One afternoon several years ago, Ron Wolf and Bill Parcells were having lunch. The two age-old friends—both Pro Football Hall of Famers and Florida snowbirds—had watched the NFL’s annual awards show the previous evening and seen that year’s eight-person Pro Football Hall of Fame class unveiled during the 2016 NFL Honors. Although the player, who more than anyone else, had helped Wolf earn his own gold jacket—quarterback Brett Favre—was among the eight inductees, Wolf and Parcells also noted that two safeties—John Lynch and Steve Atwater—had been among the 15 finalists but weren’t among the five modern-era selections.

Wolf watched safety LeRoy Butler go to four Pro Bowls after inheriting him from the previous regime when he took over as the Packers’ general manager in November 1991, and Parcells coached Atwater during the 1999 season when the longtime Denver Broncos safety finished off his NFL career with the New York Jets, and they found themselves discussing why so few players at the safety position have been called to the Hall of Fame.

Wolf believes his Packers teams had three Hall of Fame players: Favre, defensive end Reggie White, who was inducted posthumously in 2006, and Butler, who in 2018 made the cut to 25 semifinalists but was eliminated from consideration shy of the list of 15 finalists whose resumes would be debated by the selection committee on the eve of the Super Bowl. “LeRoy deserves to be in that conversation,” Wolf said several days after his lunch with Parcells. “He was the quintessential safety. He could do everything you needed a safety to do: he could play at the line of scrimmage, he could tackle, he could cover man-to-man, he could dog [blitz]. He had no weakness. But he’s going to have a tough battle. A very tough battle.”

That’s because the safety position has long been overlooked, so much so that Lynch and Atwater’s inclusion in the discussion constituted significant progress. “This committee doesn’t elect safeties,” said longtime columnist for The Dallas Morning News, Rick Gosselin, who has been on the Hall of Fame selection committee for more than two decades. “We haven’t found a safety who’s played in the last three-and-a-half decades that we’ve deemed worthy of Canton. It’s the most overlooked position in the NFL in the Hall of Fame. That’s what Butler’s up against.”

Before Seattle Seahawks safety Kenny Easley, a seniors committee nominee, was enshrined in 2017, Philadelphia Eagles safety Brian Dawkins was inducted in 2018, and Baltimore Ravens safety Ed Reed was voted in during 2019, only seven true safeties were in the Hall of Fame, and the last one to have played an NFL game had been Ken Houston, who last took the field in 1980 and was enshrined in 1986. (Easley’s final season was 1987; Dawkins’ was in 2011.) The last true safety elected before Easley and Dawkins had been Minnesota Vikings safety Paul Krause, who retired in 1979 and wasn’t enshrined until 1998.

Many of the inductees who did play safety during their careers, including Ronnie Lott, Rod Woodson, and Aeneas Williams, were Pro Bowl cornerbacks before moving to safety later in their careers. Butler, who retired in 2001, was a first-team NFL all-decade selection for the 1990s along with Atwater. (Carnell Lake and Lott, a first-team, all-1980s pick, were the 1990s’ second-team safeties.) “When you start stacking the ones that belong, there’s just a lot of bodies in the queue right now,” Gosselin said. “I feel strongly it’s a position we need to move along. We’ve got to crack the door for these guys. Butler’s in very good company. For not being in the Hall of Fame, he’s with some great players. The Hall hasn’t recognized those players yet. And they need to.”

In Wolf’s opinion the two safeties most deserving are Butler, who finished his career with 38 interceptions, 20.5 sacks, and one Super Bowl title, and Darren Woodson, a five-time Pro Bowler who won three titles with the Dallas Cowboys. “Both of them really and truly are Hall of Fame material,” Wolf said.

Wolf said Parcells agreed during their conversation because Butler and Woodson were more complete players than Atwater and Lynch were. Butler’s candidacy—or lack thereof—became a topic of discussion in the wake of Favre’s election. Butler himself said he wasn’t fixated on it, but after Vince Lombardi era guard Jerry Kramer, another long-suffering Hall of Fame candidate and Packers fan favorite was finally enshrined in 2018, Butler basically took up Kramer’s title as the greatest Packers player not to be in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

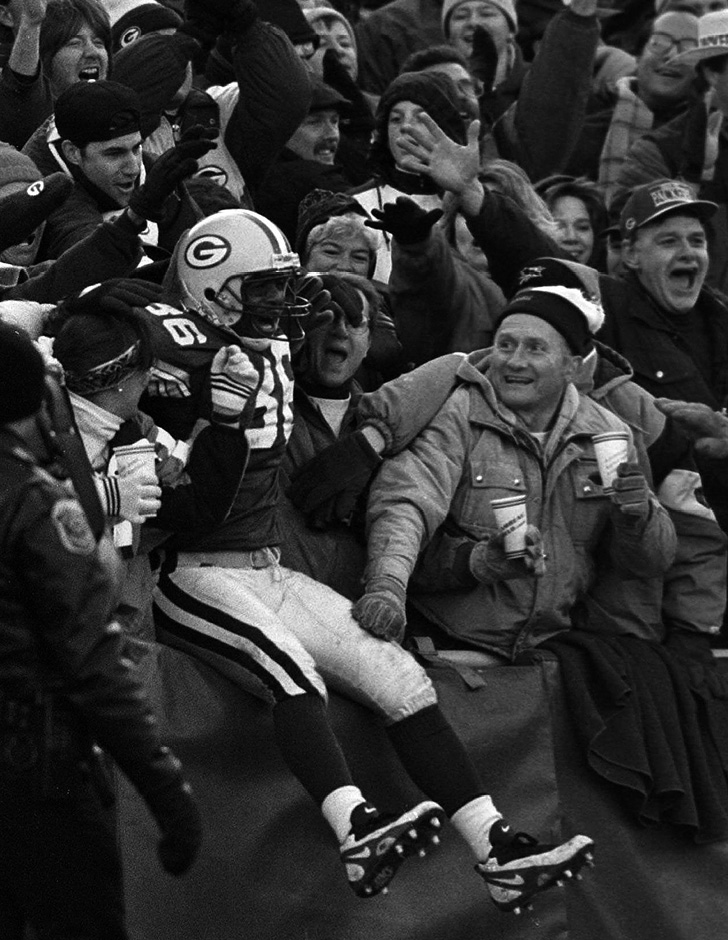

Safety LeRoy Butler, who invented the Lambeau Leap, celebrates with the Packers faithful after an interception in 1995.

A second-round pick from Florida State in 1990, Butler played his first two seasons at cornerback before Wolf hired head coach Mike Holmgren in 1992. Holmgren’s defensive coordinator, Ray Rhodes, decided to move Butler to safety, where he’d spend the next 10 years. Although Butler moved in part to make room for rookie cornerback Terrell Buckley, Rhodes also liked the idea of using Butler’s diverse skill set at safety. “It comes down to this: when I got the phone call to move to safety in 1992, safeties weren’t doing the things they’re doing now,” Butler said. “Ray Rhodes had this vision. Go back to before 1992 and see how teams were playing safeties and how I played—close to the line, making sacks, covering tight ends and third receivers. Troy Polamalu, Brian Dawkins—the recipe for how those guys played was the one we put out there in the 1990s.”

After Kramer was selected, he and Butler met up on the event circuit and got to talking. Kramer explained to Butler how he had made his peace in recent years with not being in Canton, and the two talked about their feelings for the Hall of Fame. “In my mind I know I made a difference and I know what these safeties now, the ones that weigh between 205 and 215 pounds, I know they’re playing that way because of me,” said Butler, who entered the Packers Hall of Fame in 2007. “If it didn’t happen, I’m fine with it. But it’d be fantastic if it did.”

Butler’s case would have been strengthened had his career not been cut short by injury. In going from being wheelchair-bound and struggling to walk with leg braces as a child to a cocky young cornerback from Florida State and then from inventing the Lambeau Leap to one of the greatest players to ever wear the green and gold, it seemed as though there was nothing Butler couldn’t do.

But in the end, he couldn’t heal the fractured left shoulder blade he suffered late in the 2001 season, leading to his retirement in July 2002, one day shy of his 34th birthday. Butler, who had started 116 straight games before the injury, wound up two interceptions short of becoming the first player in NFL history to record 40 or more interceptions and 20 or more sacks in his career. “We don’t win nearly as many football games as we did or have the kind of success we did without LeRoy Butler,” Favre said.

But perhaps Butler’s head coach at the time of his retirement, Mike Sherman, said it best. “As far as loving the game, loving his teammates, loving the Packers and loving the fans,” Sherman said, “he’s in a class all by himself.”