Chapter 21

At Sea

May 1989

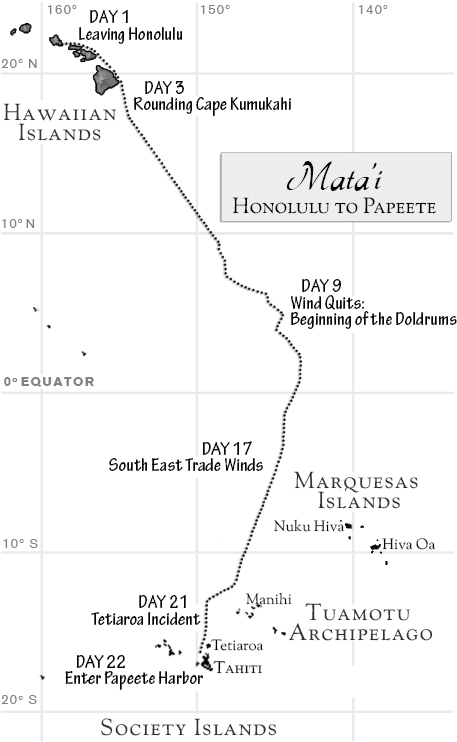

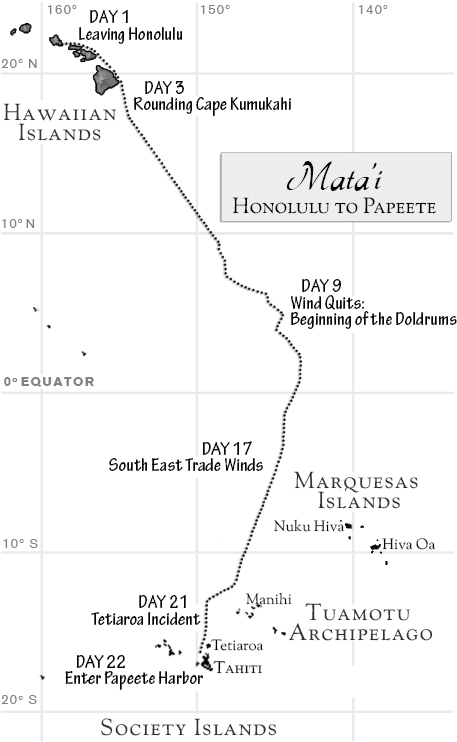

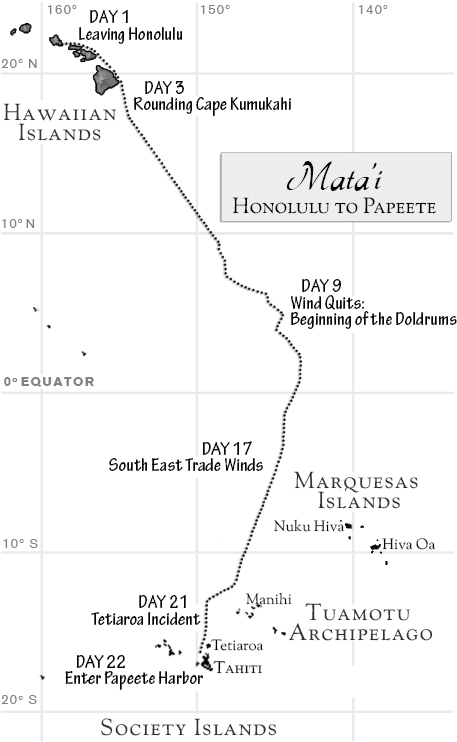

It took almost two days to reach the Big Island of Hawaii, forty hours of close-hauled sailing with twenty-knot trade winds and fourteen-foot seas. The Aires hadn’t worked since the first night out when Larry, frustrated by what he believed to be a flawed piece of equipment, began to blame Jason for the violent weather. Larry had a mind that made those bazar connections seem almost rational.

Those first couple of days set the tone for the whole trip. David was at the helm when the sun rose directly over Mata‘i’s bow on that second morning. The yacht was approaching the Alenuihaha Channel separating Maui from the Big Island. They were a few points off the wind and Larry had taken one of the reefs from the mainsail. Mata‘i had a fine sea-kindly motion as she rose to the top of the swell, splitting its top before riding down into the trough and sending heavy spray back toward the cockpit, drenching the foresail and then rising again.

Larry came topside and stood behind David for a few moments before David realized he was there. David was in the rhythm of the boat, playing with every micro change in wind direction and velocity, keeping the boat at speed while playing the swell. It was a dance, Mata‘i was his lady, and the sea and the wind were his orchestra.

“You handle her quite well,” Larry said, startling him. “Most racing skippers I know like to beat the shit out of a boat in this kind of weather.” David didn’t answer as Larry went forward into the salon. He was driving Mata‘i the same way he would one of the ocean racers that had made his reputation as a helmsman in the international regatta circuits.

Larry came back with a hand held direction finder and took bearings off various landmarks along the windward coast of Maui.

Jason came up on deck and stumbled back to the leeward mizzen shrouds to piss over the side.

Byron came up with two cups of coffee and gave one to David. “Are we going to Mexico or Tahiti? I thought we were supposed to sail south, not east.”

“We need to make our easting. I’d rather take it now than have to beat our way into Papeete,” Larry informed his brother.

“You’re not going to duck through that channel ahead and give us a couple of days’ smooth sailing?” Byron said referring to the channel between Maui and Hawaii Island.

Larry looked at Byron as if he was an idiot.

That night, after a monotonous day sailing down the windward coast of Maui, Mata‘i had left Hana astern and was half way across the Alenuihaha Channel, considered to be one of the roughest on the planet, bound for the Kohala coast of the Big Island. David was back at the helm and he kept his eye on the knot meter. They were still too close-hauled to surf the swells, but their sailing angle had improved the further east they went. Still, the ride was not very smooth. Jason was in the salon cleaning the dinner dishes—a duty only he and David shared—and the diesel had been idling since sunset. Larry insisted that the batteries be charged every night. He and Byron lounged in the cockpit, sipping brandy under a dark and cloudy sky.

“I was in the 1978 Newport-Bermuda race,” Byron said. “Were you with me on that one, Larry? No, I think it was just my first wife and her brothers. We partied all the way down. Can’t remember where we placed. But you took the ‘Lighthouse Trophy,’” he said to David.

“We had a great crew from the Brown sailing team, and a very nice old Cal 40 loaned to us by an alumnus. He wanted his boat in the race and came along for the ride. I guess it paid off,” David said.

“Why the East Coast?” Larry said. “I thought you were a California boy like Jason.”

“Just the way things worked out. Two weeks ago I was staying at a fleabag hotel in Barcelona getting my fill of Gaudi.”

Jason came up from below and stood in the companionway. “Can we turn off the diesel yet? It’s an oven down here.”

“What’s the reading on the batteries?” Larry said, getting up.

“Both banks one hundred percent.”

Larry checked the engine instruments tucked under one of the lounge seats. “Fuck.” He tapped on the instrument and then rushed below, pulling Jason into the cockpit so he could get by. “Byron, kill the motor!” he yelled from below. “Shit. Shit. Shit. Jason, get down here!”

Jason glanced at the instruments. “She’s overheating,” then he disappeared below.

Larry ordered Jason into the scorching engine compartment to discover the problem while he waited in the companionway where the air was fresh. The Volvo was cooled by a heat exchanger, which pumped in seawater to chill the antifreeze running through the engine. Jason discovered a crack in the heat exchanger. Besides being an oven, the engine compartment was cramped. Every time the boat lurched Jason fell against something hot and burned himself. Eventually he sealed the crack with duct tape, which stopped the leak until a more thorough repair could be made when the seas calmed down. After some time below, he came up for air and reported the situation to Larry.

David and Byron thought Jason had been resourceful and had solved the immediate problem, but Larry was furious. “Who told you to do a fucking makeshift repair? Work done on Mata‘i is to be done properly at the moment. I don’t care what the seas are like. If you put off something like this, or jerry-rig it, you’ll pay for it down the road.” He made Jason go below, pull the tape off the exchanger, cut a length of copper, and properly solder it to make the repair permanent.

Larry took over the helm and seemed proud of his decision. David noticed that Larry couldn’t steer that well. He kept luffing the jib, causing the bow to fall off a swell with a crash rather than slide over the waves as David had done. David looked at Byron, and Byron just shrugged. Was Larry doing that on purpose to make Jason sick, to punish him? Would his pride let him do that, or was he just mean? Byron nodded to David, reminding him what he’d said before they departed: Larry wasn’t the sailor he thought he was.

“You’re not worried that he’ll make a mess of the repair?” Byron finally asked Larry.

“If he does, he’ll do it again. The boy’s got to learn how to deal with things when they need to be dealt with.”

The next day Larry set a course a few more degrees south of east, and Jason and David shook out the remaining reefs in the sails. Mata‘i fell into a beam reach and showed her speed. Larry was happy on that fourth day. He had planned a fourteen-day trip and provisioned the boat accordingly.

No one in the crew ate much during the rough weather, and now with the boat on a fast reach, Larry begin cooking gourmet meals—at least Larry thought his ham and onion quiche was gourmet. He thought of himself as sophisticated and cultured and tried to make the social occasions—lunch, happy hour, and dinner—a time for stimulating conversation, well-prepared food, and good manners. This attitude also brought out his elitist tendencies. David was part of the club because he had graduated from an Ivy League school. Jason, on the other hand, was looked upon like hired help—more like an indentured servant—and as such was tolerated but not completely accepted. And Jason hadn’t been doing a very good job at keeping the weather favorable.

Five days later and eight hundred miles south of the Big Island, Mata‘i was drifting, becalmed in the Doldrums, that band around the planet where the North East trade winds met the Southern trade winds and created an area of calm. The lack of wind had started a few degrees further north than Larry had expected and a day or so earlier. Larry fantasized that if his crew were diligent and played what little wind there was, they could slip through the calm belt in a few days. He saw no reason to waste fuel to power across the six hundred miles of windless seas and stifling heat to find the southeast trade winds. His calculations put the boat about five degrees north and one hundred forty-five degrees west. So, Jason and David were set to work while Larry puttered, and Byron drank. The boys cleaned the boat, repaired things not yet broken, and got ready for the southeast trades that were predicted to soon arrive.

The sun was hot, and with no wind the boys pulled up everything that was damp from below and laid it out on deck or hung it from the shrouds and lifelines. Mata‘i looked more like a backyard clothesline than a yacht. In the evenings Jason played his ukulele. He entertained the others with “hapa-haole” Hawaiian songs he’d learned when sailing beach catamarans out of Waikiki.

Byron began going around naked. He complained that in the hot sticky doldrums even his shorts chafed. Larry joined him in the nudist thing, but unlike his brother, he looked like a withered string bean. Byron was buff and in good shape, even if he did avoid work by blaming his bad back. Jason wouldn’t go naked, and David, with his fair skin, couldn’t take that much sun and wore long sleeve shirts with his trunks.

Jason spent much of his down time reading. He devoured his Norton Anthology of English Literature. He especially liked Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s description of the Doldrums in his The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.

The hot and copper sky

The blood Sun, at noon,

Right up above the mast did stand,

No bigger than the Moon.

David, on the other hand, spent his time sketching and writing letters. Even Larry laughed at some of the sketches David made of him, but David would not let anyone know to whom he was writing.

As Mata‘i crossed the equator at approximately 21:37 GMT on May 12th, in keeping with the traditions of the sea, Pollywogs, any sailor who had not crossed the line, were initiated in to the Order of Neptune in a trial by ordeal. This tradition was more than 400 years old, and the sailors of the great sailing ships endured a diverse collection of pranks—all in the cause of appeasing King Neptune. If successful they would become Shellbacks.

Larry was the first on deck to begin the Mata‘i tradition. He was dressed as King Neptune, naked, wearing a bed sheet for a cape and carrying a coil of rope and a makeshift trident that looked like an oar with some horns attached to it.

Byron showed up next, wearing nothing but a shell necklace, that he said came from King Neptune. He claimed that he had already crossed the equator, and was a certified Shellback, but no one believed him. He sipped his special rum drink and sat in the shade of the awning that had been put up when the boat entered the doldrums.

The Pollywogs, Jason and David, were ordered on deck to begin their initiation. They tried not to laugh at Larry and Byron. Larry order the Pollywogs to strip and asked Byron to tie them up. Byron reluctantly put his drink down and took the rope from Larry. Byron tied the boy’s hands and feet together—lingering a bit too long in front of David’s genitals. Once they were tied up Larry shoved them overboard. Their initiation was to free themselves and swim back to the boat before it drifted away. Neither David nor Jason thought much about being tied up and tossed into the sea. They laughed at the ritual.

Once the boys hit the water, however, it became apparent that they couldn’t float or tread water, and they began to sink. The surface water at the equator was hot; over ninety degrees Fahrenheit, and it grew much cooler a few feet down. As the boys sank into the cold water, they eventually positioned themselves vertically and tried to coordinate their kicking. It didn’t work. As the water grew still colder Jason realized that David was beginning to panic. Jason squeezed his hand and David looked at him. Jason closed his eyes and David knew to try and calm himself. Then Jason lifted his knees and David followed. That allowed them to lift their arms and get a good downward stroke to stop their descent. They found a rhythm—knees up, arms up, and stroke down—that brought them to the surface.

As they broke the surface, they gulped a few deep breaths. The sea was without a ripple—no wind—but even so, Mata‘i had drifted yards away. Larry and Byron were at the rail laughing. Larry saw Jason look his way and waved a cold beer at him. It was surreal. Jason felt so detached from what was happening, like he was in a dream. Then David pulled him close and gasped, “We need to untie our feet.”

Jason nodded.

“Fill your lungs. You hold our feet and I’ll get the knot,” David said.

They took four deep breaths and grabbed each other’s ankles. Like contortionists in a fetal position, David kept their feet together while Jason worked on the knot. They tumbled head over heels and used more air than they’d expected to keep the sea from going up their noses. Their heads were in each other’s crotches, and they were sinking fast, like a ball tumbling downward. David’s dick kept rubbing against Jason’s ear. Jason tuned out everything and concentrated on the knot. Finally, he got it untied and the boys jerked out of their restraints. They straightened up and kicked hard for the surface.

After a few panicked breaths, the boys looked around and saw the boat more than fifty yards away. Byron and Larry were no longer laughing. It looked like they were arguing. After Jason and David got their breath, the buddies looked at each other and burst out laughing.

“You had your dick in my ear,” Jason said.

“I know. It was the worst fuck I ever had.”

“Did nothing for me, either.”

Treading water, facing each other, David’s eyes were dark with fury. “You think Larry knew what he was doing? He could have killed us!”

“Look at us, though; we went along with it.”

“He’s psychotic. Lillian warned us. That man is evil.”

“What are you going to do about it? Swim to Tahiti?”

“Fuck you. Aren’t you pissed?”

The boys struggle to get their hands free.

“When we get back to the boat, I’m going to treat it like a grand joke that we won.” Jason pulled the rope and David’s hand toward him. “I think Byron was really chewing Larry out.”

“Want to bet that he’ll turn the motor on and come and get us?” David pulled the rope back to him.

“Not a chance. That would admit that he made a mistake, and Larry Graff never makes a mistake. The knot is on your side.”

The boys finally broke free, stretched out into a good crawl and swam back toward the boat.

Jason was just as furious as David, but he could see no benefit in telling Larry off. He couldn’t accept that Larry was as malicious as he appeared. Jason knew that Larry was an egotist, but he attributed it to the man’s ignorance.

David kept pace as Jason increased his speed. With every stroke, David wrestled with how to extract justice, or at least an admission of stupidity. Fat chance! He probably should let it go and follow Jason’s lead in maintaining a sense of civility.

It took a good twenty minutes for the initiates to reach the Mata‘i and when they got there, they found the boarding ladder hung over the side. They climbed on board and collapsed on the cockpit lounges. Larry and Byron were no longer on deck. The boys were naked, exhausted, and no one was there to applaud them.

Larry came on deck wearing a large smile. “Congratulations. You two now belong to the Ancient Order of the Deep. Well done!”

Byron followed his brother on deck with an armful of towels. Both were dressed as if they were going to a cocktail party. Byron tossed each boy a towel and studied Jason as he dried himself off.

“I’ll have that beer now,” Jason said to Larry.

“Ice cold beer, coming up.” Larry went aft where two wet socks hung from the mizzen boom. The socks were in the shade and the battery-powered fan from Larry’s cabin was propped up on the dinghy, blowing air on them. Larry took the heavy socks off of the boom and pulled out two bottles of Hinano beer, handing one to each of the boys. “I’ve been saving these for this occasion. Surprised you, didn’t I?”

The beer was cool.

“Evaporation.” Larry proclaimed, smugly.

The boys looked at each other and clinked their bottles.

“Refreshing,” David said.

“What a surprise,” Jason said. “Cold beer at the equator and not an ice cube for a thousand miles.” They saluted Larry with their beers.

“I’m curious, Larry, what was your initiation when you first crossed the equator?” David ventured.

He thought a moment. “I was one of a handful of passengers on a freighter heading from Panama to Sydney. The captain had a ‘Neptune Ball’ and we wore black tie. I drank a lot of champagne.”

David got up and went below, mumbling something about getting dressed.

“Nap time,” Byron said and followed David.

“I guess you have the watch,” Larry said to Jason as he took his fan from the dinghy. “Welcome to the Neptune Club,” he said and disappeared into his cabin.

Jason looked around and saw nothing but a flat, mirror-like sea. It was nearly white in the reflected sunlight, and the surrounding horizon made him feel strangely claustrophobic. He felt there was another world out there, just beyond human perception, and it was so close it made reality seem unreal.

The southeast trade winds arrived on their sixteenth day at sea. Larry had planned to be in Papeete by this time, and Mata‘i was well capable of meeting that schedule. But this is where they were, and Larry set a course of south-by-south-southeast and put up every sail he had. He was happy again and sure that they would make up the time lost in the Doldrums. Everyone checked the knot-meter regularly, especially after gusts of wind, and with the sea still calm, and Mata‘i well-trimmed, she was doing over twelve knots.

As with all ocean crossings, progress was measured in daily nautical miles. The shortest distance they had made in one day was in the doldrums—thirty-eight miles. At six knots the Mata‘i would do one hundred forty-four miles in twenty-four hours. If she had averaged that speed for the entire voyage, it would have taken her just under sixteen days to sail from Honolulu to Papeete. Mata‘i could actually make over fourteen knots with the right sea and wind conditions, and if the current wind held, she could make up some of the lost time and reach Papeete in four days. Larry was hoping to be there in three.

Larry had the guys take a noon sight with their sextants every day. Learning celestial navigation was part of the experience that Larry was providing, and though David had some experience with sextants, chronometers, and nautical almanacs, Jason had not. This was the one time each day when Jason and Larry’s relationship was genuine. Jason wanted to learn, and Larry was a good teacher.

Four nights later, on the twentith day, the wind died. A front had moved up from the south and killed the trade winds. Mata‘i was less than one hundred miles from Papeete and she was becalmed. The morning dawned overcast and still, and it was humid. Larry refused to use the motor to power into Papeete. Byron grew furious as the boat rolled in the swell while the sails slapped back and forth.

“If we turn on the motor now, we’ll be in Papeete tomorrow,” Byron said as the whole crew sat in the cockpit looking at each other.

“There’s a fifty-fifty chance,” Larry said, sitting at the helm controlling the boat.

Hours went by. The crew of the Mata‘i stared at each other, enduring the sickening motion of the boat and the crack of the sails as they popped from one side of the yacht to the other. Larry stubbornly pretended to steer. He couldn’t hold a course and with the heavy overcast hiding the sun they were not going to get a sight that day. Mata‘i had been drifting since four that morning and her last position had put her between Caroline Atoll and Tetiaroa, Marlon Brando’s island.

“We’re a sailboat, and the diesel is an auxiliary to be used to get us out of trouble. It’s not our primary means of power. We leave that to nature and right now nature isn’t cooperating,” Larry said, looking at Jason. “Shouldn’t you be praying or meditating or something?”

“As if that will do any good,” Byron said. “I’ve got a prayer for you: Turn on the god of diesel and let’s move.”

Larry just stared ahead, perched at the helm as if he were truly sailing.

“Oh, for fuck sake!” Byron cried. “I’m out of here when we reach Papeete.” He went below and poured himself a double shot of rum.

The boys went forward and sat on the cabin roof in front of the salon. The last time they were there, Lillian sat between them.

“Are you going to leave, too?” Jason asked David.

“I will if you will.”

“I feel like I’ve made a commitment, and I should see it through.”

“You don’t owe Larry a damn thing. He’s unreasonable and dangerous.”

“I wouldn’t be staying for Larry. I’d do it to find out what kind of spiritual growth this is forcing on me. I’ve been so pissed since we left Honolulu, I’m not sure I can even meditate anymore. I’ve seen people who think they’re so committed to the Spirit when all is going well, run from it when things fall apart. They let their instinct to fight, or get the hell out take over. I’m trying to look beyond those feelings and find another way to deal with the situation.” Jason looked away, trying to get a handle on his emotions. “I don’t know if I’ll be successful. If not, then the spiritual life isn’t for me.”

David put his arm around his friend. “I won’t abandon you to that son of a bitch. I might not have much influence, but I’ll stay for you.”

Larry spent the afternoon looking for Tetiaroa. He thought he knew where it would appear, given Mata‘i’s drift, and where he thought the currents were taking the boat, but he never saw the island. By nightfall he was sure they’d passed it. Still, he wouldn’t fire up the motor even though he believed he could see the glow of light from Papeete. Larry was determined to sail into port the next morning.

After a meager dinner of canned food, and the dinner dishes had been cleaned and put away, the boys went forward to their space on the cabin top. Byron was attempting to hold a course. Larry was cussing at the Aires self-steering gear—he hadn’t completely given up on it. When there were decent winds, the Aires worked well. Why Larry thought he could get it to work when there was no wind was puzzling. Mata‘i had been drifting for almost twenty-four hours and everybody had accepted that Papeete was another day away.

Jason was meditating, which made him extra alert. “Did you hear that?” he said.

David turned his head like a direction finder until he was looking to where Jason thought he’d heard the surf. “Yeah. Over there.”

The boys went to the rail and looked out into the darkness. The cloud cover was thick and the night dark. Then Jason saw a pale line of white off the port bow and pointed it out to David. “Surf!”

“Larry! Byron! Surf off our port bow!” Jason yelled.

Both men looked to where Jason was pointing.

“Impossible.” Larry said, walking to the port shrouds. “We passed Tetiaroa late this afternoon.”

A slight breeze drifted over the boat, coming from the direction of the surf, and it smelled like land. The mainsail jibed at the same time that a larger than normal swell rolled under Mata‘i.

“That’s a wave and it’s going to break,” David said.

“Smell that!” said Byron. He slid off the helmsman’s seat and stood at the wheel for better control.

Suddenly it became clear that the boat was about sixty yards off a reef and drifting into the impact zone of the waves.

“Larry, turn on the fuckin’ engine before you lose your boat!” Byron yelled.

Larry just stood there, staring at the now apparent surf, and not moving. The boys ran back to the cockpit and David started the vent motor that cleared the bilge of fumes. “Release the shaft brake, J.J.”

“I’m starting the goddamn engine now,” Byron said shoving David aside. “If we blow up, we blow up.”

Jason had the seat hatch raised and was turning the extension into the brake clamp when another swell rolled under the boat and knocked him off-balance. Byron hung onto the helm and pressed the starter button. He shifted the motor in gear and gave it some throttle.

“Wait!” Jason said. “The brake’s not off!”

Byron throttled back but the brief turning of the shaft had locked it to where Jason didn’t have the purchase to release it.

“Dave, get the brake from below,” Larry finally joined the effort to get the boat moving. He took over the helm from Byron.

David ran below, and with Jason working from topside, they were able to release the brake clamp. “We’re free!” Jason hollered.

Larry put the boat in gear and gave her some power. The reef was clearly visible, and the boat was still in the crash zone of the surf. Larry was not acting quickly enough. Byron shoved the throttle to max, pushed Larry aside, and then turned the boat ninety degrees to plow through a couple of large swells that were already breaking. Everybody held their breath, hoping that Mata‘i had enough power to get through the waves before they drove her onto the reef. She did have the power, and the Mata‘i cleared the impact zone. They were safe, and the crew relaxed.

Byron then declared that they would be motoring to Papeete and demanded a course. Larry brought up his radio direction finder and found two beacons that he triangulated to get them to Papeete. No one said anything about Byron taking over in the emergency.

Mata‘i approached the pass through the reef into Papeete harbor at first light the following day. The swell had increased. There was no wind, and large drops of rain randomly fell from the sky. Byron motored the Mata‘i into the harbor while Larry called customs. At the same time, a fifty-foot sloop backed into the last slot left along Boulevard Pomare. “That’s not looking good,” Byron said.

The boys were standing on the stern, ready with the mooring lines. “What’s wrong?” Jason said.

David saw the situation. “That sloop took our berth. They moor here like the Caribbean, stern to. You just put a gangway off the stern and you’re ashore.”

Larry came back on deck livid. “That was the last place along the quay. Another boat from Honolulu.” Larry shoved Byron out of the way and took over. He turned his boat a hundred and eighty degrees and powered down to where the street turned inland, and the quay stopped. Beyond that was a rock revetment and a bank of grass that made a waterfront park for a few hundred yards until the shore turned into mangrove and mud flats.

“We’ll have to anchor off the park,” Larry said, maneuvering Mata‘i to a spot ten yards from the shore.

After the bow anchor was set, the boys lowered the dinghy into the water and rowed ashore, taking a stern line with them. They took the line up the grass and tied it to a nearby coconut tree. Using the tree as a makeshift winch, they pulled the stern of Mata‘i as close to the shore as was safe and tied her off. Mata‘i had finally arrived, after twenty-two days at sea.