CHAPTER 3

The Traffic in Slaves

In one house [in Valencia in the 1490s], I saw men, women, and children who were for sale. They were from Tenerife, one of the Canary Islands, in the Atlantic Ocean, who, having rebelled against the King of Spain, were in the end reduced to obedience. . . . [A] Valencian merchant . . . had brought 87 in a boat; 14 died on the trip and the rest were put up for sale. They are very dark, but not Negroes, similar to the North Africans; the women, wellproportioned, with strong and long limbs.

– –Hieronymus Münzer, fifteenth century

The Slave Trade

The slave trade lasted throughout the Middle Ages and the early modern period, in both Christian and Muslim areas, even though birth and capture in war and raids produced more enslaved people. Yet the categories of trade and capture are hard to separate, for many of the people traded as slaves in Iberia had originally been born free and had been enslaved during war or in raids far from the peninsula. Some came from as far away as the Russian rivers or Africa south of the Sahara. Others traveled only a few miles as they crossed the religious frontier in the Mediterranean or in the peninsula or simply moved from town to town under the control of slave dealers.

Those captives of war and raids who were not ransomed came to be slaves, as we saw in the previous chapter, and over time their chances for regaining their free status and their homelands diminished or faded completely. They had virtually no status in the new society. Some scholars have even called such unfortunates the “living dead” because of their social and legal isolation.1 They found themselves cut off from the people and things they had known from birth, and soon lost what they might have brought with them, such as their clothing and their accustomed foods. They held on longer to other ties to home: their religion and their language. Much depended on their ages, for those captured and enslaved as children remembered less than adults. Whatever their origins, they all began to acquire, slowly and painfully in some cases or more easily in others, familiarity with and a stake in the households and societies of their masters.

Roman Spain did not have a highly developed slave trade, though the defeated populations of some towns ended up as slaves and were exported from the peninsula. The Visigoths did not enslave the conquered Romans and provincials in a wholesale fashion, and domestic warfare did not usually produce slaves. The Visigoths, like other Germanic groups, were reluctant to enslave members of their own group, even though they did allow fellow Visigoths to fall into slavery for debt, criminal sentence, and self-sale. As the Visigoths looked outside for slaves, the ethnic and religious divisions present in the regions they conquered simplified their search. The Arian Christian Visigoths enslaved those they captured in their wars against the Catholic Franks. The Franks did the same, and large numbers of Arian captives entered the slave markets of Gaul. Arian and Catholic Christians could make slaves of pagans and Jews, and slave traders always brought slaves from distant lands. Pagan slaves from central Europe and from North Africa reached Spain as early as the mid-sixth century. There was a slave trade from Visigothic Spain to other parts of Europe and North Africa, but not much is known of it. Merchants sold slaves from Spain outside the kingdom, including some kidnapped children, even though there were some prohibitions on the export of slaves.2

The Islamic world experienced a golden age during its first centuries, and Muslim Spain shared fully in it. Once the bounds of the Islamic world were set, there were no more slaves to be obtained legally within the frontiers, except for rebels and the children of slaves. War produced relatively few slaves, and consequently the slave trade gained great importance. The Muslim elite acquired great riches and preserved that wealth through many generations. Thanks to the economic advantages that that they possessed over their neighbors, they could afford to import what they needed and wanted from outside. The necessities included timber for fuel and construction, metals (iron and gold above all), and slaves, who formed an important component of the vast new commercial system and who were considered necessities by large numbers of Muslims.3 Even though slaves seldom worked in agriculture,4 they still were imported in large numbers for artisan labor and domestic and military service. One indication of the volume of the slave trade comes from Córdoba. That single, albeit brilliant, city may have had nearly 14,000 slaves under the caliph ‘Abd al-Raḥmān III in the mid-tenth century, when the total population may have reached 250,000. 5

The early period of the slave trade into al-Andalus is not fully documented, though the outlines are fairly clear. Even at the beginning of the conquest, the Muslims brought slaves and free servants with them. These included Ethiopians and Armenians, Egyptians and Nubians. In the ninth century, merchants brought slaves into al-Andalus from Christian Iberia (at that time the northern fringe of the peninsula) and other parts of Europe. Many of the slaves were pagans captured in Central and Eastern Europe, and others were Christians, captured in Muslim raids in France and northern Spain. The merchants included Christian Franks, who dealt in the European pagans, and Muslims and Jews, who dealt in Christians. The enslaved people who found themselves traded into al-Andalus could spend their lives there as slaves, or they could face more distant journeys to other parts of the Islamic world, for there was a lively re-export trade.6

Before the tenth century, the Muslims of Spain generally bought Christian Europeans as slaves, adding them to the descendants of indigenous slaves conquered in the eighth century. By the tenth century, the mostly pagan Slavs became the most numerous imported group throughout Western Europe, where their ethnic name became the origin of the word for “slave” in most Western languages, as we have seen. The Muslims used the term ṣaqāliba in Arabic, still another example of a newly coined word for slave derived from “Slav.” But ṣaqāliba were brought to Spain by slave dealers from any of a number of European origins: Central Europe (brought in via Verdun), the shores of the Black Sea, Italy, southern France, and northern Spain. Byzantine Christians, captured by other Muslims in the eastern Mediterranean, were present as slaves of the Spanish Muslims by the eleventh century, along with North African Berbers enslaved following unsuccessful revolts.7 Some were brought into Spain as eunuchs. Muslim Spain was well known for the presence of eunuchs and for their export to the markets of the Muslim Mediterranean. Young boys among the captives were castrated and then fetched high prices as eunuchs. Some of the slaves were castrated in Verdun and then taken to Spain. Others were made eunuchs in Muslim Spain.8

The rulers of Muslim Spain began to recruit foreigners as soldiers in the eighth century. The history of slave soldiers in the Islamic world is complex, although the basic motivation for their use was simple: they were loyal, with no local ties to compromise their loyalty to their masters. They came from North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, and Europe, with the “Slavs” (Europeans) the most important group among them. They were brought in as children, converted to Islam, and given an education in Arabic. The real rise in their military use came with al-Ḥakam I (ruled 797–822), who organized a permanent force of salaried and slave soldiers. Al-Ḥakam II (ruled 961–76) made use of Slavs and had a unit of black soldiers as his personal guard. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān III, who declared himself caliph in 929, began to import and to employ Slavs on a larger scale. By the time of his death, their numbers in Córdoba are put at 3,750. The number of Slavs increased still more under the chamberlain al-Mansur (978–1002). The inhabitants of Córdoba, who dubbed them “the silent ones” because of their lack of proficiency in Arabic, regarded them with suspicion. Many of them attained freed status and formed families. Their presence disrupted the balance of ethnic forces in the caliphate and hastened its decline. Their role declined with the end of the caliphate in the early eleventh century, when many of them migrated to certain of the taifa kingdoms, the city-states that replaced the unified caliphate, where they eventually became rulers of Almería, Badajoz, Denia, Mallorca, Murcia, Tortosa, and Valencia. The trade in Slavic slaves virtually ceased, but slaves imported from sub-Saharan Africa rose in numbers and came to constitute a significant element in the slave trade to al-Andalus.9

The Muslims of Iberia obtained black African slaves through their connections with their coreligionists in North Africa. Muslims called the black Africans ‘abid (plural of ‘abd = slave) or sūdān. The latter term came from their place of origin south of the Sahara in the Bilād al-Sūdān, the land of the blacks, where the Sudanic belt of grasslands stretches eastward from the Atlantic Ocean to the Ethiopian highlands. Muslims had been familiar with the peoples of sub-Saharan Africa since they initially crossed the desert in the first Islamic century and brought back a few slaves. Their numbers grew as Muslim penetration into sub-Saharan Africa intensified. The North Africans from the eighth century maintained caravan routes across the Sahara to trade in the black states of the Sudan, many of whose leaders and merchants had converted to Islam. The North Africans provided the sub-Saharan markets with dates, figs, sugar, and cowries (shells for use as currency). Manufactured goods were quite important: copper utensils, ironwork, paper goods, Arabic books, tools, weapons, and cloths of cotton and silk. The Sudanese had cotton cloth of their own, but imported dyed fabrics had an appeal for them. Jewelry, mirrors, and glass, especially Venetian glass, went south with the caravans. North African horses were in great demand south of the Sahara, because the military strength of the Sudanese states depended on cavalry. The North Africans also provided salt that they purchased along some of the caravan routes.10 In exchange, sub-Saharan Africa provided the North Africans with ivory, ostrich feathers, skins and leather, kola nuts, ebony wood, and a type of pepper. Nevertheless, gold and slaves were the most important exports from the Sudan to the Mediterranean. By the end of the eighth century Muslims already knew of the gold from the region. From the tenth century through the fifteenth, the Muslims and Europeans obtained much of their gold from West African sources by way of the trans-Saharan trade routes. The merchants and rulers of the Sudanic states grew wealthy and powerful as a result of their ability to supply the metal and thus to pay for their imports from the Maghrib.11

The Muslim world had a constant demand for sub-Saharan slaves that continued through the Middle Ages and long after 1500, even maintaining maintained a sizeable volume during the period of the trans-Atlantic slave trade.12 The sufferings of those who were forced to make the trek were horrifying. In addition to the heat and cold, the threat of storms, and the lack of water that they shared with the other members of the caravans, the slaves often had to act as bearers of other goods. Even when they did not carry loads themselves, they had to load and unload the camels and help with the daily camp preparations.13 The slaves who survived the desert crossing spread through North Africa, where many remained. Others were sent on to other Muslim lands, including Islamic Spain, but until the fall of Granada in 1492, most slaves of the Spanish Muslims were Christians from the northern kingdoms of the peninsula.

The Slave Trade in Christian Spain

The trade in slaves went both ways, of course. Iberian Christians imported slaves throughout the period as well, just as their Muslim contemporaries did. The slave trade changed over the centuries as the political and military balance shifted. The Muslim ascendancy from the eighth into the eleventh century declined as the Christians gained greater and greater control from the eleventh century to the end of the fifteenth.14 Those who operated the slave trade changed as well. Among the slave traders supplying Muslim Spain, Muslim and Jewish merchants predominated in the early period. Sale documents indicate that Christian merchants tended to replace Jews in the slave trade, beginning in the twelfth century.15 Large populations of free Muslims came under Christian control after the thirteenth-century conquests of the south. Consequently, free Muslims were more numerous than Muslim slaves, who appeared more frequently in the frontier regions and less often at greater distances from the frontier. By the eleventh century, some black slaves began to appear in the Christian regions of the Mediterranean. In 1067, as one example, the Christian Arnallus Mironis and his wife Arsendis donated ten black captives to Pope Alexander III.16

Within Christian Iberia in the later Middle Ages, the lands of the Crown of Aragon were closely tied with the currents of Mediterranean trade and the slave trade, whereas the Castilian kingdom tended to supply its demand for slaves through war and conquest. Slave owning by non-Christians continued in the Crown of Aragon, although in a restricted fashion. Neither Jews nor Muslims in post-conquest Valencia could hold Christian slaves. Muslims could own Muslim slaves, but there was a constant attrition as Muslim slaves gained manumission or accepted baptism and left their Muslim masters. The laws of Valencia explicitly stated that the non-Christian slaves of a Jewish master would be free if they converted to Christianity. By implication, the same would apply to slave converts owned by Muslim masters. Local Muslim slave owners could not make up the losses. After the conquest, the Muslims were cut off from the Muslim slave trade, and their economic situation worsened, making them less able to purchase slaves from Christian suppliers, who used legal and extralegal means to increase the supply of Muslims to put on the market. Merchants from the Crown of Aragon took slaves to southern France, and Muslim envoys who visited Barcelona often bought Muslim slaves there.17

Many Muslim slaves entered the market after being captured in the conquests of King Jaume I, when Valencia and the Balearics came under Christian control in the early thirteenth century. Thereafter, things changed. The late medieval commercial and imperial expansion of the Crown of Aragon in the Mediterranean coincided with the period in which it was less possible to secure slaves within the peninsula. Slave recruitment shifted as a consequence. Piracy and the slave trade fed medieval slavery in the Crown of Aragon.18 Throughout the thirteenth century, Muslims made up the bulk of the slaves; some were captives of pirate raids and from the Castilian raids on the Muslim kingdom of Granada. In the thirteenth century, too, documents began to show distinctions among the Muslim slaves—white, brown, olive—which indicated recruitment from wider areas than before.19 By the fourteenth century slaves of other origins came into the Iberian Mediterranean.

Then the Black Death hit. A great pandemic came to Europe from Central Asia, crossing to the areas around the Black Sea by way of the caravan routes opened by the Mongols and reaching the Crimea in 1346. Two years later it entered Italy by way of Constantinople. From Italy it spread throughout Europe, causing the deaths of a third or more of the European population in a period of three years.20 Among the catastrophic consequences of the plague was an increase in slavery, as local free survivors of the plague could demand higher wages and better working conditions. Those who sought servants and manual laborers turned to buying slaves. In the Iberian slave markets of the later fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, more women than men appeared. This set of facts fits well with the Italian evidence for the period that points to a strong growth of slavery, especially domestic slavery, following the Black Death.21

New sources of slaves began to supply the markets of Catalonia and Valencia, whose merchants were active throughout the Mediterranean and into the Black Sea. They, together with Italian merchants, brought slaves from distant regions to Barcelona and other cities. For a time in the fourteenth century, Greeks appeared in the Crown of Aragon as slaves. Their presence was due to the Catalan freebooters called the Almogávares and their conquests in the Balkan Peninsula. The Greeks, however, were Orthodox Christians. Efforts by church officials in Rome and Barcelona freed many of them and eventually stopped the trade, on the grounds that Christians should not enslave Christians. By the fifteenth century, another reason for the end of the trade in Greek slaves was the decline of Catalan influence in the Balkans.22 The slave trade from the eastern Mediterranean diminished by the late fifteenth century, as the Ottoman Turks consolidated their control in the region.

Sards came on the market in relatively small numbers during the early fourteenth century, when the Crown of Aragon was taking over Sardinia. Theoretically Sards were subjects of the Aragonese king, but those who resisted the conquest and those who later revolted against the conquerors could be enslaved.23 In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Italian merchants brought back Albanians, Tartars, Russians, Caucasians, and other Crimean peoples. Albanians also fled from the Turkish advance in the Balkan Peninsula in the 1380s. Some, in desperation, sold themselves into slavery and ended up in Venice, from where dealers transported some of them to Mallorca and Catalonia. Turks and Armenians appeared among the slaves of the Crown of Aragon, but they were only a small proportion of the total numbers.24 The town of Vic in Catalonia, isolated from the sea and from the frontier with Islam, had slaves from a surprisingly varied set of origins in the early years of the fifteenth century. Of 39 slaves sold in that period, 14 were Tartars, 7 “Saracens” from either Spain or North Africa, 6 black Africans, 2 Circassians, 2 Russians, a Canarian, a Bulgar, and a Bosnian.25

To move to the center of the peninsula, slaves in Castile were almost exclusively Muslim in origin during the twelfth, thirteenth, and fourteenth centuries. Before the fifteenth century, Castile was not greatly involved in Mediterranean activity and purchased few slaves from Mediterranean merchants. Thus only small numbers of slaves from the Mediterranean reached Castile. Rather, Castilian slavery was fed by the reconquest and the raids into Muslim territory, and, within the territories under Castilian rule, Andalusia was the most prominent location where slaves were used.34 In Cádiz at the end of the fifteenth century, there was a sizeable number of slaves, both because many citizens of the town owned a small number of slaves, and because many Muslim slaves passed through Cádiz before being sold elsewhere, notably in Valencia. In Cádiz, too, we see evidence of a few Jews sold as slaves.26 On increasingly rare occasions, slaves from Eastern Europe could find themselves in Andalusia.27

The slave trade in Canary Islanders had a relatively short existence from the fourteenth to the sixteenth century. When individual European captains with authorization from the Castilian monarchs undertook the conquest of the Canaries in various phases, they found the islands inhabited by natives akin to the Berbers of northwest Africa who were living at a Neolithic level of culture. They likely had lived in isolation from the rest of the world since the end of the Western Roman Empire, a thousand years before. Politically they divided themselves into smaller or larger bands, and the Castilian conquests proceeded by securing treaties with some of the bands and conquering others. The settlers in time remade the Canaries along the lines of Europe, with cities, farms, and sugar production facilities, but in the initial phases of the conquest the conquerors resorted to enslaving natives as a quick way to make the profits necessary to repay the loans to pay for their expeditions, mainly financed on credit. Only natives of the conquered bands could be enslaved legally, but the royal agents had to maintain constant vigilance to ensure that the conquerors did not violate the rules and enslave members of the treaty bands.28 But there was a loophole. If members of allied bands rebelled or refused to carry out the terms of their treaties, they could be enslaved as “captives of second war” (de segunda guerra), as we saw earlier. Many enslaved Canarians were sold on the mainland, whereas others remained in the islands and found themselves put to work by the Europeans. The material and legal conditions they lived under resembled, not surprisingly, those of the slaves in late medieval Spain.

Natives of the Canaries did not make a substantial or a long-lasting addition to the international slave trade and did not even fill the labor needs of the Canaries. The indigenous Canarian population was small to begin with, and the isolated island peoples fell victim to diseases common in Africa and Europe. Manumission was common for those who did become enslaved. The Canarian slave trade to Europe ceased early in the sixteenth century, as the remaining Canarians increasingly assimilated European culture and intermarried with the colonists. Other sources of labor were necessary before the islands could be developed fully. So the Canaries witnessed the influx of other laborers, including a number of free Castilian workers. More substantial settlers often brought their own slaves with them. Berbers and black slaves were obtained from Castilian raids and trade along the West African coast, or brought to the Canaries by Portuguese dealers. In the course of time, slaves came to be born in the islands. For a short period after the first Spanish contact with the Americas, Indians were sold in the Canaries. Their numbers were always few, and the trade soon stopped when the Spanish monarchs outlawed slave trade in Indians.

Black African, Muslim, and Morisco slaves came to constitute a significant component among the work force in the Canaries. The settlers in the Canaries acquired imported slaves in a variety of ways. Some slaves, who had already spent time in Spain, accompanied their Spanish owners when they migrated to the Canaries. Portuguese merchants sold others from their ships as they stopped in the Canaries on their return voyages from West Africa. Castilians competed with Portuguese in the trade, especially during the war between Castile and Portugal from 1474 to 1478. By the treaties ending that war in 1479, Portugal received a monopoly on trade with Africa south of the Canary Islands, but illegal Castilian raids continued into the sixteenth century.29 Castilians engaged in raids called cabalgadas mounted from the Canaries, and along the African coast north of Cape Bojador they acquired captives and cattle. Manuel Lobo Cabrera found records for 154 raids from the eastern Canaries during the course of the sixteenth century. The greatest number (87) left from Lanzarote, followed by Gran Canaria with 59. Only 8 left from Fuerteventura. At times, the raiders acquired black slaves directly, although often a more complicated process ensued. Most of the human booty from the raids consisted of Muslims. Some were enslaved, converted, and later freed. Other Muslim captives, those who were able to do so, negotiated for their ransoms, and frequently they paid for their ransoms with variable numbers of black slaves. This became one of the most common means by which sub-Saharan Africans entered the islands.30

Castilians also went at times from the Canaries to the Cape Verde islands, where they could purchase African slaves directly from the Portuguese residing there. From the Canaries they also circumvented the Portuguese by going to Senegambia and the Upper Guinea coast to acquire slaves. This trade was illegal until the union of the Spanish and Portuguese crowns under Felipe II. The slaving expeditions to black Africa were always less frequent than the cabalgadas to Muslim-controlled North Africa. Over the course of the sixteenth century, some 25 expeditions from Gran Canaria went to black Africa, whereas 59 went to Barbary. It has been estimated that from all sources, some 10,000 slaves were brought to Grand Canary Island during that century, and that slaves represented some 10 to 12 percent of that island’s population.31

The Portuguese were the main slave traders of Europe in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, even though Spaniards operating from Andalusia and the Canaries acquired some black slaves and brought them to Spain. In the first decade of the Portuguese African slave trade, ca. 1434–1443, the Portuguese often raided for slaves along the Saharan coast, but they soon came to realize that purchasing slaves was more acceptable to the local African rulers and that trade also made better economic sense. The chronicler Azurara described the scene with a mixture of complacency and pity, as a group of slaves arrived in Portugal in 1444.

And these, placed all together in that field, were a marvelous sight; for amongst them were some white enough, fair to look upon, and well proportioned; others were less white like mulattoes; others again were black as Ethiops, and so ugly, both in features and in body, as almost to appear (to those who saw them) as images of the lower hemisphere. But what heart could be so hard as not to be pierced with piteous feelings to see that company?32

To exchange for the slaves along the African coast, the Portuguese took goods from Europe and some from Morocco, including horses, cloth, saddles and stirrups, saffron, wheat, lead, iron, steel, copper, brass, caps, hats, wines, wheat, and salt. In return they secured gold, especially at the trading center at São Jorge da Mina, and a variety of exotic luxuries to be sold in Europe: slaves, animal skins, gum arabic, civet, cotton, malaguetta pepper, cobalt, parrots, and camels.33 Portuguese slave trading soon became more complex, as traders took slaves from several places on the West African coast to markets where they could be sold. These included the Portuguese colonies in their own Atlantic islands, the Canaries (as we saw), and Portugal itself. Perhaps surprisingly, they also sold African slaves from farther south to the local African rulers and merchants at São Jorge da Mina. Part of the African demand for slaves at Mina came from the African merchants, who needed bearers to carry the bulky imported goods from the coast to the interior. To meet the demand at Mina, the Portuguese took slaves there from the region of the Niger Delta and used them as part of the price they paid to buy gold from the local merchants. Portuguese slave traders also provided slaves to satisfy the labor needs of the new Portuguese plantations in Sao Tomé, the Cape Verdes, and the Madeiras. The Portuguese sold other slaves to Castilians in the Canaries or on the mainland. Only a minority of the African slaves who fell victim to the Portuguese slave trade actually arrived or remained in Portugal. Merchants later exported significant numbers of them to other parts of Europe, particularly to Spain and Italy.34

The black African slaves included people from various ethnic groups in West Africa. Spaniards and Portuguese of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries referred to the place of origin for many sub-Saharan slaves as “Guinea,” a word that passed into English. It probably derived from a corruption of the name Jenné, a principal trading city just south of the Sahara. The area called Guinea corresponded to modern Senegal, Gambia, Guinea Bissau, Guinea-Conakry, and parts of Mali and Burkino Faso. Other slaves came from the Kongo kingdom and Angola, as well as from the Cape Verde Islands, though most of them had been captured on the mainland. The slave trade expanded significantly into new areas. Up to about 1550, most were Mandinga and Jolofs/Wolofs, and as the century progressed more and more came from Kongo and the islands of Santo Tomé and Cape Verde.35 These latter islands were entrepôts, and slaves from many regions came to be assembled there.

The Portuguese had royally chartered factories at Arguin, Ughoton, and elsewhere, in addition to Mina. There the exchanges were conducted between the royal officials on the spot and the ships’ officers. At places other than the factories, the crews dealt directly with local African merchants and rulers, or with go-betweens. Crown regulations specified treatment aboard ship, but there were problems of food, water, clothing, and shelter that could cause disease and death for the slaves. Those who died en route were dumped overboard. Chains and manacles were available to control the recalcitrant, but insurrections did occur. In 1509, for example, a group of slaves from Arguin tried unsuccessfully to take over a slave ship.36

The Portuguese slave trade had a rather loose organization during the first four decades of its existence. Shipmasters needed special licenses to make the voyages to Africa, and on their return they had to pay a certain percentage of their profits to the royal treasury or to a royal designee. They could unload and sell their cargoes in various Portuguese cities, usually in the south. By the 1460s the trade was becoming more lucrative, and, as tighter regulation seemed essential, the king in 1474 assumed full control over the trade with the West African region. Gradually, the Portuguese royal officials began to center the administration of colonial trade in Lisbon, although slaves could still be unloaded in Setubal and some ports of the Algarve. From the 1480s the Lisbon House of Slaves, the Casa dos Escravos de Lisboa, administered the trade and collected the royal dues, under the direction of a royal official, the almoxarife dos escravos. His deputies met each ship arriving in Lisbon from Africa to inspect its cargo and records. Once that was done, the fettered slaves were led through the streets to the House of Slaves. Located near the Lisbon docks, it contained a prison for confining newly arrived slaves before they were sold, offices for the administrators and record-keepers of the trade, and a cooperage for the construction of casks and barrels needed for royal vessels. Officials would assign a price based on the variables of sex, age, physical condition, and health. Individuals or wholesale contractors (corretores) purchased the slaves and sold them in the public slave market of Lisbon or transported them elsewhere.37

It is virtually impossible to determine accurately the numbers of slaves involved in the Portuguese slave trade back to Europe. As we have seen, the vessels that loaded slaves in West Africa did not bring all their cargoes back to Lisbon, despite royal efforts to centralize the trade. Many ships stopped off in the islands and disposed of some slaves there; others unloaded in Portuguese towns south of Lisbon; while others still sailed directly for Seville and other ports of Andalusia. A. C. de C. M. Saunders estimated that from 1441 to 1470 up to one thousand slaves reached Lisbon yearly, and that from 1490 to 1530 between three hundred and two thousand slaves annually were brought to Lisbon.38 Ivana Elbl estimated that the Atlantic slave trade from West Africa to Europe and the eastern Atlantic islands was 156,000 in the period 1450–1521.39

The Portuguese brought a few Indians from the subcontinent to Iberia. We can see the geographical trajectory of two such slaves: the slave Rodrigo in his mid-twenties from Calicut sold in Málaga in 1511 and the fourteen-year-old Francisco Enrique, a Muslim also from Calicut, brought to Iberia by a Portuguese merchant and sold in Córdoba in 1519.40

Functions of the Internal Slave Market

Whatever their origins and by whatever routes they reached Iberia, slaves were merchandise in the slave markets of the peninsula. We have little evidence of the markets of Roman and Visigothic times. In al-Andalus, as elsewhere in the Muslim world in the Middle Ages, most slaves were sold in the urban markets. In them, the market’s governor regulated slave merchants and their transactions. Special women clerks oversaw the welfare of the women slaves and prevented them from being used as prostitutes while awaiting sale.41

In the late medieval Crown of Aragon, dealers sold slaves both privately and publicly. When slaves first arrived in both Barcelona and Valencia, they were often sold in the streets and squares. In Barcelona, traders exhibited their wares in the morning market in the Plaça Nova and all day in the Plaça Sant Jaume.42 Other recent arrivals and slaves being resold were shown to buyers in private houses owned or rented by the sellers. The government of Valencia regulated and taxed the slave trade, and consequently Valencian archives house a fund of documents revealing the varied facets of slave life and conditions in that kingdom. More information about the internal slave market is available for Valencia than perhaps for any other city of the Christian Mediterranean. Valencia reflected the older pattern of slavery in the medieval Mediterranean, unlike Seville, which came to fit the pattern of Atlantic centers. If slaves were not as numerous in Valencia as they were in Seville, they were more varied in their ethnic origins. The bulk of the slaves there were Muslim in origin, either from the kingdom itself or from North Africa. There were also other slaves from other provenances present in Valencia, brought there via the established slave trade routes.

Merchants with slaves to sell used Valencia as their favored market in the Crown of Aragon. With the fifteenth-century decline of Barcelona, Valencia became the most important commercial center on the peninsula’s Mediterranean coast. Valencians made up about a third of the dealers, and the rest included merchants from other parts of the Iberian peninsula and from various Italian cities. The dealers first rested their newly imported slaves and then displayed them publicly. Before slaves could be sold, the chief bailiff (bayle general) had to register them, and that official collected the royal tax of twenty percent on the sale of slaves. At the time of sale and long afterward, the bayle had great authority over the lives of the slaves. At the time of registration, another official, the alcaldí del rey, together with the bayle or his deputy, interviewed the slaves, using translators if necessary, concerning their origin and the circumstances of their enslavement. The sellers had to swear that their slaves had been legally purchased or acquired as a result of good war or just war.43 Barcelona had similar laws to determine if slaves had been legally acquired.44

The bayle and his agents set a price for each slave. White slaves were the most expensive, and women were more expensive than men. Canarian slaves were cheaper than Muslims. Newly arrived black slaves were the cheapest of all, because they were assumed to need more training. Blacks who had lived previously in a Muslim or Christian kingdom were more highly valued, because they were assumed to be more fully acculturated than those who came directly from black Africa.45 Adults usually commanded higher prices than children or adolescents. Those who were judged to possess desirable qualities—beauty, intelligence, skills—carried higher prices. The bayle set each slave’s price and collected the royal duties. Then he gave the owner a receipt noting the slave’s name, condition, and place of capture. For slaves to be sold outside the kingdom, the receipt also listed name of the owner and where the slave was to be sold.46 The dealers regained custody of their slaves after the bayle had completed his work, though his staff would continue to monitor the lives of the slaves. The bayle’s agents visited towns of the kingdom to determine if the slaveholders had registered their slaves and paid the requisite tax on them. He was also responsible for the pursuit and apprehension of fugitive slaves and for the sale of criminal slaves who came to be owned by the Crown.47

The German traveler Hieronymus Münzer of Nuremberg visited Spain in 1494–1495 and commented on the Canarian slaves he saw in Valencia:

I saw in one house men, women, and children for sale. They were from Tenerife, an island of the Canaries group in the Atlantic Ocean, who, having rebelled against the king of Spain, were finally reduced to obedience. The people were being sold in the house, and at that time there was found a Valencian merchant who had brought 87 in a ship; 14 died on the trip, and he put the rest on sale. They are very dark, but not black, similar to the Turks; the women [are] well proportioned, with strong and long limbs, and all of them bestial in their customs, because until now they had lived without law and sunken in idolatry.48

In Andalusia in the early modern centuries, a similar process to that of Valencia was used to determine the origin of slaves and if they could be sold legally. Muslims, either captured in Christian raids on the coasts of North Africa or apprehended on the Spanish coast while trying to seize Christian captives, had to be registered with the public authorities, either the local captain general or the governor of the fortress, before they could be sold. They had to be declared to be slaves of “good war.” If they were, the royal impost of twenty percent could be paid and the slave then sold. Captives who came from North African regions whose rulers had signed peace treaties with the governors of the Spanish enclaves on the North African coast could not be enslaved. They were freed, and the Christians who had illegally captured them received punishment.49

In Granada, slaves were sold in the public markets or in private homes. Few slave merchants in Granada were foreign; most came from Granada or other parts of Andalusia. Merchants from Málaga traded mostly in North African slaves, whereas merchants from Seville specialized in sub-Saharan Africans.50 Sometimes slaves were sold along with other possessions. As an example, in 1536, the mayor of Marbella sold a small vessel, a fusta named “La Guzmana,” in Málaga and included the boat’s caretaker in the deal, a black slave named Francisco.51

Seville in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries was the nexus of a trade that brought enslaved people to Spain from Africa and the Canaries, acquired others via Portugal, and reexported many to other parts of the peninsula and further afield in Europe and to Spain’s overseas possessions. The human merchandise usually arrived overland from Portugal or by ships that passed up the Guadalquivir River from the Atlantic. Their owners sold them by auction or privately in portions of the city known for slave sales. The Calle de las Gradas near the cathedral was the most famous, followed by the Calle de Bayona and the Plaza of San Francisco. Slave dealers would parade their wares through the streets, accompanied by an auctioneer who would arrange sales on the spot, mostly to private buyers. Buyers acted for themselves or through an agent. Married women had to have their husband’s permission to buy or sell a slave, but widows could act for themselves or for their children. Once the sale took place, the parties went before a notary and recorded the transaction in a document that included details about the buyer, the seller, and the slave. Throughout the kingdom of Castile, the alcabala, or tax on sales in the markets, applied to slave sales. Slaves moving through Cádiz and in and out of Seville were subject to taxation, which their owners paid. A customs tax (almojarifazgo) in 1502 set the rates at 5 percent on entering slaves and 2.5 percent on those who left. If masters brought in slaves for their own use, they were exempt from paying the customs fees, unless they were bound for the Spanish colonies in the Americas.52

Citizens of Seville were the most numerous among the slave dealers, and other Castilians joined them, as did Basques from Vizcaya. It is interesting to note that merchants who dealt in slaves, even in as important a slave market as Seville, were not exclusively slave merchants. Rather, their slave dealings were only part of a wider range of commercial ventures. The trade carried a social stigma, as merchants who dealt in slaves were considered less than good Christians, even though they were Old Christians and not recent converts. Foreign merchants were there as well, as both sellers and buyers. The Portuguese were the main suppliers of African slaves, bringing them from the Portuguese enclaves on Africa’s west coast to Lisbon or to Portuguese ports in the Algarve such as Faro and then to Spain by way of land routes that hugged the Atlantic coast or through southern Portugal to Extremadura, where the town of Zafra was a major nexus. Some Portuguese merchants resided in Seville as agents of Lisbon slave merchants. As one indication of their importance, five Portuguese slave traders in Seville accounted for just over 40 percent of all the slaves sent to Spain’s American colonies in 1569–1579. The Portuguese were most often sellers, and some of them formed associations with locally resident Genoese and other Italian merchants to import slaves. Genoese merchants resident in Seville occasionally made trips themselves to the Portuguese enclaves in West Africa to bring back slaves to Seville. By the late fifteenth century, Flemish and English merchants came to Seville to purchase slaves.53

Throughout Iberia, as elsewhere in the Mediterranean world, the sale of a slave was an intricate dance between the buyer and the seller, who had to pledge that the slave was a product “of good war, not of peace, and that he or she was not a fugitive, nor consumptive, nor possessed by the devil, nor a drunk, nor a thief, nor blind in one eye or both, nor a bed wetter, nor suffering from epilepsy or buboes, nor from any other infirmities with all his or her good or bad qualities, seen or unseen,” as a formula from Seville stated.54 On the island of Mallorca, sellers of women slaves had to certify the state of their menstrual patterns and whether they were pregnant, though evidence for similar certifications is not available for Seville.55 Because it was difficult or impossible for the seller to demonstrate and for the buyer to determine all the conditions of the slaves, sometimes slaves were stripped naked to allow closer inspection, or the sales contract allowed for a trial period before the sale became final. If hidden defects became apparent, the purchaser could return the slave.56

A document of 1514 from Seville reveals how one such transaction played out. Gonzalo Días alleged that about two months previously Juan de Palma had sold him a slave woman from Guinea, black in skin color, and advertised as healthy. Días sold the woman a few days later to Cristóbal Rodríguez, who complained that the woman was ill with buboes and had a broken spine. Días asked that the original sale be nullified and that Palma take back the woman, mentioning nothing about the woman’s obvious suffering.57 Sometimes the sale documents indicated clearly the defects the slave suffered and offered money-back guarantees. One such was in 1523 in Seville, when a married couple offered to sell Antonia, a North African girl of six, to Luis de Celada. Antonia was described as marked on the chin and blind in one eye. Moreover, they attested that she had wet her bed several times while they owned her, a clear suggestion of psychological problems arising from separation from her family at such a young age. They agreed to let Celada return the girl for a full refund if he wished after two months.58

Donations

Not all slaves passed through public markets. After his conquest of Valencia in the early thirteenth century, the Aragonese king Jaume I distributed some two thousand slaves as gifts to rulers, nobles, and church officials throughout Western Europe.59 We can also find examples of slaves given as gifts by their proprietors. In 1301 the lord of the town of Borriol in Valencia gave his mother a white slave of Muslim origin named Cozeys.60 Slaves also appeared as part of dowries for young women of the elite groups.61 King Fernando and Queen Isabel made gifts of a number of captives enslaved following the conquest of Málaga in 1487, and in 1491 Fernando gave his aunt three slaves taken from a Muslim ship.62

Slave owners had the option of donating their slaves to the church. In this, as in so many other aspects of slaveholding, masters acted from a variety of motives, and the outcome could be positive or negative for the slave. Slaves who provided difficult to manage and whose reputations rendered them impossible to sell could be donated. Masters might want to make favorable provisions for their donated slaves. In the city of Murcia in 1772, a town councilor who had been cured at the Hospital of San Juan de Dios showed his gratitude for the cure by giving his slave Antonio Nicolás de la Santa Cruz to the hospital. He added a provision that seemed to show concern for the slave by making the donation conditional on the fact that the hospital would never sell the slave outside the area of Murcia. A diametrically opposed case occurred in 1763, when the Marquis of Corvera donated a slave with the proviso that he never be sold to anyone residing in Murcia or its jurisdiction.63

Price: Age and Gender

Several factors influenced the price that a slave would fetch on the market. These included age, gender, ethnicity, skin color, health, training and skills, religion, and degree of acculturation. Conviction for a crime lowered the price of a slave. We have little evidence for prices in Islamic Spain and little more than sketchy evidence for Christian Iberia. For those reasons, prices in this section appear in qualitative and comparative terms, not in absolute figures.64

In southern Spain in the late Middle Ages and early modern period, most sales took place when slaves were in their most productive years: in Granada between 11 and 40 years of age. For Seville, the most expensive slaves were women between 15 and 25, next came men between 12 and 22 to 25 years. Those below 11 and above 35 were cheaper still, and infants less than a year old and mature adults above 56 brought the lowest prices. In late sixteenth-century Huelva and in eighteenth-century Murcia, most sales of slaves, both men and women, took place when the slaves were between 16 and 30 years old.65 In late sixteenth-century Córdoba and Lucena, slaves in their twenties fetched the highest prices, followed by those between ten and nineteen and by those in their thirties. Slaves below ten and above fifty brought the lowest prices.66 A similar situation prevailed in the early seventeenth century on the island of Lanzarote, when 49 percent of the slaves were between sixteen and thirty when they were sold.67 We see the same in Cádiz in the eighteenth century, when slaves of both sexes brought the highest prices when they were twelve to twenty-five.68

Buyers in most cases sought to buy women more eagerly than men. In late sixteenth-century Salamanca, Córdoba, Jaén, and Lucena, women brought higher prices than men in all age groups.69 The same was true in early modern Ayamonte and on the island of Lanzarote in the early seventeenth century.70 The same pattern emerged from the records of Cádiz in the eighteenth century, where women commanded higher prices than men.71 In Alicante in the late Middle Ages, by contrast, men fetched more than women as slaves. White slaves, usually of Islamic origin, commanded the highest prices, followed by Canarians, and then last by blacks.72

Questions of “Race”

Scholars have only recently begun to wrestle with the problems of race and racial perceptions among medieval and early modern Muslims and Christians.73 This effort is complicated, as modern Western concepts and misconceptions of race are anachronistic when applied to earlier periods. Certainly people in earlier periods recognized differences of skin color as well as cultural distinctions and categorized slaves accordingly. Religion and language, though, tended to be more important categories. We can see some indication of the value placed on slaves of different origins in both contemporary comments about them and the prices various groups commanded in the market.

Muslim slave owners had stereotypical views of slaves of different origins. Muḥammad al-Saqaṭī, a market inspector in Málaga in the late twelfth century and early thirteenth, commented on slave women, revealing his views on ethnicity, class, and gender. He wrote that Berber women were best to exhibit voluptuousness, Roman (i.e., European) women were best for care of money and the larder, Turkish women for producing valiant sons, Ethiopians for serving as wet-nurses, Meccans for singing, Medinans for elegance, and Iraqis for coquetry. He may have been echoing a slave dealer who proposed a course of upbringing to produce the ideal slave woman. One first should import a nine-year old Berber girl of good origin. She should then spend three years in Medina and another three in Mecca. After that she should be educated in Iraq and finally sold at twenty-five. Thus, for he suggested, her good origin would be united with virtues and skills acquired along the way, thus allowing her to be valued more than girls with beautiful eyes.74

Slaves from many origins ended up in the Christian kingdoms of Iberia. In fifteenth-century Christian Mallorca, there were slaves from a variety of origins. Most of them were Muslims, either North Africans or the descendants of Muslims who lived on the island at the time of its conquest. There were also others: Christian prisoners of war such as Sards and Genoese, Canarians, Greeks, people from the Balkans, Armenians, Tatars, Russians, Circassians, Turks, and people from sub-Saharan Africa.75

In Seville in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, most slaves were of North African or sub-Saharan African origin. Others were more exotic and certainly fewer in numbers. There were some few American Indians, most of them from the Caribbean islands. One of these, named Juan, had been captured as a child in one of the first Spanish raids on the interior tribes of the island of Española, in this case the Higuey. A very small number of slaves from the Indian subcontinent reached Europe, brought by the Portuguese and then sold in Spain. Some Canarian slaves reached Seville, as we saw earlier. Despite the express order by Fernando and Isabel outlawing the trade, it took royal action, protests by church officials, and the work of lawyers hired by free Canarians to free the last of the Canarian slaves.76

Geographical origins often determined prices for slaves. For Seville, the most expensive slaves were those of North African origin. Franco Silva suggested that this was due to “their exceptional physical resistance.”77 That, in turn, could well be due to the fact that they had lived their lives in a region environmentally similar to that of southern Spain and shared in the common disease pool of the western Mediterranean, making them less prone to contract unaccustomed diseases. Black Africans and Canary Islanders fetched the next highest prices, and in both cases women were worth more than men, as they were destined to domestic service. American Indian slaves were the cheapest, for they often suffered and died from Old World diseases, and because they were subject to restrictions on their sale.78

Andalusians and other Iberians in the fifteenth century and later tended to view people of sub-Saharan ancestry in complicated ways. On the one hand, they tended to lump all of them together as negros, or blacks, regardless of whether they had come directly from West Africa or had been born in North Africa or Iberia or the Atlantic islands. A cultural division led the Iberians to designate as ladinos those Africans who had acquired the ability to speak one of the peninsula’s Romance languages and as bozales those who had not. The term ladino apparently derived ultimately from latino, a term for a person of Iberian origin who had learned Latin following the Roman conquest. These terms, however, could also apply to any slave from North Africa, black or not—an imprecise conflation of culture and physical appearance. Those of mixed racial origins, in most cases the offspring of a white father and a black woman, usually a slave, were called mulatos or de color de membrillo cocho (the color of cooked quince). The biological mixing that took place over generations complicated the clear designation of a person’s ethnicity and caused convoluted attempts at precise definitions: “white tending to brown,” “slightly mulatto,” or “he is a mulatto and his father is a black.”79 As hard as the buyers and sellers and public officials tried for precision, it sometimes escaped them, as in the case of Beatriz, girl of twelve years, described at the time of her sale in Córdoba in 1522 as being as white as a mulatta and of Gypsy lineage.80

In the first two-thirds of the sixteenth century, buyers in Jaén preferred sub-Saharan Africans, supplied by the Portuguese from their contacts with West Africa. White slaves, called berberiscos or people from Barbary, were mostly Muslims from North Africa. Owners in Jaén seem to have considered that they were less docile than the blacks and that they were far more likely to flee, because they had greater hopes of reaching their homeland. The aftermath of the revolt of the Moriscos, late in the sixteenth century, brought Granadan Moriscos to the market, as we saw earlier. In the seventeenth century, availability in Jaén changed again, this time to North Africans, especially after the revolt of Portugal in 1640 and its independence in 1668 constricted the trade from sub-Saharan Africa to Europe.81

White slaves, usually of Islamic origin, commanded the highest prices in Alicante in the late Middle Ages, followed by Canarians, and then last by blacks.82 Black women commanded lower prices than North African women as slaves in early sixteenth-century Málaga.83 The same was true in late-medieval Barcelona, perhaps because the purchasers of potential concubines preferred white slaves.84 Sixteenth-century Granadans categorized North African slaves by skin color. Their percentages in the sale documents are as follows:85

white 48%

black 24%

unspecified 17%

mulatto 1%

membrillo 3% (quince)

loro 8% (olive)

For Málaga in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, an elaborate vocabulary existed, reflecting the ethnic diversity and generations of biological mixing.86

blanco (white)

negro (black)

moreno (dark)

moreno claro (somewhat dark)

membrillo (quince)

membrillo cocho (cooked quince)

membrillo cocho claro (light cooked quince)

membrillo cocho oscuro (dark cooked quince)

trigueño (wheat)

trigueño claro (light wheat)

trigueño oscuro (dark wheat)

rubio (blond)

rosa (pink or rosy)

pelinegro (with a black skin or with black hair)

buen color (good color)

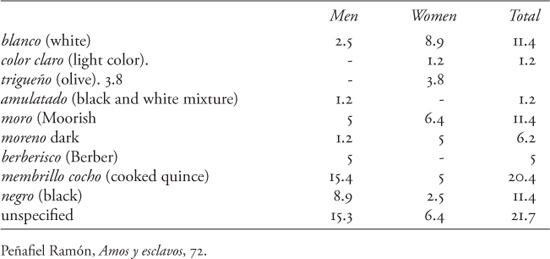

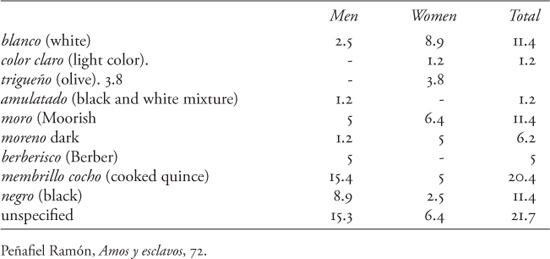

For Murcia in the early eighteenth century, one modern historian provided the percentages shown in Table 1 (see next page) for the perceived skin color, ethnicity, or geographical origin of the slaves sold in the market.87

Marked Slaves

Sale records and other documents in early modern Spain carefully described the slaves involved. These descriptions included the marks slaves might bear on their faces or bodies. Among these were the scars from wounds and smallpox or chicken pox.88 The documents also recorded hierros—marks of the iron or brand marks. Modern commentators have mostly followed the documents and have not examined carefully the descriptions of the marks. It turns out that not all the marks were the product of hot iron burning the flesh, despite the common use of hierro. Aurelia Martín Casares has identified three distinct types. North African women often bore tattoos applied in their homelands to indicate tribal affiliation or to enhance beauty. The tattoos were on the forehead, between the eyebrows, or on the chin. They also appeared occasionally on other parts of the body. Spanish documents referred to them incorrectly as hierros a la berberisca, or North African brand marks. Sub-Saharan Africans often reached Iberia with cicatrices, scars left from shallow incisions, usually on the cheeks. They had acquired these marks in their natal societies as indications of the group to which they belonged. The fifteenth-century Italian traveler Alvise da Mosto reported on Senegambian women “who delight to work designs upon their flesh with the point of a needle, either on their breasts, arms, or necks. They appear like those designs of silk that are often made on handkerchiefs: they are made with fire, so that they never disappear.”89 Such bodily decorations were distinct from the true brand marks inflicted on some slaves in Iberia.90

Table 1. Perceived Skin Color, Ethnicity, or Geographical Origin of Slaves Sold in the Market, Murcia, Early Eighteenth Century

Slave owners and public officials certainly branded some slaves, but it appears that it was usually unsuccessful fugitives who suffered the branding. Such marks obviously would diminish the value of the slave, and masters would have kept that in mind.91 A common marking for fugitives was a mark of an “s” on one cheek and an “i” on the other, signifying the Latin slogan sine iure, or outside the law. Often the marks were popularly interpreted to mean “s” and a straight-line symbol of a nail (clavo in Spanish), so that when combined they read as esclavo, Spanish for slave.92 Many modern scholars have followed the popular interpretation. Other brand marks included whole words indicating ownership.

Descriptions of slaves with marks appear in notarial documents from late seventeenth-century Jaén. From a sale document: “my own slave María Agustina of twenty years of age, branded (herrada) on the forehead, chin, and nose in the style of North Africa (Ververia).” From another sale document: “a slave that I have named Teresa, white in color from North Africa, without iron or mark, and about twenty-six years old.” From a power of attorney: “a slave named Juan Antonio, of about twenty-four years of age, with a good body, branded on the forehead and on both sides of the nose and with other brand marks on the cheeks. . . . He has been a fugitive.” From a sale document: “a dark black slave named Manuel, nineteen years old, with a good body, and no marks or brands.” From a sale document: “a dark black slave, with freckles, named Catalina, of about twenty years of age, with a mark on her right side.”93 For Huelva in the late sixteenth century, only two slaves with brand marks have left traces in the documents. They were both former fugitives and described as “almost white” and perhaps hard to distinguish from members of the free population.94 Slaves with brand marks were still sold in eighteenth-century Murcia.95

Fraud

Sellers often tried to pass off slaves as healthier or younger than they were. Buyers examined their prospective purchases carefully and insisted that the sales contracts specify that they could return the slaves for their money back if they discovered defects within a short period.

Muḥammad al-Saqaṭī, the market inspector we mentioned earlier in this chapter, reported on examples of fraud in slave sales in the treatise that he wrote on the management of the market. Slave merchants attempted to make their human merchandise more attractive with practices that varied from applications of cosmetics to more elaborate ruses. In his treatise, al-Saqaṭī included recipes that slave-dealers used to improve the chances for sales at high prices. These included coating the face and limbs of black slaves with violet oil and perfume. Hair could be darkened by using oil of myrtle and oil of fresh walnuts followed by a special wash. Tattoos could be lightened by a paste whose ingredients included rose roots, bitter almonds, and melon seeds kneaded into honey. Pock marks could be obscured and signs of leprosy hidden. Virginity could be restored, at least apparently. “For those women who have been deflowered, they use the core of bitter pomegranates and of gall nuts molded with cow bile which is applied to them and they become as they had been.”96 Al-Saqaṭī also related the account of a free Muslim woman who conspired with a slave dealer to pass her off as a Christian captive from northern Spain. The dealer found a buyer, and after the sale the woman revealed herself to be a free Muslim. She threatened to denounce the buyer, who could have faced stiff penalties for holding a Muslim slave, and forced him to take her to Almería and to sell her in still another ruse, perhaps sharing the profits between them.97

Similar fraudulent practices appeared on the Christian side as well. In the Crown of Aragon, the kidnapping of local free people, both Christian and Muslim and often children, and illegal raids on foreign Muslims caused concern to the royal officials. They insisted that sale and import documents include an albaranum, a guarantee that the slaves were not free victims of kidnapping and that dealers had paid the customs dues on imported slaves captured in legal raids.98 The sale of free people could occur when heirs failed to acknowledge manumission by a slave owner’s testament. In such cases, courts could declare the slave to be free. In 1508, for example, María, a black freed slave of 14 years of age, found herself sold by an official of Seville’s cathedral, a colleague of her former master. She declared herself to be free, instituted a suit, and obtained confirmation of her freedom.99

Some of the slaves traded in Iberia were re-exported from the peninsula. Before 1500, most went to Italy, for there was a lively trade between the ports of Iberia and those of Italy. After 1500 most went to the Atlantic islands or to the Indies. Despite the re-export trade, the majority remained in Iberia and were put to work, as we will see in the next chapters as we examine their lives and the tasks to which they were assigned.