Storefront on West Allen Street, 1933. Library of Congress.

INTRODUCTION

The lands in southeast Arizona were isolated and among the last to be developed by American settlement. These were the lands of the fierce Apache tribes. After the death of Cochise in 1874, there was no clear succession of leadership. This made the Apache more rapacious and created severe hazards for any settlers who entered the area.

Because of this, when Ed Schieffelin decided to prospect in the San Pedro Valley in 1877, he used Brunckow’s Cabin as a base of operations to survey the country. After many months, while working the hills east of the San Pedro River, he found pieces of silver ore in a dry wash on a high plateau called Goose Flats. It took him several more months to locate the source. When he found the vein, he estimated it to be fifty feet long and twelve inches wide. Schieffelin’s legal mining claim was sited near Scott Lenox’s grave site, and on September 21, 1877, Schieffelin filed his first claim and logically named his stake Tombstone. The name came to mean much more for those notorious and nameless who died there and are laid in Boot Hill.

When the first claims were filed, the initial settlement of tents and wooden shacks was located at Watervale, near the Lucky Cuss mine, with a population of about one hundred. Schieffelin, his brother Al and Richard Gird, their mining engineer partner, eventually brought in two significant strikes, the Toughnut and the Lucky Cuss. Schieffelin also owned a piece of Hank Williams and John Oliver’s Grand Central, which they called the Contention. The San Pedro Valley quickly became a mining bonanza.

Storefront on West Allen Street, 1933. Library of Congress.

Ironically, hard-rock mining was the antithesis of the American western dream, for the minerals required substantial capital and company organization to get the ore out. Former territorial governor Anson P.K. Safford offered to find the financial backing for a cut of the strike, and so the Tombstone Mining and Milling Company was formed to build a stamping mill. While the mill was undergoing construction, U.S. Deputy Mineral Surveyor Solon M. Allis finished surveying the site of the new town, which was made public on March 5, 1879. The tents and shacks near the Lucky Cuss were moved to the new town site on Goose Flats, a mesa above the Toughnut Mine broad enough to hold a growing town. Lots were sold on Allen Street for five dollars each. The town rapidly had some forty cabins and just over one hundred residents. At the town’s founding in March 1879, it took its name from Schieffelin’s first mining claim. By fall 1879, several thousand souls were living in a canvas and matchstick camp perched above the richest silver strike in the Arizona Territory.

Like all mining towns, Tombstone grew like a mushroom. The mill and mines were continuously running with three shifts; union wages paid $4 a day, and the mostly young, single men needed some place to roar. Allen Street provided it. Nearly 110 locations were licensed to sell liquor, and most sold other things as well. The hotels, saloons, gambling dens, dance halls and brothels were open twenty-four hours a day. By 1881, the population had reached 6,000. At the height of the town’s growth in 1885, the community was near 10,000, making it the largest city in the territory. By 1884, the miners had taken $25 million in silver out of the ground. The most considerable difficulty facing the miners was obtaining water. Until 1881, it had to be hauled in. Eventually, the Huachuca Water Company created a pipeline that funneled water twenty-three miles from the Huachuca Mountains.

The rough part of town was situated along Allen Street. All around it, respectable people were struggling to earn a living and establish civilization as they had done elsewhere in the West. Four churches catered to different denominations (Catholic, Episcopalian, Presbyterian and Methodist), and there were two newspapers (the Nugget and the Epitaph), schools, lodges and lending libraries. Schieffelin Hall, a large, two-story adobe building, provided a stage for plays, operas, revues and all the respectable stage shows. The Bird Cage on Allen Street provided the stage for the disreputable ones.

The town developed a split personality. On the one hand, decent, God- fearing folk trying to make a fair life for their families; on the other existed the flashy, commercial town full of soiled doves and tinhorn gamblers who catered to the wants and desires of the miners and cowhands. In the back of the demimonde lurked a criminal organization that would take a presidential proclamation and the threat of martial law to dislodge. There was also a fundamental conflict over resources and land; traditional, southern-style “small government” agrarianism of the rural cowboys contrasted with northern-style industrial capitalism.

Ruins of commercial buildings on Fremont Street, 1933. Library of Congress.

In the beginning, Tombstone was part of Pima County, whose seat was in Tucson, many hard miles away. Even farther away was Prescott, the territorial capital. The territory was run by the Democrats, who, in those days, were surprisingly corrupt. In 1881, the southeast corner of Pima County was divided to create Cochise County—with its seat in Tombstone—and the situation in the newly formed county was difficult. Not only were hard cases drawn there by the presence of silver, but the town also was located close enough to the Mexican border to become the center of an extensive trade in stolen cattle.

The head of the Cowboy rustlers was N.H. (Old Man) Clanton. He owned a ranch of sorts near Lewis Springs. The Sulphur Springs Valley was the site of another cattle rustling group, the McLaury brothers. The two groups controlled the water holes for miles around. What cattle they did not run up from Mexico, they lifted from their neighbors. Their hired help and comrades were the likes of Curly Bill Brocius and Johnny Ringo, and only the strongest could hold out against them.

In the summer of 1879, the first ore shipments came out of the mill, and by the fall, the first Wells Fargo stagecoach robbery had occurred.

The Cowboys struck and retired to their ranches, untouchable because they were protected by the corrupt Cochise County sheriff, John Behan. Very few of the Cowboys were ever arrested, even when they had been recognized, and those few unaccountably escaped custody. Old Man Clanton died in 1881, murdered in retaliation for a cattle raid into Mexico, and his place as the gang’s leader was taken by Curly Bill Brocius, who had killed Tom White, Tombstone’s first town marshal.

Soon, the Cowboys were determined to dominate Tombstone as they did the surrounding countryside. Between them and their objective stood two men: U.S. Deputy Marshal Wyatt Earp and his brother Virgil, the town marshal. Many of the town’s honest people banded into a vigilante group called the Citizens Committee of Safety and backed the play of the Earps.

Political and economic factors also brought about the enmity between the two groups. Personal hatred is what brought on the gunfight. On October 25, 1881, Ike Clanton rode into town and got incredibly drunk. He then went from bar to bar, openly threatening to kill the Earps and their friend Doc Holliday. The following morning, he was joined by his brother Billy, Frank and Tom McLaury and Billy Claiborne. The tension in the air was thick, and the townsfolk were uneasy.

It was just after two o’clock in the afternoon when Wyatt, Virgil and Morgan Earp walked out of Hafford’s Saloon on the northeast corner of Fourth and Allen Streets to apprehend the Clantons and their comrades for violating the law against carrying firearms within the town limits. As they walked toward the O.K. Corral, they were joined by Doc Holliday, indignant at the thought that they might leave him behind.

The location of the trial of the Earps and Holliday for murder after the gunfight. Library of Congress.

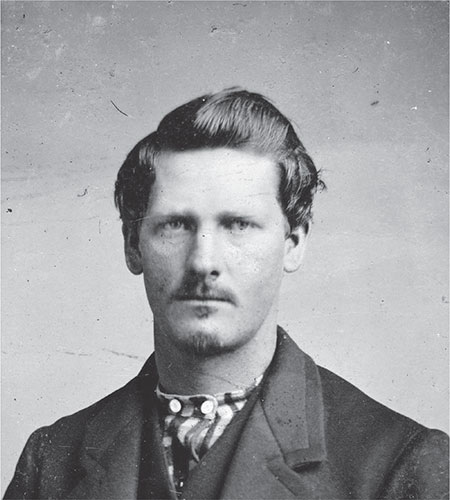

Wyatt Earp before he came to Tombstone. Wikimedia Commons.

The offices of the O.K. Corral were on Allen Street between Third and Fourth, but an empty lot ran through to Fremont Street toward the north. The Cowboys waited in in the open lot between Fly’s Photo Studio and the Harwood House. Sheriff Behan rushed to meet the lawmen midway and announced that he had disarmed the Cowboys. After finding that he had not arrested the men, the Earps and Holliday brushed him aside and continued down Fremont Street. As they passed Fly’s Studio, they turned left into the yard and confronted the five men. What happened next took only thirty seconds. Seventeen shots were fired on each side. When the smoke finally cleared, Frank and Tom McLaury and Billy Clanton were dead. Virgil and Morgan Earp were wounded, and Doc Holliday was grazed in the hip.

After the gunfight, the Earps moved their families to the Cosmopolitan Hotel for mutual support and protection. When Judge Wells Spicer exonerated the Earps and Holliday of murder, the Cowboys were infuriated and even more determined to get revenge. The reign of terror increased. Mayor John Clum, the editor of the Epitaph and a staunch supporter of the Earps, survived an assassination attempt by sheer luck and quick thinking. Murders on the streets of Tombstone and stagecoach robberies increased.

At about 11:30 p.m. on December 28, 1881, three men hid in an unfinished building on Allen Street across from the Crystal Palace Saloon. They ambushed Virgil Earp as he walked from the Oriental Saloon to his room. He was hit in the back and left arm by three loads of double-barreled buckshot. The Crystal Palace Saloon and the Eagle Brewery behind Virgil were struck by a total of nineteen shots. Three passed through the window, and another went about a foot over the heads of several men standing by a faro table.

Because Virgil’s arm was permanently crippled by the attack, another town marshal was appointed, and the Earp faction lost important official power because Wyatt’s jurisdiction as a U.S. marshal applied only to federal cases.

The Weekly Arizona Miner wrote about the repeated threats received by the Earps and others.

For some time, the Earps, Doc Holliday, Tom Fitch and others who upheld and defended the Earps in their late trial have received, almost daily, anonymous letters, warning them to leave town or suffer death, supposed to have been written by friends of the Clanton and McLowry [sic] boys, three of whom the Earps and Holliday killed and little attention was paid to them as they were believed to be idle boasts but the shooting of Virgil Earp last night shows that the men were in earnest.

The Los Angeles Herald reported on December 30 that the “Doctor says there are four chances in five that he [Virgil Earp] will die.” It stated that “Judge Spicer, Marshal Williams, Wyatt Earp, Rickabaugh, and others are in momentary danger of assassination.…The local authorities are doing nothing to capture the assassins so far as is known.”

After John C. Frémont, governor of the Arizona Territory, resigned, acting governor John J. Gosper swiftly moved against the lawlessness in Cochise County by appointing Wyatt Earp to drive out the outlaws. In retaliation, Sheriff Behan reopened the O.K. Corral case.

At 10:50 p.m. on Saturday, March 18, 1882, after returning from a musicale at Schieffelin Hall, Morgan Earp was ambushed. He was playing a late round of billiards at the Campbell and Hatch Billiard Parlor against owner Bob Hatch. Dan Tipton, Sherman McMaster and Wyatt watched, having received threats that same day.

The assailant shot Morgan through the upper half of a four-pane windowed door, as the bottom two window panes had been painted over. The door opened onto a dark alley that ran through the block between Allen and Fremont Streets. Morgan, who was about ten feet from the door, was struck on the right side, and the bullet shattered his spine, passed through his left side and entered the thigh of mining foreman George A.B. Berry. Another bullet lodged in the wall near the ceiling over Wyatt’s head. Several men rushed into the alley but found the shooter had fled.

After Morgan was shot, his brothers tried to help him stand, but Morgan said, “Don’t, I can’t stand it. This is the last game of pool I’ll ever play.” They moved him to the floor near the card room door. Dr. William Miller arrived first, followed by Drs. Matthews and George Goodfellow. They all examined Morgan. Goodfellow, recognized in the United States as the nation’s leading expert at treating abdominal gunshot wounds, concluded that Morgan’s injuries were fatal.

While Wyatt and the youngest brother, Warren, were escorting Virgil and his wife to Tucson, Wyatt shot and killed Frank Stilwell, one of the Cowboys. Because he knew the conditions in Tombstone, Sheriff Paul did not issue warrants for the Earps, but Sheriff Behan deputized Curly Bill Brocius and the other gunslingers of the Cowboy faction to arrest the Earps or shoot them on sight. The county, territory and eventually the nation were subjected to the spectacle of the federal posse and the county posse stalking each other across the Arizona desert—Wyatt with federal warrants for the arrest of the Cowboys and Behan with no legal justification at all.

Old City Hall, Fremont Street, 1933. Library of Congress.

After Wyatt killed Curly Bill at an ambush at Iron Springs, the remaining Cowboys fled to Mexico. The surviving Earps traveled north into Colorado.

The new territorial governor, F.A. Trittle, had just taken his post when the murder of Morgan Earp escalated matters. On investigation, he sent an urgent appeal to President Chester Arthur asking for funds to set up a regional police force to deal with the situation. Arthur did one better and requested aid in a special message to both houses of Congress on April 26, 1882. Congress suggested using the army instead. On May 3, Arthur’s Presidential Proclamation threatened martial law by May 15 unless the situation was rectified.

Governor Trittle and Pima County sheriff Paul told Governor Pitkin of Colorado that they could not guarantee the safety of the Earps, so Pitkin refused extradition. That was the end for the Earps. Wyatt followed the frontier wherever it went. Eventually, he retired in Los Angeles, where he died in bed in 1929. Over his long career, he was never wounded.

In July, Johnny Ringo—the last Cowboy outlaw leader—was killed near Turkey Creek. There were still plenty of criminals and dangerous men around, enough to make “Texas John” Slaughter’s career as Cochise County sheriff famous, but the reign of terror was over. With federal interest aroused, Sheriff Behan did not run for reelection. Instead, he became the assistant warden at the Yuma Territorial Prison. He was later promoted to superintendent.

Tombstone eventually settled down to respectable prosperity. Two fires (June 22, 1881, and May 25, 1882) wiped out most of the business district, but it was promptly rebuilt. The prosperous times continued until 1883. By 1884, the price of silver had led mine owners to attempt to reduce wages from $4.00 a day to $3.50. The union struck, and violence at the mines brought what outlawry had never brought—more troops from Fort Huachuca.

In 1886, water filled the mines, and despite several attempts to pump the water out, the mines were closed. Two-thirds of the population left the town shortly afterward. Two brief periods of prosperity occurred, one in 1890 and another in 1902, but they did not last long. In 1929, the county seat was moved to Bisbee, and Tombstone lost its last reason for existing. But the town proved too tough to die. It pulled itself together, began restoration and rebuilding and found a new life as a tourist attraction. In 1961, it was declared a National Monument.

This historic landmark illustrates much of the flavor and vitality of the Wild West. As one of its historians, John Myers, wrote, “The great thing about Tombstone was not that there was silver in the veins of the adjacent hills, but that life flowed hotly and strongly in the veins of the people.”