Cairo Frustrations: March–December 1941

I shall be burned out at 23. I must seek an early death to keep my flame untarnished and immortal.

Frank writing to Désirée in April 1941

The HMT Pasteur left Gourock on the Firth of Clyde on 19 March 1941. On board this former luxury liner built to carry a few hundred passengers and crew on the South America run were around 3,600 men; some had travelled eighteen hours prior to embarkation and all wartime trains were unheated. Phantom H Squadron contributed to this huge draft its fifty-one men and five officers, with Captain Peter Forshall, a former stockbroker, taking command and Frank, a former undergraduate, his acting second-in-command. Three other officers had joined Phantom only two days before sailing. Phantom H was headed for Greece via Cairo but, to minimise risk, the ship took the long route, towards Canada, doubling back via Sierra Leone before rounding the Cape and sailing for seven weeks in all.

After pelting rain and an air raid had detained them in Glasgow, they had boarded the Pasteur from ferries up a wet rope ladder – an interesting climb when trying to balance rifle, haversack, steel helmet, gas mask and bulging kitbag.

As the ship pulled out Frank noticed snow veining the hilltops, and watched a train slowly pass, before the Clydeside women and children waved and cheered – from filthy tenement balconies where linen was drying, from windows and from warehouse doors – for all that they were worth. Since meetings and processions were forbidden, opportunities for fraternisation were rare, and as scarcely one in a hundred was waving a Union Jack, Frank took their cheering for a show not of jingoism but of solidarity with all who suffered the indignity and servitude imposed by war. The troops on board in their turn hit back with a roar that shook the houses. This exchange of sympathy gladdened his heart.

Frank’s diary makes a fierce indictment of this ship, embodying all that was wrong with Britain. Officers enjoyed luxurious six-course dinners, with printed menus on every table even at breakfast, and unrationed butter and sugar, while the long queue for other ranks to reach the canteen took three hours: ‘Shop early for Christmas’ they joked good-naturedly. Conditions below deck were dismal. The smell of 300 tons of rotting cabbage from the swimming pool pervaded everywhere; there were only four cells to accommodate the 120 men handcuffed because they had gone absent without leave (none from Phantom). The washrooms provided no baths, few showers, latrines that stank even before the sea-sickness of the voyage began and twenty basins only, some shared by up to 400 men. Water, moreover, was turned on for only four hours each day, and there were no laundry facilities. Floors and even meal tables were solid with sleeping men, while hammocks slung from the roof reminded Frank of bats roosting in an attic. Troops stared dumbstruck through the door of the opulent officers’ mess at the spectacle ‘as wondrous as the drinking scene from Gounod’s Faust’, where two boys from the Black Watch danced arm in arm, the room black with noise, excess of drink and tobacco. Frank wondered if it would ease the appalling congestion below deck if the troops took over the sergeants’ and officers’ lounges.

The men’s satirical good humour was meant to be overheard by the officers – ‘I say old chap I think I’ll take my tea in bed this morning’ – and impressed Frank. His fellow officers did not impress. One officer, unable to stand up straight himself, arrested five men for drunkenness. Some never went below deck at all, making no attempt to organise programmes for their men during their two months at sea, preferring with the padres to chat up nurses in the lounge, or dance with them on a deck where men were trying to sleep.

Frank, whose identity disc now proclaimed him ‘Atheist’, saw no priest of any denomination venture below deck nor even talk to the men above deck. Only the Catholic and non-conformist padres appeared to care – and even then only in theory – about their jobs. The Anglican padres he found mostly selfish, dirty, time-serving, petty-minded and ‘cabotin’ – French for ham-actor. One wished chiefly to discuss sodomy; another on church parade, imagining that the troops shared the same living conditions as he did, fatuously thanked God for ‘this luxury cruise’.

Forshall was confined to his cabin with sea-sickness, then sunstroke, then earache. The twenty-year-old Frank deputised, acting commander to fifty men, facing Britain’s systemic rottenness and inequity. How should he help? He frequented the lower decks and fraternised with the men. Since the Pasteur lacked ‘rolling chocks’ (bilge keels) and, when sideways to a large wave, tilted alarmingly, drill – with the floor alternating between planes forty-five degrees each side of horizontal – was impossible. But Frank and an old Oxford acquaintance offered their men a grounding in modern Greek.50 The diary he kept on board was published in 1947 and has been referred to by historians since. None of his diarising was enough to assuage his sometimes murderous fury and indignation, but it was better than nothing.

A nurse he met on board charmed him; he asked her what it was like to have a man with TB for whom she had fallen die on her hands. Captivating, too, was an olive-green-eyed girl from Yorkshire who pronounced his name ‘Frunck’. But, though there were couples necking shamelessly and, as they headed into warmer weather, copulating on deck, he considered a troopship no place for romance. His recurrent complaint over the next three nomadic years was that intimacy could only be snatched at: you were never in one place long enough to let it grow.

Yet in some ways the nomadism of war suited him. He eagerly anticipated travel and new sights. He wrote a story about the mythical Hyperboreans who worshipped Apollo because they enjoyed his seasonal migrations to visit them in winter. Frank hymned Apollo as god not only of apples but of the singular virtues of restless travel.

Frank had space in his officer’s quarters to read, think, keep a journal, write poetry. Letter-writing, he acknowledged, was his ‘katharsis’, buying him purifying release from inner turbulence. He claimed that his letters to Katya (Catherine Nicholson) and Irushka (Iris) were wasted on them: he flattered his mother that she remained his best audience.

He argued furiously with a right-wing pro-Franco opponent while appreciating this man’s passion: he liked ‘anyone who cares’. His reading on board stayed eclectic. He was trying to patch up his ‘tattered and threadbare’ – that is, truncated – education. Marriott on the Balkans (started at Cliveden) taught him something new about Bulgarians – that they were late-coming non-Slavs who adopted the indigenous language after arrival.

To Désirée he wrote a classic piece of Frankish sprezzatura. He had been reading Shakespeare and identified with Hamlet, that other young man rebelling against a rotten ruling-class background, and claimed that Hamlet’s ‘I am but mad north northwest’ in Act II provided him with a ‘new epitaph’. Frank also identified with Hamlet’s death-wish and continued, ‘I am if anything too brilliant. I am afraid that this my precocity will prove a flash in the pan. I shall be burned out at 23. I must seek an early death to keep my flame untarnished and immortal.’ This mixture of boastfulness (‘too brilliant’), self-deprecation (‘flash in the pan’) and melodrama (‘early death’) is further romantic self-dramatisation.

When they crossed the equator, he had to change his shirt twice daily. He maintained that to enjoy life fully one must always be learning a new language. He compared it to fiddling with the innards of a dormant car engine, or to Pygmalion breathing life into a statue. ‘If the gods were clement’ to him – a recurrent prayer – he would do a lot of translation. Regretting that he had never asked Theo to tutor him, he started on Arabic. Landfall in Cape Town, where they docked at 11 a.m. on 16 April for four days, offered many delights: his first glass of milk for one month, his first ever persimmon; sightseeing by droshky with two Cameron Highlanders; shopping; dancing and – despite pro-Nazi Afrikaners in the Broederbond – much hospitality. He thought he cut a fine figure in shirtsleeves.

During the first week of May they entered Suez, where Frank records without explanation that a provost sergeant major died, and after due rites was tipped overboard. By the time H Squadron had disembarked and made their way to Mena Camp in Egypt near the foot of the Great Pyramid of Cheops, Greece itself had fallen. They were no one’s child: a bad thing to be in any army.

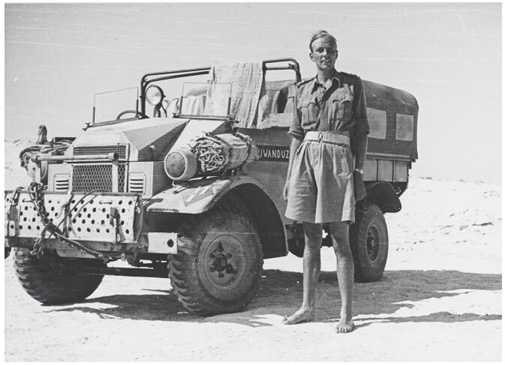

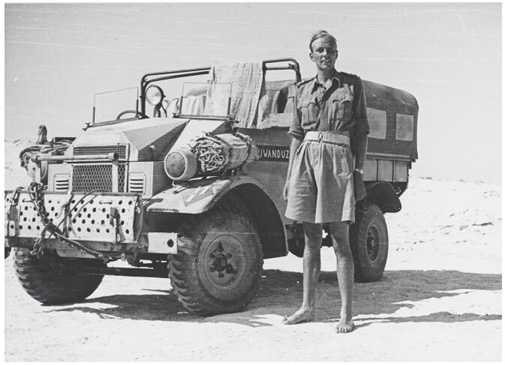

Graham Bell sailed with Frank in March 1941, and stayed with Phantom throughout the war; note the sand mat to extract the vehicle when bogged down.

Creating a private regiment like Phantom, based on the need for fast and accurate front-line communication, was one thing. Convincing others to integrate it into their plans was another. Hoppy had not adequately consulted the War Office about his plans; when the first Phantom group (which Frank’s was intended to reinforce) had sailed to Greece in November they met with a blank or actively hostile reception in Cairo before making their way to Greece. There Miles Reid, commanding the group and wearing a tam-o’-shanter, travelled with his party improbably disguised as American journalists. As in Belgium, Phantom’s fate turned out to be to communicate accurately from a battle zone during a massive rout. Eleven thousand British troops together with much valuable equipment were captured by the Germans, but the Phantom formation proved its worth by bravely and accurately communicating from the front line before most were killed or captured. The twelve survivors slowly made their way to Mena in Egypt to join up with Frank and his second group, together with ten tons of stores, wireless sets, now redundant parcels for the detachment in Greece, and some new shirts for King George of the Hellenes.

H were now the only Phantom squadron on active duty anywhere. They took the news from Greece badly. Their camp occupied a shallow wadi behind the Mena House Hotel with its welcoming swimming pool. One unnamed man who joined them found ‘a rather gloomy little party with little idea of their purpose in life and quite unable to explain it to him’. Phantom was an ‘unbadged’ regiment, a small symptom of their not being wholly accepted by the military establishment and thus suffering a deficit of status and recognition. They wore their previous regimental insignia, their cap badges having a misleading diversity, a few choosing badges they simply fancied, without any entitlement.

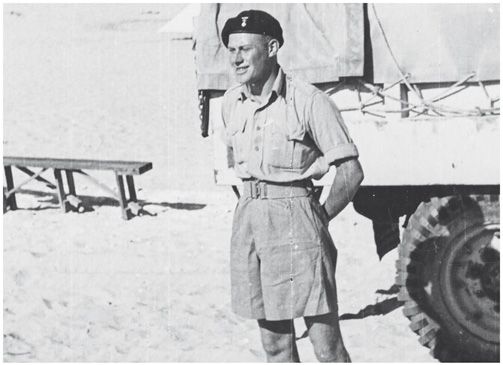

Rex Campbell Thompson c. 1941.

Early June was disturbed by a ‘vile piece of news . . . the worst I ever had’. His childhood and Dragon School friend Rex Campbell Thompson, acting flight commander on a bombing raid over Brest that he radioed home as ‘successful’, was killed when his returning plane crashed on Dartmoor in fog. He was twenty-one. Childhood memories connected them more than Frank’s recently acquired politics divided them: Rex in his pushchair blowing bubbles, diving in the Evans lake, playing scrum-half at the Dragon, witness to Frank’s first pipe and first girlfriend, driving his battered Austin round Boars Hill. Separated by schooling – Rex went to Cheltenham – their friendship rekindled in the single year they were together at New College after which both joined up the same month. The lightness of touch of Frank’s accomplished elegy – one long quietly half-rhymed single sentence of remembrance, with its shock final word ‘buried’ – is moving:

Rex

A word from England brought you back to mind,

Oldest of friends, and how we walked together

From Foxcombe round by Cumnor in the kind

Celandine season or in harebell weather

When haws glow crisp from hedges – dogs that were lost

In long grass hunting rabbits, solemn talk

Of school and coming college, till the last

Visit to Sunningwell, when we tarried,

Liking the churchyard and its yew-dark grass,

Where, if they tell the truth, you now lie buried.

Rex was one of ‘my only two friends of life-long intimacy’. The other was Brian Carritt, who was to die in 1942. Rex came from the same bourgeois world as Frank and shared its inhibitions. In 1938 Frank had prophetically recorded that over-protective parents had not helped Rex decide for himself ‘what risks he is prepared to take about his own life’,51 while a eulogy written about Rex for the Dragon School recorded his ‘desperate shyness’.

During this confused time, when not training, reading or learning languages, Frank sought out fugitives from Greece to piece together a picture of the ‘elephantine stupidity’ of this all too British retreat, during which transport was being unloaded on one part of Piraeus dock, taken for a short drive up the quay, then set on fire. In late June, too, the future writer Paddy Leigh Fermor, ‘a classy captain who eyed the other ranks with disdain’, and who had known Miles Reid in Greece, praised to Frank the quality of Phantom officers there. Others acclaimed Miles’s work blowing bridges in Monastir, reconnoitring the Vardar Valley and ‘triumphantly’ touring the Peloponnese. ‘A fabulous party’, Frank commented excitedly, with an ominous hint of admiration for such heroic escapades and Boy’s Own adventure tales. Frank also heard praise for the humour, hospitality and honesty of the Greeks, who put their own lives at risk to guide the retreating British soldiers to safety, with no bitterness about their own defeat or coming occupation.

Cairo was nightmarish in the heat of summer, and Egyptians hostile to the army of occupation. Expatriate Greeks Frank ran into in clip joints and watering holes made the city endurable, partly because he knew their language. On a memorable July outing with his unit to see St Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai, a Fr Alexandros waived all fees for entry, food and lodging because they were British: ‘unconsciously all Greek exiles identify George VI with George II [of the Hellenes] and speak as if Greece were part of the Commonwealth’. Sinai also helped inspire a good poem, ‘Soliloquy in a Greek Cloister’. He treated Alexandria – where Greek had after all been the main language for nearly 2,000 years – as a Greek city, eating only in Greek restaurants, going to the Greek theatre and talking Greek even to the Egyptian tram-conductors.

Greeks and English were allied politically. But Greeks also knew that life is funny, and that you and they are – there was nothing quite like a Grecian grin ‘with its frank admission that everyone, oneself included, is a bloody fool: but what does it matter?’ Where Brits embarrass one another and blush, Greeks simply shrug off awkward questions and laugh them off together. Apropos the learning of modern Greek Frank commented tellingly that ‘one always feels embarrassed by emotion in one’s own language’. As an ‘emotional Englishman’ he preferred his feelings safely distanced from him, lost in translation. ‘I can only flirt in a foreign language,’ he would add later.

Frank’s strange list of Noble Savages – those idealised races born to transcend British middle-class inhibition – keeps growing. To Americans, Jews, Greeks, Slavs he now adds cockneys with their jaunty humour and – interestingly – sergeants. Frank envied what he termed the ‘Homeric laughter’ of the sergeants’ mess compared to the chilliness of the officers’ mess: as soon as sergeants gathered each evening to start on their superior beer, wall-to-wall wisecrack volleys started up, and they never finished the evening sober. He envied them both their better beer and deeper laughter and thought their humour ‘ideally subversive of authority’.

A sense of carnival haunts this picture, and on the sea voyage to Cairo Frank had been enjoying Rabelais, whom the Russian critic Mikhail Bakhtin famously celebrated for his joyous subversion of authority and whose claim to write while drunk Frank thought credible. Indeed Frank asked his parents to send him a book by ‘my old friend Bakhtin’, which arrived disguised in a parcel of socks. Pretty as it would be to imagine Frank experiencing in Egypt the riotous ideals of Bakhtinian carnival, this Bakhtin was Mikhail’s brother Nikolai, who worked at Birmingham University and in 1935 published An Introduction to the Study of Modern Greek – the book Frank in Egypt devoured ‘at one gulp’ in the desert on Christmas Day 1941.

Young Frank admired these sergeants because they by day enforced the traditions of the army, and then at night mocked them, with a double conviction he could not rise to. Alcohol was everyone’s escape but had its dangers. One upstanding infantry officer with a weakness for ale who travelled out with Frank on the Pasteur he saw degenerating over fifteen months at a desert office desk into ‘the bleariest and bloatedest thing’ seen outside a circus; coming adrift from his regiment, he lost all sense of purpose. Frank when disheartened thought such purposelessness ran through the British army from top to bottom, but the ‘civilian soldier England is so good at producing’ helped him keep faith: the ‘best type in this diverse unit’. He was after all a prime example of this civilian soldier himself.

Frank early noted the contrast between the officer on campaign in the desert eager for a drink and a woman, contrasted with his desk-bound cousin surfeited with both. He believed that everyone had ‘the right to get bottled’ but celebrated in theory the ‘quiet dignity of the British soldier’ – always genial even when drunk – contrasted with the unattractive arrogance of drunken officers. His Marxism sentimentalised the downtrodden. In practice he ran out that August as orderly officer without hat, belt or even pips on his shirt, a none too genial bottle whizzing past his head, to help incarcerate ‘with pleasure’ six British bombardiers who were breaking up the Naafi. Not too much ‘quiet dignity’ in practice adorned this scene, which reminded him of a Chicago-style brawl.

Being tall, rangy, handsome and weighing in at some thirteen stone, he was mistaken more than once for an Australian, and so took a keen interest in their doings, finding Australians sober to be warm-hearted, humorous and democratic, but drunk both ‘charmingly child-like’ and ‘disgustingly brutal’. Those he met in Cape Town in April were beachcombing after missing their ships, having orgies of drunkenness, smashing cars and throwing pianos. A story from 1940 made him laugh: two aged Italians in their underclothes kept protesting vociferously after the capture of Bardia that they were generals. They were politely disbelieved until the police two days later picked up two drunken Australians dressed in full ceremonial kit as Italian generals. And six weeks in the Australian Hospital in Damascus that autumn would offer further opportunities for research. One Aussie orderly there, continuously drunk for three consecutive days, offered Frank brandy; Frank, noting that it was dangerous to decline an offer from a drunken Australian, none the less drew the line when this orderly sank to his knees.52

Even the Roman Empire under Hadrian had never flooded Egypt with such a cosmopolitan horde. Within days of arrival he counted fourteen nationalities on the Cairo streets including Palestinians, Czechs, French, Sikhs, Gurkhas, ‘Negroes’ [sic] and Maoris. He believed he could detect strength in the air. This note recurs. The following August after he had been posted far further afield, he thought the cavalcade of nationalities provided an epic spectacle: Greek and Yugoslav officers preening themselves on the streets of Alexandria, diminutive Iraqis in khaki among the white hollyhocks on the Persian frontier, Russians close-cropped and grinning, giving the V for victory sign, the Arab Legion, Poles, French Meharists in red-white headdresses, mounted on camels, and impressive Indian soldiers everywhere. He came to the conclusion that troops who had been out one year started to become denationalised, thinking of themselves less as Englishmen and more as Middle Easterners, even the ranks becoming to a certain extent declassed. Doubtless foreigners offered picturesque copy for letters home, but, besides that, this war was demonstrating beyond any hope of refutation, he felt, the unity of man.

On 22 June 1941, a corporal informed H Squadron that the USSR had that morning been attacked and was now Britain’s leading ally. Frank observed this news – coming so soon after the most recent disaster of the fall of Crete – being greeted with cautious optimism. He met that evening at Cairo’s Turf Club with Christopher Seton-Watson, whom he had known at school and New College, and Hal Lidderdale, an Oxford acquaintance and rival suitor of Iris’s. Egypt of course was full of old friends and acquaintances: everyone you had ever heard of passed through at some point in the war. They searched vainly for a wireless to listen to Churchill’s speech that night (‘The Fourth Climacteric’), declaring Hitler crazy and wishing on him Napoleon’s 1812 fate. Hal later recalled Frank ringing him up jokily in Cairo to propose a meeting: ‘Hallo: Joe Stalin here.’

It was not that he thought Stalin’s crimes mystically mandated by history: he refused to believe that the USSR could be such a corrupt and tyrannical regime as the papers said; and now he awaited impatiently a change of heart towards Britain’s new ally. He listed its virtues to his family. The government of the USSR – ‘whatever we say about its methods’ – was uniquely concerned with the welfare of its people. Goodwill rather than selfishness governed all its social relations. Working people were accorded honour and security and the talents of the arts and sciences were combined for public benefit. Russians enjoyed better entertainment than Hollywood, and their young were brought up with less jazz-addled minds. He read the now forgotten play Distant Point by Alexander Afinogenev (1904–41) set in Siberia in 1935. Its dialogue – trite and sentimental as it now reads – almost made him weep: ‘Tell them things are alright there – as they should be with Soviet Railwaymen’ and ‘Now let’s sit down comrades, – but in an organised way.’ It inspired him to write verse.53

There was mysteriously little sign of his brother-officers coming round to his point of view. Even one year later in July 1942 he met British officers who openly declared they loathed Russians more than Germans; and on entering a senior HQ to ask about publications on the Russian Army he was brusquely told to look under the Enemy Section.

He felt a deep emotional sympathy for what it must be like to be invaded by a ruthlessly cruel foreign army and he also felt an admiration that many shared, Churchill included, for the huge, self-sacrificial courage with which Russians were fighting. This went with a withering contempt for the Britain-can-take-it line: the best thing the English could do about the war was to keep quiet about it. While he sympathised with Britain’s bomb damage and food shortages, he did not think that, in comparison with what the peoples of occupied Europe and of Russia were undergoing – with the enemy on their own territory, starving, shooting and hanging their citizens – the British had much to complain about, and believed that their smug desire for self-preservation would make them unpopular after the war. The British were (at this stage) rotten propagandists, and Frank’s perspective was always pan-European and internationalist.

He longed to meet his first Russians but had to wait one further year and had meanwhile to make do with a subscription to the Slavonic Review, improving his Russian and translating Russian poetry, listening to Russian music – ‘one has not known sadness until one listens to Russian music’ – and cross-questioning ‘renegade’ Russian émigrés he met in Palestine who had left the Soviet Union in 1930, relieved to discover from them no flaws whatsoever in the country they had so mysteriously fled: ‘When [Russians] laugh it breaks your heart.’ He read War and Peace many times.

He praised all Slavs for suffering with such patience and courage, throwing their bodies between Europe and destruction. The Poles had suffered more than any other nation in Europe. Czech students had been shot in the street in cold blood; he tried to imagine that happening in Oxford. He had also read on the boat for the first time Marx’s Das Kapital and claimed that, so brilliant and polymath was it, Marx must have been the name of a syndicate: no single man could have been so erudite. He claimed that every word made him homesick for England – Marx’s classic land of industrial capitalism.

Frank’s relations with his batman for more than two years, Fusilier George Lorton, belong here – his closest and most representative ‘common man’. Only nineteen, a garage apprentice before the war, good-looking but anaemic, he drove while singing out of tune; Frank did not know how politely he could get him to stop. When Frank asked him while shaving whether he was looking forward to seeing Jerusalem, Lorton replied, ‘No, Sir.’ Frank lost his temper and told him he was a fool: it was a waste of government money ever taking him to the Middle East. Lorton reasonably replied that he had never asked the Government to do so. How was it that war enlarged Frank’s horizons, while narrowing Lorton’s? (As for Frank in Jerusalem, he thought that any other European people would have ruined Palestine quite as effectively as the Jews had, but, while disliking Zionism, he liked Jews.)

‘Fus. Lorton: for two years a faithful retainer,’ reads Frank’s caption.

Frank considered that Lorton on the whole bore his dull lot with quiet dignity, ‘lacking the background that officers had’ to help sustain him. He admired his mute ox-like endurance and in 1942 depicted him in the heat of Iraq, a rolled towel under one arm, fishing rod under the other, trundling Pooh-like to the river. In the evenings he shambled over to Frank’s tent to engage him in conversations about prop-shafts and differentials; his sole and entirely reasonable interest was improving his knowledge of mechanics against the future. Officer–servant friendships were doubtless the stronger for the many hardships shared. For his part Lorton would remember that he used to scold Frank for his untidiness, adding, ‘But I would have followed him to the end[s] of the world.’

Frank, so passionate and emotional in his advocacy, could be equally emotional in his criticisms, for even his naivety had limits. He thought Gorki’s political essays shocking pieces of newspaper propaganda. He once again wanted a generous and humane Communism of the heart, not a cold one of the head: ‘the only things that have any value today are love and courage’. He championed the ‘friendliness and warm sentiment’ without which socialism was cold and mechanical.54 So while he admired Sholokhov’s And Quiet Flows the Don he also regretted that a certain passion and irrationality were missing from Sholokhov’s materialistic picture of life. Though he told Désirée that, if non-cooperative, an individual should lose his rights, he also believed that only individuality keeps man immortal.

Above all, and despite all his hypothetical hatred of the British officer class, in practice his admiration for their courage and efficiency continued to grow. The theme gets into letter after letter. The Sassoonist attitude was plain wrong: blue-blooded officers, those fighting ‘to save the lunch-tent at Ascot’, were often the bravest of all. When he first saw copies of the Communist-inspired periodical Our Time, in which EP was involved, he scorned its predictable portrait of a high-ranking officer as a stereotypical ass. Frank, by contrast, had long strolled, straw in teeth, down a winding English lane of impulse and instinct, but very rarely found himself ‘wandering down the stream-lined autobahn of his socialist theory’.

Phantom feared that it might be disbanded as a white elephant, but slowly came instead to be understood as something between a commando and a signals unit, brought up to a strength of eight officers and eighty other ranks. They started with a six-week IWOS course (Irregular Wireless Operations School), which provided four motorbikes on which Frank’s men happily pulled on gloves, goggles and revved up, but which was rumoured to have ‘nasty ideas’ about desert-worthiness and to be training them for a forty-mile walk with only one halt and no water. The squadron was short-staffed and Frank wrote home in June: ‘Don’t laugh now, but I’m our maintenance & transport officer’ (or MTO). Though he put on his best big act in a pair of filthy overalls, a less technically minded MTO is hard to imagine.

At least in Egypt he came to enjoy motorbiking. On 27 June he celebrated some of the sights he and his bike had encompassed: ‘the delta in the evening with mixed choirs of frogs and crickets and black-white birds that fly like snipe or curlew; the desert at night, sweet and clean and dry and fathomlessly silent’. Some weeks later he found that in six days he had covered 1,100 miles, starting off with the morning sun peeping gingerly over the desert, singing lustily while the engine drowned the noise, and dead tired by evening: ‘the more I travel the more it intoxicates me’. By August he accounted himself a dual personality, being more suitably employed as intelligence officer as well as MTO.

Frank confided to his diary that ‘after two months of fucking around’ his squadron retrained through much of 1941. They were divided into five or six long-range signals reconnaissance patrols, each consisting of one officer and five men carrying a fortnight’s rations and 1,000 miles’ worth of petrol in two eight-hundredweight wireless cars and one fifteen-hundredweight truck carrying no. 11 wireless sets, which had a range of thirty-five miles. The arts of desert survival included the use of sand mats to extract your vehicle when bogged down, a canvas water-sack to keep the radiator cool, and navigating by prismatic compass and angle of the sun.

One ex-Commando officer who joined Phantom that August was Monty’s future liaison officer Lieutenant Carol Mather, by whom Frank at first felt cramped, but warmed to when he obligingly ‘mucked in’. This was not untypical: he had started by loathing his commanding officer Peter Forshall but grew very fond of him, and similarly with his successor Major Dermot Daly, whose friendship with Evelyn Waugh interested him. Frank was not unique in growing to like his opponents – including his political adversaries, if they evinced enough ‘heart’: no tales survive of his falling out with old friends.

Mather found Frank a delightful companion on a joint patrol to the Red Sea hills, camping out on the Gulf of Suez in which they swam naked, with the mountains of Sinai on the other shore, and speeding down the sparkling gulf next morning to the fabled Coptic monastery of St Anthony – the oldest active monastery in the world. Here he and Frank spent two nights in tiny whitewashed cells, their men outside with their vehicles. The monks fed them pigeon pie, and Frank and Mather got permission to swim in the cistern within the monastery’s five-acre enclosure. It was a gentle baptism into desert life and their last escape from reality, remembered by Frank as ‘one of the loveliest drives . . . ever’ and sixty years later by Mather for its complete otherworldliness.

Mather knew that Frank claimed to be a Communist, with a strong attachment to the war aims of the Soviet Union, but accounted it all light-hearted, and doubted whether he were a paid-up member. He thought Frank essentially a patriotic Englishman in love with the English countryside, and noted that his extraordinary scruffiness and untidiness of dress, through which he expressed contempt for the conventions, never stopped his being an excellent officer.

His parents fretted about how he might stay healthy in the Middle East, where Theo grew up and EJ served in 1916–18. A scare about bubonic plague at Mena closed the camp for days but happily proved unfounded. Frank sickened by other means. On 2 June ‘500, 000 devils chose my stomach as their battleground’. He spent 4–11 July in a long, curved and corrugated Nissen hut hospital in Ismailia with sandfly fever, debilitating but not serious, and his head like a turbine, appreciative of the nursing he got from the ‘thoroughly pleasant’ sisters. ‘Women are bloody marvellous, really, the way they manage to keep clean and neat and cheerful in an awful country like this.’ He tried to learn Arabic but it did not grip his imagination. A Cypriot and he competed to see who could swat more flies, Frank averaging a bag of 230 per day. Officers in hospital had the task of censoring the letters of all the other patients. Most communicated their wretched homesickness in ways that were second-hand and trite: ‘Cheer up Darling . . . We’ll meet again.’ But occasionally he found a Welshman – or someone who had read Shakespeare – and their eloquence in expressing the condition he too shared moved him to tears.

His sandfly fever was in July. That September his unit crossed into Syria via Palestine to gain wider experience in mountain country and ready themselves fast for desert warfare by October. Frank’s finger was throbbing, septic and swollen to the size of a banana; the squadron Orderly Sergeant Frank Jacobson lanced it for him. (Since Jacobson’s Communist opinions were known, the Sergeant later recorded that Frank didn’t associate with him too openly. But they knew each other well, did things together and he comes into this story later.)

Soon acute septicaemia affected his leg too. He wrote to EP, newly arrived at Cambridge to read history, that the tale of this trouble was ‘quite amusing’. He was up doing a job ‘in Muvver’s country’ when he noticed some nasty poison spots on his leg. He dropped into a field ambulance and came over queer with a temperature. First they suspected measles, then jaundice, then his leg ulcerated. The doctors themselves were falling ill with sandfly fever and jaundice and evacuated Frank by ambulance to the Australian Hospital in Damascus, which had a skin specialist.

Frank wrote a short story, ‘Picnic in Galilee’; and he claimed to EP to be working on a poem about the sufferings of Job, afflicted like him inter alia with boils, but the poem did not progress. Not till early November would they release him. Frank requested a bit of home news, the most fatuous jokes Dadza made in September or any outstanding example of Muvver’s fierceness. The Middle East was hopeless politically – no public-spirited middle class – and he jokily glossed the heading ‘MEF’ (for Mediterranean Expeditionary Force) as ‘Men England Forgot’.55

While communication at first could take months, so that Frank joked that there must be someone in the army post office whose brother he had kicked at school, airmail-letter speed gradually improved to mere days. He even received the answer to one cable he sent home that same afternoon, surely via Phantom’s ‘secret’ Cairo-to-Richmond wireless link. In early September Frank was angry at the prospect of being offered sickness-related home leave. Theo had discovered that two of Frank’s fellow officers had been sent home, the ailment of his commanding officer being, moreover, eczema. She was ‘ringing Generals’ like mad, neither for the first nor for the last time, and he wrote sarcastically that he expected at any moment to receive anonymous contributions to the cost of an artificial leg, his fever by now having ‘probably grown to the stature of the Black Death’. Besides, he wrote solemnly, one did not take sick leave when the fate of centuries was being fought out in Russia.

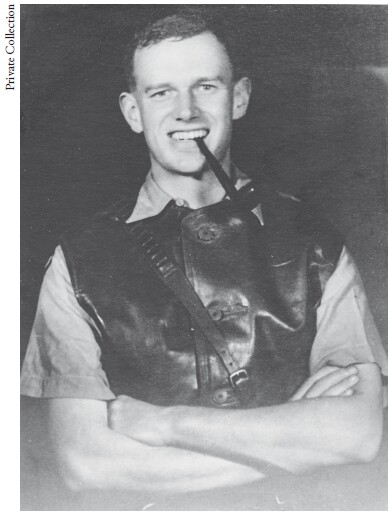

Here was a continuing source of irritation, and he tried to laugh away their fears. Remembering his family’s ‘insane desire for martial photos’ he sent them a ‘really tough photo’ of himself in a stout leather jerkin, hair cropped like a stormtrooper’s and a pipe clenched in his teeth. ‘Perhaps you’d like a close-up of me in a gas mask?’

Noting the plentiful guile in his make-up, he concealed from his family that his septicaemia had been serious enough to induce paralysis: for a while he was unable to move his limbs. There was also no occasion for him to disclose to them that, of the twelve out of his OCTU who in March the previous year had volunteered for the Middle East, by late 1941 two had been killed, one had died of typhoid, two had been taken prisoner, two more had been wounded and one disabled. Frank had longed to join them, but was deemed too young. Even the youngest was three years older than he was: had he been accepted, would he now too be under the sand? He naturally also withheld from his parents his despondency at how fast the death-toll of Wykehamists was rising, but did not keep from them that he was going into action, writing to them in November: ‘diarising up front is forbidden’.

‘Folks on high’ had from August taken a renewed interest in Frank’s unit, seeing that it had a role to play in the coming liberation of Tobruk from its long siege by General Erwin Rommel and his Afrika Korps. In late October Phantom mobilised at last. The delay caused by his long stay in hospital – ‘repair shop for men’ – separated him from his unit in the Western Desert and must have been doubly frustrating. It was probably in hospital that he found time and inspiration to write his best-known poem, which, one may surmise, slowly developed out of his musings about the virtuous Job’s sufferings and came to stand as both his own epitaph and – as has been noted – that of his entire generation.

As one who, gazing at a vista

Of beauty, sees the clouds close in,

And turns his back in sorrow, hearing

The thunder-claps begin

So we, whose life was all before us,

Our hearts with sunlight filled,

Left in the hills our books and flowers,

Descended, and were killed.

Write on the stone no words of sadness

– Only the gladness due,

That we, who asked the most of living,

Knew how to give it too.

As with his elegy for Rex, this poem is a single sweep of feeling. Once more, the reader feels intimately addressed by a solitary line of conventional reflection: Frank’s best-known poem’s wide appeal depends on its traditional values. Iris had commented that his own qualities of ‘simplicity tinged with melodrama’ could be felt in his poems. His language is indeed simple, but his prophetic rhetoric at last here transmutes melodrama into stoicism.

En route from his hospital on 17 November, Frank stopped for two hours at a staging-camp where the wounded were gathering to be sent home, before reaching Shepheard’s Hotel, that famous landmark, at midnight. Cairo in November was less nightmarish than in summer and there were more pretty girls about. He had three days before rejoining his unit in the desert. He was knee-deep in mail accumulated during his weeks away sick. The total bag for two months was six parcels, thirty-seven airgraphs,56 twenty-four letters, seven postcards and two telegrams. Too excited to sleep, he stayed up till four in the morning, eating olives and sandwiches, reading and re-reading his mail, seized with uncontrollable laughter, and writing a long, long letter home.

He compared his sensation to standing in a roomful of people all talking at once, eight of whom he wanted to embrace, another fifteen grasp by the hand, agree with, riposte or apologise to. What a remarkable, unbelievably lovable family they were and how lucky he accounted himself! And essentially a family of deep thinkers too! From Iris there were both letters and airgraphs: gloomy and, as always when she had not seen him for a long time, full of affection. He had evidently been denied that warmth in propria persona, and still had her ‘under his skin’. While giving his ‘folks’ a précis of all his correspondence he paused to commend to his father some ‘mysterious lines’ from Auden’s Letters from Iceland:

The tall unwounded leader

Of doomed companions, all

Whose voices in the rock

Are now perpetual,

Fighters for no one’s sake

Who died beyond the border.

These were in the direct line of English poetry, good not because by ‘poets who moaned’ but because they were by poets concerned with the English life around them. (What constituted the ‘line’ of English poetry was a hot Thompson family topic.)57 Like much in Frank’s story, this verse unwittingly predicts his own last weeks as the tall leader of doomed companions, fighters who also died beyond the border. This letter-storm had made him homesick for the English countryside and for his own set, ‘people with home woven ties and untidy hair whose ideas and emotions are in such a mess, but who know better than anyone how to make a friend and keep one’.

His mother sent a cheque for £10 to help him take sick leave. He declined the cheque and the chance of leave alike. Soldiers were commonly found later in Cairo going without home leave for five years. Frank’s schooling in the manly virtues would proceed uninterrupted. Bledlow itself, with its tension between his father and his fierce and manipulative mother – who every few months beckoned him home – would not see his return.

Like many soldiers he suffered sexual frustration: ‘any girl who catches me in the first month after I’ve landed will have me wrapped round her little finger even if she’s got a mind like a tuppenny thriller and a face like the back of a lorry’. His closest Winchester friend Tony Forster, also serving in Cairo, recalled his and Frank’s visits to the ‘murkier side’ of the city, though fear stopped them ‘sampling the fare’. As this was pre-penicillin such fears were wholly rational. Some 140,000 troops were stationed in wartime Cairo and there were seven separate VD clinics helping the unlucky with the consequences of queuing to enter brothels. Frank and Tony made indecent advances to two shoe-shine boys, but Tony thought they might be taken seriously and be up before the courts.

Frank, too, mentions visits to brothels where he once made sure no one knew he had French letters with him, evidently feeling divided – since a condom must have lessened the risks of infection – about whether he really wanted this shamefully functional form of release or not. He had also been hiding his condoms in base camp for fear of shocking his batman until young Lorton, hearing it claimed that he did not frequent prostitutes, protested with husky pride that he certainly did. On another occasion Frank spent no money ‘as I was stony broke. Chatted with repulsive Rosetta and her girls.’

He sounds somewhat at ease in this scene and would claim two years later to Iris Murdoch to have messed up his sex life by taking physical love far too lightly, condemned to the classic dichotomy of seeing women as whores on the one hand and unattainable Madonnas on the other.58 Two things are beyond dispute. He may not have died a virgin, but he did retain a certain puritanism; and, although he liked to flirt, he never experienced a physical affair with a woman whom he loved and admired.

EP was in this regard luckier. Theo that spring told Frank that EP was out of doors, that he was eating enormous meals and – with wholly unconscious ribaldry – that he ‘had been offered a mount at any time he wants it by a Mrs Clark (aged 30) who is running a small farm near by – horses & goats!’ Wendy Clark was nearly thirty-three and taught her three children the myth that EP, aged nineteen, came in to apologise for the damage he had done her cottage fence with a tank. In fact EP had just reached seventeen and was on a horse and cart when he called from nearby Biddesden Farm and met the remarkable Wendy who, as Theo believed, ‘worked on the admiration of young men’, her seduction technique including the fiction that she ‘suffered from a serious ailment’ and so needed physically to be comforted. Their affair helped EP’s confidence and he appreciated her hospitable, bohemian household – ‘a kind of alternative society through which all kinds of gifted people flowed’, including Leslie Baker, devoted friend to Katherine Mansfield. EP’s friends were welcomed too. When Theo in 1943 learned the nature of their relationship – the year EP was stationed abroad in North Africa – she ‘went on the war-path’ and confronted Mrs Clark, who held her own.

Wendy Clark with husband Geoffrey and children Francis, Helen and Miles, plus sheepdog, Robin, 1941.

But Frank did not have his brother’s luck. He agreed that he must surely be a prude on noticing how much he disliked the ‘S and M’ in Hemingway’s stories: why write about a well-to-do man dying of gangrene only because he failed to take proper precautions (‘Snows of Kilimanjaro’)? Why depict a woman facing an abortion for the sole reason that she has been careless (‘Hills Like White Elephants’)? Then he disliked Robert Jordan in For Whom the Bell Tolls winning a friendship by telling a story ‘obscenely discreditable’ to himself. Hemingway’s perverse mentality was on display. Or was Frank himself, he wondered, just a little old-fashioned? Yes, he was. Though famously ribald himself, he found Tristram Shandy too bawdy and digressive: there was a distinction between what he allowed himself to say and the dispensation he permitted others.

He could never stand a love story unless it was an integral part of the plot, and in his own case a love affair did not seem part of the plot. He bared his soul to Désirée Cumberledge, commending his parents to her – ‘Drop in on Bledlow. If I’m written off, be sure to. You’ll find they know all about you’ – and commending her to his parents: ‘Girl in a million, wish you could meet her, if she wasn’t a pacifist I’d want to marry her.’ When Désirée announced her engagement in a mere cursory airgraph her casualness disconcerted him. Yet she had been virtually engaged before until the poor boy was killed flying over Germany, and he wished her better luck this time. (She never found it. She died unmarried aged seventy-two in 1992, an active Anglican and retired schoolmistress. Among her possessions were many letters from Frank.)

He certainly did not want to marry the jovial daughter of some hunting squire ‘or any woman who wasn’t fully as charming as Tolstoi’s Anna or Natasha or Kitty or Princess Mary’, a half-joke suggesting that his habit of idealising women died hard. In his more sober moments he liked to consider himself a lifelong bachelor. The ‘very long and cheerful letter’ that he posted to Iris Murdoch that June of 1941 has not survived: Iris, writing briefly to Theo to share news of his arrival in Egypt, admired his ‘genius for finding all experiences fascinatingly interesting’. In September she wrote to him to say that she liked the ‘sweet verse’ he had sent her. She was happy that many friends had followed him to Egypt, including Leo Pliatzky. He wrote to her again on 10 and 21 November.

In Shepheard’s Hotel he carefully packed all he needed into one kitbag, a slim bedroll and a haversack. He left behind in one suitcase at a ‘base dump’ all the letters he had received since arrival and in Cairo itself two suitcases and a tin trunk containing his diary, poems and short stories. While it was ‘one hundred to one against’ these ever reaching his family without him, if that happened he apologised in advance for how shockingly badly written his diary was – he had simply logged interesting, amusing sights and lovable and strange characters for future use, perhaps in a novel, with no time to mould each entry into the artistic unity that he thought one of the chief joys of diarising. This is, by the way, overly modest: he secreted fluent prose without apparent effort.

In his best epitaph Frank pictures his generation leaving behind their ‘books and flowers’. From his own small library of seventy-five books he carefully selected fourteen to take into the Libyan Desert. Some he slipped into his service dress tunic. You never knew when you might get stuck with nothing to do – as had just happened during his two months with septicaemia. His selection included Moll Flanders, Gorki’s 1907 novel Die Mütter (which he loved despite being unable to find a copy except in German), Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls, Three Men in a Boat and some books in Arabic and Italian together with dictionaries for those two ‘languages of most immediate value’: they were after all about to fight Italians as well as Germans.

He caught his train from Cairo at midnight on 21 November ‘in one of those inspired scrambles’ that featured prominently in the life of the Thompson family. He had not merely lost his travel warrant but forgotten to bring provisions or water bottle. By the time he rejoined his unit, Phantom had undergone adventures. First was the threat by the Eighth Army’s Brigadier Jock Campbell, never forewarned of their arrival, to have the whole outfit arrested as spies. Happily one patrol, led by the acutely short-sighted Edgar ‘Herbie’ Herbert, secured the squadron’s first prisoners by shooting at what Herbie took to be gazelle, only for them to put up their hands and surrender – because they were in fact three Germans on a motorcycle combination. Then Carol Mather’s patrol was charged with the task of simulating the signal traffic of an armoured division attacking from the south near Jarabub; for four wearisome days they concocted and transmitted bogus messages on the air, to try to dupe Rommel’s spies.59

The Allied relief of Tobruk after its 240-day siege on 27 November followed nine days of fighting and was first reported to HQ by Phantom. By the 23rd Frank had rejoined his unit, deploying with the 17th Indian Brigade. This was his longest single stretch in any one country – five months from November 1941 to April 1942 ‘beneath the Libyan dog-star’, as he expressed it lyrically to Iris Murdoch. The phrase was not just romanticism: at night in total blackout they navigated using Sirius (the dog-star) and once, as Frank reported, ‘steering slightly to the right of the moon’. The experience was hallucinatory, with camel-bushes only at dawn finally losing the shape of ambushing marauders. They drove in close convoy in choking dust; the vehicle in front often stopped when its driver fell asleep at the wheel.

Now at last he saw action and came under fire. On 25 December Benghazi fell, one of its deserted Italian villas soon providing Frank with a flea-ridden billet. His stock of books there had increased to twenty-two, swollen by the occasional volume reaching him from home.60 Frank’s collection now also featured three captured German novels; and here was one tiny sign that the fortunes of war at last were changing.