CHAPTER 20

Analytical Writing Assessment

Essay Format and Structure

The Basic Principles of Analytical Writing

How the AWA Is Scored

The Kaplan Method for Analytical Writing

Breakdown: Analysis of an Argument

GMAT Style Checklist

Practice Essays

The Analytical Writing Assessment (AWA) either the first task or the last task on the GMAT, depending on which section order you choose. When the section begins, you will be presented with the Analysis of an Argument essay assignment. You will have 30 minutes to complete it.

For the essay, you will analyze a given topic and then type your essay into a simple word processing program. It allows you to do only the following basic functions:

Insert text

Delete text

Cut and paste

Undo the previous action

Scroll up and down on the screen

Spell check and grammar check functions are not available in the program, so you will have to check those things carefully yourself. One or two spelling errors or a few minor grammatical errors will not lower your score. But many spelling errors can hurt your score, as can errors that are serious enough to obscure your intended meaning.

Thirty minutes is not enough time to produce the same kind of essay you’ve written for college classes. Nor is it enough time to do a lot of trial and error as you type. It is, however, enough time to write a “strong first draft” if you plan carefully, and that’s what the essay graders are looking for.

ESSAY FORMAT AND STRUCTURE

If you are concerned that you do not type very fast, you should practice giving yourself 30 minutes to brainstorm and type AWA essays between now and Test Day. By doing so, you will get an idea of how much you can type in the time allotted; your typing speed might also improve with practice.

Your task for the Argument essay is to assess the logic and use of evidence in an argument. It doesn’t matter whether you agree or disagree with the argument’s conclusion. Rather, you need to explain the ways in which the author has failed to fully support that conclusion.

Let’s take a look at a sample prompt:

The following appeared in a memo from the CEO of Hula Burger, a chain of hamburger restaurants.

“Officials in the film industry report that over 60% of the films released last year targeted an age 8–12 audience. Moreover, sales data indicate that, nationally, hamburgers are the favorite food among this age group. Since a branch store of Whiz Vid Video Store opened in town last year, hamburger sales at our restaurant next door have been higher than at any other restaurant in our chain. Because the rental of movies seems to stimulate hamburger sales, the best way to increase our profits is to open new Hula Burger restaurants right nearby every Whiz Vid Video Store.”

Consider how logical you find this argument. In your essay, be sure to discuss the line of reasoning and the use of evidence in the argument. For example, you may need to consider what questionable assumptions underlie the thinking and what alternative explanations or counterpoints might weaken the conclusion. You may also discuss what types of evidence would strengthen or refute the argument, what changes in the argument would make it more logically sound, and what, if anything, would help you better evaluate its conclusion.

Where are the holes in the argument? In what ways does it fail to be completely convincing? Why might the plan fail? Not only do you have to identify its major weaknesses, you must also explain them.

THE BASIC PRINCIPLES OF ANALYTICAL WRITING

You aren’t being evaluated solely on the strength of your ideas. Your score will also depend on how well you express them. If your writing style isn’t clear, your ideas won’t come across, no matter how brilliant they are.

Good essay writing isn’t just grammatically correct. It is also clear and concise. The following principles will help you express your ideas in good GMAT style.

Your Control of Language Is Important

Writing that is grammatical, concise, direct, and persuasive displays the “superior control of language” (as the testmaker terms it) that earns top GMAT Analytical Writing scores. To achieve effective GMAT style in your essays, you should pay attention to the following points.

Grammar

Your writing must follow the same general rules of standard written English that are tested by Sentence Correction questions. If you’re not confident of your mastery of grammar, review the Sentence Correction chapter of this book.

Diction

Diction means word choice. Do you use the words affect and effect correctly? What about its and it’s, there and their, precede and proceed, principal and principle, and whose and who’s? In addition to avoiding errors of usage, you will need to demonstrate your ability to use language precisely and employ a formal, professional tone.

Syntax

Syntax refers to sentence structure. Do you construct your sentences so that your ideas are clear and understandable? Do you vary the length and structure of your sentences?

Keep Things Simple

Perhaps the single most important piece of advice to bear in mind when writing a GMAT essay is to keep everything simple. This rule applies to word choice, sentence structure, and organization. If you obsess about how to use or spell an unusual word, you can lose your way. The more complicated your sentences are, the more likely they’ll be plagued by errors. The more complex your organization becomes, the more likely your argument will get bogged down in convoluted sentences that obscure your point.

Keep in mind that simple does not mean simplistic. A clear, straightforward approach can still be sophisticated and convey perceptive insights.

Minor Grammatical Flaws Won’t Harm Your Score

Many test takers mistakenly believe they’ll lose points over a few mechanical errors. That’s not the case. GMAT essays should be final first drafts. This means that a couple of misplaced commas, misspellings, or other minor glitches aren’t going to affect your score. Occasional mistakes of this type are acceptable and inevitable, given that you have only 30 minutes to construct your essay. In fact, according to the scoring rubric, a top-scoring essay may well have a few minor grammatical flaws.

But if your essays are littered with misspellings and grammar mistakes, the graders may conclude that you have a serious communication problem. Keep in mind that sentence fragments are not acceptable, nor are informal structures such as bullet points or numerical enumeration (e.g., “(1)” instead of “first”). So be concise, forceful, and correct. An effective essay wastes no words; makes its point in a clear, direct way; and conforms to the generally accepted rules of grammar and style.

Use a Logical Structure

Good essays have a straightforward, linear structure. The problem is that we rarely think in a straightforward, linear way. That’s why it’s so important to plan your response before you begin typing. If you type while planning, your essay will likely loop back on itself, contain redundancies, or fail to follow through on what it sets up.

Logical structure consists of three things:

Paragraph Unity

Paragraph unity means each paragraph discusses one thing and all the discussion of that one thing happens in that paragraph. Let’s say that you’re responding to the essay prompt we just saw and one of your points is that there may have been reasons for the success of the Hula Burger restaurant other than its proximity to the Whiz Vid Video store. Your next paragraph should move on to another idea—perhaps something about the expense of opening a new Hula Burger restaurant near every Whiz Vid Video Store. If, in the middle of that next paragraph, you went back to your point about other possible reasons for the success of the Hula Burger restaurant, you’d be violating paragraph unity.

Train of Thought

This is similar to paragraph unity, but it applies to the whole essay. It’s confusing to the reader when an essay keeps jumping back and forth between the different weaknesses of an argument. Discuss one point fully, and then address the next. Don’t write another paragraph about a topic you’ve already discussed.

Flow

The basic idea of flow is that you should deliver on what you promise and not radically change the subject. If your introductory paragraph says that you will mention reasons why Hula burgers might be less popular among the 8- to 12-year-old demographic than regular hamburgers are, you need to make sure that you actually do so. Similarly, avoid suddenly expanding the scope of the essay in the last sentence.

TAKEAWAYS: THE BASIC PRINCIPLES OF ANALYTICAL WRITING

Your control of language is important.

Keep things simple.

Minor grammatical flaws won’t harm your score.

Use a logical structure.

HOW THE AWA IS SCORED

Your essays will be graded on a scale from 0 to 6 (highest). You’ll receive one score, which will be an average of the scores that you receive from each of the two graders, rounded up to the nearest half point. Your essay will be graded by a human grader as well as a computerized essay grader (the IntelliMetric™ system). The two grade completely independently of each other—IntelliMetric™ isn’t told the human’s score, nor is the human told the computer’s.

If the two scores are identical, then that’s your score. If the scores differ by one point, those scores are averaged. If they differ by more than one point, a second human will grade the essay to resolve any differences. IntelliMetric™ and the human grader agree on the same grade about 55 percent of the time and agree on identical or adjacent grades 97 percent of the time. (Only 3 percent of essays need rereading.) These figures are equivalent to how often two trained human graders agree.

IntelliMetric™ was designed to make the same judgments that a good human grader would. In fact, part of the Graduate Management Admission Council’s (GMAC’s) argument for the validity of IntelliMetric™ is that its performance is statistically indistinguishable from a human’s. Still, you should remember that it is not a human and write accordingly.

IntelliMetric’s™ grading algorithm was designed using 400 officially graded essays for each prompt. That’s a huge sample of responses, so don’t worry about whether IntelliMetric™ will understand your ideas—it’s highly likely that someone out of those 400 responses made a similar point.

Before you begin to write, outline your essay. Good organization always counts, but with a computer grader, it’s more important than ever. Use transitional phrases like first, therefore, since, and for example so that the computer can recognize structured arguments. The length of your essay is not a factor; the computer does not count the number of words in your response.

Furthermore, computers are not good judges of humor or creativity. (The human judges don’t reward those either. The standard is business writing, and you shouldn’t be making overly witty or irreverent remarks in, say, an email to a CEO.)

Though IntelliMetric™ doesn’t grade spelling per se, it could give you a lower score if it can’t understand you or thinks you used the wrong words.

Here’s what your essay will be graded on:

Structure. Does your essay have good paragraph unity, organization, and flow?

Evidence. It’s not enough simply to assert good points. Do you develop them well? How strong are the examples you provide?

Depth of Logic. Did you take apart the argument and analyze its major weaknesses effectively?

Style. The GMAC calls this “control of the elements of standard written English.” How well do you express your ideas?

Now let’s take a more in-depth look at the scoring scale so you get a sense of what to aim for. The following rubric shows how the GMAC will grade your essay based on the four categories of Structure, Evidence, Depth of Logic, and Style:

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Structure |

Lacks length and organization; does not adhere to topic. |

Lacks length and organization; unclear understanding of topic. |

Lacks length enough for real analysis; strays from topic or is partially unfocused. |

Has good basic organization and sufficient paragraphing. |

Has well-developed paragraphs and structure; stays on topic. |

Has well-developed paragraphs and structure; paragraphing works with examples. |

Evidence |

Provides few, if any, examples to back up claims. |

Provides very sparse examples to back up claims. |

Provides insufficient examples to back up claims. |

Provides sufficient examples to back up claims. |

Provides strong examples to back up claims. |

Provides very strong examples to back up claims. |

Depth of Logic |

Shows very little understanding of the argument and gives no analysis of/takes no position on it. |

Presents the writer’s views, but fails to give any analytical critique. |

Analyzes somewhat, but fails to show some key parts of the argument. |

Shows key parts of the argument adequately with some analysis. |

Shows key parts of the argument and analyzes them thoughtfully. |

Shows key parts of the argument and analyzes them with great clarity. |

Style |

Has severe and persistent errors in sentence structure and use of language; meaning is lost. |

Frequently uses language incorrectly and sentence structure, grammar, and usage errors inhibit meaning. |

Uses language imprecisely and is deficient in variety; some major errors or a number of small errors. |

Controls language adequately, including syntax and diction; a few flaws. |

Controls language with clarity, including variety of syntax and diction; may have a flaw here and there. |

Controls language extremely well, including variety of syntax and diction; may have a small flaw here and there. |

GMAC will grade your essay holistically based on the above rubric to arrive at your final score:

6: Excellent. Essays that earn the top score must be insightful, well supported by evidence, logically organized, and skillfully written. A 6 need not be “perfect,” just very good.

5: Good. A 5 essay is well written and well supported but may not be as compellingly argued as a 6. There may also be more frequent or more serious writing errors than in a 6.

4: Satisfactory. The important elements of the argument are addressed but not explained robustly. The organization is good, and the evidence provided is adequate. The writing may have some flaws but is generally acceptable.

3: Inadequate. A 3 response misses important elements of the argument, has little or no evidence to support its ideas, and doesn’t clearly express its meaning.

2: Substantially Flawed. An essay scoring a 2 has some serious problems. It may not use any examples whatsoever or support its ideas in any way. Its writing will have many errors that interfere with the meaning of the sentences.

1: Seriously Deficient. These essays are rare. A 1 score is reserved for essays that provide little or no evidence of the ability to analyze an argument or to develop ideas in any way. A 1 essay will have so many writing errors that the essay may be unintelligible.

0: No Score. A score of 0 signifies an attempt to avoid addressing the prompt at all, either by writing only random or repeating characters or by copying the prompt. You could also score a 0 by not writing in English or by addressing a completely different topic.

NR: Blank. This speaks for itself. This is what you get if you write no essay at all. Some schools will not consider your GMAT score if your essay receives an NR. By skipping the essay, you give yourself an unfair advantage—everyone else wrote an essay for 30 minutes before the other sections!

TAKEAWAYS: HOW THE AWA IS SCORED

Your AWA score does not count toward the 200–800 score for the rest of the test.

Business schools receive the text of your essay along with your score report.

The essay grading is almost pass/fail in nature: there’s a clear line between 1–3 (bad) and 4–6 (good).

A writer with a solid plan should earn a score of 4 or higher on the AWA.

THE KAPLAN METHOD FOR ANALYTICAL WRITING

You have a limited amount of time to show the business school admissions officers that you can think logically and express yourself in clearly written English. They don’t care how many syllables you can cram into a sentence or how fancy your phrases are. They care that you make sense. Whatever you do, don’t hide beneath a lot of hefty words and abstract language. Make sure that everything you say is clearly written and relevant to the topic. Get in there, state your main points, back them up, and get out. The Kaplan Method for Analytical Writing—along with Kaplan’s recommendations for how much time you should devote to each step of the Method—will help you produce the best essay you’re capable of writing in 30 minutes.

The Kaplan Method for Analytical Writing |

|

1. Take apart the argument. 2. Select the points you will make. 3. Organize using Kaplan’s essay template. 4. Write your essay. 5. Proofread your work. |

Step 1: Take Apart the Argument

Read through the prompt to get a sense of its scope.

Identify the author’s conclusion and the evidence used to support it.

You can take about 2 minutes on this step.

Step 2: Select the Points You Will Make

Identify all the important gaps (assumptions) between the evidence and the conclusion.

Think of how you’ll explain or illustrate those gaps and under what circumstances the author’s assumptions would not hold true.

Think about how the author could remedy these weaknesses. This part of the Kaplan Method is very much like predicting the answer to a Critical Reasoning Strengthen or Weaken question.

Step 2 should take about 5 minutes.

Step 3: Organize Using Kaplan’s Essay Template

Outline your essay.

Lead with your best arguments.

If you practice with the Kaplan template for the Argument essay before Test Day, organizing the essay will go smoothly and predictably. Using the Kaplan template will help you turn vague thoughts about the prompt into organized, developed paragraphs.

The organization process should take less than 1 minute.

ORGANIZING THE ARGUMENT ESSAY: THE KAPLAN TEMPLATE

PARAGRAPH 1:

SHOW that you understand the argument by putting it in your own words.

PARAGRAPH 2:

POINT OUT one flawed assumption in the author’s reasoning; explain why it is questionable.

PARAGRAPH 3:

IDENTIFY another source of the author’s faulty reasoning; explain why it is questionable.

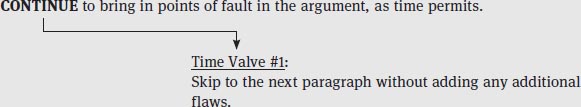

ADDITIONAL PARAGRAPHS AS APPROPRIATE:

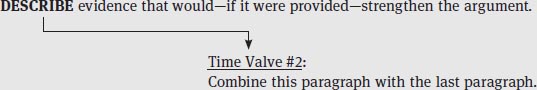

SECOND-TO-LAST PARAGRAPH:

LAST PARAGRAPH:

CONCLUDE that without such evidence, you’re not persuaded.

Step 4: Write Your Essay

Be direct.

Use paragraph breaks to make your essay easier to read.

Use transitions and structural keywords to link related ideas; they will help your writing flow.

Finish strongly.

You can afford no more than 20 minutes of typing. The other 10 minutes should be dedicated to planning and correcting.

Step 5: Proofread Your Work

Save enough time to read through the entire essay—2 minutes at minimum.

Fix any spelling, grammar, syntax, or diction errors.

Add any needed keywords to improve the flow of your ideas.

Don’t add any new ideas or change the structure of your essay. There just isn’t time.

BREAKDOWN: ANALYSIS OF AN ARGUMENT

The Instructions

Screen 1: General Instructions

The general instructions for the Argument essay will look like this:

Analytical Writing Assessment Instructions

Analysis of an Argument Essay

Time: 30 Minutes

In this part of the test, you will be asked to write a critical analysis of the argument in the prompt. You are not being asked to give your own views on the topic.

COMPOSING YOUR ESSAY: Before you begin to type, take a little time to look at the argument and plan your essay. Make sure your ideas are organized and clearly stated. Leave some time to read over your essay and make any changes you think are necessary. You will have 30 minutes to write your essay.

ESSAY ASSESSMENT: Qualified graders with varied backgrounds, including experience in business subject areas, will assess the overall quality of your analysis and composition. They will look at how well you:

identify key elements of the argument and examine them;

arrange your analysis of the argument presented;

give appropriate examples and reasons for support; and

master the components of written English.

The instructions on Screen 1 tell you to read the argument, plan your essay before writing it, and leave a little time at the end for review. Sound familiar? The Kaplan Method mirrors these steps. While the prompts for the essay vary, the general directions are always the same. Become familiar with the essay directions now so you don’t waste valuable time reading them on Test Day.

Screen 2: Specific Prompt

The next screen you go to will contain the specific essay prompt.

Read the argument and the directions that follow it, and write down any ideas that will be helpful in mapping out your essay. Begin writing your essay in the box at the bottom of this screen.

“The problem of poorly trained teachers that has plagued the state public school system is bound to become a good deal less serious in the future. The state has initiated comprehensive guidelines that oblige state teachers to complete a number of required credits in education and educational psychology at the graduate level before being certified.”

Consider how logical you find this argument. In your essay, be sure to discuss the line of reasoning and the use of evidence in the argument. For example, you may need to consider what questionable assumptions underlie the thinking and what alternative explanations or counterpoints might weaken the conclusion. You may also discuss what types of evidence would strengthen or refute the argument, what changes in the argument would make it more logically sound, and what, if anything, would help you better evaluate its conclusion.

The only part of Screen 2 that will change is the specific prompt, which is in quotation marks. The instructions above and below it will stay the same. Again, practicing with these directions now will mean that you won’t waste time reading them on Test Day.

The Stimulus

Analysis of an Argument topics will probably remind you of Critical Reasoning questions. The basic idea is similar. Just as in Critical Reasoning, the writer tries to persuade you of something—her conclusion—by citing some evidence. So look for these two basic components of an argument: a conclusion and supporting evidence. You should read the argument in the Analysis of an Argument topic in much the same way you read Critical Reasoning stimuli; be on the lookout for assumptions—the ways the writer makes the leap from evidence to conclusion.

The Question Stem

The question stem instructs you to decide how convincing you find the argument, explain why, and discuss what might improve the argument. Note that there is a right answer here: the argument always has some problems. You want to focus your efforts on finding them, explaining them, and fixing them.

Exactly what are you being asked to do here? Paraphrase the following sentences of the question stem.

Consider how logical you find this argument. In your essay, be sure to discuss the line of reasoning and the use of evidence in the argument.

Translation: Critique the argument. Discuss the ways in which it is not convincing. How and why might the evidence not fully support the conclusion?

For example, you may need to consider what questionable assumptions underlie the thinking and what alternative explanations or counterpoints might weaken the conclusion. You may also discuss what types of evidence would strengthen or refute the argument, what changes in the argument would make it more logically sound, and what, if anything, would help you better evaluate its conclusion.

Translation: Spot weak links in the argument and offer constructive modifications that would strengthen them.

Let’s use the Kaplan Method for Analytical Writing on the Analysis of an Argument topic we saw before:

“The problem of poorly trained teachers that has plagued the state public school system is bound to become a good deal less serious in the future. The state has initiated comprehensive guidelines that oblige state teachers to complete a number of required credits in education and educational psychology at the graduate level before being certified.”

Consider how logical you find this argument. In your essay, be sure to discuss the line of reasoning and the use of evidence in the argument. For example, you may need to consider what questionable assumptions underlie the thinking and what alternative explanations or counterpoints might weaken the conclusion. You may also discuss what types of evidence would strengthen or refute the argument, what changes in the argument would make it more logically sound, and what, if anything, would help you better evaluate its conclusion.

Step 1: Take Apart the Argument

First, identify the conclusion—the point the argument is trying to make. Here, the conclusion is the first sentence:

The problem of poorly trained teachers that has plagued the state public school system is bound to become a good deal less serious in the future.

Next, identify the evidence—the basis for the conclusion. Here, the evidence is the second sentence of the argument:

The state has initiated comprehensive guidelines that oblige state teachers to complete a number of required credits in education and educational psychology at the graduate level before being certified.

Finally, paraphrase the argument in your own words: the problem of badly trained teachers will become less serious because new teachers will be required to take a certain number of graduate level classes.

If you aren’t able to put the argument in your own words, you don’t yet understand it well enough to analyze it sufficiently. Don’t rush this step; you can afford a full two minutes if you need it.

Step 2: Select the Points You Will Make

Now that you’ve found the conclusion and evidence, think about what assumptions the author is making or any reasoning flaws she commits. Also, think about any unaddressed questions that you feel would be relevant.

She assumes that the courses will improve teachers’ classroom performance.

What about bad teachers who are already certified? Would they also be required to retrain?

Have currently poor-performing teachers already had this training?

Will this plan have any unintended negative consequences?

You also will need to explain how these assumptions could be false or how the questions reveal weaknesses in the author’s argument. Add to your notes:

She assumes that the courses will improve teachers’ classroom performance. What if the problem is cultural? Or if it’s a language barrier? Or if the teacher doesn’t know the subject?

What about bad teachers who are already certified? Would they also be required to retrain? If not, those bad teachers would still be in the system.

Have currently poor-performing teachers already had this training? If so, this fact demonstrates that this training won’t solve the problems.

Will this plan have any unintended negative consequences? What does this training cost? If the state has to pay for it, will that mean there is less money available for other uses? If teachers have to pay for it, will good teachers leave the system?

Then think about evidence that would make the argument stronger or more logically sound:

Evidence verifying that the training will make teachers better

Evidence that currently bad teachers have not already received this training and that they either will soon receive it or will be removed from the classroom

Evidence that the cost of the training is not prohibitive

Step 3: Organize Using Kaplan’s Essay Template

Look over the notes you’ve jotted down. Select the strongest point to be first, the next-strongest to be second, and so on. Two criteria determine whether a point is strong. One is how well you can explain it. If, for example, you aren’t sure how to explain potential negative consequences of an expensive training program, you should use that idea last—if at all. The other is how severe a problem the weakness poses to the argument’s persuasiveness. If the training doesn’t work, for example, the argument is in serious trouble.

Then decide how you’ll arrange your points. Follow the Kaplan template. The following is an example of an effective shorthand outline like the one you will create on Test Day:

¶ Restate argument (conc: solve problem of poorly trained teachers; evid: courses in education and ed. psychology)

¶ Assump: courses = better performance. Culture? Language? Subject matter? Need: evid. of relevance

¶ Assump: current bad teachers not already trained. If they have, training doesn’t work. Need: evid. of no training

¶ Assump: bad teachers will go if not trained. If not, will be bad until they retire. Need: everyone to be trained or leave

¶ Assump: not too $. If too $, other priorities suffer. Need: evid. of low $

¶ ways to strengthen arg. (needed evid.)

Remember, you may not have time to use all your points. Leaving your weakest for last means that if you run short on time, you’ll leave out your weakest point instead of your best.

Step 4: Write Your Essay

Begin typing your essay now. Keep in mind the basic principles of writing that we discussed earlier.

Keep your writing simple and clear. Choose words that you know how to use well. Avoid the temptation to make your writing “sound smarter” with overly complicated sentences or vocabulary that feels awkward.

Keep your eye on the clock and make sure that you don’t run out of time to proofread. If you need to, leave out your last point or two. (Make sure that you include at least two main points.) Let’s pretend that the writer of the following essay had only six minutes left on the clock after the third paragraph. She wisely chooses neither to rush through her final paragraph nor to skip proofreading. Instead, she leaves out her point about cost and uses the time valve in the template of combining the next-to-last and last paragraphs.

The author concludes that the present problem of poorly trained teachers will become less severe in the future because of required credits in education and psychology. However, the conclusion relies on assumptions for which the author does not supply clear evidence.

The author assumes that the required courses will produce better teachers. In fact, the courses might be entirely irrelevant to the teachers’ failings. If, for example, the prevalent problem is cultural or linguistic gaps between teacher and student, graduate-level courses that do not address these specific issues probably won’t do much good. The courses also would not be heplful for a teacher who does not know their subject matter.

In addition, the author assumes that currently poor teachers have not already had this training. In fact, the author doesn’t mention whether some or all of the poor teachers have had similar training. If they have, then the training seems not to have been effective and the plan should be rethought.

Finally, the author assumes that poor teachers currently working will either stop teaching in the future or will receive training. The author provides no evidence, though, to indicate that this is the case. As the argument stands, it’s highly possible that only brand-new teachers will be receiving the training and the bright future to which the author refers is decades away.

To strengthen the argument, the author must provide several pieces of evidence to support his assumptions. First of all, the author’s implicit claim that the courses will improve teachers could be strengthened by providing evidence that the training will be relevant to teachers’ problems. The author could also make a stronger case by showing that currently poor teachers have not already had training comparable to the new requirements. Finally, the author’s argument can only hold in the presence of evidence that all teachers in the system will receive the training—and will then change there teaching methods accordingly. In its current state, the argument relies too heavily on unsupported assumptions to be convincing.

Step 5: Proofread Your Work

Save a few minutes to go back over your essay and catch any obvious errors. Look over the essay above. It has at least four grammatical errors and is missing at least one keyword. By leaving herself ample proofreading time, our author will be able to find them.

Paragraph 1:

The phrase “because of required credits” is awkward and unclear. Change to “because the state will require teachers to complete credits.”

Paragraph 2:

Add a keyword to the beginning of the paragraph. Since it is the first assumption discussed, “The author assumes …” should be changed to “First, the author assumes….”

The last sentence could be improved: “The courses also would not be heplful for a teacher who does not know their subject matter.” For one thing, “heplful” should be “helpful.” For another, “a teacher” is singular, but “their” is plural. Change “their” to “his” or “her.”

Paragraph 3: no errors

Paragraph 4:

There’s an awkward phrase about halfway through: “only brand-new teachers will be receiving the training.” There’s no need for anything but simple future tense: “only brand-new teachers will receive the training.”

Paragraph 5:

In the next-to-last sentence, “there teaching methods” should be “their teaching methods.”

The best way to improve your writing and proofreading skills is practice. When you practice responding to AWA prompts, do so on a computer—but to mimic test conditions, don’t use the automatic spell check or grammar check. Write practice essays using the prompts at the end of this chapter, those provided by the testmaker at mba.com, or those in the Official Guide for GMAT Review. The pool of prompts provided by the testmaker contains the actual prompts from which the GMAT will select your essay topic on Test Day.

GMAT STYLE CHECKLIST

On the GMAT, there are three rules of thumb for successful writing: be concise, be forceful, and be correct. Following these rules is a sure way to improve your writing style—and your score. Let’s look at each one in more depth.

Be Concise

Cut out words, phrases, and sentences that don’t add any information or serve a necessary purpose.

Watch out for repetitive phrases such as “refer back” or “absolutely essential.”

Don’t use conjunctions to join sentences that would be more effective as separate sentences.

Don’t use needless qualifiers such as “really” or “kind of.”

Examples

Wordy: The agency is not prepared to undertake expansion at this point in time.

Concise: The agency is not ready to expand.

Redundant: All of these problems have combined together to create a serious crisis.

Concise: Combined, these problems create a crisis.

Too many qualifiers: Ferrara seems to be sort of a slow worker.

Concise: Ferrara works slowly.

Be Forceful

Don’t refer to yourself needlessly. Avoid pointless phrases like “in my personal opinion”; even phrases such as “I agree” or “I think” are considered stylistically weak.

Avoid jargon and pompous language; it won’t impress anybody. For example, “a waste of time and money” is better than “a pointless expenditure of temporal and financial resources.”

Don’t use the passive voice. Use active verbs whenever possible.

Avoid clichés and overused terms or phrases (for example, “beyond the shadow of a doubt”).

Don’t be vague. Avoid generalizations and abstractions when more specific words would be clearer.

Don’t use weak sentence openings. Be wary of sentences that begin with “there is” or “there are.” For example, “There are several ways in which this sentence is awkward,” should be rewritten as “This sentence is awkward in several ways.”

Don’t be monotonous; vary sentence length and style.

Use transitions to connect sentences and make your essay easy to follow.

Examples

Needlessly references self: Although I am no expert, I do not think privacy should be valued more than social concerns.

Speaks confidently: Privacy should not be valued more than social concerns.

Uses passive voice: The report was compiled by a number of field anthropologists and marriage experts.

Uses active voice: A number of field anthropologists and marriage experts compiled the report.

Opens weakly: It would be of no use to fight a drug war without waging a battle against demand for illicit substances.

Opens strongly: The government cannot fight a drug war effectively without waging a battle against the demand for illicit substances.

Uses cliché: A ballpark estimate of the number of fans in the stadium would be 120,000.

Employs plain English: About 120,000 fans were in the stadium.

Be Correct

Observe the rules of standard written English. The most important rules are covered in the Sentence Correction chapter of this book.

Examples

Subject and verb disagree: Meredith, along with her associates, expect the sustainable energy proposal to pass.

Subject and verb agree: Meredith, along with her associates, expects the sustainable energy proposal to pass.

Uses faulty modification: Having worked in publishing for 10 years, Stokely’s resume shows that he is well qualified.

Uses correct modification: Stokely, who has worked in publishing for 10 years, appears from his resume to be well qualified.

Uses pronouns incorrectly: A retirement community offers more activities than a private dwelling does, but it is cheaper.

Uses pronouns correctly: A retirement community offers more activities than a private dwelling does, but a private dwelling is cheaper.

Has unparallel structure: The dancer taught her understudy how to move, how to dress, and how to work with choreographers and deal with professional competition.

Has parallel structure: The dancer taught her understudy how to move, dress, work with choreographers, and deal with professional competition.

Fragmented sentence: There is time to invest in property. After one has established oneself in the business world, however.

Complete sentence: There is time to invest in property, but only after one has established oneself in the business world.

Run-on sentence: Antonio just joined the athletic club staff this year, however, because Barry has been with us since 1975, we would expect Barry to be more skilled with the weight-lifting equipment.

Correct sentence: Antonio joined the athletic club staff this year. However, because Barry has been with us since 1975, we would expect him to be more skilled with the weight-lifting equipment.

PRACTICE ESSAYS

Directions: Write an essay on each of the three topics below. The writing should be concise, forceful, and grammatically correct. After you have finished, proofread to catch any errors. Allow yourself 30 minutes to complete each essay. Practice writing under timed conditions so that you get a feel for how much you can afford to write while leaving enough time to proofread.

Essay 1

The following appeared in a memo from a staff member of a local health care clinic.

“Many lives might be saved if inoculations against cow flu were routinely administered to all people in areas where the disease is detected. However, since there is a small possibility that a person will die as a result of the inoculations, we cannot permit inoculations against cow flu to be routinely administered.”

Consider how logical you find this argument. In your essay, be sure to discuss the line of reasoning and the use of evidence in the argument. For example, you may need to consider what questionable assumptions underlie the thinking and what alternative explanations or counterpoints might weaken the conclusion. You may also discuss what types of evidence would strengthen or refute the argument, what changes in the argument would make it more logically sound, and what, if anything, would help you better evaluate its conclusion.

After writing your essay, compare it to the sample responses that follow. Don’t focus on length, as word count is not part of the grading criteria. Rather, focus on how logical the structure is and whether the essay makes its points in a clear and straightforward style.

Student Response 1 (as written, including original errors):

The writer argues that innoculations against cow flu shouldn’t be administered because there is a possibility of a person dying from the innoculation. The flaw in this argument is suggested by the writer’s use of the phrases “many lives” and “small possibility.” These are vague words, but, they imply, that cow flu itself poses a greater risk to people in an area where the disease is present than the prevention against it. If this is the case, then the writer’s argument is greatly weakened.

The writer could make the argument better by showing that the overall death rate from cow flu among those who haven’t been innoculated in an area where cow flu has been detected is lower than the death rate from the vaccine among individuals who have been given the innoculation. This would show that the vaccine poses a greater risk than the disease itself. Also, it would be good to know whether some people are more likely to die from the innoculation than others and whether these people can be located. It’s possible that those people who are most at risk from the innoculation are also most at risk from the disease itself, in which case the innoculation might do no greater harm than the disease would, and would also save the lives of many who were not in this high risk group. On the other hand, if those people who are most at risk from the vaccine are not at a very high risk from the disease, then maybe we can exempt them from the vaccine, but continue to administer it to those people who it will help.

Analysis 1:

Structure: The writer gives his evaluation of the argument in paragraph 1. However, the organization breaks down in paragraph 2, where the writer tries to cover too much. In this paragraph, the writer discusses ways of strengthening the argument, the need for more information, and alternative possibilities for the scenario. A better-written essay might have split paragraph 2 into several different paragraphs, each covering one topic.

Evidence: The writer does not fully support his position with specific examples. Rather, he writes vaguely of different possibilities. While this is not completely wrong, it’s also not the type of concrete support that is needed here.

Depth of Logic: This is probably the weakest area in the essay. The writer fails to fully develop his ideas. He looks at the problem only through a cost-benefit lens—which way saves more lives?—as opposed to questioning whether any risk of death means that we shouldn’t routinely inoculate.

Style: The writing style is flat and the first sentence in paragraph 2 is long and convoluted. The ideas in paragraph 2 seem strung together.

This essay would earn a score of 3. While the writer has some decent ideas and shows adequate writing ability, the structure of the essay is poor, the logic fails to show some parts of the author’s argument, and the writer inadequately develops support for his own points. Had this student used the same ideas, but developed and organized them according to the Kaplan template, he would almost assuredly have earned a score of 4 or better.

Student Response 2 (as written, including original errors):

The argument above states that inoculations against cow flu could be useful in combating the disease, but, due to the risk of death from the inoculations themselves, the vaccines should not be widely administered. This argument relies on several unsupported assumptions and therefore fails to be persuasive.

The argument against widespread inoculations is rooted in the assumption that the risk of death from the inoculations is greater than the risk of death from cow flu. However, the author provides no evidence to support this key assumption. Without specific statistics regarding the death rates from inoculations and cow flu, we cannot assume that one outweighs the other: cow flu and the inoculations may be equally risky, or cow flu may in fact be riskier than the inoculations. In addition, the language of the argument appears to contradict its primary assumption. The author states that “many lives” could be saved by inoculations, but there is a “small possibility” of death from the inoculations. These terms suggest that the risk from cow flu is greater than that of the inoculations, further weakening the author’s position that inoculations should not be routinely administered.

Additionally, the author takes an “all or nothing” position, suggesting that inoculations must be widely administered or not administered at all. This position ignores the possibility of variation in rates of infection and effects of the inoculation in different environments. The vaccine may pose a serious risk to those relatively unaffected by cow flu, while posing little risk to those most impacted by cow flu. In this case, vaccines administered to select portions of the population might save the most lives while putting the fewest lives in danger.

To make this argument persuasive, the author needs to present specific evidence to support the argument’s assumptions. For instance, details regarding the number of deaths caused by cow flu and the vaccine would clarify the relative risks of the flu and the inoculations, allowing an accurate evaluation of the merits and risks of the vaccine. Also, a less extreme stance on inoculations—one that allowed for selective administration of the inoculations based upon an area’s risk for the disease—would provide a more realistic solution to the challenge of balancing the dangers of cow flu and inoculations. Without such changes, the conclusion of this argument remains unconvincing.

Analysis 2:

Structure: The writer of this essay has clearly used the Kaplan template to her benefit. She frames the argument succinctly in the first paragraph. In each of the middle paragraphs, she lays out one major problem in the argument’s reasoning and explains with clear support why it is a problem. In the final paragraph, the writer introduces evidence that would strengthen the argument and then draws her conclusion.

Evidence: The evidence is solid. The writer could have brought in counterexamples to support criticisms of the argument, but this is not a fatal flaw.

Depth of Logic: The logic in this essay is much stronger than in the last. The organization of the essay leaves few gaps in the reasoning.

Style: The writing style is superior, with fewer (although not zero) grammatical mistakes and much stronger flow.

This essay would receive a score of 6 from the GMAT graders. It is not perfect, but the graders do not expect perfection. The conclusion is somewhat clunky, and the writer missed one or two opportunities to strengthen her point. However, it is still a very strong essay in all four categories of evaluation, and it is a vast improvement over the earlier effort.

Essay 2

The following appeared in a memo from the regional manager of Luxe Spa, a chain of high-end salons.

“Over 75% of households in Parksboro have Jacuzzi bathtubs. In addition, the average family income in Parksboro is 50% higher than the national average, and a local store reports record-high sales of the most costly brands of hair and body care products. With so much being spent on personal care, Parksboro will be a profitable location for a new Luxe Spa—a salon that offers premium services at prices that are above average.”

Consider how logical you find this argument. In your essay, be sure to discuss the line of reasoning and the use of evidence in the argument. For example, you may need to consider what questionable assumptions underlie the thinking and what alternative explanations or counterpoints might weaken the conclusion. You may also discuss what types of evidence would strengthen or refute the argument, what changes in the argument would make it more logically sound, and what, if anything, would help you better evaluate its conclusion.

After writing your essay, compare it to the sample response that follows.

Student Response (as written, including original errors):

Though it might seem at first glance that the regional manager of Luxe Spa has good reasons for suggesting that Parksboro would be a profitable location for a new spa, a closer examination of the arguments presented reveals numerous examples of leaps of faith, poor reasoning, and ill-defined terminology. In order to better support her claim, the manager would need to show a correlation between the figures she cites in reference to Parksboro’s residents and a willingness to spend money at a spa with high prices.

The manager quotes specific statistics about the percentage of residents with Jacuzzis and the average income in Parksboro. She then uses these figures as evidence to support her argument. However, neither of these statistics as presented does much to bolster her claim. Just because 75% of homes have Jacuzzis doesn’t mean those homeowners are more likely to go to a pricey spa. For instance, the presence of Jacuzzis in their houses may indicate a preference for pampering themselves at home. Parksboro could also be a planned development in the suburbs where all the houses are designed with Jacuzzis. If this is the case, than the mere ownership of a certain kind of bathtub should hardly be taken as a clear indication of a person’s inclination to go to a spa. In addition, the fact that Parksboro’s average family income is 50% higher than the national average is not enough on its own to predict the success or failure of a spa in the region. Parksboro may have a very small population, for instance, or a small number of wealthy people counterbalanced by a number of medium- to low-income families. We simply cannot tell from the information provided. In addition, the failure of the manager to provide the national average family income for comparison makes it unclear if earning 50% more would allow for a luxurious lifestyle or not.

The mention of a local store’s record-high sales of expensive personal care items similarly provides scant evidence to support the manager’s assertions. We are given no indication of what constitutes “record-high” sales for this particular store or what “most costly” means in this context. Perhaps this store usually sells very few personal care products and had one unusual month. Even if this one store sold a high volume of hair- and body-care products, it may not be representative of the Parksboro market as a whole. And perhaps “most costly” refers only to the most costly brands available in Parksboro, not to the most costly brands nationwide. The manager needs to provide much more specific information about residents’ spending habits in order to provide compelling evidence that personal care ranks high among their priorities.

To make the case that Parksboro would be a profitable location for Luxe Spa, the regional manager should try to show that people there have a surplus of income and a tendency to spend it on indulging in spa treatments. Although an attempt is made to make this very argument, the lack of supporting information provided weakens rather than strengthens the memo. Information such as whether there are other high-end spas in the area and the presence of tourism in the town could also have been introduced as reinforcement. As it stands, Luxe Spa would be ill-advised to open a location in Parksboro based solely on the evidence provided here.

Analysis:

Structure: The use of the Kaplan template is evident here. In the first paragraph, the writer demonstrates his understanding of the argument and gives a summary of its flaws. Each paragraph that follows elaborates on one flaw in the author’s reasoning. The final paragraph introduces evidence that, if provided, would strengthen the argument.

Evidence: The evidence is strong. The writer develops his points by providing examples to explain why the author’s reasoning is questionable. Some minor flaws are evident, as in the second paragraph, when the writer misses an opportunity to point out that a small population might not be enough to support a spa.

Depth of Logic: Once again, the organization of the essay enhances its depth of logic. The writer takes apart the argument methodically and provides clear analysis of each part.

Style: The writing style is smooth and controlled, and grammar and syntax errors are minimal to nonexistent.

This essay would score a 6. The writer makes a very strong showing in all four categories of the grading rubric.

Essay 3

The following appeared in a document released by a community’s arts bureau:

“In a recent county survey, 20 percent more county residents indicated that they watch TV programs dedicated to the arts than was reported eight years ago. The number of visitors to our county’s museums and galleries over the past eight years has gone up by a comparable proportion. Now that the commercial funding public TV relies on is facing severe cuts, which will consequently limit arts programming, it is likely that attendance at our county’s art museums will also go down. Therefore, public funds that are currently dedicated to the arts should be partially shifted to public television.”

Consider how logical you find this argument. In your essay, be sure to discuss the line of reasoning and the use of evidence in the argument. For example, you may need to consider what questionable assumptions underlie the thinking and what alternative explanations or counterpoints might weaken the conclusion. You may also discuss what types of evidence would strengthen or refute the argument, what changes in the argument would make it more logically sound, and what, if anything, would help you better evaluate its conclusion.

After writing your essay, compare it to the sample response that follows.

Student Response (as written, including original errors):

In a time of threatened scarcity of funding, a community arts organization is asking to shift public arts funds partly to public television. The organization cites a recent survey of county residents that shows a 20 percent self-reported increase in arts TV-watching over the last eight years concomitant with a similar, documented increase in local museum and art gallery attendance. This earnest plea is understandable, but the underlying rationale for shifting funding is flawed and lacks sufficient substantiation.

First, the author may be confusing correlation with causation. Does the survey—even if we accept its findings as valid—really indicate that people went to museums as a result of seeing arts programming on television? Its quite possible that there are alternate reasons for the increase in attendance at museums, such as partnerships with schools, discount programs for senior citizens, introduction of IMAX theaters, or popular traveling exhibits. Alternatively, people may be watching more arts programming on television as a direct result of being lured into museum attendance for reasons that have nothing to do with television.

A second reason to be hesitant to adopt the recommended funding shift is that it assumes that there are only two viable sources of funding for public television: commercial and public. Before it resorts to diverting public funds from other arts organizations, public television has the option to pursue direct fundraising from viewers; these newly enthusiastic television arts program viewers may be delighted to support such programming directly. Public television has a unique opportunity to reach its audience in a way that is more elusive to smaller art museums. It is potentially in a superior position to recover from reduced corporate funding without needing to rely more heavily on public funds.

Conversely, it is possible that the author knows more than he has shared about a connection between public television watching and local museum attendance. For instance, there may have been some specific partnerships in the last eight years between local museums and local public television stations, including specific programming designed to tie in with current museum exhibitions. The recent survey to which the author alluded may have referenced direct ties between the television programming and museum attendance. Such data would make it more likely that increasing the public funding for public television would also directly benefit local museums.

Until more information is provided to us, however, we cannot accept the authors’ argument for a shift in public funds to local public television as a way to support local art museums.

Analysis:

Structure: This essay is very well organized. The essayist’s use of transitions is particularly strong here, as she leads the reader through the points of fault in the argument and describes evidence that could potentially strengthen the argument.

Evidence: The essayist provides multiple, strong examples that strengthen her major points.

Depth of Logic: The essayist accurately identifies the assumptions inherent in the argument and develops her points by proposing plausible alternative explanations for the evidence the argument’s author cites.

Style: The essayist has a few problems with misplaced apostrophes; otherwise, the grammar and syntax are strong.

This essay would score a 6. It is an excellent example of how following the Kaplan template will help you organize your ideas into a convincing essay. After the introduction, two paragraphs develop and support the author’s two main points, followed by a paragraph describing how the argument could be strengthened and a clear conclusion.