ON 1 SEPTEMBER 1941, THREE DAYS after our initiation raid on Le Havre, we were called to an early afternoon briefing. The Tannoy shouted out, “Ops are on for tonight.”

The wing commander faced the assembled crews in the theatre and announced, “Well, chaps, it’s quite a big effort tonight. Our target is Cologne, and we want to give the marshalling yards and factories there a good smashing.”

The red tapes on the map of Germany showed our route into the Ruhr valley, called “Happy Valley” by the aircrews because of the casualties already suffered from raids on this heavily defended area. Cities in the Ruhr harboured the highest percentage of coal-, steel-, and chemical-producing factories in Germany, so it was defended with the heaviest concentrations of flak and night fighters in Europe. Announcements of targets in that area were usually greeted with grimaces and a few audible groans from assembled crews.

The now-familiar briefing on bomb loads, target pin points, codes, expected flak and fighter activity, and the all-important weather followed. Then off we went for rest, early dinner, and our plotting preparations.

We had a surprise waiting for us when we reached the plotting room. We were introduced to our new front gunner. I knew Wilson Poirier right away. We had trained together at OTU and I had been talking to him in the briefing theatre when neither of us knew that he would be joining our crew. Munroe was not about, and I cannot remember seeing him again. We were never given any explanation for the crew change.

Willy and I were to become good friends and frequent companions on our sorties into London on leave. He was a French Canadian from New Carlisle, Quebec, but I cannot remember him speaking anything but fluent English. Perhaps he would have spoken French if I had been able to speak it as well. I wasn’t to learn until much later that, like Len, he was a “star-crossed” member of that first crew I belonged to.

Our crew plotting and preparation completed, we dressed, loaded ourselves up with all our paraphernalia, and took off in the crew lorry for dispersal.

The dispersal area where our Wimpy was parked was a beehive of activity. As with the other Wimpys nearby, the ground crew of fitters, engine and airframe mechanics, armourers, petrol bowser drivers, and other odd erks were swarming all over and around our aircraft.

The flight sergeant in charge of this particular ground crew rode about on the ubiquitous issue station bicycle, barking out orders or reproofs as he thought the occasion or the culprit demanded. Ground crew flight sergeants were called, among others things, “the Chiefie.” The sergeant spent some of his time chasing erks away from their “chai and wads”* dispensed by the ever-present NAAFI wagon (the Navy, Army, and Air Force Institute snack service staffed by volunteers).

The NAAFI service was a great comfort and morale booster to the indispensable ground crews, toiling in wet, cold conditions often so miserable that we marvelled at their ability to get our aircraft repaired, tested, bombed up, and serviced in time for operations.

Sheltering under the wing of our Wimpy one wet night, I was startled by the sight of two young women of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) pulling a 250-pound bomb on a dolly up to the belly of our aircraft. Soaked to the skin, one WAAF cranked the winch to hoist the bomb up into the bomb bay, while the other WAAF steadied the bomb with her back! These young WAAFs had joined their male comrades in most of the ground crew trades. Although it was probably of concern to wives and sweethearts, the companionship the WAAFs provided gave us a much-needed emotional lifeline.

I have always believed that the contributions the ground crews made to the war effort have never been adequately recognized. While they did not face the dangers the aircrew confronted, they suffered a share of casualties from the frequent bombings and strafing of the airfields. They also suffered from the considerable stress of handing over the aircraft they had laboured to prepare for the night’s operation to a crew they too often never saw again.

With a thumbs up from the Chiefie, and the servicing log signed and accepted by the captain, our Wimpy lumbered out to the live runway. Cleared for take-off by the control tower, at precisely 2000 hours we roared down most of the grass runway’s length and lifted off into a clear, darkening night on the second “op” of our operational tour. We learned later that we were in the company of thirty-four other Wimpys and twenty Hampdens from various squadrons in Bomber Command.

As I sat in the dim light of my small desk in front of the myriad dials and knobs of my transmitter and receiver checking frequencies and getting attuned to the steady throb of the Bristol Pegasus engines, I thought of the job Len had in front of him. He knew that on this trip I would not be able to get bearings for him on our outward legs as I had been authorized to do on our first op. At this stage our Wimpy had not been fitted with “GEE,”* but it was a clear night so far, so he should have been able to get himself some star fixes from his bubble sextant.**

Our given route to the target of Cologne was to take us over Holland, south on a diversion to the small French town of Givet, just over the border of Belgium below Dinant, then on a heading of 045° to the target. Len had gone forward to the bomb aimer’s position where he could get a clear view of the ground. Suddenly he announced to Sgt B, “The Zuider Zee is right below us. It gives us a fair pinpoint!” I left the frequencies I had been monitoring in case of a recall or other orders and clambered back to the astro dome to see the famous inland sea.

Soon we saw a “V” made up of lights pointing towards our turning point of Givet. These were goose-neck flares laid out on the ground by the Dutch resistance, at great risk, to help RAF bombers reach their targets. We wondered if they could know what our target was, or if they just knew the general direction.

Soon we were over Givet and making our turn onto course for the target. We had been told to keep our eyes peeled for night fighters, and as we neared the target I went to the astro dome. Ted Crosswell, standing beside Sgt B, cried out, “There are the fires straight ahead. Must be Cologne! There’s a lot of flak bursting over the city.” We could all see it, and we also saw the white searchlight beams probing the sky.

Our captain then announced, “I’m going to stooge around a bit on the outskirts just to see what’s happening before we go in. Navigator, you’d better come forward now and get ready for the bomb run.”

Orange mushrooms with dirty brown rings expanding rapidly from their centres began to sprout around us, and the whump of the exploding flak shells could be heard above the roar of the engines. It was accompanied by the sweet, sickly smell of cordite. Outskirts of the city or not, we were beginning to run into a great deal of heavy flak.

At 8,000 feet we began to attract the attention of the medium flak gunners. I watched with a nervous fascination as the streams of mixed yellow, green, and some red shells snaked up towards our Wimpy in an “S” curve. They appeared to leave the ground in a lazy, slow motion but accelerated rapidly as they reached our level and went past our wings at incredible speed. Most of them seemed to me to be aimed precisely at the end of my nose.

Sgt B began to jink the aircraft to avoid the increasing flak, and called to Len on the intercom that he would be making our bomb run now. Immediately, we all heard Ted’s protest: “What do you mean we’ll start our bomb run? We’re nowhere near the railway yards, and I didn’t bloody well come here to bomb bloody German cow pastures! We’ve got to get right into the city to get to our target, which is over there to port, about ten degrees.”

This outburst must have struck a nerve with our captain, who obviously had the “wind up” (as we used to say of those whose fear or panic had taken over) and was perhaps loath to go in to the target over the fierce firestorm already consuming parts of the town centre. He told Len to stand by, and altered course as Ted had demanded.

By now the flak had intensified. We were surrounded by exploding shells whose blasts were thumping under our feet as the whole airframe shuddered. The sky was no longer clear but covered in the brown fog of the deadly fireworks display ahead.

I saw two other Wimpys over the target area. One of them was caught in a cone of three searchlights. Suddenly he exploded, and became a monstrous red and brown expanding ball. Pieces of the aircraft fell through the searchlight beams, sparkling in the white light. Later that night, that Wimpy would be marked FTR (Failed to return) on the board in the ops room for that Wimpy.

Len’s voice came over the intercom with a heading of 350 to the target. “We can start our run-up now.” Sgt B straightened out for the approach, and Len started his corrections with “left, left, steady … r-i-g-h-t, steady … bombs gone!”

“Let’s get out of here!” cried our captain as he threw the Wimpy into violent corkscrew turns to avoid the flak that appeared as an almost impenetrable curtain of exploding shells.

I had to get back to my seat to send the “bombed primary target” coded message to Bomber Command Headquarters. With the captain’s okay I immediately set up my transmitter on the designated frequency and, waiting my turn on the busy wavelength, got the message out and got the “R-Ack-R” receipt. Len than gave the captain a tentative heading for home, and we started chatting about where our bombs had hit. Ted was sure we had come very close to our target, and Len agreed.

Having gotten my important message away, I leaned out into the passageway to tell Len that I would get him some bearings as soon as we had reached the Channel. I glanced back down the fuselage at the precise moment a shell exploded halfway down to the rear turret with a sharp crack and a brilliant flash of light. The blast hit me full in the face. My eyelids closed tight, and my eyes felt as if they had been sand-blasted shut. I was blind! I felt panic rising through my body. Of all the things I had imagined might happen to me, being blinded wasn’t one of them.

Len grabbed my shoulders, and I shouted that I couldn’t see. Just then we were rocked again by shrapnel hitting the aircraft. Len picked up the microphone that I had dropped and called the captain to say that smoke was coming out of my wireless set.

Ted clambered back quickly to look at the equipment with Len. It had been hit by pieces of the shrapnel, but Ted announced that the smoke had cleared and there seemed to be no risk of fire. He then hurried back to the rear to check on damage from the exploding shell. He reported a few stringers and some fabric missing but no serious structural damage. George also reported that he was all right, and added a few cockney comments on the rude reception we had been given.

Len set about trying to do something about my eyes, and managed to get some water into them. This helped to relieve some of the painful burning, and I was extremely relieved that I could see something again, even if through a smoky haze.

I had trouble focusing on my dials and meters, but at least I could make them out if I really strained and concentrated. I was dismayed on a quick test of the transmitter when I got no reading on the antenna output meter — it wasn’t working. At least I had gotten the bomb message away. But now I began to worry about getting bearings for Len as we left the target area. Wind up or not, our captain’s experience had pulled us through it.

I concentrated now on trying to get my transmitter to work. I managed to get my hand around to the back of the set, and found some dangling wires that obviously had been broken loose. I had no idea where they had come from, but I found what felt to be connection points and twisted the loose ends into those fittings. I also found some loose plates that fixed back in positions that seemed to fit.

I had been working longer than I thought because Len was telling the captain that he believed we were nearing the Channel coast. He didn’t sound very sure of himself. The clear skies that had made us better targets for flak or night fighters, but had also given Len stars for position lines, had clouded over. He was forced into straight DR, or “dead reckoning” navigation, and was having trouble finding his winds.

The captain was not pleased, and the whole crew seemed to be getting edgy, largely, no doubt, the after-effect of our rough time over the target area. Len leaned over to pull my sleeve. Rather than speak over the intercom so all would hear, he pulled my earphone aside and asked if I could get something out of my set for him. I got the distinct feeling that we were lost.

I turned all my attention to the transmitter and tried several frequencies to no avail. At least the receiver seemed to be operating. The captain kept asking Len for a new heading, sounding more and more frustrated and worried.

I worked at the transmitter for a long time. In frustration I tuned into a station at Hull, knowing it was a powerful station but that it might be too far north to hear me. On the third try I got a faint response, so I quickly sent back the code request for a fix, and held down my Morse key for a long dash. Back came the weak, barely audible code for the first four of the eight coordinates I needed, and then the signal faded out. I tried again and got up to six of the figures I needed before the signal faded again.

With Len leaning over me now, I waited a few minutes, and had a sudden brainwave. I reeled out the trailing antenna, and used the transmitter output meter to judge when I had the optimum length for the Hull frequency I was on. Then I tried again. Eureka! This time I got all the coordinates we needed for a good fix of our position. Like a man grasping at straws, Len snatched the slip of paper on which I had hurriedly written the coordinates, and soon called out a course for home base.

The captain handed over the controls to Ted and came back to look at Len’s map. He was as startled as Len and I had been to find that we were over water, north of Holland, headed for the North Sea. By this time our fuel was getting dangerously low; if we had kept on our previous heading we would have had to ditch when we ran out of fuel.

We were lucky. From then on I could get nothing out of my equipment.

Our captain warned us that we weren’t out of hot water yet. Our fuel was low, as he and Len had figured out, and we had to make for the nearest airfield as soon as possible. Our new course put us on track to southeast England, and as we approached land Sgt B called out that we would have to use the Darkie procedure to try to get in somewhere quickly. I had already switched on the TR9F set under my seat so we might get the “squeaker” warning of too-close barrage balloons, so I readied it to contact Darkie stations by voice.

Ted called “Darkie, Darkie, this is N Nan, do you read?” I had the IFF switched on by this time, so we were identified as friendly and back came the sweet voice of the WAAF ground operator.

“N Nan, this is Darkie. We have you all right. Follow the lights.”

I hurried forward to peer over Ted’s shoulder in time to see two searchlight beams switch on to project vertical shafts of light ahead of us. I could make them out through my still-hazy eyes, which burned and felt as if they were full of grit. The beams then went horizontal, pointing slightly to the northwest, and Sgt B swung us over to follow them.

Before we made our next turn, an unmistakable Aussie voice came over the radio throughout our intercom. “Darkie, Darkie, this is P Peter, do you read?” No reply. After several tries, the Aussie got frustrated and called, “Darkie, you little bastard, where are you?” This time, the sweet WAAF voice came back, but only after blowing in her microphone several times to test it, an annoying habit of some operators.

A cool Aussie shot back with, “You’ve blown in my ear three times, Sheila, now kiss me!” A brief pause ensued before the Aussie got his direction. This little exchange gave all of us a lift just when we needed it.

By now we had followed our last searchlight beams and were on the approach to an airfield that turned out to be West Malling, in Kent. This was primarily a night fighter station. It was some distance from our home base of Marham, but was very welcome nonetheless.

After a cursory debriefing by a grouchy intelligence officer rudely torn from his bed, we were taken to the sergeants’ mess and told that we would have to make ourselves comfortable on the sofas and chairs for what remained of the night, or rather morning. We had been in the air over six hours, and it was now past 0300 hours.

Still in our flying clothes, we stretched out on sofas or the floor rug. It was hard to calm ourselves down enough to actually get to sleep, although Ted managed to doze off. Willy Poirier looked pale and strung out. He had had the front row seat overlooking all the action, of course, and it had an effect on him. I sat with him and chatted for a while until he seemed to feel a little better. I suspected that he had been airsick during our flight.

Len urged me to go to the station hospital to have my eyes treated, but I insisted that I would wait until we got back to Marham. This wasn’t bravado on my part. I was afraid that if the medics got hold of me I wouldn’t get back to our home base to rejoin my crew for goodness knows how long.

I turned to my logbook, in which I had neglected to make entries during all the stress of trying to get the wireless set working after we left the target. My eyes were still burning, but I could just make out the logbook pages enough to write in times of transmissions and message content. I had to rely on memory, and I hoped the debriefers wouldn’t check my times too closely. Only when I finished this could I rest my back against a chair to try to get some sleep. I found it hopeless; I could not get the sight of that exploding bomber out of my mind.

In the memory of every Bomber Command survivor is the sight of other bombers exploding, and the knowledge that later the same night FTR would be entered on the ops boards at the crews’ home bases. In his book The Right of the Line, John Terraine quotes John Pudney’s poem “Security.” It’s about pre-take-off precautions, and for me it expresses the individual tragedies in all the losses:

Empty your pockets, Tom, Dick and Harry

Strip your identity; leave it behind.

Lawyer, garage hand, grocer, don’t tarry

With your own country, your own kind.

Leave all your letters. Suburb and township,

Green fen and grocery, slip-way and bay,

Hot-spring and prairie, smoke stack and coal tip,

Leave in our keeping while you’re away.

Tom, Dick and Harry, plain names and numbers,

Pilot, observer, and gunner depart,

Their personal litter only encumbers

Somebody’s head, somebody’s heart.

At daylight we roused ourselves and walked stiffly into the adjoining mess hall for an early breakfast. Even the simulated eggs and the cold English toast tasted good. We were dehydrated and hungry.

Our Wimpy had been inspected, refuelled, and declared fit for flying. There were numerous holes in the wings and fuselage, and several square feet of fabric and stringers were missing, but this never seemed to upset the old Wimpy unduly. With its geodetic structure the airframe could take an enormous amount of damage before the flying stability of the aircraft was seriously impaired. We clambered aboard, and were soon on our way to Marham.

Marham operations knew all about our misadventures, and we had to undergo a long, critical debriefing. I handed in my logs to the duty wireless operator, and was told to report for a radio debriefing later in the day. I was then sent off to the duty medical officer to have my eyes examined.

The medical officer washed my eyes out with some kind of soothing potion that relieved the burning greatly; he pronounced them okay. Apparently my eyes had been filled with dirt and grit that blew off the floor of the aircraft when the shell exploded. Later I found I had a permanent tiny black spot in one eye that was annoying only when I looked into a clear sky; sometimes it made me think twice about whether it was the spot or an enemy aircraft in the distance. The medical officer ordered me to spend the rest of the day in the sick bay, and I fell gratefully into the cool white sheets of the hospital bed, by now thoroughly exhausted and emotionally spent.

When I did finally get my radio debriefing, I was told there was no possible way that my transmitter would have worked the way I had blindly wired it back together. All I could say to them, as the flight sergeants shook their heads, was that they could ask our navigator, because if I hadn’t received that fix from Hull, we would be at the bottom of the North Sea.

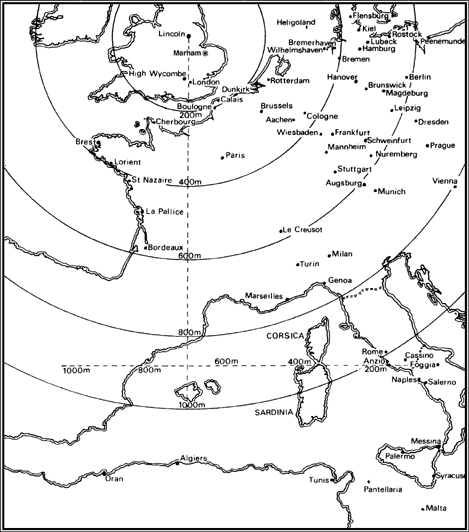

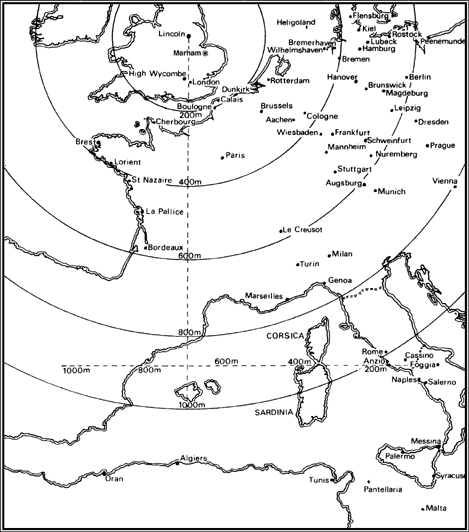

THE EUROPEAN THEATRE OF AIR OPERATIONS

* “Chai,” (pronounced shy), Arabic for tea, was transported back to Britain by servicemen returning from the Middle East. “Wads” was simply British vernacular for buns.

* “GEE” was a codename for a radio-pulse system by which the navigator could fix his position by reference to three transmitting stations in England. A more accurate radar-pulse system, codenamed “OBOE,” was introduced later.

** To the layman, navigation might seem to be a fairly simple exercise. The pilot draws a line on his map from departure point A to destination point B and notes the direction in degrees. Then he flies on that heading for the time taken to cover the distance at his air speed, and voilà, he arrives at his destination. As rear gunner George would say, “Not bleeding likely.” For that pure theoretical flight the conditions would have to include completely still air, a constant temperature, a totally stable aircraft, and a pilot who could keep the aircraft perfectly on the heading he had been given. I doubt that all of these conditions have ever been experienced together in the history of flight. The wind, which can vary wildly in direction and strength between a few thousand feet in altitude, is the main culprit. The winds also change constantly en route, even at the same altitude. The navigator must work constantly to compute the wind and give offsetting or compensating course headings to the pilot.