Robert Hooke: the study of microscopy and the publication of Micrographia – Hooke’s study of the wave theory of light – Hooke’s law of elasticity – John Flamsteed and Edmond Halley: cataloguing stars by telescope – Newton’s early life – The development of calculus – The wrangling of Hooke and Newton – Newton’s Principia Mathematica: the inverse square law and the three laws of motion – Newton’s later life – Hooke’s death and the publication of Newton’s Opticks

The three people who between them established both the scientific method itself and the pre-eminence of British science at the end of the seventeenth century were Robert Hooke, Edmond Halley and Isaac Newton. It is some measure of the towering achievements of the other two that Halley clearly ranks third out of the trio in terms of his direct contribution to science; but in spite of the Newton bandwagon that has now been rolling for 300 years (and was given its initial push by Newton himself after Hooke had died), it is impossible for the unbiased historian to say whether Newton or Hooke made the more significant contribution. Newton was a loner who worked in isolation and established the single, profound truth that the Universe works on mathematical principles; Hooke was a gregarious and wide-ranging scientist who came up with a dazzling variety of new ideas, but also did more than anyone else to turn the Royal Society from a gentlemen’s gossip shop into the archetypal scientific society. His misfortune was to incur the enmity of Newton, and to die before Newton, giving his old enemy a chance to rewrite history – which he did so effectively that Hooke has only really been rehabilitated in the past few decades. Partly to put Newton in his place, but also because Hooke was the first of the trio to be born, I will start with an account of his life and work, and introduce the other two in the context of their relationships with Hooke.

Robert Hooke was born on the stroke of noon on 18 July 1635, seven years before Galileo Galilei died. His father, John Hooke, was curate of the Church of All Saints at Freshwater, on the Isle of Wight; this was one of the richest livings on the island, but the chief beneficiary was the Rector, George Warburton. As a mere curate, John Hooke was far from wealthy, and he already had two other children, Katherine, born in 1628, and John, born in 1630. Robert Hooke’s elder brother became a grocer in Newport, where he served as Mayor at one time, but hanged himself at the age of 46 – we do not know exactly why. His daughter Grace, Robert’s niece, would feature strongly in Robert’s later life.

Robert Hooke: the study of microscopy and the publication of Micrographia

Robert Hooke was a sickly child who was not expected to live. We are told that for the first seven years of his life he lived almost entirely on milk and milk products, plus fruit, with ‘no Flesh in the least agreeing with his weak Constitution’.1 But although small and slight and lacking in physical strength, he was an active boy who enjoyed running and jumping. It was only later, at about the age of 16, that he developed a pronounced malformation of his body, some sort of twist, which he later attributed to long hours spent hunched-over working at a lathe and with other tools. He became very skilful at making models, including a model ship about a metre long, complete with working rigging and sails; and after seeing an old brass clock taken to pieces he made a working clock out of wood.

Initially because of his ill health, Hooke’s formal education was neglected. When it seemed there was a chance of him surviving after all, his father began to teach him the rudiments of education, intending him to have a career in the church. But Robert’s continuing ill health and his father’s own growing infirmity meant that little progress was made and Robert continued to be left largely to his own devices. When a professional artist visited Freshwater to undertake a commission, Hooke took one look at how he set about his work and decided that he could do that, so after first making his own paints he set about copying any paintings that he could find, with sufficient skill that it was thought he might become a professional painter himself. When Robert’s father John Hooke died in 1648, after a long illness, Robert was 13 years old. With an inheritance of £100 he was sent to London to be apprenticed to the artist Sir Peter Lely. Robert first decided that there was not much point in using the money for an apprenticeship since he reckoned he could learn painting by himself, then found that the smell of the paints gave him severe headaches. Instead of becoming an artist, he used the money to pay for an education at Westminster School, where as well as his academic studies, he learnt to play the organ.

Although he was too young to be involved directly in the Civil War, the repercussions of the conflict did affect Hooke. In 1653, he secured a place at Christ Church College in Oxford as a chorister – but since the puritanical Parliament had done away with such frippery as church choirs, this meant that he had in effect got a modest income – a scholarship – for nothing. One of his contemporaries at Oxford, a man with a keen interest in science, was Christopher Wren, three years older than Hooke and another product of Westminster School. Like many other poor students at the time, Hooke also helped to make ends meet by working as servant to one of the wealthier undergraduates. At this time, many of the Gresham College group had been moved to Oxford by Oliver Cromwell to replace academics tarred with the brush of Oxford’s support for the Royalist side in the war, and Hooke’s skill at making things and carrying out experiments made him invaluable as an assistant to this group of scientists. He soon became both Robert Boyle’s chief (paid) assistant and his lifelong friend. Hooke was largely responsible for the success of Boyle’s air pump, and therefore for the success of the experiments carried out with it, and was also closely involved in the chemical work Boyle carried out in Oxford. But Hooke also carried out astronomical work for Seth Ward, the Savilian professor of astronomy at the time (inventing, among other things, improved telescopic sights), and in the mid-1650s he worked out ways to improve the accuracy of clocks for astronomical timekeeping.

Through this work, Hooke came up with the idea of a new kind of pocket watch regulated by a balance spring. This could have been the forerunner of the kind of chronometer that would have been accurate and dependable enough to determine longitude at sea, and Hooke claimed to have worked out how to achieve this. But when (without revealing all his secrets) he discussed the possibility of patenting such a device, negotiations broke down because Hooke objected to a clause in the patent allowing other people to reap the financial benefits of any improvements to his design. He never did reveal the secret of his idea, which died with him. But the pocket watch itself, although no sea-going chronometer, was a significant improvement on existing designs (Hooke gave one of these watches to Charles II, who was well pleased), which would alone have ensured him a place in the history books.

When the Royal Society was established in London in the early 1660s, it needed a couple of permanent staff members, a Secretary to look after the administrative side and a Curator of Experiments to look after the practical side. On the recommendation of Robert Boyle, the German-born Henry Oldenburg got the first job and Robert Hooke the second. Oldenburg hailed from Bremen, where he had been born in 1617, had been that city’s representative in London in 1653 and 1654, where he met Boyle and other members of his circle, and was for a time the tutor to one of Boyle’s nephews, Lord Dungarvan. His interest in science stirred, Oldenburg became a tutor in Oxford in 1656 and was very much a member of the circle from which the first Fellows of the Royal Society were drawn. He was fluent in several European languages and acted as a kind of clearing house for scientific information, communicating by letter with scientists all over Europe. He got on well with Boyle, becoming his literary agent and translating Boyle’s books, but unfortunately he took a dislike to Hooke. He died in 1677.

Hooke left Oxford to take up his post with the Royal in 1662; he had never completed his degree, because of his involvement as an assistant to Boyle and others, but in 1663 he was appointed MA anyway and also elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society. Two years later, his position as curator of experiments was changed from that of a servant employed by the Society to a position held by him as a Fellow and a member of the Council of the Society, an important distinction which marked his recognition as a gentleman supposedly on equal footing with the other Fellows, but which still (as we shall see) left him with a huge burden of duties. The honours were all very well, but to the impoverished Hooke his salary was just as important; unfortunately, the Royal was, in its early days, both disorganized and short of funds, and for a time Hooke was only kept afloat financially by the generosity of Robert Boyle. In May 1664, Hooke was a candidate for the post of professor of geometry at Gresham College, but lost out on the casting vote of the Lord Mayor. After considerable wrangling, it turned out that the Lord Mayor was not entitled to vote on the appointment, and in 1665 Hooke took over the post, which he retained for the rest of his life. At the beginning of the year he finally took up the appointment, and at the age of 29, Hooke also published his greatest work, Micrographia. Unusually for the time, it was written in English, in a very clear and readable style, which ensured that it reached a wide audience, but which may have misled some people into a lack of appreciation of Hooke’s scientific skill, since the way he presented his work made it seem almost easy.

14. A louse. From Hooke’s Micrographia, 1664.

As its title suggests, Micrographia was largely concerned with microscopy (the first substantial book on microscopy by any major scientist), and it is no exaggeration to say that it was as significant in opening the eyes of people to the small-scale world as Galileo’s The Starry Messenger was in opening the eyes of people to the nature of the Universe at large. In the words of Geoffrey Keynes, it ranks ‘among the most important books ever published in the history of science’. Samuel Pepys records how he sat up reading the volume until 2 am, calling it ‘the most ingenious book that ever I read in my life’.2

Hooke was not the first microscopist. Several people had followed up Galileo’s lead by the 1660s and, as we have seen, Malpighi in particular had already made important discoveries, especially those concerning the circulation of the blood, with the new instrument. But Malpighi’s observations had been reported piece by piece to the scientific community more or less as they had been made. The same is largely true of Hooke’s contemporary Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723), a Dutch draper who had no formal academic training but made a series of astounding discoveries (mostly communicated through the Royal Society) using microscopes that he made himself. These instruments consisted of very small, convex lenses (some the size of pinheads) mounted in strips of metal and held close to the eye – they were really just incredibly powerful magnifying glasses, but some could magnify 200 or 300 times. Van Leeuwenhoek’s most important discovery was the existence of tiny moving creatures (which he recognized as forms of life) in droplets of water – microorganisms including varieties now known as protozoa, rotifera and bacteria. He also discovered sperm cells (which he called ‘animalcules’), which provided the first hint at how conception works, and independently duplicated some of Malpighi’s work (which he was unaware of) on red blood cells and capillaries. These were important studies, and the romance of van Leeuwenhoek’s role as a genuine amateur outside the mainstream of science has assured him of prominence in popular accounts of seventeenth-century science (some of which even credit him with inventing the microscope). But he was a one-off, using unconventional techniques and instruments, and Hooke represents the mainstream path along which microscopy developed, following his own invention of improved compound microscopes using two or more lenses to magnify the objects being studied. He also packaged his discoveries in a single, accessible volume, and provided it with beautifully drawn and scientifically accurate drawings of what he had seen through his microscopes (many of the drawings were made by his friend Christopher Wren). Micrographia really did mark the moment when microscopy came of age as a scientific discipline.

The most famous of the microscopical discoveries reported by Hooke in his masterpiece was the ‘cellular’ structure of slices of cork viewed under the microscope. Although the pores that he saw were not cells in the modern biological meaning of the term, he gave them that name, and when what we now call cells were identified in the nineteenth century, biologists took over the name from Hooke. He also described the structure of feathers, the nature of a butterfly’s wing and the compound eye of the fly, among many observations of the living world. In a far-sighted section of the book he correctly identifies fossils as the remains of once-living creatures and plants. At that time, there was a widespread belief that these stones that looked like living things were just that – rocks, which, through some mysterious process, mimicked the appearance of life. But Hooke crushingly dismissed the notion that fossils were ‘Stones form’d by some extraordinary Plastick virtue latent in the Earth itself,’ and argued persuasively (referring to the objects now known as ammonites) that they were ‘the Shells of certain Shelfishes, which, either by some Deluge, Inundation, Earthquake, or some such other means, came to be thrown to that place, and there to be filled with some kind of mud or clay, or petrifying water, or some other substance, which in tract of time has been settled together and hardened.’ In lectures given at Gresham College around this time, but not published until after his death, Hooke also specifically recognized that this implied major transformations in the surface of the Earth. ‘Parts which have been sea are now land,’ he said, and ‘mountains have been turned into plains, and plains into mountains, and the like.’

Hooke’s study of the wave theory of light

Any of this would have been enough to make Hooke famous and delight readers such as Samuel Pepys. But there was more to Micrographia than microscopy. Hooke studied the nature of the coloured patterns produced by thin layers of material (such as the colours of an insect’s wing, or the rainbow pattern familiar today from oil or petrol spilled on water), and suggested that it was caused by some form of interference between light reflected from the two sides of the layer. One of the phenomena Hooke investigated in this way concerned coloured rings of light produced where two pieces of glass meet at a slight angle; in the classic form of the experiment, a convex lens rests on a piece of flat glass, so that there is a slight wedge-shaped air gap between the two glass surfaces near the point where they touch. The rings are seen by looking down on the lens from above, and the phenomenon is related to the way a thin layer of oil on water produces a swirling pattern of colours. It is a sign of how successful Newton was in rewriting history that this phenomenon became known as ‘Newton’s rings’. Hooke’s ideas about light were based on a wave theory, which he later developed to include the suggestion that the waves might be a transverse (side to side) oscillation, not the kind of push–pull waves of compression envisaged by Huygens. He described experiments involving combustion, from which he concluded that both burning and respiration involved something from the air being absorbed, coming very close to the discovery of oxygen (a century before it was actually discovered), and he made a clear distinction between heat, which he said arose in a body from ‘motion or agitation of its parts’ (almost two centuries ahead of his time!), and combustion, which involved two things combining. Hooke experimented on himself, sitting in a chamber from which air was pumped out until he felt pain in his ears, and was involved in the design and testing of an early form of diving bell. He invented the now-familiar ‘clock face’ type of barometer, a wind gauge, an improved thermometer and a hygroscope for measuring moisture in the air, becoming the first scientific meteorologist and noting the link between changes in atmospheric pressure and changes in the weather. As a bonus, Hooke filled a space at the end of the book with drawings based on some of his astronomical observations. And he spelled out with crystal clarity the philosophy behind all of his work, the value of ‘a sincere hand, and a faithful eye, to examine, and to record, the things themselves as they appear’, rather than relying on ‘work of the brain and the fancy’ without any grounding in experiment and observation. ‘The truth is,’ wrote Hooke, ‘the science of Nature has been already too long made only a work of the brain and the fancy: It is now high time that it should return to the plainness and soundness of observations on material and obvious things.’

John Aubrey, who knew Hooke, described him in 1680 as:

But of middling stature, something crooked, pale faced, and his face but little belowe, but his head is lardge; his eie full and popping, and not quick; a grey eie. He has a delicate head of haire, browne, and of an excellent moist curle. He is and ever was very temperate, and moderate in dyet, etc.

As he is of prodigious inventive head, so is [he] a person of great vertue and goodness.

Several factors conspired to prevent Hooke building on the achievements described in Micrographia to the extent that he might have done. The first was his position at the Royal Society, where he kept the whole thing going by carrying out experiments (plural) at every weekly meeting, some of them at the behest of other Fellows, some of his own design. He also read out papers submitted by Fellows who were not present, and described new inventions. Page after page of the minutes of the early years of the Royal contain variations on the themes of ‘Mr Hooke produced…’, ‘Mr Hooke was ordered…’, ‘Mr Hooke remarked…’, ‘Mr Hooke made some experiments…’, and so on and on. As if that were not enough to have on his plate (and remember that Hooke was giving full courses of lectures at Gresham College as well), when Oldenburg died in 1677, Hooke replaced him as one of the Secretaries of the Royal (although at least by that time there was more than one Secretary to share the administrative load), but gave up that post in 1683.

In the short term, soon after the publication of Micrographia, plague interrupted the activities of the Royal Society and, like many other people, Hooke retreated from London to the countryside, where he took refuge as a guest at the house of the Earl of Berkeley at Epsom. In the medium term, Hooke was distracted from his scientific work for years following the fire of London in 1666, when he became one of the principal figures (second only to Christopher Wren) in the rebuilding of the city; many of the buildings attributed to Wren are at least partially Hooke’s design, and in most cases it is impossible to distinguish between their contributions.

The fire took place in September 1666. In May that year, Hooke had read a paper to the Royal in which he discussed the motion of the planets around the Sun in terms of an attractive force exerted by the Sun to hold them in their orbits (instead of Cartesian whirlpools in the aether), similar to the way a ball on a piece of string can be held ‘in orbit’ by the force exerted by the string if you whirl it round and round your head. This was a theme that Hooke returned to after his architectural and surveying work on the rebuilding of London, and in a lecture given in 1674 he described his ‘System of the World’ as follows:

First, that all Coelestial Bodies whatsoever, have an attraction or gravitating power towards their own Centers, whereby they attract not only their own parts, and keep them from flying from them…but that they do also attract all the other Coelestial Bodies that are within the sphere of their activity…The second supposition is this, That all bodies whatsoever that are put into a direct and simple motion, will so continue to move forward in a streight line, till they are by some other effectual powers deflected and bent into a Motion, describing a Circle, Ellipsis, or some other more compounded Curve Line. The third supposition is, That these attractive powers are so much the more powerful in operating, by how much the nearer the body wrought upon is to their own Centers.3

The second of Hooke’s ‘suppositions’ is essentially what is now known as Newton’s first law of motion; the third supposition wrongly suggests that gravity falls off as one over the distance from an object, not one over the distance squared, but Hooke himself would soon rectify that misconception.

It is almost time to introduce Halley and Newton and their contributions to the debate about gravity. First, though, a quick skim through the rest of Hooke’s life.

Hooke’s law of elasticity

We know a great deal about Hooke’s later life from a diary which he started to keep in 1672. This is no work of literature, like Pepys’ diary, but a much more telegraphic record of day-to-day facts. But it describes almost everything about Hooke’s private life in his rooms at Gresham College, with such candour that it was felt unsuitable for publication until the twentieth century (one of the reasons why Hooke’s character and achievements did not receive full recognition until recently). Although he never married, Hooke had sexual relationships with several of his maidservants, and by 1676 his niece Grace, who was probably 15 at that time and had been living with him since she was a child, had become his mistress. He was devastated when she died in 1687, and throughout the rest of his life was noticeably melancholic; 1687 was also a key year in the dispute with Newton, which can hardly have helped matters. On the scientific side, apart from the work on gravity, in 1678 Hooke came up with his best-known piece of work, the discovery of the law of elasticity which bears his name. It is typical of the way history has treated Hooke that this rather dull piece of work (a stretched spring resists with a force proportional to its extension) should be known as Hooke’s Law, while his many more dazzling achievements (not all of which I have mentioned) are either forgotten or attributed to others. Hooke himself died on 3 March 1703, and his funeral was attended by all the Fellows of the Royal Society then present in London. The following year, Isaac Newton published his epic work on light and colour, Opticks, having deliberately sat on it for thirty years, waiting for Hooke to die.

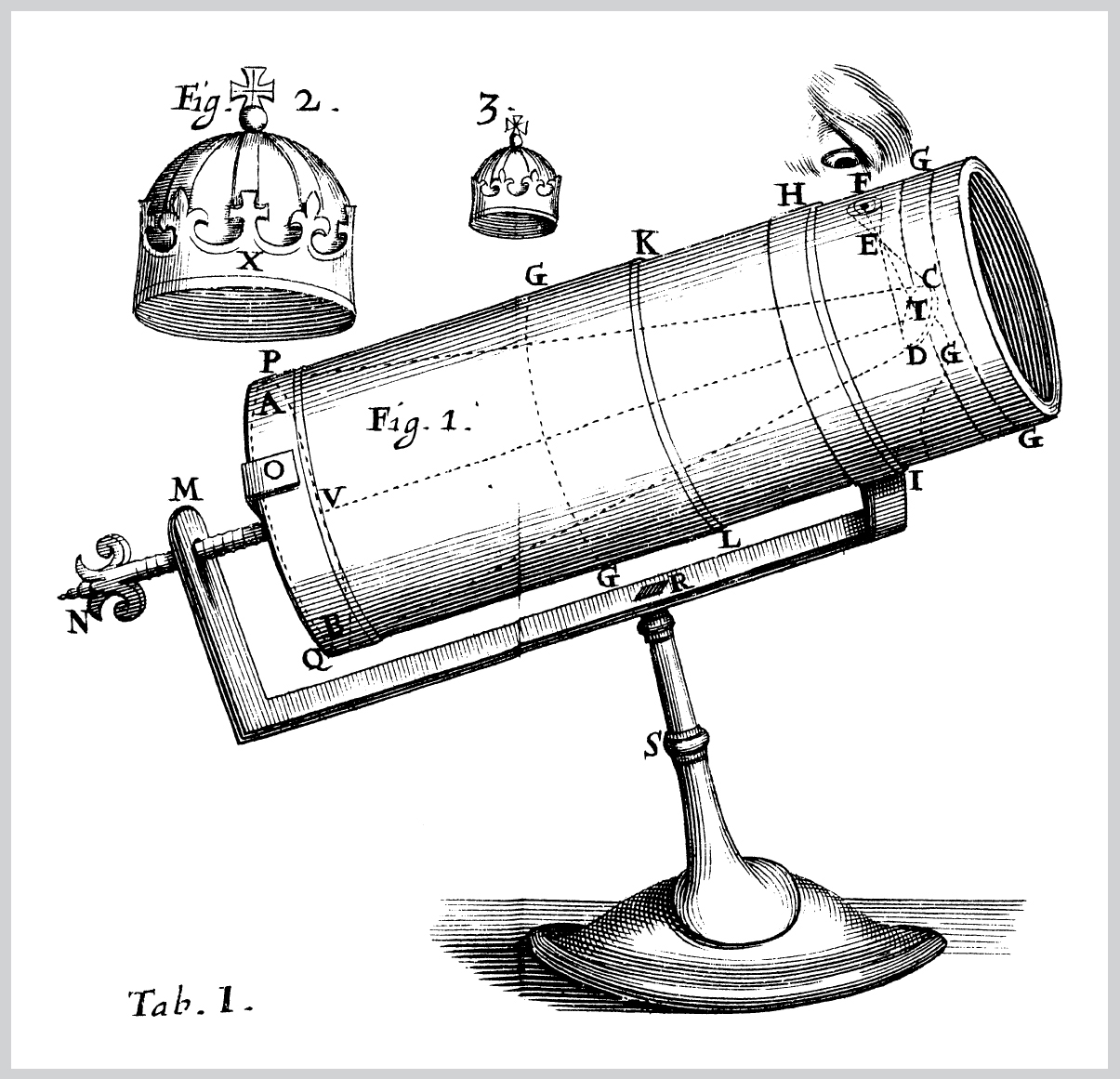

15. Newton’s telescope. From Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 1672.

Newton’s hostility to Hooke (I would have said monomaniacal hostility, but he felt the same way about other people, too) dated back to the early 1670s, when he was a young professor in Cambridge and first came to the attention of the Royal Society. In the 1660s, Newton (who was seven years younger than Hooke) completed his undergraduate studies in Cambridge, then became first a Fellow of Trinity College and, in 1669, the Lucasian professor of mathematics. The chair was in succession to Isaac Barrow, the first Lucasian professor, who resigned allegedly in order to spend more time at religious studies but who soon became Royal Chaplain and then Master of Trinity College, so may have had an ulterior motive. During all this time, Newton had been carrying out experiments and thinking about the world more or less on his own, hardly discussing his ideas with anyone at all. Among other things, he studied the nature of light, using prisms and lenses. In his most important optical work, he split white light (actually sunlight) up into the rainbow colours of the spectrum using a prism, then recombined the colours to make white light again, proving that white light was just a mixture of all the colours of the rainbow.

Previously, other people (including Hooke) had passed white light through a prism and cast the beam on a screen a few inches away, producing a white blob of light with coloured edges. Newton was able to go further because he used a pinhole in a window blind as his source of light and cast the beam from the prism on to a wall on the other side of a large room, many feet away, giving a bigger distance for the colours to spread out. From this work, his interest in colours led him to consider the problem of the coloured fringes produced around the edges of the images seen through telescopes built around lenses, and he designed and built a reflecting telescope (unaware of the earlier work of Leonard Digges) which did not suffer from this problem.

News of all this began to break when Newton described some of his work on light in the lectures he gave as Lucasian professor, and from visitors to Cambridge who either saw or heard about the telescope. The Royal Society asked to see the instrument, and late in 1671 Isaac Barrow took one (Newton probably made at least two) to London and demonstrated it at Gresham College. Newton was immediately elected a Fellow (the actual ceremony took place on 11 January 1672) and was asked what else he had up his sleeve. His response was to submit to the society a comprehensive paper on light and colours. It happened that Newton favoured the corpuscular theory of light as a stream of particles, but the discoveries he spelled out at this time held true regardless of whether this model or the wave model (favoured by people such as Huygens and Hooke) was used to try to explain them.

From several sidelong remarks in the paper, not least a statement that Newton started to experiment in optics in 1666, it seems clear that the trigger for his interest in light had been reading Hooke’s Micrographia, but he played this down by making reference to ‘an unexpected experiment, which Mr Hook, somewhere in his Micrography, reported to have made with two wedge-like transparent vessels’ rather than going into details of Hooke’s work (in this example, on what became known as Newton’s rings).

Hooke, an older and well-established scientist, was decidedly miffed at receiving less credit from the young whipper-snapper than he thought he was due, and said as much to his friends. Hooke was always touchy about receiving proper recognition for his work, understandably so in view of his own humble origins and his recent past as a servant to the learned gentleman who established the Royal Society.4 Newton, though, even at this early age, had the highest opinion of his own abilities (largely justified, but still not an appealing characteristic) and regarded other scientists, no matter how respectable and well established, as scarcely fit to lick his boots. This attitude was reinforced over the next few years, when a succession of critics, clearly Newton’s intellectual inferiors, raised a host of quibbles about his work, which showed their own ignorance more than anything else. At first Newton tried to answer some of the more reasonable points raised, but eventually he became infuriated at the time-wasting and wrote to Oldenburg: ‘I see I have made myself a slave to philosophy…I will resolutely bid adieu to it eternally, except what I do for my private satisfaction, or leave it to come after me; for I see a man must either resolve to put out nothing new, or become a slave to defend it.’

When Oldenburg mischievously reported an exaggerated account of Hooke’s views to Newton, deliberately trying to stir up trouble, he succeeded better than he could have expected. Newton replied, thanking Oldenburg ‘for your candour in acquainting me with Mr Hook’s insinuations’ and asking for an opportunity to set the record straight. J. G. Crowther has neatly summed up the real root of the problem, which Oldenburg fanned into flame: ‘Hooke could not understand what tact had to do with science…Newton regarded discoveries as private property’.5 At least, he did so when they were his discoveries. After four years, the very public washing of dirty linen resulting from this personality clash had to be brought to an end or the Royal Society would become a laughing stock, and several Fellows got together to insist, through Oldenburg (who must have been unhappy to have his fun at Hooke’s expense brought to a close), on a public reconciliation (whatever the two protagonists thought in private), which was achieved through an exchange of letters.

Hooke’s letter to Newton seems to bear the genuine stamp of his personality, always ready to argue about science in a friendly way (preferably among a few companions in one of the fashionable coffee houses), but really only interested in the truth:

I judge you have gone farther in that affair [the study of light] than I did…I believe the subject cannot meet with a fitter and more able person to enquire into it than yourself, who are in every way fitted to complete, rectify, and reform what were the sentiments of my younger studies, which I designed to have done somewhat at myself, if my other more troublesome employments would have permitted, though I am sufficiently sensible it would have been with abilities much inferior to yours. Your design and mine, are, I suppose, both at the same thing, which is the discovery of truth, and I suppose we can both endure to hear objections, so as they come not in a manner of open hostility, and have minds equally inclined to yield to the plainest deductions of reason from experiment.

There speaks a true scientist. Newton’s reply, although it could be interpreted as conciliatory, was totally out of character, and carries a subtext which is worth highlighting. After saying that ‘you defer too much to my ability’ (a remark Newton would never have made to anyone except under duress), he goes on with one of the most famous (and arguably most misunderstood) passages in science, usually interpreted as a humble admission of his own minor place in the history of science:

What Des-Cartes did was a good step. You have added much in several ways, & especially in taking ye colours of thin plates into philosophical consideration. If I have seen farther, it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.

John Faulkner, of the Lick Observatory in California, has suggested an interpretation of these remarks which flies in the face of the Newton legend, but closely matches Newton’s known character. The reference to Descartes is simply there to put Hooke in his place by suggesting that the priority Hooke claims actually belongs to Descartes. The second sentence patronizingly gives Hooke (the older and more established scientist, remember) a little credit. But the key phrase is the one about ‘standing on the shoulders of Giants’. Note the capital letter. Even granted the vagaries of spelling in the seventeenth century, why should Newton choose to emphasize this word? Surely, because Hooke was a little man with a twisted back. The message Newton intends to convey is that although he may have borrowed from the Ancients, he has no need to steal ideas from a little man like Hooke, with the added implication that Hooke is a mental pygmy as well as a small man physically. The fact that the source of this expression predates Newton and was picked up by him for his own purposes only reinforces Faulkner’s compelling argument. Newton was a nasty piece of work (for reasons that we shall go on to shortly) and always harboured grudges. True to his word to Oldenburg, he did go into his shell and largely stop reporting his scientific ideas after this exchange in 1676. He only properly emerged on to the scientific stage again, to produce the most influential book in the history of science, after some cajoling by the third member of the triumvirate that transformed science at this time, Edmond Halley.

John Flamsteed and Edmond Halley: cataloguing the stars by telescope

Halley, the youngest of the three, was born on 29 October 1656 (this was on the Old Style Julian calendar still in use in England then; it corresponds to 8 November on the modern Gregorian calendar), during the Parliamentary interregnum. His father, also called Edmond, was a prosperous businessman and landlord who married his mother, Anne Robinson, in a church ceremony only seven weeks before the birth. The most likely explanation for this is that there had been an earlier civil ceremony, of which no record has survived, and that the imminent arrival of their first child encouraged the couple to exchange religious vows as well; it was fairly common practice at the time to have a civil ceremony first and a church ceremony later (if at all). Edmond had a sister Katherine, who was born in 1658 and died in infancy, and a brother Humphrey, whose birth date is not known, but who died in 1684. Little is known about the details of Halley’s early life, except that in spite of some financial setbacks resulting from the fire of London in 1666, his father was comfortably able to provide young Edmond with the best available education, first at St Paul’s School in London (the family home was in a peaceful village just outside London, in what is now the borough of Hackney) and then at Oxford University. By the time he arrived at Queen’s College in July 1673, Halley was already a keen astronomer who had developed his observational skills using instruments paid for by his father; he arrived in Oxford with a set of instruments that included a telescope 24 feet (about 7.3 metres) long and a sextant 2 feet (60 centimetres) in diameter, as good as the equipment used by many of his contemporary professional astronomers.

Several events around that time would have a big impact on Halley’s future life. First, his mother had died in 1672. No details are known, but she was buried on 24 October that year. The repercussions for Halley would come later, as a result of his father’s second marriage. Then, in 1674, the Royal Society decided that it ought to establish an observatory to match the Observatoire de Paris, which had just been founded by the French Academy. The urgency of the proposal was highlighted by a French claim that the problem of finding longitude at sea had been solved by using the position of the Moon against the background stars as a kind of clock to measure time at sea. The claim proved premature – although the scheme would work in principle, the Moon’s orbit is so complicated that by the time the necessary tables of its motion could be compiled, accurate chronometers had provided the solution to the longitude problem. The astronomer John Flamsteed (who lived from 1646 to 1719) was asked to look into the problem, and correctly concluded that it would not work because neither the position of the Moon nor the positions of the reference stars were known accurately enough. When Charles II heard the news, he decided that, as a seafaring nation, Britain had to have the necessary information as an aid to navigation, and the planned observatory became a project of the Crown. Flamsteed was appointed ‘Astronomical Observator’ by a royal warrant issued on 4 March 1675 (the first Astronomer Royal) and the Royal Observatory was built for him to work in, on Greenwich Hill (a site chosen by Wren). Flamsteed took up residence there in July 1676 and was elected as one of the Fellows of the Royal Society in the same year.

In 1675, the undergraduate Edmond Halley began a correspondence with Flamsteed, initially writing to describe some of his own observations which disagreed with some published tables of astronomical data, suggesting the tables were inaccurate, and asking Flamsteed if he could confirm Halley’s results. This was music to Flamsteed’s ears, since it confirmed that modern observing techniques could improve on existing stellar catalogues. The two became friends, and Halley was something of Flamsteed’s protégé for a time – although, as we shall see, they later fell out. In the summer of that year, Halley visited Flamsteed in London, and he assisted him with observations, including two lunar eclipses on 27 June and 21 December. After the first of these observations, Flamsteed wrote in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society that ‘Edmond Halley, a talented young man of Oxford was present at these observations and assisted carefully with many of them.’ Halley published three scientific papers in 1676, one on planetary orbits, one on an occultation of Mars by the Moon observed on 21 August that year and one on a large sunspot observed in the summer of 1676.6 He was clearly a rising star of astronomy. But where could he best make a contribution to the subject?

Flamsteed’s primary task at the new Royal Observatory was to make an accurate survey of the northern skies, using modern telescopic sights to improve the accuracy of old catalogues which used so-called open sights (the system used by Tycho), where the observer looked along a rod pointing at the chosen star. With telescopic sites, a fine hair in the focal plane of the telescope provides a far more accurate guide to the precise alignment of a star. Impatient to make a name and a career for himself, Halley hit on the idea of doing something similar to Flamsteed’s survey for the southern skies, but concentrating on just the brightest couple of hundred stars to get results reasonably quickly. His father supported the idea, offering Halley an allowance of £300 a year (three times Flamsteed’s salary as Astronomer Royal), and promising to cover many of the expenses of the expedition. Flamsteed and Sir Jonas Moore, the Surveyor General of the Ordnance, recommended the proposal to the King, who arranged free passage with the East India Company for Halley, his equipment and a friend, James Clerke, to the Island of St Helena, at that time the most southerly British possession (this was almost a hundred years before James Cook landed in Botany Bay in 1770). They sailed in November 1676, with Halley, now just past his twentieth birthday, abandoning his degree studies.

The expedition was a huge scientific success (in spite of the foul weather Halley and Clerke encountered on St Helena), and also seems to have given Halley an opportunity for some social life. Hints of sexual impropriety surround Halley’s early adult life, and in his Brief Lives, John Aubrey (who lived from 1626 to 1697, and who not only knew Newton but knew people who had met Shakespeare, but is admittedly not always to be relied on) mentions a long-married but childless couple who travelled out to St Helena in the same ship as Halley. ‘Before he came [home] from the Island,’ writes Aubrey, ‘she was brought to bed of a Child.’ Halley seems to have mentioned this event as a curious benefit of the sea voyage or the air in St Helena on the childless couple; Aubrey implies that Halley was the father of the child. This was the kind of rumour that would dog the young man for several years.

Halley came home in the spring of 1678 and his catalogue of southern stars was published in November that year, earning him the sobriquet ‘Our Southern Tycho’ from Flamsteed himself; he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society on 30 November. As well as his stellar cataloguing, Halley had observed a transit of Mercury across the face of the Sun while he was in St Helena. In principle, this provided a way to calculate the distance to the Sun by a variation on the theme of parallax, but these early observations were not accurate enough for the results to be definitive. Nevertheless, Halley had planted a seed that would bear fruit before too long. On 3 December, at the ‘recommendation’ of the King, Halley was awarded his MA (after becoming FRS), in spite of failing to complete the formal requirements for his degree. He was now a member, on equal terms, of the group that included Boyle, Hooke, Flamsteed, Wren and Pepys (Newton had by now retreated into his shell in Cambridge). And they had just the job for him.

16. Hevelius calculating star positions using a sextant. From Hevelius’s Machina Coelestis, 1673.

Because of its potential importance for navigation, the whole business of obtaining accurate star positions was of key importance in the late seventeenth century, both commercially and because of its military implications. But the main observing programme in the 1670s, an attempt to improve on Tycho’s catalogue, was being carried out in Danzig (now Gdansk) by a German astronomer who insisted on using the traditional open sights system of Tycho himself, albeit updated at great expense with new instruments, to the frustration of his contemporaries, particularly Hooke and Flamsteed. This backward-looking astronomer had been born in 1611, which perhaps explains his old-fashioned attitude, and christened Johann Höwelcke, but Latinized his name to Johannes Hevelius. In a correspondence beginning in 1668, Hooke implored him to switch to telescopic sights, but Hevelius stubbornly refused, claiming that he could do just as well with open sights. The truth is that Hevelius was simply too set in his ways to change and distrusted the new-fangled methods. He was like someone who persists in using an old-fashioned manual typewriter even though a modern word-processing computer is available.

One of the key features of Halley’s southern catalogue (obtained, of course, telescopically) was that it overlapped with parts of the sky surveyed by Tycho, so that by observing some of the same stars as Tycho, Halley had been able to key in his measurements to those of the northern sky, where Hevelius was now (in his own estimation) busily improving on Tycho’s data. When Hevelius wrote to Flamsteed at the end of 1678 asking to see Halley’s data, the Royal Society saw an opportunity to check up on Hevelius’s claims. Halley sent Hevelius a copy of the southern catalogue and said that he would be happy to use the new data from Hevelius instead of the star positions from Tycho to make the link between the northern and southern skies. But, of course, he would like to visit Danzig to confirm the accuracy of the new observations.

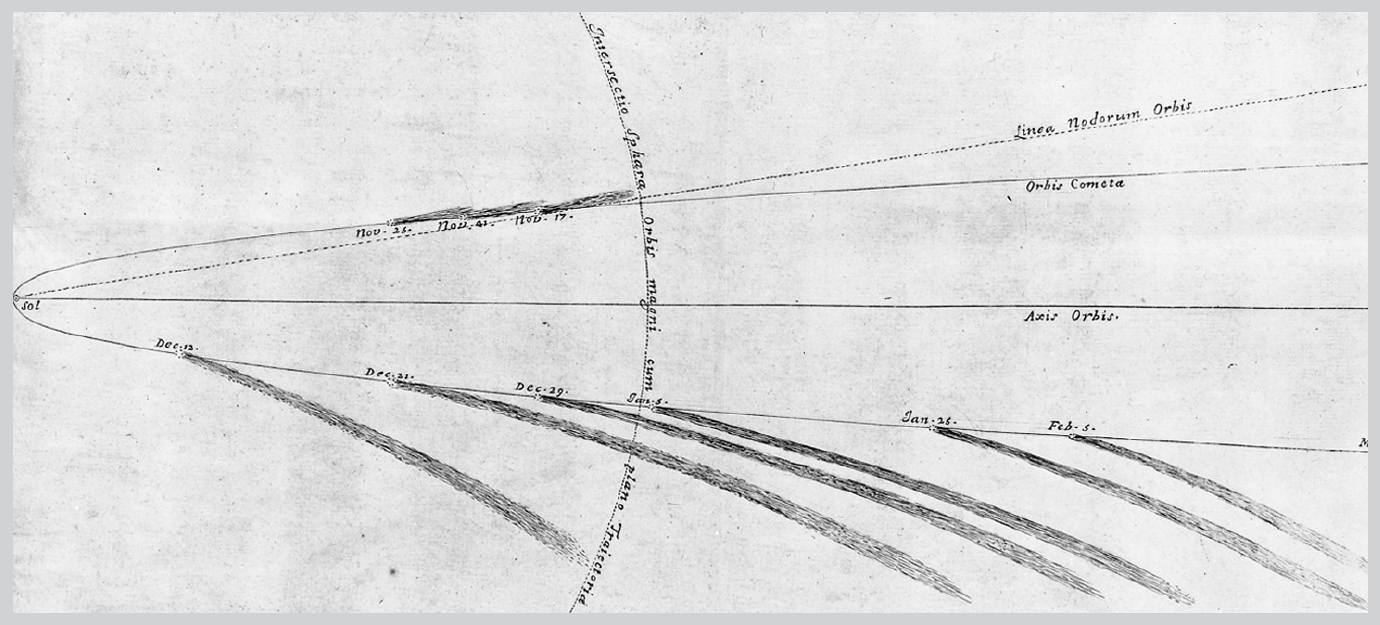

17. Newton’s sketch of the orbit of the comet seen in 1680.

So, in the spring of 1679, Halley set out to see if the incredible claims for accuracy that Hevelius, now aged 68, was making could be justified. Initially, Halley supported Hevelius’s claims, reporting back that his positions obtained with open sights really were as good as he claimed. But on his return to England, he eventually changed his tune and said that the telescopic observations were much better. Halley later claimed that he had only been tactful to Hevelius’s face, not wanting to hasten, the death of ‘an old peevish Gentleman’. In fact, Hevelius lived for another nine years, so he cannot have been that frail when Halley saw him. Gossip at the time, though, suggests there was more to the story.

Hevelius’s first wife had died in 1662, and in 1663 he had married a 16-year-old beauty, Elisabetha. When Halley visited Danzig, Hevelius was 68 and Elisabetha was 32. Halley was a handsome 22-year-old with a track record of sexual indiscretion. There may have been nothing in the inevitable rumours that followed Halley back to Britain, and there may be a perfectly respectable explanation for the fact that when news reached London later that year falsely reporting Hevelius’s death, Halley’s immediate reaction was to send the presumed widow a present of an expensive silk dress (at £6 8s 4d the cost of the dress amounted to the equivalent of three weeks’ salary for the Astronomer Royal, though merely a week of Halley’s allowance). But the kind of behaviour which made such rumours credible helped to create the rift between Flamsteed (a very serious-minded individual) and Halley, while Halley’s initial endorsement of Hevelius’s unrealistic claims certainly did not meet with his mentor’s approval.

Not that Halley seemed to care much about the prospects for his career in astronomy at this time. Having achieved so much so soon, like a pop star after the first wave of success he seems to have been content to sit back on his laurels and make the most of the good thing offered by his money (or rather, his father’s money). After returning from Danzig he spent more than a year basically just having a good time, attending meetings of the Royal but not contributing anything, visiting Oxford and hanging out in fashionable coffee houses, the equivalent of today’s trendy wine bars (he particularly favoured Jonathan’s in Change Alley). However, towards the end of this period, comets entered Halley’s life for the first time, although at first only in a minor way.

In the winter of 1680/81, a bright comet became visible. It was first seen in November 1680, moving towards the Sun before being lost in the Sun’s glare. It reappeared, going away from the Sun, a little later, and was at first thought to be two separate comets. Flamsteed was one of the first people to suggest that the phenomenon was really a single object, postulating that it had been repelled from the Sun by some sort of magnetic effect. It was a very prominent object in the night sky, clearly visible from the streets of London and Paris, the brightest comet that anyone alive at the time had ever seen. When it first appeared, Halley was about to embark on the typical wealthy young gentleman’s Grand Tour of Europe, accompanied by an old schoolfriend, Robert Nelson. They travelled to Paris in December (arriving on Christmas Eve), and saw the second appearance of the comet from the Continent. On his travels through France and Italy, Halley took the opportunity to discuss the comet (and other astronomical matters) with other scientists, including Giovanni Cassini. Robert Nelson stayed in Rome, where he fell in love with (and later married) the second daughter of the Earl of Berkeley (the one who had provided a refuge for Hooke from the plague). Halley made his way back to England via Holland as well as Paris, perhaps deviating from the usual dilettante Grand Tour, since by the time he arrived back in London on 24 January 1682 he had, in the words of Aubrey, ‘contracted an acquaintance and friendship with all the eminent mathematicians in France and Italy’.

Halley spent only a little over a year abroad, quite short for a Grand Tour in those days, and it may be that he hurried home because his father remarried around this time, although we don’t know the exact date of the wedding. It is an indication of how little we know abut Halley’s private life that his own wedding, which took place on 20 April 1682, comes completely out of the blue as far as any historical records are concerned. We know that Halley’s wife was Mary Tooke, and that the wedding took place in St James’ Church, in Duke Place, London. The couple were together (happily, it seems) for 50 years and had three children. Edmond junior was born in 1698, became a surgeon in the Navy and died two years before his father. Two daughters were born in the same year as each other, 1688, but were not twins. Margaret remained a spinster, but Catherine married twice. There were possibly other children who died in infancy. And that is essentially all we know about Halley’s family.

After his marriage Halley lived in Islington, and over the next two years carried out detailed observations of the Moon intended to provide (eventually) the essential reference data for the lunar method of finding longitude. This would require accurate observations over some 18 years, the time it takes for the Moon to complete one cycle of its wanderings against the background stars. But in 1684, Halley’s affairs were thrown into confusion by the death of his father and the project was abandoned for many years, as other matters took precedence.

Halley’s father walked out of his house on Wednesday 5 March 1684 and never returned. His naked body was found in a river near Rochester five days later. The official verdict was murder, but no murderer was ever found, and the evidence was also consistent with suicide. Halley senior died without leaving a will and with his wealth considerably reduced by the extravagance of his second wife. There was an expensive legal battle between Halley and his stepmother over the estate. Halley was certainly not plunged into abject poverty by these events – he had property of his own and his wife had brought a good dowry with her. But his circumstances were sufficiently altered that in January 1686 he gave up his Fellowship of the Royal Society in order to become the paid Clerk to the society – the rules laid down that paid servants of the Royal could not be Fellows. Only a need for money – albeit a temporary need – could have encouraged this course of action.

Like Halley’s private life, the European world was in turmoil in the middle of the 1680s. In France, the Edict of Nantes was revoked in 1685, while further afield Turkish forces reached the gates of Vienna, Buda and Belgrade around this time. In England, Charles II died and was succeeded by his Catholic brother, James II. And while all this was going on, Halley became involved with what is now regarded as the most important publication in the history of science, Isaac Newton’s Principia.

Back in January 1684, after a meeting of the Royal Society, Halley had fallen into conversation with Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke about planetary orbits. The idea of an inverse square law of attraction being behind the orbits of the planets was not new even then – it went back at least to 1673, when Christiaan Huygens had calculated the outward (centrifugal) force on an object travelling in a circular orbit, and speculation along these lines had been taken up by Hooke, as we shall see, in correspondence with Newton after 1674. Wren had also discussed these ideas with Newton, in 1677. The three Fellows agreed that Kepler’s laws of motion implied that the centrifugal force ‘pushing’ planets outwards from the Sun must be inversely proportional to the squares of their distances from the Sun, and that therefore, in order for the planets to stay in their orbits, they must be attracted by the Sun by an equivalent force which cancelled out the centrifugal force.

But was this an inevitable consequence of an inverse square law? Did such a law uniquely require that planets must follow elliptical orbits? Proving this mathematically was horrendously difficult using the traditional techniques available to them and Halley and Wren were willing to admit that the task was beyond them. Hooke, though, told the other two that he could derive all the laws of planetary motion starting out from the assumption of an inverse square law. The others were sceptical, and Wren offered to give Hooke a book to the value of 40 shillings if he could produce the proof in two months.

Hooke failed to produce his proof and the debate lapsed while Halley attended to the complicated business of sorting out his father’s affairs after the murder (or suicide). It was probably in connection with this that Halley visited relatives in Peterborough in the summer of 1684, and this in turn may be why he visited Newton in Cambridge in August that year – because he was in the area anyway. There is no evidence that this was any kind of official visit on behalf of the Royal Society (in spite of myths to that effect) and only circumstantial evidence that Halley made the visit because he was in the area on family business. But he had certainly corresponded with Newton about the comet, and may have met him in 1682, so it is natural that he should have taken an opportunity to visit Cambridge when it arose. Whatever, there is no doubt that when Halley did visit Newton they discussed planetary orbits and the inverse square law. Newton later told his mathematician friend Abraham De Moivre (a French Huguenot refugee) exactly what happened:

In 1684 Dr Halley came to visit him in Cambridge, after they had been some time together the Dr asked him what he thought the Curve would be that would be described by the Planets supposing the force of attraction towards the Sun to be reciprocal to the square of their distance from it. Sr Isaac replied immediately it would be an Ellipsis, the Dr struck with joy & amazement asked him how he knew it, why saith he, I have calculated it, whereupon Dr Halley asked him for the calculation without any further delay, Sr Isaac looked among his papers but could not find it, but he promised him to renew it, & then send it him.7

It was this encounter that led Newton to write the Principia, establishing his image as the greatest scientist who ever lived. But almost everything he described in that book had been done years before and kept hidden from public view until that happy encounter in Cambridge in 1684. This may seem hard to understand today, when scientists are almost too eager to rush their ideas into print and establish their priority, but when you look at Newton’s background and upbringing, his secretiveness is less surprising.

Newton’s early life

Isaac Newton came, on his father’s side, from a farming family that had just started to do well for themselves in a material way, but lacked any pretensions to intellectual achievement. His grandfather, Robert Newton, had been born some time around 1570 and had inherited farmland at Woolsthorpe, in Lincolnshire. He prospered from his farming so much that he was able to purchase the manor of Woolsthorpe in 1623, gaining the title of Lord of the Manor. Though not as impressive as it sounds to modern ears, this was a distinct step up the social ladder for the Newton family, and probably an important factor in enabling Robert’s son Isaac (born in 1606) to marry Hannah Ayscough, the daughter of James Ayscough, described in contemporary accounts as ‘a gentleman’. The betrothal took place in 1639. Robert made Isaac the heir to all his property, including the lordship of the manor, and Hannah brought to the union as her dowry property worth £50 per year. Neither Robert Newton nor his son Isaac ever learned to read or write, but Hannah’s brother William was a Cambridge graduate, a clergyman who enjoyed the living at the nearby village of Burton Coggles. The marriage between Isaac and Hannah took place in 1642, six months after the death of Robert Newton; six months after the wedding, Isaac also died, leaving Hannah pregnant with a baby who was born on Christmas Day and christened Isaac after his late father.

Many popular accounts note the coincidence that ‘the’ Isaac Newton was born in the same year, 1642, that Galileo died. But the coincidence rests on a cheat – using dates from two different calendar systems. Galileo died on 8 January 1642 according to the Gregorian calendar, which had already been introduced in Italy and other Catholic countries; Isaac Newton was born on 25 December 1642 according to the Julian calendar still used in England and other Protestant countries. On the Gregorian calendar, the one we use today, Newton was born on 4 January 1643, while on the Julian calendar Galileo died right at the end of 1641. Either way, the two events did not take place in the same calendar year. But there is an equally noteworthy and genuine coincidence that results from taking Newton’s birthday as 4 January 1643, in line with our modern calendar. In that case, he was born exactly 100 years after the publication of De Revolutionibus, which highlights how quickly science became established once it became part of the Renaissance.

Although the English Civil War disrupted many lives, as we have seen, over the next few years it largely passed by the quiet backwaters of Lincolnshire, and for three years Isaac Newton enjoyed the devoted attention of his widowed mother. But in 1645, just when he was old enough to appreciate this, she remarried and he was sent to live with his maternal grandparents. Almost literally ripped from his mother’s arms and dumped in more austere surroundings at such a tender age, this scarred him mentally for life, although no unkindness was intended. Hannah was just being practical.

Like most marriages among the families of ‘gentlemen’ at the time (including Hannah’s first marriage), this second marriage was a businesslike relationship rather than a love match. Hannah’s new husband was a 63-year-old widower, Barnabas Smith, who needed a new partner and essentially chose Hannah from the available candidates (he was the Rector of North Witham, less than 3 kilometres from Woolsthorpe). The business side of the arrangement included the settling of a piece of land on young Isaac by the Rector, on condition that he lived away from the new matrimonial home. So while Hannah went off to North Witham, where she bore two daughters and a son before Barnabas Smith died in 1653, Isaac spent eight formative years as a solitary child in the care of elderly grandparents (they had married back in 1609 and must have been almost as old as Hannah’s new husband), who seem to have been dutiful and strict, rather than particularly loving towards him.

The bad side of this is obvious enough, and clearly has a bearing on Isaac’s development as a largely solitary individual who kept himself to himself and made few close friends. But the positive side is that he received an education.8 Had his father lived, Isaac Newton would surely have followed in his footsteps as a farmer; but to the Ayscough grandparents it was natural to send the boy to school (one suspects not least because it kept him out of the way). Although Isaac returned to his mother’s house in 1653 when he was 10 and she was widowed for the second time, the seed had been sown, and when he was 12 he was sent to study at the grammar school in Grantham, about 8 kilometres from Woolsthorpe. While there, he lodged with the family of an apothecary, Mr Clark, whose wife had a brother, Humphrey Babington. Humphrey Babington was a Fellow of Trinity College in Cambridge, but spent most of his time at Boothby Pagnell, near Grantham, where he was rector.

Although Isaac seems to have been lonely at school, he was a good student and also showed an unusual ability as a model maker (echoing Hooke’s skill), constructing such devices (much more than mere toys) as a working model of a windmill and flying a kite at night with a paper lantern attached to it, causing one of the earliest recorded UFO scares. In spite of his decent education (mostly the Classics, Latin and Greek), Newton’s mother still expected him to take over the family farm when he became old enough, and in 1659 he was taken away from the school to learn (by practical experience) how to manage the land. This proved disastrous. More interested in books, which he took out to read in the fields, than in his livestock, Newton was fined several times for allowing his animals to damage other farmers’ crops, and many stories of his absent-mindedness concerning his agricultural duties have come down to us, doubtless embroidered a little over the years. While Isaac was (perhaps to some extent deliberately) demonstrating his incompetence in this area, Hannah’s brother William, the Cambridge graduate, was urging her to let the young man follow his natural inclinations and go up to the university. The combination of her brother’s persuasion and the mess Isaac was making of her farm won her grudging acceptance of the situation, and in 1660 (the year of the Restoration) Isaac went back to school to prepare for admission to Cambridge. On the advice of (and, no doubt, partly thanks to the influence of) Humphrey Babington, he took up his place at Trinity College on 8 July 1661. He was then 18 years old – about the age people go to university today, but rather older than most of the young gentlemen entering Cambridge in the 1660s, when it was usual to go up to the university at the age if 14 or 15, accompanied by a servant.

Far from having his own servant, though, Isaac had to act as a servant himself. His mother would not tolerate more than the minimum expenditure on what she still regarded as a wasteful indulgence, and she allowed Isaac just £10 a year, although her own income at this time was in excess of £700 a year. Being a student’s servant at this time (called a subsizar) could be extremely unpleasant and involve such duties as emptying the chamber pots of your master. It also had distinctly negative social overtones. But here Newton was lucky (or cunning); he was officially the student of Humphrey Babington, but Babington was seldom up at college and he was a friend who did not stress the master–servant relationship with Isaac. Even so, possibly because of his lowly status and certainly because of his introverted nature, Newton seems to have had a miserable time in Cambridge until early in 1663, when he met and became friendly with Nicholas Wickins. They were both unhappy with their room-mates and decided to share rooms together, which they did in the friendliest way for the next 20 years. It is quite likely that Newton was a homosexual; the only close relationships he had were with men, although there is no evidence that these relationships were consummated physically (equally, there is no evidence that they weren’t). This is of no significance to his scientific work, but may provide another clue to his secretive nature.

The scientific life began to take off once Newton decided pretty much to ignore the Cambridge curriculum, such as it was, and read what he wanted (including the works of Galileo and Descartes). In the 1660s, Cambridge was far from being a centre of academic excellence. Compared with Oxford it was a backwater and, unlike Oxford, had not benefited from any intimate contact with the Greshamites. Aristotle was still taught by rote, and the only thing a Cambridge education fitted anyone for was to be a competent priest or a bad doctor. But the first hint of what was to be came in 1663, when Henry Lucas endowed a professorship of mathematics in Cambridge – the first scientific professorship in the university (and the first new chair of any kind since 1540). The first holder of the Lucasian chair of mathematics was Isaac Barrow, previously a professor of Greek (which gives you some idea of where science stood in Cambridge at the time). The appointment was doubly significant – first because Barrow did teach some mathematics (his first course of lectures, in 1664, may well have been influential in stimulating Newton’s interest in science) and then, as we have seen, because of what happened when he resigned from the position five years later.

18. A page from Newton’s work.

According to Newton’s own later account, it was during those five years, from 1663 to 1668, that he carried out most of the work for which he is now famous. I have already discussed his work on light and colour, which led to the famous row with Hooke. But there are two other key pieces of work which need to be put in context – Newton’s invention of the mathematical techniques now known as calculus (which he called fluxions) and his work on gravity that led to the Principia.

Whatever the exact stimulus, by 1664 Newton was a keen (if unconventional) scholar and eager to extend his time at Cambridge. The way to do this was first to win one of the few scholarships available to an undergraduate and then to gain election, after a few years, to a Fellowship of the college. In April 1664, Newton achieved the essential first step, winning a scholarship in spite of his failure to follow the prescribed course of study, and almost certainly because of the influence of Humphrey Babington, by now a senior member of the college. The scholarship brought in a small income, provided for his keep and removed from him the stigma of being a subsizar; it also meant that after automatically receiving his BA in January 1665 (once you were up at Cambridge in those days it was impossible not to get a degree unless you chose, as many students did, to leave early), he could stay in residence, studying what he liked, until he became MA in 1668.

The development of calculus

Newton was an obsessive character who threw himself body and soul into whatever project was at hand. He would forget to eat or sleep while studying or carrying out experiments, and carried out some truly alarming experiments on himself during his study of optics, gazing at the Sun for so long he nearly went blind and poking about in his eye with a bodkin (a fat, blunt, large-eyed needle) to study the coloured images resulting from this rough treatment. The same obsessiveness would surface in his later life, whether in his duties at the Royal Mint or in his many disputes with people such as Hooke and Gottfried Leibnitz, the other inventor of calculus. Although there is no doubt that Newton had the idea first, in the mid-1660s, there is also no doubt that Leibnitz (who lived from 1646 to 1716) hit on the idea independently a little later (Newton not having bothered to tell anyone of his work at the time) and that Leibnitz also came up with a more easily understood version. I don’t intend to go into the mathematical details; the key thing about calculus is that it makes it possible to calculate accurately, from a known starting situation, things that vary as time passes, such as the position of a planet in its orbit. It would be tedious to go into all the details of the Newton–Leibnitz dispute; what matters is that they did develop calculus in the second half of the seventeenth century, providing scientists of the eighteenth and subsequent centuries with the mathematical tools they needed to study processes in which change occurs. Modern physical science simply would not exist without calculus.

Newton’s great insights into these mathematical methods, and the beginnings of his investigation of gravity, occurred at a time when the routine of life in Cambridge was interrupted by the threat of plague. Not long after he graduated, the university was closed temporarily and its scholars dispersed to avoid the plague. In the summer of 1665, Newton returned to Lincolnshire, where he stayed until March 1666. It then seemed safe to return to Cambridge, but with the return of warm weather the plague broke out once more, and in June he left again for the country, staying in Lincolnshire until April 1667, when the plague had run its course. While in Lincolnshire, Newton divided his time between Woolsthorpe and Babington’s rectory in Boothby Pagnell, so there is no certainty about where the famous apple incident occurred (if indeed it really did occur at this time, as Newton claimed). But what is certain is that, in Newton’s own words, written half a century later, ‘in those days I was in the prime of my age for invention & minded Mathematicks & Philosophy more than at any time since’. At the end of 1666, in the midst of this inspired spell, Newton enjoyed his twenty-fourth birthday.

The way Newton later told the story, at some time during the plague years he saw an apple fall from a tree and wondered whether, if the influence of the Earth’s gravity could extend to the top of the tree, it might extend all the way to the Moon. He then calculated that the force required to hold the Moon in its orbit and the force required to make the apple fall from the tree could both be explained by the Earth’s gravity if the force fell off as one over the square of the distance from the centre of the Earth. The implication, carefully cultivated by Newton, is that he had the inverse square law by 1666, long before any discussions between Halley, Hooke and Wren. But Newton was a great one for rewriting history in his own favour, and the inverse square law emerged much more gradually than the story suggests. From the written evidence of Newton’s own papers that can be dated, there is nothing about the Moon in the work on gravity he carried out in the plague years. What started him thinking about gravity was the old argument used by opponents of the idea that the Earth could be spinning on its axis, to the effect that if it were spinning it would break up and fly apart because of centrifugal force. Newton calculated the strength of this outward force at the surface of the Earth and compared it with the measured strength of gravity, showing that gravity at the surface of the Earth is hundreds of times stronger than the outward force, so the argument doesn’t stand up. Then, in a document written some time after he returned to Cambridge (but certainly before 1670), he compared these forces to the ‘endeavour of the Moon to recede from the centre of the Earth’ and found that gravity at the surface of the Earth is about 4000 times stronger than the outward (centrifugal) force appropriate for the Moon moving in its orbit. This outward force would balance the force of the Earth’s gravity if gravity fell off in accordance with an inverse square law, but Newton did not explicitly state this at the time. He also noted, though, from Kepler’s laws, that the ‘endeavours of receding from the Sun’ of the planets in their orbits were inversely proportional to the squares of their distances from the Sun.

To have got this far by 1670 is still impressive, if not as impressive as the myth Newton later cultivated so assiduously. And remember that by this time, still not 30, he had essentially completed his work on light and on calculus. But the investigation of gravity now took a back seat as Newton turned to a new passion – alchemy. Over the next two decades, Newton devoted far more time and effort to alchemy than he had to all of the scientific work that we hold in such esteem today, but since this was a complete dead end there is no place for a detailed discussion of that work here.9 He also had other distractions revolving around his position at Trinity College and his own unorthodox religious convictions.

In 1667, Newton was elected to a minor Fellowship at Trinity, which would automatically become a major Fellowship when he became an MA in 1668. This gave him a further seven years to do whatever he liked, but involved making a commitment to orthodox religion – specifically, on taking up the Fellowship all new Fellows had to swear an oath that ‘I will either set Theology as the object of my studies and will take holy orders when the time prescribed by these statutes arrives, or I will resign from the college.’ The snag was that Newton was an Arian.10 Unlike Bruno, he was not prepared to go to the stake for his beliefs, but nor was he prepared to compromise them by swearing on oath that he believed in the Holy Trinity, which he would be required to do on taking holy orders. To be an Arian in England in the late seventeenth century was not really a burning offence, but if it came out it would exclude Newton from public office and certainly from a college named after the Trinity. Here was yet another reason for him to be secretive and introverted; and in the early 1670s, perhaps searching for a loophole, Newton developed another of his long-term obsessions, carrying out detailed studies of theology (rivalling his studies of alchemy and helping to explain why he did no new science after he was 30). He was not saved by these efforts, though, but by a curious stipulation in the terms laid down by Henry Lucas for his eponymous chair.

Newton had succeeded Barrow as Lucasian professor in 1669, when he was 26. The curious stipulation, which ran counter to all the traditions of the university, was that any holder of the chair was barred from accepting a position in the Church requiring residence outside Cambridge or ‘the cure of souls’. In 1675, using this stipulation as an excuse, Newton got permission from Isaac Barrow (by now Master of Trinity) to petition the King for a dispensation for all Lucasian professors from the requirement to take holy orders. Charles II, patron of the Royal Society (where, remember, Newton was by now famous for his reflecting telescope and work on light) and enthusiast for science, granted the dispensation in perpetuity, ‘to give all just encouragement to learned men who are & shall be elected to the said Professorship’. Newton was safe – on the King’s dispensation, he would not have to take holy orders, and the college would waive the rule which said that he had to leave after his initial seven years as a Fellow were up.

The wrangling of Hooke and Newton

In the middle of all the anxiety about his future in Cambridge, Newton was also embroiled in the dispute with Hooke about priority over the theory of light, culminating in the ‘shoulders of Giants’ letter in 1675. We can now see why Newton regarded this whole business with such irritation – he was far more worried about his future position in Cambridge than about being polite to Hooke. Ironically, though, while Newton was distracted from following up his ideas about gravity, in 1674 Hooke had struck to the heart of the problem of orbital motion. In a treatise published that year, he discarded the idea of a balance of forces, some pushing inwards and some pushing outwards, to hold an object like the Moon in its orbit. He realized that the orbital motion results from the tendency of the Moon to move in a straight line, plus a single force pulling it towards the Earth. Newton, Huygens and everyone else still talked about a ‘tendency to recede from the centre’, or some such phrase, and the implication, even in Newton’s work so far, was that something like Descartes’s swirling vortices were responsible for pushing things back into their orbits in spite of this tendency to move outwards. Hooke also did away with the vortices, introducing the idea of what we would now call ‘action at a distance’ – gravity reaching out across empty space to tug on the Moon or the planets.

In 1679, after the dust from their initial confrontation had settled, Hooke wrote to Newton asking for his opinion on these ideas (which had already been published). It was Hooke who introduced Newton to the idea of action at a distance (which immediately appears, without comment, in all of Newton’s subsequent work on gravity) and to the idea that an orbit is a straight line bent by gravity. But Newton was reluctant to get involved, and wrote to Hooke that:

I had for some years past been endeavouring to bend my self from Philosophy to other studies in so much yt I have long grutched the time spent in yt study…I hope it will not be interpreted out of any unkindness to you or ye R. Society that I am backward in engaging myself in these matters.

In spite of this, Newton did suggest a way to test the rotation of the Earth. In the past, it had been proposed that the rotation of the Earth ought to show up if an object was dropped from a sufficiently tall tower, because the object would be left behind by the rotation and fall behind the tower. Newton pointed out that the top of the tower had to be moving faster than its base, because it was further from the centre of the Earth and had correspondingly more circumference to get round in 24 hours. So the dropped object ought to land in front of the tower. Rather carelessly, in a drawing to show what he meant, Newton carried through the trajectory of the falling body as if the Earth were not there, spiralling into the centre of the Earth under the influence of gravity. But he concluded the letter by saying:

But yet my affection to Philosophy being worn out, so that I am almost as little concerned about it as one tradesman uses to be about another man’s trade or a country man about learning, I must acknowledge my self avers from spending that time in writing about it Wch I think I can spend otherwise more to my own content.

But drawing that spiral drew Newton into more correspondence on ‘Philosophy’ whether he liked it or not. Hooke pointed out the error and suggested that the correct orbit followed by the falling object, assuming it could pass through the solid Earth without resistance, would be a kind of shrinking ellipse. Newton in turn corrected Hooke’s surmise by showing that the object orbiting inside the Earth would not gradually descend to the centre along any kind of path, but would orbit indefinitely, following a path like an ellipse, but with the whole orbit shifting around as time passed. Hooke in turn replied to the effect that Newton’s calculation was based on a force of attraction with ‘an aequall power at all Distances from the center…But my supposition is that the Attraction always is in a duplicate proportion to the Distance from the Center Reciprocall’, in other words, an inverse square law.

Newton never bothered to reply to this letter, but the evidence is that, in spite of his affection to philosophy being worn out, this was the trigger that stimulated him, in 1680, to prove (where Hooke and others could only surmise) that an inverse square law of gravity requires the planets to be in elliptical or circular orbits, and implied that comets should follow either elliptical or parabolic paths around the Sun.11 And that is why he was ready with the answer when Halley turned up on his doorstep in 1684.

Newton’s Principia Mathematica: the inverse square law and the three laws of motion

It wasn’t all plain sailing after that, but Halley’s cajoling and encouragement following that encounter in Cambridge led first to the publication of a nine-page paper (in November 1684) spelling out the inverse square law work, and then to the publication in 1687 of Newton’s epic three-volume work Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, in which he laid the foundations for the whole of physics, not only spelling out the implications of his inverse square law of gravity and the three laws of motion, which describe the behaviour of everything in the Universe, but making it clear that the laws of physics are indeed universal laws that affect everything. There was still time for one more glimpse of Newton’s personality to surface – when Hooke complained that the manuscript (which he saw in his capacity at the Royal) gave him insufficient credit (a justifiable complaint, since he had achieved and passed on important insights even if he didn’t have the skill to carry through the mathematical work as Newton could), Newton at first threatened to withdraw the third volume from publication and then went through the text before it was sent to the printers, savagely removing any reference at all to Hooke.

Apart from the mathematical brilliance of the way he fitted everything together, the reason why the Principia made such a big impact is because it achieved what scientists had been groping towards (without necessarily realizing it) ever since Copernicus – the realization that the world works on essentially mechanical principles that can be understood by human beings, and is not run in accordance with magic or the whims of capricious gods.