For thousands of years getting food was a vigorous, Neurobic workout, involving all the different senses: tracking animals by sight, smell, and sound…deciding when to plant or harvest crops by “reading” the weather…remembering how to locate the best fishing and gathering grounds. Each season presented its own challenges and opportunities for obtaining food, and the fear of going hungry always loomed just over the horizon. Finding food was never routine and it was usually a very social activity. (It is believed that language first originated on the hunt.)

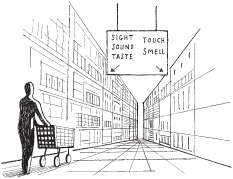

Modern society has effectively eliminated the time, struggle, and unknowns involved in getting food, but we’ve given up something in exchange for the predictability and convenience of the supermarket. Instead of food being a feast for the senses, supermarket packaging is geared to appeal mainly to our visual sense. And in this world of shrink-wrapped, frozen, or canned foods, stimulation based on other senses, such as taste, touch, and smell, are eliminated or relegated to the background. Human exchange has been replaced by automated checkouts, and even the hunting routes (aisles and shelf arrangements) have been preprogrammed for optimum sales, not sensory stimulation.

The exercises in this section attempt to reawaken the hunter-gatherer within, by involving more of your senses and the associations between them, as well as some of the social aspects of the “hunt.”

These activities may involve a little extra time (and in some cases, a bit more money), but they have big payoffs in terms of nourishing the brain.

Since the produce is usually what’s available locally and in season, you never know what to expect. Go to the market in an exploratory mode—with no list—and invent a meal from whatever you find that looks, smells, and feels good.

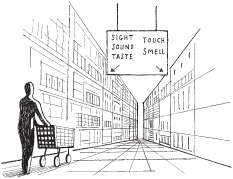

Let’s see how a farmers market recruits your senses during apple season. You stop at a farm stand on a fall drive and browse among the varieties of apples available. As you explore the diversity of shapes and colors, pick up an apple of each variety. Feel it for texture and firmness, inhale its aroma. Let the proprietor cut open a Macoun for you to taste, and another apple you’ve never seen before—an heirloom from his grandfather’s orchard that he’s been growing for thirty-seven years. You taste the subtle tartness, experience the difference between mealy, juicy, and crisp. Suddenly you are more acutely aware that it’s a bright, sunny day, the leaves are changing, there is a smell of fermenting apples in the air, and the sky is a bright blue. Around the one simple act of buying some apples, you have created a rich tapestry of memory.

Chances are the vendors are also the people who grow the apples, and you’re sure to encounter some interesting stories and characters. Ask about their farms; this year’s crop; and if there’s a favorite recipe that uses what you’re buying.

This exercise ranks high on all the elements of Neurobic requirements: Novelty, multisensory associations between different shapes, colors, smells, and tastes, as well as social interaction.

An Asian, Hispanic, or Indian market will offer a wide variety of completely novel vegetables, seasonings, and packaged goods depending, of course, on your own ethnic background. Choose a cuisine unfamiliar to you. Ask the storekeepers how to prepare some of the unfamiliar foods on the shelves.

Spend some time in the spices section. Different cultures use radically different seasonings, and you’re likely to encounter smells and tastes that you’ve never experienced.

If you’re lucky, the market will have self-serving bins of grains, beans, cereals, and spices. Buy a few small bags of anything that strikes your fancy to use later as tactile, taste, or olfactory stimuli.

The olfactory system can distinguish millions of odors by activating unique combinations of receptors in the nose. (Each receptor is rather like a single note on a piano, while the perception of an odor is like striking a chord.) Encountering new odors adds new chords into the symphony of brain activity. And because the olfactory system is linked directly to the emotional center of the brain, new odors may evoke unexpected feelings and associations, including links to the ethnic group involved.

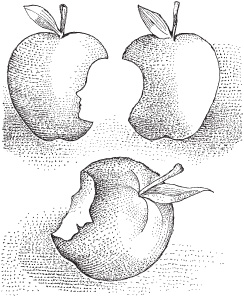

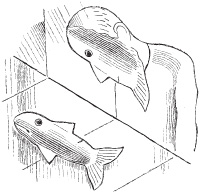

You may not have ethnic markets where you live. But most places still have specialty stores staffed by people who know about the products they sell. Ask to see, feel, and smell the merchandise, and about where it came from or how to prepare it. In a fish store, by seeing, feeling, touching, and smelling the catch, you form associative links with the variety of shapes, sizes, and colors.

In a bakery, your olfactory sense gets a valuable workout. Certain odors, such as freshly baked bread, trigger emotional responses that stimulate the memory of other events.

A package of sliced monk-fish looks like a hundred other shrink-wrapped packages, but a whole monkfish—a bizarre, almost grotesque creature—is deeply memorable.

Use your senses. Close your eyes and distinguish fruits by their smell or by the feel of their rinds. Use self-serve bins to buy small amounts of grains, cereals, or spices with different tastes, textures, or odors (health food stores are especially good sources).

Use your senses. Close your eyes and distinguish fruits by their smell or by the feel of their rinds. Use self-serve bins to buy small amounts of grains, cereals, or spices with different tastes, textures, or odors (health food stores are especially good sources).

Change your usual route through the aisles.

Change your usual route through the aisles.

Ask the people at the meat, fish, or deli counters to help you choose something instead of just picking out prepackaged foods.

Ask the people at the meat, fish, or deli counters to help you choose something instead of just picking out prepackaged foods.

Change the way you scan the shelves. Stores are designed to have the most profitable items at eye level, and in a quick scan you really don’t see everything that’s there. Instead, stop in any aisle and look at everything displayed on the shelves, from top to bottom. If there’s something you’ve never seen before, pick it up just to read the ingredients and think about it (you don’t have to buy it). You’ve broken your routine and experienced something new.

Change the way you scan the shelves. Stores are designed to have the most profitable items at eye level, and in a quick scan you really don’t see everything that’s there. Instead, stop in any aisle and look at everything displayed on the shelves, from top to bottom. If there’s something you’ve never seen before, pick it up just to read the ingredients and think about it (you don’t have to buy it). You’ve broken your routine and experienced something new.

Each season, you can gather edible plants, fruits, and nuts in the wild—fiddlehead ferns, dandelions, wild asparagus, and grape leaves, various wild berries, mushrooms (careful!), chestnuts, sea wort, wild peas. (If you don’t know what things are okay to eat or how to prepare them, take a field guide to edible plants with you on your foraging trips.)

Visit a pick-your-own orchard or farm to gather strawberries, blueberries, corn, or pumpkins. Make the “harvest” a social event by taking along kids or friends.

Another variation is to shop without a list and plan a meal from what looks good at the market that day.

Adult brains tend to use the simplest, fastest route to identify objects, while infants and children more often use several senses. Searching for food in the wild prevents the brain from using the easy way out, and hones its ability to make fine discriminations. Is that round green thing a fiddlehead fern (good) or a skunk cabbage sprout (bad)? Without bins, packages, and labels, your brain is forced to pay attention to every cue available in the natural environment.

Have your spouse or a friend make a list of foods to buy using only descriptors, not the name of the food. For example: “It’s about the size and shape of a soccer ball, tannish, heavily veined, dimpled on one end, should feel slightly soft and have a heavy aroma.”

If one of you makes the list and the other shops for it, you’ll both earn Neurobic benefits by tapping into all the sensory association pathways linked to a particular food.

An old-fashioned hardware store (as opposed to a superstore) is more apt to have employees who really know tools and can talk about how to use them. Instead of being shrink-wrapped, everything—from screws to nuts—can be touched and held. Try stopping in for a Neurobic approach to home improvement.

Or explore a flea market, which ranks high on novelty and the possibilities for social interaction.

Similarly, shopping occasionally at a small bookstore offers more opportunities for genuine social interactions with “book people.” You’re more likely to encounter recommendations from the staff related to your interests, opening up a whole new reading adventure: “If you like this author, why not try…”