April 6, 1993 began as a normal Tuesday in the sports department at the Milwaukee Journal. Well, maybe it was a little busier than normal because North Carolina had beaten Michigan’s Fab Five in the NCAA Championship Game the previous evening at the Superdome in New Orleans. The Milwaukee Brewers were playing—and losing—their season opener against the Angels in Anaheim.

And then a reporter called the office to say that the Packers had signed free-agent defensive end Reggie White to a four-year, $17 million contract. The announcement, which came three months after a collective bargaining agreement brought free agency to the NFL, capped a long courtship battle that left the Washington Redskins, San Francisco 49ers, and Cleveland Browns at the altar and stunned the football world, the sports world, and—perhaps most of all—Packers Nation.

This predated the Internet. There were no cell phones to ping with updates. When people heard about a big, breaking news story from a family member, friend, or co-worker, they would seek out a television or a radio for details and confirmation. Or they would call the sports desk of the local paper. The phones began ringing in the sports office nonstop to the point where answering it became a mantra: “Journal Sports, the Packers have signed Reggie White. How may I direct your call?”

With a $6 million bonus and a $9 million payout the first year, White, 31, became the highest paid player in Packers history at the time and almost single-handedly erased the notion that sending players to Green Bay was like sending them to Siberia, a stigma that had haunted the franchise in the post-Lombardi era. If the best player in the league—who happened to be black—chose Green Bay, other free agents could as well. But it seemed like such a long shot. During a five-week tour, White was being wined and dined by virtually every big-market team in the league. He was greeted by limousines, marching bands, and parades.

White and his agent, Jimmy Sexton, were in Detroit, visiting the Lions, when general manager Ron Wolf delivered another in a series of exploratory phone calls. As a courtesy White decided to visit Wisconsin. With a media contingent staking out the airport, White and Sexton arrived in town on a private plane at a small auxiliary terminal. Jerry Parins, the Packers’ director of security, picked up the duo in a Jeep Wrangler. Wolf took them onto the playing surface at Lambeau Field, and they went to eat at a Red Lobster near the stadium. The low-key approach grabbed White’s attention. Legend has it that after White told the Packers “God will tell me where to play,” coach Mike Holmgren left White a message saying, “Reggie, this is God. I want you to go to Green Bay.”

After days of intense prayer and contemplation, White returned to Green Bay for his introductory press conference. “I was up and down,” White said. “I thought I had a decision made. I changed and I changed it again. I had to have some peace of mind. That’s what I was looking for. I think every team is shocked, but I made the decision.”

That decision changed the landscape of Green Bay like few others in franchise history. “It’s hard to quantify what Reggie meant to the Packers,” said Bob Harlan, who was team president at the time of the acquisition. “So many things changed when he entered the picture.”

The change on the field was immediate. In each of his eight seasons with the Philadelphia Eagles, White recorded double-digit sack totals. He went to seven Pro Bowls and earned six All-Pro nominations and the 1987 Defensive Player of the Year award. At 6’5” and 291 pounds, he was virtually impossible to block one-on-one. But he also wreaked havoc on double teams. In his first year with the Packers, he recorded 13 sacks and 79 tackles. Packers defensive coordinator Fritz Shurmur built his gameplan around White and watched everyone else on the defense—and in the locker room—improve both physically and mentally by association. “I hate losing,” White said. “Losing ties my stomach in a knot. It follows you around and destroys your sleep. It torments you. And I let guys know, ‘If losing does not torment you, move on. Go play for somebody else.’”

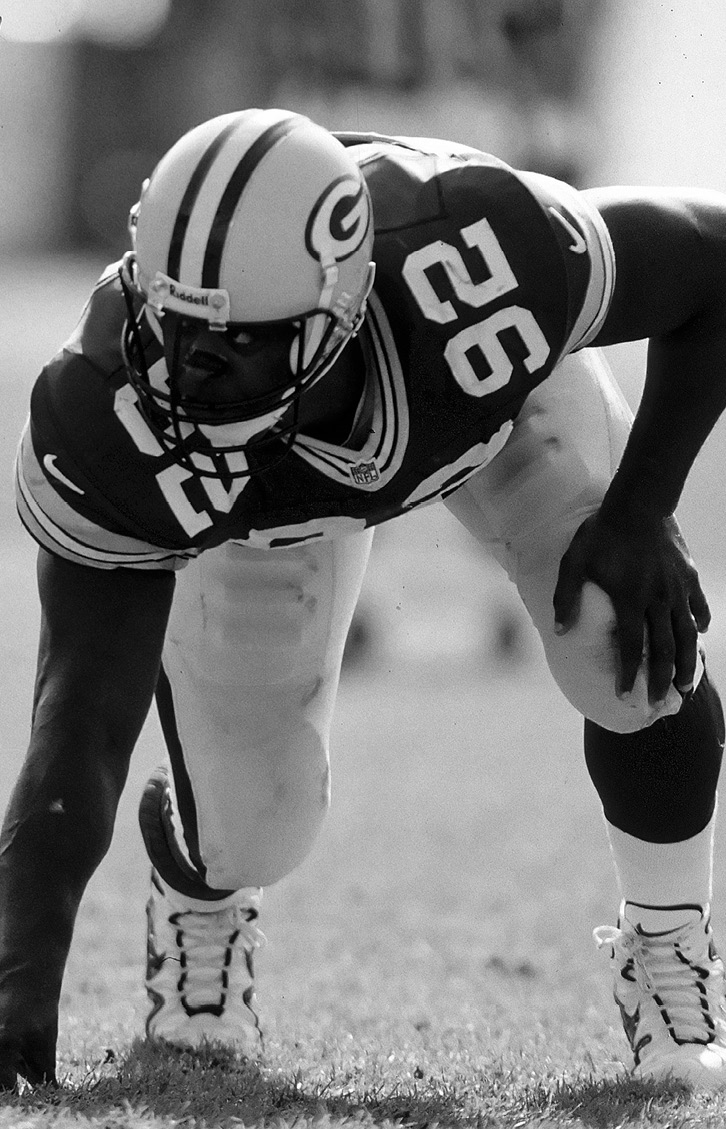

Reggie White lines up in a three-point stance in 1997, a year in which he had 11 sacks and helped lead the Packers to the Super Bowl.

White helped recruit players like Sean Jones, Jamie Dukes, and Keith Jackson. He sold them on the idea that Green Bay was a place to focus on football and bask in the undying support of fans. Jones, who had played in Los Angeles and Houston, liked what he found in Green Bay. “The thing that people have to know is that just because there’s a lot of white people, that doesn’t make them racist,” he told Sports Illustrated. “It’s probably the least racist place I’ve ever been in my life. That said, they don’t know what they don’t know. They don’t know how to cut a fade with a No. 2 and they don’t know how to make fried chicken and cornbread. Where’s the black history museum? Where’s Chinatown? They didn’t have any of that, but they embraced you and they wanted to win.”

Jackson, who had played with White in Philadelphia, agreed. “Before that decision guys would say, ‘If Green Bay drafts me, I don’t want to go.’ It was Siberia,” he said. “But Reggie White saw something different about it…Reggie saw all these positives about Green Bay that nobody really knew about. He saw it as an opportunity to go somewhere where the people are super fans. And when you lose a game, there’s nobody screaming at you, saying you’re a bum. The media is reporting the facts and not trying to create a controversy. It was actually an oasis to play football, and you really concentrated on being a football player.”

In order to help White and his recruits acclimate to Green Bay—a city with a 95 percent Caucasian population—Wolf arranged for regular visits with a Milwaukee barber and had Wednesday meals catered by Bungalow Restaurant, a Milwaukee eatery that specialized in catfish, barbecue, and other Southern staples. “Reggie helped change the culture up there a lot,” Holmgren said.

White was deeply religious, hosting bible study sessions, quoting scripture, and mentoring young players. “Everything in the locker room revolved around Reggie,” wide receiver Antonio Freeman said. “If he wasn’t happy with the way you were acting, he let you know it. You didn’t want to hear that booming voice directed at you.”

Opponents didn’t want to see White bearing down on their quarterback. White recorded eight sacks in 1994, and the Packers’ defense vaulted from 23rd in the league to No. 2. White got 12 sacks in 1995, an effort that resulted in another Defensive Player of the Year trophy. In the championship season of 1996, he had 8.5 sacks and rag-dolled New England Patriots quarterback Drew Bledsoe three times in the Super Bowl to help clinch the Lombardi Trophy. The image of White jogging around the Superdome with the trophy aloft is iconic in Packers history, and people still wear his jersey to games at Lambeau Field.

There were, however, a few bumps in the road during his tenure. In January of 1996, White’s Tennessee church, Inner City Church of Knoxville, burned down. Packers fans held fund-raisers and came up with $250,000 for a reconstruction that never occurred. Then White gave a speech to the Wisconsin legislature that included some controversial remarks about race relations and homosexuality. There was some blowback, but nothing close to what happens in the social media age. It did, however, likely cost White a career as a TV analyst after his retirement.

White actually retired from the Packers on two occasions. He did it after the 1997 season but changed his mind two days later. Then he did it again after the ’98 season, which ended with him collecting 16 sacks and Defensive Player of the Year honors. “I just thank God for the opportunity to have played in front of these people for six years and to have been a part in bringing them a championship,” White said upon his retirement from the Packers after the 1998 season. “It’s an extreme honor to have played for the Green Bay Packers and to have played in front of the Green Bay Packers fans.”

White returned to action in 2000, spending a season with the Carolina Panthers. On December 26, 2004, White was at home in Cornelius, North Carolina, when he suffered a fatal cardiac arrhythmia, which was attributed to sarcoidosis, a tissue inflammation disorder, and the sleep apnea that had plagued him. He was 43 years old. “I cried for two hours,” former Packers safety LeRoy Butler said.