Laughter and sleep were all I loved on earth;

And now I find the latter far the best.

from ‘My Epitaph’, February 1938

Frank, aged seventeen, secured a scholarship at New College, Oxford, to start in the autumn of 1938 to study classics (known as ‘Mods and Greats’) and left Winchester for good in early April. His father would later say that Frank’s taking himself off thus, in the middle of the academic year, was symptomatic of his fatal restlessness. But he passionately wanted to visit Greece. While there he sent home fifty-plus pages he had written ‘in the form of Mass-Observational Diaries’ and he also wrote poems. The contrast between the prose and the poetry is instructive. The last of his Greek poems, ‘The Norman in Exile’, evokes his homesickness: ‘Here in this land of blue, unclouded sky, / This languid land of death, I long for home.’ While this poem is a typical lament exploring melancholy, nostalgia and foreboding, his letters at the same time evoke him ‘laughing himself sick’ in Crete.

Frank had a happy temperament. The low spirits he suffered with jaundice in Hamadan in 1942 are remarkable for being the only time in his life when he sounds genuinely downbeat and unresourceful. Iris Murdoch wrote accurately to Theo in 1941 about his seeming to have ‘a genius for finding all experiences fascinatingly interesting’. He was the least despondent, most effervescent and exuberant of men, his curiosity about the world always on display. Comedy and tragedy are two ways of exploring this curiosity and – increasingly – two halves of one whole. Frank’s prose is happy and given to what John Pendlebury, with whom he excavated on Crete, termed Frank’s ‘puppyish lunacy’, his letters and diaries conveying a comedic delight in life’s details. His verse, by contrast, is sad, his poems enshrining sturdy pessimism and the sense of his generation’s fragility. Poetry is his way of mythologising his real difficulties into a half-pleasurable gloom and melodrama, prose (diarising and letter-writing) his way of obtaining a very different kind of release through clowning.

Had Frank survived the war – he could well have – his poems might have seemed to his older judgement immature, a source of embarrassment to be disowned or forgotten. Since he did not survive, their interest remains as lyrical attempts to negotiate the pain of growing up in a time of exceptionally dramatic public events which they reflect; and they have the gloomy added value – since so many take the form of epitaphs – of appearing prescient, and foretelling his fate.

Death and dying attract immature poets. Keats – whose grave Frank visited in 1938 – in his ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ wards off the anguish he had witnessed five months earlier when his brother died of TB with wishful thinking about an ‘easeful death’ for himself. Tom’s death had not been ‘easeful’ and indeed heralded Keats’s own. Conjuring with the idea of death can be a secret talisman against it happening for real. Keats’s romantic Schwärmerei in the famous lines ‘Now more than ever seems it rich to die / To cease upon the midnight with no pain’ is a prayer for escape from the real suffering all the Keatses underwent, the poet himself soon included. And his marvellous ode is great because it contrives to evoke death and immortality in equipoise, in an intensely moving dramatisation.

Frank, too, flirted with his own Keatsian death-wish. More than his Winchester contemporaries he was – as Freeman Dyson saw – marked by certainty that his generation was to be drastically culled by war. Poetry was, as Dyson understood, his dramatic means to explore and develop this understanding. His first surviving poems date from 1935 and conjure with death. ‘Death of a Dryad’ is mere adolescent emotionalism about transience. ‘Death in the Mines’ is socially and politically aware. ‘Death in the Mountains’ concerns the necessary nobility of courage. ‘Pythagorean Love’ in March 1936 asserts the permanence of love against death, but not yet persuasively.

In ‘War so Jung und Morgenschön’ (‘[He] was so young and lovely as the morning’), written in December 1936, we hear for the first time his own fluent voice. This is not at all modernist: there is little that he wrote that would have surprised W. S. Landor (1775–1864). But he is developing lyrical strength and confidence, expressing the theme with which we most associate him – the strange happiness of those who risk an early death, unsullied by the cares of age. Its first stanza starts:

Spring on his brow – and in his heart was spring:

He left us in the April of his years.

He does not ask for sighing or for tears

Who left when it was still worth lingering . . .

Lawrence Binyon, too old to fight at forty-five and so a spectator when he wrote his ‘Ode of Remembrance’, famously envies the invulnerability of dead soldiers – ‘Age shall not weary them, nor the years contemn . . .’ Frank at sixteen, by contrast, elegises his generation who are to die young while identifying with the insouciance of bravery himself. The title, from Goethe’s ‘Heidenröslein’, showcases his already devout internationalism. His poem titles from German, Latin, Greek, Russian, French and Silver Latin have today the unfortunate effect of distancing Frank. He belongs to that remote age when all gentlemen were presumed to share familiarity with the classical canon, and other languages too. His internationalism was one way of demonstrating anti-Fascism.

That a time is coming when every man’s mettle will be tested is the theme of the ‘Democrat’s Defeat’ (May 1938), with its strangely scanned long third line:

Some will gutter and faint in an hour,

Some will crash at last in the flames

Having blazed for a while on the sky and men’s hearts’ amazement

At the radiance of their fame.

Though the next and last verse asserts that ‘the gulf between glory and silence is minute’, this qualification seems polite, rather than persuasive. The poem reflects EJ’s belief in war dividing the men from the boys.

‘When Lovely Woman Stoops to Folly’ compares a woman friend’s unhappiness on surrendering to a handsome man with a moth burning its wings in a candle:

Last evening, as I sat reading in the twilight,

A moth came whirring in, graceful and velvet-sleek,

Batter’d her soft brown wings against the curtains,

Half-terrified and brush’d against my cheek.

Although purporting to concern the woman friend with whom, together with her sisters, he had been staying, the thought that really inspired the poem was ‘what a shame it wd be if they were all killed in a war’. Without obvious logic, this somehow prompted Frank’s simile of the moth’s singed wings. The connection between the casualties of love and those of war is not self-evident: the apocalyptic fears of the time dictate it.

‘Farewell to Fame’ (spring 1937) is a successful lyric gracefully comparing – in a partly Audenesque way – his soul to an aeroplane that crash-lands. Its use of language is witty, its handling of feeling dexterous:

Stretched out in cool green fields of clover,

Heart beating hard with earth,

I found it was not stars but flowers

Presided at my birth.

All these poems set the personal against the political, aware that public affairs threaten soon to extinguish the personal.

‘On the Extinction of Austria’, a poem written the same month as the Anschluss (March 1938), has the lines:

The time for resistance is past.

Not a cause but an aeon is dead.

An age, not a nation is plunged in the final darkness

Of the storm-cloud’s smothering dread.

For all their immaturity and occasional woodenness, one sees why Frank deserved the title of Chamber Poet. Frank’s death-consciousness played another and paradoxical role: that of intensifying his sense of the preciousness of life. He was to remember the ‘invasion summer’ of 1940 as the most beautiful ever. The sense of jeopardy, which his poems repeatedly explore, always heightened his happiness, like a mountaineer experiencing a rush of elation.

‘My Epitaph’, of February 1938, sketches his extinction in the spirit of a light-hearted epigrammatist, who – it should be noted – invites not grief at his demise but the mirth, if not applause, of future Wykehamists to whom the cloister belongs. Its cheerful and upbeat treatment of the theme of extinction looks forward to his best-known poem, ‘Epitaph for my Friends’.

Here in the sunlit cloister let your mirth

Blend and suffuse my last and sweetest rest.

Laughter and sleep were all I loved on earth;

And now I find the latter far the best.

This jokes about two notable aspects of Frank’s character – his love of fun and his laziness (‘laughter and sleep’) – but above all manifests sprezzatura: that pose of studied carelessness valued as typically patrician since Castiglione wrote The Courtier in the fifteenth century.

Sprezzatura: a form of defensive irony; the ability to disguise what one really feels, thinks and intends behind a mask of apparent reticence and nonchalance. It is brave performance-art, invoking a courage that one might not merely ape in a poem, but live and die by, too, and displaying an easy facility in accomplishing difficult actions which hides the conscious effort that went into them. The difficult action about which Frank nonchalantly teases is dying. He wrote many epitaphs for himself.

Both major structures of feeling – comic and gloomy – Frank inherited from his father. Theo believed that EJ’s County Wicklow great-grandmother gave him that ‘Irish pessimism’ that occasionally disheartened her. But she thought Irishness also the source of the wit and humour he and both their boys shared, leavening the pessimism and making it bearable.

EJ (seated fourth from left ) with Oriel Fellows.

What was Frank’s father EJ, that lifelong outsider, doing in the 1930s? His many attempts to find a more secure position finally bore fruit when a Senior Research Fellowship at Oriel College was founded for him in 1936, and for three years earned him £250 per year. A string of well-reviewed books had also established his name, and Scar Top became a watering hole for writers, liberal dons and Indian nationalists. He was better off financially, yet continued to look elsewhere. A photograph of him with other convivial Oriel Fellows shows him seated alone and apart. EJ regretted never being elected to the Athenaeum in London: ‘English affairs of every kind are run from two or three clubs, and the Athenaeum is where you meet everyone.’ It might, he thought, have purchased him more influence.

The title of one poem, ‘Repentance for Political Activity’, gives a potent clue to his state of mind. Could he have read his own obituaries in 1946, little would have hurt more than the one dismissive sentence, ‘He also wrote poetry.’ EJ passionately wished to be remembered as Thompson-the-poet. In reality he was known sometimes as Thompson-the-writer but more often as Thompson-the-writer-on-India and political activist. Though in 1932 he published an anthology of religious verse, O World Invisible, and in 1935 A Life of Sir Walter Raleigh, followed by a biography of Robert Bridges, India was still his main – partly involuntary – focus. When despondent EJ would quip that the mere mention of the word ‘India’ was enough to empty the smallest hall in Oxford. He was none the less in increasing demand to speak and write about India, often on stage in public debate, importuned alike by literary editors and campaigners of all political hues.

In 1931 he published a sequel to An Indian Day entitled A Farewell to India. Gandhi himself noted the unconscious irony of this second title. Within a day of landing for the Round Table Conference on India in London in September 1931, Gandhi came to Boars Hill with his famous spinning wheel. A photograph of him at Scar Top survives; whether the pet goat with whom he also travelled was in attendance is not recorded. After Theo had served breakfast to his three followers, she discovered Gandhi-ji himself asleep in front of the drawing-room fire, exhausted from a punishing schedule. Gandhi interrogated EJ as follows:

‘They tell me, Mr Thompson, that you have published a book entitled A Farewell to India?’

‘That is so, Mahatmaji.’

‘Well, it seems to me that you have been wasting your time again. How do you think that you are ever going to say farewell to India? You are India’s prisoner.’

Gandhi in the Thompsons’ garden at Boars Hill during the 1931 Round Table Conference.

‘India’s prisoner’ is apt and eloquent. EP later remembered the hushed, reverent atmosphere in the normally boisterous household when Gandhi visited. The young EP did not doubt but that Indians were their most important visitors: the sideboard laden with grapes and dates plus the exotic postage stamps to be cadged off Indian visitors both attested as much. As for EJ, although he liked and admired Gandhi this did not stop him depicting him in A Farewell to India as acting more out of instinct and passion than reason, and later he would sometimes despair of Gandhi’s common sense.

Gandhi was none the less accurate in pointing out that EJ’s valediction to India was premature. Following publication of A Farewell to India EJ revisited India three times aided by grants from the Rhodes Trustees – in 1932 to survey the vernacular literatures of several provinces; in 1937 to access unpublished material relevant to his book The Making of the Indian Princes (1943); finally in late 1939 to report on the political situation on the outbreak of war. His output on India in the 1930s was prodigious, an obsession explored in many different genres.23

In 1935 EJ wrote to Frank: ‘On Tues I saw Jawaharlal Nehru who was President of the National Congress in 1929, when they passed their Independence Resolution. A v. tired embittered man, just out of prison and having left a dying wife in Germany.’ (Nehru’s wife Kamala died weeks later in Lausanne of TB, aged only thirty-seven.) Nehru told EJ he had done an autobiography ‘in which he attacks me’ and sometimes he launched savage tirades. To soothe him EJ took him to meet that ‘old India hand’ Herbert Fisher, Warden of New College, who had served as Royal Commissioner in India in 1912–15, and with whom Nehru chatted happily about histories and other books. EJ naively reported to Frank that ‘It was what [Nehru] wanted, as an old Harrow & Cambridge bloke who went to India to find the British clubs shut against him.’

The implication that Nehru’s deepest resentment in the 1930s was of mere social exclusion says more about EJ than it does about Nehru, whose grandly patrician relatives were fully aware that missionary families like the Thompsons were ‘scarcely top-drawer’. Nehru went to prison nine times for agitating for full independence for India, while EJ held out for Dominion status. So any emollient effect from visiting the pompous, long-winded Fisher – whose first cousin Virginia Woolf recorded him as ‘so distinguished yet . . . so empty’ – can scarcely have been long-lasting.

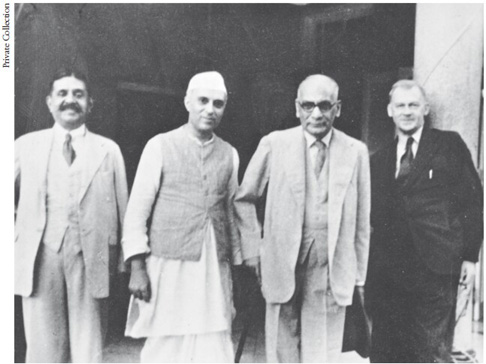

Nehru (second left ) and EJ (right).

Nehru’s affection for EJ and his family was none the less real, and EJ’s lifelong gift for friendship and empathy overrode much. On the Thompsons’ backyard cricket pitch Nehru gave EP batting lessons, doubtless with tips picked up at Harrow and Cambridge. Over the succeeding years Nehru, even when in prison for sedition against the Raj, corresponded with the Thompsons, who long held that when Nehru’s daughter Indira Gandhi married, she did so in a sari belonging to Theo. When EJ published You Have Lived through All This: An Anatomy of the Age, his dedication ran ‘To Jawaharlal Nehru: In Friendship’.

There was always passionate discussion at Scar Top of international and domestic politics, all the Thompsons appearing formidably intelligent and well informed. Seriousness was none the less leavened with humour. The family’s 1933 Christmas charade featured Hitler in the year of his accession to power, and joked that Pushkin the family cat feared the Nazis might take away his mice. And even during solemn intervals when distinguished Indians visited, EJ also played practical jokes on all his guests – balancing untoward items over doors and planting others in beds.

The in-jokes typifying Thompson home-life were never intended for public scrutiny. Family was ‘Fambly’, EJ was ‘Dadza’, and Theo ‘The GM’ or ‘Great Muvverkins’ or ‘Mwonk’, about whose ‘terrifying fierceness’ many jokes circulated. Talking Cockney and American were staple drolleries. The GM hailed from the United States of ‘Amurka’ via missionaries in ‘Soorya’. Theo herself would ape a strong NY accent when quoting one of her rich aunts on the possibility of cutting Theo’s hair: ‘What, cut Theo’s hair? Why she’d be the ugliest girl in Brooklyn.’ Perhaps Theo’s fierceness came out of her own womanly unconfidence and exclusion – from Oxford, from Indian affairs.

All Thompsons wrote ‘pomes’ (many do so today). Frank and EP as teenagers picked up the note of clowning, Frank writing to his younger brother ‘To Ugliface from Handsome’, ‘Dear Ship-mate’ and ‘You horrible Beast’, signing off ‘wiv plenny of lurv’ and, once, ‘Hippopotamus’. EJ’s punning could be heavy-handed: Robert Graves was the ‘Sepulchral Bob’, to distinguish him from Robert Bridges the ‘Pontine Bob’. More embarrassing are his inept attempts to claim friendship by referring to Betjeman as ‘Jack’ Betjeman, Churchill’s son Randolph as ‘Randy’, and the film-maker Michael Powell, with whom EJ hobnobbed during the war (when Powell’s partnership with Emeric Pressburger made both famous), successively as ‘Mick Powell’ and then as ‘Mike Powell’, making painfully clear how threadbare such acquaintanceships really were. Hopkins, to whose poetry his boys were partial, becomes ‘Gerry’ Hopkins. On meeting Lady Ottoline Morrell’s husband Philip to discuss Lord William Bentinck, he ‘wangled’ a tea at Garsington, the Morrells’ Oxfordshire house, for Theo.

Of course what Victorians termed EJ’s tuft-hunting (social climbing) is easy to mock.24 The insecurity behind name-dropping probably fuelled his boys’ compassion; they were a close family and understood EJ’s particular, painful struggle. He was also a good father, was a tireless friend to India, tried to be a kind husband and was generous to other talents. Both Frank and EP were powerfully influenced by their parents’ interests and attitudes. Albeit that in politics they would soon part company, both shared their father’s passionate love of literature. Both loved their father while seeing that the liberal synthesis he represented was in worldwide crisis.

During 1938 EJ spent time cultivating Alexander Korda, who wished to film EJ’s novel Burmese Silver and, before departing for Hollywood that Christmas, offered EJ a one-year retainer. They thought of moving to a large rectory at Lewknor, midway between Denham film studios and Oxford, with a grass tennis court ruined by local lads using it for cricket. There was a five-acre paddock – ‘it’s all very large & will cost a lot to run’. Little came of this.

Frank finally left Winchester during the Easter break to join an Aegean tour, with lectures from Hugh Casson – a Greek odyssey EP would repeat one year later. Though only seventeen Frank seems older: fellow Brits ask him where he is teaching, and Greeks (as we have seen) where his wife is. He writes home, independent-mindedly, ‘Some people are going to dig in Crete in May and I may go with them. Not sure how I will get back to England, but will let you know.’ He fancied he might want to be an archaeologist. Or a diplomat. He left the tour group behind in Athens and was away in the end for three months. His sheer irresponsible, infectious love of life, and ability to turn his adventures to tough-minded comedy, is everywhere in his letters home.

After contriving an empty carriage much of the way to Venice apart from one ‘bloke’ opposite ‘with a face like a rather lewd haddock’, they crossed the Alps where the Italians behaved with their usual inefficient bravado. ‘They collected everybody’s passport three times . . . gave us tremendous documents to sign, and then handed them back stamped, without bothering to look at them.’ He could not take the Fascist Italian seriously as a systematic viper: more as an elemental, misguided clown.

On their first day in Attica Frank and company were much struck by the fierce Greek arguing. ‘It seemed so new & strange’ to them, and they were ‘convulsed with laughter’. Laughter recurs. In Athens he stayed on a camp-bed in the British School library and during the magnificent Easter processions bought a Roman candle which the vendor assured him could safely be held in the hand. On igniting this of course backfired immediately, knocking Frank flat, then ‘slithering venomously along the road and exploding across the street where it nearly killed two women and a policeman . . .’ At Delphi ‘We laughed at everybody and everybody came out and laughed at us.’ At Pergamon in Turkey there was ‘uneasy laughter’ too. His trip continued in this vein; he claimed never to meet a Greek peasant over forty who didn’t make him want to ‘laugh himself sick’.

Frank uses the phrase ‘laughing himself sick’ perversely to betoken laughing with, never laughing at, something that implied a sense of proportion, and sympathy. It was a token of shared humanity, a high compliment. The premium Frank put on laughter is remarkable. When one friend wrote after his death that laughter followed Frank ‘as closely as his shadow’, this was more than conventional condolence. It was not only his own jokes that mattered: he enjoyed others’ too. Laughter combined for Frank the gratifications that the religious get from celebrating the Mass, with a sense of almost physical release, fellowship, close communion. This helps explain some of the intensity of his feelings for Greece, which twice influenced his choice of unit during the war. He longed to return to the land of joyous laughter that reflected – as he saw it – free and courageous spirits; he never felt so happy as among Greeks.

Frank’s humorous ease with others went with groundedness. He discerned that a Greek ex-filmstar they uncovered on board, travelling incognito nominally because she was famous, in reality simply feared revealing her age – in Frank’s words ‘A cattier reason’ for dissembling. Then, accosted by some very intense Brits, and before understanding that they are ‘enemies’ – evangelistic Oxford Groupers on a mission – he ‘hands over most of my key-positions’. When they require his name he blurts out, in a sudden rush of insanity, ‘Michael Foot’25 – another Wykehamist going up to Oxford. Finally in Athens he finds it hard to shake off ‘10 grinning Greeks’ who have already exchanged addresses with him. But this feat he managed.

Love of nature travelled with him too, just as it did his father and brother. Outside Basle he records cowslips and gentians; at the Lion Gate at Mycenae a kind of bee orchid (a species beloved by his father) quite new to him. Near Corfu he ‘arrested a flower under strong suspicion of being a red helleborine and detained it for closer examination’. At Delphi he records the great profusion of fading blue squills, vetches and Compositae, and much more.

That he mostly felt at home in Greece – among its flowers, people and monuments – is clear. He was an adherent of the Philhellenism that has ornamented British life for centuries. One of its premises was that the ancient Greece of Pericles and the modern Greece of the dictator General Metaxas are – if not identical – continuous. Though his passionate wish to serve in Greece was frustrated, this hypothesis fascinated Frank. His final letters in 1944 to and from his brother touch on modern Greek.

The question was primarily linguistic. Frank pointed at objects and tried out the ancient Greek word in modern pronunciation, which worked nine times out of ten – though not for common things such as house, flower, bird. He noted the same nebulosity about special names that the Greeks had in Pericles’ time: every flower and bird named not by its species name but only as ‘flower’ and ‘bird’. Then a Greek employed in the American excavations of the Agora told him they had found a bottle of wine from the first century bc, and – with a wink – that when he drank some it was (improbably) ‘very good’. Athens was a second-rate modern city, Frank thought, but with its Parthenon still belonged to the ancient Greeks.

Parthenon 1938, Frank in foreground (right).

There were other and unexpected reminders of the ancient Greek past. He gives comic descriptions of modern life aboard ship, with two men in his cabin vomiting from sea-sickness from around Samothrace to the Negropont and Artimisium until he recalls that precisely here the whole Persian fleet was wrecked. At Olympia he sees that the ecstasies of Pindar – that beloved ‘mercenary hack-journalist’ – about its beauty are not exaggerated. The high point is Cape Sounion: wonderfully clear blue water, calm and deep immediately you left the rocks – an ideal spot both for bathing and for the ancient temple to Poseidon, dazzlingly white against the fine panorama on all sides: to the north-east the mountains of Euboea and the islands of Andros and Tinos, and to the south-west the Argolid and the Saronic Gulf.

For much of May he worked hard digging on Crete with John Pendlebury, an athlete who had lost one eye but like Frank a Wykehamist, free spirit and would-be writer. Cretans, Frank decided, were a fine set of men, unspoiled by tourists, tough, kind, humorous. On the voyage there Frank had twenty sailors dancing round shouting while he selected some chocolate and ‘had the satisfaction of holding up the whole boat’. Frank was charmed especially by the old men in their grey mustachios, craggy breeches, with huge tail pockets to keep parcels in, thick top-boots, large purple cummerbunds, neat blue embroidered jackets – sometimes even turbaned heads: they had expelled their Turkish overlords only in 1898. He liked the dialect and put up with the squalor of village life: few drains, many cattle, cats, chickens, pigs, goats and donkeys all billeted in the street. Despite Mrs Pendlebury’s best efforts, his lodgings were ineradicably verminous. The bug-bite swellings itched for three days.

The Palace at Knossos, he aptly quipped of his neighbour Sir Arthur Evans’s famously fantastical reconstructions, was less Cretan than Concretan. Evans had recommended Frank to Pendlebury. Pendlebury told Frank funny stories of Sir Arthur and they exchanged light verse and ‘a lot of happy memories’ of Winchester. Pendlebury noted that Frank’s puppyish lunacy combined with ‘a good deal of common sense. His father is the writer on India.’ (To take one example of Marx Brothers humour: Frank had decided that he had about as much chance of a good Balliol scholarship ‘as a whelk winning the Men’s singles at Wimbledon’.) Pendlebury also noted Frank’s rapid clipped speech, a symptom of nervous intensity.

Frank helped Pendlebury at Karphi dig the city where Cretans fled the invading Greeks, with its sumptuous cemetery on the slopes below; here Pendlebury had found Minoan goddesses and Geometric vases. Excavation gave Frank joy – watching a wall work itself out, washing special vases in acid, cleaning and (less thrilling but more restful) sorting and fitting shards into whole pots. Frank boasted that he acquired a varied if shallow view of Greek archaeology. He also boasted that Pendlebury left him for some days in undisputed command overseeing six remaining workmen – one of whom he saved twice from scorpions. Here at the house down in the plain they uncovered a terracotta dolphin-and-rider, red-figure duck vases and over one hundred loom weights. Ancient mod cons at the house impressed Frank: a stone corner seat, stone terraces, tetragons resembling modern Greek slaughtering troughs that might have been for washing.

Though they worked a long day from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. they made time, too, for a pilgrimage to Zeus’ birthplace – the Dictaean Cave at Psychro. The motor car had been unknown in this part of Crete until two years before. Despite the ‘inevitable’ fig tree and wild roses decorating the huge dark cavern, Frank quipped that Zeus on the whole had better taste than he expected. The mountains were still snow-capped when he left in early June.

Pendlebury’s snapshot from behind of a hatted Frank leaving the village on his last day shows a primitive village street. On his last night Frank prepared brandy butter especially so that Pendlebury and he could enjoy an Old Wykehamist dinner with tinned plum pudding. They drank the toast ‘Stet Res Wiccamica’, but Pendlebury couldn’t remember the words to ‘Domum’ nor Frank the tune. Frank liked Pendlebury, finding him forceful, excitable and magnanimous – qualities he shared.

Pendlebury confided that he had had a forlorn face from birth ‘exactly like the archaic smile one finds on early Greek statues’. Connoisseurs of dramatic irony might think such sadness fitting, and Pendlebury predicted to Frank his own role in the coming conflict. He would make a conscious decision to risk his life, training in a British intelligence section which was a precursor of SOE before returning to Crete, where he would famously be shot dead working heroically for the Resistance, aged thirty-six, in May 1941. Frank noted admiringly soon after: ‘It is difficult to think of a higher crown for human achievement.’26 He is buried in the Allied war cemetery at Souda Bay.

After visiting the graves of Keats and Shelley (and much else) in Rome Frank arrived back on 24 June wearing a blue coat and trousers in which he had slept, eaten, drunk and dug for the best part of twelve weeks, much stained and looking the worse for wear. He hoped to get to an Eton and Harrow cricket match the following day, at which event – he reassured his parents – he had always been as faultlessly attired as a member of the Drones Club. That same week, however, he threatened EP that he would visit Kingswood School, where EJ was to preach, sporting an orange tie and purple jacket, so that the whole school got a chance to admire the beauty of his colour scheme: ‘LAUGH THAT OFF!’