HABIT 13

Put on Your Marketing Hat

When you read any book about investing, you’re likely to read a lot about financials: sales, earnings, cash flow, balance sheet, price-to-earnings ratios, and so forth. No doubt, these fundamentals are important, but I find that most investing books stop short of really helping you understand a business.

If you read Habit 12: Don’t Forget the Intangibles, you already have a pretty good idea that there is a lot more to a business than the financials, particularly if you’re trying to predict the future, which is in fact what most of us investors are doing. Financials are a mirror into the past, while a company’s intangibles are a spyglass into the future.

Among the most important intangibles in predicting the future is marketing. How does the company position itself compared to its competition? How does it position and price its products? How—and how well—does it acquire and retain customers? Does it have a solid brand? Does it control its marketplace well enough to raise prices and thus profits? What are its greatest strengths and weaknesses in its markets? What are the opportunities and threats?

These are some of the questions that sharp investors habitually ask about their investments and prospective investments. These are questions about the company’s markets and marketing. They’re about a company’s strategic marketing, which involves decisions about how to develop, position, and price products and services, and its tactical marketing—how it actually presents itself to the marketplace.

As a habit, I suggest that you put on your marketing hat when evaluating an investment. Pretend, at least for a few minutes, that you’re the Chief Marketing Officer for that business. This “habit” cannot possibly be a complete marketing course, but here’s a quick overview of some of the concepts and tools good marketers use.

Is the Company Positioned for Success?

Positioning refers to how a company wants to play and develop its products and services for the marketplace. It is how a company wants to compete. Is the company competing on price alone or some other basis? Does the company have a solid portfolio of products or is it a one-hit wonder? Is service an important part of the offering? Location? Customer experience?

You might think of it as you would think of three big retailers: Walmart, Target, and Nordstrom. Walmart is the low-price leader with a strategy of establishing stores everywhere, high volumes, and low margins. At the other end is Nordstrom (or Neiman Marcus or another high-end retailer you might be familiar with locally) with relatively high prices, exclusive brands, and high-touch service. Target falls somewhere in between—more elegant merchandise, more pleasant shopping conditions, some but not high-touch service, and moderate prices. As an example, when you size up a business, decide whether it’s the Walmart, Nordstrom, or Target of the industry. Of course, there are other continuums you can use.

Once you decide how a company is positioned, ask yourself how strong the competition is in that position or segment, and whether the company you’re evaluating is succeeding, failing, or if it falls somewhere in between.

Look for Niche Players

A niche, in marketing, is a small but meaningful segment of a market that can be dominated by a single company. That dominance allows the company to dictate the market, that is, to set the price and what’s offered for the price. In many cases, the company is so important and visible to that niche that it doesn’t really have to advertise or market its services.

Coffee purveyor Starbucks is a good example. The coffee market is deep and wide, but Starbucks in the beginning saw a niche for high-quality coffee served in a pleasant, upscale, European-style environment. They dominated that niche and did a lot of other things well, too, becoming a third place beyond the home and traditional workplace for on-the-go workers, moms, and college students. For millions, they effectively replaced the neighborhood tavern. They have come to dominate the high-end, locally-served coffee niche, commanding higher prices than the competition with virtually no advertising.

Many other successful companies dominate their niches too, whether it is with products, service, or simply location. When evaluating a company, ask yourself whether it dominates any niches, or if it must compete head to head with other strong challengers for a much broader market. Good players in good niches tend to make good investments—especially when the niche becomes an entire market—as the Starbucks and Apples of the world have found.

Does the Company Have a Solid Product Portfolio?

A company that sells good products to good niches in growing markets will do well. A company that sells bad or “me too” products to flat or declining markets, with no “niche” presence or pricing power, will find itself in an eternal struggle.

Marketers use all sorts of tools to analyze and diagram their businesses. It seems that almost anything in business—or in life, for that matter—can be put in four quadrants to help figure it out and make the right decisions. (Interestingly, psychologists like to do this too.)

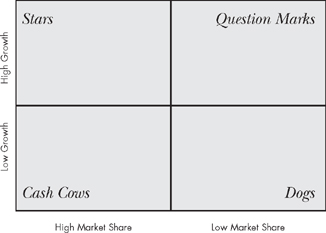

One of the more popular grids in use in business today was created and used by the Boston Consulting Group way back in 1970. It is called a “growth-share matrix” or more informally, a “BCG Box or simply a “Boston Box.”

Figure 13.1 illustrates a basic Boston Box. Here’s how it works. You take a product—or an assortment of products—and position it according to the matrix. If it has a high market share in a high-growth market, it is a “Star.” You can think of anything that Apple makes today as a “Star,” with the possible exception of MacBooks, which still might be considered a “Question Mark” with high-growth and relatively low (but growing!) market share. How do you know the growth and share numbers? It’s very difficult, but you can get an idea from what you observe in the marketplace and/or what you read in the financial press.

Finally, we have “Dogs” with low growth and low market share—products most companies would likely want to either get rid of or do better with. Interesting is the “Cash Cow”—low-growth products that produce high margins—likely because the company dominates a niche. Drug companies have a lot of cash cows, which are “milked” to produce cash to invest in R&D for new drugs. Big SUVs were cash cows for U.S. auto companies until they got sick on high gas prices.

The intention of this exercise is to look at a company’s products and decide if most are stars, cash cows (good), question marks (?) or dogs (bad). Again, a lot of this will be based on your intuition and is hard to quantify, but it helps you to decide whether a company is on the right track.

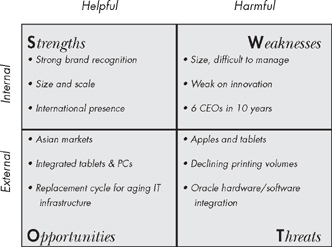

Consider a simple example I did for Hewlett-Packard, shown in Figure 13.2. The company has clear examples of products in all four quadrants (not every company will). Its “Blade Servers,” the simple servers designed to scale up capacity in a data center, website installation, etc., are one of its “star” products, offering high margins in a high-growth market. (Again, it helps to read a lot or have a “smart friend” in the business to help.) Its network storage products are in a rapidly growing market, but the company has relatively low share, so those products are question marks. The ink cartridges have long been a cash cow—very profitable products but in today’s world, a very slow growing market. Finally, PCs could be the dogs. HP does have the number one worldwide market share position, but with less than 20 percent share, it doesn’t really reap the benefits of high share.

FIGURE 13.2: BOSTON BOX MATRIX—HEWLETT-PACKARD

HP as a whole is kind of a question mark itself. The cash cow ink cartridge market may actually be declining as tablets replace print volume and competitors refill cartridges cheaply. Part of the exercise is to determine direction—for instance, are cash cows or stars losing their cash cow or star status?

In fact, sometimes it helps to simply place the whole company within this framework. HP is probably, as a whole, somewhere between a dog and a question mark, while Apple is clearly a star. Starbucks might be somewhere between a star and a cash cow, and most utilities and energy companies are obvious cash cows. Chipotle Mexican Grill is somewhere between a question mark and a star; unless you define its market narrowly as the “hand-made, you-pick-it” burrito market, it is still a minor share player in a huge fast-food market.

Naturally, you want to buy stars or question marks if you have a high-risk tolerance and cash cows if you have a lower risk tolerance. Companies that fund star products with cash cow cash, like drug makers and, in the old days, HP, are usually a good bet—if they’re using their cash wisely.

Product Evolution? Or Just a Flash in the Pan?

Some companies are one-trick ponies. They sell one product and sell it well. Sometimes that product has a quick rise and fall in the marketplace, like netbook computers or video rentals, and sometimes it lasts forever. Other companies have a well-thought-out and well-executed product evolution. The evolutionary path makes sense, retains or even increases customer loyalty, and in the best cases, becomes widely anticipated and generates excitement. (Again, think of those masters of the marketing universe, Apple.)

Restaurants, especially new restaurant concepts, are notorious for being flash-in-the-pan, one-trick ponies that ultimately crash and burn (anyone remember Victoria Station?). Some appear that way but find ways to continue and build (many thought Starbucks was simply a trendy thing that would disappear). I’m still not sure that Chipotle is here to stay, but it’s really in vogue at the time of this writing. Software companies also flirt with this danger, unless they command their niche and keep developing good follow-on products (e.g., Microsoft, Adobe).

Try, as a marketer/investor, to visualize where a company’s products might be five years from now, in an era of ever-more-rapid change in technology and consumer tastes.

Is the Company Gaining or Losing Share?

As touched on above, whether a company has high or low market share is important. Just as important—maybe more so—is whether the company is gaining or losing share. Again, this can be inferred from reading the press or just seeing what’s going on “on the street.” Are there fewer HP products on the shelves at retailers these days? Share may be in trouble.

Mindshare is also important. As marketers like to say, it’s all about the “share of customer” or “share of wallet” belonging to that customer. Is the company a hero to its customers, as is Apple or John Deere or Costco? Or is it likely to be thrown to the winds as soon as another competitor comes along or if one lowers the price a buck or two? How strong is the affinity between the company and its customers? And is it getting better (Apple) or getting worse (Sears, Toyota, Netflix)?

Bottom line: Is the company winning in the marketplace? Winning with customers?

Does the Company Present Itself Effectively?

This one seems pretty obvious, but if you like how the company presents itself to the public, mainly through advertising, its web presence, and in some cases, its public relations and press releases, chances are others will like it too. Companies with weak, boring, or muddied messages just don’t work in today’s world of information overload and quick uptake.

Clear, creative, insightful, informative messages that convey value work; bland, confusing, self-serving messages that show no value (like many from the oil industry, for instance) generally don’t. Stick with the companies that have a solid and well-communicated message.

Think SWOT

Finally, we get to an exercise played not only by marketers but by business leaders in executive suites everywhere—the SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis. As Figure 13.3 shows, it’s really pretty simple. Just analyze each company for what you see as its Strengths (helpful characteristics internal to the company, like lots of cash or strong brands or great products), and its Weaknesses (self-inflicted harmful characteristics like debt, bad products, high warranty costs, high input costs, poor sales channels, etc.).

FIGURE 13.3: SWOT ANALYSIS FRAMEWORK.

Once you have these “internal” characteristics down, move on to the “Opportunities” and “Threats” in the marketplace. I’ve furnished an example, again for HP, in Figure 13.4:

Note that I have limited each quadrant to three items, the ones I consider most important. Doubtless there are others, and you can probably think of others when you consider your companies. You may want to list them all or may want to do as I did and cut them down to the most important among the many.

As you do this, you’ll want to think about whether any of the Weaknesses or Threats are absolute showstoppers, like an exceptionally weak financial position or obsolete technology. Again, like much else in marketing, it’s a matter of judgment but can be helped along by personal observation and expert opinions.

• Think about companies you own—or want to buy—as a marketer would.

• Decide where the company positions itself (Walmart-Target-Nordstrom as an example), and decide whether the company is succeeding with this positioning.

• Look for solid niche players and signs of niche leadership.

• Look at a company’s product portfolio—and the company itself—to seek out Stars and Cash Cows.

• Determine if the company is gaining share—and share (mindshare) of customer.

• Decide whether the company presents itself clearly and effectively in the marketplace. Does it convey value to its customers?

• Identify three Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats for each company. Decide if any of the Weaknesses or Threats are showstoppers.