The History of the Book in Byzantium

N. G. WILSON

In the early years of the 4th century AD, the literary world of Greece and Rome experienced the completion of a revolution that had begun some 200 years earlier: from now on the form of the book was no longer the scroll (Lat. volumen), with the text arranged in a series of columns on one side of the papyrus only, but the codex, with pages. The new format had advantages. If one were searching for a particular passage, it was often quicker to find the right page, even if pages were not numbered and had no running titles or headings, than to unwind a scroll to the appropriate point, and the use of both sides of the leaves meant that more text could be written on a given quantity of papyrus or parchment, which now became available as an alternative. This increased capacity ought to have facilitated the preservation of a large proportion of the vast range of Greek literature, especially as papyrus had traditionally been inexpensive and probably still was. Evidently, however, the book trade was not sufficiently organized to deploy the necessary resources. What can now be read is a minute percentage of what was still available then, even despite the loss of a number of early texts. The codex format, however, if the margins were fully used, did permit the preservation of material culled from a wide variety of secondary literature, i.e. ancient scholarly monographs and commentaries, almost none of which have descended as independent texts.

During the millennium of its existence the extent of the Byzantine empire fluctuated greatly, but even after the loss of political control it retained varying degrees of cultural influence in such areas as southern Italy, Sicily, Egypt, the Levant, and the Balkans. From the beginning of the period parchment was adopted with increasing frequency as a more durable, if more expensive, writing material than papyrus. Various scripts were in use for literary texts. Of these, the most calligraphic is the type generally known as biblical uncial or majuscule, seen at its best in the Codex Sinaiticus of the Bible, which can be dated to the middle of the 4th century; but, despite its name, the use of this script was not confined to biblical texts. With the decline of the empire resulting from the Arab conquests, book production suffered; it is not clear, however, to what extent the loss of Egypt in 641 affected the supply of papyrus nor, supposing that it did, whether this was the only or the major factor leading to reduced production. Very few books (or fragments) survive that can plausibly be dated to the second half of the 7th century or any time in the 8th. When signs of a revival appear c.800, it seems likely that the Byzantines were no longer using papyrus in large quantities, but that they were soon able to avail themselves of the introduction of paper, now being produced in the Levant. Nevertheless, information about the supply and price of writing material at this date is almost entirely lacking. A likely conjecture is that shortages led to experiments with styles of script that had hitherto been used in documents rather than literary texts and that could be written with smaller letters. One of these experiments was eventually found to be satisfactory and generally adopted; it has been suggested that this adaptation of cursive script with numerous ligatures combining two or three letters was invented or popularized by monks of the Stoudios monastery in Constantinople, which was noted for its scriptorium from the 9th century onwards. Uncial was gradually abandoned except for a few luxury copies of texts destined for liturgical use.

Book production was determined to a very large extent by religious requirements: copies of the Bible, liturgical texts, lives of saints and sermons by the Cappadocian Fathers and St John Chrysostom survive in considerable numbers. There was also a steady production of texts for use in school, most of which were the classics of ancient pagan literature. Some of these have come down to us in numerous copies, but this is not true of all—the frequently made assumption that each pupil owned a copy of every text in the syllabus is by no means secure. Members of the professions needed their manuals and specialized treatises; higher education, however, was much less well organized than in western Europe and did not develop a pecia system to provide students with copies of essential texts. An educated class that read literature for pleasure scarcely existed. Books seem to have been very expensive. The prices paid by the bibliophile Arethas c.900 for a few admittedly calligraphic copies on good-quality parchment prove that a year’s salary of a low-ranking civil servant would hardly suffice for the purchase of half-a-dozen volumes. Costs may have been reduced as the production of paper increased; paper was fairly widely used in Byzantium as early as the 11th century, though it probably all had to be imported (see 10). Yet the re-use of parchment in palimpsests continued and was not confined to remote or backward regions of the empire—a fact demonstrating that cheap and readily available writing material could not be taken for granted. In these circumstances, one would expect most scribes to save space by using the comprehensive set of abbreviations that was available for grammatical inflections and certain common words or technical terms. For marginal commentaries the use of the abbreviations was an unavoidable necessity, but generally scribes did not resort to this solution for the main text. They tended to use the abbreviations at the end of a line to achieve justification of the margin, which may be a hint that on aesthetic grounds they preferred to avoid them elsewhere.

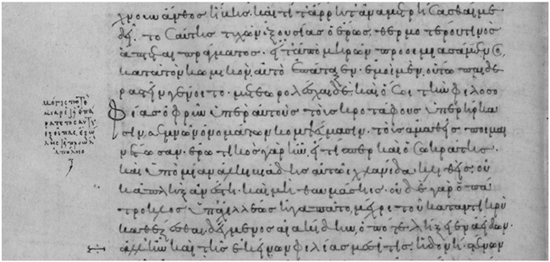

Marginal note by Archbishop Arethas (c.860–c.940) expressing his disgust at Lucian’s apparent confession of homosexuality in his Amores. © The British Library Board. All Rights Reserved. Harley. 5694, fol 97v.

Scribes were not organized as a guild. It is clear that many individuals made their own copies rather than employing a professional. There were some professionals, as can be seen from the occasional colophon in which the writer describes himself (women copyists are almost unknown) as a calligrapher; it was possible to earn one’s living in this way, but probably not many did so. Some large monasteries (e.g. the Stoudios monastery) had a scriptorium and presumably accepted commissions from external customers; many colophons state that the copyist was a monk. Colophons by Greek scribes are not as frequent or informative as those found in Armenian MSS, however, and so we know relatively little about Greek scribes. A further consequence of this is that it is often impossible to determine in which part of the empire a book was written, because there are only a limited number of cases in which the script gives a clear indication, whereas with Latin MSS it is usually not very difficult to identify the country of origin, and sometimes much greater precision about a MS’s provenance can be achieved.

A tantalizing glimpse of the workings of a scriptorium is provided by the rules drawn up for the Stoudios monastery by St Theodore (759–826). There is mention of a chief calligrapher, who is responsible for assigning tasks fairly, preparing the parchment for use, and maintaining the binder’s tools in good order. There are penalties for him and for monks who misbehave or fail to perform their duties, e.g. if a scribe breaks a pen in a fit of anger. Inter alia the scribe is required to take care over spelling, punctuation, and diacritics, to stick to his own task, and not to alter the text he is copying. What is not stated is whether a scribe was expected to copy a certain number of pages each day, and how much the house charged external purchasers. There is no reference to illuminators, but scanty evidence from other sources suggests that they may have had independent workshops.

Calligraphy does not appear to have been appreciated in Byzantium as an art in the same way as in some other cultures; but the use of the term by scribes is proof that some clients had a high regard for their services, and many extant MSS are marvels of elegant script with a uniformly high standard maintained for several hundred pages—a striking example is the Euclid written for Arethas in 888 by Stephen the cleric (who as it happens does not call himself a calligrapher in the colophon). It is also clear that, for biblical and other religious texts, there was an expectation that formal script would be used, and generally such books, even if not elegantly written, exhibit a presentable standard of penmanship. This requirement went hand in hand with a conservative tradition characteristic of Byzantine culture: an archaizing tendency detectable in the early years of the Palaeologan period (c.1280–c.1320) led to the production of many copies, mainly but not exclusively of religious texts, that at first sight look a good deal earlier and as a result used to be incorrectly dated to the 12th century. Nevertheless, schoolteachers and other professionals making copies intended primarily for personal use were often content to write a less formal hand with many cursive elements and abbreviations; these scripts too have often been wrongly dated. In many cases, there is enough individual character in them to permit identification of the writer. A very neat example of this type of script with extremely lavish use of abbreviations is seen in various volumes penned by Eustathius, the lecturer at the patriarch’s seminary in the capital, who c.1178 became archbishop of Salonica. Much less legible is the protean hand of a 12th-century grammarian called Ioannikios, who can be identified as the scribe of nearly twenty extant MSS, containing predominantly works by Galen and Aristotle, some of which were probably commissioned from him by the Italian translator Burgundio of Pisa.

Circulation and trade are topics about which information is inadequate. The 6th-century lawyer and historian Agathias speaks of bookshops in the capital and there are occasional later references to booksellers. Yet it is curious that a society which attached great importance to the written word and devoted care to the education of imperial and ecclesiastical administrators capable of drafting documents in formal archaizing prose has left so little record of this and other related matters. It is fairly clear, however, that a desire to obtain unusual texts could not normally be satisfied by a visit to a neighbouring shop, even if one lived in the capital of the empire.

The Byzantines called themselves Romans, but understood that they were custodians of the Greek literary heritage; in most of their own writings they did their best to imitate the language and style of the Greek classics. One has to ask how far they succeeded in preserving the stock of Greek literature they had inherited in late antiquity. Already by this date a number of classical texts were no longer in circulation; the destruction of the library at the Serapeum in Alexandria in 391 will no doubt have led to further losses. Though there is very little historical evidence on these matters, it seems that the emperors never succeeded in maintaining a substantial library comparable to those found in the great cultural centres of the ancient world; a monastery with a collection of several hundred volumes such as St John on Patmos was unusually well provided for (an inventory made in 1201 lists 330 items), and a library of fewer than 100 books might be reckoned perfectly satisfactory. The Byzantines would have needed much greater resources than they disposed of in order to conserve a high proportion of the texts that were still extant. For a time they had partial success: Photius in the middle of the 9th century was still able to locate—it is not known how or where—copies of many important works, especially historical texts that no longer survive today. Probably the copies he consulted were already unique, and if they were not texts of orthodox theological content, there was always a risk that they might be discarded by a reader anxious to make a palimpsest copy of some work of seemingly greater relevance (a notorious example is the palimpsest in which liturgical texts have been written over unique treatises by Archimedes, fragments of the Athenian orator Hyperides, and a hitherto unknown commentary on Aristotle’s Categories). Copies of rare works that had not suffered such a fate or been destroyed by accident mostly disappeared in 1204 when the Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople. After that date, the range of works available was essentially the same as can now be read in earlier medieval copies. When the Turks took the Byzantine capital in 1453, there were few if any texts, the loss of which we should now regret, lurking in the libraries in Constantinople.

[Dumbarton Oaks Colloquium,] Byzantine Books and Bookmen (1975)

N. Wilson, ‘The Libraries of the Byzantine World’, Greek Roman and Byzantine Studies, 8 (1967) 53–80 (repr. with addenda in Griechische Kodikologie und Textüberlieferung, ed. D. Harlfinger (1980), and further addenda (in Italian translation) in Le biblioteche nel mondo antico e medievale, ed. G. Cavallo (1988)

—— ‘The Manuscripts of the Greek Classics in the Middle Ages and Renaissance’, Classica et Medievalia, 47 (1996), 379–89

——The Oxford Handbook of Byzantine Studies (2008), 101–14, 820–5