Oxford in the Age of Heroes: 1938–9

Even Patroklus died and I must die,

Morning or evening or at blazing noon . . .

from ‘Death of Lykaon’, written August 1938

If you should hear my name among those killed,

Say you have lost a friend, half man, half boy . . .

from ‘To Irushka at the Coming of War’, written 10 July 1939

On his final night in Rome in June 1938, after a farewell dinner in a Jewish restaurant with plenty to drink, Frank next day could not recall how he had got back to his hotel. He overslept and missed the train to London. He was still seventeen, and tales of his getting fighting drunk and passing out would continue until he left Britain for good in March 1941. At Oxford that autumn he failed to turn up to read the lesson in morning chapel.27 On 19 November 1938 he wrote to EP (whose own release from tension came from cigarettes, not from drink)28 with a perfectly intolerable headache after the previous night trying to teach the New College porter to box, before a mixture of whisky and martini made him violently sick.

Instances accumulate. The first time Iris spotted Frank he was very drunk and lying flat on his back in the entrance hall of the Union with his head inside the telephone box. Referring to the bad beer likely to be served Frank in Egypt, Iris in 1941 wrote to his mother, ‘But I suspect that he couldn’t tell one drink from another.’ This appears to have been more than commonplace youthful rebelliousness: his parents feared that Frank might become alcoholic.29

M. R. D. Foot had accepted his grandmother’s bribe of £100 – over half his £180 annual allowance – if he neither smoked nor drank. This may account for the sober clarity with which he recalled Frank’s undergraduate pub crawls, and the frequency with which he was called upon to rescue him. You were allowed to drink in college – four pints in an evening was not unusual – but not in pubs. Frank drank often none the less at the Nag’s Head in Hythe Bridge Street by the canal. One night he had had more than enough and leaving the Lamb and Flag on St Giles at 11 p.m. with Michael, he saw the traffic lights on the Broad were at stop. Frank said, ‘That damned bloody red I’ll smash his face.’ As he climbed the traffic light it changed to green; he collapsed in the quad and had to be carried to bed. It may have been the same evening Frank recalled Michael pouring a stream of cold water over him to sober him up, while next day the university Proctor, after rebuking him for being considerably the worse for wear, tried to swear him to temperance. When he and a friend were thrown out of a cinema because of Frank’s cat-calls it is possible that Frank was in his cups. In June 1939 during his final week in Oxford he was certainly drunk.

He had a nature riche, from which some instinct for self-preservation seems missing. There was the Junior Common Room meeting that Michael asked to have adjourned on the grounds that ‘On a point of order, Mr Chairman, Mr Thompson is on fire.’ He had put his lighted pipe into his left-hand jacket pocket, a trick he pulled off again after visiting his Oxford friend Leo Pliatzky at his family home in Bow. Leo last sighted him on that occasion pausing during his run for the tram, thumping vigorously at his smoking jacket.

Laddish antics apart, why was Frank self-destructive? Partly exhibitionism, while something too was owed to his prophetic certainty about what the political tensions of the times portended for him. His poems continue to record political catastrophe – the extinction first of Austria, then of Spain – and remain grimly visionary. In ‘Death of Lykaon’ he imagines a Homeric hero who, remembering the laughter of boys in meadows where last year he played, is simultaneously Frank himself:

Even Patroklus died and I must die.

Morning or evening or at blazing noon,

With pointed spears or skilful archery,

My fate will come, is coming, all too soon.

What pains or disturbances does this public surrender to ‘fate’ attempt to escape? Theo’s offhand remark about having nearly broken Frank’s spirit is haunting and horrible. ‘Stop apologising,’ his friends would tell him, and when on a Cairo tram some drunken soldiers broke Frank’s finger his comment – ‘Can’t say I blame them’ – seems over-forgiving. (His attempt to discipline them was rewarded by their trying to pitch him through the tram window.) Family tensions played their part in his willingness to embrace suffering. When Frank playfully signs off a humorous letter to Forster ‘Life is hell,’ he is being half-serious too. But if there were rows at home about his drinking, no evidence survives. From March 1939 there were in any case new matters to argue about at home. He had fallen in love with a wholly unsuitable young Irishwoman called Iris Murdoch and, during the same week, she had talked him into joining the Communist Party.

There were many Wykehamists up at Oxford with him. Michael Foot and Frank were both at New College, on different staircases and reading different subjects. In a malicious memoir of his time at Winchester Frank indicates that he and Michael – known because he was pretty as ‘Tootles’ – had not at school been really sympathetic. Frank liked to appear lazy and shabby, his belongings always in a mess; Michael, energetic, tidy, staid and aloof, kept everything sorted and docketed, including one file labelled in large letters ‘Own Works’, and had edifying quotations pinned above his desk. One July Frank turned out to watch a thunderstorm, until a rhythmic tap-tap from an upstairs window made him understand that Michael was by contrast typing a poem in the heat of inspiration. Moreover Michael at school championed the learning of German and it would become fluent enough to assist him when captive in 1944. Frank, while he learned German too, preferred the freedoms of Russian. The implication is both clear and unkind: Frank perceives himself as wild, bohemian and authentic, Michael as conventional and hidebound. Moreover Frank believed that Michael stimulated his emotions deliberately to make melodramatic capital out of them, a charge to which Frank’s poems are not immune.

Michael in his turn thought Frank a romantic ass of the most engaging kind, gauche and tactlessly direct without being shy, but lacking social experience. Something about him connected less with the real world than with a private dream-time; and Frank felt he had a duty to correct the misapprehensions of others. This clash was partly political. Frank, according to Foot, believing in the USSR’s 1936 Constitution, became a libertarian Bolshevik who missed the clause that gave the Party power to override everybody else – even the Constitution – and so set up the Gulag. Tony Forster, by contrast, less troubled by Frank’s further left-wing swing at Oxford, thought Frank got on well with others and wasn’t dreamy.

Frank and Michael in their first term at Oxford marched from the British Museum down to the Spanish Embassy, which was then in the south-east corner of Belgrave Square, each holding one pole of a banner marked ‘Arms for Spain’. They wanted to persuade the Government to sell anti-aircraft guns to the Republic for the defence of Barcelona, saying defensive weapons were not covered by the prevailing British policy of non-intervention. Then both were tellers in statutory white tie and tails at the Union debate on the motion ‘That this House would go to war for Danzig’, which was comfortably carried by four to one – an outcome unreported in the press. Hitler remembered the notorious 1933 Union debate instead: ‘That this House will in no circumstances fight for its King and Country’, passed by 275 votes to 153.

Jimmy Porter in Look Back in Anger in 1956 would famously lament the post-war lack of Good Causes to live or die for. Those at Oxford in 1938–9 suffered no such privation: rarely has any generation been so passionately and intensely engaged. The Spanish Civil War did not end until April 1939 and was, Frank wrote, ‘so real that it hurt’. He attended in one week a farcical meeting in the Town Hall with Stafford Cripps, where £150 was raised to help feed Spanish refugees, and a Spain Social organised by the Peace Council, Frank making, then selling for threepence, lemonade that cost a farthing a glass. They ‘made a lot of money for Spain’.

The mystique and glamour of that final year of peace is not simply a product of retrospective nostalgia. Hope and fear, dread and anxiety all raised the temperature of life, lending to love, friendship and politics alike a rare intensity. Here were students who knew their chances of surviving to twenty-five were slim, who – as Iris would write to Frank – were ‘master of their fate and captain of their soul’, living ‘vividly, individually, wildly, beautifully’. The Munich crisis made war for some weeks seem imminent, until its last-minute postponement. Not for long. The first apocalyptic air war was widely expected, with millions of casualties.

Neville Chamberlain had just betrayed the Czechs, abjectly surrendering to Hitler’s bullying ultimatum at a meeting at which Czechoslovakia was not even represented. Nehru, then in Prague himself, wrote to EJ warning him about the crisis. Within weeks of Frank’s arrival the famous Munich by-election was called in Oxford, seen as a vote of confidence in the Prime Minister and his policy of appeasing Fascism. Quintin Hogg, flamboyant and ill-mannered, stood for the Conservatives against the Popular Front candidate ‘Sandy’ Lindsay, Master of Balliol and the first confessed socialist to head an Oxford college. Passions ran high.

Frank pretended to be a press reporter (he represented a student paper called Living Newspaper), mass-observing North Oxford people’s attitude to the crisis and noting the look of hatred that came into people’s eyes when you announced that you were a journalist. Like Ted Heath, Roy Jenkins, Denis Healey and Iris Murdoch, he canvassed for Lindsay; he got booted out from more than one house exhorting people to vote. He also addressed envelopes, delivered handbills, acted as sandwich-man for two hours advertising a trades union demonstration, and secured Sir Arthur Evans’s signature for a protest letter to the Oxford Mail. Theo, until stopped by a policeman, drove round Oxford in procession with ‘Save Peace, Save Czechoslovakia’ pasted over the family car. ‘A vote for Hogg is a vote for Hitler’ read another placard. EJ was writing letters to everyone ‘ticking them off’, and addressing sometimes empty meetings. Frank wrote to EP a cod letter purporting to be from Lord Beaverbrook, so-called first baron of Fleet Street, to Sir Samuel Hoare, pro-Appeasement Conservative politician, ending up with a cartoon of a cat in a scrum-cap and joking that ‘The Thompson family have made their attitude clear from the start.’ (He had been playing a bit of everything – hockey, soccer and rugby. He had grown to six foot with broad shoulders and thick hammy hands, tall, clumsy, still physically a buffoon. But even though big and gangly and ‘with ten thumbs’, his coordination was evidently improving: he scored two tries for the 2nd XV and even played on occasion for the 1st XV.)

Hogg won by a small majority of 15,797 to Lindsay’s 12,363. The defeated Lindsay supporters with their tattered red and yellow rosettes, Frank recorded, confronted the Conservatives in St Aldate’s in their horsey tweed coats, with their carnations and rolled umbrellas, who, they felt, rushed to sneer and crow at them ‘as if after a day’s beagling, or a night in London’. Frank always identified political reaction with blood sports. That not all his friends were like-minded was forgiven: Gabriel Carritt once rode (badly) with the Old Berkshire Hunt to impress a prospective girlfriend; Rex Campbell Thompson shot grouse near Oban. But those dearest to Frank – as to his father – were at least in principle herbivorous. His parents had that August moved to a smaller house in Bledlow, a Buckinghamshire village chosen in part because of its relative absence of the hunting fraternity.

Saunders Close, Bledlow.

Lindsay’s by-election defeat was a bad omen. ‘What depressed us was that obscurantism had triumphed.’ On the Lindsay side were ‘the creative, the generous, the imaginative. In the other we saw only selfishness, stodginess and insincerity.’ ‘A friend bitterly remarked, “I hope North Oxford gets the first bombs, but it would be rough on the Pekinese.”’ Michael Foot added presciently that there were only two alternatives now – to join the Communist Party or abdicate from politics – and Michael could not swallow Communism.

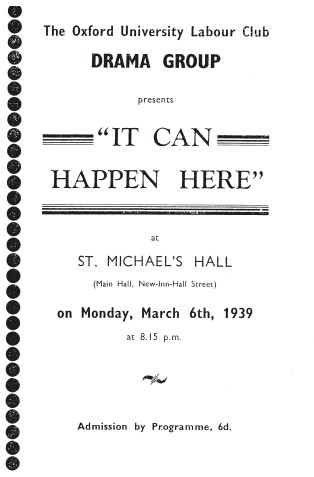

They were still brooding on the by-election defeat in winter 1939 when Frank got involved in co-writing and putting on a play entitled It Can Happen Here, set in an imaginary concentration camp in Christ Church Meadow, where Jews and dissident liberals were interned, with flashbacks, one to the Lindsay Committee Rooms at the by-election. There were six hectic weeks of brainstorming, script conferences and rehearsals. On 28 February Frank wrote: ‘Our play is picking up. It may just shamble into shape in time.’

He collected information on Dachau, which had opened in 1933, and Buchenwald, in 1937. The gassings would not begin for two more years: inmates were starved, tortured and worked to death. The premise of the play was that Fascism had come to Oxford. Learning Anglo-Saxon to emphasise a shared Aryan race-mythology was now compulsory for all: an imaginative touch. The petty law-enforcing Proctors had their own stormtroopers, and the ‘Noes’ door at the Union was blocked up because free speech had been abolished. The play was put on at 8.15 p.m. on 6 March 1939, admission price 6d, in St Michael’s Hall to a (largely) Labour Club audience, and was well received. Although futuristic and intended to be more grim than farcical, the play elicited laughter too. Frank had a dialogue with a girl saying something like ‘You never give me any encouragement: how can a man be expected to do anything?’ Everyone laughed: that sort of line suited Frank. The Labour Club was reputed to have the best women, with whom temporary ‘line-ups’ might sometimes develop into an affair.30 Frank hoped to find a girl, and within days was acting out this role of lover-frustrated-by-his-muse in real life.

Frank had noticed and been impressed by Iris at a Labour Club meeting at Queen’s College in November, listening to Stephen Spender give a woolly speech about Spain and ‘the poet in politics’. Munich, he wrote, ‘still filled us with a deep restless anger’. The hall which Spender described, foolishly, as a ‘glorified railway station’ was packed and steaming. Students were sitting on the tables and the floor. Frank managed to squeeze on to a bench against a wall where, possibly in drink, he fitfully dozed. When he awoke he noticed at the table in front of him a girl leaning on her elbow. She wasn’t pretty and her figure was too thick to be good.

But there was something about her warm green dress, her long yellow locks like a cavalier’s, and her gentle profile, that gave a pleasing impression of harmony. My feeling of loneliness redoubled. Why didn’t I know anyone like that? I saw her again at a Labour Club Social, dancing, – perhaps ‘waddling’ is a better word, with some poisonous-looking bureaucrat. It wasn’t until the middle of next term that I got a chance to speak to her.

There is a welcome absence of rhetorical afflatus in this first impression. Iris’s absence of prettiness, tendency to plumpness and ‘waddling’ dance are all calmly recorded. Yet there is also a ‘pleasing impression of harmony’, one that struck him again when he finally met her the following March, and the affinity he felt between them was put to the test.

Frank (who acted ‘Dennis Fairlie’ in It Can Happen Here) and Leo Pliatzky (poor, cynical, good at insolence, who wrote but did not act) went on a pub crawl that night of 6 March 1939, ending up with a 12s 6d bottle of whisky in the producer Doug Lowe’s rooms in Ruskin College. Leonie Marsh (who also acted) had seen to it that Iris, ‘the dream-girl to whom I’d never spoken’, was with them. Leonie had a double interest in bringing Frank there: she found him attractive, and she had told Iris the previous term, ‘There’s Frank Thompson, a most remarkable man. We must get him into the Party.’

Frank learned just before meeting her that Iris was a classicist, something he had ‘never dared to hope’. Lowe now informed Frank that Iris was ‘a nice girl, and pretty easy too, from wot I ’ear’: Lowe conceiving himself an expert, boasting ‘Oi never tike a girl to the pichers, unless its definitely understood that she wants penis afterwards and Oi said to m’self, there’s a short trip for the SS penis there.’ Frank, too, delighted in bawdiness. But such boasting was wishful thinking on Lowe’s part: Iris’s promiscuous period came later, after she left Oxford. For now, with icy determination, she was set on hanging on to her virginity until after she had gained a First.

Doug Lowe, on one side of the bed in Ruskin College on which Iris reclined, started to ‘paw’ her. Frank, on the other, wanted to stroke her too. ‘Anyone would want to stroke Iris.’ Indeed a ‘witty liberal’ was trying to edge Frank out. But as Frank could see that Iris did not wish to be pawed, and wanting to make a good impression first time despite being pretty drunk, he grew solemn and started on politics.

EJ’s left-leaning liberalism had hitherto influenced Frank. Their painter-neighbour Hilda Harrisson had taken the Thompsons to meet Lord Asquith in retirement at Sutton Courtney, and EJ, though he would vote Labour in 1945, still considered himself a Liberal of sorts. Frank first sighted Iris on the day he became College secretary of the Liberal Club, while he met her in the flesh in the week that he resigned on the grounds that the Liberal Club was ‘too frivolous’, while the Liberals thought Frank too socialist. But he had no use for the Labour leaders either. Iris asked provocatively, ‘What about the Communist Party?’

Iris’s question astonished him. Frank’s comment after attending a CP tea party during his first term31 – ‘I think that English Communists are really rather sweet’ – resembles a Mitford girl’s, while a College row that February between Trotskyites and Communists seemed ‘as barren and fatuous as schisms within the early Christian church’.

I was dumbstruck. I’d never thought of it before. Right then I couldn’t see anything against it, but I felt it would be wise to wait till I’d sobered up before deciding. So I said, ‘Come to tea in a couple of days and convert me.’ Then I staggered home and lay on a sofa . . . announcing to the world that I had met a stunner of a girl and was joining the Communist party for love of her. But next morning it still seemed good. I read [Lenin’s] State and Revolution, talked to several people, and soon made up my mind.

By the time Iris came to tea, in his very untidy room with, typically, Liddell and Scott always open on the table, and a large teddy bear and a top hat on the mantelpiece and ‘Voi che sapete’ all too aptly playing on his gramophone (‘You know what thing is love, ladies – See whether I have it in my heart’), there was no need for a conversion. ‘My meeting her was only the point at which quantitative change gave place to change in quality.’ Frank pondered: ‘maybe I needed to meet her, to realise how gentle and artistic communists can be. Or maybe I needed to be drunk, so I could consider the question with an open mind.’ Leonie welcomed him into the Party with a ‘dramatic gesture, saved by a wicked smile’. Frank wrote to Tony Forster a long jocular letter with some crucial sentences thrown away at the end: ‘Incidentally I’ve met my dream-girl – a poetic Irish Communist who’s doing Honour Mods. I worship her.’ ‘Worship’ was the mot juste, implying the distance that renders a princesse lointaine, however attractive, ultimately safe.

Much linked Frank and Iris, not merely youthful inexperience and the unusual simplicity friends observed in each. Both were apprentice writers who that April of 1939 wrote bad poems on the fall of Spain to Franco. Both took a bohemian and romantic view of the world, and both loved those lines from Julius Caesar – ‘If we do meet again, why, we shall smile; / If not, why then, this parting was well made’ – resonant lines in the run-up to a world war. Both were pantheists with a belief in little local gods and both contested imperialism. Iris had been briefly at school with Nehru’s daughter Indira Gandhi, and in a piece in the university newspaper Cherwell noted English condescension towards both Irish and Indians.32 Frank, whose father frequently compared India’s struggle for independence with Ireland’s, and who spent August 1938 in Ireland with his family, will have sympathised.

Iris identified fiercely with Irish nationalism and claimed Anglo-Irish ancestry through her Richardson mother’s family, with its erstwhile big houses in County Tyrone. Her family had come down in the world. Her maternal aunt Gertie Bell was an alcoholic married to a Dublin car mechanic, three of whose sons worked as fitter, storeman and long-distance lorry driver for Cadbury’s, and Iris was the first of her family to acquire higher education. She believed – unreliably – that she had lived in Ireland for her first two years and the brogue she affected was borrowed from her parents. She was given to unlikely imprecations for an Irish Protestant such as ‘Holy Mother of God’. Iris Murdoch was a tough-minded woman whose enemies claimed she was coated with ice.

The group associated with It Can Happen Here took to ‘knocking about together’: Frank, Leonie Marsh, Leo, Iris and also Michael Foot. ‘That was a bad passage, the first fortnight of the 1939 summer term,’ wrote Frank:

Like something in rather poor taste by de Musset. I was pining green for Iris, who was gently sympathetic but not at all helpful. Michael was lashing himself into a frenzy for Leonie [Marsh] who would draw him on and then let him down with a thud. In the evenings we would swap sorrows and read bits of Verlaine to each other.

There is something willed about all such infatuation, as well as something involuntary. When Frank wrote in one poem to Iris (‘Himeros’) of wishing to lay his head in her lap and weep away his troubles, or in another to her (‘Defeat’) ‘To feel your hair caress my cheeks, and rest / Til death on the soft fullness of your breast’, he is invoking a Keatsian beloved whose alarming remoteness recalls his mother’s. Both Iris and Theo could express warmth in letters; neither did so easily in person. A retrospective 1943 poem Iris drafted but never sent to Frank contains the lines ‘folded in your room, your story and your arms’ while her quietly beating heart judged ‘the long distance’ between them. Probably a chaste embrace was all he achieved. Intensity like Frank’s can repel.

Frank spent three whole days that May walking round and round New College gardens, observing the chestnuts bearing their white candles, the pink tulips and blue forget-me-nots, in intervals between writing Iris letters and tearing them up. He wrote her bad poems expressing ‘calf-love’.33 Iris ‘with her gentleness and her simplicity’ was the person from whom he wanted to hear good news about himself. ‘But Iris never told a lie yet, so I got worse and worse.’ His friends watched in baffled unease. He stopped sleeping, started talking to himself, gardening, going for walks, climbing trees. Michael hid Frank’s cut-throat razor from him. Leo, less melodramatic, more down-to-earth and sexually confident, invited him to dinner. When, one evening, Iris disappeared into Doug Lowe’s rooms in Ruskin, Frank was in such a bad way that he escaped to spend a week at home. On the practical advice of Theo, who had ambitions for her sons’ marriages, he dug up an entire bed of irises as a counter-charm. Other things cheered him. There was the ‘big joyous world of his friends, not only political ones’. He found comfort in the idylls of Theocritus, especially the tenth, ‘The Reapers’, which features a lovesick youth, and in the love-poets Bion and Moschus, whom he quoted to Iris ‘exuberantly’.

Michael Foot was crazy about Leonie, who adored Frank, who was hopelessly in love with Iris. If Iris had then loved Michael, which happened later, that would then have made a perfect quartet of frustrated desire, like that in Act III of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and doubtless one blueprint – there would be others – for the love-vortices of her novels. Of this unhappy love quartet, Frank joked in a parody of Marxist-Leninist Newspeak: ‘It’s not shortage of resources that’s the problem, comrades. It’s maldistribution of supplies.’

Scarcity of resources, however, played its part. The ratio of men to women at Oxford at that time exceeded six to one, so that girl undergraduates regularly received attentions disproportionate to their charms. Among those paying court to buxom, fresh-faced, dirndl-clad and still very blonde Iris Murdoch were Leo Pliatzky, his gentle, dopey friend Noel Martin, kind, warm-hearted, undiplomatic Hal Lidderdale and – once he had recovered from Leonie – Michael Foot. Iris played the role of Zuleika Dobson in Max Beerbohm’s famous 1911 novel of that name: men fell in love with her seemingly on sight, while she stayed impervious.

Frank was a front-runner. A schoolfriend of Frank’s, never in love with her, believed that it was her spiritual quality that gave Iris her appeal; she had, all her life, an extraordinary quality of stillness and attentiveness.

Frank had suffered two coups de foudre together. He fell in love during the same week with Iris and with Communism: two flights of irrationality, it might be said, and two simultaneous conversion experiences. Sexual frustration played its part in the first, political frustration in the second. The Conservative Party, containing some who were actively pro-German, was irretrievably sullied by appeasement, the Labour Party by pacifism until 1935 and by resistance to conscription thereafter. Any undergraduate determined to stop Hitler was easy game for the Communist Party.

The extent of Communist penetration at Oxford is remarkable. The Labour Party in 1935 had permitted fusion of the Communist and Socialist societies at the universities and there were close links between the OULC and the CP headquarters on Hythe Bridge Street. The Labour Club, dominated by Communists, had over 1,000 members; nearly all its committee members were in the CP. But then all of the committees of the League of Nations Union, of the Liberal Club and of the Student Christian Movement, two of the five Conservative Club committee members and even two of the ten members of the British Union of Fascists committee were also in the CP. It helps give the atmosphere of the times to point out that Robert Conquest, while an open Communist, was a member of the university’s Carlton Club, with the full approval of both bodies, and that the CP included John Biggs-Davison, later Chairman of the right-wing Monday Club.

Idealism, romanticism and a passionate anti-Fascism came together to move the best of a generation left-wards, into the Popular Front of all progressive forces opposed to appeasing Fascism, that famous ‘Stage army of the Good’. The Oxford by-election was just such an anti-appeasement, Popular Front campaign, the Labour and Liberal parties agreeing not to field rival candidates against their Tory opponent. Some CP members still wanted a genuine alliance of left/radical opinion within the Popular Front that included the CP, rather than a secret recruiting ground for committed membership into the CP.

Frank himself often noticed that the Party appealed to opposed psychological types: the ‘uncontrolled romantic and the cold blooded theorist’. He classified Leonie Marsh – over-sexed and over-emotional – together with himself in the first category. On the way back in January 1939 from Val d’Isère, where he had skied, made friends, practised his good, idiomatic French and read four books of The Iliad, he wondered what territories had lost their freedom to the Fascists while he was abroad. He then recorded a need to weep ‘to think of the many good friends whom I have known for a few days and then left’. He was an eighteen-year-old sentimentalist, inexperienced and immature. The approach of war heightened emotions too.

His pull towards Communism lay in its promise of universal brotherhood, an imaginary politics of kindness, caring and compassion, and the belief in a utopian future to stand against the evident bankruptcies of capitalism and the nightmare world of Fascism. EP would later invent a brilliant phrase – ‘the chiliasm of despair’34 – to help explain Methodism’s appeal around 1790. The phrase implies that a final conflict between good and evil is about to occur, an end of the world as prophesied in the Book of Revelation. It has its aptness to 1930s Communists. Book after book – Spender’s Forward from Liberalism (1937) and John Strachey’s Why You Should be a Socialist (1938) – announced that liberal democracy and capitalism were in their death throes, and mass unemployment, hunger marches and the rise of Nazism all symptomatic of final collapse. The belief that a better system must exist and could be born out of the coming apocalyptic struggle, while irrational, is not hard to understand.

To be a CP member was moreover to belong to a European-style intelligentsia, opposed to the narrow racist and nationalist ideologies of the far right. This appealed. Lastly, when Iris showed Frank ‘how gentle and artistic communists can be’ he was discovering another forgotten aspect of 1930s Communism: that it sanctioned creativity. Many painters and writers were CP members or sympathisers.35

Frank was soon preaching the new gospel. There were fierce arguments, especially with his father at home, where Frank attempted to sell the Daily Worker in nearby Princes Risborough. He started to study and discuss dialectical materialism with those to whom he felt the future belonged, and to understand European history better; he benefited from its intellectual toughness. Yet although he recorded later that he spent that ‘undistinguished year studying Greek and Socialism’, Frank never became a dogmatic theorist. He left behind him no body of Marxist theorising to compare, for example, with the writings of John Cornford, that martyr of mythic power who had died in Spain aged only twenty-one and who at Cambridge spent fourteen hours each day on politics. Frank’s scattergun interests are the exact opposite of Cornford’s ‘fierce single-mindedness of thought and action’.

Listening to the General Secretary Harry Pollitt give a rousing speech at a CPGB (Communist Party of Great Britain) youth camp that summer, Frank wrote to EP (addressed jokingly as Lev Davidovich – that is, Trotsky) remarking how nice it was to hear a spot of idealism ‘because Communism tends to be a cold rational creed’. Frank always placed a high premium on human ‘warmth’, and, if his generation was of course ludicrously, grievously deluded about Stalin’s Russia, it was a generous error.36

In 1936–7 alone two million had died in Stalin’s purges, facts not hidden at the time: Malcolm Muggeridge and George Orwell observed accurately and testified. The appeal of Communism has been often discussed by those wishing to expose Communists as dupes and fools (from Orwell to Martin Amis’s Koba the Dread) or traitors (Alan Bennett’s A Question of Attribution). And yet we inevitably read this heroic generation through the distorting lens of the Cold War; and ‘heroic’ seems the right word.

With a duty of judging comes the challenge of understanding. Iris, who joined the Party as soon as she came up to Oxford, had been prepared by the ethos of her dotty Badminton School headmistress, who gave sermons on the sanctity of Lenin, Gandhi and Sir Stafford Cripps, and whose mistresses familiarly addressed one another as ‘Com’ for Comrade. Beatrice Webb rightly described 1930s Communists as ‘those mild-mannered desperadoes’.

An attractive feature of Frank’s generation of idealists is their willingness to get their hands dirty, to step out and help. His parents trained him to be civic-minded and public-spirited. Between April and July 1939 he helped with New College Crown Boys Club in the slums of Hoxton in north-east London, of which he was Secretary and for whose boys he acted in a pantomime as cannibal King Umballuna in his father’s battered top hat. The poverty of the East End shocked him. He then taught at a school for Jewish refugees in Kent, followed by a fortnight in a camp for the unemployed in Wales, returning home flea-ridden, and finally attended CP summer school. This in addition to reading ten books of Virgil, six of Homer, and Hesiod’s Works and Days and all his duties as an Oxford undergraduate. Small surprise that Frank found classics, which he had gone up to study, irrelevant to the political crises obsessing them all. He regretted not studying Russian instead.

During Easter 1939 Frank went in response to an urgent appeal for help to New Herrlingen School at Otterden in Kent. No official notice was at first taken of him until the headmistress, whom he called ‘Tante Anna’ (‘cylindrical and with a squint’), looked sternly at him saying, ‘Are you interested in this sort of work or have you come merely because you want somewhere to stay in the hols?’ Frank gave a strangled gurgle. His programme, she explained, was to talk English with the German pupils, and play games with them in the afternoon on his own initiative. He was to look out for three adults, fresh from concentration camp, who might teach him German.

Headmistress Anna Essinger, that remarkable woman, founded her progressive boarding school near Ulm in 1926. When in 1933 Hitler came to power she soon realised that there was no future in Germany for her and the children, many of whom, like her, were Jewish. Accompanied by some seventy pupils she refounded the school in Kent. A committee of Quakers and others helped Essinger rent and then buy Bunce Court, a large country house with extensive grounds. So many refugee children arrived in the UK in 1939 that she organised an emergency programme to help them through the Jewish Refugee Committee and the Quakers, even when no fees could be paid. Her school provided a home particularly for those children whose parents perished in the camps. They received not only a good and stimulating education but in the absence of domestic staff took on the tasks of cleaning, cooking, growing vegetables, repairing furniture, converting stables into dormitories and more. Pupils included the painter Frank Auerbach and the artist, musician and humorist Gerard Hoffnung.

Frank looked without success for the three fresh from a concentration camp to teach him German. He took classes and play-reading and discovered that he liked teaching, finding these children much more intelligent than average. He got permission to attend a Seder evening on the Friday night of Passover with its Haggadah service, and, since Jewish men wore hats both before and during the supper, he from respect donned his green beret. He worked out that the order of service probably dated from the fourteenth century and wondered whether its references to ‘Next Year in Jerusalem’ were in that century already Zionist – a sensitive question for pro-Arab Jessups like Theo. He heard first-hand accounts of German troops a few weeks earlier on 15 March marching into Prague, which the Luftwaffe, its aeroplanes visible overhead, threatened to bomb. When a Jewish child of nine with large eyes looked up at Frank and pleaded with him to obtain a permit to get his parents out of Germany, he was profoundly unsettled.

The do-gooding of 1930s left-wing intelligentsia is a source of satirical fun in stories by Angus Wilson such as ‘Such Darling Dodos’, yet their altruism is surely preferable to cynicism or despair. Iris would later, accurately, call the 1930s a time when many felt themselves to be trapped witnesses of history or ‘conscience-ridden spectators’. That is well said and, although Iris also attended CP summer school in Surrey, no evidence of her doing welfare work survives. She spent the last weeks of peace in the Cotswolds with a group of touring actors called the Magpie Players. But Frank did more than spectate; the sense of belonging to a bigger cause lent his life new sweetness and meaning.

Iris Murdoch and Joanne Yexley on the Magpies’ Tour, Bucklebury, 22 August 1939.

He hated government inertia in the face of social hardship. Depicting himself as lazy, he in fact liked work: and if he was, in the jargon, ‘slumming’, he intended to do so thoroughly. At the Unemployed Camp in Carmarthenshire that July he disliked not being made to work hard enough and wished he could sign up for a week and work arduously and straight through, rather than in shifts. When it rained they had to waste time indoors playing whist while listening to the bad sentimental songs the unemployed liked to sing at the top of their voices about mill-streams and ‘the one I love’: his nerves suffered. But, often hungry himself, he recorded an attractive piece of dialogue, with two men saying, ‘Hungry, whateffer? . . . I could eat a dead horse between two bloody bread-vans.’

He also recorded that he got drunk. His breakages included two tables and, he claimed, one chandelier.

The cleverest man they knew, Frank’s friends thought, had fallen hook, line and sinker for tommy-rot and believed Stalin wonderful. The appeal of the CP was quasi-religious: Raymond Carr’s ceremony of induction at Queen’s College resembled a religious service, ‘with candles and oaths’. Cecil Day Lewis reported that his generation had lost their Christian faith, despaired of liberalism as an outworn creed, and greeted Communism for its romantic, crypto-religious appeal, its radiant illusion that the world could be put to rights. Frank agreed with his father, who wrote to Nehru that year that religion was ‘the greatest pest in the world’. The idea that he had joined a new religion would have dismayed Frank, and he would have protested.

Communism was certainly authoritarian and possibly dictatorial, demanding that its members ‘sink their egos’ for the higher good; and both the police and the Special Branch accordingly took a great interest in its activities. CP recruits were expected to toe the Party line, attend Party meetings, organise, speak, sell Party literature, join outside bodies and ‘front’ them. Philip Toynbee recorded that ‘the Oxford CP practised dishonesty almost as a principle. It was indelicate, authoritarian and possessive . . . [displaying] a crudity of judgement which . . . extended to a bluff insensitivity about love affairs . . . There was a “line” for love; there was almost a line for friendship.’ In this light Leonie Marsh’s injunction to Iris that Frank was a remarkable man whom they ‘must get in’ to the Party sounds cold and sinister.

Frank and Iris processed together in that year’s May Day parade over Magdalen Bridge and up the High Street, Frank, not yet nineteen, in emotional turmoil. This came at the beginning of his final term. In late June Frank’s Oxford career ended rather as it had begun, in a drunken night with friends:

In Corpus [Christi College] everyone stands one drinks and I was pretty whistled . . . After I had eaten two tulips in the quad and bust a window, they dragged me into Leo’s room and sat on me. I calmed down and they thought I was safe enough to take on the river. The red clouds round Magdalen tower were fading to grey, when we met two people we didn’t like. We chased them and tried to upset their canoe. We got slowed up at the [punt] rollers, and then I dropped my paddle. With the excitement all the beer surged up in me. Shouting the historic slogan, ‘All hands to the defence of the Soviet fatherland!’ I plunged into the river. They fished me out but I plunged in again. By a series of forced marches they dragged me back and dumped me on the disgusted porter at the Holywell gate. After bursting into ‘an important meeting of the college communist group’ Comrade Foot, by a unanimous vote, was given ‘the revolutionary task of putting Frank to bed’.

That was probably the only CP meeting Michael attended; and sixty years later Sir Leo Pliatzky, by then a retired permanent secretary, remembered both his alarm when Frank that night disappeared below the water and his relief at the rescue. Frank’s account turns recklessness, once more, into high farce. His chief audience and muse alike was Iris. (Later they switched roles.)

As well as, doubtless, letters now lost, Frank wrote many poems dedicated to her. You can sense in his ‘To Irushka at the Coming of War’ written in July 1939 that he is using the sonnet form half-deliberately to stoke up his emotions, like Romeo with Rosaline, getting the maximum possible dramatic return out of his situation:

If you should hear my name among those killed,

Say you have lost a friend, half man, half boy,

Who, if the years had spared him might have built

Within him courage strength and harmony

Uncouth and garrulous his tangled mind

Seething with warm ideas of truth and light,

His help was worthless. Yet had fate been kind

He might have learned to steel himself and fight.

He thought he loved you. By what right could he

Claim such high praise, who only felt his frame

Riddled with burning lead, and failed to see

His own false pride behind the barrel’s flame?

Say you have lost a friend and then forget.

Stronger and truer ones are with you yet.

(‘I liked the poem because it was like you: simplicity tinged with melodrama. You’re a darling,’ Iris astutely commented; to these qualities we return later.) His sprezzatura here concerns the conceit that Frank is inviting Iris to forget him while he yet lives – a rhetorical strategy recalling Shakespeare in Sonnet 73, inviting his beloved to take pity on him because of his expected early demise: ‘This thou perceivest, which makes thy love more strong, / To love that well which thou must leave ere long.’

Frank’s sonnet is entitled ‘On the Coming of War’. On the momentous morning of Sunday 3 September when war was finally declared Tony Forster, visiting Bledlow, said, ‘Whatever happens, we’re going to have an interesting time.’ Frank drily reminded him of the Chinese curse, ‘May you live in interesting times.’ By that Saturday, one crucial day before, Frank had joined up. Just turned nineteen and thus under-age, he quarrelled furiously with his parents. Theo rang ‘a large number of Generals’ and also the College authorities and, on the grounds of youth and uncompleted studies, got the War Office to rescind his enlistment. Stormy scenes lasted for days before Frank prevailed. Not all parents could have managed that, nor all sons.

Other Winchester contemporaries signed up – John Hasted unsuccessfully; but the Winchester scholar David Scott-Malden joined the RAF. The second of two short stanzas Frank dedicated to David runs:

You went, my friend,

To spread your wings on the morning;

I to the gun’s cold elegance; and one

– Did you feel the passing of a shadow

Between the glasses? – one will not return.

What made Frank predict that one of them would not come back, when the likelihood must have been that neither would return? Scott-Malden, Battle of Britain fighter pilot commanding a fighter sector station by the age of twenty-three, DSO, DFC and Bar and Norwegian War Cross, was to die an air vice marshal on 1 March 2000, at the age of eighty. Frank would be killed at twenty-three in Bulgaria. His prescience, not for the first or last time, is unsettling.

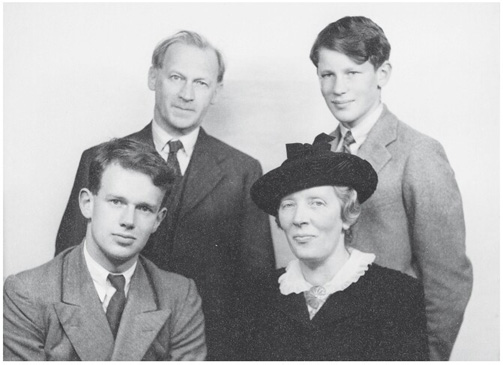

Family portrait, 1939.