CHAPTER 5

Verbal Section Overview

Composition of the Verbal Section

Pacing on the Verbal Section

How the Verbal Section Is Scored

Core Competencies on the Verbal Section

Introduction to Strategic Reading

COMPOSITION OF THE VERBAL SECTION

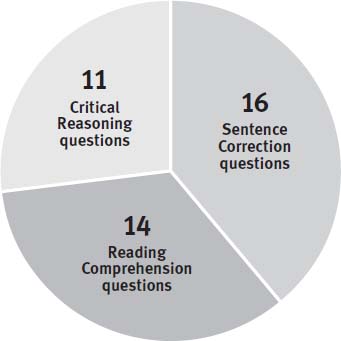

A little more than half of the multiple-choice questions that count toward your overall score appear in the Verbal section. You have 75 minutes to answer 41 Verbal questions in three formats: Reading Comprehension, Sentence Correction, and Critical Reasoning. These three types of questions are mingled throughout the Verbal section, so you never know what’s coming next. Here’s what you can expect to see:

The Approximate Mix of Questions on the GMAT Verbal Section: 11 Critical Reasoning Questions, 14 Reading Comprehension Questions, and 16 Sentence Correction Questions

You may see more of one question type and fewer of another. Don’t worry. It’s likely just a slight difference in the types of “experimental” questions you get.

In the next three chapters, you’ll learn strategies for each of these question types. But first, let’s look at some techniques for managing the Verbal section as a whole.

PACING ON THE VERBAL SECTION

The GMAT will give you four Reading Comprehension passages. Two will likely be longer and have four questions each, and two will likely be shorter and have three questions each. With less than two minutes per question on the Verbal section, where will you find the time to read those passages?

Part of the answer is that the Reading Comprehension chapter of this book will give you great tips about how to read the passages efficiently. Another big part, though, is how you will handle Sentence Correction. Follow the Kaplan Method for Sentence Correction, which you will see in the chapter devoted to that question type, and through practice you will bring your average time down to 60 seconds per Sentence Correction question. Moving through Sentence Correction questions quickly and efficiently will allow you the time you’ll need to read long Reading Comprehension passages and take apart complex arguments in Critical Reasoning.

Here are Kaplan’s timing recommendations for the Verbal section of the GMAT. While it’s far more important at first that you practice to build accuracy and mastery of the strategies, it’s also a good idea to keep these timing recommendations in mind. By incorporating more and more timed practice as you progress in your GMAT prep, you will grow comfortable with these timing guidelines, and following them will contribute greatly to your success on Test Day.

Verbal section timing |

|

|---|---|

Question type |

Average time you should spend |

Sentence Correction |

1 minute per question |

Critical Reasoning |

2 minutes per question |

Reading Comprehension |

4 minutes per passage and a little less than 1.5 minutes per question |

Following these timing guidelines will also help you pace yourself so that you have time to work on the questions at the end of the section. One of the most persistent bits of bad advice out there is that you should take more time at the beginning of the test. Don’t fall for this myth! Running short of time at the end of the test will cost you much more than you may gain from a few extra right answers up front. The testmaker imposes heavy score penalties for not reaching all questions in a section, and long strings of wrong answers due to guessing or rushing will hurt your score as well.

What this all means is that you are under some conflicting pressures. It might seem like a good idea to take extra time at the beginning to ensure that you get all the early questions right, since then the test would give you those difficult, high-value questions. But if you use up a lot of time early on, you won’t have time to finish, and your score will suffer a severe penalty. Just a handful of unanswered final questions can lower a score from the mid-90th percentile to the mid-70th percentile. Plus, if you spend all that time early on, you won’t have time to solve the hard questions you may receive as a result of your careful work, so you won’t be able to take advantage of their extra value.

So if taking more time at the beginning isn’t a good idea, does that mean you should rush through the beginning? This is also not the case. Rushing almost guarantees that you will miss some crucial aspect of a question. If you get a lot of midlevel questions wrong, the test will never give you those difficult, high-value questions that you want to reach.

If you are stuck on a question, make a guess. Even the best test takers occasionally guess, and it’s still possible to achieve an elite score if you are strategic about when and how you guess. If you start to fall behind pace, look for good guessing questions. That way you’ll reach the end of the section and have the time to earn the points for all the questions that you are capable of answering correctly and efficiently. What kinds of questions are good candidates for guessing? Ones that you know play to your weaknesses, ones that require lots of reading, or ones that look like they will involve separate evaluation of each answer choice.

Strategic Guessing

Whether you’ve run short of time or encountered a question that totally flummoxes you, you will have to guess occasionally. But don’t simply guess at random. First, try to narrow down the answer choices. This will greatly improve your chances of guessing the right answer. When you guess, you should follow this plan:

Eliminate answer choices you know are wrong. Even if you don’t know the right answer, you can often tell that some of the answer choices are wrong. For instance, on Sentence Correction questions, you can eliminate answer choice (A) as soon as you find an error in the original sentence, thus reducing the number of choices to consider.

Avoid answer choices that make you suspicious. These are the answer choices that just “look wrong” or conform to a common wrong-answer type. For example, if an answer choice in a Reading Comprehension question mentions a term you don’t remember reading, chances are it is wrong. (The next three chapters contain more information about common wrong-answer types on the Verbal section.)

Choose one of the remaining answer choices. The fewer options you have to choose from, the higher your chances of selecting the right answer.

Experimental Questions

Some questions on the GMAT are experimental. These questions are not factored into your score. They are questions that the testmaker is evaluating for possible use on future tests. To get good data, the testmaker has to test each question against the whole range of test takers—that is, high and low scorers. Therefore, you could be on your way to an 800 and suddenly come across a question that feels out of line with how you think you are doing.

Don’t panic; just do your best and keep on going. The difficulty level of the experimental questions you see has little to do with how you’re currently scoring. Remember, there is no way for you to know for sure whether a question is experimental or not, so approach every question as if it were scored.

Keep in mind that it’s hard to judge the true difficulty level of a question. A question that seems easy to you may simply be playing to your personal strengths and be very difficult for other test takers. So treat every question as if it counts. Don’t waste time trying to speculate about the difficulty of the questions you’re seeing and what that implies about your performance. Rather, focus your energy on answering the question in front of you as efficiently as possible.

HOW THE VERBAL SECTION IS SCORED

The Verbal section of the GMAT is quite different from the Verbal sections of paper-and-pencil tests you may have taken. The major difference between the test formats is that the GMAT computer-adaptive test (CAT) adapts to your performance. Each test taker is given a different mix of questions, depending on how well he or she is doing on the test. In other words, the questions get harder or easier depending on whether you answer them correctly or incorrectly. Your GMAT score is not determined by the number of questions you get right but rather by the difficulty level of the questions you get right.

When you begin a section, the computer

assumes you have an average score (about 550), and

gives you a medium-difficulty question. About half the people who take the test will get this question right, and half will get it wrong. What happens next depends on whether you answer the question correctly.

If you answer the question correctly,

your score goes up, and

you are given a slightly harder question.

If you answer the question incorrectly,

your score goes down, and

you are given a slightly easier question.

This pattern continues for the rest of the section. As you get questions right, the computer raises your score and gives you harder questions. As you get questions wrong, the computer lowers your score and gives you easier questions. In this way, the computer homes in on your score.

If you feel like you’re struggling at the end of the section, don’t worry! Because the CAT adapts to find the outer edge of your abilities, the test will feel hard; it’s designed to be difficult for everyone, even the highest scorers.

CORE COMPETENCIES ON THE VERBAL SECTION

Unlike most subject-specific tests you have taken throughout your academic career, the scope of knowledge that the GMAT requires of you is fairly limited. In fact, you don’t need any background knowledge or expertise beyond fundamental math and verbal skills. While mastering those fundamentals is essential to your success on the GMAT—and this book is concerned in part with helping you develop or refresh those skills—the GMAT does not primarily seek to reward test takers for content-specific knowledge. Rather, the GMAT is a test of high-level thinking and reasoning abilities; it uses math and verbal subject matter as a platform to build questions that test your critical thinking and problem solving capabilities. As you prepare for the GMAT, you will notice that similar analytical skills come into play across the various question types and sections of the test.

Kaplan has adopted the term “Core Competencies” to refer to the four bedrock thinking skills rewarded by the GMAT: Critical Thinking, Pattern Recognition, Paraphrasing, and Attention to the Right Detail. The Kaplan Methods and strategies presented throughout this book will help you demonstrate these all-important skills. Let’s dig into each of the Core Competencies in turn and discuss how each applies to the Verbal section.

Critical Thinking

Most potential MBA students are adept at creative problem solving, and the GMAT offers many opportunities to demonstrate this skill. You probably already have experience assessing situations to see when data are inadequate; synthesizing information into valid deductions; finding creative solutions to complex problems; and avoiding unnecessary, redundant labor.

In GMAT terms, a critical thinker is a creative problem solver who engages in critical inquiry. One of the hallmarks of successful test takers is their skill at asking the right questions. GMAT critical thinkers first consider what they’re being asked to do, then study the given information and ask the right questions, especially, “How can I get the answer in the most direct way?” and “How can I use the question format to my advantage?”

For instance, as you examine a Reading Comprehension passage, you’ll interrogate the author: “Why are you writing about Walt Whitman?” or “Why have you included this detail in paragraph 2?” For Sentence Correction questions, you’ll ask: “Why do three of the five answer choices share the same grammatical construction?” or “Is there a better way to express the idea?” For Critical Reasoning, you’ll ask the author of the argument: “What’s your main point?” or “What evidence have you presented to convince me to agree with you?”

Those test takers who learn to ask the right questions become creative problem solvers—and GMAT champs. Let’s see how to apply the GMAT Core Competency of Critical Thinking to a sample Critical Reasoning question:

One problem with labor unions today is that their top staffs consist of college-trained lawyers, economists, and labor relations experts who cannot understand the concerns of real workers. One goal of union reform movements should be to build staffs out of workers who have come up from the ranks of the industry involved.

The argument above depends primarily upon which one of the following assumptions?

Higher education lessens people’s identification with their class background.

Union staffs should include more people with first-hand industrial supervisory experience.

Some people who have worked in a given industry can understand the concerns of workers in that industry.

Most labor unions today do not fairly represent workers’ interests.

A goal of union reform movements should be to make unions more democratic.

This question asks you to identify what the author is assuming. You’ll learn more about assumptions in the Critical Reasoning chapter of this book, but for now, know that an “assumption” is something the author must believe but doesn’t state directly. A skilled critical thinker will approach this task by asking questions to uncover the author’s unstated assumption.

First of all, what does the author want to see happen? The author argues that unions should get more “workers who have come up through the ranks” into leadership. What’s her reason for this claim? She asserts that the lawyers and experts don’t understand what real workers worry about.

So if her solution is to get more rank-and-file workers into top union staffs, then what must she think these rank-and-file are capable of? The author is assuming that, unlike the college-trained experts, “workers who have come up through the ranks” can understand the concerns of the “real workers” whom the unions are supposed to represent. Scanning the answer choices, the one that matches this prediction is choice (C).

Notice how efficiently you can move through a question like this one when you engage in critical inquiry—no rereading, no falling for answer choice traps, no time wasted. As you move through this book, you’ll learn how to identify the most helpful questions to ask depending on how the test question is constructed.

Pattern Recognition

Most people fail to appreciate the level of constraint standardization places on testmakers. Because the testmakers must give reliable, valid, and comparable scores to many thousands of students each year, they’re forced to reward the same skills on every test. They do so by repeating the same kinds of questions with the same traps and pitfalls, which are susceptible to the same strategic solutions.

Inexperienced test takers treat every problem as if it were a brand-new task, whereas the GMAT rewards those who spot the patterns and use them to their advantage. Of course Pattern Recognition is a key business skill in its own right: executives who recognize familiar situations and apply proven solutions to them will outperform those who reinvent the wheel every time.

Even the smartest test taker will struggle if he approaches each GMAT question as a novel exercise. But the GMAT features nothing novel—just repeated patterns. Kaplan knows this test inside and out, and we’ll show you which patterns you will encounter on Test Day. You will know the test better than your competition does. Let’s see how to apply the GMAT Core Competency of Pattern Recognition to a sample Sentence Correction question:

A major pharmaceutical company, in cooperation with an international public health organization and the medical research departments of two large universities, is expected to announce tomorrow that it will transfer the rights to manufacture a number of tuberculosis drugs to several smaller companies.

is expected to announce tomorrow that it will transfer the

are expected to announce tomorrow that they will transfer their

are expected to announce tomorrow that they will transfer the

is expected to announce tomorrow that they will transfer the

is expected to announce tomorrow that there would be a transfer of the

Many people will look at this problem and start thinking about grammar classes they haven’t had for years. Then they’ll plug every answer choice back into the sentence to see which one works best. Did you find yourself doing that during the Pretest in this book?

There are two important patterns at work in this question that you should recognize from now on. First, choice (A) on Sentence Correction questions will always repeat the underlined portion of the original sentence. You should only ever choose (A) if there’s no error in the original sentence. If you’ve already read the original sentence, there’s never any reason to spend time reading through choice (A).

Second, notice the pronoun it in the underlined portion. Pronouns are one of seven grammar and usage topics that together make up 93 percent of the Sentence Correction issues on the GMAT. Whenever a pronoun appears in the underlined portion of the sentence, you should check whether it’s correct. Here, ask yourself what it refers to. In this case, it is the pharmaceutical company. Notice in scanning the answer choices that they, too, fall into patterns: some use it, and others use they. Recognizing this pattern lets you know what question to ask next: “To refer to a company, is the correct pronoun it or they?” For a singular noun, the correct pronoun is it. Eliminate choices (B), (C), and (D), which all use they.

Having narrowed down the choices to just two, (A) and (E), you can eliminate choice (E) because it uses an awkward, lengthy phrase that makes it less clear who will “transfer the rights.” The answer is (A); the sentence is correct as written.

Notice how efficiently you can find the correct answer when you recognize the patterns. Meanwhile, your competition, not recognizing how the GMAT works, would waste time floundering through each answer choice in turn.

Paraphrasing

The third Core Competency is Paraphrasing: the GMAT rewards those who can reduce difficult, abstract, or polysyllabic prose to simple terms. Paraphrasing is, of course, an essential business skill: executives must be able to define clear tasks based on complicated requirements and accurately summarize mountains of detail.

The test isn’t going to make it easy for you to understand questions and passages. But you won’t be overwhelmed by the complicated prose of Critical Reasoning or Reading Comprehension questions if you endeavor to make your own straightforward mental translations. Habitually putting complex ideas and convoluted wording into your own simple, accurate terms will ensure that you “get it”— that you understand the information well enough to drive to the correct answer.

Let’s see how to apply the GMAT Core Competency of Paraphrasing to the first paragraph of a sample Reading Comprehension passage. You will return to this passage in full in the Reading Comprehension chapter of this book. For now, use the first paragraph to see how Paraphrasing helps you synthesize ideas by putting them in your own words:

The informal sector of the economy involves activities that, in both developed and underdeveloped countries, are outside the arena of the normal, regulated economy and thus escape official recordkeeping. These activities, which include such practices as off-the-books hiring and cash payments, occur mainly in service industries like construction, hotels, and restaurants. Many economists think that the informal sector is an insignificant supplement to the larger formal economy. They base this belief on three assumptions that have been derived from theories of industrial development. But empirical evidence suggests that these assumptions are not valid.

One of the most crucial ways to paraphrase on the GMAT is to summarize the main idea of a paragraph. When you learn about Passage Mapping in the Reading Comprehension chapter of this book, you will see how helpful it is to write a short summary of each paragraph. Clearly, however, you do not want to waste time copying down whole sentences or phrases from the passage verbatim. Paraphrasing helps you simultaneously identify quick, short ways to record main ideas and reinforce your understanding of those ideas.

You don’t need to be an expert on economic policy to identify the main ideas in this paragraph and put them into your own words. The paragraph defines the informal sector, gives examples, then sets the stage for a debate between “many economists” and the author over how big or important the informal sector is.

On Test Day, you might write the following shorthand notes in your Passage Map for this paragraph:

¶1: Informal sector jobs; examps; econs think insig (based on 3 assumps); author disagrees

As you work through the Verbal chapters of this book, you will learn more about Paraphrasing for Reading Comprehension passages. You will also develop techniques for Paraphrasing the content of Critical Reasoning questions and interpreting the gist of what a Sentence Correction sentence is trying to say so that you can choose the answer choice that most accurately and concisely expresses that meaning.

Attention to the Right Detail

Details present a dilemma: missing them can cost you points. But if you try to absorb every fact in a Reading Comprehension passage or Critical Reasoning stimulus, you may find yourself swamped, delayed, and still unready for the questions that follow, because the relevant and irrelevant details are all mixed together in your mind. Throughout this book, you will learn how to discern the essential details from those that can slow you down or confuse you. The GMAT testmaker rewards examinees for paying attention to “the right details”—the ones that make the difference between right and wrong answers.

Attention to the Right Detail distinguishes great administrators from poor ones in the business world as well. Just ask anyone who’s had a boss who had the wrong priorities or who was so bogged down in minutiae that the department stopped functioning.

Not all details are created equal, and there are mountains of them on the test. Learn to target only what will turn into correct answers. Let’s see how to apply the GMAT Core Competency of Attention to the Right Detail to a sample Critical Reasoning question:

Police officers in Smith County who receive Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) training spend considerable time in weapons instruction and practice. This time spent developing expertise in the use of guns affects the instincts of Smith County officers, making them too reliant on firearms. In the past year in Smith County, in 12 of the 14 cases in which police officers shot a suspect while attempting to make an arrest, the officer involved had received SWAT training, although only five percent of the police force as a whole in the county had received such training.

Which of the following, if true, most strengthens the argument above?

In an adjacent county, all of the cases in which police shot suspects involved officers with SWAT training.

SWAT training stresses the need for surprise, speed, and aggression when approaching suspects.

Only 15 percent of Smith County’s SWAT training course is devoted to firearms lessons.

Among officers involved in the arrest of suspects in Smith County in the past year, the proportion who had received SWAT training was similar to the proportion who had received SWAT training in the police force as a whole.

Some Smith County officers without SWAT training have not been on a firing range in years.

You will learn more about strengthening arguments in the Critical Reasoning chapter of this book; for now, focus on finding the detail that makes a difference.

SWAT training, the author concludes in the second sentence, is making Smith County officers too reliant on firearms. The evidence in the third sentence presents you with many different numbers and figures. However, the important thing to note here is the shift in scope between the conclusion, which is about Smith County police officers in general, and the evidence, which is about the 14 cases that involved shootings during an arrest.

That “scope shift” signals that you’ve found the right detail to focus on. If the author is using data from arrests to make a point about the effects of SWAT training on the police force as a whole, it will make a difference if, for example, disproportionately many officers involved in making arrests have received SWAT training. Since you’re looking for the answer choice that strengthens the argument, you need one that equates officers making arrests to officers at large.

Answer choice (D) is the correct answer. If (D) is true, then the officers in the 14 cases are representative of officers as a whole, and the argument is strengthened.

Notice that paying Attention to the Right Detail—the one that the question hinges upon—enables you to form a prediction of what the correct answer will contain. Selecting an answer then becomes a straightforward matter of finding the choice that matches your prediction, rather than a time-consuming process of debating the pros and cons of each answer choice in turn. Throughout this book you will learn to distinguish the important from the inconsequential on the GMAT.

INTRODUCTION TO STRATEGIC READING

Since you’re reading this book and aspire to go to business school, it goes without saying that you can read. What needs saying is that the way of reading for which you’ve been rewarded throughout your academic and professional careers is likely not the best way to read on Test Day.

Normally, when you read for school, pleasure, or even work, the main things you try to get from the text are the facts—the story, who did what, what’s true or false. That way of reading may have served you well throughout your life, but on the GMAT you must read strategically.

Because Kaplan knows the test so well, we’ve identified the key structures that will get you points on the test. More importantly, we’ve identified the keywords that signal those structures and tell you what to do with them. Strategic Reading means using structural keywords to zero in on what the test will ask you about. Usually, it’s great to read in order to broaden your horizons. On Test Day, you haven’t got time for anything that doesn’t pay off in right answers.

KEYWORDS

Keywords determine the structure of a passage.

Keywords highlight lines in the text that are crucial to the author’s message.

As you see from the bullet points, keywords help you see the structure of the passage. That, in turn, tells you what part of the text is crucial to the author’s point of view, which is what the test consistently rewards you for noticing.

On the GMAT, questions could give the same facts, but the correct answers could vary depending on the author’s point of view. To see how this works, take a look at the following two facts about Bob:

Bob got a great GMAT score.

He is going to East Main State Business School.

The meaning depends on the keyword that links these facts. Fill in the supported inference for each case:

Bob got a great GMAT score. Therefore, he is going to East Main State Business School.

Supported inference about East Main State:________________________________

Bob got a great GMAT score. Nevertheless, he is going to East Main State Business School.

Supported inference about East Main State:________________________________

For the first example, you can infer that East Main State must be a good school, or at least Bob must think it is; because he got a good score, that’s where he’s going. Based on the second example, however, you can infer that East Main State must not be the kind of school where people with good scores usually go; it must not be very competitive to get in there. Notice that the facts didn’t change. The keywords “therefore” and “nevertheless” made all the difference to the correct GMAT inference.

This distinction is important because almost all GMAT questions hinge on keywords. Because it cannot reward test takers for outside knowledge, the GMAT cannot ask what you already know about East Main State—but it will ask questions to assess how well you understand what the author says about East Main State.

In Reading Comprehension and Critical Reasoning, keywords highlight the author’s opinion and logic, and they may indicate contrast, illustration, continuation, and sequence. As you continue your GMAT prep, pay close attention to keywords you encounter and what they tell you about the relationship between the information that comes before and after the keywords. Here are the most important categories of keywords and some examples of words that fall into each category.

KEYWORD CATEGORIES

Contrast: Nevertheless, despite, although, but, yet, on the other hand

Continuation: Furthermore, moreover, additionally, also, and

Logic: Therefore, thus, consequently, it follows that, because, since

Illustration: For example, we can see this by, this shows, to illustrate

Sequence/Timing: First, second, finally, in the 1920s, several steps, later

Emphasis/Opinion: Unfortunately, happily, crucial, very important, a near disaster, unsuccessful, she even ____________

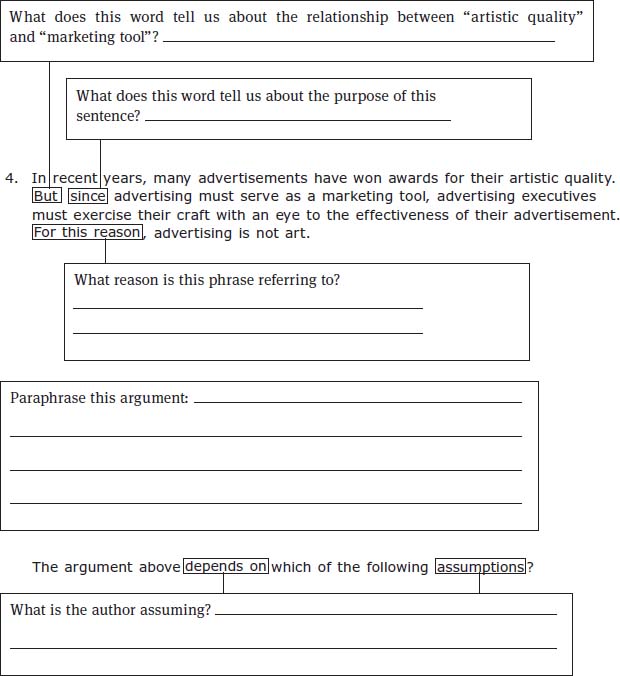

To see how keywords separate the useful from the useless on the GMAT, take a look at the following Critical Reasoning question—without the answer choices for the moment. You will learn more about analyzing arguments in the Critical Reasoning chapter of this book, but for now, the following questions will guide you through the process of breaking down an argument using keywords:

Let’s walk through the above questions in boxes, starting with the question that refers to the word “but.” You may have noted that “but” is a contrast keyword. This tells you that the author believes the terms “artistic quality” and “marketing tool” to be opposed or incompatible.

The next question refers to the word “since,” which falls under the logic category of keywords. Like the word “because,” “since” signals a reason; in terms of an argument, “since” introduces the author’s evidence.

The phrase “for this reason” refers to the evidence that came immediately beforehand—that ad executives must be concerned with effectiveness. “For this reason” also signals that the final sentence contains the argument’s conclusion.

The next box asks you to paraphrase the argument. This means that you should put the evidence and conclusion into your own succinct words: Ads aren’t art [conclusion] because they must take effectiveness into account [evidence].

Before looking at the answer choices, you need to predict exactly what you’re looking for: “What is the author assuming?” Look for the gap in your paraphrase above. The author must believe that something you have to judge based on its effectiveness cannot be art.

Now take a look at the answer choices and identify which one matches your prediction.

In recent years, many advertisements have won awards for their artistic quality. But since advertising must serve as a marketing tool, advertising executives must exercise their craft with an eye to the effectiveness of their advertisement. For this reason, advertising is not art.

The argument above depends on which of the following assumptions?

Some advertisements are made to be displayed solely as art.

Some advertising executives are more concerned than others with the effectiveness of their product.

Advertising executives ought to be more concerned than they currently are with the artistic dimension of advertising.

Something is not “art” if its creator must be concerned with its practical effect.

Artists are not concerned with the monetary value of their work.

Choice (D) matches the prediction and is the correct answer.

By attending to the keywords, you zeroed in on just what’s important to the testmaker—with no wasted effort or rereading. Strategic Reading embodies all four GMAT Core Competencies: Critical Thinking, Pattern Recognition, Paraphrasing, and Attention to the Right Detail.