“With his own breath Verhaeren enlarged the horizon of the little motherland, and like Balzac with his thankless mild Touraine, he grafted onto the Flemish plains the beautiful human kingdom of his ideality and his art.”

FRANCIS VIELÉ-GRIFFIN1

“Of Verhaeren one might say that he met this surprising challenge of ‘incarnating a country which did not exist’, of granting it a soul, a great soul, and making it coincide with the universal soul. Emerging from a debilitating terrain, he managed by an extraordinary effort of comprehension and assimilation to become the poet of his century and the mirror of European civilisation.”

JACQUES MARX2

“A dark day, I still remember clearly and will never forget. I took out his letters, his many letters, all of them laid out in front of me, so as to read them, be alone with them, to bring to a close that which was over now, for I knew I would never receive another. And yet I could not. There was something within that prevented me from saying farewell to him who resided in me as proof incarnate of my own existence, of my faith on earth. The more I told myself he was dead, the more I felt how much he lived and breathed in me still and even these words which I am writing to take leave of him have merely revived him. For only the admission of a great loss attests to the true possession of that which must perish and only the unforgettable dead are fully alive in our midst!”

STEFAN ZWEIG3

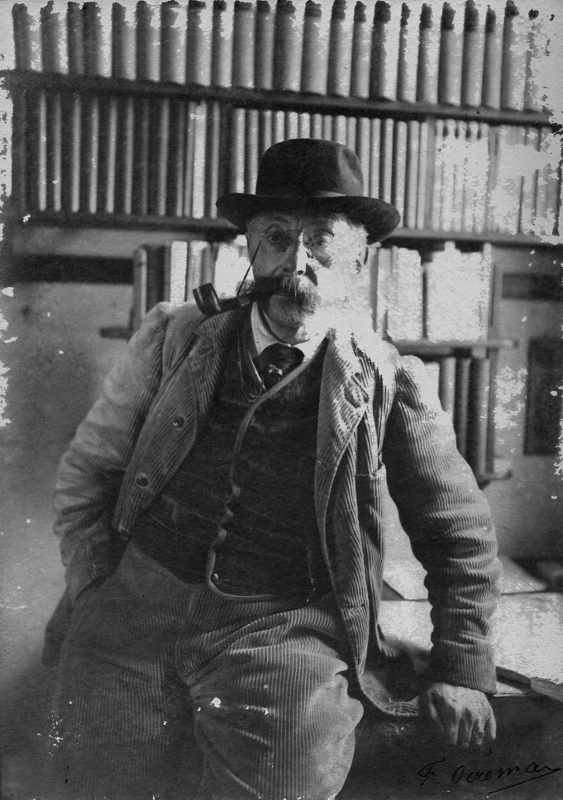

“My heart is a burning bush that sets my lips on fire…”: this expressively visionary line from a poem by Emile Verhaeren, Belgium’s most celebrated and significant poet of the modern age, serves not only to signal an exceptional lyrical gift, but also reveals the strain of his fiery Flemish nature. Born and educated in Flanders but, like his contemporaries, drawn to write in French, the language favoured by the cultured middle classes and intellectual circles of the period, Verhaeren produced a body of work that encompasses the period of Symbolism of the late 1880s and 1890s and also witnesses the first tentative steps of Modernism in a new century. It was this new century and its unprecedented social, technological and scientific eruptions that Verhaeren, more than any other poet of his generation, sought to express in the most truthful lyrical fashion. Although remembered mainly as a poet, Verhaeren was also a prolific playwright and a shrewd art critic. Beyond this he was nothing less than a monumental presence on the stage of Franco-Belgian literature for a quarter of a century, his name at the heart of almost all significant developments in the literary and artistic communities of Brussels and Paris.

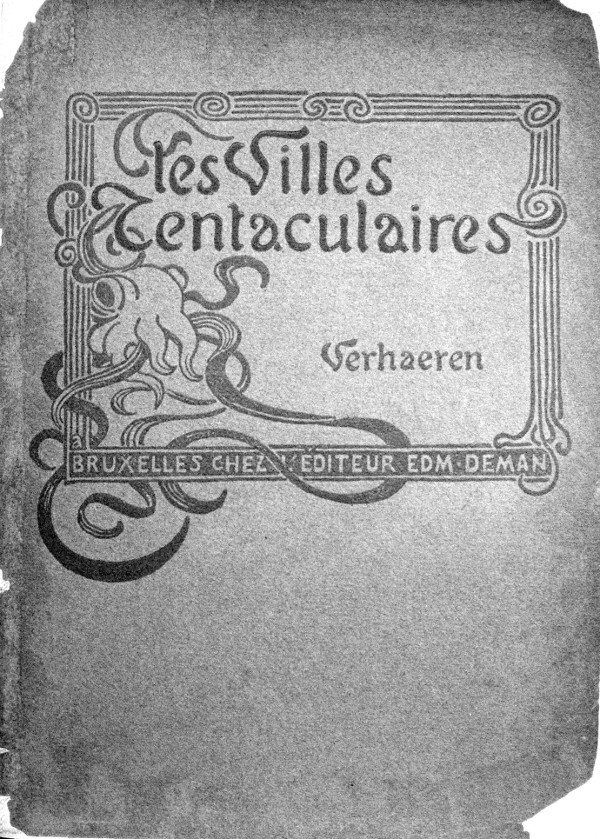

Verhaeren was an inveterate traveller and made countless extended journeys into Europe. Spain, Germany and France were his favoured destinations, although it was the teeming metropolis of London that particularly seized his imagination early on and later served as the principal cityscape for Les Villes tentaculaires [The Tentacular Towns], his landmark collection of 1895. In the years preceding the First World War, Verhaeren’s fame as a poet and a speaker snowballed and by the time of his death in 1916, he was translated into twenty languages, his name known not only across Europe but as far as Russia and South America. Verhaeren regularly filled lecture halls in the major cities of Europe, and in Germany, where his profile was enhanced by the strenuous efforts of his dedicated disciple, the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig, the sales of his poetry were considerable. Fêted by both the Belgian and English royal families, he enjoyed a certain celebrity during the early years of the war as spiritual envoy for a beleaguered Belgium. It was after delivering a speech to the exiled Belgian community in Rouen, in November 1916, that Verhaeren met his death, accidentally falling beneath the train that was to take him back to his home in Paris.

I

Emile Verhaeren was born on 21 May 1855 (the same year as his fellow poet Georges Rodenbach) in the village of Sint Amands situated on a deep bend of the River Scheldt as it winds its way towards Antwerp. These days, Sint Amands is known chiefly as the poet’s resting place – the solemn and imposing black marble tomb containing his and his wife Marthe’s remains holds a prominent place on the river bank – but Verhaeren’s memories of the village and surrounding countryside are vividly present in a number of the poems in this collection. Although he wrote his literary works in French, Verhaeren’s pride in his native Flanders and a sensitivity for its guileless, voluptuous and earthy character, infuse his work.

Emile Verhaeren was born on 21 May 1855 (the same year as his fellow poet Georges Rodenbach) in the village of Sint Amands situated on a deep bend of the River Scheldt as it winds its way towards Antwerp. These days, Sint Amands is known chiefly as the poet’s resting place – the solemn and imposing black marble tomb containing his and his wife Marthe’s remains holds a prominent place on the river bank – but Verhaeren’s memories of the village and surrounding countryside are vividly present in a number of the poems in this collection. Although he wrote his literary works in French, Verhaeren’s pride in his native Flanders and a sensitivity for its guileless, voluptuous and earthy character, infuse his work.

From 1868 to 1874, Verhaeren attended the noted College Sainte Barbe in Ghent where he became close friends with Georges Rodenbach, later to be the celebrated poet and prose painter of Bruges. Maurice Maeterlinck would also attend this college and go on to pip Verhaeren to the post by winning the Nobel Prize in 1912. Verhaeren was enrolled as a law student from 1875-1881 at the Catholic University of Louvain and although called to the bar, he turned his back on law and became prominent in an avant garde literary movement around a new magazine called La Jeune Belgique, founded in 1881 by the poet Max Waller. The poets and artists who published there declaimed a radical new society which with uncompromising zeal always put creativity first; “art for art’s sake” was its clarion call. Their heroes included Baudelaire, Gautier, Leconte de Lisle, Banville, Daudet and Flaubert. In the same year another review, L’Art moderne, which was largely concerned with criticism, appeared. Along with playwright and journalist Edmond Picard and writer and critic Octave Maus, Verhaeren was instrumental in its inception and in that of the artist movement known as ‘Les XX’ associated with it. Formed in 1883, ‘Les XX’ was a collective of twenty Belgian painters, sculptors and designers who held an annual exhibition of their art in Brussels to which the leading artists of the day were invited from Paris. Monet, Gauguin, Seurat, Cézanne and Van Gogh all made one or more visits to the Brussels exhibitions and Verhaeren formed lasting friendships with Seurat, Signac and others. In this period, Verhaeren also met the now elderly poet Paul Verlaine whose authenticity as a poet, lack of adherence to any school or trend, and odd mixture of vulnerability and pathological resilience set against an almost sacred naivety, deeply impressed Verhaeren.

Once ensconced in Brussels and with his writing career underway, Verhaeren wrote prolifically. His reviews, prefaces, essays and articles were widely published in leading journals and periodicals and his fame grew through manifold translations. But it was in L’Art moderne that he cemented his reputation as an art critic. His brilliant essay of 1908 on the artist James Ensor is still highly regarded today and one can find his name associated with key writings on Rembrandt, Rubens, Khnopff, Van Rysselberghe, Redon, Moreau, Brangwyn, Millet and many more. He was well received too by Rodin in Paris; a friendship blossomed and in 1915 the great sculptor candidly presented the poet with the plaster of an upturned face entitled ‘La Douleur’ [Pain]. In their turn, the artists reciprocated by copiously illustrating his works or providing frontispieces for his first editions; the collection Les Soirs [The Evenings, 1888] for example, carried both a frontispiece by Redon and ornamentation by Khnopff. Later works were illustrated by the reclusive Léon Spilliaert (1881-1946), whose unsettling symbolism and morbidly-imbued visions were in accord with the tenor of Verhaeren’s work. But it was the Old Masters who really shifted the foundations of Verhaeren’s imagination: Flemish Primitive painters, of course, and Rubens in Flanders, Rembrandt in Holland, Velasquez and Goya in Spain. Towering above all, however, was one Matthias Grünewald whose ‘Isenheim Altarpiece’ in Colmar, with its crucified, putrefying Christ twisted in agony at the command of a rough wooden cross, bored into the poet with an almost hallucinatory intensity of expressive possibility. For Verhaeren, Grünewald was the ultimate painterly synthesis of his own mental suffering and violently restless imagination.

Although the factions of L’Art moderne and La Jeune Belgique competed for years for the soul of Belgian literature, as the manifestation of Symbolism intensified through the mid-eighties, it was a new magazine created by critic and poet Albert Mockel, La Wallonie, that became the unrivalled voice of the Symbolist movement in Belgium. From its appearance around 1886, the Symbolist poets of France and Belgium consolidated their union, with the poet Stephane Mallarmé as their figurehead. Around the axle of his famously enriching Salons – or ‘mardis’ as they came to be known as they occurred on a Tuesday – the individual bearings of Symbolism moved, enhancing revolution. Verhaeren made frequent trips to Paris, quickly befriending Mallarmé, and finally moved there – after nearly two decades at the heart of the Brussels literary community – in 1898, ironically the same year in which both Rodenbach and Mallarmé died. He remained there until 1916, living modestly in a worker’s house in St. Cloud with his wife Marthe Massin, a watercolourist, whom he married in 1891.

In the years leading up to the First World War, Verhaeren’s presence on the European stage progressed to the point at which he became a natural torchbearer for an ideal of cultural fraternity in Europe, a resurgence of dignified artistic endeavour with a social conscience. This optimism (with socialist utopian trappings) was most clearly defined in his middle to late period work, particularly Les Forces tumultueuses [The Tumultuous Forces, 1902] and led to his being dubbed ‘the Belgian Walt Whitman’, a tag that remains to this day, but which is only partially appropriate in that Verhaeren’s work was much more raw, overwhelmingly expressive and ‘hallucinated’ than Whitman’s.

On the threshold of his fifties, and firmly established as a significant European poet and thinker, Verhaeren was routinely acclaimed with each new publication and was in great demand across the continent as a speaker. According to Stefan Zweig, however, he was unconcerned about money or glory, his passion for articulating life with uncompromising truthfulness being paramount and commanding all his energies. In the pointilliste painting ‘The Reading of Verhaeren’ (1903) by lifelong friend Théo Van Rysellberghe, we see the poet in a flame-coloured jacket with hand demonstratively raised, holding forth to a room of soberly attentive and perhaps somewhat intimidated fellow writers among whom can be identified Maeterlinck, Gide and Francis Vielé-Griffin.

Verhaeren’s reach had by now extended to the United Kingdom where a number of respected writers and critics, among them Edmund Gosse and Arthur Symons, had championed his work through the nineties. An English translation by Jethro Bithell of Stefan Zweig’s reverential biography, Emile Verhaeren (1910), appeared with Constable in 1914. Aldous Huxley wrote a witty and insightful essay on Verhaeren in his collection On the Margin (1923) followed, in 1926, by the rather academic and now somewhat dated study (Verhaeren: a Study in the Development of His Art and Ideas) by Percy Mansell Jones. In the 1950s an English scholar named Beatrice Worthing produced a highly-informed, in-depth biography of Verhaeren which, never having found a publisher in the UK, only received the recognition it deserved when it was translated into French and finally published, to considerable acclaim, by Verhaeren’s old French publisher Le Mercure de France in 1992. More recently, a comprehensive modern biography, Verhaeren: biographie d’une œuvre by Jacques Marx appeared in Belgium in 1996. In late 2012, Emile Verhaeren, Vlaamse dichter voor Europa, a new biography in Dutch by Paul Servaes, ex-curator of the Verhaeren Museum in Sint Amands, was published and launched at the Museum. The most influential figure for Verhaeren’s reputation in England during his lifetime was the critic and translator Edward Osmans, who invited the poet to England on several occasions to stay with him and his family, using his influence and contacts to further his name. But despite their interest and the passionate admiration of certain individuals, the English struggled to assess Verhaeren conclusively, seeing him first as a Zola-inspired realist, then as a ‘decadent’ poet of the nineties, then as the wild progeny of Victor Hugo and Whitman.

Verhaeren’s reach had by now extended to the United Kingdom where a number of respected writers and critics, among them Edmund Gosse and Arthur Symons, had championed his work through the nineties. An English translation by Jethro Bithell of Stefan Zweig’s reverential biography, Emile Verhaeren (1910), appeared with Constable in 1914. Aldous Huxley wrote a witty and insightful essay on Verhaeren in his collection On the Margin (1923) followed, in 1926, by the rather academic and now somewhat dated study (Verhaeren: a Study in the Development of His Art and Ideas) by Percy Mansell Jones. In the 1950s an English scholar named Beatrice Worthing produced a highly-informed, in-depth biography of Verhaeren which, never having found a publisher in the UK, only received the recognition it deserved when it was translated into French and finally published, to considerable acclaim, by Verhaeren’s old French publisher Le Mercure de France in 1992. More recently, a comprehensive modern biography, Verhaeren: biographie d’une œuvre by Jacques Marx appeared in Belgium in 1996. In late 2012, Emile Verhaeren, Vlaamse dichter voor Europa, a new biography in Dutch by Paul Servaes, ex-curator of the Verhaeren Museum in Sint Amands, was published and launched at the Museum. The most influential figure for Verhaeren’s reputation in England during his lifetime was the critic and translator Edward Osmans, who invited the poet to England on several occasions to stay with him and his family, using his influence and contacts to further his name. But despite their interest and the passionate admiration of certain individuals, the English struggled to assess Verhaeren conclusively, seeing him first as a Zola-inspired realist, then as a ‘decadent’ poet of the nineties, then as the wild progeny of Victor Hugo and Whitman.

Russia, on the other hand, gearing up for revolution, was poised to applaud Verhaeren’s achievements. From around 1906, with the support of the poet Brioussov, he was widely published in reviews; his urgent spiritual manifestos seemed to strike a particular chord with the Russians as they had previously with the Germans. Even the great poet Alexander Blok attempted to translate him and Anna Akhmatova evokes his name in her memories of Blok. And in 1916, when Verhaeren died, Mayakovsky alluded to the cruelty of his sudden absence in his collection Darkness:

One after another the greats pass on

colossus after colossus…

today above Verhaeren the skies are furious.

Closer to home, André Gide wrote that Verhaeren was the most accomplished poet writing in French at the turn of the century, declaiming: “You are our only epic poet and I hold you in an esteem above all others.” For the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, Verhaeren was a senior figure, a master in the same vein as Rodin, a living example of artistic integrity and uncompromising creative labour. Since arriving in Paris in 1902, Rilke had made the French capital the necessary anchorage between his disparate European sojourns and was to become as regular a visitor at St. Cloud as he was at Meudon. Rilke’s respect and admiration for Verhaeren was like that of Stefan Zweig, profound and long-lasting. The scrupulously respectful messages and dedications he left in books given to the older poet, struggle to express the devotion he felt: “To my dear and great Verhaeren, your Rilke. St. Cloud 11th January, 1909” or, as he wrote, simply, in a copy of the Cornet, “For Emile Verhaeren, intensely… Rilke”. When he was completing his famous Elegies and Sonnets to Orpheus, Rilke wrote a short prose text, Letter of a Young Worker, addressed to a mysterious ‘Monsieur V’ whose identity was, in fact, Verhaeren. Following the First World War and Verhaeren’s death, Rilke read his later collections avidly and in his letters is seen to recommend them to a number of friends. In La Multiple splendeur [The Multiple Splendour, 1906], Les Forces tumultueuses and, perhaps most pertinently, in the posthumous collection Les Flammes hautes [The High Flames, 1917], Rilke found an inflexible will and energy in truth-seeking that seemed in alignment with the approach to poetry which he himself had so patiently been edging towards. And although Verhaeren was evidently a very different poet to the more mysterious and introspective Rilke, his world-affirming objectivity and unquenchable life force served to energize his perennially self-questioning friend.

It was Stefan Zweig who took it upon himself to forge Verhaeren’s reputation in Germany and the correspondence between the two men shows the inexhaustible energy expended in the fulfilment of this task. Zweig felt Verhaeren’s poetic impulse keenly and recognised the sacrifice of those interminable stretches of solitude in hostile environments that gave rise to great poems. He describes in his memoirs, for example, how Verhaeren would travel around London: “Often he remained for hours on the top deck of an omnibus better to see the throng, eyes closed better to feel this muffled drone penetrate into him, like the rustling of a forest…”. Zweig would often visit the Verhaerens in Paris or, for five consecutive summers, joined them in Caillou-qui-bique in southern Belgium close to the French border where Verhaeren retreated to his remote country cottage during the seasonal break to experience the simplicity of a rural idyll as yet untouched by modernity. (It was the countryside around Caillou which informed much of Verhaeren’s later work and crucially the series of love poems he dedicated to Marthe.) The two men unknowingly parted for the last time in the unsettling summer of 1914 when, as a European war loomed, Zweig was obliged to leave Belgium abruptly on the last Orient Express bound for Germany:

It was in the spring, that terrible spring of 1914. The horrendous year had begun. Quite gently, peacefully it advanced and ripened into the summer. We were due to meet. I would spend the month of August with Verhaeren, but I had already been in Belgium since July to spend three weeks by the sea. En route, I stopped off for a day in Brussels and my first priority as soon as I arrived was to go and see Verhaeren at his friend Montald’s house. A tram took me along a wide avenue, then through open fields, leading me to Woluwe where I duly found Verhaeren with Montald, who had just finished his portrait, the last one to be made! What joy to see him there! We spoke of his last works, of his ‘Flammes hautes’, whose last verses he read aloud to me, of his drama ‘Les Aubes’, which he was revising for Reinhardt; we spoke of friends and of the summer which would bring us fresh joys and new pleasures. We only bade a brief farewell, since we would be seeing each other soon in his country cottage. To say goodbye, he clasped me in his arms. I should arrive on 2nd August and he shouted after me one more time: the 2nd, the 2nd of August! Alas, little did we know the significance of the date we had so casually arranged in that moment. The tram crossed fields bathed with summer. I watched him for a long time, waving to me by Montald’s side, until I could see nothing more…4

With the outbreak of war in the late summer of 1914, the dream of a cultural European union pursued so ardently by Verhaeren, Zweig, Rolland and their circle was brutally swept aside by the pandemic of nationalist fervour and politically orchestrated hatred between foes. The wilful destruction of ancient towns such as Louvain, of priceless libraries and works of art and the slaughter of innocents by German forces on Belgian soil had a devastating effect on the acutely sensitive Verhaeren. For him, all relations with Germany, literary or otherwise, were now at an end. Faced with atrocities on such a scale, he allowed himself, in spite of his anti-nationalist convictions, to be infected by hatred for the foe and began to write vitriolic texts against Germany – ironically the country that before this outbreak of barbarism had seen the greatest support for his poetry – and German culture. The switch was extreme, for even as war fever grew in the late summer of 1914, Zweig, Rilke and their Insel publisher, Kippenberg, had met in a restaurant in Paris to flesh out the plan for a Collected Works of Verhaeren in German and were already in the process of farming out the works to various translators (Zweig himself was apparently to tackle La Multiple splendeur). Then war broke out and the project was abandoned, never to be resumed. Zweig, trapped behind impassable frontiers, asked for news of Verhaeren. But the line of communication had gone dead. Verhaeren’s fury at Germany’s scorched earth policy in Belgium took the form of a book called La Belqique sanglante [Belgium Bleeding], a visceral anti-German polemic quickly translated into English and published first in The Observer in 1914, then in book form in 1915. Even in a letter thanking his Russian hosts after a conference in Moscow in 1915, Verhaeren took the opportunity of warmly praising Russian culture while denouncing its German counterpart. A collection of poetry expressing similarly anti-teutonic sentiments, Les Ailes rouges de la guerre [The Red Wings of War], was published in 1916 but by then Verhaeren’s unbridled animosity was giving way to a more rationally balanced position, and that same year he began to send out feelers to old friends across the frontier, full of contrition for his earlier blind support of this ‘lamentable division of nations’.

This tentative drawing back of the Germanic satellites into his orbit was rudely terminated by Verhaeren’s death in Rouen and Zweig was never to see the reunion he so craved. His reverence for Verhaeren never faltered and with his untimely death, took on an almost messianic property. In Errinerungen an Emile Verhaeren [Memories of Emile Verhaeren], published in Vienna in 1917, he recalled the emotion of their early encounter and revealed the essence of Verhaeren’s beguiling character:

For the first time I felt the grasp of his vigorous hand, for the first time met his clear kindly glance. He arrived as he always did brimming over with enthusiasm and the experiences of the day. As he fell to his meal he began to talk…With the first word he went straight to the essence of people, because he was himself completely open, open to everything new, rejecting nothing, ready for every individual… it seemed as if he projected his whole being towards you. He knew as yet nothing of me, but was already full of gratitude for my inclination, already he offered me his trust simply because he heard I was close to his work. And in spite of myself, all shyness faded before the stormy onslaught of his being. I felt myself free, as never before, in the face of this unknown, open man. His gaze, strong, steely and clear, unlocked my heart.

It was on 27 November 1916 that a weary Verhaeren, having given a rousing speech to appreciative Belgian exiles in Rouen, fell beneath the train for Paris in an attempt to board it prematurely to secure a seat. Fatally injured, he died shortly afterwards on the platform, reportedly (though falsely, it is now claimed) uttering the words: “Je meurs, ma femme, ma patrie…”. The shock of the sudden and brutal demise of this figurehead, chosen emissary of the King of Belgium, the nation’s poet, was profound and the mourning heartfelt across Europe, including England. Verhaeren’s body needed to be brought back to Flanders to his chosen resting place beside the Scheldt at Sint Amands, but in wartime such a journey was complicated and dangerous. Marthe and the painter Théo Van Rysselberghe, however, were determined to get Verhaeren home and so the extraordinary cortège with its attendant mourners commenced its journey across northern France, through hostile military terrain and across the border into Belgium.

In the rash of memorials in the wake of Verhaeren’s death, one held at the Académie Française in Paris chose the great French poet Paul Valéry as its speaker. He said of his Belgian counterpart:

This is a great drama, gentlemen, we are living through, but this drama has found its poet. The competing themes of this life, between what has been and what might be, the disruption of nature and these deranged movements of men, found in Verhaeren their introduction, their master, their unique song. Through him our civilisation will have received the eminent dignity of lyrical expression.

II

From the very beginning until the last decade or so of his life, Verhaeren’s poetry was in a state of evolution and flux. Unlike Rodenbach (whose poems are really one long meditation with Bruges and the dying canal towns of Flanders at their centre), or the Austrian poet Georg Trakl (1887-1914, whose subject range is narrow but of impressive visionary depth), Verhaeren’s œuvre proceeds in a series of broad steps splashed with the gore of grief and the nectar of impetuous joy; existential challenges are forged from the paroxysm of crisis, cosmological ideals, a burgeoning socialism and the decisive upheavals in his personal life. Verhaeren remains robust and ritually enthusiastic, even in despair, and when in this state, he is able to record and comment on it from within its deepest recesses. The critic and poet Albert Mockel, who wrote an early biography of Verhaeren, believed that he possessed “a magic power to hypnotise himself”. His vital and expressively fluid poetry was later to act like cool oil on the overtaxed alexandrines of French poetry, and once he had turned his back on corrosive despair and suicidal impulses, his star was always directed towards life and its celebration without losing sight of its tragic propensity for pain and loss.

From the very beginning until the last decade or so of his life, Verhaeren’s poetry was in a state of evolution and flux. Unlike Rodenbach (whose poems are really one long meditation with Bruges and the dying canal towns of Flanders at their centre), or the Austrian poet Georg Trakl (1887-1914, whose subject range is narrow but of impressive visionary depth), Verhaeren’s œuvre proceeds in a series of broad steps splashed with the gore of grief and the nectar of impetuous joy; existential challenges are forged from the paroxysm of crisis, cosmological ideals, a burgeoning socialism and the decisive upheavals in his personal life. Verhaeren remains robust and ritually enthusiastic, even in despair, and when in this state, he is able to record and comment on it from within its deepest recesses. The critic and poet Albert Mockel, who wrote an early biography of Verhaeren, believed that he possessed “a magic power to hypnotise himself”. His vital and expressively fluid poetry was later to act like cool oil on the overtaxed alexandrines of French poetry, and once he had turned his back on corrosive despair and suicidal impulses, his star was always directed towards life and its celebration without losing sight of its tragic propensity for pain and loss.

Verhaeren’s first collection, Les Flamandes [The Flemish Women, 1883], caused a minor scandal in staunchly Catholic Sint Amands. With its lusty Rubensesque content, it laid on a feast of earthy Flemish life or, as Zweig described it in his biography, “teeming with the exuberance of Rabelais”. The poet’s religiously pious family, appalled at the book’s reception and fearing loss of face in the village, tried to prevent the printing of further copies but Verhaeren had already caused a stir; he had impressed the avant garde beyond the provinces, even though he was still something of an onlooker, an “energetic colourist” whose “wild stallions”, as Zweig put it, were “still trotting along in the harness of the alexandrine.”

The following collection was intriguing and perhaps unexpected. Les Moines [The Monks, 1886] was a step aside into a more rigid formal style and consisted of poems that Mockel described as “surrounded by a cold Parnassian light which turns them into an anonymous work, in spite of the poet’s mark punched in many places over their surface.” Childhood memories of the monastery at nearby Bornhem and the romantic mystery it evoked feed into an idealised view of monks, hair-shirted martyrs emerging from the ruins of history as symbols of a religious idealism. To get into character, Verhaeren even donned a monk’s habit, wrote standing at a lectern and entered the monastery of Forges near Chimay for a few weeks to learn about the life there. Chilled by the austere conditions, however, he soon fled.

The following few years of Verhaeren’s life, the late eighties, are marked by extreme mental torment and attendant ill-health, a favourable consequence of which was a major burst of poetic creativity. It was time for a rejection of the old order and a necessary tearing through into the modern, experimentation with free verse enabling his imaginative power to exploit his experience to the full – ‘breakdown and breakthrough’ one might term this period. During long periods of travel to Germany, Spain, Paris and London, Verhaeren allows himself to be overwhelmed by raw and exotic sensations, his morbid sensitivity further heightened by a strong infusion of Schopenhauer’s philosophy. The death of his parents and estrangement from Catholicism leave his nerves raw. His mental state deteriorates as he endures self-imposed solitude in foreign places where, as a genuine flâneur, he welcomes the insatiable energy and anonymity of the crowd. He suffers digestive problems and, like Nietzsche, is sucked into a fetishist mania of physical self-regard caused by bad diet, alienation and nervous exhaustion. He travels again and again to London, lured by the febrile energy of the swollen metropolis and, on the very lip of the abyss, he manages to claw out three volumes of poetry. As Valéry put it: “Verhaeren returned from the hell of his heart and thought, bearer of the terrifying hides of the enemy that he had felled within himself.” These volumes of bleak and often tortured poetry are generally cited by critics and readers today as amongst Verhaeren’s strongest and most resilient work and stand alongside Maeterlinck’s Serres chaudes [Hothouses, 1889] as the most important verses by Belgian hands to come out of that decade.

First came Les Soirs [The Evenings, 1887] followed by Les Debacles [The Debacles, 1888] and finally Les Flambeaux noirs [The Black Flames, 1891]; these three related collections became known later as La Trilogie noire, a label that has stuck. As Verhaeren later explained:

They correspond to a state of physical sickness that I went through and where I worshipped pain for itself, in a kind of rage and savagery. Les Soirs sets the scene of a being who cries out, Les Debacles are the cry itself, Les Flambeaux noirs the reflection of the pain on general ideas which plague the afflicted one and which he deforms through his sickness and his abnormal personality.

He then admitted: “These three books have never been properly understood.” What exactly he meant by this remains obscure, but what can be understood is that poems like ‘Fatal Flower’ and ‘The Revolt’ cradle an invocation to a poet’s interior suffering worthy of Baudelaire. In ‘Fatal Flower’ for example, Verhaeren declares emphatically: “I want to stride towards madness and suns…” (p. 45) and in the last lines of ‘The Revolt’ the tension spills into a horrifying prospect which somehow recalls the acuminous anxiety of Poe or a frenzied scene from a Goya etching in the Disasters of War series:

The hour has come – yonder sounds the alarm;

against my door the rifle butts hammer

to kill, to be killed – what does it matter!

(‘The Revolt’, p. 53)

One also sees the earliest examples of Verhaeren’s delirious affirmations of the overpowering nature of life reaching through the gloom, as in the poem ‘To Die’:

To die! Like overgrown flowers, to die!

Too massive and too gigantic for life

(p. 41)

while other poems, such as ‘The Darkness’, ‘The Windmill’ and ‘The Frost’ mirror, in monochrome, the poet’s depressive affliction. Here, in ‘The Frost’, Verhaeren transmits the essence of a melancholy Flanders landscape held fast in the wires of an eternal winter:

This evening, a vast open sky, abstract, supernatural,

cold with stars, infinitely inaccessible…

…and nothing to disturb the primal process,

this reign of snow, bitter and corrosive.

(‘The Frost’, p. 43)

Les Flambeaux noirs also contains the poem ‘The Town’, an extract of which is included in this volume, which looks ahead to a greater work to come – “The old dream is dead, the new is forged…” (‘The Soul of the Town’, p. 89).

After this time of crisis, Verhaeren entered a new phase in his personal life and his poetry. Following a prolonged courtship, he married Marthe Massin who was to dedicate her life to supporting him. Their love for each other lasted until Verhaeren’s death in Rouen – and beyond, for Marthe never really recovered from her loss. Saved from mental collapse at the eleventh hour by Marthe, Verhaeren began to produce a series of works which moved away from the tormented and fiercely subjective, towards nature and the rapidly changing industrialized world at large. In Les Campagnes hallucinées [The Hallucinated Countryside, 1893] and the masterwork which followed in 1895, Les Villes tentaculaires, declamation rather than meditation germinates, the epic flexes its muscles and Hugolian words such as ‘infinite’, ‘monstrous’, ‘gigantic’ and ‘eternal’ appear with ever greater regularity, so much so that Aldous Huxley wryly observed that they “tend to mislay their power”. Verhaeren’s principal concerns, however, are the flood of people leaving the land for the cities, and the encroachment of these cities on the rural landscape he grew up in, a representation of which – in the rain, the snow, the wind and populated by rural labourers (including the ferryman, subject of one of Verhaeren’s best-loved poems) – we are treated to in his next collection, Les Villages illusoires [The Illusory Villages, 1895]. Les Campagnes hallucinées presents a canvas of what the towns leave behind in the rural heartland – rats intent on devouring, wandering madmen and idiot stragglers weaving between the dykes and ponds of stagnant water, exemplified by the wonderfully observed poem ‘The Beggars’. The poem ‘The Town’ (in which we see the town as vampirical devourer of the countryside) looks ahead to the ambitious and monumental Les Villes tentaculaires of 1895. Here Verhaeren’s observations of industry and its unremitting, indifferent energy and toxic cacophony, of mercantilism and its accompanying vices, of the multitudinous population of the city, all consolidate in mighty poems which fall like Thor’s hammer, such as ‘The Soul of the Town’ and ‘The Plain’. While we have had glimpses of the sprawling gin-soaked London of carnality and scoured souls in earlier shorter poems such as ‘London’ from Les Soirs, and ‘Shady Quarter’ published posthumously, here the plaint is on a more grandiose scale, the cry more urgent, unflinching:

After this time of crisis, Verhaeren entered a new phase in his personal life and his poetry. Following a prolonged courtship, he married Marthe Massin who was to dedicate her life to supporting him. Their love for each other lasted until Verhaeren’s death in Rouen – and beyond, for Marthe never really recovered from her loss. Saved from mental collapse at the eleventh hour by Marthe, Verhaeren began to produce a series of works which moved away from the tormented and fiercely subjective, towards nature and the rapidly changing industrialized world at large. In Les Campagnes hallucinées [The Hallucinated Countryside, 1893] and the masterwork which followed in 1895, Les Villes tentaculaires, declamation rather than meditation germinates, the epic flexes its muscles and Hugolian words such as ‘infinite’, ‘monstrous’, ‘gigantic’ and ‘eternal’ appear with ever greater regularity, so much so that Aldous Huxley wryly observed that they “tend to mislay their power”. Verhaeren’s principal concerns, however, are the flood of people leaving the land for the cities, and the encroachment of these cities on the rural landscape he grew up in, a representation of which – in the rain, the snow, the wind and populated by rural labourers (including the ferryman, subject of one of Verhaeren’s best-loved poems) – we are treated to in his next collection, Les Villages illusoires [The Illusory Villages, 1895]. Les Campagnes hallucinées presents a canvas of what the towns leave behind in the rural heartland – rats intent on devouring, wandering madmen and idiot stragglers weaving between the dykes and ponds of stagnant water, exemplified by the wonderfully observed poem ‘The Beggars’. The poem ‘The Town’ (in which we see the town as vampirical devourer of the countryside) looks ahead to the ambitious and monumental Les Villes tentaculaires of 1895. Here Verhaeren’s observations of industry and its unremitting, indifferent energy and toxic cacophony, of mercantilism and its accompanying vices, of the multitudinous population of the city, all consolidate in mighty poems which fall like Thor’s hammer, such as ‘The Soul of the Town’ and ‘The Plain’. While we have had glimpses of the sprawling gin-soaked London of carnality and scoured souls in earlier shorter poems such as ‘London’ from Les Soirs, and ‘Shady Quarter’ published posthumously, here the plaint is on a more grandiose scale, the cry more urgent, unflinching:

Unimaginable and criminal

the arms of hyperbolic machines

scything down the evangelic corn…

(‘The Plain’, p. 85)

Verhaeren’s new industrial cities were described by Valéry as “tentacled creatures whose body grows interminably, with unsettling activity, uncoordinated interior exchanges, incessant production of ideas, vices, luxury, political and artistic sensibilities that breed there, demanding a frenzied consuming of people, of living and thinking substance which they absorb and transform without rest.” Surely there could hardly be a more accurate picture of the mega-urban metropolis of today. Although Verhaeren was aghast at the new industry’s obliteration of the rural landscape, he nevertheless committed himself to a precarious optimism for the future, which largely explains his notable absence in the literary canon of post-war decades. Verhaeren determined to see in the infectious energies and rhythms of the new town a crucible for spiritual transformation or transcendence, a figurative communal energy channelled through heroic individual endeavour raising the consciousness of mankind.

In its visionary convulsion, Les Villes tentaculaires looks forward to the Expressionist poetry of the city, most notably by the Berlin poet Georg Heym, with his powerfully expressive poems such as ‘Demons of the Cities’ and ‘God of the Town’. Elements of Verhaeren’s vision are also expressed most forcibly by Heym’s contemporary, the painter Ludwig Meidner in his ‘Apocalyptic Landscape’ series of 1912. Thanks to the efforts of Zweig and others, Heym would have read Verhaeren’s works in translation in the first decade of the new century and have been influenced by his example. With imposing works like Les Villes tentaculaires, Verhaeren shows himself as a true pioneer of Modernism, as his form of life affirming, expressionistic poetry leads into the war-inspired apocalyptic incendiaries of Expressionism proper, and through to Eliot’s The Waste Land a decade or so later. Verhaeren’s yearning for humanity to somehow walk upright out of an industrial inferno that appeared to be consuming it, led almost inevitably towards socialism, which burgeoned as Zweig poetically put it “like a red blood drop upon his morbidly pallid poems”. In the rapidly changing climate of the new century, Verhaeren’s vision takes on the universality, the cosmic breathlessness for which he became known, giving rise to bold and dynamic poems that proclaim a transformation of values with varying degrees of success. His explicit fascination for humanity and its trajectory – what Robert Vivier called Verhaeren’s optimistic ‘mondialisme’ or world view, commences with Les Visages de la vie [The Faces of Life, 1899], and runs through the subsequent collections Les Forces tumultueuses, La Multiple splendeur, Les Rythmes souverains [The Sovereign Rhythms, 1910] and even into the posthumously published Les Flammes hautes. As Zweig explains in his biography, this final collection brings together a network of forces apparently separated from one another which are now revealed as having an ultimate cohesion: “In all manifestations of material life, he discovers the eternal forces: drunkenness, energy, triumph, joy, error, expectation, illusion. And these forces, or rather these forms of an essential force, animate all his poetry.”

In its visionary convulsion, Les Villes tentaculaires looks forward to the Expressionist poetry of the city, most notably by the Berlin poet Georg Heym, with his powerfully expressive poems such as ‘Demons of the Cities’ and ‘God of the Town’. Elements of Verhaeren’s vision are also expressed most forcibly by Heym’s contemporary, the painter Ludwig Meidner in his ‘Apocalyptic Landscape’ series of 1912. Thanks to the efforts of Zweig and others, Heym would have read Verhaeren’s works in translation in the first decade of the new century and have been influenced by his example. With imposing works like Les Villes tentaculaires, Verhaeren shows himself as a true pioneer of Modernism, as his form of life affirming, expressionistic poetry leads into the war-inspired apocalyptic incendiaries of Expressionism proper, and through to Eliot’s The Waste Land a decade or so later. Verhaeren’s yearning for humanity to somehow walk upright out of an industrial inferno that appeared to be consuming it, led almost inevitably towards socialism, which burgeoned as Zweig poetically put it “like a red blood drop upon his morbidly pallid poems”. In the rapidly changing climate of the new century, Verhaeren’s vision takes on the universality, the cosmic breathlessness for which he became known, giving rise to bold and dynamic poems that proclaim a transformation of values with varying degrees of success. His explicit fascination for humanity and its trajectory – what Robert Vivier called Verhaeren’s optimistic ‘mondialisme’ or world view, commences with Les Visages de la vie [The Faces of Life, 1899], and runs through the subsequent collections Les Forces tumultueuses, La Multiple splendeur, Les Rythmes souverains [The Sovereign Rhythms, 1910] and even into the posthumously published Les Flammes hautes. As Zweig explains in his biography, this final collection brings together a network of forces apparently separated from one another which are now revealed as having an ultimate cohesion: “In all manifestations of material life, he discovers the eternal forces: drunkenness, energy, triumph, joy, error, expectation, illusion. And these forces, or rather these forms of an essential force, animate all his poetry.”

There is, however, an incongruity in Verhaeren’s thought which both redeems him in an existential sense and also distorts the clarity of his vision. Verhaeren was acutely sensitive to mortality, but his yearning for human breakthrough rather than breakdown, and his will to transcend eternal human folly through creative energy, despite the poisoning effects, both spiritual and physical, of the onslaught of industrialism, prove fascinating, given the threshold to apocalyptic totalitarianism and holocaust he was unknowingly standing on. It is these unfortunate contradictions in his work that led to his poetry being neglected after the necessary radical recalibration of civilization following the First World War.

But looking back from a century later, it is hard not to admire Verhaeren’s passion for life and protean dedication to all that grows and gains in strength. In his epic poem ‘The Tree’, for example, he undergoes a kind of inner transmogrification as his almost untenable enthusiasm and love for the tree fuse within him. As Zweig asserts, Verhaeren does not so much feel for his chosen subject in nature as actually becomes part of it; there is always an organic progression in his work, a slow and sure development which increases in strength as does a tree with each successive ring.

With the series Toute la Flandre [All Flanders] of 1908, we observe a more nostalgic, resigned and ageing Verhaeren irresistibly combing the natural world around him. Here are some of his most convincing non-epic works, intimate pieces replete with finely-observed detail and an impressionistic quality. Poems about life amongst the Flanders dunes, the sudden mood changes of the sea, the plight of the poor but proud fishermen are all particularly moving. They present a document of a rural coastal life lived in constant fear of loss at sea, a hard life lived close to nature, but an authentic one long since vanished under the monolithic concrete edifices of property developers:

Yet nevertheless the tiny lights

still keep watch from the cottages;

scattered amongst the dark enclosures

like crumbs of hope.

(‘The Danger’, p. 119)

In the collection dedicated to Arthur Symons, Les Villes à pignons [The Gabled Towns, 1909] there are a number of dark-hued, haunting poems evoking the abandoned ports and the quays of the Flanders canal towns, the last saline breath of the dead cities of Bruges, Courtrai, Oudenarde, or even the somewhat healthier lungs of Antwerp. Not surprisingly these poems seem to drift closer to the territory of Rodenbach, wounds of a once-animated place with their melancholy dressings. In the poem ‘The Ship’ from Les Rhythmes souverains [The Sovereign Rhythms], we find Verhaeren steady at the helm of his mature lyrical gift, producing a Conrad-like narrative to open the poem whose imagery seems effortlessly conjured from experience:

We were advancing, calmly, beneath the stars;

the oblique moon wandered around the bright craft,

and the white terracing of spars and sails

laid upon the ocean its giant shadow.

The cold purity of blazing night

glinted in space and quivered on the water;

you could see the Great Bear and Perseus

high above, as if in a dazzling shadow circus.

(‘The Ship’, p. 127)

One of the biggest surprises in Verhaeren’s work viewed as a whole is the trilogy of extraordinary poems he wrote to express his especially deep love for Marthe. These much-admired ‘Hours’ poems occur at intervals from 1896 to 1911 and have been placed chronologically in the text of this collection. Perhaps more than any of his other work, these intimate love poems for Marthe seem as fresh as when they were penned. One can almost smell the plants and soil after a rain shower, touch the trellises of fruit and feel the breeze across the plot at Caillou-qui-bique on reading them. Not only are they moving in their honest unembroidered state, stark and unencumbered by any portentousness or sentimentality, but they harbour a fusing of nature (in this case the isolated cottage garden at Caillou) and the human condition:

And that I feel, before the coffin lid is nailed down,

on the pure white bed our hands enjoin

and beside my brow upon the pale cushions,

for a supreme moment your cheek rest.

(‘The Evening Hours, XXVI’, p. 131)

A few other poems seem to signal fraternally to those in the ‘Hours’ series. ‘The Storm’ from Les Blés mouvants [The Moving Corn, 1912) recalls an incident in an orchard at the onset of a storm. This simple everyday moment becomes poetry in the hands of Verhaeren, the open-hearted onlooker who, in communion with the universal soul of things, endows orchard, fruit and grasses with a life within and yet beyond their own reality. Here, in a deceptively simple poem, one finds both the affirmation of physical elemental life and of ‘elsewhere’ in the image of the “laughing fruit” after the storm has passed, a symbol perhaps for Verhaeren’s own existence.