Humphry Davy’s work on gases; electrochemical research – John Dalton’s atomic model; first talk of atomic weights – Jöns Berzelius and the study of elements – Avogadro’s number – William Prout’s hypothesis on atomic weights – Friedrich Wöhler: studies in organic and inorganic substances – Valency – Stanislao Cannizzaro: the distinction between atoms and molecules – The development of the periodic table, by Mendeleyev and others – The science of thermodynamics – James Joule on thermodynamics – William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) and the laws of thermodynamics – James Clerk Maxwell and Ludwig Boltzmann: kinetic theory and the mean free path of molecules – Albert Einstein: Avogadro’s number, Brownian motion and why the sky is blue

Although the figure of Charles Darwin dominates any discussion of nineteenth-century science, he is something of an anomaly. It is during the nineteenth century – almost exactly during Darwin’s lifetime – that science makes the shift from being a gentlemanly hobby, where the interests and abilities of a single individual can have a profound impact, to a well-populated profession, where progress depends on the work of many individuals who are, to some extent, interchangeable. Even in the case of the theory of natural selection, as we have seen, if Darwin hadn’t come up with the idea, Wallace would have, and from now on we will increasingly find that discoveries are made more or less simultaneously by different people working independently and largely in ignorance of one another. The other side of this particular coin, unfortunately, is that the growing number of scientists brings with it a growing inertia and resulting resistance to change, which means that all too often when some brilliant individual does come up with a profound new insight into the way the world works, this is not accepted immediately on merit and may take a generation to work its way into the collective received wisdom of science.

We shall shortly see this inertia at work in the reaction (or lack of reaction) to the ideas of John Dalton about atoms; we can also conveniently see the way science grew in terms of Dalton’s life. When Dalton was born, in 1766, there were probably no more than 300 people who we would now class as scientists in the entire world. By 1800, when Dalton was about to carry out the work for which he is now remembered, there were about a thousand. By the time he died, in 1844, there were about 10,000, and by 1900 somewhere around 100,000. Roughly speaking, the number of scientists doubled every fifteen years during the nineteenth century. But remember that the whole population of Europe doubled, from about 100 million to about 200 million, between 1750 and 1850, and the population of Britain alone doubled between 1800 and 1850, from roughly 9 million to roughly 18 million. The number of scientists did increase as a proportion of the population, but not as dramatically as the figures for scientists alone suggest at first sight.1

30. Dalton’s symbols for the chemical elements.

Humphry Davy’s work on gases; electrochemical research

The transition from amateurism to professionalism is nicely illustrated by the career of Humphry Davy, who was actually younger than Dalton, although he had a shorter life. Davy was born in Penzance, Cornwall, on 17 December 1778. Cornwall was then still almost a separate country from England, and the Cornish language had not entirely died out; but from an early age Davy had ambitions that extended beyond the confines of his native county. Davy’s father, Robert, owned a small farm and also worked as a woodcarver, but was never financially successful. His mother, Grace, later ran a milliner’s shop with a French woman who had fled the Revolution, but in spite of her contribution the financial circumstances of the family were so difficult that at the age of 9, Humphry (the eldest of five children) went to live with his mother’s adoptive father, John Tonkin, a surgeon. When Humphry’s father died in 1794, leaving his family nothing but debts, it was Tonkin who advised Davy, who had been educated at Truro Grammar School without showing any conspicuous intellectual ability, to become the apprentice of a local apothecary, with the ultimate ambition of going to Edinburgh to study medicine. Around this time, Davy also learned French, from a refugee French priest, a skill that was soon to prove invaluable to him.

Davy seems to have been a promising apprentice and embarked on a programme of self-education reminiscent of Benjamin Thompson at a similar age. He might well have become a successful apothecary, or even a doctor. But the winter of 1797/8 marked a turning point in the young man’s life. At the end of 1797, shortly before his nineteenth birthday, he read Lavoisier’s Traité Elémentaire in the original French and became fascinated by chemistry. A few weeks earlier, Davy’s widowed mother, still struggling to make ends meet, had taken in a lodger for the winter, a young man who suffered from consumption (TB) and had been sent to the relatively mild climate of Cornwall for the winter for his health. He happened to be Gregory Watt, the son of James Watt, and had studied chemistry at Glasgow University. Gregory Watt and Humphry Davy formed a friendship which lasted until Watt’s death, in 1805, at the age of 27. Watt’s presence in Penzance that winter gave Davy someone to share his developing interest in chemistry with; in 1798, through carrying out his own experiments, he developed his ideas about heat and light (still very much in the province of chemistry in those days) in a lengthy manuscript. Many of these ideas were naive and do not stand up to close scrutiny today (although it is noteworthy that Davy discarded the idea of caloric), but this was still an impressive achievement for a self-taught provincial 19-year-old. It was through Gregory Watt and his father James that Humphry Davy was initially introduced (by correspondence) to Dr Thomas Beddoes, of Bristol, and sent him his paper on heat and light.

Beddoes (1760–1808) had studied under Joseph Black in Edinburgh, before moving on to London and then Oxford, where he completed his medical studies and taught chemistry from 1789 to 1792. He then became intrigued by the discovery of different gases and decided to set up a clinic to investigate the potential of these gases in medicine. He had the (rather alarming to modern eyes) notion that breathing hydrogen might cure consumption, and moved to Bristol, where he practised medicine while obtaining funds for what became, in 1798, the Pneumatic Institute. Beddoes needed an assistant to help him with the chemical work and young Davy got the job. He left Penzance on 2 October 1798, still a couple of months short of his twentieth birthday.

It was in Bristol that Davy carried out the experiments with the gas now known as nitrous oxide, which made his name known more widely. Seeing no other way to find out how it affected the human body, he prepared ‘four quarts’ of nitrous oxide and breathed it from a silk bag, having first emptied his lungs as far as possible. He immediately discovered the intoxicating properties of the gas, which soon gave it the name ‘laughing gas’ as it became a sensation among the pleasure-seeking classes. A little later, while suffering considerable discomfort from a wisdom tooth, Davy also discovered, by accident, that the gas dulled the sensation of pain, and even wrote, in 1799, that ‘it may probably be used with advantage during surgical operations’. At the time, unfortunately, this suggestion was not followed up, and it was left to the American dentist Horace Wells to pioneer the use of ‘laughing gas’ when extracting teeth, in 1844.

Davy continued to experiment on himself by inhaling various gases, with near-fatal results on one occasion. He was experimenting with the substance known as water gas (actually a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen), produced by passing steam over hot charcoal. Carbon monoxide is extremely poisonous, rapidly but painlessly inducing a deep sleep which leads to death (which is why many suicides choose to kill themselves by breathing the exhaust fumes from a car engine). Davy just had time to drop the mouthpiece of the breathing bag he was using from his lips before collapsing, suffering nothing worse than a splitting headache when he awoke. But it was nitrous oxide that made his name.

After carrying out an intensive study of the chemical and physiological properties of the gas for about ten months, Davy wrote up his discoveries in a book more than 80,000 words long, completed in less than three months and published in 1800. The timing could not have been better for his career. In 1800, as the work on nitrous oxide drew to a close, Davy was becoming interested in electricity, as a result of the news of Volta’s invention (or discovery) of the galvanic pile; starting out with the classic experiment in which water is decomposed into hydrogen and oxygen by the action of an electric current, Davy soon convinced himself there was a significant relationship between chemistry and electricity. While he was starting out on these studies, Count Rumford (as Benjamin Thompson now was) was trying to establish the Royal Institution (RI) in London. The RI had been founded in March 1799, but the first professor of chemistry appointed to the RI, Thomas Garnett, was not proving a success. His first lectures had gone down well, but a second series suffered from a lack of preparation and an unenthusiastic presentation. There were reasons for this – Garnett’s wife had recently died and he seems to have lost his enthusiasm for everything, dying himself in 1802 at the age of only 36. Whatever the reasons for Garnett’s failure, Rumford had to move quickly if the RI was to build on its promising beginning, and he invited Davy, the brightest rising star in the firmament of British chemistry, to come on board as assistant lecturer in chemistry and director of the laboratory at the RI, at an initial salary of 100 guineas per annum plus accommodation at the RI, with the possibility of succeeding Garnett in the top job. Davy accepted, and took up the post on 16 February 1801. He was a brilliant success as a lecturer, both in terms of the drama and excitement of his always thoroughly prepared and rehearsed talks, and in terms of his good looks and charisma, which had fashionable young ladies flocking to the lectures regardless of their content. Garnett (under pressure from Rumford) soon resigned, and Davy became top dog at the RI, appointed professor of chemistry in May 1802, shortly before Rumford left London and settled in Paris. Davy was still only 23 years old and had received no formal education beyond what Truro Grammar School could offer. In that sense, he was one of the last of the great amateur scientists (although not, strictly speaking, a gentleman); but as a salaried employee of the RI, he was also one of the first professional scientists.

Although usually remembered as a ‘pure’ scientist, Davy’s greatest contemporary achievements were in promoting science, both in a general way at the RI and in terms of industrial and (in particular) agricultural applications. For example, he gave a famous series of lectures, by arrangement with the Board of Agriculture, on the relevance of chemistry to agriculture. It is a measure both of the importance of the subject and Davy’s presentational skills that he was later (in 1810) asked to repeat the lectures (plus a series on electrochemistry) in Dublin, for a fee of 500 guineas; a year later he gave another series of lectures there for a fee of 750 guineas – more than seven times his starting salary at the RI in 1801. He was also awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws by Trinity College, Dublin; this was the only degree he ever received.

We can gain an insight into Davy’s method of preparing lectures from an account recorded by John Dalton when he gave a series of lectures at the RI in December 1803 (the year Davy became a Fellow of the Royal Society). Dalton tells us2 how he wrote out his first lecture entirely, and how Davy took him into the lecture hall the evening before he was to talk and made him read it all out while Davy sat in the furthest corner and listened; then Davy read the lecture while Dalton listened. ‘Next day I read it to an audience of about 150 to 200 people…they gave me a very generous plaudit at the conclusion.’ But Davy, like so many of his contemporaries (as we shall see), was reluctant to accept the full implications of Dalton’s atomic model.

Davy’s electrochemical research led him to produce a masterly analysis and overview of the young science in the Royal Society’s Bakerian Lecture in 1806 – so masterly and impressive, indeed, that he was awarded a medal and prize by the French Academy the following year, even though Britain and France were still at war. Shortly afterwards, using electrical currents passed through potash and soda, he isolated two previously unknown metals and named them potassium and sodium. In 1810, Davy isolated and named chlorine. Accurately defining an element as a substance that cannot be decomposed by any chemical process, he showed that chlorine is an element and established that the key component of all acids is hydrogen, not oxygen. This was the high point of Davy’s career as a scientist, and in many ways he never fulfilled his real potential, partly because his lack of formal training led him into sometimes slapdash work lacking proper quantitative analysis, and partly because his head was turned by fame and fortune, so that he began to enjoy the social opportunities provided by his position more than his scientific work. He was knighted in 1812, three days before marrying a wealthy widow and a few months before appointing Michael Faraday (his eventual successor) as an assistant at the RI. The same year, he resigned his post as professor of chemistry at the RI, being succeeded by William Brande (1788–1866), but kept his role as director of the laboratory. An extensive tour of Europe with his bride (and Faraday) soon followed, thanks to a special passport provided by the French to the famous scientist (the war, of course, continued until 1815). It was after the party returned to England that Davy designed the famous miners’ safety lamp which bears his name, although the work that led to this design was so meticulous and painstaking (and therefore so unlike Davy’s usual approach) that some commentators suggest that Faraday must have had a great deal to do with it. In 1818, Davy became a baronet, and in 1820 he was elected President of the Royal Society, where he took great delight in all the ceremonial attached to the post and became such a snob that in 1824 he was the only Fellow to oppose the election of Faraday to the Royal. From 1825 onwards, however, Davy became chronically ill; he retired as director of the laboratory at the RI and played no further part in the affairs of British science. From 1827 onwards, he travelled in France and Italy, where the climate was more beneficial to his health, and died, probably of a heart attack, in Geneva on 29 May 1829, in his fifty-first year.

If Humphry Davy was one of the first people to benefit from the slow professionalization of science, the scientific career (such as it was) of John Dalton shows just how far this process still had to go in the first decades of the nineteenth century. Dalton was born in the village of Eaglesfield, in Cumberland, probably in the first week of September and definitely in 1766. He came from a Quaker family, but for some reason his exact birth date was not recorded in the Quaker register. We know that he had three siblings who died young and two, Jonathan and Mary, who survived; Jonathan was the eldest, but it is not recorded whether Mary was older or younger than John. Their father was a weaver, and the family occupied a two-roomed cottage, one room for working and the rest of the daily routine, the other for sleeping. Dalton attended a Quaker school where, instead of being force-fed with Latin, he was allowed to develop his interest in mathematics, and he came to the attention of a wealthy local Quaker, Elihu Robinson, who gave him access to his books and periodicals. At the age of 12, Dalton had to begin making a contribution to the family income and at first he tried teaching even younger children (some of them physically bigger than him) from his home and then from the Quaker Meeting House, for a modest fee; but this was not a success and he turned instead to farm work. In 1781, however, he was rescued from a life on the land when he went to join his brother Jonathan, who was helping one of their cousins, George Bewley, to run a school for Quakers in Kendal, a prosperous town with a large Quaker population. The two brothers took over the school when their cousin retired in 1785, with their sister keeping house for them, and John Dalton stayed there until 1793. He gradually developed his scientific interests, both answering and setting questions in popular magazines of the day, and beginning a long series of meteorological observations, which he recorded daily from 24 March 1787 until he died.

Frustrated by the limited opportunities and poor financial rewards offered by his dead-end job, Dalton developed an ambition to become either a lawyer or a doctor, and worked out how much it would cost to study medicine in Edinburgh (as a Quaker, of course, he could not then have attended either Oxford or Cambridge regardless of the cost). He was certainly up to the task intellectually; but friends advised him that there was no hope of obtaining the funds to fulfil such an ambition. Partly to bring in a little extra money, partly to satisfy his scientific leanings, Dalton began to give public lectures for which a small fee was charged, gradually extending his geographical range to include Manchester. Partly as a result of the reputation he gained through this work, in 1793 he became a teacher of mathematics and natural philosophy at a new college in Manchester, founded in 1786 and prosaically named New College. A book of his meteorological observations, written in Kendal, was published shortly after he moved to Manchester. In an appendix to that book, Dalton discusses the nature of water vapour and its relationship to air, describing the vapour in terms of particles which exist between the particles of air, so that the ‘equal and opposite pressures’ of the surrounding air particles on a particle of vapour ‘cannot bring it nearer to another particle of vapour, without which no condensation can take place’. With hindsight, this can be seen as the precursor to his atomic theory.3

Manchester was a boom town in the 50 years Dalton lived there, with the cotton industry moving out of the cottages and into factories in the cities. Although he was not directly involved in industry, Dalton was part of this boom, because the very reason for the existence of educational establishments such as New College was to cater for the need of a growing population to develop the technical skills required by the new way of life. Dalton taught there until 1799; by then, he was well enough known to make a decent living as a private tutor, and he stayed in Manchester for the rest of his life. One reason why Dalton became well known, almost as soon as he arrived in Manchester, was that he was colour blind. This condition had not previously been recognized, but Dalton came to realize that he could not see colours the same way most other people could, and found that his brother was affected in the same way. Blue and pink, in particular, were indistinguishable to both of them. On 31 October 1794 Dalton read a paper to the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society describing his detailed analysis of the condition, which soon became known as Daltonism (a name still used in some parts of the world).

Over the next ten years or so, Dalton’s keen interest in meteorology led him to think deeply about the nature of a mixture of gases, building from the ideas about water vapour just quoted. He never developed the idea of a gas as made up of huge numbers of particles in constant motion, colliding with one another and with the walls of their container, but thought instead in static terms, as if a gas were made of particles separated from one another by springs. But even with this handicap, he was led to consider the relationship between the volumes occupied by different gases under various conditions of temperature and pressure, the way gases dissolved in water and the influence of the weights of the individual particles in the gas on its overall properties. By 1801, he had come up with the law of partial pressures, which says that the total pressure exerted by a mixture of gases in a container is the sum of the pressures each gas would exert on its own under the same conditions (in the same container at the same temperature).

John Dalton’s atomic model: first talk of atomic weights

It isn’t possible to reconstruct Dalton’s exact train of thought, since his notes are incomplete, but in the early 1800s he became convinced that each element was made up of a different kind of atom, unique to that element, and that the key distinguishing feature which made one element different from another was the weight of its atoms, with all the atoms of a particular element having the same weight, being indistinguishable from one another. Elementary atoms themselves, could be neither created nor destroyed. These elementary atoms could, however, combine with one another to form ‘compound atoms’ (what we would now call molecules) in accordance with specific rules. And Dalton even came up with a system of symbols to represent the different elements, although this idea was never widely accepted and soon became superceded by the now familiar alphabetical notation based on the names of the elements (in some cases, on their Latin names). Perhaps the biggest flaw in Dalton’s model is that he did not realize that elements such as hydrogen are composed of molecules (as we would now call them), not individual atoms – H2 not H. Partly for this reason, he got some molecular combinations wrong, and in modern notation he would have thought of water as HO, not H2O.

Although parts of Dalton’s model were described in various papers and lectures, the first full account of the idea was presented in the lectures at the RI in December 1803 and January 1804, where Davy helped Dalton to hone his presentation. The system was described (without being singled out as having any particular merit) by Thomas Thomson in the third edition of his book System of Chemistry in 1807, and Dalton’s own book, A New System of Chemical Philosophy, which included a list of estimated atomic weights, appeared in 1808 (the very first table of atomic weights had been presented at the end of a paper by Dalton in 1803).

In spite of the seeming modernity and power of Dalton’s model, though, it did not take the scientific world by storm at the end of the first decade of the nineteenth century. Many people found it hard, sometimes on philosophical grounds, to accept the idea of atoms (with the implication that there was nothing at all in the spaces between atoms) and even many of those who used the idea regarded it as no more than a heuristic device, a tool to use in working out how elements behave as if they were composed of tiny particles, without it necessarily being the case that they are composed of tiny particles. It took almost half a century for the Daltonian atom to become really fixed as a feature of chemistry, and it was only in the early years of the twentieth century (almost exactly a hundred years after Dalton’s insight) that definitive proof of the existence of atoms was established. Dalton himself made no further contribution to the development of these ideas, but was heaped with honours during his long life (including becoming a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1822 and succeeding Davy as one of only eight Foreign Associates of the French Academy in 1830). When he died, in Manchester on 27 July 1844, he was given a completely over-the-top funeral, totally out of keeping with his Quaker lifestyle, involving a procession of a hundred carriages – but by then, the atomic theory was well on the way to becoming received wisdom.

Jöns Berzelius and the study of elements

The next key step in developing Dalton’s idea had been made by the Swedish chemist Jöns Berzelius, who was born in Väversunda on 20 August 1779. His father, a teacher, died when Berzelius was 4, and his mother then married a pastor, Anders Ekmarck. Berzelius went to live with the family of an uncle when his mother also died, in 1788, and in 1796 began to study medicine at the University of Uppsala, interrupting his studies in order to work to pay his fees, but graduating with an MD in 1802. After he graduated, Berzelius moved to Stockholm, where he worked at first as an unpaid assistant to the chemist Wilhelm Hisinger (1766–1852) and then in a similar capacity as assistant to the professor of medicine and pharmacy at the College of Medicine in Stockholm; he did this so well that when the professor died in 1807, Berzelius was appointed to replace him. He soon gave up medicine and concentrated on chemistry.

His early work had been in electrochemistry, inspired, like Davy, by the work of Volta, but thanks to his formal training Berzelius was a much more meticulous experimenter than Davy. He was one of the first people to formulate the idea (true up to a point, but not universally so) that compounds are composed of electrically positive and electrically negative parts, and he was an early enthusiast for Dalton’s atomic theory. From 1810 onwards, Berzelius carried out a series of experiments to measure the proportions in which different elements combine with one another (studying 2000 different compounds by 1816), which went a long way towards providing the experimental underpinning that Dalton’s theory required and enabled Berzelius to produce a reasonably accurate table of the atomic weights of all forty elements known at the time (measured relative to oxygen, rather than to hydrogen). He was also the inventor of the modern alphabetical system of nomenclature for the elements, although it took a long time for this to come into widespread use. Along the way, Berzelius and his colleagues in Stockholm isolated and identified several ‘new’ elements, including selenium, thorium, lithium and vanadium.

It was around this time that chemists were beginning to appreciate that elements could be grouped in ‘families’ with similar chemical properties, and Berzelius gave the name ‘halogens’ (meaning salt-formers) to the group which includes chlorine, bromine and iodine; a dab hand at inventing names, he also coined the terms ‘organic chemistry’, ‘catalysis’ and ‘protein’. His Textbook of Chemistry, first published in 1803, went through many editions and was highly influential. It’s a measure of his importance to chemistry and the esteem in which he was held in Sweden that on his wedding day, in 1835, he was made a baron by the King of Sweden. He died in Stockholm in 1848.

Avogadro’s number

But neither Berzelius nor Dalton (nor hardly anyone else, for that matter) immediately picked up on the two ideas which together carried the idea of atoms forward, and which were both formulated by 1811. First, the French chemist Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (1778–1850) realized in 1808, and published in 1809, that gases combine in simple proportions by volume, and that the volume of the products of the reaction (if they are also gaseous) is related in a simple way to the volumes of the reacting gases. For example, two volumes of hydrogen combine with one volume of oxygen to produce two volumes of water vapour. This discovery, together with experiments which showed that all gases obey the same laws of expansion and compression, led the Italian Amadeo Avogadro (1776–1856) to announce, in 1811, his hypothesis that at a given temperature, the same volume of any gas contains the same number of particles. He actually used the word ‘molecules’, but where Dalton used ‘atom’ to mean both what we mean by atoms and what we mean by molecules, Avogadro used ‘molecule’ to mean both what we mean by molecules and what we mean by atoms. For simplicity, I shall stick to the modern terminology. Avogadro’s hypothesis explained Gay-Lussac’s discovery if, for example, each molecule of oxygen contains two atoms of the element, which can be divided to share among the molecules of hydrogen. This realization that oxygen (and other elements) could exist in polyatomic molecular form (in this case, O2 rather than O) was a crucial step forward. So two volumes of hydrogen contain twice as many molecules as one volume of oxygen, and when they combine, each oxygen molecule provides one atom to each pair of hydrogen molecules, making the same number of molecules as there were in the original volume of hydrogen.

Using modern notation, 2H2 + O2 → 2H2O.

Avogadro’s ideas fell on stony ground at the time, and progress in developing the atomic hypothesis barely moved forward for decades, handicapped by the lack of experiments which could test the hypothesis. Ironically, the experiments were just good enough to cast considerable doubt on another good idea which emerged around this time. In 1815, the British chemist William Prout (1785–1850), building from Dalton’s work, suggested that the atomic weights of all elements are exact multiples of the atomic weight of hydrogen, implying that in some way heavier elements might be built up from hydrogen. But the experimental techniques of the first half of the nineteenth century were good enough to show that this relationship did not hold exactly, and many atomic weights determined by chemical techniques could not be expressed as perfect integer multiples of the atomic weight of hydrogen. It was only in the twentieth century, with the discovery of isotopes (atoms of the same element with slightly different atomic weights, but each isotope having an atomic weight a precise multiple of the weight of one hydrogen atom) that the puzzle was resolved (since chemically determined atomic weights are an average of the atomic weights of all the isotopes of an element present) and Prout’s hypothesis was seen as a key insight into the nature of atoms.

William Prout’s hypothesis on atomic weights

But while the subtleties of chemistry at the atomic level failed to yield much to investigation for half a century, a profound development was taking place in the understanding of what happens at a higher level of chemical organization. Experimenters had long been aware that everything in the material world falls into one of two varieties of chemical substances. Some, like water or common salt, can be heated and seem superficially to change their character (glowing red hot, melting, evaporating or whatever), but when cooled, revert back to the same chemical state they started from. Others, such as sugar or wood, are completely altered by the action of heat, so that it is very difficult, for example, to ‘unburn’ a piece if wood. It was in 1807 that Berzelius formalized the distinction between the two kinds of material. Since the first group of materials is associated with non-living systems, while the second group is closely related to living systems, he gave them the names ‘inorganic’ and ‘organic’. As chemistry developed, it became clear that organic materials are, by and large, made up of much more complex compounds than inorganic materials; but it was also thought that the nature of organic substances was related to the presence of a ‘life force’ which made chemistry operate differently in living things than in non-living things.

Friedrich Wöhler: studies in organic and inorganic substances

The implication was that organic substances could only be made by living systems, and it came as a dramatic surprise when in 1828 the German chemist Friedrich Wöhler (1800–1882) accidentally discovered, during the course of experiments with a quite different objective, that urea (one of the constituents of urine) could be made by heating the simple substance ammonium cyanate. Ammonium cyanate was then regarded as an inorganic substance, but in the light of this and similar experiments which manufactured organic materials from substances which had never been associated with life, the definition of ‘organic’ changed. By the end of the nineteenth century it was clear that there was no mysterious life force at work in organic chemistry, and that there are two things which distinguish organic compounds from inorganic compounds. First, organic compounds are often complex, in the sense that each molecule contains many atoms of (usually) different elements. Second, organic compounds all contain carbon (which is, in fact, the reason for their complexity, because, as we shall see, carbon atoms are able to combine in many interesting ways with lots of other atoms and with other carbon atoms). This means that ammonium cyanate, which does contain carbon, is now regarded as an organic substance – but this doesn’t in any way diminish the significance of Wöhler’s discovery. It is now even possible to manufacture complete strands of DNA in the laboratory from simple inorganic materials.

The usual definition of an organic molecule today is any molecule that contains carbon, and organic chemistry is the chemistry of carbon and its compounds. Life is seen as a product of carbon chemistry, obeying the same chemical rules that operate throughout the world of atoms and molecules. Together with Darwin’s and Wallace’s ideas about evolution, this produced a major nineteenth-century shift in the view of the place of humankind in the Universe – natural selection tells us that we are part of the animal kingdom, with no evidence of a uniquely human ‘soul’; chemistry tells us that animals and plants are part of the physical world, with no evidence of a special ‘life force’.

Valency

By the time all this was becoming clear, however, chemistry had at last got to grips with atoms. Among the key concepts that emerged out of the decades of confusion, in 1852 the English chemist Edward Frankland (1825–1899) gave the first reasonably clear analysis of what became known as valency, a measure of the ability of one element to combine with another – or, as soon became clear, the ability of atoms of a particular element to combine with other atoms. Among many terms used in the early days to describe this property, one, ‘equivalence’, led through ‘equivalency’ to the expression used today. In terms of chemical combinations, in some sense two amounts of hydrogen are equivalent to one of oxygen, one of nitrogen to three of hydrogen, and so on. In 1858, the Scot Archibald Couper (1831–1892) wrote a paper in which he introduced the idea of bonds into chemistry, simplifying the representation of valency and the way atoms combine. Hydrogen is now said to have a valency of 1, meaning that it can form one bond with another atom. Oxygen has a valency of 2, meaning that it can form two bonds. So, logically enough, each of the two bonds ‘belonging to’ one oxygen atom can link up with one hydrogen atom, forming water – H2O, or, if you prefer, H–O–H, where the dashes represent bonds. Similarly, nitrogen has a valency of three, making three bonds, so it can combine with three hydrogen atoms at a time, producing ammonia, NH3. But the bonds can also form between two atoms of the same element, as in oxygen O2, which can be represented as O=O. Best of all, carbon has a valency of four, so it can form four separate bonds with four separate atoms, including other atoms of carbon, at the same time.4 This property lies at the heart of carbon chemistry, and Couper was quick to suggest that the complex carbon compounds which form the basis of organic chemistry might consist of a chain of carbon atoms ‘holding hands’ in this way with other atoms attached to the ‘spare’ bonds at the sides of the chain. The publication of Couper’s paper was delayed, and the same idea was published first, independently, by the German chemist Friedrich August Kekulé (1829–1896); this overshadowed Couper’s work at the time. Seven years later, Kekulé had the inspired insight that carbon atoms could also link up in rings (most commonly in a ring of six carbon atoms forming a hexagon) with bonds sticking out from the ring to link up with other atoms (or even with other rings of atoms).

Stanislao Cannizzaro: the distinction between atoms and molecules

With ideas like those of Couper and Kekulé in the air at the end of the 1850s, the time was ripe for somebody to rediscover Avogadro’s work and put it in its proper context. That somebody was Stanislao Cannizzaro, and although what he actually did can be described fairly simply, he had such an interesting life that it is impossible to resist the temptation to digress briefly to pick out some of the highlights from it. Cannizzaro, the son of a magistrate, was born in Palermo, Sicily, on 13 July 1826. He studied at Palermo, Naples, Pisa and Turin, before working as a laboratory assistant in Pisa from 1845 to 1847. He then returned to Sicily to fight in the unsuccessful rebellion against the ruling Bourbon regime of the King of Naples, part of the wave of uprisings which has led historians to dub 1848 ‘the year of revolutions’ in Europe (Cannizzaro’s father was at this time Chief of Police, which must have made life doubly interesting). With the failure of the uprising, Cannizzaro, sentenced to death in his absence, went into exile in Paris, where he worked with Michel Chevreul (1786–1889), professor of chemistry at the Natural History Museum. In 1851, Cannizzaro was able to return to Italy, where he taught chemistry at the Collegio Nazionale at Alessandria, in Piedmont,5 before moving on to Genoa in 1855 as professor of chemistry. It was while in Genoa that he came across Avogadro’s hypothesis and set it in the context of the progress made in chemistry since 1811. In 1858, just two years after Avogadro had died, Cannizzaro produced a pamphlet (what would now be called a preprint) in which he drew the essential distinction between atoms and molecules (clearing up the confusion which had existed since the time of the seminal work by Dalton and Avogadro), and explained how the observed behaviour of gases (the rules of combination of volumes, measurements of vapour density and so on) together with Avogadro’s hypothesis could be used to calculate atomic and molecular weights, relative to the weight of one atom of hydrogen; and he drew up a table of atomic and molecular weights himself. The pamphlet was widely circulated at an international conference held in Karlsruhe, Germany, in 1860, and was a key influence on the development of the ideas which led to an understanding of the periodic table of the elements.

Cannizzaro himself, however, was distracted from following up these ideas. Later in 1860, he joined Giuseppe Garibaldi’s forces in the invasion of Sicily which not only ejected the Neapolitan regime from the island but quickly led to the unification of Italy under Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia. In 1861, after the fighting, Cannizzaro became professor of chemistry in Palermo, where he stayed until 1871 before moving to Rome, where as well as being professor of chemistry at the university he founded the Italian Institute of Chemistry, became a senator in the Parliament and later Vice President of the Senate. He died in Rome on 10 May 1910, having lived to see the reality of atoms established beyond reasonable doubt.

The development of the periodic table, by Mendeleyev and others

The story of the discovery (or invention) of the periodic table is a curious mixture, highlighting the way in which, when the time is ripe, the same scientific discovery is likely to be made by several people independently, but also demonstrating the common reluctance of the old guard to accept new ideas. Hot on the heels of Cannizzaro’s work, in the early 1860s both the English industrial chemist John Newlands (1837–1898) and the French mineralogist Alexandre Béguyer de Chancourtois (1820–1886) independently realized that if the elements are arranged in order of their atomic weight, there is a repeating pattern in which elements at regular intervals, with atomic weights separated by amounts that are multiples of eight times the atomic weight of hydrogen, have similar properties to one another.6 Béguyer’s work, published in 1862, was simply ignored (which may have been partly his own fault, for failing to explain his idea clearly and not even providing an explanatory diagram to illustrate it), but when Newlands, who knew nothing of Béguyer’s work, published a series of papers touching on the subject in 1864 and 1865, he suffered the even worse fate of being savagely ridiculed by his peers, who said that the idea of arranging the chemical elements in order of their atomic weight was no more sensible than arranging them in alphabetical order of their names. The key paper setting out his idea in full was rejected by the Chemical Society and only published in 1884, long after Dmitri Mendeleyev had been hailed as the discoverer of the periodic table. In 1887, the Royal Society awarded Newlands their Davy Medal, although they never got around to electing him as a Fellow.

But Mendeleyev wasn’t even the third person to come up with the idea of the periodic table. That honour, such as it is, belongs to the German chemist and physician Lothar Meyer (1830–1895), although, as he himself later acknowledged, to some extent he lacked the courage of his convictions, which is why the prize eventually went to Mendeleyev. Meyer made his name in chemistry through writing a textbook, The Modern Theory of Chemistry, which was published in 1864. He was an enthusiastic follower of Cannizzaro’s ideas, which he expounded in the book. While he was preparing the book, he noticed the relationship between the properties of a chemical element and its atomic weight, but was reluctant to promote this novel and as yet untested idea in a textbook, so he only hinted at it. Over the next few years, Meyer developed a more complete version of the periodic table, intended to be included in a second edition of his book, which was ready in 1868, but did not get into print until 1870. By that time, Mendeleyev had propounded his version of the periodic table (in ignorance of all the work along similar lines that had been going on in the 1860s), and Meyer always acknowledged Mendeleyev’s priority, not least because Mendeleyev had the courage (or chutzpah) to take a step that Meyer never took, predicting the need for ‘new’ elements to plug gaps in the periodic table. But Meyer’s independent work was widely recognized, and Meyer and Mendeleyev shared the Davy medal in 1882.

It’s a little surprising that Mendeleyev was out of touch with all the developments in chemistry in Western Europe in the 1860s.7 He was born at Tobol’sk, in Siberia, on 7 February 1834 (27 January on the Old Style calendar still in use in Russia then), the youngest of fourteen children. Their father, Ivan Pavlovich, who was the head of the local school, went blind when Dmitri was still a child, and thereafter the family was largely supported by his mother, Marya Dmitrievna, an indomitable woman who set up a glass works to provide income. Mendeleyev’s father died in 1847, and a year later the glass works was destroyed by fire. With the older children more or less independent, Marya Dmitrievna determined that her youngest child should have the best education possible and, in spite of their financial difficulties, took him to St Petersburg. Because of prejudice against poor students from the provinces, he was unable to obtain a university place, but enrolled as a student teacher in 1850, at the Pedagogical Institute, where his father had qualified. His mother died just ten weeks later, but Dmitri seems to have been as determined as she had been. Having established his credentials by completing his training and working as a teacher for a year in Odessa, he was allowed to take a master’s degree in chemistry at the University of St Petersburg, graduating in 1856. After a couple of years working in a junior capacity at the university, Mendeleyev went on a government-sponsored study programme in Paris and Heidelberg, where he worked under Robert Bunsen and Gustav Kirchoff. He attended the 1860 meeting in Karlsruhe where Cannizzaro circulated his pamphlet about atomic and molecular weights, and met Cannizzaro. On his return to St Petersburg, Mendeleyev became professor of general chemistry in the city’s Technical Institute and completed his PhD in 1865; in 1866 he became professor of chemistry at the University of St Petersburg, a post he held until he was forced to ‘retire’ in 1891, although only 57 years old, after taking the side of the students during a protest about the conditions in the Russian academic system. After three years he was deemed to have purged his guilt and became controller of the Bureau of Weights and Measures, a post he held until he died in St Petersburg on 2 February 1907 (20 January, Old Style). He just missed being an early recipient of the Nobel prize – he was nominated in 1906, but lost out by one vote to Henri Moissan (1852–1907), the first person to isolate fluorine. He died before the Nobel Committee met again (as, indeed, did Moissan).

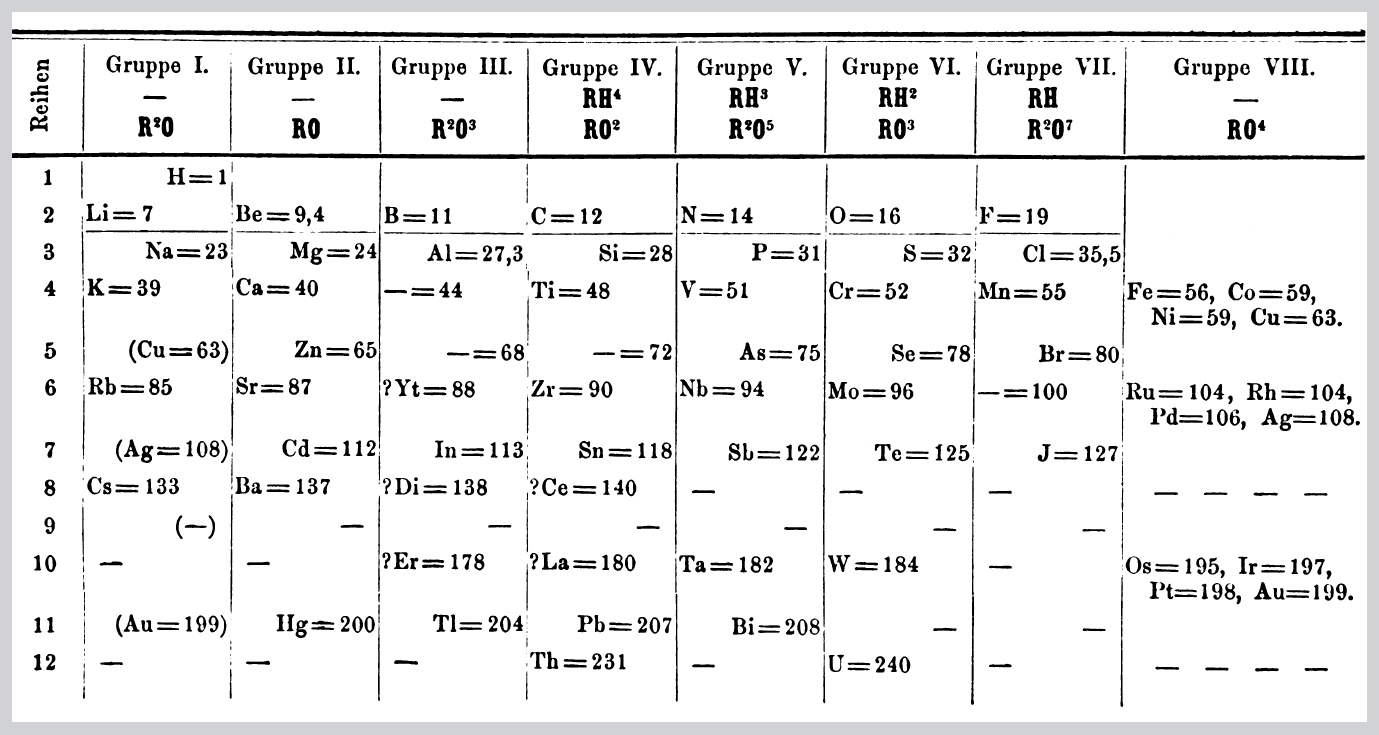

Mendeleyev, like Meyer, made his name by writing a textbook, Principles of Chemistry, which was published in two volumes in 1868 and 1870. Also like Meyer, he arrived at an understanding of the relationship between the chemical properties of the elements and their atomic weights while working on his book, and in 1869 published his classic paper ‘On the Relation of the Properties to the Atomic Weights of Elements’.8 The great thing about Mendeleyev’s work, which singles him out from the pack of other people who had similar ideas at about the same time, is that he had the audacity to rearrange the order of the elements (slightly) in order to make them fit the pattern he had discovered, and to leave gaps in the periodic table, as it became known, for elements which had not yet been discovered. The rearrangements involved really were very small. Putting the elements exactly in order of their atomic weights, Mendeleyev had come up with an arrangement in a grid, rather like a chess board, with elements in rows of eight, one under another, so that those with similar chemical properties to one another lay underneath one another in the columns of the table. With this arrangement in strict order of increasing atomic weights (lightest at the top left of the ‘chess board’, heaviest at the bottom right), there were some apparent discrepancies. Tellurium, for example, came under bromine, which had completely different chemical properties. But the atomic weight of tellurium is only a tiny bit more than that of iodine (modern measurements give the atomic weight of tellurium as 127.60, while that of iodine is 126.90, a difference of only 0.55 per cent). Reversing the order of these two elements in the table put iodine, which has similar chemical properties to bromine, under bromine, where it clearly belongs in chemical terms.

Mendeleyev’s bold leap of faith was entirely justified, as became clear in the twentieth century with the investigation of the structure of the nucleus, which lies at the heart of the atom. It turns out that the chemical properties of an element depend on the number of protons in the nucleus of each atom (the atomic number), while its atomic weight depends on the total number of protons plus neutrons in the nucleus. The modern version of the periodic table ranks the elements in order of increasing atomic number, not increasing atomic weight; but in by far the majority of cases, elements with higher atomic number also have greater atomic weight. In just a few rare cases the presence of an extra couple of neutrons makes the ranking of elements by atomic weight slightly different from the ranking in order of atomic number.

31. Mendeleyev’s early version of the table of the elements, 1871.

If that was all Mendeleyev had done, though, without the knowledge of protons and neutrons that only emerged decades later, his version of the periodic table would probably have got as short shrift as those of his predecessors. But in order to make the elements with similar chemical properties line up beneath one another in the columns of his table, Mendeleyev also had to leave gaps in the table. By 1871, he had refined his table into a version incorporating all of the 63 elements known at the time, with a few adjustments like the swapping of tellurium and iodine, and with three gaps, which he said must correspond to three as yet undiscovered elements. From the properties of the adjacent elements in the columns of the table where the gaps occurred, he was able to predict in some detail what the properties of these elements would be. Over the next fifteen years, the three elements needed to plug the gaps in the table, with just the properties predicted by Mendeleyev, were indeed discovered – gallium in 1875, scandium in 1879 and germanium in 1886. Although Mendeleyev’s periodic table had not gained universal acclaim at first (and had, indeed, been criticized for his willingness to interfere with nature by changing the order of the elements), by the 1890s it was no longer possible to doubt that the periodicity, in which elements form families that have similar chemical properties to one another and within which the atomic weights of the individual elements differ from one another by multiples of eight times the atomic weight of hydrogen, represented a deep truth about the nature of the chemical world. It was also a classic example of the scientific method at work, pointing the way for twentieth-century scientists. From a mass of data, Mendeleyev found a pattern, which led him to make a prediction that could be tested by experiment; when the experiments confirmed his prediction, the hypothesis on which the prediction was based gained strength.

Surprising though it may seem to modern eyes, though, even this was not universally accepted as proof that atoms really do exist in the form of little hard entities that combine with one another in well-defined ways. But while chemists had been following one line in the investigation of the inner structure of matter and arriving at evidence which at the very least supported the atomic hypothesis, physicists had been following a different path which ultimately led to incontrovertible proof that atoms exist.

The science of thermodynamics

The unifying theme in this line of nineteenth-century physics was the study of heat and motion, which became known as thermodynamics. Thermodynamics both grew out of the industrial revolution, which provided physicists with examples (such as the steam engine) of heat at work, inspiring them to investigate just what was going on in those machines, and fed back into the industrial revolution, as an improved scientific understanding of what was going on made it possible to design and build more efficient machines. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, as we have seen, there was no consensus about the nature of heat, and both the caloric hypothesis and the idea that heat is a form of motion had their adherents. By the middle of the 1820s, thermodynamics was beginning to be recognized as a scientific subject (although the term itself was not coined until 1849, by William Thomson), and by the middle of the 1860s, the basic laws and principles had been worked out. Even then, it took a further forty years for the implications of one small part of this work to be used in a definitive proof of the reality of atoms.

The key conceptual developments that led to an understanding of thermodynamics involved the idea of energy, the realization that energy can be converted from one form to another but can neither be created nor destroyed, and the realization that work is a form of energy (as Rumford had more than hinted at with his investigation of the heat produced by boring cannon). It’s convenient to date the beginning of the science of thermodynamics from the publication of a book by the Frenchman Sadi Carnot (1796–1832) in 1824. In the book (Réflexions sur la puissance motive du feu), Carnot analysed the efficiency of engines in converting heat into work (providing a scientific definition of work along the way), showed that work is done as heat passes from a higher temperature to a lower temperature (implying an early form of the second law of thermodynamics, the realization that heat always flows from a hotter object to a colder object, not the other way around) and even suggested the possibility of the internal combustion engine. Unfortunately, Carnot died of cholera at the age of 36, and although his notebooks contained further developments of these ideas, they had not been published at the time of his death. Most of the manuscripts were burned, along with his personal effects, because of the cause of his death; only a few surviving pages hint at what he had probably achieved. But it was Carnot who first clearly appreciated that heat and work are interchangeable, and who worked out for the first time how much work (in terms of raising a certain weight through a vertical distance) a given amount of heat (such as the heat lost when 1g of water cools by 1 °C) can do. Carnot’s book was not very influential at the time, but it was mentioned in 1834 in a discussion of Carnot’s work in a paper by Émile Clapeyron (1799–1864), and through that paper, Carnot’s work became known to and influenced the generation of physicists who completed the thermodynamic revolution, notably William Thomson and Rudolf Clausius.

If Carnot’s story sounds complicated, the way physicists became aware of the nature of energy is positively tortuous. The first person who actually formulated the principle of conservation of energy and published a correct determination of the mechanical equivalent of heat9 was actually a German physician, Julius Robert von Mayer (1814–1878), who arrived at his conclusions from his studies of human beings, not steam engines, and who, mainly as a result of coming at it from the ‘wrong’ direction as far as physicists were concerned, was largely ignored (or at least overlooked) at the time. In 1840, Mayer, newly qualified, was working as ship’s doctor on a Dutch vessel which visited the East Indies. Bleeding was still popular at the time, not only to (allegedly) alleviate the symptoms of illness, but as a routine measure in the tropics, where, it was believed, draining away a little blood would help people to cope with the heat. Mayer was well aware of Lavoisier’s work which showed that warm-blooded animals are kept warm by the slow combustion of food, which acts as fuel, with oxygen in the body; he knew that bright red blood, rich in oxygen, is carried around the body from the lungs in arteries, while dark purple blood, deficient in oxygen, is carried back to the lungs by veins. So when he opened the vein of a sailor in Java, he was astonished to find that the blood was as brightly coloured as normal arterial blood. The same proved true of the venous blood of all the rest of the crew, and of himself. Many other doctors must have seen the same thing before, but Mayer, only in his mid-twenties and recently qualified, was the one who had the wit to understand what was going on. Mayer realized that the reason why the venous blood was rich in oxygen was that in the heat of the tropics the body had to burn less fuel (and therefore consume less oxygen) to keep warm. He saw that this implied that all forms of heat and energy are interchangeable – heat from muscular exertion, the heat of the Sun, heat from burning coal, or whatever – and that heat, or energy, could never be created but only changed from one form into another.

Mayer returned to Germany in 1841 and practised medicine. But alongside his medical work he developed his interest in physics, reading widely, and from 1842 onwards published the first scientific papers drawing attention (or trying to draw attention) to these ideas. In 1848, he developed his ideas about heat and energy into a discussion of the age of the Earth and the Sun, which we shall discuss shortly. But all of his work went unnoticed by the physics community and Mayer became so depressed by his lack of recognition that he attempted suicide in 1850, and was confined in various mental institutions during the 1850s. From 1858 onwards, however, his work was rediscovered and given due credit by Hermann von Helmholtz (1821–1894), Clausius and John Tyndall (1820–1893). Mayer recovered his health, and was awarded the Copley Medal of the Royal Society in 1871, seven years before he died.

James Joule on thermodynamics

The first physicist who really got to grips with the concept of energy (apart from the unfortunate Carnot, whose work was nipped in the bud) was James Joule (1818–1889), who was born in Salford, near Manchester, the son of a wealthy brewery owner. Coming from a family of independent means, Joule didn’t have to worry about working for a living, but as a teenager he spent some time in the brewery, which it was expected he would inherit a share in. His first-hand experience of the working machinery may have fired his interest in heat, just as the gases produced in brewing had helped to inspire Priestley’s work. As it happened, Joule’s father sold the brewery in 1854, when James was 35, so he never did inherit it. Joule was educated privately, and in 1834 his father sent James and his older brother to study chemistry with John Dalton. Dalton was by then 68 and in failing health, but still giving private lessons; however, the boys learned very little chemistry from him, because he insisted on first teaching them Euclid, which took two years of lessons at a rate of two separate hours per week, and then stopped teaching in 1837 because of illness. But Joule remained friendly with Dalton, who he visited from time to time for tea until Dalton’s death in 1844. In 1838, Joule turned one of the rooms in the family house into a laboratory, where he worked independently. He was also an active member of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, where he usually sat (even before he became a member) next to Dalton at lectures, so he was very much in touch with what was going on in the scientific world at large.

Joule’s early work was with electromagnetism, where he hoped to invent an electric motor that would be more powerful and efficient than the steam engines of his day. The quest was unsuccessful, but it drew him into an investigation of the nature of work and energy. In 1841, he produced papers on the relationship between electricity and heat for the Philosophical Magazine (an earlier version of this paper was rejected by the Royal Society, although they did publish a short abstract summarizing the work) and the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society. In 1842, he presented his ideas at the annual meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (the BA), a peripatetic event which happened that year to be in Manchester. He was still only 23 years old. Joule’s greatest work, in the course of which he developed the classic experiment which shows that work is converted into heat by stirring a container of water with a paddle wheel and measuring the rise in temperature, was produced over the next few years, but leaked out in a slightly bizarre way. In 1847, he gave two lectures in Manchester which, among other things, set out the law of conservation of energy and its importance to the physical world. As far as Joule was aware, of course, nobody had done anything like this before. Eager to see the ideas in print, with the help of his brother he arranged for the lectures to be published in full in a newspaper, the Manchester Courier – to the bafflement of its readers and without spreading the word to the scientific community. But later that year the BA met in Oxford, where Joule gave a résumé of his ideas, the importance of which was immediately picked up by one young man in the audience, William Thomson (then 22). The two became friends and scientific collaborators, working on the theory of gases and, in particular, the way in which gases cool when they expand (known as the Joule–Thomson effect, this is the principle on which a refrigerator operates). From the perspective of the atomic hypothesis, he published another important paper in 1848, in which he estimated the average speed with which the molecules of gas move. Treating hydrogen as being made up of tiny particles bouncing off one another and the walls of their container, he calculated (from the weight of each particle and the pressure exerted by the gas) that at a temperature of 60 °F and a pressure corresponding to 30 inches of mercury (more or less the conditions in a comfortable room), the particles of the gas must be moving at 6225.54 feet per second. Since oxygen molecules weigh sixteen times as much as hydrogen molecules, and the appropriate relationship depends on one over the square root of the mass, in ordinary air under the same conditions the oxygen molecules are moving at one quarter of this speed, 1556.39 feet per second. Joule’s work on gas dynamics and, particularly, the law of conservation of energy, was widely recognized at the end of the 1840s (he even got to read a key paper on the subject to the Royal in 1849, no doubt ample recompense for the rejection of his earlier paper), and in 1850 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. Now in his thirties, he achieved nothing else to rank with the importance of his early work, as is so often the case, and the torch passed to Thomson, James Clerk Maxwell and Ludwig Boltzmann.

William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) and the laws of thermodynamics

If Joule had been born with a silver spoon in his mouth and, as a result, never worked in a university environment, Thomson was born with a different kind of silver spoon in his mouth and, as a result, spent almost his entire life in a university environment. His father, James Thomson, was professor of mathematics at the Royal Academical Institution in Belfast (the forerunner of the University of Belfast) when William was born on 26 June 1824. He had several siblings, but their mother died when William was 6: William and his brother James (1822–1892), who also became a physicist, were educated at home by their father, and after the elder James Thomson became professor of mathematics at the University of Glasgow in 1832, both boys were allowed to attend lectures there, officially enrolling at the university (matriculating) in 1834, when William was 10 – although not with the aim of completing a degree but rather to regularize the fact that they were attending lectures. William moved on to the University of Cambridge in 1841, and graduated in 1845, by which time he had won several prizes for his scientific essays and had already published a series of papers in the Cambridge Mathematical Journal. After graduating, William worked briefly in Paris (where he became familiar with the work of Carnot), but his father’s dearest wish was that his brilliant son would join him at the University of Glasgow, and by the time the professor of natural philosophy in Glasgow died (not unexpectedly; he was very old) in 1846, had already begun an ultimately successful campaign to see William elected to the post. James Thomson didn’t live long to enjoy the situation, though; he died of cholera in 1849. William Thomson remained professor of natural philosophy in Glasgow from 1846 (when he was 22) until he retired, aged 75, in 1899; he then enrolled as a research student at the university to keep his hand in, making him possibly both the youngest student and the oldest student ever to attend the University of Glasgow. He died at Largs, in Ayrshire, on 17 December 1907, and was buried next to Isaac Newton in Westminster Abbey.

Thomson’s fame and the honour of his resting place were by no means solely due to his scientific achievements. He made his biggest impact on Victorian Britain through his association with applied technology, including being responsible for the success of the first working transatlantic telegraph cable (after two previous attempts without the benefit of his expertise had failed), and made a fortune from his patents of various kinds. It was largely for his part in the success of the cable (as important in its day as the Internet is at the beginning of the twenty-first century) that Thomson was knighted in 1866, and it was as a leading light of industrial progress that he was made Baron Kelvin of Largs in 1892, taking his name from the little river that runs through the site of the University of Glasgow. Although the peerage came long after his important scientific work, Thomson is often referred to even in scientific circles as Lord Kelvin (or simply Kelvin), partly in order to distinguish him from the physicist J. J. Thomson, to whom he was not related. The absolute, or thermodynamic, scale of temperature is called the Kelvin scale in his honour.

Although he also worked in other areas (including electricity and magnetism, which feature in the next chapter), Thomson’s most important work was, indeed, in establishing thermodynamics as a scientific discipline at the beginning of the second half of the nineteenth century. Largely jumping off from Carnot’s work, it was as early as 1848 that Thomson established the absolute scale of temperature, which is based on the idea that heat is equivalent to work, and that a certain change in temperature corresponds to a certain amount of work. This both defines the absolute scale itself and carries with it the implication that there is a minimum possible temperature (–273 °C, now written as 0 K) at which no more work can be done because no heat can be extracted from a system. Around this time, Carnot’s ideas were being refined and developed by Rudolf Clausius (1822–1888) in Germany (Carnot’s work certainly needed an overhaul; among other things, he had used the idea of caloric). Thomson learned of Clausius’s work in the early 1850s, by which time he was already working along similar lines. They each arrived, more or less independently, at the key principles of thermodynamics.

The first law of thermodynamics, as it is grandly known, simply says that heat is work, and it provides an intriguing insight into the way nineteenth-century science developed that it was necessary, in the 1850s, to spell this out as a law of nature. The second law of thermodynamics is actually much more important, arguably the most important and fundamental idea in the whole of science. In one form, it says that heat cannot, of its own volition, move from a colder object to a hotter object. In that form, it sounds obvious and innocuous. Put an ice cube in a jug of warm water, and heat flows from the warm water to the cold ice, melting it; it doesn’t flow from the ice into the water, making the ice colder and the water hotter. Put more graphically, though, the universal importance of the second law becomes more apparent. It says that things wear out – everything wears out, including the Universe itself. From another perspective, the amount of disorder in the Universe (which can be measured mathematically by a quantity Clausius dubbed ‘entropy’) always increases overall. It is only possible for order to be preserved or to increase in local regions, such as the Earth, where there is a flow of energy from outside (in our case, from the Sun) to feed off. But it is a law of nature that the decrease in entropy produced by life on Earth feeding off the Sun is smaller than the increase in entropy associated with the processes that keep the Sun shining, whatever those processes might be. This cannot go on for ever – the supply of energy from the Sun is not inexhaustible. It was this realization that led Thomson to write, in a paper published in 1852, that:

Within a finite period of past time the earth must have been, and within a finite period of time to come the earth must again be unfit for the habitation of man as at present constituted, unless operations have been or are to be performed which are impossible under the laws to which the known operations going on at present in the material world are subject.

This was the first real scientific recognition that the Earth (and by implication, the Universe) had a definite beginning, which might be dated by the application of scientific principles. When Thomson himself applied scientific principles to the problem, he worked out the age of the Sun by calculating how long it could generate heat at its present rate by the most efficient process known at the time, slowly contracting under its own weight, gradually converting gravitational energy into heat. The answer comes out as a few tens of millions of years – much less than the timescale already required by the geologists in the 1850s, and which would soon be required by the evolutionists. The resolution of the puzzle, of course, came with the discovery of radioactivity, and then with Albert Einstein’s work showing that matter is a form of energy, and including his famous equation E = mc2. All this will be discussed in later chapters, but the conflict between the timescales of geology and evolution and the timescales offered by the physics of the time rumbled throughout the second half of the nineteenth century.

This work also brought Thomson into conflict with Hermann von Helmholtz (1821–1894), who arrived at similar conclusions independently of Thomson. There was an unedifying wrangle over priority between supporters of the two men, which was particularly pointless since not only the unfortunate Mayer but also the even more unfortunate John Waterston had both got there first. Waterston (1811–1883?) was a Scot, born in Edinburgh, who worked as a civil engineer on the railways in England before moving to India in 1839 to teach the cadets of the East India Company. He saved enough to retire early, in 1857, and came back to Edinburgh to devote his time to research into what soon became known as thermodynamics, and other areas of physics. But he had long been working in science in his spare time, and in 1845 he had written a paper describing the way in which energy is distributed among the atoms and molecules of a gas in accordance with statistical rules – not with every molecule having the same speed, but with a range of speeds distributed in accordance with statistical rules around the mean speed. In 1845, he sent the paper describing this work from India to the Royal Society, which not only rejected the paper (their referees didn’t understand it and therefore dismissed it as nonsense) but promptly lost it. The paper included calculations of the properties of gases (such as their specific heats) based on these ideas, and was essentially correct; but Waterston had neglected to keep a copy and never reproduced it, although he did publish related (and largely ignored) papers on his return to England. He also, ahead of both Thomson and von Helmholtz but roughly at the same time as Mayer, had the same insight about the way heat to keep the Sun hot might be generated by gravitational means. With none of his work gaining much recognition, like Mayer, Waterston became ill and depressed. On 18 June 1883, he walked out of his house and never came back. But there is a (sort of) happy ending to the story – in 1891, Waterston’s missing manuscript was found in the vaults of the Royal Society and it was published in 1892.

James Clerk Maxwell and Ludwig Boltzmann: kinetic theory and the mean free path of molecules

By then, the kinetic theory of gases (the theory treating gases in terms of the motion of their constituent atoms and molecules) and the ideas of statistical mechanics (applying statistical rules to describe the behaviour of collections of atoms and molecules) had long been established. The two key players who established these ideas were James Clerk Maxwell (who features in another context in the next chapter) and Ludwig Boltzmann (1844–1906). After Joule had calculated the speeds with which molecules move in a gas, Clausius introduced the idea of a mean free path.10 Obviously, the molecules do not travel without deviation at the high speeds Joule had calculated; they are repeatedly colliding with one another and bouncing off in different directions. The mean free path is the average distance that a molecule travels between collisions, and it is tiny. At the annual meeting of the BA in 1859 (held that year in Aberdeen), Maxwell presented a paper which echoed (without knowing it) much of the material in Waterston’s lost paper. This time, the scientific world was ready to sit up and take notice. He showed how the speeds of the particles in a gas were distributed around the mean speed, calculated the mean velocity of molecules in air at 60 °F as 1505 feet per second and determined the mean free path of those molecules to be 1/447,000 of an inch. In other words, every second each molecule experiences 8,077,200,000 collisions – more than eight billion collisions per second. It is the shortness of the mean free path and the frequency of these collisions that gives the illusion that a gas is a smooth, continuous fluid, when it is really made up of a vast number of tiny particles in constant motion, with nothing at all in the gaps between the particles. Even more significantly, it was this work that led to a full understanding of the relationship between heat and motion – the temperature of an object is a measure of the mean speed with which the atoms and molecules that make up the object are moving – and the final abandonment of the concept of caloric.

Maxwell developed these ideas further in the 1860s, applying them to explain many of the observed properties of gases, such as their viscosity and, as we have seen, the way they cool when they expand (which turns out to be because the atoms and molecules in a gas attract one another slightly, so work has to be done to overcome this attraction when the gas expands, slowing the particles down and therefore making the gas cooler). Maxwell’s ideas were taken up by the Austrian Ludwig Boltzmann, who refined and improved them; in turn, in a constructive feedback, Maxwell took on board some of Boltzmann’s ideas in making further improvements to the kinetic theory. One result of this feedback is that the statistical rule describing the distribution of the velocities (or kinetic energies) of the molecules in a gas around their mean is now known as the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution.

Boltzmann made many other important contributions to science, but his greatest work was in the field of statistical mechanics, where the overall properties of matter (including the second law of thermodynamics) are derived in terms of the combined properties of the constituent atoms and molecules, obeying simple laws of physics (essentially, Newton’s laws) and the blind working of chance. This is now seen as fundamentally dependent on the idea of atoms and molecules, and it was always seen that way in the English-speaking world, where statistical mechanics was brought to its full flowering through the work of the American Willard Gibbs (1839–1903) – just about the first American (given that Rumford regarded himself as British) to make a really significant contribution to science. Even at the end of the nineteenth century, however, these ideas were being heavily criticized in the German-speaking world by anti-atomist philosophers, and even scientists such as Wilhelm Ostwald (1853–1932), who insisted (even into the twentieth century) that atoms were a hypothetical concept, no more than a heuristic device to help us describe the observed properties of chemical elements. Boltzmann, who suffered from depression anyway, became convinced that his work would never receive the recognition it deserved. In 1898, he published a paper detailing his calculations, in the express hope ‘that, when the theory of gases is again revived, not too much will have to be rediscovered’. Soon afterwards, in 1900, he made an unsuccessful attempt on his own life (probably not his only unsuccessful suicide attempt), in the light of which this paper can be seen as a kind of scientific suicide note. He seemed to recover his spirits for a time, and travelled to the United States in 1904, where he lectured at the World’s Fair in St Louis and visited the Berkeley and Stanford campuses of the University of California, where his odd behaviour was commented on as ‘a mixture of manic ecstasy and the rather pretentious affectation of a famous German professor’.11 The mental improvement (if this behaviour can be regarded as an improvement) did not last, however, and Boltzmann hanged himself while on a family holiday at Duino, near Trieste, on 5 September 1906. Ironically, unknown to Boltzmann, the work which would eventually convince even such doubters as Ostwald of the reality of atoms had been published the year before.

Albert Einstein: Avogadro’s number, Brownian motion and why the sky is blue