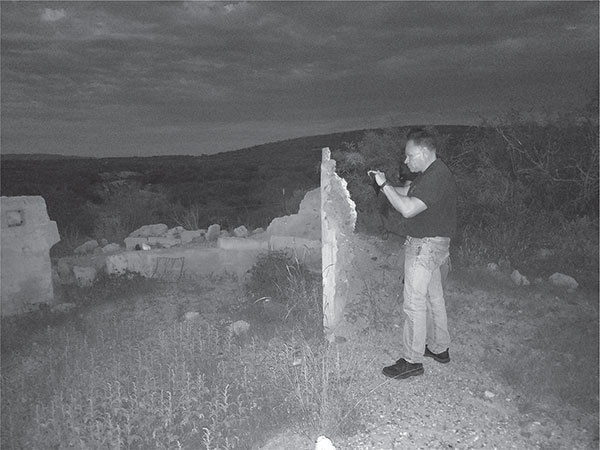

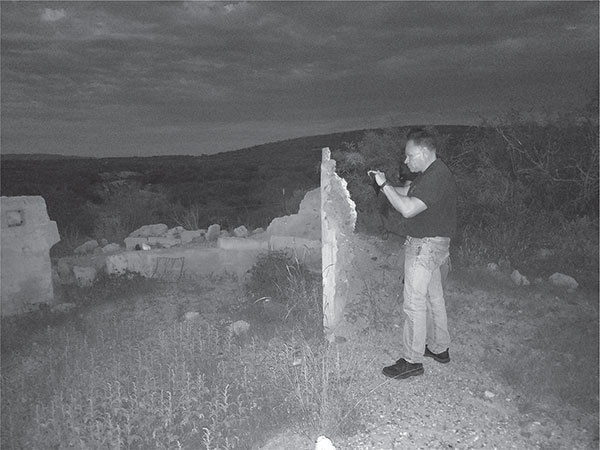

Donovan at the cabin ruins recording segments for the Ghost Patrol. Photo by the author.

3

BRUNCKOW CABIN

On the Charleston Road between Tombstone and Sierra Vista is the site of the old Brunckow Cabin. It is set about two hundred yards off the road on a bluff overlooking the river and is known as the bloodiest cabin in all of Arizona. At least twenty-one men were killed on this site, with seventeen of those being murdered between 1858 and 1880.

Many of those unfortunate souls are buried near the cabin itself, which makes this site an unofficial graveyard. This site was owned or used by men such as Fredrick Brunckow, Ed Schieffelin, Frank Stilwell and Milton B. Duffield.

Fredrick Brunckow was a German immigrant who was born in 1830 and immigrated to the United States in 1850. He was a native of Berlin and educated at the University of Westphalia and the School of Mines at Freiberg. After coming to the United States, he worked his way west, holding a variety of jobs until he met Charles Poston of the Sonora Exploring and Mining Company. Brunckow’s credentials were quite impressive, and he was soon hired. Poston was familiar with the tradition of Spanish silver mining in the San Pedro Valley, and he wanted a young, enterprising professional to prospect the area. Brunckow fit the bill and found silver in 1859. Shortly afterward, Poston sent him to New York to report his discovery and its estimated worth to the company’s stockholders. Then the young German came back to Arizona and began work on his mine. Several adobe buildings, including a store, were built. Two partners, William and James Williams, were brought in, and a force of miners and laborers was recruited in Sonora. It was a small but profitable operation. The great silver strike in the hills nine miles northeast, where Tombstone would eventually be founded, was still two decades away. If tragedy had not struck, it is very likely that Brunckow, not Ed Schieffelin, would have sparked the great days of silver mining in Cochise County. However, fate had a different plan.

On July 23, 1860, William Williams left the mine on horseback for Fort Buchanan, thirty-five miles to the southwest, to purchase a wagon load of flour. Left behind were Brunckow; James Williams, mining engineer and part-time keeper; a former schoolteacher from St. Louis named Morse; and David Brontrager, a cook.

At midnight three days later, Williams return to the mine, accompanied by the two young sons of a Sonoita rancher. The boys had the job of returning the wagon and team to the fort after the supplies were unloaded. As they approached the camp, Williams was puzzled because the sound of their arrival had not alerted any of the dogs that were kept at the camp. Suddenly, the three were stopped dead in their tracks by an ominous sign, the smell of death.

Cautiously, Williams dismounted and entered the store to investigate, using a lighted match to illuminate the area. The scene he found was one of horror. His cousin, three days dead, lay on the floor just beyond the entrance. The store itself was a wreck, looted of its merchandise. Fearful that the assassins might still be waiting in the darkness, Williams ran back to the wagon and told the boys, “Let’s get back to the fort, quick, more help!” The trio rode away, not looking back until they reached Fort Buchanan. Upon their arrival, Williams told the post commander about what he had seen. The commander immediately dispatched a detail of troopers to the scene.

Later that day, the cook, Brontrager, appeared at Camp Jecker, the field headquarters of the Sonora Survey Commission. He was exhausted, bruised and bloody and almost incoherent. He said that a massacre had taken place at the mine and it was the work of the Mexican miners. The killers had all fled to Sonora, and he was the only survivor. He told the troopers that soon after Williams left for the fort, two of the miners came into the kitchen and asked for a match to light their cigars. At the same time, there were gunshots outside, and the pack of dogs began to howl. Brontrager heard shouts and cries of terror and pain. He started for the door, but the miners barred his way.

“You are a prisoner,” they told him, “but we will not harm you because you are a good Catholic. We are all going to Sonora, with the goods from the store, and in time we will let you go.”

Several thousand dollars’ worth of merchandise that had recently arrived from St. Louis was the motive for the massacre, the cook said. As the Mexicans and their families departed with the loot piled high on the camp’s seven horses and mules, Brontrager saw the victims. James Williams was shot dead in the store. Morse, who also was killed by gunfire, was lying just outside. Brunckow had been stabbed to death at the mineshaft.

“The Mexicans turned me loose just before we got to the border,” Brontrager told the troopers, “and I have been wandering around here for four days.”

The cook was taken to Fort Buchanan, where the commander confined him to the guardhouse as a witness should the killers be caught and to protect him from several enraged citizens, who believed that he was an ally of the murderers.

By the time the soldiers arrived at the mine, the area had become even more gruesome. There was almost nothing left of Morse and Brunckow, as wolves had eaten the majority of their corpses. The decomposition of what remained of their bodies in the hot Arizona sun was so extreme that the bodies could only be identified by the clothing they were wearing.

“It made us all sick,” Sergeant Henderson later wrote in his report, “but with the help of whiskey and camphor we gave the deceased a good burial.” Initially, the newspapers put the murders on the local Apaches. This would change in early August when a courier brought a message from the commandant of the Santa Cruz District in Sonora to the commander at Fort Buchanan. The message revealed that a man named Jesus Rodriguez had been captured, and under interrogation, he leaked information about the massacre at the cabin. Rodriguez was a Brunckow miner who had been boasting of the murders in Arizona in several Cananea cantinas, disposing of his share of the stolen goods in the process. The other killers, Rodriguez said, had gone to Hermosillo.

The mine was deserted from the day of the massacre until October 23, 1873, when the claim was purchased by Milton B. Duffield, the first U.S. marshal appointed to Arizona Territory. Duffield was a controversial figure, which is one way of saying that a lot of people loathed and outright hated him. However, a man named James T. Holmes also claimed to be the owner. On June 5, 1874, Duffield arrived at Brunckow’s Cabin to evict Holmes from the property. As he approached, Duffield began “waving his arms and shouting like a madman.” Assuming that Duffield was armed and dangerous, and aware of his violent reputation, Holmes grabbed his double-barreled shotgun. He burst out the front door, and without the slightest bit of hesitation, shot the old lawman dead. It was at this point Holmes realized that his victim was unarmed.

Duffield was accorded an obituary in the Tucson Citizen, which read: “He has frequently marched through the streets like an insane person, threatening violence to all who had offended him. It is claimed by some men that Duffield had redeeming qualities, but we confess we could never find them.”

Duffield was buried somewhere around Brunckow Cabin, and his remains are still interred there to this day. His is just another one of several unmarked graves surrounding the cabin.

Holmes was soon arrested and tried for murder. He was found guilty and sentenced to three years in prison. However, he escaped before having a chance to serve any of his time. The local authorities did not make an effort to chase after him, and he was never seen in the Arizona Territory again.

When Ed Schieffelin, the man who founded the town of Tombstone, came into the area in 1877, he used Brunckow’s Cabin as a base of operations while he prospected the rocky outcroppings to the northeast. He smelted any ore he found in the cabin’s fireplace.

A few months later, Ed had worked his way over to Goose Flats, where he found the mother lode of silver and registered his claim under the name Tombstone because the U.S. Army soldiers stationed nearby had told him, “The only thing you will find out there is your tombstone.”

Frank Stilwell, one of the Cowboys who was known to be involved in the murder of Morgan Earp on March 18, 1882, also had a connection with the Brunckow Cabin and mine site. Stilwell, who had been a deputy sheriff under Johnny Behan, also owned several businesses. They included several mines, a saloon, a wholesale liquor business and even a stage line.

When he met his death at the hands of Wyatt Earp in the Tucson train yards, Stilwell was the recorded owner of the Brunckow mine site and some surrounding property.

On May 20, 1897, the Tombstone Prospector reported that Brunckow’s Cabin was the site where a gang of bandits fought over a Wells Fargo gold shipment that they had just acquired. However, the outlaws could not reach an agreement on how to divide the gold. The resulting argument led to violence, as they turned against one another and shot it out. According to the newspaper, all five of the outlaws were later found dead. The stolen gold was recovered at the scene and soon returned.

Over the next several years, many others have been found dead near the cabin. A man and his son, who were camping by the cabin one evening, were found dead several days later. A lone prospector who was exploring the mine was found near the cabin with a bullet in his back. An early settler of Tombstone told in his diary of finding a family of four massacred at the cabin, supposedly by the Apache.

In May 1897, the Tombstone Epitaph printed a ghost story that featured Brunckow Cabin and the haunted mine. It mentioned that every night, a menacing ghost was seen moving around the dilapidated adobe cabin. Several people attempted to investigate, but upon approaching near enough to speak, the apparition suddenly vanished, only to appear just as quickly at some other place, thus sending its pursuers on a lively and elusive chase.

The newspaper noted that some people reported hearing the sounds of mining coming from the shaft, such as “pounding on drills, pickaxes pulling away rocks, and the sawing of lumber for trusses.”

This account is echoed in another newspaper story published by the Tombstone Prospector on May 20, 1897:

The halcyon days of Tombstone are often brought to memory, and even at the expense of some unfortunate. It is a pleasure to allow the mind to revert back to the 80’s when this was surely the greatest mining camp on earth; when the shrill whistles of the numerous mines were deafening to the ear; when the bad man prevailed, and the music of his “gun” lulled many to sleep; when bold highwaymen plied when “life” began with the fading away of each day, and there was one continual round of pleasure. Crime then was regarded as a matter of course. Criminals held full sway, and it was a case of survival of the fittest. These reflections are brought to mind through the report of a spook which has taken possession of a long since abandoned mine. The history of which at once establish it as the appropriate habitation of ghosts. In the early days of Brunckow mine, three miles below Tombstone was the scene of much excitement; dissension arose among the owners and shooting affairs became numerous, occasionally a man was missing, and that ended it: one man was supposed to have been shot and thrown into a well, but as there were abundant men in those days an investigation was deemed needless. Five men were found at the Brunckow with their toes pointing heavenward at one time: it was an ideal rendezvous for the knight of the road. The five men found there were a party of freebooters who had raided a Wells-Fargo bullion wagon and fought over a division of the spoils. If such a thing be possible, then it is no wonder that the spirit of the departed should linger around the scene of pillage and carnage. Reputable men of Tombstone will vouch for the truthfulness of the statement that the mine is haunted. The story goes that every night can be seen a menacing ghost stalking around and through the dilapidated ’dobe shanty; people have attempted to investigate, but upon approaching apparently near enough to speak, the spook suddenly vanishes, only to appear as quickly at some other point, leading its would-be queriest a lively and illusive chase. There is apparently but one and when out to be seen, mining operations can be heard in the old shaft, pounding on drills, sawing lumber and working along ever and anon just as though silver had never depreciated. That there is some mysterious movements around the Brunckow is honestly believed by many here. Several of our sturdy plainsmen and mountaineers will visit this deserted mine and attempt an investigation.

In 1881, the Arizona Democrat also reported that “the graves lie thick around the old adobe house. Prospectors and miners avoid the spot as they would the plague, and many of them will tell you that the unquiet spirits of the departed are wont to revisit and wander about the scene.”

Ever since ghost hunting has become vogue, Brunckow Cabin has been one of the top locations that ghost hunters and paranormal investigators want to investigate. Even the television show Ghost Hunters has been to this site to do an investigation.

Donovan at the cabin ruins recording segments for the Ghost Patrol. Photo by the author.

Donovan’s Ghost Patrol has been out to the site of the cabin several times. During a ghost hunt in 2017, I was able to accompany them. On this particular trip, we went to do some audio recording that would be used on future segments for Donovan’s radio show. It has a unique ambiance that can be quite creepy.

While exploring the ruins, several of the investigators distinctly heard the sound of approaching footsteps. When we investigated the sounds, we found nothing. No people, no animals, just the darkness of the southern Arizonian night. The site itself can be quite dangerous, as there are several mineshafts in the area. I have been told that drug smugglers could be an issue as well. Not wanting to tempt fate, we finished the recordings and left the ghosts to their own devices.