain, there was always plenty to learn.

In London en route for India she asked her sister Faith to blindfold her in the British Museum, lead her slowly up to the Elgin Marbles and remove the cloth (neither knew that these were plaster-of-Paris replicas, the originals stored for safe-keeping against Zeppelin raids). Theo was enraptured, too, by London Bridge, the Tower, everything. The Thompsons furthered her education. Theo asked EJ’s sister Margaret a hundred and one questions, ‘about shops, room-rents, the best places to buy things, customs that are a bit different from American customs &tc . . . I am using her as a combination encyclopedia & traveller’s Guide.’ And EJ continued Theo’s education, starting with Boswell’s Life of Johnson.

His high-sounding post in Bengali at Oxford University turned out to be part-time, teaching Indian Civil Service probationers vernacular Bengali. It carried no university membership, and the salary was £160 a year, plus £5 per student. Since he found only one student awaiting him, he was free, once he had mastered Sanskrit, to give time to literary studies and his own writing. But this salary did not even meet his rent – ‘cruelly expensive’ – for two Oxford rooms. After six weeks they moved to picturesque Islip, seven miles outside the city, with fishing rights on the river, down which some congenial neighbours, the poet Robert Graves and his energetic wife Nancy, together with their children, soon came to call in a canoe.

Graves wrote to his mother that the Thompsons were their closest educated neighbours, he a north-country man ‘& Wesleyan Minister, a very good man who plays football’. The two families met most days, sharing picnics, Christmas dinner, guests and children’s parties. Few of Theo’s Vassar friends could visit Oxford, but she and Nancy liked and admired each other and sympathised with each other’s troubles, surviving such mishaps as Nancy driving Theo so hard into the pavement that a wheel of her car fell off. Both Nancy and Theo in their respective marriages ‘wore the trousers’; both were devoted, headstrong and occasionally sharp-tongued; each directed a formidably intelligent, future ‘Great Writer’ in whom she believed. When Nancy had her fourth child, Theo and EJ looked after her previous three for some days.

Nancy was interesting. The wilful daughter of the painter William Nicholson, sister of the artist Ben, boyishly slim and stylish, she made all her own and her children’s clothes, wore a land-girl’s breeches instead of skirts, no wedding ring, and refused to go to church or have her children baptised. She assured Robert that the age-old sufferings of women exceeded the Great War traumas he would memorably chronicle in Goodbye to All That. House chores were accordingly shared and on feminist principles she and her two daughters kept her maiden name of Nicholson while her two sons used Graves: Virginia Woolf relished this provocation. Nancy made some of their furniture and bicycled around Oxfordshire smoking Woodbines, setting up stall and giving village women free – and illegal – contraceptive advice: something she had missed when producing her four children in four years (her health suffered as a result). Baths were communal, she and Robert always soaking together. Both Thompsons appreciated the Graveses’ bohemianism.

Nancy wanted Robert and herself to be ‘dis-married’ so that they could live together without religious or moral obligation; Islip folk were not impressed by the contempt with which she treated her husband, as a ‘representative male’. As for Graves, an eighteen-stone student at St John’s College, patrician in manner and profoundly shell-shocked, he had a strong streak of masochism and a love of submission. He indulged Nancy in 1920 when she insisted on opening a traditional village shop on Boars Hill, an adventure that lost them both a great deal of money.

The friendship between Graves and EJ thrived: both were traumatised war veterans with progressive views, struggling to make their names as writers, though Graves was better connected, visited even then by T. E. Lawrence, Siegfried Sassoon, Edith Sitwell and the Asquiths. EJ was soon to edit the poetry of Graves – as of Masefield, Bridges and Tagore – for a sixpenny poets series published by Ernest Benn which sold well but was incompetently managed, a source of continuing aggravation. Graves sympathised. Meanwhile Nancy designed the cover for EJ’s novel An Indian Day, among the few commissions she then received.

Soon they were no longer neighbours. In 1926 Graves and Nancy sailed to Egypt where Graves briefly took up an academic post that proved disastrous, together with a neurotic American poet called Laura Riding, so fierce a dominatrix that Nancy by comparison seems easy-going. Graves assured EJ with self-serving optimism that ‘It’s lucky that Laura and Nancy are each other’s best friends . . . so there’ll be no trouble.’ Over the following three years, a painful and unstable ménage à trois evolved. ‘It seems a pity that now the Turks have given up polygamy,’ Nancy’s father jested, ‘Robert should have decided to take it up.’ Shocked, he withdrew her allowance. Nancy largely brought up the four children herself, on little or no money. When her daughter Jenny wished to learn to be a dancer, Nancy, unable to afford a London rent, bought a hulk on the Thames near Hammersmith on which she built a Noah’s Ark of a house, incurring only the costs of wharfage.

When the Thompsons moved to a rented cottage on Boars Hill,7 EJ, who had recently won a London PhD for what became his Tagore: Poet and Dramatist – a book Tagore and other Bengalis found patronising – was in February 1925 elected an honorary Fellow of Oriel. Theo, emboldened, bought some land near by and commissioned an architect to build a comfortable residence with a large hall and big stairway of dark polished oak, set in two and a half acres of grounds. The back windows gave a splendid view of their land: a long broad slope wooded at the bottom with the Chilterns in the distance. They kept a mare whom they exercised. An idyllic setting in which to bring up two boys, they named it Scar Top after the Penrith farm where EJ’s father had grown up. There were promising neighbours.

The archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans, short, thickset and imperious, invited the Thompsons to walk in his nearby sixty acres of grounds, bluebell-filled in May, and to swim and canoe in his two-acre lake – a privilege not extended to all. Youlbury, his vast, ugly, rambling twenty-two-bedroom mansion, had an elegant Siena-marble pillared entrance hall with a Minotaur mosaic on the floor. Evans was from 1894 also the owner, excavator8 and in a real sense the lordly inventor of the equally fantastical Palace of Minos at Knossos in Crete. Its principal works of art were exhibited in London in 1903, and in spring 1938 Sir Arthur helped Frank to get to Crete to excavate there.

Evans’s letter-cards to EJ, forty years after his wife died of TB in 1893, are still heavily black-bordered: ‘protective colouring’, his half-sister Joan suggested. He had at the age of seventy-three been charged with an act of public indecency in Hyde Park with a young man – possibly an aberration – and he reputedly preferred boy-visitors to girls, but neither prevented his Twelfth Night parties for children being a highlight of the calendar. Evans danced with all and sundry and held the Thompsons in evident affection, calling round repeatedly at Scar Top during the summer of 1939 – despite approaching ninety years old – in fear of missing the right moment to wish them farewell.

Evans’s telephone number was Boars Hill 10. Boars Hill 1 meant the Greek scholar Gilbert Murray and his wife Lady Mary, at Yatscombe, where they had retired in 1919 for the last decades of their long lives. Strictly vegetarian, teetotal and non-smoking, they personify Matthew Arnold’s famous dictum about Oxford as ‘home of lost causes . . . and impossible loyalties’. Lady Mary during the May 1926 General Strike was seen, aged sixty, pushing her pram the eight miles round trip into Oxford to collect her shopping rather than pay a scab (blackleg) volunteer bus driver. She had inherited Castle Howard from her father the Earl of Carlisle, before exchanging it for a consideration with a brother. George Bernard Shaw caricatured Murray as Adolphus Cusins, and his dictatorial mother-in-law as Lady Britomart in Major Barbara (1905), while Major Barbara’s own passionate idealism was directly based on Lady Mary’s – Shaw’s working title being ‘Lady Mary and her Mother’. Lady Mary inherited a large measure of her battle-axe mother’s monstrous bossiness, censoriousness and humourlessness.

Lady Mary was essentially kind-hearted too. But her odd upper-class mix of high-mindedness and high-handedness was on display when EJ arrived with his second, younger son EP for luncheon one day. She had insisted on this call, even though it was highly inconvenient, so call they did. She petted EP, who played the role of guileless little angel, remarking on his goodness but, soon switching to hauteur, was also outrageously rude. The worst outburst happened after EJ said he hoped the Labour Party would, if they got in, tackle Britain’s problems and not tie the country up with irrelevant experiments as in Russia. She flared up at any criticism of the Bolsheviks. Murray, embarrassed and keen to put things right, later explained on a walk that, like many Labour people, Lady Mary had a fierce emotional feeling about Russia: ‘My wife thinks the Bolsheviks are a kind of Quaker.’ Murray was once asked in an American questionnaire whether his marriage was 1) happy, 2) very happy, 3) very, very happy, 4) unhappy or 5) disastrous. But – despite prolonged reflection – he confided to EJ that he had not yet arrived at a suitable answer.

Murray, who was the Regius Professor of Greek, lived halfway between the great world and the academic world, at home in neither. Visitors eating his nut cutlets and sipping his orangeade included Bertrand Russell (a cousin by marriage), H. G. Wells and Julian Huxley. This Murray confraternity with progressive intellectuals may be one reason why, in Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, Charles Ryder’s cousin Jasper gives him early the memorable life-advice: ‘Stay away from Boars Hill,’ home to the smart Fabian-socialist movers and shakers whose influence Waugh feared and hated. Lady Mary’s rebellious son, Basil Murray, Waugh acknowledged as a model in two novels for the attractive, caddish Basil Seal.

Lady Mary influenced Theo. Alert to the differences between what later would be termed U and non-U behaviour and wanting to do the right thing socially, she took seriously Lady Mary’s say-so that in England children of good families ‘never have butter and jam on their bread’. And Theo never fully recovered from the shock of learning from her that in England you cannot be both Methodist – as, by marriage, was Theo – and upper class at the same time. Forty years later Theo still pondered this conundrum. Of course England and the USA differ profoundly: there have been five Methodist presidents of the USA and no Methodist prime ministers of England. Lady Mary became a Quaker in 1925, and after the Second World War Theo emulated her.

Gilbert Murray, courtly, idealistic, shy and with an innate revulsion from cruelty that unfitted him for modern life, was working with his friend Robert Cecil from 1918 for the League of Nations Union. In case such duties left him insufficient time for his academic responsibilities, Murray typically offered up half his salary to fund a readership in Greek. He was another of EJ’s mentors, who read some of EJ’s drafts and wrote encouraging him in a tone of gentle and good-humoured teasing and ironic badinage. EJ had only a toehold in the academic world, and little hold at all on the great world: Murray’s friendship flattered him.

Robert Bridges and John Masefield – two successive Poets Laureate – were other close neighbours whom EJ, wishing to make his own name as a poet, did not neglect. Both are old-fashioned, pre-modern, nature-loving and, like EJ himself, largely forgotten today. EJ, collecting signatures during the General Strike in favour of compromise or mediation, found both neighbour-poets too conservative to sign.

EJ visited Bridges in 1914 when explaining the new Laureate to the Indian press and first encountered his bright eye and abrupt, challenging manner. Bridges would enter Scar Top unannounced to read books in EJ’s library and complain if a book were not where he expected to find it. After playing whist with him EJ noted that ‘the old man [was] at his worst, a selfish battening pig whose pose of being bored by, & superior to, everyone you cd mention, was tiresome’. EJ thought Graves not far wrong to call Bridges a ‘silly old man’. Such acerbity did not prevent EJ writing Bridges’s biography.

EJ’s acquaintanceship with Masefield, with his shy morning smile and love of Chaucer, was kindlier. Like EJ, Masefield had had to leave school to work (at sea) from the age of sixteen, was therefore self-taught and had suffered during the Great War. He built a private theatre in his garden. Here the Thompsons, with other neighbours, casually acted, and EJ later recalled ‘the nightingales singing all about us’ while they were rehearsing Masefield’s play Good Friday. The Thompsons’ cat Pushkin appears as the black cat Nibbins in Masefield’s children’s story The Midnight Folk, and Masefield inscribed on the flyleaf of the copy he presented to Scar Top ‘To Frank Thompson from John Masefield 1928’ together with the author’s drawing of a witch.

Frank’s youthful head was too large for his body, so that Robert Graves later remembered him as ‘that imperturbable top-heavy child of 1924’ and witnessed him, aged only three, dividing his chocolate into four to share with the Graves children: perhaps altruism might be an aspect of his character? That year, 1924, Theo gave birth to her second boy, Edward Palmer, named after both EJ and a long line of Palmers on her side of the family; Palmer was a name he increasingly resented and the cause of many family rows.9 Another neighbour when the Thompsons first came to Boars Hill, meeting Theo wheeling round a baby with curly blond hair, thought it was called Pamela and a girl. The brothers got on and were ‘best friends’. Sibling love, unlike sibling rivalry, is not a fashionable topic nowadays, but these boys none the less loved each other. Late in life Edward still relished Frank’s clowning: ‘Frank, you’re sitting on a cheese sandwich.’ ‘No I’m not: it’s a tomato sandwich.’ A simple joke to charm a younger brother, and a charm still operating sixty years later.

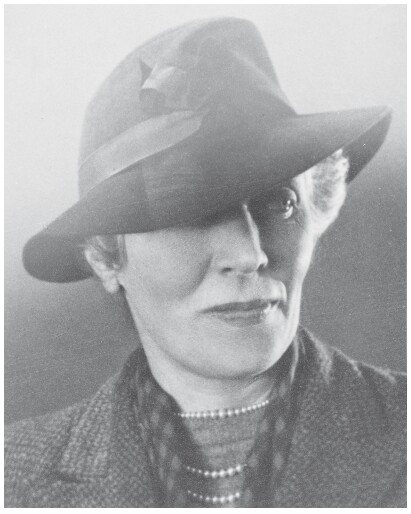

Frank and ‘Little Ma’, EJ’s mother, 1924.

Frank asked questions endlessly from a brain working every minute, and soon there was education to ponder. Theo considered Dora Russell’s newly opened progressive Beacon Hill School in Sussex but, when she took Edward down, in the same room where Dora interviewed them were also several young pupils straining thoughtfully upon their potties. Theo couldn’t get away fast enough. She opted to send both her boys to the already fashionable Dragon School on the Bardwell Road in North Oxford. Dragon alumni include Hugh Gaitskell, John Betjeman and EP’s classmate John Mortimer, who fictionalised it as ‘Cliffhanger School’ in his play A Voyage Round my Father. Three other Boars Hill families sent their boys there, all making their turbulent way in together by bus – unaccompanied in those safer days by any adult. Each of the fathers of the Boars Hill gang, as they became known, was an Oxford don.

Frank and his brother EP, c. 1928.

The father of the two neighbouring Gardner boys10 was a bacteriologist at University College who ended up as Oxford’s Regius Professor of Medicine. There were Rex and John Campbell Thompson – known always as the ‘Cannibal Thompsons’ and no relation – whose mother was descended from William de Morgan, friend and acolyte of William Morris, and whose home – full of de Morgan tiles – was an education in Art Nouveau. Reginald Campbell Thompson, an Assyriologist at Merton College, had with T. E. Lawrence in 1911 excavated Carchemish, an ancient city on the border between modern Syria and Turkey. Frank later accounted Rex and Brian Carritt, ‘my only two friends of life-long intimacy’. He and Rex went together for the first time to the Dragon in summer 1928, and Brian, youngest of the Carritts, followed soon after, and excelled at both sport and lessons, becoming head boy. Each family lost children to the war.11

The Carritts at Heath Barrows were closest to the Thompsons. Edgar Carritt lectured in Philosophy and was a Fellow at University College with a troubled marriage: his beautiful wife Winifred was an exceptional musician, frustrated not to have had a career. Their son Gabriel believed that Edgar ‘admired the bodies of young men more than those of young women’. Edgar and Winifred separated for a time after her lover – who had sired Anthony, one of her five sons – was killed in the Great War.12 There were two girls in addition to the boys, an expensive cohort to maintain. The Carritt children famously ran naked around their seven acres of wild garden shared with three goats, two pigs, hens, ducks and bees in their hives; they painted themselves in bright colours, believing that everyone did. The cooler months found them in roughly patched and darned hand-me-downs. Food and blankets were scarce and W. H. Auden, in love with Gabriel, was notorious for taking up the Carritt stair carpet to put on his bed in an attempt to stay warm, then raiding the larder at night to wolf cold potatoes and leg of lamb. Auden wrote poetry inspired by Gabriel’s physical beauty and athleticism and found his company restful. Guests were an event. Stephen Spender, who was being tutored by Carritt père and who, like Auden, fell in love with Gabriel, visited, as did Richard Crossman, later a Labour Cabinet minister, who sarcastically called his set ‘the golden boys’.

Frank, too, came to stay, his best friend being Brian Carritt, one year younger and, like his brothers, at the Dragon School. Brian, aka ‘Tow’, blond, clever and good-looking, swam with Frank in Evans’s lake, and they made up games of lurkey (kick-the-can) in the shrubbery and ‘chaotic and murderous charades’: no other outsider apart from Brian was so much a part of the Thompson family. One Carritt sister, Penelope, died of anorexia in 1924 and Gabriel put her virtual suicide down to family unhappiness, something to which her five brothers and their musical mother Winifred found a quite different solution: all six joined the Communist Party.

These Oxford dons’ intellectual-bohemian families in their Betjemanesque villas – the Thompsons at Scar Top, the Carritts at Heath Barrows, the Gardners at Chilswell Edge and the Campbell Thompsons at Trackways, together with another new friend, the artist Hilda Harrisson at Sandlands – recall John Betjeman’s spoof poem ‘Indoor Games near Newbury’ with its evocation of well-to-do Berkshire families between the wars (Boars Hill was then in Berkshire) living at Bussock Bottom, Tussock Wood and Windy Break and giving off a sense of social advantage.

EP, EJ, Theo and Frank: Thompson family picnic, c. 1933.

Michael, third eldest of the Carritt children, analysed this Boars Hill world further: such Oxford dons and their families, he believed, represented a small but influential sub-group of the upper-middle class – the academic intelligentsia – who lived in and were encouraged to absorb the rarefied atmosphere of a self-conscious elite. This coterie, set apart by their ‘cultural excellence’, accepted the duties, and claimed the privileges, of that pre-eminence. Egalitarian yet elitist, here was one pre-war forerunner to champagne socialism or ‘radical chic’. Everyone knew everybody else worth knowing.

EJ and Theo took the view that there were ‘top people’, artists, intellectuals and great political leaders, who shared an atmosphere above politics and nationality. Perhaps Boars Hill might provide entrée.

John Mortimer depicts the Dragon School as progressive and engagingly dotty. Schoolchildren had to address Dragon masters by their nicknames such as ‘Shem’, ‘Ham’ and ‘Japhet’. (This mode of speech of ‘Noah the Head’ – A. E. Lynam – mingling Kipling and the Old Testament, was soon borrowed by EJ in his letters to his sons, which contain facetious injunctions like ‘Rejoice therefore!’) Pupils could bicycle round town and take boats on the river. At concerts where the boys drank cider-cup, the masters sang ‘Olga Pulloffski the Beautiful Spy’, ‘Abdul the Bulbul Ameer’ and ‘Gertie the Girl with the Gong’.

The Dragon had a pre-school that took children from the age of six, and Frank, with all his fierce inquisitiveness, was there by 1928, aged seven and a half, Edward following in 1930. On arrival Frank was not merely top of his class, but so far ahead of his age group that he had to be moved up two forms by that September. In this new class, though the youngest by two years, he still came second. He soon won prizes for Classics, French, appreciation of English, Recitation and Reading, and at twelve won the Fitch award for ‘one of the best essays ever produced’ on the topic ‘Our civilisation is no better than that of the Greeks and Romans’. Precociousness dogs his story: aged seventeen on Crete in 1938 he would be asked where his wife was, and aged twenty-two in Egypt would take command of troops ten years his senior.

From 1930 to 1933 Frank and Edward overlapped at the Dragon and experienced contradictions in their relationship. Young EP, wrongly thought a dimwit, was awed by Frank’s brilliance. EP, however, excelled at sports while Frank, ill as an infant, did not catch up on his own strength till he was twenty-two. Robert Graves’s reminiscence – Frank as ‘top-heavy’ with a large head too big for his tall, thin body, uncoordinated and accident-prone – was accurate. Frank had private lessons to correct his lisp. He was forever breaking things or knocking them off tables, and as late as May 1943 wrote home, ‘Thompson is not popular in the mess at the moment – last night I broke a chair while telling a Russian joke.’

A maladroit, lisping child may attract bullies; and Edward would intervene with flailing fists and tears to try to protect his elder brother. But Edward, aged only six or seven, was too small to help – hence his tears. Here is a central motif in their relationship. Frank had a reckless disregard for his own safety that afflicted Edward with intense protective anxiety. That later in 1944 he inspired a deeper anguish through the manner of his death no doubt intensified Edward’s recollections of early woe, and Frank’s end rendered Edward’s protective anxiety about him permanent. The theme colours their childhood. Around 1935 Theo and EJ sent the boys to the Norfolk Broads to learn to sail. Instructed to splice two ends of rope together Edward succeeded while Frank, after five minutes, failed miserably and was – to Edward’s chagrin – heavily rebuked. Edward hated his own success being used to humiliate Frank. But both Frank’s brilliance and his ungainliness set him apart. Frank accepted his clumsiness stoically and learned to turn it to comedy, exploiting it to buy popularity.

It is striking that Edward recalled the Dragon as ‘robust, brutal and nasty’. His exact contemporary John Mortimer enjoyed it, and (unlike Frank) simply evaded uncongenial sports. Young Edward, by contrast, excelled at both sport and drama, those twin Dragon specialities. Mortimer recalled Edward at nine, his socks round his ankles, rushing after a ball while Mortimer shivered miserably near the touchline. Each year a Shakespeare play and a Gilbert and Sullivan operetta were put on and cast democratically – by popular vote rather than by audition. Frank rose only to the walk-on role of a mariner in The Tempest, while Edward was elected to play John of Gaunt to John Mortimer’s Richard II. Both Edward and John Mortimer adored acting, but Edward’s popular success evidently did not attenuate the more potent memory of Frank’s loss of face.

A few girls – if daughters of an Old Dragon or staff member, or sisters of a boy already in school – were welcomed: the future writers Naomi Mitchison and Antonia Fraser were two such. Girl Dragons had a reputation for succeeding at whatever they set their mind to do, rugby included, but numbered at any one time out of the whole school of 140 only between six and twelve. Girls, generally, were in short supply. EJ had two sisters: Margaret was married to Charles Pilkington-Rogers, a headmaster in Retford with one daughter, Barbara (aka ‘Tubsie’), with whom they spent Christmas; Mollie married Charles Vivian, a doctor and a kindly British Israelite living in Leighton Buzzard, who, knowing that his poorest patients could not in those pre-NHS days afford to pay him, simply neglected to charge them. He had three children: Trevor and Graham became professional soldiers, and the charming and witty Lorna Vivian, with a congenital heart condition, helped introduce Frank and Edward to pony riding. Those two girl cousins apart, the Thompson boys’ childhood world was largely masculine; it was Theo, however, who ruled the roost and administered punishments when needed.

EJ, that lifelong outsider, yearned to belong in Oxford and yet found its rituals ossified. Meanwhile he continued to educate the British about India. Apart from books on Tagore and poetry, he wrote plays – Atonement (1924) and Three Eastern Plays (1927) – A History of India (1927), a study of suttee or Hindu widow-burning (1928), two novels – one fictionalising his time in Bengal, Indian Day (1927), another fictionalising his war in Mesopotamia, These Men, thy Friends (also 1927) – and Crusader’s Coast (1929), a study of the Levant from which I learned that two of the murderers of St Thomas à Becket are buried under the Al Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem (Frank would travel the Middle East during the war with his own copy). It was a prolific but uneven output.

Most notably in 1925 he published his first work of history, The Other Side of the Medal, which created a scandal. Here was a pioneering study of the so-called Indian Mutiny of 1857 from the Indian point of view. It made no bones about British chauvinism or cruelty, and demonstrated a continuity of stupidity and bad faith between 1857 and the 1919 Massacre at Amritsar. EJ expounded many Indian grievances – not merely the sepoys famously having to bite open the ammunition for the 1853 Enfield rifle greased with lard, unclean to Muslims, or tallow, anathema to Hindus.

He itemised the massive British revenge-killings, with rebel sepoys tied to the cannon muzzles (a traditional Mughal punishment for rebellion) and blown apart. This was a brave book, and justly made his name. Since he was partly funded by the India Office, he had also risked his livelihood. Robert Graves was not alone in congratulating him on his courage and success – though EJ must have envied the huge sales Graves enjoyed with his best-selling biography of T. E. Lawrence, Revolt in the Desert (1927), which was followed by Goodbye to All That (1929) and the Claudius novels (1934 and 1935). EJ was now an India pundit. The publisher J. M. Dent soon wrote asking him to write a book telling ladies outward bound for India how to get servants and what the correct etiquette was for each occasion. He begged with due irony to be excused as ‘unqualified to advise on these high problems’.

On the 150th anniversary of the Mutiny in 2007 a British publisher declined to republish The Other Side of the Medal on the grounds that it looked today insufficiently radical. EJ did not call for British withdrawal from India but wished to restore the confidence of Indians in the Empire. Especially in the UK today there is a tendency to patronise EJ as an outmoded liberal believing against the odds in the British Empire as a potential force for good, from which Indians were wrong to wish to separate themselves. Yet his emphasis throughout his life on the need for a spiritual reconciliation between Britons and Indians was entirely appropriate for a man who saw himself primarily as a poet with religious promptings, rather than a politician.

To some degree EJ has been the victim of his own success. The reconciliation he so passionately favoured has come about, and so now belongs to history.

What of Theo? At this point she interests me more than EJ. In a report to her old college, Vassar, she lists as occupations ‘Keeping in touch with friends and events in India and the Near East. Writing. Gardening. Producing children’s plays.’ She wrote a touching one-act play about Miriam – Hebrew name for Mary Magdalene – co-publishing this with EJ as one of their Three Eastern Plays in 1927, and collaborated with EJ in writing one other play in the 1930s. But if she saw herself as a writer, she was a frustrated one. Theo’s diary-notes from 1925–31 manifest dissatisfaction. The first year at Scar Top was a tiring business.13 For three months early in 1926 she was ill in bed getting what she called ‘heart attacks’ – possibly panic attacks. She saw a specialist on 5 March. EJ’s mother helped with the children while Theo spent two weeks in the Acland Hospital on the Banbury Road. ‘Miserable time,’ she writes. ‘Dr Good tried to “analyse” me. I hated the idea of meeting clever people – was afraid of the ladies of the Hill – all except the most domestic and helpful ones. Felt a fool with good talkers . . . Dreaded coming back to entertaining & any social life . . . Palmer developed a horrid mouth sore – pronounced impetigo – think rather it was due to nervous trouble.’ On a photo of herself holding Frank she scored through her own face; she later destroyed a commissioned portrait of herself by a fashionable painter, finding it unflattering.

Her isolation comes across: no mother to advise or back her up. She had mothered her own younger sisters Faith and Jo, while neither Little Ma (EJ’s mother) nor Mother Kate (Theo’s disliked stepmother) offered much support. Theo belonged to a generation of educated women who lived the lives of their husbands more than their own, only half aware of their anger and resentment.

By Good Friday 1926 she has recovered enough to visit the kindly Masefields, and by the end of May starts having a friend or so in to tea. Her diary-notes – ‘Lunch with the Murrays . . . Sir Arthur [Evans]’s reception . . . Tagore calls . . . Storm Jamesons for weekend . . . Frank given a boxing lesson or two by Dr Campbell Thompson . . .’ – suggest a resumption of social life, and she occupies herself that summer with ‘Jam making (strawberry, blackcurrant), cake making, hay making’. Yet a twice-repeated phrase ‘plagued with woodlice’ sounds the note of estrangement. Each aspect of her environment evidently had to be managed: even woodlice, not normally thought of as constituting ‘plagues’ unless to someone with a remarkable love of control?

Two visits from Nancy Nicholson, the first with her children, the second with Laura Riding and Robert Graves, provided food for thought. Trapped in a triangular relationship resembling the one depicted in Noël Coward’s 1933 play Design for Living, Nancy even ran up on her sewing machine in 1926 a trousseau of dresses for Laura Riding to take to Austria, effectively on honeymoon with Robert Graves, while she – Graves’s wife Nancy – stayed behind looking after their children. Nancy was victim to her own instinctive iconoclasm, her ideals forbidding expression of jealousy.

Theo was one of a rapidly growing audience to a notable tragicomic scandal but also an unusual friend with the rare good sense to proclaim sexual jealousy a natural emotion. The Graves ménage à trois became a folie à quatre when Laura declared the Anglo-Irish poet Geoffrey Taylor a fourth player. The latter vacillated, however, and Nancy agreed on Laura’s behalf to go tamely to Ireland to entice Geoffrey back, only to find him falling in love with Nancy himself; she reciprocated.14 Her marriage finally at an end, Nancy, her four children and Geoffrey moved to Sutton Veney in Wiltshire, where she started the Arts and Crafts Poulk Press from a house she and her family built out of Baltic pine. Frank’s 1941 reference to Graves as ‘that man’ accurately records his family’s view of the matter: Nancy remained a good friend to Theo.

Compared with Nancy’s dramatic problems, Theo’s, however painful, must have seemed small beer, domestic and bourgeois. Among her comforts was a handsome dwarf manservant named Albert who had been with the Thompsons since Islip days, part of the furniture in that first house they rented when they came to Oxford. Theo scaled down the Scar Top kitchen to fit him. Albert was handy with clothes-making, running up ‘a second pair of small grey flannel trousers’ for EP, bringing Theo breakfast in bed, caring for funny good-tempered little Sandy the dog – half poodle, half Scots terrier – and daily weighing Pushkin the family cat. From time to time Albert would send his photograph – head and shoulders only – to marriage agencies, looking, unsuccessfully, for a partner.

Albert’s acquisition of a motorbike during the General Strike was useful as the Thompsons possessed neither telephone nor car. Trips as a result seemed a great effort, life ‘a dragging affair’. To go anywhere – Wantage, the White Horse, Burford – meant ‘catching buses, carrying bags &tc & was a tiresome business’. Theo was mainly housebound, the garden heavy and hard going despite help. While never openly questioning her ‘wifely’ role, Theo felt secretly thwarted. She did not have her friend Nancy’s resourcefulness or ability to reinvent herself.

Then there were headaches – and rows – about money. In 1927 Theo noted ‘V. depressed Jan 23 & wonder if we can afford to stay at Scar Top or shd try for job in America’. They spent 1929–30 in Poughkeepsie, New York State, where EJ lectured at Vassar for $4,000 a year, the boys going to a public school and Theo catching up with her family. It was a year plagued by ill health, all four Thompsons sick with different ailments; EJ – whose mare had kicked and broken his leg – travelled on crutches and was in and out of operating theatres and hospitals for years afterwards. American condescension towards British difficulties in India irritated EJ: it came with no acknowledgement of the many unpunished lynchings of blacks happening each year in the American South or of their own race-based caste system. The boys returned with temporary American accents and Theo built in the Scar Top garden a Baalbek summer house, expression of her longing for elsewhere.

EJ had no inherited wealth of his own and got by on his teaching and writing. By marrying Theo – who came, in his own charged phrase, from ‘Moneyed People’ – EJ was marrying out of Methodist puritanical poverty. A stylish, scented grande dame whose clothes, food and furnishings were elegant, a social mover with ambition and occasional assurance – keeping house by itself scarcely exhausted her abilities.

What Theo required in order to pay for her custom-made clothes alone was redoubtable. Like Kingsley Amis and John Osborne in a later generation who both ‘married up’, socially speaking, what attracted EJ also affronted him. Scar Top was paid for from Theo’s family money and she later said that she thought it very snobbish of the English to look down on a husband who used his wife’s money for a house. He resented both Theo’s spending and his own dependence on her capital. When Theo, her two sisters and the two boys went out to the Lebanon in 1927 EJ provided a sum of money which Theo mistook for ‘pocket money’, buying them all new bits of clothing and small luxuries only to discover too late that it was the money for the whole long journey. After she had paid the fares there was nothing for food or extras.

In 1933 EJ told Masefield that Scar Top was for sale. In the event they stayed another six years, but anxiously. Edward later recalled either lying in bed and hearing his parents fiercely quarrelling, or weeping at the top of the stairs at the emotional storms beneath – mainly, he thought, about money. His parents kept separate bedrooms, a common practice then among educated people, without necessarily signifying a mariage blanc; but Theo was frustrated and unfulfilled. Moneyed assurance combined with intellectual self-doubt. She quarrelled with a succession of maids, as with her husband, who was doubtless impatient, impetuous and sometimes pompous and sardonic. She was bossy and controlling with her boys, who loved her but feared her moods of needing to organise others.

A big change was getting the first family car – an old Austin – in 1930. Theo alone drove the first year, hating it, ‘an agonizing business’. In the beautiful summer of 1932 Edward learned to drive and took the family nearly 100 miles towards Devonshire. Soon an open-topped Morris replaced the Austin before giving way in turn to an old Armstrong Siddeley.

In early June 1933 Theo, young Edward and Sandy the dog walked in Sir Arthur Evans’s woods with Frank’s Winchester scholarship exam schedule so that they could calculate exactly when he finished his Greek exam (‘which we think was easy’) and began Maths 2 (‘which we think was hard’). Such strenuous attempts to guess at the lives elsewhere of those you loved would, when war came ten years later, be a national pursuit. Theo and EP imagined Frank scanning the questions . . . and indeed it is startling to find from his Bodleian papers that Frank was that afternoon giving each question his personal grade, from ‘Good’, ‘Fair’ and ‘Hard’ to ‘Easy’ and then – quite often, and showing no lack of chutzpah – ‘Potty’.

Frank and Theo.

Theo had sent Frank detailed instructions on how to behave if summoned for a Viva: ‘Recall you are only 12 years old, which will count in your favour, and . . . say to yourself “In three hours or so it will all be over and I shall be on my way home.”’ Frank won a scholarship to Winchester. The headmaster of Rugby, his school of second choice, sent his congratulations, making clear Rugby would also have welcomed him. ‘Wonderful school,’ Theo jots on this letter. ‘But not quite up to Winchester.’ Her elder son was to be enlisted into the British ruling class: Theo always accounted this the happiest day of her life.