Along with millions of others, I spent exorbitant amounts of time considering, analyzing, fretting, and exulting over the two presidential campaigns of Barack Obama and the difficulties he has encountered during his time in office. Obama is one of the most visible emblems of black masculinity we have before us today in the mainstream U.S. media. As a close reader of texts of various kinds, and as one with particular interest in African American iconography, I apply those tools of analysis to thinking about Obama in terms of symbols and symbolic power. The American president is the monarch in the following sense: he gives us an immediately available symbol, every single day, of who he is and thus who we (the body politic) are and might be. Let’s accept, for the sake of argument, that symbols actually do bear power. We have no imagistic precedent for understanding what it means for an Obama to be president and for Michelle Obama to be First Lady. What is instantly rewritten when a black woman is for the first time at the highest levels of our nation’s imaginary, at the head of the category of “lady”? Policies, appointments, and issues are all of obvious import. But my analytic focus is on how Obama means, which I hope is also an avenue to think about the immeasurable impact he has had on so many communities and how he helps us imagine what I call “free black men.”

What do I mean by “free black men”? My father is a free black man, and once you have been inculcated in that worldview there is no acceptable alternative. There have been free black men as long as there has been American history, from nineteenth-century exemplars, such as Frederick Douglass, David Walker, Nat Turner, and Joseph Cinqué, who were “free” when they were not literally free, to the twentieth-century likes of W.E.B DuBois, Marcus Garvey, Martin Luther King Jr., Ossie Davis, A. Philip Randolph, and Malcolm X, black men whose superbad words and deeds operate according to a logic utterly outside of supplication. Even if we understand the ways racism and classism and sexism have clipped our wings and our tongues and our imaginations; even if we know the literal and metaphorical violence black men are up against on a daily basis; even if we recognize the straitjackets of stereotype and its consequences, we must also know black men who teach us how to think outside the proverbial box, even as they know how to delineate the parameters of the box, who can imagine what the poet Robert Hayden called “something patterned, wild, and free,” which is to say black selves beyond the reach of the pernicious roadblocks to our full and flourishing personhood.

I am always watching for free black men, in the public arena and up close, and I know them when I see them. I had a colleague once who would proclaim out loud, “This is BORING!” in his meetings with his all-white colleagues at an elite university talking infinitely about the supposed superiority of European culture. He didn’t meet their arguments with measured reasoning, with footnotes. He didn’t clench his jaw, clear his throat, sip from a lukewarm glass of water, and later implode. No, he rejected the terms of their assertions and gave them not one second of his own considerable intellectual energy. He merely dismissed them: This is BORING! He thrilled and empowered me beyond measure: this man had said the emperor had no clothes! How liberating to say, maybe they’re not that smart and maybe they’re not that fascinating. Like Muhammad Ali’s “I’m so pretty,” which signaled a global beauty writ large, meant to make black male beauty displace all the other kinds of overly vaunted beauties in the world.

During the 2008 primary season, efforts to substitute Obama’s actual history and body with stereotypical ones was textbook and predictable. Youthful, Afroed drug-dabbler; turbaned colored other; darkened and more “sinister” black man, à la O.J. Simpson on trial; Farrakhan-loving, arm-waving black radical preacher. But what is interesting is that none of those images really stuck; the comparisons ultimately seemed absurd in the face of Obama himself. We passed through either a moment of actual shift or an anomalous moment wherein the power of false images could not override the power of the thing itself.

In its primary endorsement of Hillary Rodham Clinton, the New York Times called Obama “incandescent if still undefined.”1 Incandescent: artificial light, as in incandescent lightbulb. Not the sunshine. Blinding. Magical, mystical, hoodoo, conjurer, evanescent, inconsequential, evaporative. An optical illusion. Literally, substanceless. Light. Lightweight. In the act of conjuration, a form of deception. Not to be trusted. Don’t believe your eyes. Don’t trust it. Incandescent also refers to something called “black body radiation”; in physics, a black body is an object that absorbs all light that falls on it. The light emitted by a black body may be incandescent—black body radiation. I riff on this word choice to surface both “magic negro” stereotypes that floated around candidate Obama, and also the way he confounded those who beheld him with such wonder. This type of imagery was muted during Obama’s second presidential campaign but it lay just below the surface.

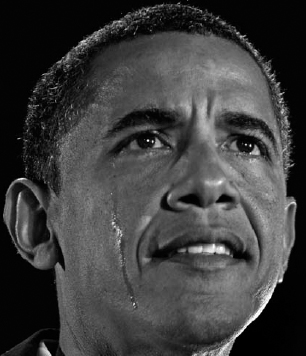

How do iconographically unprecedented representations of black men suggest something new underfoot in the present? The images of John Lewis, Andrew Young, and Jesse Jackson at the groundbreaking for the King memorial on the Mall are something we have rarely seen, grown black men weeping in public, holding each other’s bodies up as they weep. And why did they weep? There are so many potential answers, many things true at once. In the intense last year of the first Obama presidential campaign we saw Obama’s friend Marty Nesbitt listening to Obama’s so-called race speech in Philadelphia; Obama himself, crying at the end of almost his final campaign appearance after speaking of the death of his grandmother on the eve of the election; and then, Jesse Jackson in Grant Park after Obama had been named president—once again, so many unknowable feelings behind those tears.2 These men cry at moments of extraordinary progress, but their expression of “we’ve come so far” is not merely celebratory; it must hold simultaneous with triumph a memory of struggle and travail. They cry, it seems to me, for Gordon the slave who did not, and for the Medgar Everses and Fred Hamptons and Martin Luther Kings who gave their lives along the road to something hopefully better.

The Reverend Jesse Jackson comforts former UN ambassador Andrew Young during the groundbreaking for the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial in Washington, D.C., on November 13, 2006. Lawrence Jackson/AP

Andrew Young speaks about the significance of the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. Also present is Georgia representative John Lewis (leaning on shovel). Lauren Victoria Burke/AP

Tears flow down the face of supporter Marty Nesbitt as Democratic presidential hopeful Senator Barack Obama speaks about race during a news conference in Philadelphia on March 18, 2008. Alex Brandon/AP

Democratic presidential nominee Senator Barack Obama cries while speaking about his grandmother during a rally at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte, on November 3, 2008. Joe Raedle/Getty

Gordon, a freed slave in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, displays his whip-scarred back in 1863. Corbis

The Reverend Jesse Jackson reacts after projections show that Senator Barack Obama will be elected to serve as the next president of the United States during an election night gathering in Grant Park in Chicago on November 4, 2008. Joe Raedle/Getty

Derrick Bell, free black man. Harry Belafonte, free black man. Amiri Baraka, free black man, not only because he is a born genius, but also because he adapted contentious critique as his mode in his poetics and in his public utterance. Even when he is wrong, he is free. Free black men who are loud, free black men who are quiet. The brother I see kissing his son goodbye every morning at school, those kisses standing out from the other black fathers I see, free black man. Most black jazz musicians, listening for their own strange, unprecedented, and historical selves in the sometimes powerfully nonrepresentational musical language—resisting the straitjackets of representation—and offering it to us. I invite you to imagine the free black men in your communities. It is an enlightening exercise.

Free black men. Among some of the things my father taught me: always carry “F-you money” and keep some in the bank, no matter what, so that you have your own money on you, so you can always walk away from the man, the job, the situation—that you had to put yourself in. A situation where lack of funds would not cost you your life, your health, your dignity. This philosophy went beyond the dime for the emergency phone call, and it wasn’t about the amount of money. The point was that no white man’s job was worth your mental health. Period. He instructed me to always speak up for what you knew was right, even when absolutely no one in the room would sign on with you, because you never knew who would be listening, and someone was always listening. He taught me to ignore fools, simply ignore them, call them fools, reject their paradigms and render them irrelevant, even if they had power over my very livelihood. This is not always practical advice but it is soul saving. Even when you don’t act according to those dicta, to have them in your arsenal is crucial and enabling. Seeing yourself relative to the always-dominant paradigm is a soul-killing game; my father taught me that if we evaluated black people in terms of those paradigms, we would forever come up short and supplicating.

He saw his mother work, like most black men. Her name was Edith McAllister Alexander. She was a righteous warrior who taught him things like memorizing badge numbers of Harlem police officers in the 1930s and 40s and then reporting them for their abuses against black children. This abuse of authority first happened for my father when he was eight. She organized a successful campaign against New York City newspapers to get them to stop identifying only black alleged criminals by their race. His own father was a quieter man who taught my father much about kindness and decency, diligence and honor. But I am quite sure it was his mother who taught him how to fight and who made him free; I extend this argument to say, free black men cannot exist without black feminists. Free in this context doesn’t just mean having accomplished the seemingly impossible. It doesn’t just mean being outspoken. It means, to borrow from Langston Hughes, being “free within ourselves,” but in a way which is discernable to and legible by those in his community. “You never know who is watching you when you stand up, even if nobody tells you they support you.”

Is Barack Obama a free black man? When he refuses to hew to party lines about black and white, when he is cool in the face of month after month of racial bait, as he articulates a nuanced identity without being cute about being “black” or “biracial,” when he respects his listeners by presenting ideas in the best language he has, understanding that words are what we live in and they have true power, and when he displays his evident intelligence and cool dignity, I think he expands the mainstream imaginary under the sign of “African American man” and a free black manhood that does crucial, sometimes surreptitious work. During the 2008 primary season, when pundits repeatedly called for Obama to get angry, to fight back against the Clinton campaign’s trickery, I thought of the battle royal scene in Ellison’s Invisible Man, and the protagonist’s subsequent discovery that the letter of introduction he’d taken with him to seek employment in fact read “Keep this nigger boy running.”

At a campaign rally in October, Obama pulled a clever one by using the words “hoodwinked” and “bamboozled” to a mostly black audience from which he knew he’d get an amen. He slyly conjured Malcolm X, without having to actually become visibly angry or “radical.” His words alluded to Spike Lee’s film Malcolm X (“You’ve been had. You’ve been took. You’ve been hoodwinked. Bamboozled. Led astray. Run amok.”), which is perhaps even more media savvy than quoting Malcolm himself. And indeed, when the literally, visibly angry black man was before us as an Obama surrogate in the figure of the Reverend Dr. Jeremiah Wright, African-dress wearing and growling with passion in the same clips looped incessantly on television, that angry black male body became horrifying for the same liberal white commentators (Anderson Cooper, Chris Matthews) for whom Obama was their cool black roommate in college just a few days prior. “Anger” at American inequality is a tarring brush. That wish for a visible and discernable kind of ire was a wish for a spectacle. A black man with power engorged with the might of anger is a terrifying sight we have rarely seen in public. Middle-class black men who are in the public eye tend to experience a kind of implosive anger that has, as we know, taken its toll on their health in the disproportionate deaths from asthma, cardiovascular disease, and other ailments that kill not incrementally but rather cataclysmically (disproportionate rates of prostate cancer among black men being the exception to this point). And homicide. Or, rather, the increments are not visible, only the cataclysm. What would a brief flash of visible rage have done to the campaign? I see Obama’s cool not as masking rage but rather as an expression of profound discipline and an African philosophy of cool.

The success of the first Obama presidential campaign brought out the worst in mainstream white feminists. Gloria Steinem’s much-discussed op-ed in the New York Times (“Women Are Never Front-Runners,” January 8, 2008) essentially argued that in the race and gender hierarchical sweepstakes it was women’s (read: white women’s) turn to become president, implicitly before black men. Her strategic reminder to readers that black men got the vote before white women—as though that made them equal players in American society—echoes the deep rift in the white feminist movement that opened in the late 1860s. Outraged that black male suffrage could be accomplished without enfranchising women, vaunted white feminists such as Susan B. Anthony, Carrie Chapman Catt, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton affiliated themselves with white supremacy and made comments such as Anthony’s: “If intelligence, justice, and morality are to have precedence in the Government, let the question of the woman be brought up first and that of the Negro last.” Stanton said, “As the celestial gates to civil rights is slowly moving its hinges, it becomes a serious question whether we had better stand aside and see ‘Sambo’ walk in the kingdom first.” Nearly fifty years later, Catt stated plainly, “White supremacy will be strengthened, not weakened, by women’s suffrage.”

During that presidential primary season, former vice presidential candidate Geraldine Ferraro repeatedly stated, “If Obama was a white man, he would not be in this position. And if he was a woman of any color, he would not be in this position. He happens to be very lucky to be who he is. And the country is caught up in the concept.”3

Black women are nowhere in these pictures, either in the vision of female electoral power that mainstream white feminists envisioned in 1868 or in 2008. That they cannot imagine a black male candidate as being in their best interest overextends the idea that we should vote for people “who look like us.” Obama, by the way, never made any kind of gender-based critique of Clinton. If someone had asked him, “How do we beat the bitch?”—which was asked of John McCain during the campaign in reference to Hillary Clinton by a very blonde, older woman in a headband, pearls, and an accent sometimes described as “Locust Valley lockjaw”—Obama certainly would have responded quite differently from McCain, who laughed a little nervously and then said, “That’s an excellent question.”4 Obama came of age in family contexts where the full participation of women was a given, so much a given as to be unworthy of extended comment. This is something else that separates him from previous generations of black male leadership and also undergirds the liberation of mind that would characterize a free black man. “It’s our turn,” white feminists intoned during the primaries, implicitly, explicitly, and with increasing bitterness, as though no allegiance can ever be made across race or gender, as though “I” is the most important unit of thought, as though tit for tat is the way to make things right, as though black women do not exist. That belief system is the cancerous center of what’s wrong with that kind of feminism.

Even privileged black feminism is not tit-for-tat feminism. I think of Elsa Barkley-Brown’s essay “Negotiating and Transforming the Public Sphere: African American Political Life in the Transition from Slavery to Freedom,” which describes African American men’s votes as being the joint or family vote, decided on together, with many black women accompanying their husbands to the voting booth with shotguns hidden in their aprons.5 That kind of we are not playing pragmatism is a hallmark of black feminism, understanding as we do that we must navigate and negotiate the realities of disenfranchisement and partial emancipation, and most important, that our fates as black men and women are intertwined.

And what do free black men owe to black feminism? If Obama can be a free black man, it is at least in part because of the black woman he is married to, who gives forty-five-minute speeches without notes and without smiling, telling us things like “Power is hard,” “Never give up your power,” “You have to fight for your power every single day,” “Change is hard. It will always be hard. And it doesn’t happen from the top down,” and so forth. Her persona is tough, demanding, and pragmatic. And she says “black things,” with a very savvy understanding of what might not be so successful coming from him.

When Barack and Michelle Obama first appeared on 60 Minutes in a dual interview, their performance was a model of what a free black manhood intertwined with black feminism might look like.6 You saw their proximity, their overlapping heads, the way her words seem almost literally to emanate from his, but his mouth is closed. Her surrogacy was made almost explicit with the glance they gave each other before she answered questions, and then after, with his wry smile of both assent—endorsing the truth of the message, and the identity it confers upon him—as well as endorsement of his forthright wife speaking in the familiar truth-telling directness that is a particular rhetorical hallmark of black women. She closes the fused circle of the two-as-one when she says, “We just weren’t raised like that,” their dual upbringings now one. In many speeches she performs a similar rhetorical strategy when she moves from “people” to “a man like Barack Obama,” the singular “I” in service to the communal “we.”

Black feminism, in the form of Michelle Obama, took black Americans through their own skepticisms about her husband. Remember, at the beginning of his first presidential campaign he did not enjoy the level of black support he now has. The conversation about “Is he black enough?” though I think manufactured by white people, was nonetheless relevant. Michelle Obama repeated her story of first encounter with her husband-to-be: “I’ve got nothing in common with this guy. He grew up in Hawaii! Who grows up in Hawaii? He was biracial. I was like, okay, what’s that about? And then it’s a funny name, Barack Obama. Who names their child Barack Obama?”7 She acts as the surrogate chorus for so many black people, working us out of our racial and class litmus testing.

She was called “emasculating” by Maureen Dowd and many others.8 I don’t want to reprise all of the ways in which Michelle Obama was painted as the stereotypical “angry black woman.” Conservative websites abounded with “angry Michelle” photographs; mainstream internet comments vibrated with the viral throb of racist and sexist invective, such as Fox News’s Bill O’Reilly’s response to a caller who claimed she knew Michelle Obama to be “angry” and “militant” with, “I don’t want to go on a lynching party against Michelle Obama unless there’s evidence, hard facts, that say this is how the woman really feels. If that’s how she really feels—that America is a bad country or a flawed nation, whatever—then that’s legit. We’ll track it down.”9 That still hasn’t received the kind of attention it should have, showing the ways in which the safety of black women is often overlooked or subsumed under the idea that we are so “strong” that we don’t need defense or protection, let alone a pedestal. This is just some of the thinking that Mrs. Obama as First Lady has pushed back against.

“Angry Michelle” to me is the black women going to the polls with their men with shotguns in their aprons. Michelle Obama showed us black families, where the woman has never been on a pedestal nor has the man, where we eschew the kind of tit-for-tat heterosexual feminism that my black sisters and I decry in our equally privileged white sisters. She can say Barack didn’t put the butter away or Barack didn’t pick up his socks because we understand the bigger picture. Just like we understood before we had the vote that the black man’s vote was the precious family vote, so too we understand that our struggles are greater than butter and socks. Here is another quotation, from a campaign luncheon on April 16, 2007:

But the reality is that my husband is a man who understands my unique struggle and the challenges facing women and families. It is not just because he lives with me, someone who is very opinionated and makes my point. I am not a martyr so he hears it. It is because he actually listens to me and has the utmost respect for my perspective and my life experience. It is also because he was raised in a household of strong women who he saw struggle and sacrifice for him to achieve his dreams. He saw his grandmother, the primary breadwinner in their household, work her entire life to support their whole family. He saw his mother, a very young, very single-parent trying to finish her education and raise two children across two continents. He sees his sister, a single-parent trying to eke out a life for herself and her daughter on a salary that is much too small. He sees it in the eyes of women he meets throughout the country, women who have lost children and husbands in the war, women who don’t have access to adequate healthcare, to affordable daycare or jobs that pay a living wage. Their stories keep him up at night. Their stories, our stories, are the foundation of what guides Barack throughout his life. . . . But we need you to join us, because, you know what? Barack, as I tease, he’s a wonderful man, he’s a gifted man, but in the end, he is just a man. (laughter) He is an imperfect vessel and I love him dearly. (laughter and applause) In all seriousness, he is going to get tired. He is tired now. He is going to make mistakes. He will stumble. Trust me, he will say things that you will not agree with all the time. He will not be able to move you to tears with every word that he says. You know? (laughter) But that is why this campaign is so important, because it is not all about Barack Obama. It is about all of us. It is about us turning these possibilities into action.10

This is a kind of black feminist talk that feels resonantly cross-generational to me, stand-by-your-man rhetoric as told by black women: that love is fierce and demanding and often uncute and unsmiling; that even as they are protectors, black men also need to be protected by the women who love them; that all of us are vulnerable; that we only thrive collectively; that we can disagree and still be allied. Because black women have not occupied the pedestals of femininity; because black women have historically worked; because black women understand the many meanings of “pool your resources”; because conventional gender roles have already been deconstructed for us. There is liberatory space in these negations.

Free black manhood must articulate its visionary-ness as something that names the disproportionate burdens black women carry, that names the continued experiences of being the detail people, the cleanup women, not always seen or imagined as the leaders we are or can or should be. Black women have fathers and brothers and husbands and sons; black men have mothers and sisters and daughters and wives. Our fates are intertwined, and so must the strengths of our bodies of knowledge, ideologies, and wisdoms be intertwined. The candidate has become the president of the United States, and the question of how anyone can be free within the strictures and demands of the job on the world stage is one I am not equipped to answer.

John Hope Franklin and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, From Slavery to Freedom (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2010).

The great historian John Hope Franklin’s legacy and memory inspired this essay, so here I conclude with a read of the cover of the ninth and latest edition of his foundational African American history textbook, From Slavery to Freedom, prepared by Harvard professor and chair of African American studies, Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham.11 As the book came out, the publisher could not resist putting the first African American president on the cover. A color image of Obama faces a black-and-white image of the Negro bonded, visually marking the distance from the American past to the present, “from slavery to freedom.” The American flag is the background, its symbolic glory and possibility restored. The book that was written by a black scholar who did some of his early research inside a small room that segregated him from white researchers has moved from margin to center; the book is written from an African American studies department at Harvard University. A “triumphal” version of American history now dominates. African American history has been visually moved to the center, in the person of the first black president.

But what’s wrong with this picture? I resist thinking that we ever come to the triumphal end, nor should we desire it. So I take interest in the fact that Obama’s back is turned in this image and that his face cannot be seen, so symbolic freedom is still, in part, unknowable, or knowable only in pieces and through the slow work of two steps forward, one step back. We are not, as viewers of this book cover, given the satisfaction of smiling back at a perhaps smiling Obama, and the implacable faces he faces are not altered to respond to what they see, either. Their gaze is skeptical and direct, as though the historical Negro will not be charmed nor cheered by the triumphal present. That looking and attempting to see things as they really are with the unflinching critical eye is the way black people have strategized and survived. The will to the triumphal is understandable in African American studies, as it is among any people who have suffered more than their share of oppressions. But the lesson of African American studies is that the call to the triumphal is a siren song. And so I hope that the ways in which the humanities forwards the racial conversation in this country—thorny, difficult, unsettled—will direct us to think in terms of process rather than finish line, and will leave us ever more open to the complexities of America’s racial story.

Not so long ago the president began airstrikes against Libya in an attempt to avert massacres of the Libyan people led by the unpredictable dictator Muammar al-Gadhafi. More recently, in the case of massacres and violence in Syria, he hesitated. Faced with myriad impossible choices as president, Obama toggles daily between the devil and the deep blue sea. I persist in dearly wanting—perhaps reading into—Obama’s presence to be empowering for black people. “He’s a wartime president as far as I’m concerned,” said my father, a free black man who deeply loves and supports the president.

Can the first black president be a free black man?