Chapter 23

The South Pacific

Monday May 29, 1989

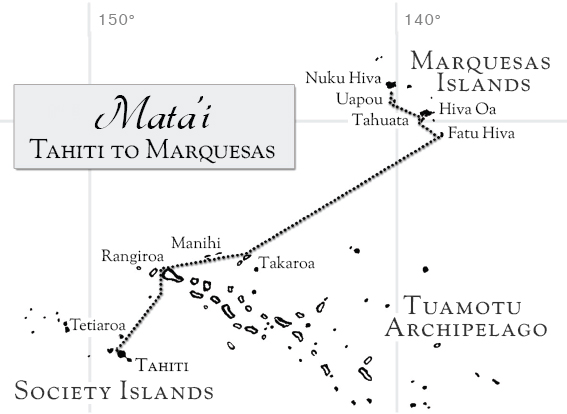

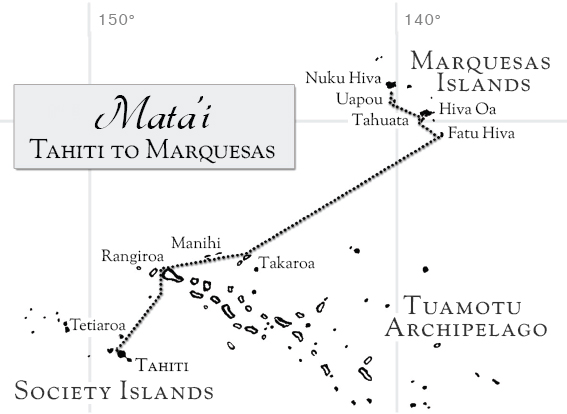

The Mata‘i left Papeete early in the morning—a week after arriving and two days after Melanie had moved aboard the boat. They took on water and fuel at the commercial pier. The boys hoisted the sails outside the reef and Larry set a course around the north shore of Tahiti, past Point Venus and into the South Pacific. Larry planned to island hop through the flat Tuamotu Archipelago, which meant “the distant islands.” But sailors called them the “dangerous islands.” Culturally the people there were the same as the people in the Society Islands—Tahiti, Moorea, Bora Bora. They spoke Tahitian, danced the ‘upa‘upa dances of Tahiti, and in ancient times, followed the same gods. But they were outliers, far away from the social core of Tahiti, struggling to survive on an archipelago made up of atolls and reefs. The land barely reached six feet above sea level. The trade winds blew over the hardscrabble earth without resistance, and the currents were unpredictable and treacherous. Larry was not going to sail through these islands at night.

With Mata‘i on a broad reach, Larry estimated a day-and-a-half at sea before reaching the first island, Rangiroa. Jason and David settled into their at-sea routine, which meant trimming the sails and maintaining their course. Larry was mostly tinkering and only joined the boys during social hours. Melanie enjoyed the sail.

Larry always cooked the main meals. There was a table in the cockpit, and when the weather cooperated, everyone would take their meals there. But that didn’t mean the crew would be eating holding paper plates in their laps. No, the table always had a cloth on it, and some sort of centerpiece. Ashore, Larry made the centerpiece out of flowers. At sea, he’d pull together a centerpiece using shells and glass balls arranged in a wooden bowl. Dinners always started with cocktails, and Larry served only French wine with the food.

Melanie enjoyed steering the boat. While Larry was below cooking, Melanie was at the helm, and the boys bombarded her with questions.

“Did you meet any of your half-brothers or sisters in Tahiti?” David and Jason burned with curiosity about Larry and his family. Melanie just smiled.

“I didn’t,” she said. “I did meet three of Dad’s five wives. One was younger than me.”

“Everybody in Honolulu speculates about his years in Tahiti. I’m sure the stories are exaggerated, but there are people at the Hawaii Yacht Club convinced that Larry’s offspring are Tahitian royalty now ruling Tahiti.”

“Wouldn’t that be nice?”

“What did your dad do there?”

“I thought you both knew that story.”

“Only the rumors,” Jason replied.

“Dad’s family was wealthy, from Bryn Mawr on the old Main Line of Philadelphia. My grandmother was a Flagler. His upbringing was boarding schools and Palm Beach vacations in the winter and summers in North Haven, Maine. That’s where he fell in love with sailing. He graduated from Dartmouth rather young, at twenty, and left to see the world on a steamer sailing from New York to Sydney through the Panama Canal with stops in Havana and Papeete. He didn’t like Havana but got off the steamer in Papeete, where he stayed until World War Two.”

“Then he saw the unspoiled Tahiti,” Jason said.

“Not really. Fletcher Christian saw the unspoiled Tahiti. From then on it was downhill. At least that’s my opinion.”

“He must have had a few girlfriends?”

Melanie laughed. “Well, my dad’s always been curious, except about what I was doing. But he needed to know everything about everything else. So, he learned all there was to know about Tahiti, including the language. He already knew French. Of course, he loved many women. He got married to a princess from one of the chiefly families. I’m sure he never told my grandparents.”

Melanie looked at Jason and David like the reporter she hoped to be. “If this is boring, stop me. I only heard this story last week. My mother won’t talk about him. Frankly, I have a hard time relating to him.”

“Didn’t you see him growing up?” Jason said.

“Not much. He got into all that Dr. Green crap and mom couldn’t stand those people.”

The boys looked at each other and started to laugh.

“I’m sorry.” She realized that perhaps she had hit a nerve.

“No, it’s so honest. It’s wonderful,” Jason said. “Go on.”

“I didn’t know Dad had so many friends in Tahiti. He and I visited James Norman Hall’s widow a few days ago and saw where the Bounty Trilogy was written. Mrs. Hall treated him like a son. Did Dad make you read the Bounty Trilogy?”

“I’m on the last book,” David said.

“I guess he found his paradise,” Melanie continued. “He had a son. He said he tried to work with the territorial president to create some kind of economy for the islanders—his major at Dartmouth was economics—but the war came along, and he returned to the states.”

“I never knew any of this,” Jason said. “He doesn’t like to talk about himself.”

“You’ve got that right,” Melanie said. “He never said boo to me until I got here and all of sudden, he never shut up.”

“And then what happened,” David said.

“He received a commission in the Navy and after a couple of years in San Diego he was sent back here. He was second in command at the big allied supply base on Bora Bora. He gave me a whole history of World War Two as well. Want to hear that too?”

“I’ve nowhere to go,” Jason said.

“Bora Bora was beyond the reach of the Japanese. War matériel from San Diego to Hawaii to here, and from the East Coast through the Panama Canal could move without danger from Japanese planes and submarines. The base supported the campaigns to take back New Caledonia and the New Hebrides. It had seaplane runways, fuel—seven thousand men—so I guess it was a big responsibility.”

“I bet his family was happy to see him back.”

“No. His wife and child had drowned in a boating accident. Their boat sank in a storm while sailing from Moorea to Papeete. Nobody knew how to reach Dad, so he didn’t find out until he got back.”

“That’s horrible,” David said. Jason could see that David was readjusting his opinion of Larry and what he had suffered.

“Well, he became one of those rogue South Pacific officers Michener wrote about in Tales of the South Pacific. He drank way too much. He started a black market in war surplus and had a fleet of schooners sailing the islands. He probably ran a few spies too! When the war ended, he had a legitimate trading company that supplied islands from Rarotonga to Samoa and throughout French Polynesia. But he said he was miserable. All he could think about was his lost family.”

“What about the Navy? They couldn’t have liked what he was doing,” David said.

“I don’t know. He never mentioned any problem with the Navy. He was honorably discharged in 1946, when they closed the base in Bora Bora. Two years later he sold his business to his Tahitian partner. I don’t think he ever wanted to come back. He went to New York and became an investment banker.”

Larry came on deck with a tray of hors d’oeuvres. “Are you giving away all my secrets?”

“Dad, you never told these guys your history. How come you never told me until last week at the hotel?”

“It doesn’t mean anything. What’s human history worth, anyway? I’m not that person. Haven’t been for decades. You’ve only known me since I met Dr. Green. His teaching changed my life. I admit I can’t always live up to the ideal, but I’m trying to live up to that now.”

“But your story is a great adventure. You should tell it,” Melanie said.

“Bollocks on that. The greatest adventure is discovering your spiritual nature. You should ask Jason about that.”

“Is there something going on here that I need to know?” Melanie asked.

“We’re out to discover ourselves,” David said. “You know, face adversity to discover the depth of our character.”

Melanie didn’t like being excluded. “What’s my role in your little drama?”

“That’s still to be determined” Jason said. “Perhaps you’re the witness.”

“I hope this isn’t a Greek tragedy,” she replied.

Larry’s hors d’oeuvres were excellent: a poisson cru on slices of baguette. He baked a Tahitian snapper in coconut milk and served it with island sweet potatoes and a leafy vegetable similar to spinach. Comparing this with the first night out of Honolulu was impossible. The angle of sail was smooth broad reach with a gentle quartering sea—it was like being on a cruise ship. The al fresco dinner in the cockpit, with a warm fair wind was the kind of experience everyone wanted to remember. The setting sun over the transom turned the ocean into a golden highway, one without markers, seemingly infinite in its reach. The waxing moon was three-quarters full and already a few degrees above the eastern horizon.

Maybe Melanie was the civilizing quotient Larry needed. Maybe now this was going to be the voyage that Jason had sold to David in Europe? David liked this Larry. And he liked Melanie, too.