Chapter Seven Surprising Days

If you are a certain kind of person, you’ll be surprised to learn that Fred’s strategy for escaping the dungeon did not work. If you are another kind of person, you will not be surprised. Most people start out as the first kind of person—full of hope—but eventually grow up into the plain old second kind—the kind that doesn’t get surprised, and doesn’t feel hope. Some folks believe that not being surprised—or at least not admitting to being surprised—is a sign of being grown up. I disagree with those people. But no one’s asking for my opinion.

Fred thought she was the second, grown-up kind of person—but it turned out she was really the first kind. She was surprised. Another word for surprised is disappointed.

When Fred opened her eyes, she was still in her planet pajamas and fuzzy bunny slippers (comforting) and still in a dungeon with Downer (not so comforting). She was definitely not back home. Not even in her bland, new home with an enormous paper lantern in the middle of the living room, a paper lantern standing there with some kind of unreadable conviction, if something made out of paper can be said to have conviction.

Fred had conviction. She took off one of her slippers and threw it hard against a wall. “Drat and double drat!” she shouted. “Triple drat and drat, drat, drat!” This went on for a while.

“Don’t be mad at the Rat,” the elephant said finally. “We have the Fearsome Ferlings to blame. Be mad at the Ferlings!”

Fred didn’t know (yet) what a Ferling was. But as the red fury passed, she started to feel a feeling that was not unlike the feeling of it being more than forty-five minutes since the school day has ended and still no one has arrived to pick you up. Fred sat on a pile of hay and leaned against Downer’s broad and wrinkled leg. The sad face of the deer on the WANTED poster seemed to regard her with pity.

Downer said gently, “I know being here with me isn’t what you want. Would it make you feel better if I told you that the Rat promised I would be freed within a week?”

Fred brushed hay off her planet pajamas, straightened her posture, wiped her eyes with her sleeve. “Why didn’t you mention that before?”

“Because it’s not going to happen,” Downer said.

“You just said it was going to happen.”

“What I said was that the Rat said it was going to happen.”

Downer’s eyelashes no longer looked beautiful to Fred, but instead like the bristles of an old dustpan brush. “You told me the Rat is always right, and righteous, and—”

“That is correct.”

“But somehow she’s wrong?”

“Incorrect.”

The two of them were like characters in an equation proving that if you lock up two creatures in a small space, at some point they will begin to bicker like siblings. Or maybe that’s not the equation—siblings, of course, would begin to bicker right away.

“Are you saying the Rat is not… reliable?” Fred asked. Reliable was a word Fred was attuned to because her mom, after being more than forty-five minutes late picking Fred up from school for the third day in a row, had promised to become more reliable. And later, when her mom had given her only a day’s warning about switching schools, she had again said she would try to be more reliable.

“Oh, the Rat is perfectly reliable. I mean, she’s the Rat of Reasoning and Rationality, of Rockets and Ribonuclease Inhibitors and….” Downer twirled his bright umbrella briefly, but then set it back down. “You get the idea. She’s perfectly reliable. And that’s the problem.”

“I’m losing track of what the problem is. I thought the Rat being held captive in the Bag was the problem.”

“Nope.”

“Or that nobody loves you?”

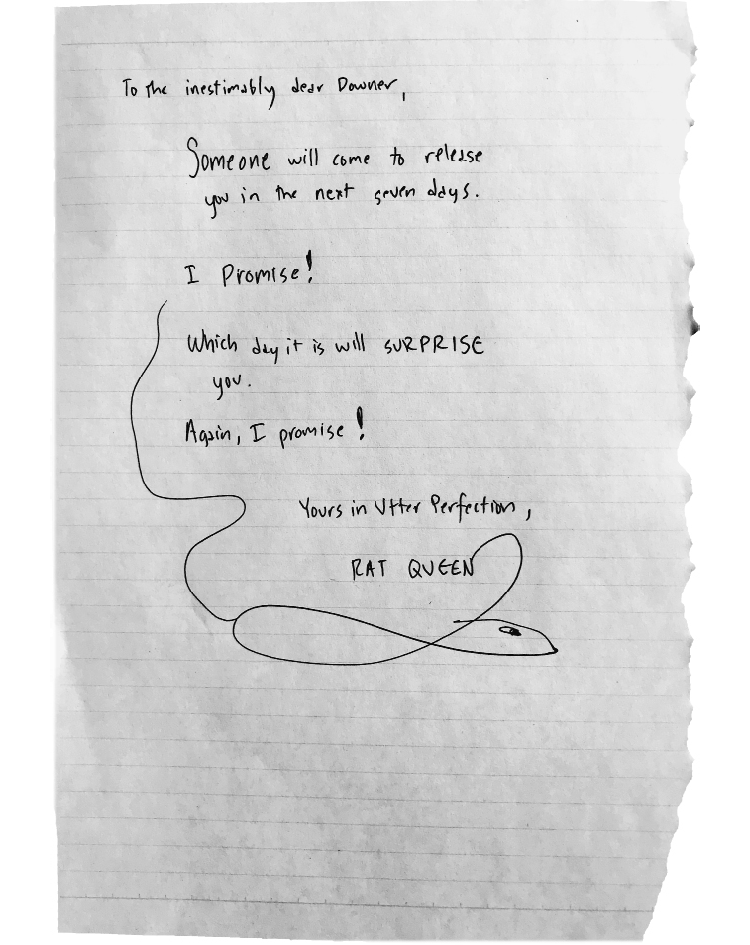

Downer shook his head again. In a dejected voice, he said, “Take a look for yourself.” Downer showed Fred a handwritten note:

Fred smiled. “It’s a little kooky, but this does make me feel more hopeful.”

“You feel hopeful because you aren’t thinking. Unfortunately, I excel at thinking.”

“What’s the problem now?” Fred asked.

“Think about it. The note says I’ll be surprised by the day of my release. Got that?”

“Yes…. So?”

Downer shook his head, flapping his tremendous ears. “Think. I know that I won’t be freed on the seventh day. How do I know this?” Using his umbrella, Downer scratched a chart into the dirt floor, with boxes around each of the numbers one to seven. “Because by the sixth day, I would know that I was going to be freed on the seventh day. Then the seventh day wouldn’t be a surprise, right? The note clearly states that I will be surprised. So we can rule out Day Seven.” He X-ed out the number seven box.

“Fine,” Fred said. “There are still all the other days.” Her stomach growled. She hoped it wouldn’t be too long before a peanut butter and pickle sandwich presented itself.

“But if Day Seven is ruled out, then it can’t be Day Six. Do you see why? We’ve ruled out Day Seven, so by Day Five, if I still haven’t been freed, I would know it would be Day Six, so Day Six also wouldn’t be a surprise. No Day Six.” He X-ed out the Day Six box. “Once you’ve ruled out Days Six and Seven, you have to rule out Day Five, because it’s now the Last Day, and being released on the Last Day will never come as a surprise. Same thing with Day Four. And Day Three, and so on. So none of the days can be surprising. Get it?”

“Not really. You’re saying we’re going to die in here because of a logic problem?”

Downer’s voice grew angry. “If the Rat said it was going to be a surprise, it’s definitely going to be a surprise. The Rat always means what she says.”

“Maybe you’re taking the surprise thing too seriously,” Fred suggested. She wished her mom were here, so she and Downer could get help with the logic, or nonsense, of the Rat’s note.

“No,” Downer said flatly.

“Or there’s been a mistake,” Fred argued. “The Rat could have said you guys and whoever wrote it down for her misheard it as surprise. Or the Rat wanted to say you will be pleased but wrote you will be surprised because, well, maybe at that moment she was thinking of a side of French fries…. The possibilities are endless.”

“Mm, yeah… I don’t think so,” Downer said. He drew a big, doleful X over his entire dirt diagram.

“You are a downer,” Fred said. Then, with sudden energy, she exclaimed, “But hey—what about me?”

“You mean—you’re the surprise?” Downer asked. “I was thinking—”

“No. I mean the letter doesn’t say anything about me. Will someone come and get me?”

“Well, what did the Rat tell you?”

“The Rat didn’t tell me anything! I told you I don’t know the Rat, I’ve never spoken to the Rat. I’ve never spoken to any rat.” (Except sleepy Edison, with whom she had actually shared a fair number of her troubles, but Edison never spoke back, so Fred figured that didn’t count.) “I’ve never even spoken to an elephant before now. Let alone such a gloomy one. This is worse than moving to a new town. This is terrible. This is a real pickle.”

“It’s not a real pickle, it’s a metaphorical pickle.”

“You know what I mean—”

“But why say real pickle precisely when you mean not a real pickle, and—”

Fred and Downer began to panic, and to bicker, and to bicker more and panic more, arguing about what was or wasn’t a pickle, and what was or wasn’t surprising, and who was or wasn’t going to be going where, and when, and how you can even count days when you can’t keep track of time, and as they argued they were once again proving the equation about two creatures locked in a small room for long enough—

When there came a knock at the door. Or, you might even say, a Knock, Knock at the door.