In the waning week of January 2019, a dreaded polar vortex hit the upper Midwest and plunged temperatures in Wisconsin below zero. On January 29 the deep freeze dropped temperatures in Green Bay to -13. Two days later it was -26. Many businesses closed; some opened later than normal. Schools and malls were empty. The United States Postal Service postponed deliveries for two days, citing concern for the safety and well-being of its employees. Playing to a captive audience, television newscasters urged people to stay home and indoors unless heading outside was absolutely necessary. Through it all, nobody played football. But more than 50 years earlier the Packers did in similar conditions.

It’s virtually impossible to be a Packers fan—or a Wisconsin resident—and not know what happened on New Year’s Eve 1967, when Green Bay, seeking its third straight NFL title, squared off against the Dallas Cowboys at Lambeau Field. The temperature at kickoff was -13, and wind chills ran to -50. With an announced crowd of 50,861 looking on, the Packers rallied from a late deficit, won the game 21–17, and clinched a trip to the second Super Bowl on Bart Starr’s quarterback sneak with 13 seconds left. “To this day, it’s the game everyone identifies with this team,” said Packers historian Cliff Christl, who attended the Ice Bowl as a 20-year-old sitting in his family’s season seats in Section 18, Row 13. “With the cold weather, the drama, the championship—it was the signature game in Packers history, Bart Starr’s history, Vince Lombardi’s history. It was the culmination of the era and it is one of the great games in the history of the NFL.”

As with much of Packers history, facts about the game are somewhat hazy. Almost everybody in Wisconsin has a friend or relative who claims to have attended the game, but many people who claim to have been shivering in the bleachers actually gave their tickets away. The CBS announcing crew that day—Ray Scott, Jack Buck, Frank Gifford, Pat Summerall, and Tom Brookshier—knew it was going to be a competitive game. The Packers had beaten Dallas in the previous year’s thrilling championship game en route to a victory against the Kansas City Chiefs in the first Super Bowl.

The coaching matchup—Green Bay’s Lombardi and Dallas’ Tom Landry—provided a study in contrasts. Lombardi was emotional and regarded as an offensive innovator; Landry, who had worked as an assistant on the New York Giants’ staff with Lombardi in the mid-1950s, was stoic, subdued, and known for his “Doomsday Defense.”

The Packers had future Hall of Famers on their roster, but Paul Hornung and Jim Taylor were gone, a few key players like Jim Grabowski and Elijah Pitts were hurt, and the clock was winding down on the dynasty. An eight-year-old outfit that later went on to call themselves “America’s Team,” the Cowboys had up-and-coming stars and were anxiously seeking a signature victory to establish their own championship tradition. They were 9–5 in the regular season but overwhelmed the Cleveland Browns 52–17 in the Eastern Conference title game.

Nobody is certain exactly when the term Ice Bowl originated. Christl said the first reference he came across was in a story by William Gildea, a columnist for The Washington Post, but it was used to describe the conditions in the Packers’ previous playoff game—a victory against the Los Angeles Rams on December 23 at Milwaukee County Stadium. Temperatures in that game featured a windchill of 4 degrees, which seemed cold at the time but was balmy by Ice Bowl standards. “The interesting thing about that game is that the Rams were the team that the Packers were most worried about,” Christl said. “They were 11–1–2 that season and they had great players. The Packers were underdogs against the Rams the week before the Ice Bowl.”

The Packers beat the Rams 28–7 to win the Western Conference title and set up the Ice Bowl, a phrase that was inserted into a Chicago Tribune headline on New Year’s Day and became the subject of sports lore.

Shortly after the game began at 1:10 pm, referee Norm Schachter and his officiating crew abandoned their whistles because the metal was freezing to their lips. They relied on voices and hand signals to control the game. The following year officials began using plastic whistles.

According to fans who attended the game, the only place spectators could buy a beer in Lambeau Field was in the men’s room. Vendors moved cases to the men’s room because it was too cold to open bottles in the seating bowl, and as one fan said, “the bathroom was the only place you could take a drink without having the bottle freeze to your lips.”

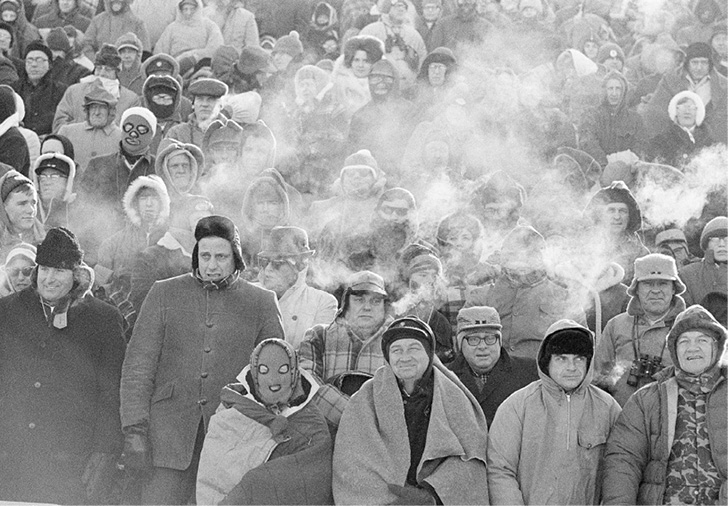

Despite -13 temperatures at kickoff, devoted fans watch the Packers defeat the Dallas Cowboys 21–17 in the Ice Bowl.

One of the early casualties of the Ice Bowl was the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse band performance, which was scrapped due to the cold. The 173-member band, which had rehearsed in cold weather for weeks in anticipation of performing in front of a TV audience of nearly 100 million, hit the field in order for CBS crews to figure out camera angles for the broadcast. The band attempted to rehearse in -13 degree temperatures, but mouths froze to instruments, fingers froze in position, players passed out, and some were taken to St. Mary’s Hospital.

At some point in the mid-1960s, Lombardi had contacted Henry Beemster, owner of Beemster Electric in Green Bay, to ask about a system to keep the field playable in cold, snowy conditions. The “electric blanket” system was installed in the summer of 1967 with help from a local architectural firm and General Electric, which helped bury 14 miles of cable six inches below the playing surface. The cost was reportedly $80,000, and Lombardi was proud of the innovation. “It was his pride and joy,” recalled Bud Lea, columnist for the Milwaukee Sentinel. “He loved showing the thing off. He was like a kid with a toy, playing with all the knobs on that thing.”

The day before the game, Lombardi showed the blanket to Dallas reporters. Cowboys radio announcer Bill Mercer planned to have the stadium engineer on his pregame show to discuss the system. The temperature was in the 20s with little wind. Nobody expected the cold front to move in as quickly as it did. In two games prior to the Ice Bowl, the blanket was used with temperatures in the low-to-mid-30s and worked splendidly. On New Year’s Eve, the 40-man ground crew removed the blanket a couple hours before kickoff and swept the field with brooms. Disaster ensued. Condensation caused a moisture build up on the field surface, and it began to freeze as the game drew near. “It was like a skating rink,” Packers guard Jerry Kramer said.

Lombardi was livid about the malfunction. He first blamed press agent, Chuck Lane, and then the tarp. “We just have to use a different tarp,” he said at a press conference before Super Bowl II. “Moisture forms between the tarp and the turf and freezes. That is what caused the field problems we had for the championship game. It was soft a little beneath the turf, but there was a hard crust on the surface.”

The game on the hard surface wasn’t a particularly artistic display of football. The Packers jumped to a 14–0 lead and—given their familiarity with the cold weather—it seemed they were headed to an easy victory in a battle of wills. The Cowboys parlayed a pair of Packers fumbles into a touchdown and a field goal. An unexpected option pass put them ahead 17–14 with four minutes, 50 seconds left. Led by future Hall of Fame quarterback Starr, the Packers marched down the field. “It was probably the greatest drive I’ve ever seen,” Lea said. “To do that under those conditions was incredible. There were no mistakes, no fumbles.”

But two plays before Starr’s winning plunge, Donny Anderson was stopped just shy of the goal line. Many of his teammates and several Dallas players thought Anderson had scored. On the next play, Anderson slipped on the ice and didn’t come close to pay dirt. With 16 seconds left, Starr called timeout. Having seen his running backs slip on the tundra, he suggested to Lombardi that he would run a sneak, a play that wasn’t even in the playbook. “I can shuffle my feet and lunge in,” the quarterback told the coach.

“Well, then run it, and let’s get the hell out of here,” Lombardi replied.

It was a gutsy call—Brown Right, 31 Wedge—and it was designed to go to fullback Chuck Mercein. Starr didn’t tell his teammates of his plan to keep the ball. With no timeouts left, an unsuccessful attempt would have ended the game, but Kramer had noticed that Cowboys defensive lineman Jethro Pugh tended to stand up straight in goal-line situations. With help from center Ken Bowman, Kramer pushed Pugh aside to clear room for Starr.

Mercein accounted for 34 of the 68 yards on the Packers’ final touchdown drive. He carried the ball twice for 15 yards, caught a 19-yard pass, and then bucked his way for eight yards down to the 3-yard line. Without his contributions and early catches by Boyd Dowler, the Packers might not have won.

* * *

Cowboys defensive lineman Bob Lilly claims to have seen three young, shirtless fans in the stands when he headed onto the field for pregame warmups. Lilly stuck to his story for decades, but nobody has corroborated the claim. Shirtless fans and cold weather didn’t seem to become a thing in sports until much later. A popular rumor states that an elderly fan died of exposure as a result of attending the Ice Bowl. There are, however, no records in Milwaukee or Green Bay newspapers that confirm such an event.

But in addition to the usual bumps and bruises inherent in high-level football, many of the players experienced weather-related injuries, including frostbite and lung problems. Coaches from both teams were reluctant to let players wear gloves, though several Packers players defied Lombardi by doing so. “I had some brown gloves, so nobody would know,” Packers linebacker Dave Robinson said. Gloves weren’t enough to prevent frostbite, though, for which several Packers players were treated. Had the game gone into overtime, the problems would have mounted.

Sandra Clark, the wife of Cowboys defensive lineman Willie Townes, told The Dallas Morning News her husband was stricken at the game and was never the same afterward. “He came home from the Ice Bowl, and his hands were still frozen,” she said after Townes’ death. “Then the skin began peeling off. They hurt him for the rest of his life.”

Lilly, a native of West Texas, said playing in the game hurt his lungs to the point where he quit smoking cigarettes, a common habit among players of the time. “I’ve never been able to smoke a cigarette again,” he said. “In fact, I can’t even be in a room of smokers. I can’t breathe.”

Cowboys running back Dan Reeves also had a life-changing moment. In the third quarter, Reeves was trying to get outside on a sweep when he smashed into Ron Kostelnik face first and then into the ground, snapping off his facemask. At first he thought he lost some teeth. He later realized that his teeth were intact, but two of them were sticking through his frozen upper lip. “There was no blood,” he said. “It was too cold.” Reeves said he remembers the Ice Bowl “every time I shave” because he can see the scar under his left nostril.

Had the Cowboys won, Reeves could have been a hero. On the first play of the fourth quarter, he stunned Green Bay’s defense by throwing a halfback option pass to Lance Rentzel that gave the visitors a 17–14 lead. Reeves went on to play and coach in nine Super Bowls, working as an assistant under Landry and as head coach for the Denver Broncos, Atlanta Falcons, and New York Giants.

Former Giants star-turned-broadcaster Gifford received permission to do interviews in the losing locker room after the game, which was not a common practice at the time. Gifford, who knew Cowboys quarterback Don Meredith, asked what it was like to be in the loser’s locker room. “Look around,” Meredith said. “There is not a single loser in this room.”

The interview caught the attention of important people watching at home. Johnny Carson invited the duo to New York to appear on The Tonight Show. Meredith was so good on that stint he was invited back. He went on to guest host the show, and another spectator was Roone Arledge. He went on to produce Monday Night Football at ABC and hired both Gifford and Meredith to be in the booth.

Iconic Photo

John Biever, a 16-year-old Packers fan from Port Washington, Wisconsin, attended the Ice Bowl, and it changed his life. Biever’s father, Vernon, was the Packers team photographer. John would tag along during games, readying the film and equipment and occasionally snapping photos of his own. As the game wound down, the Bievers were positioned in the south end zone. Vernon decided to head to the Packers’ sideline, anticipating a reaction shot of Vince Lombardi and players either celebrating or being dejected.

John was left to chronicle the closing plays. He took aim with his dad’s Nikkormat single-frame camera with a 135-millimeter Tokina lens and clicked off three photos. The middle one of the series captured a pile of players—Bart Starr lying in the end zone, Jerry Kramer to his left (having cleared Jethro Pugh out of the way with one of the more famous blocks in history), and Chuck Mercein over the top with his arms outstretched—and is one of the iconic images in sports history. “It happened fast,” John Biever said. “Luckily, I wasn’t blocked by the referee.”

John Biever went on to work for the Milwaukee Journal and Sports Illustrated. His brother, Jim, succeeded his father as the Packers’ team photographer. He took hundreds of memorable photos, but none were talked about as often as “the Sneak.” Walter Iooss Jr., and Neil Leifer, two legendary photographers who later worked with John Biever at Sports Illustrated, also got the shot. Perhaps anticipating a rollout pass, Leifer was positioned on the sideline. Iooss was near John Biever, but his shot captures the scene moments after Biever’s, which has become the signature shot from the game.

One of the most important features of Biever’s picture was Packers fullback Mercein with his arms stretched over his head. It appears that Mercein, who had been acquired after Elijah Pitts (Achilles tendon) and Jim Grabowski (knee) were injured in a November 5 loss to the Baltimore Colts, was signaling a touchdown. He wasn’t. “As soon as I saw I wasn’t getting the ball, my worry was: don’t assist Bart,” he said. “It was very hard to stop, so I raised my hands in the air to show I didn’t push him because it would have been a penalty and it would have been catastrophic.”