A year ago, in the drowsy Vicarage garden

We talked of politics . . .

from ‘To a Communist Friend’, Frank’s epitaph for Anthony Carritt, December 1937

Frank, echoing his mother, accounted his Winchester time ‘some of the happiest days in my life’ and when required one family Christmas to sing one of its school songs – ‘Dulce Domum’ – fought back tears. His housemaster Monty Wright sent Theo in 1933 a vignette of his appearance on arrival: ‘[Frank] . . . throws his head & limbs about & blurts out remarks with an engaging but unusual simplicity. But we are used to odd people in College [as the scholars’ house is known], and his seems a very likeable kind of oddness.’ At Winchester Frank discovered clowning and the ability to make people laugh – exaggerating his ungainliness to excuse his brilliance, sometimes deploying his brilliance to pardon his lack of coordination. Frank learned how to secure affection. He gained popularity through imaginative obscenities, of which one very mild one survives. Once when a Jewish contemporary ran 220 yards fast, Frank was roundly told off for shouting from the touchline, ‘Well buttocked, Hebrew!’ Such clowning underlay Wright’s warning one year later ‘not in any way [to] trade upon the fact that he is “odd” or mistake notoriety for distinction’.

Since these years had a profound impact on him, it is striking to hear Frank’s troop commander in March 1940 echoing this 1933 judgement: ‘A very big man who sometimes seems to have little control over either the movements of his body or the expression of his thoughts.’ Frank had then just got into a ‘catastrophic row’ after drawing ‘cats all over some official report I’d filled out, thinking it was finished with’. Cat-faces decorate Thompson family letters, even on occasion Theo’s – an apt emblem of privacy and independent-mindedness. If Frank courted popularity, there was also an attractive streak within him of devil-may-care nonchalance, unconventionality, a cat-like ability to find his own direction.15

In this spirit Frank made fun of the stammering Bible Revision teacher apropos Ur of the Chaldees. Frank asked him mock-innocently to name that place in the corner of the biblical map: ‘Er . . . er . . . UR.’ Wright noted that Frank should learn to confine his frivolity to suitable occasions. His mind constantly active and alert, he had to ‘grow out of baby ways and discipline some of his restless energy’ to realise his excellent promise. Restlessness and frivolity were in evidence when Frank tussled about the lighting of a dorm fire, chipping one of John Dancy’s front teeth and necessitating a replacement.16

College was the medieval religious community of seventy scholars founded by William of Wykeham in 1394, with the longest unbroken history of any school in England and one dedicated to the Virgin Mary, to whose statue over Middle Gate Frank and his peers were expected to doff their hats as they passed. In 1933 its buildings had scarcely changed over nearly 600 years. Upstairs chambers or dormitories were partly lit by candlelight. Within the huge stones of the four-foot-thick walls, the great Seventh Chamber seemed to stretch upwards into limitless darkness as electric lightbulbs hung down thirty feet from the smoke-blackened ceilings. In a vast fireplace burned fires lit by bundles of twigs named, after a woodsman, ‘Bill Brighters’. Here, at first, all seventy scholars were taught, among walls with marble tablets recording the names of previous scholars over the centuries. Within these great cool rooms it is said that a 1985 snowman lasted indoors for nearly a week. Present scholars sat in ‘toyes’ – partitioned cubicles with very dimly lit (albeit by electricity) working surfaces and bookshelves smelling of ancient polish – wearing a black gown of medieval design with puffed-out sleeves over a waistcoat and pinstripe trousers, together with black ties and straw boaters (‘bashers’) on weekdays, on Sundays stiff wing-collars, white bow ties and black top hats.

There were no boys at Winchester – all, from arrival, were called men. Each was examined on his Notions book, a pamphlet perhaps thirty pages long, bound in dark-blue paper, listing the many odd turns of phrase and tradition the school had accumulated since the foundation (for example, ‘to thoke’: to be idle). Insider jokes abounded. In the middle of Chamber Court, where scholars lived, were two drains for rainwater. Each drain was called Hell and the stone runnels leading to them were called Good Resolutions. The most remote of the several separate chambers in which they lived and worked by day was called Thule. In the middle of the east wall of Chamber Court was a drinking fountain called Moab (from the psalm: ‘Moab is my washpot; and over Edom will I cast out my shoe’), so of course there was also a shoe closet called Edom. Here was a private code designed to repel outsiders.

Winchester could help anglicise you and render you acceptable. Frank’s contemporary the half-Prussian Wolfgang von Blumenthal later changed his name to Charles Arnold-Baker, while the Jewish Seymour Schlesinger, whose father was chairman of the merchant bank Keyser Ullmann and whose long-established family did not know where in central Europe they originated, changed his name in 1942 to Spencer in case he got taken as a prisoner of war. Schlesinger – known at Winchester as ‘The Hebe’, short for Hebrew – experienced some isolation. He behaved on arrival to Frank and others in a way he himself thought ‘spikey’; Frank was unusual in claiming him as ‘My very dear friend’. Such an appellation evinced Frank’s freedom and his warmth of heart. In one 1938 letter Frank addressed his boon companion Tony Forster as ‘My beloved Antony’. They walked arm in arm around cloisters in the evenings, a habit encouraged and known as ‘tolling’. They were not lovers, and quiet, gentle, genial Forster was seen by others as an also-ran, a planet revolving around Frank-as-the-star. Frank, vibrant and imposing, made friends more easily than did his brother.

Two years after Frank went up to Winchester Theo referred to him in his absence as ‘a decent chap’. EP answered fervently and with what his mother recognised as – for him – an unusual display of emotion, ‘He’s more than that.’ The boys, so different, were none the less devoted to one another. Edward hated his sporting successes being used to humiliate Frank and generously forgave Frank’s intellectual successes being used as a whip for his own back.

Edward minded never getting into the top form at the Dragon School where, his mother chillingly observed to EJ, the masters were ‘far from despairing’ of him. ‘We can’t expect him to be as book-brilliant as Frank – and he doesn’t work badly, as a rule. He has his points and we don’t want to break his spirit as we were in danger of breaking Frank’s. Frank was at times, for his age, absurdly patient, apologetic and philosophical, don’t you remember?’ They had, Theo recorded, presumably out of misplaced puritanism, failed to praise Frank sufficiently.

EP concurred with Theo’s judgement in 1926 that ‘nervous trouble’ contributed to the impetigo he first suffered then, a contagious skin complaint recurring over twenty years. Awaiting posting to North Africa he was in March 1943 in hospital with impetigo, the blisters on his face covered in purple iodine; and two years later in March 1945, after the stress of the battle of Monte Cassino and the subsequent liberation of Florence and waiting to be demobbed, this old ailment brought him back to hospital in Tuscany. The comical ad for a clear complexion EJ glued on to one October 1940 letter is intended to cheer EP up: ‘Use Pendle Creams17 faithfully and your skin, like Lady Normanton’s, will look smoother, clearer, lovelier than it ever did before – and with less trouble on your part.’

Theo knew that she had mythical standards of perfection; others saw her as too controlling. How far did her non-stop, bossy, detailed commands, rebukes, injunctions and corrections contribute to her children’s nervous tension? Her letters often compare her two sons invidiously, rarely to EP’s advantage. He was, he later agreed, the ‘duffer’ of the family, not least to himself.

He grew up considering himself – like Winnie-the-Pooh – a Bear of Very Little Brain. Although he was his father’s favourite son, this did not stop EJ colluding in Theo’s lifelong campaign for their younger son’s betterment, once at a Retford Christmas shocking the Pilkington-Rogers family – the daughter Barbara feared her Thompson cousins, finding them intimidatingly intelligent – by publicly calling young EP a fool. It is unsurprising if his strongly left-leaning handwriting suggested a lack of confidence.

Theo found EP self-satisfied, unserious and unsocialised, and lacking Frank’s great talent for friendship. In September 1936, EJ wrote shrewdly to EP, then applying to public school, ‘Remember, this year is of tremendous importance. I am sure you have plenty of brains, if you were not such a slack little beggar. No, it isn’t exactly that; only a slowness to “react”.’ Probably criticism made EP retreat into his shell. In November 1938 EJ issued the barbed remark that on a skiing holiday in Val d’Isère EP might learn some French ‘if you care to take the trouble’. But EP had none of Frank’s love of and ease with languages. In July 1939 EJ advised, ‘Look up the spelling of repetition,’ quipping heavy-handedly in 1941 about EP’s misspellings of ‘meat’ for meet, ‘ake’ for ache, and during EP’s first year at Cambridge was facetious about his writing ‘Desert spoons and medecine [sic]’. As late as April 1944 EP started a letter, ‘I don’t think I’ve wrote you since I changed my address.’ Ability to master grammar and spelling does not necessarily equate with intelligence, something his parents never grasped. EJ once described EP’s letters with the damning word for a Thompson: ‘Adequate’.

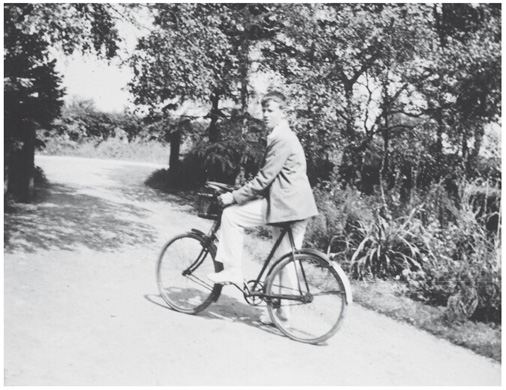

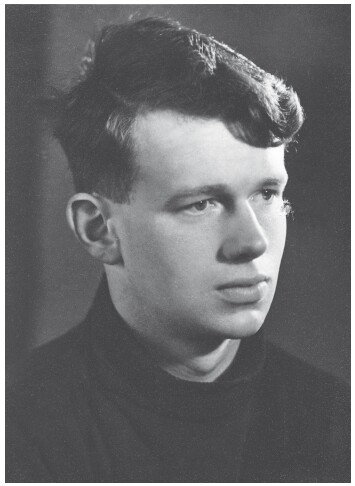

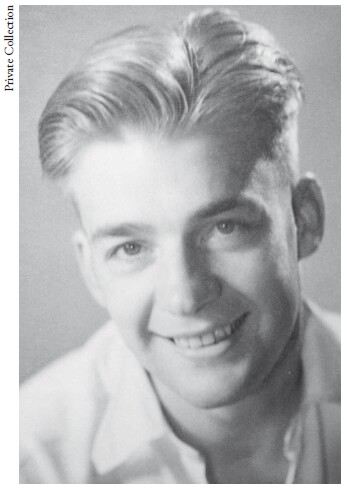

EP, c. 1940.

All four Thompsons regarded themselves as writers in the making and read and commented on each other’s poems, and one of the last times they were together (Alfriston in May 1940) argued fiercely about poetry. It was thus also a natural Thompson habit to appraise one another’s style. As the Count de Buffon put the matter: ‘The style is the man’; so in evaluating one another’s habits of expression the Thompsons were always criticising character too. Theo in February 1938 started by praising EP’s school essay and the brevity and terseness of his letters, noting that he is not – unlike her – wordy: perhaps her verbosity resulted from fear of not being listened to? But her praise was often prelude to a bruising and she moves on swiftly to attack him for pomposity. Some daft comments on her part follow.

EP’s use of such inoffensive words as ‘derive’, ‘erect’ (for build) and ‘respite’ reminds Theo of early Victorian essayists. To cure him she proposes that he read some really modern writer like Max Beerbohm (born in 1872) or Aldous Huxley (born 1892), commending Thackeray (1811–63) and Gibbon (1737–94) as well. True, she also extols Cyril Connolly, Auden and Isherwood’s 1936 play The Ascent of F6, Auden’s recent poem Spain and Hemingway, whose subjects are ‘pretty crude & beastly, but his bare plain style is currently influential’.18 She disapproves of Latinish words like ‘despite’ and recommends instead a future regimen of words like ‘baste, morticed, laced, knit, sown, sprung, larded and furrowed’. One boggles at the Mrs Malaprop-like work of art that combining Theo’s preferred words might elicit. Edward’s essays, she adjures, ought to sound like him; yet her appeal itself sounds artificial.

During EP’s final year at school, EJ cut out and glued on to the top of a letter to him another ad, headed ‘DOES YOUR ENGLISH EMBARRASS YOU?’ Then, in successive smaller strips, ‘Are you content with the way you speak and write? Are you sure that you are not making mistakes that cause people to underrate you?’, and at the bottom, ‘Many ambitious people are handicapped in this way; they cannot depend upon their English not “letting them down”.’

EJ’s intention was at least half humorous, and father and son had on the whole an excellent understanding. But both parents agreed that schoolboy EP had a habit infuriating to Theo of using words with a special top-spin or meaning of his own. EJ addressed this directly in 1940: ‘People have complained that you are a terrible sea-lawyer – that you force words & phrases to carry your own meaning and – yes, you have a rude manner on occasion.’ A ‘sea-lawyer’ is someone who attempts to shirk responsibility or blame through trivial technicalities or, alternatively, questions all orders and rules.

Both boys rebelled against the values of their parents, most obviously in joining the CP. But their rebellions differed. Even at the age of thirteen Frank picks up all references in his parents’ letters, saying something to let them know that they have been carefully listened to. Through attending closely to their concerns, he occasionally shook free of his parents, exercising independent choices of his own. This knack came less easily to Edward.

In a sense both bear the marks of Theo’s and EJ’s conflicts – Frank condemned to the role of victim doomed to understand everyone in every dispute, EP to playing a different kind of victim who does not. Indeed he acquired an unfortunate and lasting habit of misreading others on occasion.

EP resented Winchester for dividing the brothers. It had the highest and most rigorous classical training of any English school, a training Frank loved, internalised and made his own. EP by contrast attended Kingswood, a school ‘with no elite pretensions and no classical ambitions’. He disliked Winchester’s self-satisfied sense of its own excellence, its cult of eccentricity and affectations, and the ruling-class manners and arrogance of one or two of Frank’s friends. Frank too could communicate an unconscious sense of insidership, as when, skiing in France, he accurately identified by manner and accent alone a fellow public schoolboy as having attended Charterhouse. Did EP and Frank inhabit different social classes?

In fact Winchester scholars’ sense of entitlement was as much intellectual as social. Some scholars paid nothing, not even extras, a source of notable tension between scholars and commoners. College was still notionally for the poor, and considerable school wealth dating from the compulsory sale of land under Cardinal Wolsey subsidised scholars’ education; Frank’s parents paid only thirty guineas per year inclusive, for board, tuition and lodging combined. Considering that commoners paid £200 (from 1937, £220), this was a significant remission. Yet if poverty did not exclude you, this was middle- or upper-class poverty: even to be considered for Winchester you needed to have attended a prep school teaching you Greek. That Frank’s education cost their hard-pressed parents a good deal less than Edward’s no doubt added to his popularity.

Edward – by contrast – was sent to Kingswood, his father’s school, where the sons of laymen were charged £115. Why was he sent there? EJ had after all felt cheated at Kingswood of the rounded education major public schools afforded; and Theo once remarked that Edward’s teeth began to go bad when he went to ‘that dreadful Methodist school’, adding brightly and foolishly, ‘If only we had sent him to a nice ordinary school like Eton or Rugby.’ The fact of the matter seems to be that, wrongly believing Edward too dim to get into the foremost schools, Kingswood appeared to his parents a safe bet. He none the less won an exhibition and found to his surprise and pleasure that he was on arrival nearly two years ahead of his year in Latin and Greek; he matriculated at fourteen, one year later joining the sixth form.

EP would later provide a terrifying account of Kingswood around 1748 when Wesley’s ferocious, cruel-to-be-kind intentions in founding it were all too evident; he famously castigated Methodism as ‘a ritualized form of psychic masturbation’. Since EP had received little religious education before, Kingswood probably constituted a shock. The sons of lay people had first been admitted in 1922, but around 50 per cent of boys were still sons of ministers and missionaries, the remainder children of ‘honest hard-working poor tradesmen’. While Winchester cultivated leadership and turned out company directors, dons and MPs, Kingswood produced accountants, lower-ranking civil servants, scientists. There was a strong emphasis on serving the community, and religion’s more puritan and repressive forms were important – the world’s problems discussed in religious terms. Methodism was ‘all pervasive’ and the headmaster given to one-to-one homilies.

On the outbreak of war the school was evacuated to Uppingham in the East Midlands. Kingswood’s historian sagely records that the headmasters of Uppingham and Kingswood ‘wisely’ chose not to amalgamate schools ‘so different in size, clientele and ethos’ but preferred ‘to co-exist’. This meant that although they lived cheek by jowl they were almost totally separate. For four whole years, and despite wartime ‘solidarity’, most boys never addressed one word to their peers in the other school.

Uppingham – the senior, solidly Anglican foundation – evidently feared pollution. In his seminal history The Making of the English Working Class (1963) EP presented Methodists – beginning under the aegis of the Church of England – partly as cowardly lickspittles urging appeasement of the rich and powerful. Kingswood was certainly the more ‘aspirational’ of the two schools, with which Uppingham refused to play rugby matches at 1st XV level: EP wrote that they feared losing caste if beaten by the socially ‘inferior’ school. George Orwell noted the many small yet intractable gradations of the British class system, and apartheid between different parts of the great British middle class would interest EP the future historian. He made no Uppingham friends.

After a brief, unserious flirtation with the Oxford Group (caricatured as a ‘Salvation Army for snobs’ and supplying one Kingswood housemaster) EP campaigned first for the inclusion within chapel services of Blake, Whitman and William Saroyan, later forming an actively anti-chapel committee that wanted church attendance made voluntary. EP considerably upset the partly liberal, one-legged head Dr A. B. Sackett (he had lost the other leg at Gallipoli) by demythologising Christianity to the History Society, citing both Karl Marx and Sir James Frazer’s The Golden Bough.

Kingswood, for all that he deplored about it, gave him friendships with other radically minded alumni that mattered for life: the future publisher Adrian Beckett, the poet-academic Geoffrey Matthews and the writer Arnold Rattenbury, two years older, with whom EP half-unhappily fell in love and who exercised a profound influence. EP was reduced from the rank of prefect for smoking or for his Marxist politics or both. He, Rattenbury and Matthews, who had all joined the CP, began selling the Party’s newspaper the Daily Worker in the dormitory. When they tried to join the Young Communist League their letters of application were intercepted and they were interviewed by the police in the headmaster’s study, an event that did little to discourage revolutionary fervour.

EP felt mixed about Kingswood. There were two flourishing literary societies and a library rich in modern books; there were also annual plays, and in one religious drama he acted the Archangel Michael. He was always very keen on acting. And he liked the school’s virility, variety and independent-mindedness. Then, in 1940, a year when Theo encouraged him to think of attending RADA to become an actor, an essay of Christopher Hill’s on the Levellers – the political movement during the English Civil Wars which emphasised popular sovereignty, extension of suffrage and equality before the law – electrified him. Thus was born in him that famous urge to ‘rescue the ordinary person from the vast condescension of posterity’ that would famously inspire his life-work. Condescension and disempowerment were topics his upbringing had schooled him in, as were exclusion and unfairness. He was sensitive to slights to others as well as to himself.

When EP was at Cambridge EJ observed to him that ‘your inherited danger is to be a bit of a prig’ – someone who parades moral superiority to compensate for the want of other kinds of excellence. EP agreed: ‘I have seen Kingswood turn out prigs’; and he acknowledged his own ‘annoyingly serious attitude to life plus certain puritan strains’. His drive was moralising, demotic, even Methodistical. One of Frank’s Winchester friends, borrowing terms made famous by Matthew Arnold, contrasted EP’s ‘Hebraism’ with Frank’s ‘sweetness and light’. Frank’s apprehension of the world, EP noted in his turn, was more aesthetic, EP’s own more earnest and moralistic.19

Boys about to leave Kingswood spent hours in discussion with the school chaplain. The contrast with Winchester is striking. Donald McLachlan, who taught Frank Divinity, was a free-thinker, and gave out Plato and even Voltaire. Unsurprisingly, in a school debate shortly before he left Winchester Frank claimed that he was no puritan and lacked any form of ‘non-conformist conscience’.

What EP termed Winchester ‘eccentricities and affectations’ are plain. Its dandy delinquencies included staying up late eating ‘exquisite anchovy toast and scrambled eggs which challenged Boulestin’, ending up at half-past two with the gramophone playing Paul Robeson’s ‘Little Man, You’ve Had a Busy Day’ (‘You’ve been playin’ soldiers, the battle has been won / The enemy is out of sight / Come along there soldier, put away your gun / The war is over for tonight’). Or absconding to the library roof to pipe-smoke Three Nuns or Classic Curly Cut. Frank noted on leaving ‘The numerous and glorious societies’, formed by himself and his friends – ‘[the] brown shoe soc, pyjama top soc, evening trouser soc . . . Self-Expression Soc with its blaze of red shirts, yellow pullovers, lumber jackets, overcoats, umbrellas, berets, glassless spectacles & odd stockings’. Together with some friends, Frank also formed the Philology Society whose members – it was unfairly claimed – liked to exchange insults and obscenities in obscure languages or scripts such as Glagolitic.20 Winchester dandyism could appear irresponsible, exclusive and conceited, and make Frank sound like a brainy member of the Brideshead set. But he also learned Russian at the school.

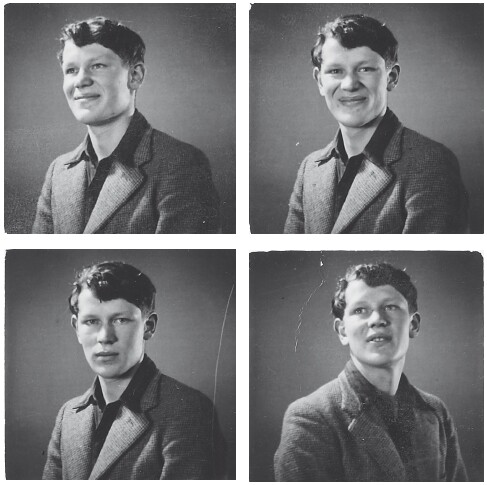

Frank ‘absconding to the library roof’.

Edward once argued that Frank was strongly influenced by the ‘rather easy cynical philosophy of Winchester . . . together with its lazy all-embracing humanism’. Frank agreed. In 1943 he argued that levity and superficial cynicism marked Wykehamists (as ex-pupils are known) for life. While the school paid lip service to civic duty, and he could imagine a Wykehamist willing to die so that a public building survived, he believed that, despite such aestheticism, the school inculcated ‘next to no idealism but a strong intolerance of folly’ instead. He joked that when he started drinking less in 1943, this was not from moral principle – he was ‘too loyal a Wykehamist to be guilty of harbouring a conviction’ – but from disinclination. Its whole method made one into a private person. Winchester was therefore a typical major public school, which he thought turned out officers frivolous to the point of nihilism.

Yet Frank retained the irritating habit of liking more people than Edward, so that when EP complained of the self-conceit of an Old Harrovian in his regiment, Frank remonstrated, ‘It’s a mistake to hate people because of their class.’ As for Frank, he has only generous things to say of his younger brother, accounting Edward in 1941 ‘what I would like to have been – an honest, warm-hearted witty & imaginative Englishman with no illusions. He writes poetry with signs of genius – at 17.’

In the autumn of 1936 Frank underwent a crisis. His friend the future historian M. R. D. Foot had been confirmed into the Church of England by the Bishop of Winchester, Cyril Garbett. Should Frank follow? In the event Frank followed his own star and was never confirmed. But on 24 October that year he and a visiting Theo walked down College Street, she unaware since it was dark that he was silently choking back sobs, his cheeks tear-stained. Theo remonstrated, thinking him bored. ‘She’s very unhappy about me.’ What good would confirmation do? It would make him ten times more unhappy. His diary records self-flagellation, refusing to entertain ‘thoughts of suicide . . . From what a nice family I come, to think how nice I really am myself, and how foully I behave at school. I am noisy, bumptious, foul-mouthed and foul-minded. It is not my life at home that is hypocrisy (even there I’m often vile) it is in the life here that I am true to myself. It is depressing.’ Contemporaries recalled how his ribaldries kept everyone amused. He was growing up so big and uncoordinated he was nicknamed ‘Ban’ for Caliban.

A prefect penned comments on the other scholars with a very Wykehamical mixture of urbanity and malice (never dreaming that biographers would later root among them). Peter Wiles, brilliant, short and waspish, a future Fellow of All Souls and Sovietologist at the London School of Economics, recorded Frank as the Chamber Poet. ‘Hates to put his feelings into words: hence his only safety valve is poetry & that not very effective . . . even after his most brilliant eruptions [Frank] remains a mass of unrelieved uncomfortableness.’

Poetry and clowning were safety-valves. Meanwhile Wiles goes on cattily to describe Frank’s physical clumsiness as irritating ‘even though partly not affected’, and he saw that his rumbustiousness, being partly a pose, concealed as much as it put on display. It was later observed that, if Frank didn’t like or trust you, he did not break his reserve. Wiles sketches Frank’s insomnia, constipation, tendency to embarrassment, prudishness, sleepiness, ‘abominable’ cleverness, his mix of cynicism, Falstaffian joie de vivre and high moral earnestness.

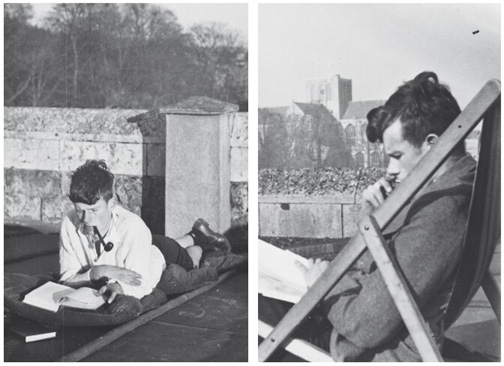

Frank, 1936.

The painful quarrel within Frank between high-mindedness and low motives – common among adolescents – is here shrewdly caught. It fuelled his confirmation crisis, about which he wrote to EJ, then on a four-month trip to India. EJ replied memorably from Calcutta on 2 November 1936. He had lost his own faith, and knew that most boys get confirmed automatically, meaning little by it. Because EJ’s own difficulties and sufferings have arisen from the ‘unconventionality’ of his upbringing, he wants his sons not to repeat these mistakes. He honours Frank’s scruples but undercuts the exaggerated sense of responsibility that underlies them. Frank had expressed to his father a concern that he might one day become a Catholic. EJ, after dismissing this point, continues:

I will tell you what I believe. Nothing matters except character, which as the years pass is its own increasing reward. There is a mind in the universe, some kind of personality that seeks to get into touch with the spirit of man . . . The ‘worship’ sought is not adoration of some supermortal sultan, but the spontaneous rushing-out of our wills into selfless action. And here again comes in one of those truths by which we are saved. ‘He that saveth his soul shall lose it, and he that loseth his soul shall save it’. These swiftly passing earth-days are ours, not to develop an aggressive ‘personality’, a noisy individuality – but to lose what we are, to get rid of ourselves so that we may rise into a self that is greater & purer & nobler than we can ever imagine.

We have got to lose our soul, our self. Why not? There is a nobler soul waiting to be ours! It is hard to explain but it happened – that men and women do get gripped by something that fills their lives with personal communion, & gives them a sense of destiny which makes them fearless.

The credo Frank lived and died by owed much to his father’s alarming courage, inspired by his Christian belief and Boy’s Own-like bravado. One should, EJ believed, ‘face the music’ as he had himself done during important crises. He gives an example from the Mesopotamian campaign in 1917. After his ‘very dearly beloved brother’ was killed, a period of desolation and physical weariness followed. In April came heavy fighting, which at first appalled him. Then, suddenly, on a day of grim battle something ‘took hold of’ him, and ‘without even knowing what fear was’ he won a reputation with brave men for bravery. He does not mention gaining the Military Cross; Frank would take this as understood. Despite being very ill afterwards and lying sick in Basra, EJ had all that summer lived in ‘a serenity of destiny and fearlessness. It was a wonderful experience . . .’

EJ also wrote about how periodically an English hero redeems his country’s bad faith. He had in mind Byron, who ‘died encouraging the Greeks still firing at their Turkish oppressors’. He asked rhetorically, ‘Can one man today achieve anything that matters by a gesture?’ – a provocative question to the impressionable Frank. No doubt the sacrifice EJ intended was less extreme than the one Frank, in the event, found himself making. During the next war Frank would echo his father’s beliefs in the heroic virtues of selfless action, of nobly losing one’s soul in order to gain it, and inhabit his own serenity of destiny and fearlessness.

Winchester had many ways of endorsing these codes of chivalry and gallantry. Some streets away from College was Winchester Castle Great Hall, in which hung the eighteen-foot Arthurian Round Table created around 1290 in solid oak for Edward I, designed for royal tournaments and decorated with the names of twenty-four Arthurian Knights including Sir Galahad, Sir Gawain and Sir Lancelot. Then in June 1934 a College library copy of Malory’s Morte d’Arthur (later identified as the book used by its first printer William Caxton) was discovered, and scholars were set Malory as a topic for the English prize. Malory’s knightly sentiment and the horrible end meted out to villains captivated Frank and contributed to his winning the Gillespie Prize in 1935. He won many other prizes – for poetry, Latin verse and archaeology. Scholars were intensely competitive. Winning prizes mattered.

Frank would later claim that he was converted to belief in Communism by Iris Murdoch in the second week of March 1939. Yet among the leading questions about confirmation that he put to Theo in 1936 was ‘Suppose I should want to be a Communist after a few years?’ Why might Frank have predicted this?

First there is the case of John Hasted’s conversion. Frank in 1933 took Hasted, whose widower father had fought with EJ in Mesopotamia, under his wing. Hasted acknowledges that after having first thought Frank ‘rather an ass’ he later changed his view. M. R. D. Foot, closely observing this friendship, believes Frank influenced Hasted while both were still at Winchester to become a libertarian Bolshevik. Hasted, whose political commitment connected with his love of popular song, later became Professor of Physics at Birkbeck. He did much to foster folk music, and stayed on in the CP after 1956, until he died in 2002.

Then there was the mock election in College to coincide with the 1935 General Election, when Robert Conquest – later pioneer unmasker of Stalin’s Great Terror – stood as a Communist candidate. Although the Conservatives won, the CP gained an astonishing fifty votes. Agitprop featured, as did red scarves, clenched-fist salutes and cries of ‘Red Front!’ (meaning Popular Front) ringing round the old school building, all tokens of the temper of the times. Only two years before, a school election had been cancelled when two young gentlemen turned up wearing red ties. Conquest joined the CP for one year on leaving Winchester in 1937. During this 1935 mock election Frank deputised for Conquest and the CP and, when asked why he had shaved off his eyebrows, Frank said he hoped they would grow back bushy like Uncle Joe’s. (They failed to do so, and meanwhile he bought an eyebrow pencil to make good the deficit.)

There were also radical left-wing teachers like Eric Emmet, by whom Frank was taught maths, and Donald McLachlan, who had been The Times’s man in Warsaw. In Berlin the night of the Reichstag fire in February 1933 McLachlan wrote a dispatch so good that he was summoned to London to write leaders. (Frank and M. R. D. Foot had read the Times reports of the Dimitrov trial to each other that autumn. Dimitrov would play a part in Frank’s 1944 downfall.)21 Bored with journalism, McLachlan arrived in Winchester in 1936 to teach Russian, German and current affairs. He was a stimulating teacher, encouraging his pupils to think for themselves, and sharing with them a first-hand knowledge of European personalities. When the Spanish Civil War started in July 1936, he hung a map of Spain in class with the battle fronts marked daily so as to keep up to date. Frank followed the Times reports every morning: the pro-Franco stance of Spanish Catholics soon helped wean him from a flirtation with Anglo-Catholicism.

Another influence was the Carritts, close neighbours and friends. All five Carritt boys like their mother were in the CP, even young Brian at Eton where he raised money for twenty hunger marchers to be fed at Windsor and invited leading CP theorist Palme Dutt to speak. His elder brothers, suspicious of his choice of school, gave Brian an annual interrogation. ‘Shades of Karl Marx! A communist in a top hat!’ quipped Frank. ‘What will Gabriel have to say?’

What Gabriel Carritt – who proletarianised his name to Bill – said was that left-wing politics seemed an absolute answer for his psychological problems. Joining the CP for your own needs was, Bill thought, nothing to be ashamed of: for the Carritts revolutionary social change was connected with personal growth. Bill’s own problems were completely buried under this energy and enthusiasm, the 1930s being the ‘most marvellous time to [be] alive . . . a happy time among all those friends! . . . We believed . . . we could change history.’ Among Frank’s 1937 poems is one dialoguing with Brian, another with Anthony Carritt, with almost identical titles.

Lines to a Communist Friend

Here, in the tranquil fragrance of the honeysuckle,

The gentle, soothing velvet of the foxgloves,

The cuckoo’s drowsy laugh, – I thought of you,

The ever-whirring dynamos of your will,

Body and brain one swift, harmonious strength,

Flashing like polished steel to rid the world

Of all its gross unfairness. – But the grossest

Unfairness of it all is that, tomorrow,

When both of us are gone, my sloth, your energy,

The world will still be cruelly perverse.

– Why not enjoy the foxgloves while they last?

July 1937

‘Body and brain one . . . strength’ mirrors Brian’s famed sporting prowess, a synchronisation now dedicated to his egalitarian politics. The poem weighs this politics against fleeting beauty, sceptical about the chance of ameliorating life’s cruelties. Frank had written in his diary of the sense of futility College could instil: ‘the old grey walls frown down & say, “We know. It is not worthwhile. Before you, there were many others who wrote poems here. They have all gone, some to oblivion, some to glory, but the world runs on without them.”’ Thus he pits the fugitive foxgloves of English pastoral elegy, endorsed by Winchester, against activism.

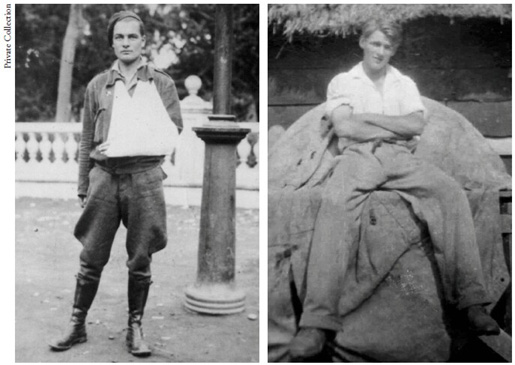

Brian Carritt, c. 1938.

The theme of being a trapped, conscience-ridden spectator recurs in another July 1937 poem, ‘Suave Mari Magno’, its title a tag from Lucretius meaning that it is sweet, during a tempest, to witness from the safety of landfall the perils of those at sea: that is, the jeopardy entailed by those committed persons fighting for and against Fascism, ready ‘to perish, even to kill’. Within the frame of a love letter Frank enquires into the political passion that would inspire three Carritts to go to Spain. The poet prays for their faith and inspiration. The ‘my darling’ of the poem need not refer to a given woman, but other poems do invoke a specific, unnamed beloved who might be Tony Forster’s ‘wacky’ sister Felicity/Fifi or Robert Graves’s daughter Catherine Nicholson, green-eyed, red-haired, to whom Frank was attracted, and whom Theo at some point hoped he might marry.

At the start of the Spanish war Gabriel Carritt together with the secretary of the Young Communist League walked over the Pyrenees to find out what aid was needed. He co-founded the British Youth Foodship Committee, collecting food and clothing for the Republic. When Gabriel returned, two of his brothers set out. His middle brother Noel arrived in Albacete in December 1936, having informed their parents by means of a note scribbled on the back of an old cheque sent as he left via Victoria that he was joining the 2,700 Britons in the International Brigades: ‘Darling Mother and Father, I hope you’re not too furious with me . . . sorry not to have seen you but I thought you’d probably try and stop me.’ A teacher in Sheffield, he gave his school no notice. Anthony joined him. Their mother and Brian collected for Spanish Medical Aid in Oxford and at Eton respectively, Brian also raising £200 to commemorate an Old Boy and friend (Lewis Clive) killed with the Brigades.

Anthony and Noel trained at Madrigueras. In February 1937 at the battle of Jarama an enemy bullet hitting his rifle broke Noel’s wrist; later as an ambulance driver during the battle for Brunete he was wounded in the head. Here Noel’s brother Anthony, two years older than him, was also badly wounded in an air attack; Virginia Woolf’s nephew Julian Bell was killed in the same battle. Noel scoured hospitals and field stations exhaustively before accepting that Anthony must be dead.

It would be surprising, given his closeness to Gabriel and Brian, if Frank did not learn of one trigger for Anthony’s Spanish odyssey: distress at discovering his parentage. He had recently asked Amy, the Carritt family housekeeper, of a photo of Arthur Darbyshire, his mother’s lover who died in France during the Great War: ‘Is this bastard my father?’ Amy – fond of Anthony – could only admit that she believed he was. This recalls Gabriel’s view that Communism helped his generation solve psychological difficulties, of which Anthony’s illegitimacy was a case in point. His family offers further case histories: Penelope committed suicide, Betty rebelled, Michael in the Indian Civil Service cooperated clandestinely with Indian nationalists, Noel often fell into apathy and isolation.

Noel (left, in Spain) and Anthony (right) Carritt, both 1937.

In December 1937 Frank addressed Anthony’s ghost in a second poem entitled ‘To a Communist Friend’, a sonnet whose careful half-rhymes underscore the seriousness of its writer’s engagement with its themes.

A year ago, in the drowsy Vicarage garden,

We talked of politics; you and your tawny hair

Flamboyant, flaunting your red tie, unburden’d

Your burning heart of the dirge we always hear –

The rich triumphant and the poor oppress’d.

And I laugh’d, seeing, I thought, an example

Of vague ideals, not tried, but taken, on trust,

That would not stand the test. It sounded all too simple.

A year has pass’d; and now, where harsh winds rend

The street’s last shred of comfort, – past the dread

Of bomb or gunfire, rigid on the ground

Of some cold stinking alley near Madrid,

Your mangled body festers, – an example

Of something tougher. – Yet it still sounds all too simple.

Anthony impressed Frank by putting his ideals to the test, not merely of action, but of martyrdom. The poem’s painful dispute between scepticism and belief no longer recalls an historical disagreement between friends but a conflict within the present moment that haunts Frank, experiencing the urgent summons of the new politics: ‘The rich triumphant and the poor oppress’d’. Anthony, in the words of this poem, had indeed ‘stood the test’. Frank later wrote that ‘Spain was so real, that it hurt.’

A Winchester contemporary of Frank’s, the noted physicist Freeman Dyson, opposed Frank’s martyrdom in the Balkans to the Allied fire-bombing of Dresden, known for its pre-war beauty as Florence-on-the-Elbe. News of both would break early in 1945. Dyson deplored the obscene horror and waste of Dresden’s destruction as wicked and counter-productive; he spent his war in Bomber Command, involved in a technological war at a distance that seemed to him corrupt and futile. By contrast Dyson envied and revered Frank as someone fighting for a ‘clean’ cause, in hand-to-hand combat.

Dyson’s admiration for Frank started at their first meeting in September 1936 when he arrived in College, three years younger than Frank, another scholar sharing the same Chamber. There was no privacy but a constant and cheerful uproar with verbal and physical battles raging unpredictably. Frank was the largest, loudest, most uninhibited and most brilliant of Dyson’s new schoolfellows. He wrote: ‘I learned from him more than I learned from anybody else at that school, even though he may have been scarcely aware of my existence.’ He recalls Frank coming striding into the room after a weekend away, singing, ‘She’s got . . . what it takes’.22 This set him apart from the majority in their cloistered all-male society.

The reasons for Dyson’s admiration were many. First, Frank loved learning new languages with a passion, especially at this point Russian, which he and his friends, together with one master, decided after a talk by Bernard Pares to put most energy into learning. They had lessons twice a week, and Frank was before long translating Gusyev and Mayakovsky.

Then Frank, sensitive enough to feel the enchantment of Winchester and – to take a trivial example – to address his women-friends after leaving the school as ‘Madonna’, was also strong enough to react against it. In June 1935 he had called the Middle Ages ‘one of the best ages the world has ever had . . . the most interesting. Such a peculiar mixture of learning, superstition, cruelty and beauty.’ In 1943 by contrast he wrote that ‘the culture one imbibed at Winchester was too nostalgic. Amid those old buildings and under those graceful lime trees it was easy to give one’s heart to the Middle Ages and believe that the world had lost its manhood along with Abelard. One fell in love with the beauty of the past, and there was no dialectician there to explain that the glory of the past was its triumph over the age that came before it; that Abelard was great because he was a revolutionary.’

At fifteen Frank had already won the title of College Poet, was a connoisseur of Latin and Greek literature, and was interested in Silver (late) Latin and soon modern Greek too. He was more deeply concerned than the rest of them with the big world outside: with the civil war then raging in Spain, with the world war he saw coming. From him Dyson caught his first inkling of the great moral questions of war and peace which were to dominate all their lives thereafter. Dyson knew what had happened to the English boys who were fifteen at the start of the First World War and arrived in the trenches in 1917 and 1918. M. R. D. Foot also wrote: ‘In all probability I had not many years to live.’

Listening to Frank talk, Dyson learned that there was no way rightly to grasp these great questions except through poetry. For him poetry was no mere intellectual amusement. Poetry was man’s best effort through the ages to distil some wisdom from the inarticulate depths of his soul: there was no deeper way to grasp the great questions of the day. He envied Frank, fighting ‘a poet’s war’ – and meeting (though Dyson never exactly says so) a poet’s death.

Frank could no more live without poetry than could Dyson without mathematics, and Dyson quotes Frank’s 1940 poem ‘For the Sake of Another Man’s Wife’, which relates Dunkirk to the Trojan Wars: for Frank (Dyson felt) it is natural and obvious that the grief and hatred of these Greeks 3,000 years ago, made immortal by a great poet 700 years later, should mirror and illuminate our own anguish. The essentials of war – the human passion and tragedy – are the same. So he weaves the two together. It is interesting that it was exactly this account of Frank by Dyson that reconciled young Edward – prejudiced against the great public schools – to what Winchester had meant to Frank.

Frank was that rare combination, a soldier-poet and scholar-soldier. The great human problems are for him problems of the individual, not of the mass.

Seated left to right, Frank, David Scott-Malden and Roddy Gow (killed at Arnhem 1944); standing, Hugh T. Morgan (left) and unidentified. Sunday wear, 1937.

On his final night at College evening prayers Frank burst into tears when Loyola’s famous prayer was read (‘Teach us, good Lord . . . to give and not to count the cost, / to fight and not to heed the wounds, / to toil and not to seek for rest, to labour and not to ask for any reward / save that of knowing that we do your will’) and continued weeping (again) through the school song ‘Domum’. He feared he might never again share his lunacy with men so spontaneously inspired. On the library roof after half a pint of sherry afterwards, and while he and his friends reeled about pretending they were being funny, Frank made two resolutions: ‘1) however many women I may go to bed with, never to marry until I meet one with whom I am in poifect [sic: Brooklynese] sympathy, – to whom I can tell all my vices and who will know how to laugh at the same. 2) to leave the world somehow better than I found it. I don’t know how, but I’m buggered if I won’t do it somehow.’ He also recorded that he was a little drunk. High-mindedness, like the writing of poetry, ran in all the Thompsons.