Something about Escalante Bay had always been very calming to me. I loved the rhythmic motion of the rolling waves washing over the dull red sand on the beach. The wind was strong and fresh, its briny scent masking the memory of the acrid stench of factory smoke. Just being here by the bay made my problems seem to disappear.

Beside me, Tamara had yanked off her shoes and rolled her leggings halfway up her calves. She sat close enough to the shoreline that occasional waves lapped over the tips of her toes. Neither of us said a word, but Tamara hummed to herself, running her fingers across the sand beside her like she was playing a keyboard.

“Did I tell you that I got my first official gig?” she said suddenly.

“What? No! Where at?”

“Museum opening. That big building they’ve been building on Sparta Island, the one with all the columns in front. It’s an art museum, but I heard they’re opening with an archaeology exhibit—‘classical art of the ancient world’ or something.” She grinned at my dumbstruck expression. “Up your alley, huh?”

I nodded, rubbing the back of my neck with my left hand. “You know it. But what about you? You’re singing?”

“Yeah, they’re having some kind of hoity-toity Grand Opening banquet for the board of trustees in June. Supposedly the Governor’s going to be there. They want me to play and sing.” She wiggled her fingers, miming the keyboard again. “I think they just invited me because of my parents. Mom is one of their donors.”

“Come on. You know that had nothing to do with it. You’re one of the most talented musicians in Tierra Nueva. How do you think you got into Herschel?”

She looked down, her long brown hair hiding her face, but I thought her ear looked sort of red. It was hard to tell in the near-darkness. “Well, I’d argue my moms again, but it’s nice to have a vote of confidence. I hope I don’t blow it.”

“You won’t. You’ll be stellar, for sure.”

Tamara’s toes dug into the silty sand, so fine that it was more like dust, really. She kept her gaze fixed on her feet as she said, “Do you want to come? With me? To the opening? I mean, not just to hear me sing, there’s the exhibit and stuff, too. They’ve got some Olmec artifacts, they might even have some of your grandpa’s…”

My heart jumped. I could barely hear my own voice over its hammering. “Of course I’ll come. Not… not just for the exhibit. For you.” Oh, Cristo, did I really just say that? Could I be any more embarrassing?

But then she grinned at me, and I couldn’t help but grin back.

Tamara leaned back on her hands. “So. What were you saying earlier? You thought you’d seen an arch like that before?”

I flushed. For a minute, I thought about just telling her to forget it—it was stupid and crazy. I knew that. But deep down, a little, tiny piece of me wanted to hear someone tell me that I wasn’t crazy. That maybe my mom was the one who was wrong, and that there really was more to that box of Dad’s than just a collection of Earth junk.

I shifted, digging down into my pocket to pull the coin out. “It’s probably stupid, but I thought it looked like this.”

I handed her the coin. She shifted onto her knees, holding the coin up to examine it in the glow of the fluorescent lamps on the wharf behind us. She squinted as she turned it over and back. “It does look the same. Look at the way the stones are stacked.”

“Right?” Eagerly, I scooted closer. “I mean, it’s probably just a coincidence, but still.”

She’d flipped the coin over again and was frowning at the markings on the reverse. “Where did you find this, again?”

“Henry and I found a box of my dad’s junk buried in the garden at the end of last summer.”

“This was your dad’s?”

“Yeah. Well, I think so. It was in this metal box that had a ton of other stuff that I know was his. I’d never seen it before, though. I figured he won it off one of his buddies at the factory or something.”

Tamara hesitated. “Maybe. But…” She stretched out her hand, the reverse side of the coin facing me. “Look at that.”

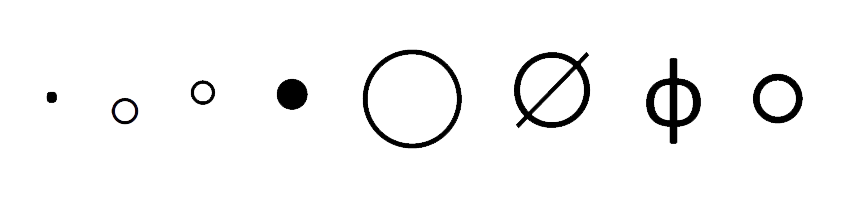

I peered at the nine engraved circles again. Looking more closely, I realized one of them was actually a star, not a circle. The other eight had oblong rings coming out of them, stretching around the coin. Eight circles, each of various sizes. The fourth from the center was a different color than the others. I took the coin back from Tamara and scraped my fingernail across it. It was tarnished, but it almost looked like gold.

I looked back up at Tamara. “The solar system?” I said.

“Right. And the central planet isn’t Earth. That’s Mars.”

I flopped back down on the sand. The breath had left my body entirely. “Mars?!”

Tamara snorted. “What are you acting so shocked for? You’re the one who thought it looked like the arch at Professor Gomez’s site.”

“Yeah, but… I thought I was crazy!”

“Congratulations, then—you’re as sane as I am.” She grinned like a Cheshire cat. Deimos winked over her shoulder, completing the effect.

The wind picked up, and a large wave gushed over the sand, soaking my shoes. The water was freezing, but I barely noticed.

Mars was a dead planet. There was no one here before us. Nothing but spider weeds, and weird little fish things, and underground germs. I knew that had to be true, because GSAF had done a study before they approved the planet for terraformation, to find out if the planet could sustain life or if there was anything here that could harm humans. I’d been hearing about it my whole life just from listening to Mom talk to herself while she worked. We all had to learn about this in sophomore biology class. Everyone knew this.

But what if they were wrong?

Santa torquing Maria.

Tamara got to her feet shakily, brushing the red sand off her leggings. She held out a hand to help me up, as I was none too sturdy myself.

“You know what, Isaak?” she said. “I don’t think I’m going to mind missing my weekend classes at Herschel after all.”

◦ • ◦

“So that’s why you didn’t go on Speculus last night, huh?” Henry asked. We were standing on the platform of the South Gateway station, waiting for the 7:20 train that we took to the Academy every morning. Groups of factory workers and commuters shuffled around us, yawning and taking huge swigs from plastic travel mugs. One scraggly-looking old man was vaping by the trash can, even though there was a huge sign a meter away from him prohibiting both vaping and smoking on the platform.

“Pretty much. Sorry, man. Not that I didn’t want to talk to you, but I kind of had too much on my mind to even think straight, let alone articulate.”

“Understandable. So, did you kiss her?”

I choked on my own spit. “I’m sorry, what?” I managed between coughs.

Henry shook his head, his sleek black hair flipping back and forth dramatically. “Ta-ma-ra. Did you kiss her, you moron?”

“Of course not!”

He sighed. “I don’t know what I’m going to do with you, Zak. If you don’t get your act together, someone else is going to make a move on her, and you don’t get to say I didn’t warn you.”

I spluttered indignantly. “I made a date with her, what more do you want? It’s not exactly like I had a chance to get super romantic, considering the fact that the very fabric of our existence has been challenged.”

“Blow it out of proportion, why don’t we?” said Henry. “We haven’t even seen much of that dig site, other than getting up close and personal with one hole—and GSAF’s security system. We can freak out after we find the underground kingdom of the Little Green Men. Let me see that coin.”

I’d already shown him once, but I dutifully produced the tarnished coin from my pocket once more. Henry frowned down at it. “Yeah, I guess it does look like that arch. But they had vaults like this in India, too, I know that much. So it could be from Earth.” He flipped it over to examine the solar system on the back. “This, on the other hand…”

“What’s that you have there, boy?” a throaty voice interjected. I looked up with a start. The vaper had wandered over to us, and he was leering at Henry now over the top of his hawkish nose.

Henry, ever polite, replied, “None of your business.” He accompanied this with a gesture.

“Don’t get testy, now,” the old man said, powering off his e-cig and buttoning it into his shirtfront pocket. His hair was white and unkempt, sticking out every which way in longish clumps like an even-crazier Albert Einstein. He wore a gray factory uniform like my dad’s old one, with the name Emil stitched onto the lapel in cursive writing. “It’s just that that looks like something of mine that went missing a few years back.”

“Pretty sure it’s not. Because we found it at his house.”

Henry pointed, and the scruffy man whirled on me. He narrowed his eyes for a long moment, and then said, “Contreras.”

The air left my lungs. “W-what?”

“You’re Contreras’ kid. You look just like him. Where’s your daddy, boy?” He moved close enough that I could smell his breath, a sour combination of cheap apple e-cig flavoring and tooth decay.

“He’s gone,” I replied shakily. “He left Mars two annums ago.”

“Don’t answer him!” Henry interjected.

I turned to respond, but Emil beat me to it, snapping, “Keep out of this, Paki!”

Henry moved faster than my eyes could keep up. One second he was standing on my left, the next he’d charged forward and his fist was sailing briskly toward the man’s jaw. Emil must have expected this reaction, though, because he ducked with practiced skill. He had good reflexes for someone who appeared to be in his seventies.

I grabbed onto Henry and attempted to drag him off the man, but it was difficult to keep my grip on him. Even though I was taller, I was also pretty skinny. Henry, on the other hand, was built like a tank—sturdy and strong.

“Henry, you can’t just beat up an old guy in the train station!” I shouted, pulling him back. “Do you want to get arrested?”

Henry replied by yelling something in Hindi at the top of his lungs. Mrs. Sandhu had definitely not taught me that phrase, but its meaning was pretty easy to figure out. The throngs of commuters had all turned their eyes on us, and a couple of men in business suits came rushing over, trying to help me break up the fight. Between the three of us, we managed to separate Henry and the factory worker.

“Take it back, you racist bastard,” Henry snarled.

“I will not. You need to keep your nose where it belongs. My business is with the Contreras kid.” Thrusting his jaw toward me, Emil hissed, “That coin of yours is stolen, boy. It belongs to me, and I want it back. And I want the key, too.”

One of the business suit guys looked up from straightening his cravat. “Look, buddy, if you’ve got a problem with these kids, you need to take it up with ADOT security. You can’t just go picking fights with teenagers on a train platform.”

As they argued, I heard the telltale clacking of the train on its way down the tracks. “Come on,” I said to Henry, and we hurried to the platform’s edge. The train coasted to a stop and we rushed through the sliding doors. I could hear the business suit guys calling after us, saying that security was on its way, but I didn’t want anything to do with that. I just wanted to get the heck out of there.

“What the actual…” Henry panted as we slumped into our seats.

“I have no clue. That guy was a fruitcake and a half.”

“You shouldn’t have told him anything about your dad.”

“You’re the one who told him we found the coin at my house!” I flopped back against the roughly upholstered seat, exasperated. “What was I supposed to do? He was all up in my face with his nasty-ass breath! And he knew my dad, and about the coin. He might have known where it came from. And what else was he on about? A key?”

“Gee, I dunno, do you want to go back and ask him?” Henry suggested snidely.

“Of course not. And I think we’d better find another train to take to school if that weirdo’s going to be there every morning.”

“No kidding. I just hope he doesn’t know where you live, dude.”

I hadn’t thought of that. He obviously had known my dad, but I didn’t know how well. The thought of Emil turning up on my doorstep was enough to give me nightmares for the rest of my life. I pulled up my palmtop’s phone app just to make sure it had emergency services saved on speed dial.

This stupid coin was causing me nothing but trouble. Maybe my mom was right—I should have let the whole thing go. But it was too late now. I was in it up to my neck.