In breaking through the skin-color barrier in American politics, does Barack Hussein Obama bring with him a distinctive African American moral vision—does he somehow embody an alternative version of American history? Some say so. They anoint the ascendancy of President Obama with world-historic significance linked to his race: a black man, an African American, a son of Africa has risen to occupy the highest office in the land! Hallelujah!

At Obama’s first inauguration, the soaring close of the Reverend Joseph Lowery’s benediction had the new president smiling and applauding. This famed black preacher, and longtime leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference after Martin Luther King’s death, exalted the humble in America’s history—its minorities, black, brown, yellow, and red—and humbled the exalted. He dared to hope that “white will embrace what is right.”1 Joseph Lowery nearly stole the show on that day in January 2009, confirming for many the glow of a blessing on a new era. Now that President Obama has won re-election, the iconic character of his ascendancy has been given an official seal of approval by the American people. We are living, for better or worse, in the Age of Obama.

Have we, in fact, entered a new era? More pointedly, do the election and re-election of Barack Obama constitute some kind of fulfillment of Martin Luther King’s famous dream? I think the answer to this question must be a resounding “No!” Obama’s election has neither fulfilled King’s dream nor does it usher in any sort of new era.

In what follows I argue that the prophetic tradition of critical political thought and faith-based moral witness out of which the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. emerged, and which he embodied, is radically at odds with both President Obama’s electoral ambitions and his exercise of the powers of office. Neither is this tradition compatible with the president’s rhetoric concerning the moral significance of his ascendancy. For the tradition of social criticism that emerged over the generations from the suffering of the slaves, and that gathered strength from the unrequited hopes of the freedmen, has always and necessarily been keenly aware of the moral ambiguity of the exercise of American power in the world. No mere politician—not even one as gifted at oratory as Obama—can afford to give public voice to such critical skepticism about the American project. And yet, to achieve the historical rightness of national conduct for which King gave his life, it is essential to challenge publicly the prototypically American boast that this nation stands as a moral exemplar.

First, I want to acknowledge the truly historic nature of Obama’s election and the powerful hope for the possibilities for real change that he has brought to our nation. It is often said that the United States of America is a country defined not by kinship, ethnicity, religion, or tribal connection, but by ideas—ideas about freedom, democracy, and the self-evident truths that “all persons are created equal, and are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights,” to quote from Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence.

Another plain fact, too often forgotten, is that America is, always has been, and always will be a nation of immigrants. So, in November 2008 this nation of immigrants elected a son of Africa—a black man whose father was born in Kenya and who goes by the name Barack Hussein Obama—to be our forty-fourth president. “Historic” hardly begins to describe just how momentous, how remarkable, and how improbable is President Obama’s achievement. From now on, whenever Europeans complain to me about the flaws of American society—and there are many—I can respond by saying, “No, America is not perfect. But, please, can you show me your black president (or prime minister)?!”

As a black man who grew to maturity on the South Side of Chicago in the 1960s and who was inspired by the words and deeds of King, I could not help but feel a sense of personal joy at Obama’s triumph. Something profound has happened in America, of this there can be no doubt. Also, I will confess something: I was one of those cynics who didn’t believe it possible—who thought the “audacity of hope” was just an empty phrase. Even as I witnessed millions of believers rallying around this cause, even as I saw people of all races bending themselves to this historic task, even as I observed the vast increase in voter registration in African American communities and among the young all across the land—I nevertheless remained doubtful. It did not seem possible to me that the deep structure of American power would permit the ascent of this son of Africa and America to its pinnacle. But, I was wrong, thank God.

So, notwithstanding the somewhat caustic nature of what I argue in this essay, I celebrate the fact that America has twice elected this eloquent and brilliant young black man, this representative of the Chicago neighborhoods that I have known so well, this usurper of power from a complacent establishment, this proponent of “change,” as president of the United States of America. Whenever I reflect on this fact, I just want to shout, “Hallelujah!”

Nevertheless, I worry about what Obama’s personal success could imply for the future of the black prophetic tradition. Moreover, I am skeptical about the claims of this president of the United States—who happens to be an African American—to a connection with that tradition. I speak here not about his personal views, as a black man and/or as a Christian believer, but rather about his role as the occupant of a very special, very powerful office, with all of the awesome responsibilities which that entails. I rather doubt that these are commensurate matters at all—the black prophetic tradition on the one hand, and the exercise of executive power on the other. I doubt that they are denominated in the same units of currency, so to speak. That is, I doubt whether the black prophetic tradition has much to do with the exercise of the powers of the office of the presidency.

What do I mean by “the black prophetic tradition”? And, how does Obama’s ascendancy “fracture” it? To see what I am getting at here, consider the following quotations from two speeches, one given by King in 1967 and the other by Obama in 2009.

First, here is Obama in Oslo accepting the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize:

We must begin by acknowledging the hard truth: We will not eradicate violent conflict in our lifetimes. There will be times when nations—acting individually or in concert—will find the use of force not only necessary but morally justified. I make this statement mindful of what Martin Luther King Jr. said in this same ceremony years ago: “Violence never brings permanent peace. It solves no social problem: it merely creates new and more complicated ones.” As someone who stands here as a direct consequence of Dr. King’s life work, I am living testimony to the moral force of non-violence. I know there’s nothing weak, nothing passive, nothing naïve, in the creed and lives of Gandhi and King.

But as a head of state sworn to protect and defend my nation, I cannot be guided by their examples alone. I face the world as it is, and cannot stand idle in the face of threats to the American people. For make no mistake: Evil does exist in the world. . . . To say that force may sometimes be necessary is not a call to cynicism—it is a recognition of history; the imperfections of man and the limits of reason. . . . But the world must remember that it was not simply international institutions—not just treaties and declarations—that brought stability to a post–World War II world. Whatever mistakes we have made, the plain fact is this: The United States of America has helped underwrite global security for more than six decades with the blood of our citizens and the strength of our arms.2

By contrast, here is King denouncing the Vietnam War at Riverside Church in New York City on April 4, 1967:

As if the weight of such a commitment to the life and health of America were not enough, another burden of responsibility was placed upon me in 1964. And I cannot forget that the Nobel Prize for Peace was also a commission, a commission to work harder than I had ever worked before for the brotherhood of man. This is a calling that takes me beyond national allegiances. But even if it were not present, I would yet have to live with the meaning of my commitment to the ministry of Jesus Christ. To me, the relationship of this ministry to the making of peace is so obvious that I sometimes marvel at those who ask me why I am speaking against the war. Could it be that they do not know that the Good News was meant for all men—for communist and capitalist, for their children and ours, for black and for white, for revolutionary and conservative? Have they forgotten that my ministry is in obedience to the one who loved his enemies so fully that he died for them? What then can I say to the Vietcong or to Castro or to Mao as a faithful minister of this one? Can I threaten them with death or must I not share with them my life? . . .

This I believe to be the privilege and the burden of all of us who deem ourselves bound by allegiances and loyalties which are broader and deeper than nationalism and which go beyond our nation’s self-defined goals and positions. We are called to speak for the weak, for the voiceless, for the victims of our nation, for those it calls “enemy,” for no document from human hands can make these humans any less our brothers.3

So, here we can see the two greatest African American leaders of the past half century as they address themselves to the gravest public question of our time—that of war and peace. My, what a difference forty years can make!

King is a black American prophet standing squarely within the tradition of social criticism that I wish to defend here. Obama is not. This difference, I will argue, matters a great deal.

I see the black prophetic tradition as embodying an outsider’s and underdog’s critical view about the national narrative of the United States of America. It is, to be concrete, a historical counternarrative—one, for example, that sees the dispossession of the native people of North America as the great historic crime that it was; one that looks back on the bombing of Hiroshima with feelings of horror and national shame. It is an insistence that American democracy—which of course has always been a complicated political compact, often serving the interests of the powerful at the expense of the weak—live up to the true meaning of our espoused civic creed. It is an understanding that struggle, resistance, and protest are the only ways to bring this about. And it is the recognition that even in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century, America has yet to fully do so.

The black prophetic tradition is antitriumphalist vis-à-vis America’s role in the world, and it is deeply suspicious of the “city on a hill” rhetoric of self-congratulation to which American politicians, including President Obama, are so often inclined. It is a doggedly critical assessment of what Americans do, an assessment that sympathizes in a deep way with the struggles of those who are dispossessed: the stateless Palestinians in the Middle East today, for instance, or the blacks at the southern tip of Africa three decades ago. This is a tradition of moral witness within American historical experience that I associate with the antislavery movement of the nineteenth century and the civil rights movement of the twentieth century. It is a tradition that views “collateral damage”—where civilians are killed by U.S. military operations—as not simply the unavoidable cost of doing the business of national defense in the modern world, but rather as a deeply problematic offense against a righteousness toward which we ought to aspire. What I am calling the black prophetic tradition also reflects a universal theory of freedom—one with a strong antiimperialist, antiracist, and antimilitarist tilt.

What, then, is President Obama’s relationship to this tradition? What, in this regard, are we entitled to expect from him? I have concluded that as president his connection to this great moral tradition is tenuous, at best. More crucially, we would be foolish to expect much at all from him in this vein. President of the United States is an office. The office has its own imperatives quite apart from an individual’s personal beliefs. When one is sitting with military advisers and is told that a Predator drone operation against a “terrorist” operative in the tribal regions of Pakistan awaits one’s authorization, then one has to make that call. Such a moment as that is no time to be quoting Martin Luther King or Frederick Douglass, or to be talking about the tradition of critical political thought which has been nurtured by black people in America for centuries.4 Rather, at a time like that, one simply has to decide whether or not one is going to kill that person. The person who is the commander in chief of the United States of America, regardless of his individual biography, when placed in that position and forced to carry out those acts, needs to be viewed with clear-eyed realism for who and what he is: namely, in the context of the example at hand, the commander in chief of the largest military force in the history of human experience. Such a person ought not to be viewed through a rose-tinted glass, with some romantic and unrealistic narrative.

So, the question I wish to pose is this: what does the tradition of black protest and struggle in America have to do with the exercise of the powers of the office of the presidency? I suspect that the answer to that question is, very little at all. Romantic idealists argue that surely his biography, his history, even his skin color informs the man who is now president. But that merely shifts the question to an inquiry about the extent that personality and individual morality can exert real leverage over the exercise of such an office as the American presidency.

Here is an analogy to ponder: a woman rises to the position of CEO at a large corporation—for instance, Exxon-Mobil or Bank of America. What real difference should we expect this to make—for matters like the environment, or economic equity, or corporate governance? At the end of the day that job is about making money for the shareholders. It is not about anything else. It is not about saving the planet, or integrating the workforce, or ending poverty. It is about making profits for the shareholders. Now this woman—with her unique experiences and inspiring biography—may approach the exercise of her responsibilities in that office with a slightly different style than would a man. But she will not be the chief executive officer for very long if she fails to continue making profits for the shareholders. The leverage she has for doing good in the world is small, relative to the imperative of sustaining her company’s financial performance at a high level.

Similarly, if someone is the chief executive officer and commander in chief of the largest military in the world—if someone has a military officer always nearby carrying a nuclear “football,” as the U.S. president does have, allowing one to signal the special codes to authorize the release of nuclear weapons so as to incinerate untold numbers of persons—then the imperative of that office is to “make profits for the shareholders.” The imperatives of office in the position of the American presidency are, essentially, to further the interest of the American imperial project, not to criticize that project. If one were to engage in too much of the latter, then one will not be running the show for very long. Yet, if the history of blacks in America teaches us anything, it is that the American imperial project must be criticized.

I am not attacking Barack Obama, the man. I admire him greatly. My assessment of Barack Hussein Obama, the man—given all I know about him, the books he’s written that I have read, the speeches he’s given that I have heard—is that he is compassionate and possessed of a deep historical sensibility. Left to his own devices, I feel confident in saying, he would always stand on the right side of history. King was fond of saying that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” In 2010, President Obama had a rug installed in the Oval office with King’s quote—one of Obama’s favorites—embossed upon it.5 It is at least arguable that the rise of Obama represents one way in which that moral arc is, indeed, bending toward justice. He is someone who has more room within his own philosophy for concern about the dispossessed than anyone who has held that office. He is, I believe, aware of the imperfections of American democracy and of the inflated character of some of the rhetoric that he himself has had to use as a matter of political expediency. But the office has its own imperatives. Those of us who have been clamoring for change, and who so far have been sorely disappointed, must take account of this plain fact.

Another crucial point to consider revolves around “the narrative,” and how the ascendancy of Obama to the presidency has affected our national discourse on issues of race and social justice. I recall that there was a heated discussion on this matter during the 2008 campaign, when candidate Obama gave his big speech on race—a speech made necessary by the uproar that had been created when some inflammatory comments of his former pastor, the Reverend Jeremiah Wright, came to public light.

The speech was very well received at the time, but I remember having been singularly unimpressed by it. “The best speech and the most important speech on race that we have heard as a nation since Martin Luther King’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech,” one gushing TV talking head pronounced, breathlessly.6 I recall thinking that a shocking degree of historical amnesia/ignorance had been revealed in the press commentary on Obama’s race speech. People were confusing personality with a kind of politics that would be capable of making institutional reforms. As I listened to Obama’s speech, my thoughts turned not to MLK, but to LBJ—and I compared, unfavorably, Obama’s “race talk” with LBJ’s commencement address at Howard University in 1965. Unlike Obama, LBJ staked out a political position that has had consequences.7 This kind of stand-taking was the very last thing candidate Obama wanted to do, for obvious reasons of electoral survival. Still, I found, and still find, the contrast to be instructive.

LBJ’s position was that the people of the United States were obligated to undertake a massive expansion of social investment for the disadvantaged in American society, and that this obligation rested at least in part on the historical necessity that we act so as to reduce racial inequality in our country. What LBJ had to say on that late-spring afternoon forty-three years prior—about race, history, policy, and social obligation—has echoed down through the decades. Of course, nobody could have expected Obama to argue for a return of the Great Society. Still, I thought at the time of Obama’s Philadelphia race speech in the spring of 2008 that his views about race and American social obligation—whatever their merits—were not in the same league with LBJ’s, not even close.

This matters greatly, for there is tremendous social inequality along racial lines in the United States even today, and there remains a great need for effective political advocacy on behalf of more egalitarian and more humane policies. To see what I am getting after here, consider the following brief survey of the facts on the ground.

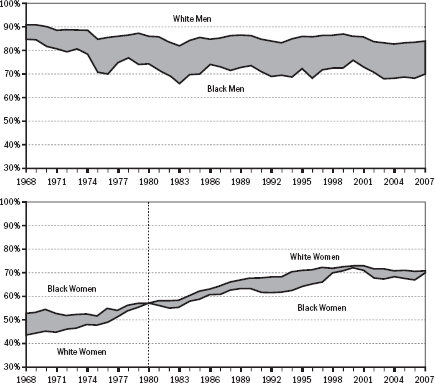

Percent of Native-Born Non-Hispanic Men and Women Aged 25 to 59 Who Were Employed from 1968 to 2007

Reynolds Farley, “The Kerner Commission Report Plus Four Decades: What Has Changed? What Has Not?” Population Studies Center Research Report No. 08-656, 2008.

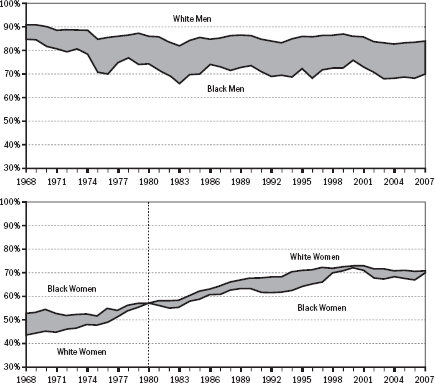

Percent of Native-Born Non-Hispanics Below the Poverty Line from 1968 to 2007

Reynolds Farley, “The Kerner Commission Report Plus Four Decades: What Has Changed? What Has Not?” Population Studies Center Research Report No. 08-656, 2008.

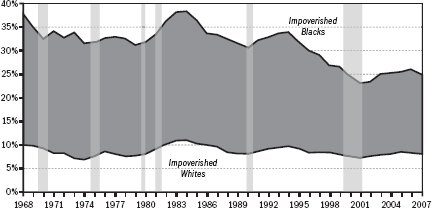

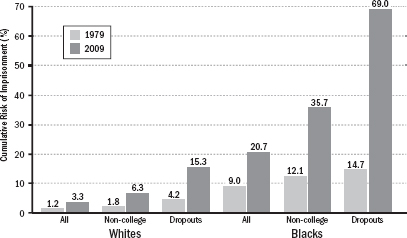

Men’s Risk of Imprisonment by Ages 30–34

Bruce Western, Punishment and Inequality in America (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2006).

I also came to think during his first campaign that this black presidential candidate, Barack Obama, did not really have the standing to renegotiate the implicit American racial contract on behalf of my (i.e., African American) people. What might that “implicit racial contract” be? Well, in a word, it is the broad recognition and acceptance by governing elites in this country—in the press, in the courts and legal establishment, in the academy, and in the broader political culture—that structural impediments exist to the equal participation of blacks in American life, and that government-sponsored initiatives (like affirmative action at public universities, but by no means limited to this) are an appropriate vehicle for redress in this situation.

It is the recognition that, despite the huge social transformation occurring in this society under the pressures of immigration, globalization, and rising economic insecurity—which are, as Obama has frequently pointed out, changes affecting all of us, regardless of race or ethnicity—we nevertheless have unfinished business here on the race front. It is the willingness to constantly interrogate our institutions as to whether their actual practices are consistent with our professed ideals concerning equality and social justice. It is an acknowledgment that, imperatives of personal and communal responsibility notwithstanding, the American nation-state nevertheless bears a collective, political responsibility for the social disasters and the human suffering that are unfolding, and that can be so readily observed in the centers of our cities.

This responsibility extends to immigrants who have joined our society in recent decades no less so than to those with American ancestry extending back many generations. Just as present generations—immigrants and natives alike—are obligated to service a national debt incurred by their predecessors, so too are those who prosper within our social order obligated to contribute to the fair resolution of social problems deeply rooted in the nation’s historical experience. This unfinished racial business, I would argue, is a part of what you inherit when you become an American.

While there has never been unanimity on these matters, there nevertheless has been a consensus view. This consensus has been under attack for a generation. And it is, in effect, being renegotiated by Obama as a consequence of his political ascendancy. I am not accusing Obama of being soft on affirmative action. Furthermore, some will object that Obama has shown through words and deeds his appreciation of the structural bases for racial inequality in this country. They will say that his views are nuanced, pragmatic, and historically well informed.8 This is all true, and I do not deny it. Still, the question that matters is not whether Obama knows anything about history or sociology. The question is, what are the American people prepared to do next, if anything, about these matters? And how will Obama’s vision promote progress?

Yet another key element to evaluate regarding the limits of reform and the importance of maintaining a sober realism when discussing the current American president, has to do with American foreign policy and, in particular, U.S. policies toward the conflict in the Middle East. When I have spoken in the United States about these matters, some people are perplexed by my evocation of the spirits of long-dead African American figures—practitioners of the black prophetic tradition—and by my connecting them with present-day moral concerns raised by the plight of the dispossessed, stateless Palestinians. How does this even come up, they seem to be asking, as if I pulled this subject out of thin air—as if it is somehow a real stretch to inject the conflicts of the Middle East into a discussion about race and American politics.

What I claim is that the moral legacy of these past, heroic warriors against white supremacy—the critical, subversive, prophetic, outsider’s voice that I associate with their legacy—stands in danger of being lost or, at least, severely attenuated. Obama’s “bargaining” with segments of the American people over such matters—as he strove to preserve his viability within the American political system in the midst of a presidential campaign and in the aftermath of his former pastor’s offending public remarks—could have the effect of counteracting this critical voice. Furthermore, one of the issues, among others to be sure, where this development could have practical consequences has to do with how the experience and political voice of blacks would be inflected within the ongoing, broader American national dialogue over the conflict in the Middle East. I stand by these claims.

For example, many may not remember how Louis Farrakhan became a nationally recognized figure. It occurred in the aftermath of Andrew Young’s resignation in 1979 from his position as Jimmy Carter’s U.N. ambassador, because Young had unauthorized contact with representatives of the Palestine Liberation Organization, contrary to official U.S. policy. Jesse Jackson had been forthright in defending Young and had traveled to Palestine to show solidarity with Young, and with Yasser Arafat. Five years later, during Jackson’s historic first run for the White House in 1984, a firestorm erupted after Jackson, in an unguarded moment of banter with reporters, referred to New York City as “Hymietown”—a remark by which many Jews, and others, were (rightly) offended. As Jackson fell under attack, Farrakhan spoke out before black audiences in Jackson’s defense, making a number of anti-Semitic remarks which were seen (again, rightly) as deeply offensive by many Americans.

Now, there is nothing new to the American experience about the notion that an ethnic group’s historically conditioned sensibilities might inform how members of that group come to construe, react to, and advocate about events taking place abroad—whether in South Africa, or Ireland, or Cuba, or Taiwan, or Palestine. I can say with some degree of certainty that Rev. Wright’s views—about the plight of the Palestinians and their victimization at the hands of what Wright has called U.S.-sponsored “state terrorism”—are not the least bit unusual, within the context of the black experience as lived, for instance, on Chicago’s South Side. That a person steeped in Wright’s social world could find himself reminded by events in today’s Middle East of the anticolonial and antiracist struggles of an earlier time can come as no surprise to anyone who has bothered to walk the streets of that community, to sit in its barber shops and beauty salons, or to spend more than a passing moment in the vicinity of a black church (or mosque) in the community that Obama represented in the Illinois state legislature for a decade. You can be sure that, no matter what he may say about the matter, these views were no revelation to Obama himself.

Take a look at what Obama actually had to say about this matter in his Philadelphia race speech on March 18, 2008:

But the remarks that have caused this recent firestorm . . . expressed a profoundly distorted view of this country—a view that sees white racism as endemic, and that elevates what is wrong with America above all that we know is right with America; a view that sees the conflicts in the Middle East as rooted primarily in the actions of stalwart allies like Israel, instead of emanating from the perverse and hateful ideologies of radical Islam.9

Again, I have to insist: the fact that a black Muslim or, for that matter, a black Christian religious leader, ministering to a huge flock in Chicago’s black ghetto, would fail to see the Palestinian-Israeli conflict as being due to a purportedly “perverse and hateful” Muslim ideology hardly certifies that said religious leader has a “profoundly distorted view of this country.” Such a claim is just propaganda, pure and simple, and it can serve only one purpose—to delegitimate criticism of American foreign policy by means of some not-so-sophisticated name-calling. One may agree or disagree with Wright’s (and, for that matter, Farrakhan’s) reading of the situation in the Middle East, but one cannot fairly characterize those views as deluded, unfounded, irrational, or un-American. In the sentence quoted above, acting on behalf of his own ambitions (and perhaps articulating sincerely held views), Obama nevertheless denied any space within the legitimate American conversation for an important dimension of the historically grounded, authentic African American political voice. In my considered opinion, he has not earned the right to do so.

I will conclude with a story about a friend of mine, Tony Campbell. The Reverend Anthony C. Campbell served as minister in the Boston University chapel during the summers for over a decade, until his death a few years ago. An African American who had for many years been pastor of a large church in Detroit, and who was a close personal friend of then B.U. president John Silber, Tony preached in the university’s chapel nearly every Sunday during the summers, while serving as preacher-in-residence and professor of preaching in the university’s school of theology. His sermons were broadcast throughout the New England region on the university-sponsored public radio stations.

As it happens, Tony’s father had also been a well-known Baptist minister. The family hailed from South Carolina, and Tony had an academic bent. Though a Baptist by birth, he was also very familiar with the Anglican and Episcopalian traditions. He had preached at Westminster Abbey and Canterbury. Indeed, before his death he preached sermons from pulpits in a dozen countries throughout the world. He was an elegant, beautifully poetic preacher. No ranting and stomping in the pulpit from him. He was always understated. His voice tended to get lower, and slower, as his sermons approached their climax. My son and I once traveled to New York from Boston for the sole purpose of hearing Tony preach at the Riverside Church, because it was such an honorific thing for him. On that occasion he once again hit it out of the park with achingly beautiful and profound reflections on Christian teaching.

Less than two weeks after the events of 9/11, Tony preached his final sermon of the summer at Boston University. I was there. The title he gave for that sermon was “A Reversal of Fortune.” His text was based on a teaching in the New Testament about the figure of Lazarus, not the one who was raised from the dead, but the wealthy man who ignored the beggars sitting in front of his door throughout his blessed life. When he died, said Lazarus was sent to roast in the fires of hell and upon asking for relief from the angel of the Lord was denied it, being told that he had had his chance on earth. When he asked that word be sent back to his brothers, lest they fall into the same condition, he was told, in effect: “They didn’t listen to Moses and the prophets, why would they listen now? Let them roast along with you.”

The late Reverend Anthony C. Campbell, heir to a great tradition of prophetic black preaching—an urbane, mild-mannered sophisticate—started his sermon with that scripture. This is a man who did not have a radical bone in his body—a Baptist with high-church pretensions who had preached at Canterbury. He was as thoroughly American and as committed a Christian as one could imagine. And he argued, in the wake of our country having been attacked by terrorists, that the United States was now in the position of the Lazarus figure of that biblical tale. We were, in effect and to some degree, he argued, reaping what we had sown. Those were not his words, of course. He was far too eloquent and subtle a preacher for that. But that was his message, and there really could be no mistake about it. He argued that we live now with the consequences of our neglect of complaints against injustice, our contempt for decent world opinion, our arrogance, our haughtiness, and our self-absorption.

The point of this extended closing anecdote is to explain and defend my assertion that the African American spiritual witness—for Christians, the teachings of the Gospel of Jesus Christ as refracted through the long generations of pain and suffering and disappointment and hopelessness endured by millions of the descendants of slaves in this country—has a prophetic message for the American people. In my humble opinion, Barack Obama has not earned the right to interpret that message to suit his political needs of the moment. More important, he certainly ought not to be allowed to denigrate or to marginalize it. With respect to the application of this tradition to moral problems raised by the plight of the Palestinians, this is precisely what he did during his campaign for the presidency.

As I ponder these questions, I am reminded of the work of the African American political scientist Martin Kilson, who is professor emeritus of government at Harvard and was a tenured professor at Harvard in the late 1960s and early 70s when student protest caused the university to establish a department of African American studies. Marty Kilson was a critic of that advocacy. He believed that African Americans needed to advance through the disciplines, coming up and earning their spurs just like anybody else. He didn’t want a separate department. But his thinking evolved. There is a book that he has been promising to write for years that was subtitled Neither Insiders Nor Outsiders. African Americans were neither insiders nor outsiders. Not insiders for the obvious reasons. Our noses are effectively pressed against the candy-store window. We do not quite have equal opportunity. But neither are we outsiders, because we are an indigenous American population going back six, eight, ten generations—sons of the soil, as American as anybody could possibly be. So, therein lies the conundrum, the paradox—neither insiders nor outsiders.

The central theme of American racial politics over the past quarter century is that outsiders are becoming insiders. Thus, the question arises: just what kind of insiders are we going to be? That, indeed, is the question. President Obama has given us one kind of answer. I wonder, is this the only one available to us?