World War II was the largest and most costly conflict in history, the first true global war. Fought on land, on sea, and in the air, it involved numerous countries and killed, maimed, or displaced millions of people, both civilian and military, around the world. In spite of the alliances that bound many of the same participants, the war was essentially two separate but simultaneous conflicts: one involved Japan as the major antagonist and took place mostly in Asia and the Pacific; and the other, initiated by Germany and Italy, was contested mainly in Europe, North Africa, the Mediterranean, and the Atlantic.

Although authorities differ over the starting date of the war in Asia, many consider its beginning to be September 18–19, 1931, when the Japanese Kwantung Army began its seizure of Manchuria from China; indeed, some Japanese scholars refer to the conflict on the Asian mainland as the “Fifteen-Year War,” lasting from 1931 to 1945. A number of historians judge the war’s start to be July 7, 1937, when heavy fighting broke out in northern China between Japanese and Chinese forces. Others use the dates of December 7–8,1941, when Japan’s attacks on British, Dutch, and United States territories in Asia and the Pacific brought the West into the conflict. Many of the countries opposing Japan also fought Germany and Italy in hostilities that formally started when Germany invaded Poland in September 1939 and ended with Germany’s defeat in May 1945, Italy having surrendered in September 1943. The war with Japan continued until the Japanese capitulation in August 1945 and formal surrender in September.

Nine of the Allied nations that had declared war against Japan signed the Japanese surrender document in Tokyo Bay on September 2,1945: Australia, Canada, China, France, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R), the United Kingdom, and the United States. Two other important Allies were India and the Philippines, which became independent countries after the war’s end. Of these 11 nations, all but China and the Philippines were also deeply involved in the war against Germany. The last to enter the conflict with Japan, the Soviet Union, invaded Japanese-held Manchuria early on August 9, 1945. The principal peace treaty with Japan was concluded in September 1951 and signed by 48 countries.

Of immense value to the Allied side was the extremely effective wartime alliance developed between the United States and the United Kingdom, closely bound by economic and historical ties. U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill had established the basis for the coalition before the United States entered the war and developed their close friendship during a number of wartime strategic conferences. Following the Japanese attacks in December 1941, the American and British military heads formed the Combined Chiefs of Staff to coordinate global strategy and share resources. Some of the other Allied powers, such as Australia, resented their exclusion from the highest levels of decision making but participated fully in and made essential contributions to the war effort.

As a member of the Axis powers, Japan was allied with Germany and Italy but did not collaborate strategically with the European Axis members. German leaders did not advise Japanese officials of their plan to invade the Soviet Union in June 1941. Similarly, Japan did not inform its allies in advance about its attack on U.S. forces at Pearl Harbor in December 1941, although in its aftermath, both Germany and Italy declared war against the United States, which had not been officially involved in the war in Europe up to that time. The Axis countries maintained diplomatic relations and traded strategic raw materials and technology in a limited way, but they did not coordinate their separate wars. In spite of Germany’s declaration of war against the Soviet Union, Japan continued to adhere to its neutrality pact with the U.S.S.R. until the Soviet attack near the end of the war. The U.S.S.R., in turn, resisted American and British pressure to go to war against Japan until the summer of 1945.

In addition to the Axis members, Japan formed alliances with the puppet governments established in its occupied areas. In early 1942, Thailand’s pro-Japanese government declared war against the United States and the United Kingdom; the United States declined to recognize Thailand as a belligerent, although the United Kingdom did. Additionally, Japan sought to promote and exploit the anti-Western and anticolonialism sentiments of many Asians, including nationalist groups that had worked for independence before the outbreak of war. Using the slogan “East Asia for the Asiatics,” Japan tried to raise support for its Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere. None of Japan’s Asian partners contributed substantially to the Japanese military cause.

For several centuries Japan successfully avoided contacts with the West, as the major European colonial powers gained access to China’s ports and strategic resources. In the 1850s, Japan’s leaders chose to cope with the Western incursion in Asia by bringing the nation to world-power status through industrialization, military modernization, and colonization. During the final half of the 19th century, Japan not only underwent a remarkable transformation economically and militarily but also developed ambitions to dominate the colonization of East Asia and the West Pacific. Japan’s growing power and audacity astonished most Westerners when it defeated China and Russia in 1895 and 1905, annexed Korea in 1910, and four years later grabbed Germany’s colonies in the Central Pacific and on China’s Shantung Peninsula. The conquest of all of China and further continental expansion became priorities in Japanese strategic planning. By the late 1920s, Tokyo focused its attention on Manchuria, which both China and the U.S.S.R. claimed. Rich in mineral and agricultural resources, it appeared an ideal solution to Japan’s serious overpopulation problems. In a short but ominous war beginning in September 1931, Japan’s Kwantung Army routed Chinese forces in Manchuria and renamed it Manchukuo. Neither the Soviet Union nor the West responded militarily. When the League of Nations condemned the aggression in Manchuria, Japan withdrew from the organization.

Encouraged by earlier expansionism and by reports exaggerating the disunity in China, Japan provoked war in July 1937. At the Marco Polo Bridge near Peking on the night of July 7, Japanese troops conducting army maneuvers exchanged fire with Chinese soldiers. As each side increased the size of its forces in the area, the original minor incident escalated into general warfare. In Tokyo, the militarists in control of Japan’s foreign and military policy anticipated a three-month campaign to force China’s capitulation. Instead, the Japanese armed forces made disappointing progress inland, although after heavy fighting, they captured the port city of Shanghai in November and Nanking 150 miles to the northwest in December. In the wake of Nanking’s fall, Japanese soldiers turned to rape, murder, pillage, and other atrocities, killing many civilians. The Chinese moved the capital from Nanking to Chungking, and both Chinese Nationalist and Communist leaders vowed to suspend their civil war and fight the Japanese until they left China. The Japanese gradually gained control of much of the coast and northeastern China, but Chinese defenses largely held in the mountainous interior.

By September 1939, when Germany’s invasion of Poland set off the European phase of World War II, the indecisive conflict in China had worn down Japan’s armed forces and military supplies. Still committed to its continental conquest, Japan’s leaders deliberated about a move into Southeast Asia, especially the Netherlands East Indies, where they could obtain the rubber, oil, and other raw materials essential to maintaining their war machine in China. Such a decision would mean war with the British and Dutch governments, which were the colonial overlords of the targeted areas, but their ability to stop Japan would be hampered enormously by the war in Europe. Much of the Japanese high command, especially army officers, preferred to seize the holdings of the U.S.S.R. across the Sea of Japan, which they had long coveted; the Kwantung Army in 1938 and 1939 had engaged in border skirmishes with Soviet troops at Changkufeng and Nomonhan. With its soldiers in China bogged down in a stalemate, Japan decided in favor of a strike in Southeast Asia and postponed indefinitely plans to seize Soviet territories in Northeast Asia. In April 1941, Japan signed a nonaggression pact with the U.S.S.R., which would ostensibly protect Japan’s northern flank if it launched a strike southward. The two countries remained at peace until the final days of the war, when the Soviets made a massive, surprise attack on Japanese forces in Manchuria.

Japan’s ambitions put it on a collision course with the strategic interests of the United States. Since the turn of the century, the linchpin of American foreign policy in the Far East had been to maintain the Open Door policy, which supported China’s territorial and administrative integrity, sovereignty, and independence. The policy also pledged the United States to protect equal trade and commercial conditions for all nations dealing with China. By its bold, aggressive moves, especially since 1931, Japan obviously intended to make China a part of the Japanese Empire, in direct conflict with American policy. From February to December 1941, talks between the U.S. secretary of state and the Japanese ambassador repeatedly broke down over Japan’s refusal to remove its troops from China and to endorse the Open Door principles. Although deeply involved in a struggle for survival against the European Axis, the United Kingdom gave the United States moral backing in its no-compromise stand on China. In April 1941, President Roosevelt announced that the United States would send to China lend-lease aid in the form of ground, sea, and air weapons as well as foodstuffs and other war relief as long as the conflict continued. “The arsenal of democracy,” as the immense American war production was called, would play a pivotal role in the ultimate defeat of Japan. In its initial impact, however, it inextricably entangled the United States in the mounting wars in Asia and Europe.

In addition to its China policy, Japanese plans clashed with other fundamental American strategic interests. The United States considered American access to Southeast Asia’s strategic raw materials to be essential in supplying the nation’s industry and in time of war its military establishment. Japan’s expansion into French Indochina in 1940 and 1941 posed a potential threat to that access as well as demonstrating continuing aggression; the United States responded by embargoing petroleum and other materials critical to Japan. Another basic premise of American policy in the Far East was its protection of the Philippine Islands, which it had acquired after the Spanish-American War of 1898. As the United States prepared the Philippines for independence in 1945, it continued to station American ground, sea, and air forces at bases in the archipelago. When tensions with Japan rose in the summer of 1941, the United States reinforced its military presence and nationalized the Philippine army.

As Japan’s high command planned its seizure of Southeast Asia, Admiral Isoruku Yamamoto, head of the Japanese Combined Fleet, insisted that the initial offensive should include a preemptive attack on the U.S. Fleet, which was stationed at Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands, another American possession. Japan had no intention of occupying Hawaii, but by devastating the fleet it sought to prevent the U.S. Navy from interfering with its conquests in Southeast Asia. Japan also decided to capture the Philippine Islands not to acquire raw materials but to deny its important strategic location and bases to the United States. The Japanese targeted the British bases at Singapore and Hong Kong for similar reasons and chose other sites to establish a defense perimeter around Japan’s holdings.

On the morning of December 7, 1941, Japanese planes raided Pearl Harbor, sank much of the U.S. Fleet, and killed 2,400 Americans. Within a few hours, Japanese forces also attacked the Malay peninsula, Midway, Hong Kong, and the Philippines. The United States and the United Kingdom formally went to war with Japan the next day. On December 11, Germany and Italy, which were allied with Japan through the Tripartite Pact, declared war on the United States and presented the American military with a two-ocean war. American isolationist sentiment vanished immediately as the country began to mobilize.

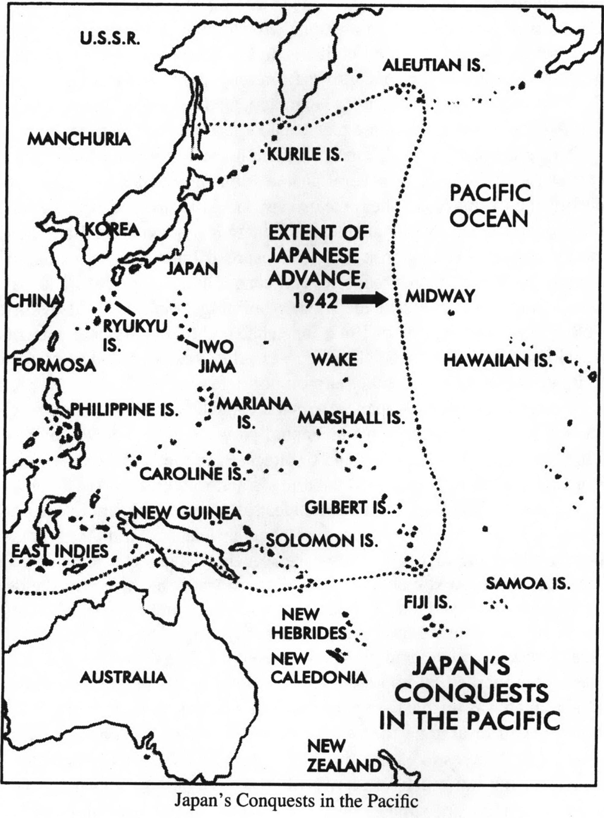

During the initial six months of Japan’s war with the West, Japan ap peared almost invincible as its forces moved rapidly through the Far East and inflicted one defeat after another on the Allies. From the British it seized Hong Kong, Malaya, Singapore, Burma, and British Borneo, and one of its fleets raided the Indian Ocean, normally a British preserve. It captured the Philippines, Guam, and Wake Island from the United States. The Japanese overwhelmed the Allied forces helping the Dutch defend the Netherlands East Indies and also moved into the Bismarcks, the Gilberts, and parts of New Guinea. In its rapid acquisition of territory, Japan took prisoner thousands of Allied civilians and military personnel, including especially large numbers of captives from Singapore, the Philippines, and the East Indies. As it advanced, Japan appeared poised to threaten India and Australia, where Japanese planes had already raided Darwin.

During the same period, Japan initiated no major operations in China except for the seizure of several airfields, but it advanced its cause by closing the Burma Road, the route used by the Allies to send military supplies to the Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek. The Allies could mount no effective response to the widespread Japanese expansion, although the United States made several carrier attacks against Japanese-held islands and launched the morale-building Doolittle Raid against Tokyo. By the late spring of 1942, Japan had greatly overextended its imperial boundaries, as its quick conquest of the Western colonies created a situation that it could neither exploit nor defend.

In early May 1942, a Japanese armada carrying a large invasion force moved toward Port Moresby in Papua, New Guinea, a location from which Australia could be isolated or attacked. In the Battle of the Coral Sea an Allied force intercepted the armada and fought the first all-carrier engagement of the war. While both sides sustained significant losses, the Japanese force retreated to its base at Rabaul instead of continuing its mission, marking the first time during the war that a Japanese advance had been halted. The next month, after landing troops in the Aleutian Islands, the Japanese received their first important defeat in the Battle of Midway, where American naval forces destroyed many of the Japanese Combined Fleet’s vessels and veteran pilots and caused the fleet to withdraw.

Midway marked an important turning point in the Pacific War, after which Japan was unable to expand further its defensive perimeter and the Allies began to assume the offensive. While Japan had committed its main ground forces to China, the Allies chose to aid China with materials of war but not much Western manpower. Deciding against a continental axis of advance, the United States struck back at Japan through the Pacific, thus exploiting the great American advantages in carriers, submarines, amphibious assault craft, enormous land-based air power, and maximum assistance from Australia and New Zealand.

The first major Allied offensives began in August 1942 in the southern and southwestern Pacific with attempts to capture Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands and the Papuan peninsula of New Guinea. Both campaigns were hard-fought and lengthy, lasting until early 1943 and demonstrating to the Allies the tenacity of the Japanese soldiers, even when fighting in situations they could not win. As would be the case throughout most of the island campaigns, few, if any, of the Japanese soldiers surrendered. In June 1943, also in the same Pacific regions, the Allies launched Operation Cartwheel to neutralize the important Japanese bases at Rabaul, northeast of New Guinea. Involving one approach through the central and northern Solomons and a second route along the northern New Guinea coast, the operation ended in the spring of 1944 with Rabaul effectively isolated and rendered ineffective.

Elsewhere in the Pacific, Allied forces in the north recaptured the Aleutian Islands in May and August 1943. While Cartwheel was still under way in November 1943, the Allies opened the second part of their dual advance toward Japan with an offensive to take the Gilbert Islands. Beginning with this campaign, U.S. forces would invade a series of island chains in their drive through the central Pacific toward Japan, while forces farther south would continue to move west along the New Guinea coast to the Philippines. On the continent, Allied soldiers launched offensives into Burma in late 1943 and early 1944.

Once the Allies had penetrated the long outer line of Japanese defenses from Burma and the East Indies to the Aleutians, the rest of the war was characterized by relatively free advances between large but disconnected enemy strongholds in the Pacific. The Allies bypassed isolated garrisons and focused on strategic Japanese bases that in Allied hands could become stepping stones for leaps farther along the axis to Tokyo. Japanese troops continued to resist fiercely, resulting in extremely bloody battles with heavy casualties on both sides. In late January 1944, the offensive in the central Pacific resumed with the Allied assault on the Marshall Islands, the first important territory retaken that Japan had controlled prior to the Second World War. Following the capture of the Marshalls, Allied forces in the central Pacific invaded the Marianas (June–August 1944), the Palaus (September-November 1944), Iwo Jima (February–March 1945), and Okinawa (April–June 1945). In the Battle of the Philippine Sea (June 1944), the Japanese task force sustained heavy damage and lost many of its planes and pilots.

In the southwestern Pacific, Allied forces in New Guinea bypassed large Japanese garrisons and advanced to the northwestern end of the island by the end of August 1944. While Australian troops remained in New Guinea to eliminate the remaining Japanese forces, American troops took the island of Morotai the next month and began the recapture of the Philippine Islands with an assault on Leyte in October. The landing in the Philippines set off the Battle for Leyte Gulf, the largest naval engagement in history, in which the Japanese Combined Fleet suffered such heavy losses that it could not effectively fight another surface engagement. During the Leyte landings, the Japanese first used kamikazes in organized attacks, a type of warfare they would increasingly employ during the rest of the war in place of their declining naval forces. The invasion of Luzon, the Philippines’ largest and most important island, started in January 1945 and continued until the end of the war. During the spring and summer of 1945, American troops began the liberation of the southern Philippine Islands, while Australian forces assaulted Japanese-held areas previously bypassed and captured several sites on Borneo.

On the Burma front, Allied troops blocked Japanese counteroffensives toward British bases in India and continued their own movement into Burma. In January 1945, the land route from northern Burma into China reopened with the completion of the Stilwell (Ledo) Road from India. The Allies completed their recapture of Burma that May. In China, the Japanese launched Operation Ichigo, their most important ground offensive during the last stage of the war. Beginning in April 1944, the Japanese operation successfully captured air bases used by American bombers and advanced rapidly through eastern and central China, meeting little resistance from the Chinese Nationalist troops. In the spring of 1945, Japanese units began to withdraw to northern China, where the high command feared the Soviet Union might attack.

In addition to seizing territory from Japan, Allied forces blockaded the home islands and increasingly used long-range submarines and bombers to intercept Japanese ships carrying troops and supplies between Tokyo and its garrisons across the Pacific and Asia. In the summer of 1944, the Americans instituted their strategic air campaign against Japan. At first, American B-29 bombers traveled from India to bases in China, from which they attacked Japan and its holdings. In late November 1944, after the United States had built airfields on the newly captured Mariana Islands, the air campaign escalated; eventually all of the B-29s were based in the Marianas. The strategic bombing of the Japanese home islands caused widespread destruction of lives and homes, especially after the Americans began to use incendiary bombs against Japanese cities.

Although Japan’s position appeared untenable as Allied forces moved closer to the home islands, destroyed the bulk of its navy, blockaded the country, and bombed its cities and industries, Japanese soldiers fighting the Allies showed no increased willingness to surrender. The last major campaigns in the Pacific—Okinawa, Luzon, Iwo Jima, and Leyte—were also the most costly in Allied lives. Many American strategists became convinced that a ground invasion of Japan would ultimately be required to force the country to surrender, although they anticipated that such an assault would result in many deaths on both sides. When the war in Europe ended with Germany’s collapse in May 1945, Allied countries began to shift their air, ground, and naval forces to the Pacific War in preparation for a ground assault on Japan’s home islands. Preliminary plans called for the invasion of Kyushu in the autumn of 1945 and Honshu in the spring of 1946.

The ground invasion of Japan became unnecessary, as the war underwent radical changes in August 1945. On August 6 and 9, American planes based in the Marianas dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Late on August 8, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and the next morning moved its forces into Manchuria, overwhelming the defending Japanese troops. With the Japanese leadership in Tokyo divided on the question of surrender, Emperor Hirohito personally intervened to decide the country’s capitulation. Japan formally surrendered on September 2,1945, in a ceremony on the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. The debate continues as to whether the two atomic bombs or the Soviet entry into the war against Japan had the greater influence on Japan’s decision to surrender.

Before the Japanese attacks of December 1941, Anglo-American leaders had already formulated the “Europe First” strategy to be followed if the United States fought against both Japan and Germany at the same time. They agreed that the United States and the United Kingdom would maintain the defensive in Asia and the Pacific until achieving victory in Europe; they would then shift their primary focus to Japan. In reality, although the Americans did indeed place the priority on the war in Europe, they also initiated offensives against Japan in the Pacific, which the British had agreed to consider an American strategic responsibility. Until the end of 1943, when the United States began to ship tremendous resources to Europe in preparation for the invasion of France, the numbers of American troops, planes, and ships in Asia and the Pacific roughly equaled those deployed against Germany. Thereafter, although Europe remained the most important combat theater, the American mobilization of troops and production grew large enough to support massive Allied offensives in the Pacific at the same time. Allied operations on the Asian mainland continued to receive a lower priority.

In addition to modifying the Europe First strategy during the course of the war, the United States also amended its prewar concepts about a war with Japan. For many years, American strategic planners had recognized the possibility of an American-Japanese clash in the Pacific and had anticipated that it would be essentially a naval war, relying on a series of amphibious assaults to capture Pacific island sites for naval bases closer to Japan. Although prewar plans called for a single advance of American forces from island to island across the central Pacific toward the Japanese home islands, the strategy adopted during the war consisted of a dual advance of Allied forces: one originating in August 1942 in the southern and southwestern Pacific and the other, initiated in late 1943, using the central Pacific route. The islands seized by amphibious assaults provided not only naval bases but also airfields for the strategic air campaign and staging grounds for the projected invasion of Japan. The Allies bypassed and neutralized Japanese strongholds such as Truk and Rabaul.

Prior to the war, both American and Japanese naval leaders shared the belief that battleships would mainly determine the outcome of any conflict between the two and gave little attention to the potential roles of aircraft carriers and submarines. After the war began, the carrier quickly superseded the battleship as the most important American surface warship, a process hastened by the Japanese sinking of most of the U.S. battleships on the first day of the war. Submarines also became extremely important to the United States, which, like Japan, initially considered their primary function to be supporting the surface fleet and attacking enemy warships. The American change of the submarine’s main target from Japanese warships to merchant shipping proved highly successful, aided by improved torpedoes, Japan’s failure to employ antisubmarine measures to protect its ships, and the Allied breaking of Japanese shipping codes. Japan, in contrast, employed its submarines piecemeal against warships and increasingly used them for transporting men and supplies in areas where the Allies controlled the air and the surface waters, instead of attacking the Allied lines of communication.

After the war with the West began, Japan continued to follow its continental strategy, focusing primarily on Asia in spite of the unanticipated course of the hostilities in the Pacific. Japanese planners had expected that Japan’s sudden immobilization of the U.S. Fleet in December 1941 and its rapid seizure of Southeast Asia would result in a quick negotiated peace that would leave Japan in control of the strategic raw materials it sought. When the Allies showed no signs of capitulating and defeated the Japanese navy in the Battle of Midway in 1942, Japan had no feasible plan for winning the war in the Pacific, where it was unprepared to fight a lengthy battle of attrition. Until the last days of the war, Japan continued to station the majority of its army troops in China rather than deploy them to the Pacific, where Allied drives increasingly threatened the home islands. The commitment of large Japanese forces on the continent was a principal factor in the United States’s effort to keep China in the war and preclude the transfer of more Japanese forces to the Pacific.

Exacerbating Japan’s situation were the intense rivalry and lack of coordination between its army and navy, which often had conflicting strategic goals and were not subject to a strong governing body. In 1937, Japan created the Imperial General Headquarters to direct the army and navy in the war effort, but its structure was too weak to resolve the differences between the two services. Additionally, Japan could not afford to waste its scarce resources on an inefficient command system. While the American effort in the Pacific suffered from interservice problems to a lesser degree, the oversight and coordination by the U.S. government and the Joint Chiefs of Staff prevented an adverse impact on the course of the war.

Although in December 1941 the Allies had few resources in the Pacific, the mobilization of the U.S. economy eventually produced overwhelming quantities of tools of war for the forces fighting Japan. Nevertheless, until nearly the end of the Asian-Pacific conflict, both civilian and military Japanese remained convinced that Japan’s Bushido code that emphasized honor, courage, and commitment to the emperor would give Japanese soldiers a spiritual edge in battle against the West’s material superiority, regardless of the vast American production in arms for ground, air, and sea warfare. In combat, Japanese troops fought tenaciously and refused to surrender, choosing instead to make banzai charges when overwhelmed by the enemy. Through the last major Allied offensives in the Pacific, which produced the heaviest casualties on both sides, Japanese soldiers showed no decrease in morale or willingness to fight to the death. During the same period, the Japanese further demonstrated their commitment through volunteering for formally organized kamikaze missions, inflicting substantial casualties and damage to Allied ships. Plans for the defense of the Japanese home islands included suicidal attacks by both soldiers and citizens.

Because critical shortages in men and matériel often dictated where and when military actions were undertaken in the Asian and Pacific combat zones, Allied strategy and logistics remained vitally linked until the final stage of the war against Japan. The conflict was a huge logistical enterprise for both sides, intensified by the hostile terrain and climate, widespread disease, the lack of roads and ports, and the enormous distances involved in transporting and supplying the war machine. Ultimately, the superior Allied logistical system proved crucial in the victory over Japan.

Allied logistical advantages included the Japanese failure to challenge enemy shipping, the huge production capacity of the U.S. economy, the employment of large numbers of cargo ships and transport planes, and the prewar attention given by the U.S. military to logistics, such as the at-sea refueling and resupply systems developed by the navy. Hindering the effort against Japan was the allocation of scarce resources to the war against Germany and Italy, in accordance with the Allied strategic priority on that conflict. The continuing shortages of shipping and landing craft, in particular, limited plans for offensive actions against Japan. The Japanese military leaders placed much less emphasis on logistics than did the Allies and were unprepared for the logistical problems accompanying the rapid expansion of the Japanese empire through much of Southeast Asia and the Pacific in late 1941 and early 1942. Although Japan had achieved its goal of capturing strategic raw materials, it could not fully exploit its acquisitions because of insufficient shipping, which also restricted its ability to resupply its widely deployed troops. As the war progressed, Allied attacks destroyed the bulk of Japan’s merchant ships, prevented food and raw materials from reaching the home islands, and further isolated Japanese garrisons throughout the Pacific.

During the war, a number of new weapons emerged, as well as scientific and technological advances that affected the conduct of the fighting. These ultimately proved beneficial to the Allies, whose cooperative research, access to raw materials, and enormous production capabilities enabled them to take advantage of new developments. Although in December 1941 Japanese fighter aircraft, destroyers, and torpedoes were vastly superior to those of the Allies, Japan later lacked the resources to produce its new designs and to match the wartime improvements introduced by the Allies. During the last year of the war, Japan’s situation was so desperate that it focused on the development of kamikaze and other special attack weapons.

One area of immeasurable importance was signal intelligence, or the ability to intercept and read enciphered messages transmitted by radio. By the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, the Allies had the capability to obtain “Magic” intelligence from the reading of high-level Japanese diplomatic codes. Eventually, they also acquired “Ultra” intelligence by breaking the main Japanese naval, army, and merchant shipping codes. Because of the enormous distances involved in the Pacific War, the Japanese relied especially heavily on radio to convey messages, giving the Allied code breakers a wide variety of information. Like the Germans, the Japanese did not know that their codes had been compromised and continued to use them throughout the war, while incorporating regular changes. Signal intelligence significantly aided the U.S. submarine war against Japanese merchant vessels and warships, as well as contributing enormously to the Allied victories in the Battles of Midway, the Bismarck Sea, and the Driniumor River. During the last months of the war, the intercepts revealed Japanese diplomatic attempts to end the war, as well as the extensive preparations for the defense of the home islands. Japan’s greatest achievements in signal intelligence involved Chinese codes.

Improvements in military medicine were especially significant in the battlegrounds of Asia and the Pacific, where troops of all nationalities suffered high rates of malaria and other diseases. The Allies instituted a strong anti-malarial campaign, including the use of atabrine as a preventive drug, and, during the last part of the war, widely applied the insecticide dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT). Two important Allied developments in the Pacific in 1943 were the introduction of penicillin and the institution of blood banks. Japan’s poor logistical system limited the provision of adequate medical care, as well as food, to its troops.

Among other important Allied advantages was radar, placed on U.S. aircraft carriers and newer submarines by December 1941 and added to other warships by the end of 1942. In contrast, Japan did not use it widely on surface vessels until late 1943 and on submarines until the following year. In the period before most Japanese warships carried radar, the technology helped the Allies significantly in the Battles of the Coral Sea and Midway, as well as during the Solomons naval campaigns. In ground and airborne radar also, the Allied employment was more advanced than Japan’s. The best airborne radar was installed on the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, a very long-range bomber designed for the strategic air campaign against Japan and first used in June 1944. Vital to the success of Allied amphibious assaults was the development and production of immense numbers and types of landing craft and ships.

Introduced by the Allies during the conflict were the proximity fuze, which enabled artillery shells, bombs, and rockets to explode on or close to targets; napalm, widely used in incendiary bombs and deployed by flamethrowers during the last year of the war; and the most famous new weapon, the atomic bomb, dropped on two Japanese cities shortly before the surrender. Under the auspices of the U.S. government, a massive secret wartime program known as the Manhattan Project designed and constructed the first atomic weapons. After the successful testing of the bomb in July 1945, President Harry S. Truman ordered the use of the weapon against Japan.

The estimated human costs of all of World War II are beyond comprehension: military dead and missing, 15 to 20 million; civilian dead and missing, 40 to 60 million; military wounded, 25 million; civilian wounded, 10 to 20 million; homeless, 28 million; prisoners of war, 15 million; civilian prisoners, 20 million. Disease, malnutrition, poor living conditions, and inadequate medical care caused the deaths of millions more. Military operations and occupations created countless refugees, while other civilians were transported long distances to work as forced laborers.

Precise statistics are unavailable for the casualties in Asia and the Pacific; however, by any evaluation, the costs of the war with Japan were tremendous. The estimates for two of the countries invaded by Japan are indicative of the war’s impact. According to the Chinese Nationalist government, its military battle deaths from 1937 to 1945 were 1.3 million, while other sources place the total of Chinese civilian and military deaths as high as 15 million. The government of the Philippines, which Japan occupied in whole or part from 1941 to 1945, claimed that more than one million of its citizens were killed by enemy action, with 100,000 civilians dying during the Battle of Manila alone.

The figures concerning the armed forces of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States are among the most reliable statistics, although each country, and often each of its service branches, used different criteria for its counts. During the war against Japan, nearly 150,000 military personnel from these countries were killed in action or died as prisoners of war. The U.S.S.R., in its 1945 campaign in Manchuria, sustained 8,000 battle deaths. Of the other Allied belligerents, India and the Netherlands also suffered heavy losses, including large numbers of prisoners captured in the first months of the war. Most of the surviving Allied prisoners spent more than three years in captivity.

Japanese sources estimate that 2.3 million Japanese military and civilian personnel working for the military were killed in combat from 1937 to 1945. Soviet forces invading Manchuria in August 1945 captured from one to two million Japanese; the U.S.S.R. delayed their repatriation for years and never accounted for 300,000 people to the satisfaction of the Japanese government. According to the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, 330,000 Japanese civilians in the home islands died between late 1944 and the end of the war as a result of the Allied strategic air campaign, including the use of two atomic bombs.

In addition to the deaths, the physical devastation in East and Southeast Asia and the western Pacific was immense, including not only the sites of military operations but also many of the areas occupied by Japan during the war. The ruined economies throughout the region could neither feed nor house the inhabitants. In Japan itself, the strategic bombing caused enormous material destruction and dislocation. The U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey reported that the air campaign’s attacks on 66 Japanese cities had destroyed 40 percent of their most densely built areas. The bombs and the resulting firestorms ruined 2,510,000 buildings and left homeless 30 percent of the urban population. Before the war ended, 8.5 million Japanese had moved from the cities to the countryside to avoid the bombing. Six million Japanese, including both military and civilian, were overseas at the time of the surrender, in addition to massive numbers of Korean and Chinese laborers forced to work for the Japanese.

Within five years of the war’s end, a number of new nations had been created, and others were in the throes of armed conflict, as the political and military administration of much of Asia and the Pacific underwent sharp changes. At the time of the surrender, Japan still controlled vast territories outside the home islands. As Allied forces began to reoccupy the areas administered before the war by European nations, they encountered resistance—sometimes violent—to the reimposition of colonial control. In some areas, the nationalist movements had been well established before the war, while others originated as opponents to Japanese control during the conflict. Japan’s encouragement of anticolonialism as part of its “Asia for the Asiatics” campaign led to collaboration with nationalistic groups in such areas as the Netherlands East Indies, where Japanese forces turned their arms over to the Indonesians rather than the Allies at the end of the war.

The new nations achieved independence through a variety of means. The United Kingdom, which had incurred massive debt during the war and could no longer afford its vast empire, responded to nationalist movements and granted independence to India (1947), Pakistan (1947), Burma (1948), and Ceylon (1948). In Malaya, the federation created by the British in 1948 became independent years later after the defeat of communist insurgents, mostly ethnic Chinese, who had led the resistance during the Japanese occupation. The Netherlands reluctantly recognized the statehood of Indonesia in 1949, after sustaining heavy casualties in an especially violent conflict over the Dutch attempt to reassert their authority. In Indochina, France became involved in a lengthy, ultimately unsuccessful attempt to retain its colony. In a peaceful process instituted by the United States before the war, the Republic of the Philippines became a new country in 1946.

Following the liberation of Korea from decades of harsh Japanese rule, two new countries were established on the peninsula: the Republic of Korea in the south, sponsored by the United States; and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in the north, whose communist government was backed by the U.S.S.R. In the Pacific, the United States became the trustee for a number of archipelagos formerly controlled by Japan: the Ryukyus (including Okinawa), the Volcanoes (including Iwo Jima), the northern Marianas, the Carolines, and the Marshalls; the Ryukyus and Volcanoes were later returned to Japan.

In a political shift of enormous proportions, the Chinese Communists won their lengthy civil war and ousted the Nationalists from power in 1949. The Nationalists moved to the island of Formosa and continued to use the name “Republic of China.” On the mainland, Mao Tse-tung proclaimed the formation of the People’s Republic of China. The Western Allies, especially the United States, judged the Communist victory in China an immense blow to the stability of the region, especially considered in conjunction with Communist strength in areas such as North Korea, Indochina, Malaya, and the Philippines. With the cold war between the U.S.S.R. and the United States and their allies already well under way, U.S. policy changed from the wartime encouragement of decolonization, as enunciated by President Roosevelt, to the support of colonial powers, such as France in Indochina, to halt the spread of communism. Strategically, the United States gave the priority to Europe in continuation of its wartime policy, but American involvement in Asia increasingly deepened. When war broke out in Korea in the summer of 1950, the United States became heavily involved.

The rise of communism in Asia strongly impacted the course of the military occupation of Japan. In accordance with the surrender agreement, Allied military forces occupied Japan at the close of the war and remained there until the Japanese peace treaty took effect in the spring of 1952. Although the occupation was nominally an Allied effort, it was dominated totally by the United States. Presiding over the occupation as Supreme Allied Commander for the Allied Powers was U.S. General of the Army Douglas MacArthur. During the first two years, the occupation was basically punitive and reformist, working to demilitarize and democratize Japan, while conducting war crimes trials, overseeing the repatriation of millions of Japanese nationals and foreign workers, and purging militaristic and ultranationalistic officials from the government. During this phase, Japan adopted a liberal, democratic constitution written by MacArthur’s staff. As the cold war intensified and the Chinese Communists made significant gains in 1947–1948, the U.S. government decided to reverse its course regarding the occupation and attempt to build up Japan as an economically strong state that could serve as a “bulwark for democracy” in Asia. In September 1951, as the end of the occupation neared with agreement concerning the terms of the peace treaty, the United States concluded a military alliance with Japan. During the same month, the United States also signed a defense treaty with Australia and New Zealand.

In an attempt to maintain global peace, the Allied countries in 1945 established the United Nations (UN) organization as a successor to the League of Nations, which had for a variety of reasons totally failed to deter the aggression in the 1930s that culminated in World War II. Prior to the U.S. entry into the war, President Roosevelt had joined Prime Minister Churchill in issuing the Atlantic Charter, which enunciated the principles that formed the basis for the UN. The charter advocated self-government, economic collaboration, and access to trade and raw materials for all nations, as well as renouncing territorial gains. In January 1942, 24 countries joined the United States and United Kingdom in signing the Declaration of the United Nations, which affirmed the Atlantic Charter and pledged to defeat the Axis powers. The concept of an international body was further developed at wartime conferences held in Moscow, Dumbarton Oaks, and Yalta. In April 1945, the signers of the Declaration of the United Nations, now grown to 50 countries, met in San Francisco to consider the United Nations charter, which they adopted on June 26, 1945.

In spite of the massive Allied effort to defeat Japan, Japan’s surrender did not immediately end the political, economic, and social turmoil in Asia and the Pacific. Although Japan renounced war in its 1947 constitution, conflict continued across Asia, as former colonies fought for independence and civil war engulfed other areas. Further overshadowing the rehabilitation of devastated economies and landscapes were the developing cold war and the prospect of nuclear warfare.