MY RETURN TO THE TRANSPORT section stirred little interest or curiosity. The staff were more concerned with the sad condition of the truck. I told the Australian CO that a posting was coming up, and it was unlikely that I would be returning to the section. He thanked me for helping them out, wished me the best of luck, and shook my hand. Then, with sudden concern, he exclaimed, “What have you done to your head?” I was a sorry sight. The blood had seeped through the old bandage. I told him, very briefly, what had happened, and he hustled me quickly to the section first-aid clinic. The medical assistant on staff took a look at the wound on my head. He didn’t think it needed any stitches, but he cleaned it up and put a fresh dressing on it to guard against infection.

Since I hadn’t been taken on strength officially, there was no paper work of any kind involved in my departure.

I walked wearily the few blocks to Hurricane House. The flight sergeant greeted me warmly, but asked no questions. Mahmoud was beaming with relief and delight, and proudly produced the money he had been keeping for me. Not a piastre was missing. When I pressed a few pounds into his hand he recoiled. “La, la,” he cried, “That is far too much for such a lowly person as me!” I told him he was not a lowly person, and that I would be unhappy if he didn’t take the money, which he had truly earned. At this, he gave in and accepted his reward.

Mahmoud had kept my room undisturbed for me. In my exhausted state, I just wanted to fall into bed, but I was too dirty. I climbed gratefully into the warm bath my faithful servant quickly prepared for me, and lay soaking up to my neck in blissful relief. The cool sheets of my bed were sheer luxury after my desert pallet. Although it was before dinner time, I did not open my eyes until 0700 hours the next morning, feeling blessedly rested and restored.

After I had devoured a large breakfast, the flight sergeant informed me that he had instructions from Air Force Headquarters that I was to report that day to the personnel officer.

At 0900 hours, I reported to a flight lieutenant at AHQ who informed me that I was posted to No. 5 ADU, the Aircraft Delivery Unit, headquartered at Abu Sueir, and that I was to report back in two days for a date of transfer.

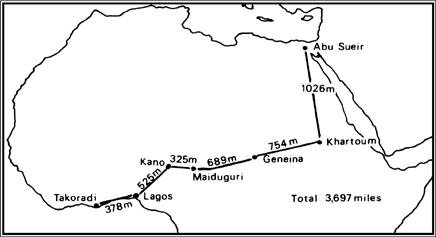

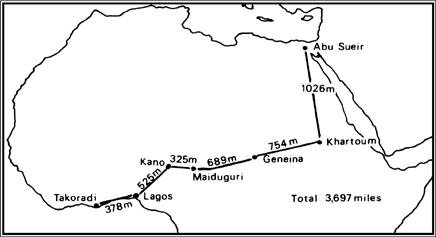

I had been told quite a bit about this unit by my convalescing companions at Hurricane House. I wanted no part of it. It was a ferry operation, delivering aircraft and supplies on a route from Takoradi on the western gold coast of Africa, across the continent to Khartoum in the Sudan, and then northward to Abu Sueir. Once on that unit, I could be buried in Africa for years.*

Somehow, I had to get out of this posting, and find a way to get back to England. I struggled for a solution for hours before it came to me. I remembered that the flight lieutenant who had curtly informed me of the 5 ADU sentence was the type who prided himself on perfection. I devised a plan, and decided to give it a try.

Reporting as instructed, I saluted the personnel officer smartly and stood at attention in front of his desk. As soon as he mentioned a date for reporting to 5 ADU I feigned great surprise and fibbed shamelessly, “But you must have made some mistake, sir. You told me on Thursday that I was posted to the United Kingdom!”

THETAKORADI ROUTE

At this, the flight lieutenant’s face turned red, and he bristled, “What do you mean, I made a mistake? I’ll have none of your impertinence! We do not make mistakes in this department. If I said you’re going to the U.K., then that’s precisely where you are going.”

“Yes, sir. Sorry, sir,” I said with a suitably chastised look on my face.

He shuffled some files on his desk, opened one, and looked up at me in some little triumph. “You are to report to No. 23 Personnel Transit Centre at Helwan in one week’s time to await embarkation to return to the U.K. by ship for further disposition. Make sure you are on time. That’s all!”

I couldn’t wait to escape the office. I could hardly believe my ruse had worked, and I congratulated myself on my thespian skills and amateur psychology.

I said goodbye to my friends at Hurricane House, and to my faithful Mahmoud, who was again in tears, and reported to the transit camp at Helwan, which was a short electric train ride to the city’s far outskirts. What I found was a far cry from my luxury room at the convalescent hotel. I was shown to a tent that had no extra cover to help as a heat shield. A thin, straw mattress pallet lay on the sand floor. There were no other furnishings! This was even more Spartan than my quarters on the squadron at Kabrit. A wooden building housed the sergeants’ mess.

A few days after my arrival at Helwan, I was walking towards the sergeants’ mess when I saw a tall, familiar-looking airman approaching me. As he came closer, I saw that he was a flight sergeant pilot, and then exclaimed out loud, “My God, it’s Jack Kelly!”

Jack was a high school friend from Toronto. I had not even known that he was in the air force. Jack’s eyes widened as he recognized me, and echoed my surprise. “It can’t be Howard Hewer! What in hell are you doing out here?” A good question for both of us, I guess, but it was a remarkable coincidence that we should meet in this remote area of the world.

We shook hands warmly, and sat down in the mess to tell each other our stories. Jack had been flying Hurricane fighter-bombers on No. 33 RAF Sqn in the Libyan desert until they had to make a hurried escape from Rommel’s tanks as they swept eastwards towards Alamein. He also was now posted back to the U.K. for reallocation. This was a happy reunion. We celebrated with many trips into Cairo on the electric railway, sometimes returning from Groppi’s cabaret a little the worse for wear.

Our remarkable meeting followed another that was even more unlikely. Earlier in the year, on visits to Cairo, Jack and I had separately met another high school friend, Bill Galer, on one of the main Cairo avenues. At Parkdale Collegiate, Bill had been a sports star, winning honours on the gymnastic team. Now he was an RCAF observer, and had flown with 9 Sqn RAF in England. He was passing through Cairo to India, where he flew on Wellingtons of 215 Sqn bombing the Japanese in Burma. It did indeed seem a small world.

On 5 November, everyone was celebrating the news of General Montgomery’s great victory at El Alamein. Rommel’s Afrika Korps was in a headlong retreat that would end with final defeat in Tunisia in 1943.

On 17 November, our group of about eighty aircrew was instructed to report to the supply section to be kitted out for the return to the U.K. We were to leave that week, and it was a poorly kept secret that our destination was the port of Suez, for embarkation.

At the supply section, we were completely dumbfounded by the items we were given. The kit included desert water bottles, khaki shorts and shirt, straw topi (we already had one), cartridge bandoliers, and canvas pack-sacks. We protested that this was all desert equipment, and we weren’t going to the desert — we had just come from there! Most of the equipment we had never been issued when in the desert, and we certainly had no use for it now. We protested in vain, and were ordered to board buses with all this gear. Someone was slavishly following standard orders for desert kit.

We arrived at Suez and immediately boarded a magnificent liner, Holland-America Lines’ Nieuw Amsterdam, which had been completed just prior to the outbreak of war and converted immediately to trooping. There was no band to play us aboard. The only sound, other than groans, was the clanking of tin cups and water bottles as we clambered awkwardly up the gangplank under the weight of our duffle bags and useless desert kit. From childhood, I had been a fan of the comedy team Laurel and Hardy, and to me, our ascent up the gangplank, with all our paraphernalia, was a scene right out of their movie Beau Hunks, when they boarded a ship to Morocco as Foreign Legionnaires.

This was the end of my year on the desert squadron. I was leaving behind the Land of the Pharaohs, with memories of experiences that, even in my wildest dreams, I could never have imagined.

* It took seventy days for supplies and reinforcements via the Cape and Red Sea route to reach Egypt, which was entirely insufficient. In July-August 1940, construction began to turn the existing airfield at Takoradi into the much larger base required for reception and transit of aircraft and all sorts of material. The passenger and mail route established in the thirties, running from Takoradi to Khartoum, was greatly expanded, with staging bases at Lagos, Kano, Maiduguri, and Fort Lamy. It was a six-day, 3,697-mile journey. The last leg, from Khartoum to Abu Sueir, Egypt, was 1,026 miles. Altogether, this was a punishing and monotonous route in the backwater of the war.