4

Emerging Powers

The Hype of the Rest?

The terms “emerging powers” and “rising powers” recognize the growing economic as well as political and strategic status of a group of nations, most if not all of which were once categorized (and in some accounts still are) as part of the “third world” or “global South.” The definition of who belongs in these categories is neither fixed nor uncontroversial. These terms are often used to include countries such as the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), as well as Indonesia, Mexico, Argentina, Australia, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, and Turkey. Andrew Cooper has observed that “the depiction of rising powers” has been “expansive, fluid, and contested … No one acronym has the field to itself.”1 The same can be said of the term “emerging powers.” For example, despite its seeming conflation with “emerging powers,” the term “rising powers” is normally associated with countries that have a clear potential to become great powers, such as China, India, and Brazil. The term “emerging powers” indicates countries such as Indonesia, South Korea, Mexico, Nigeria, and South Africa, which are not perceived to be headed for international great power status. (For convenience, I will use the term “emerging powers,” a broader category which subsumes “rising powers.”) Russia is an odd presence in the ranks of the rising/emerging powers category, since it is really a traditional European great power, which was also a military superpower during the cold war. Some analysts even see it, at least in terms of its geopolitical behavior, as an “outdated great power.”2 Another term that complicates the picture is that of “regional powers,” a category that relies more on physical and material attributes of a country relative to its immediate neighbors. Not all emerging powers are counted as regional powers, though. For example, should South Korea and Argentina, while recognized as emerging powers, be counted as regional powers? These uncertain and contested categorizations are important, as they affect the discussion of their role in the world governance and order.

The popularity of the idea of emerging powers had much to do with the term “BRIC” – Brazil, Russia, India, China. This was a term coined by a Goldman Sachs analyst in 2001 in the context, it must not be forgotten, not of describing their power in global order, but in describing the potential of the “emerging market economies” in relation to their investors in 2001.3 South Africa joined the group in 2010, thus making it “BRICS.” In a 2010 report, Goldman Sachs defended the concept by pointing out that over the preceding 10 years BRIC had contributed over a third of world GDP growth and had grown from a sixth of the world economy to almost a quarter (in PPP terms). Its projections envisaged the BRICS, as an aggregate, overtaking the US by 2018.4

The Goldman Sachs analyst, Jim O'Neill, is now less bullish about the economic prospects of the BRICS. But the fashion show continues with new acronyms such as CIVETS (Colombia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Egypt, Turkey, and South Africa), “breakout nations”5 (Turkey, the Philippines, Thailand, India, Poland, Colombia, South Korea, and Nigeria). Another one is MIST (Mexico, Indonesia, South Korea, and Turkey). How much of this is a self-promoting marketing ploy by business consulting firms is a moot question.

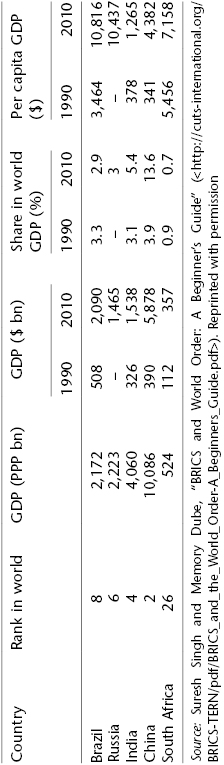

To some extent, recognition as an emerging/rising power is decided by membership in clubs, the most well known of which is the BRICS. But there are other club designations, some of them largely notional, such as BRIICS (including Indonesia), BASIC (BRIC minus Russia, but with South Africa), while others are functioning, such as IBSA (India, Brazil, South Africa), BRICSAM (add South Africa and Mexico). At a broader level, the key point of reference is the G-20,6 a club known for its importance in global finance, membership in which almost automatically earns a country the label of “emerging power.” Even in economic terms, the category of emerging powers is not homogeneous. This is true even of the relatively compact group of the BRICS (now with the addition of South Africa), as table 4.1 shows.

Table 4.2 Economies of G20 members (2009 estimated)

For the most part, membership is based on traditional indices of power, or on material capabilities, primarily economic but also military, as well as the relative size and population of nations. Each BRICS member is a significant military power, especially relative to its own neighbors. Membership in these clubs does not necessarily recognize soft power, or leadership in ideas, innovation, and problem-solving, or what might be called intellectual and entrepreneurial leadership. This leaves out a few countries known for their global and regional leadership role, past and present, and raises questions about how meaningful the term “emerging power” is, as a new force in world politics. For example, Singapore is left out of these emerging power clubs, yet it is an enterprising nation when it comes to Asian and global economic cooperation. Angry at its exclusion from the G-20, Singapore helped to found a global governance group at the UN. Costa Rica under Oscar Arias was a key player in resolving the Central American conflict in the 1980s. Thailand founded ASEAN, one of the most successful regional groupings in the developing world. Despite its initial economic focus, the G-20 has aspirations to manage security issues. Yet some of the most important security actors of the developing world, such as Egypt and Nigeria, are not part of it.

Despite these problems, the term “emerging powers” has secured for itself a prominent place in the discussion of the developing world order. But while there is a good deal of noise about the emerging powers, mostly created by the powers themselves, the analysis of their role has been shaped by a narrow and short-term policy focus, much of it having to do with the global economic crisis since 2008. There is less accounting of the gap between their aspirations and capabilities, on the one hand, and between the benefits they bring into and the burdens they impose on “global governance” and order, on the other hand.

The G-20: Promise and Performance

There are two main candidates vying for the status of being the most important member of the new global power elite, the BRICS and the G-20. Although the BRIC idea goes back to 1990, and the G-20 was established in 1999, a turning point in their role in global reordering came with the outbreak of the global financial crisis in 2008. The crisis led this select group of states not only to play a major role in fashioning the global response to the crisis, but also created opportunities for them to shape the debate over the future of global governance and world order.

However, this has not been a smooth sailing. BRICS has the advantage of being a small and compact group. But economic disparities (already mentioned) aside, its members are also divided in terms of their domestic political systems – between democratic Brazil, India, and South Africa on the one hand, and China's communist regime and Russia's authoritarian turn on the other. One consequence of this is that the BRICS group is open to criticism for ignoring democratic issues even as they demand greater democratization of international relations. For example, by joining the BRICS, South Africa was seen as placing power and self-interest over principles that it had espoused as a member of IBSA, with India and Brazil, including a commitment to human rights and democracy not shared by BRICS members China and Russia. Three of the BRICS members – Russia, China, and India – are nuclear weapon states while South Africa and Brazil are not, the latter having renounced nuclear weapons earlier. Hence attitudes toward nuclear non-proliferation within the BRICS are not convergent.

More importantly, the BRICS countries do not seem to have enough cement to hold them together on the key issue of global reordering. A key example is the competitive relationship between China and India. And the discordant voices within the grouping about issues of global order, ranging from climate change to UN Security Council reform (especially between India and China), has not helped the group to project an image of coherence and credibility. Commenting on intra-BRICS differences, a Chinese analyst asks, “Why does it put Brazil, Russia, India, and China together and coin a new word? These four countries are actually quite different from each other in many ways and even in fundamental nature.”7 Thus, these differences do undermine their collective clout in international affairs. It is a fair question whether, despite the hype surrounding it, membership in the BRICS is more of a status symbol (and a way of attracting attention from foreign investors) than a means to real decision-making authority in global affairs.8

The G-20 is perhaps a more credible agent for reshaping global governance. This group represents 80 percent of the world's population, 90 percent of the world's GDP, 90 percent of the world's finance, and 80 percent of the world's trade. It is credited with “implementing the largest coordinated macroeconomic stimulus in history, which has successfully arrested a potentially deep global recession.”9 Largely because of its success in arresting the financial crisis, this institution has described itself (at its Pittsburg Summit in September 2009) as the “world's premier forum for international economic cooperation.”10 The former EU foreign policy chief, Javier Solana, calls it the “only force in which world powers and the emerging countries sit as equals at the same table.”11 Others see it as having the “potential to alter the international order almost by stealth.”12

Supporters of the G-20 see many benefits coming from its role in global governance. Bruce Jones argues that it can make the UN more effective by bridging the gap between the governing mechanisms of the secretariat and those of the specialized agencies, like the IMF and World Bank. It can also make coordination between the UN's security and economic groupings, for example, the Security Council and ECOSOC, easier. This might help with the prospects for the management and resolution of regional conflicts like those in the Middle East and Asia. It can stimulate discussion and debate over global issues, and get other multilateral bodies to act faster and better “extract excellence” from them.13

A key part of the agenda of the G-20 includes reform of global institutions. Here the emerging powers are on solid ground. The major global institutions – the UN, IMF, and World Bank, etc., – were created in the aftermath of World War II and reflected the capabilities and influence of nations in that era. That their future effectiveness and legitimacy depends on adapting to the new realities of the twenty-first century cannot be seriously questioned.

The G-20 has the potential to advance the reform of global governance. It certainly gave a new lease of life to debate over reform of global institutions like the IMF and the World Bank, including the initial step taken in 2010 by IMF members to adjust its members' voting quotas marginally in favor of the developing countries (which places Brazil, China, India, and Russia among the 10 top shareholders of the IMF),14 and move toward a fully democratically elected executive board.

But, overall, the G-20 has made little headway on the reform of global institutions. The political and practical obstacles to making global institutions more democratic and inclusive are huge. Expanding and reforming the UN Security Council, especially its veto system, has proven to be virtually impossible. The actual changes induced by the G-20 in the global governance system are still marginal. The reason for this is not just resistance from the West, although this is a factor. It has also to do with disunity within the ranks of the G-20, and not just between India and China or China and Japan. For example, the immediate regional rivals of Nigeria, Brazil, and India have vigorously opposed other countries' quest for a permanent seat in the UN Security Council. “Egypt and South Africa wonder about Nigeria's special qualifications, while Argentina and Mexico, Indonesia and Pakistan question the choice of Brazil and India. Smaller countries, in turn, are unhappy about any system that will strengthen the powerful at their expense.”15 Another recent example is the failure of the G-20 to put up a common candidate from the ranks of the developing countries, and Brazil's refusal to back up a Mexican candidate, which might have helped keep the position of the IMF chief in the hands of the French as Christine Lagarde replaced Dominique Strauss-Kahn.16

Moreover, questions remain as to the effectiveness and legitimacy of the G-20 in the whole new architecture of global order. Despite the credit it receives for its role in managing the 2008 global financial crisis, the group's contribution to the long-term health of the global economic system remains questionable. As Malaysian economist Mahani Zainal Abidin argued, the G-20 has not effectively addressed “fundamental issues – such as the global imbalances, exchange rate alignment, preventing bubbles, and discouraging excessive risk taking.”17 There are also questions and uncertainties concerning its institutionalization (it still lacks a secretariat). Its credibility has been marred by a lack of continuity from one summit to the next. It is also not clear whether the G-20 would replace the G-8. As Solana put it, “holding a G-8 summit just before a G-20 summit … simply serves to prolong the maintenance of separate clubs, which is unsustainable.”18 Europe is over-represented in the G-20. And countries which should have been in the G-20 are not there. The issue of representation might be addressed through “smart inclusion,”19 including the more universal organizations like the Development Committee of the World Bank, or the IMF's International Monetary and Financial Committee, as well as other regional groupings and organizations such as ASEAN and the African Union. The EU is already included. But the move toward inclusiveness is likely to be controversial.

To date, there is no consensus on whether the G-20 should remain a “crisis committee” (the role played in addressing the 2008 crisis) to deal with financial volatility, or become a more regularized “steering committee” to manage a wider set of issues on a more regular basis. Some view it as a “global focus group” that draws attention to major global concerns. It has been criticized for a “disciplinary, coercive culture” and offers little “evidence of … being a substitute for U.S. hegemonic control.”20 The G-20 has also struggled with agenda expansion beyond finance to include development (e.g., the Seoul Development Consensus adopted at the Seoul Summit in 2010), environment (green growth at the Los Cabos summit in 2012), and security issues. The comparative advantage of the G-20 over other institutions, such as the World Bank, UNSC, and the Rio+20, is still unproven. Taking on too many issues can backfire and compromise its credibility, as happened under the French presidency at Cannes in 2011, with the anti-corruption initiative, food security and financial transaction tax, and so on. In the meantime, the Eurozone crisis has affected its standing negatively, overshadowed by the European Central Bank and the IMF.

The emergence of the G-20 group has larger implications for global order. It has been viewed as the beginning of the end of a structure of global governance dominated by the Western nations and international institutions controlled by them. The G-20 has the potential to blur or bridge the traditional North–South, or West versus the Rest, faultline in world order. For example, on the issue of the IMF governance reform, the US (at least the Obama administration) was aligned with China, India, and Brazil in supporting increased representation of the emerging powers, against Europe, which was resisting any reduction in the number of the European seats.

Are we then witnessing a new spirit of partnership and cooperation between the North and the South, replacing the old mistrust and rivalry? One should be reminded that some of the recent examples of North–South cooperation, whether undertaken by the G-20 or not, are crisis-induced. Such examples, aside from the 2008 financial crisis, might include 9/11, Somali pirates, and Libya – although in Libya's case the faultlines re-emerged once it became clear that the Anglo-French intervention exceeded the UN Security Council mandate as understood not only by China and Russia but also by South Africa and Brazil. Whether crisis-driven responses will endure in building long-term cooperation, and add up to something more permanent, extending to the more traditional security dilemmas – such as that between the US and China, China and Japan, China and India, and Russia and West Europe – remains to be seen.

Power South and the Poor South

There is another important question concerning whether, in bridging the traditional North–South divide at the elite level, the new cooperation might create a new division: between the Power South and the Poor South. Here, some historical background may be of interest. The G-20 has a lineage with the historic Asia-Africa Conference held in Bandung, Indonesia, in 1955. Among the G-20 members, six attended that conference: China (People's Republic), India, Indonesia, Japan, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia. From South Africa, then under apartheid, two members of the African National Congress attended as observers. The most conspicuous omission in the G-20 of a Bandung attendee is that of Egypt.

The Bandung conference was influenced by the cold war divisions. Turkey (backed by Thailand and the Philippines) clashed with India (backed by Indonesia and communist China). And two of the G-20 members, the UK and the USA, did their very best to sabotage the conference. The UK worried that Bandung might lead to increased pressure to relinquish its still considerable colonial possessions in Asia and elsewhere. The US feared a propaganda coup by communist China. Acting in concert, the two powers prevented Ghana's Nkrumah from attending Bandung and lobbied and pressured their allies among the Bandung invitees to frustrate not only communist China, but also the “neutralists” like India, Indonesia, and Burma, who were essentially running the show. They even supplied propaganda material (background papers) telling allied nations like Turkey, Thailand, and the Philippines what to say and what do at the conference. Australia made it known that it did not want to be invited to Bandung. Canada was watchful and wary. The Soviet Union overtly supported Bandung but was nervous about China getting too close to Asia with the risk of diluting the Sino-Soviet Bloc (although it did break up soon thereafter, and Bandung might have been one of the reasons). The Bandung conference laid the foundation of the political solidarity of the third world. The latter became a powerful symbol of the global North–South divide.21

Fast forward to the present: just as Bandung was the most talked-about development in the third world in the late 1950s, the most talked-about group featuring in the South today is the G-20. But there are key differences, some with positive implications for the South, others less so.

First, several among the Bandung alumni of the G-20 have themselves changed drastically. South Africa is no longer ruled by the apartheid regime. For Japan, Bandung was the first foray into international diplomacy after defeat in World War II. It has emerged as a key player in Asia and the world. Bandung was communist China's debut on the world diplomatic stage. A poor and fledgling communist country, China then easily invited mistrust. India's Jawaharlal Nehru did his very best (at the cost of his own image and India's influence) to project China as more Asian than communist, partly to wean it away from the Soviet Union. China is now the world's pre-eminent emerging power with a vital role in the global governance architecture. India no longer professes Nehruvian idealism and has gone well past its policy of non-alignment. It no longer wants to unify Asia; that task has long been ceded to ASEAN. Turkey and Indonesia have become more democratic. Indonesia has made a painful but unmistakable transition to democracy, whereas at the time of the Bandung conference it was sliding into authoritarianism.

The South is no longer led by the likes of ideological heavyweights: Nehru, Nasser, Nkrumah, or Mao (represented by the more moderate Zhou Enlai), but by technocrats like India's Manmohan Singh and China's former leader, Hu Jintao. The transition from the firebrand Sukarno to the introverted Susilo Banbang Yudhoyono signifies this shift.

These changes in the South are important factors in shaping the politics of the G-20 and attest to its potential to bridge the North–South divide. Bandung was exclusively a South–South event whereas the G-20 is a North–South forum. Bandung's focus was political, whereas the G-20 is, and is likely to remain, primarily an economic forum, even if it incorporates some political-strategic role.

At the same time, some old North–South divisions remain, and there are now new issues, such as the carbon emission reduction targets and creating a new architecture of financial governance that did not exist in 1955. Key members of the G-20, particularly India and China, stake out positions that are still framed in their predicament and perspective as members of the South. For them, national development goals take priority over complying with the West's demands for greener standards.

It is tempting to view the G-20 as the end of the South and a foundation for global North–South cooperation. But it may also spell the beginnings of a new polarization in international relations. The Bandung conference and its offshoot, the Non-Aligned Movement, were broad and inclusive groupings insofar as the South was concerned. The G-20 is plagued with questions about its level of representation and legitimacy. While some members, such as India, Indonesia, South Africa, Brazil, and China, claim to speak for the South within the G-20, the G-20 itself is seen as an “exclusive club” that further marginalizes the interests and voices of the poorest nations. As one observer points out, “the world's poorest nations are increasingly recognizing that these newly emergent industrial and oil powers no longer speak for them. The international press has also blurred the distinction between developing and emerging economies, making little mention that the G20 nations have become part of the global financial oligarchy in recent years.”22 The G-20 members who are from the South seem keen to leave the rather pejorative label of “third world” behind. They aspire to be leaders of the world, not just of the South. Nations represented at Bandung, including Nehru's India, Mao's China, and Nasser's Egypt, harbored no illusions about achieving global great power status, whether individually or collectively. But today, China, India, Brazil, and Japan all aspire to be global great powers.

The Bandung conference was marred by an open display of differences between the neutralists such as India, Indonesia, Burma, and Ceylon, on the one hand, and the pro-Western camp led by Turkey, Pakistan, Thailand, and the Philippines, on the other hand. There was also the perception at Bandung, albeit exaggerated by Western media, of serious Sino–Indian competition. Today the rivalry between China and India is perceived as more serious and there is additional competition between China and Japan, which was in no position to compete at Bandung. There is the likelihood that competition among the G-20 members could spill over into other parts of the South, like the Sino–Indian competition over African resources and markets, or competition among Russia, China, and Brazil over arms sales to African countries.

The G-20 may also weaken third world regionalism, which has been a building bloc for South–South cooperation. Several members of the G-20, India and China included, do not enjoy the status of spokesperson for their respective regions or sub-regions, and may have less incentive to do so now they have acquired seats on the G-20 table. Unlike South Africa, which claims to consult with the Africa Union on its G-20 role as the sole African member of the grouping, none of the Asian countries are known to consult with their neighbors in shaping the agenda of the G-20. Indonesia, which established considerable regional legitimacy through ASEAN, is now indicating a desire to overstep ASEAN and focus on its G-20 role. In the case of Brazil, a key question is whether its foreign policy should “be focused on improved trading relationships within South America so as to strengthen MERCOSUR, or should Brazil assert its leadership of the G-20 and use that position to ‘reshape the economic order as well as international politics' [as its then president, Lula, put it in New Delhi in June 2007] with a more global projection of its interests?”23 This will not be an easy dilemma to resolve, either for Brazil or the other G-20 nations, especially when regional support is important in fulfilling their global leadership aspirations.

Norm-taking and Norm-making

In the traditional view of norms in international relations, the developing or third world nations are usually seen as norm-takers, rather than as norm-makers. But the third world countries have not just been passive recipients of international norms.24 They have also been active in reinterpreting and giving a more expansive meaning to some of the traditional norms, such as non-intervention and equality of states. Their role has also involved creating new norms for the developing world (or the third world). One leading example here would be the norms of the non-aligned movement, which called for the third world nations to abstain from participation in cold war military alliances led by any of the two superpowers. In recent years, they have also contributed to the development of such norms as “common but differentiated responsibility” in building a global climate change regime. This norm implies that, while both the North and the South have a common stake in protecting the environment, the North bears the primary responsibility for the global environmental crisis and thus should bear a larger part of the costs of environmental protection, including through transfer of resources and technology to the South so that the latter can reduce its dependence on technologies damaging to the environment.25 Moreover, a good deal of their normative role has occurred at the regional level, where institutions have developed distinctive rules and processes of conflict management and cooperation-building.26

Some argue that the emerging powers identify with values “favoring equity and justice for the less powerful and seeking curtailment of unilateral or plurilateral or coalitional activity by the most powerful.”27 It is also clear that the emerging powers remain wedded to the traditional norms of international relations, especially sovereignty and non-intervention, rather than newer principles, such as the Responsibility to Protect (R2P). Hurrell, however, has warned that the emerging power might reinforce some of the bad norms of international relations, including the dangers of economic nationalism and “resource mercantilism.”28

When it comes to global norms, the emerging powers display divergent attitudes, reflecting domestic political conditions and security policies. Part of the reason for their staunch support for non-intervention has to do with the fact that many emerging powers have significant internal conflicts. To mention a few, India's include the Maoist insurgency afflicting its eastern and central provinces (states), and older ongoing conflicts in Northeast India and Kashmir. China's internal challenges include conflicts in Tibet and Xinjiang, and the threat of political unrest, inspired by economic grievances, corruption scandals, and demand for political space against a totalitarian regime. Russia not only has ongoing conflicts in Chechnya, but also has the problem of the “hyper-centralization and personalization of the political system,” as well as “corruption, rent addiction and the dysfunctional relationship between the centre and the Russian regions.” South Africa's challenge is the potential for acute social conflict inspired by the greatest incidence of inequality in the world.29

When it comes to non-intervention, a fundamental norm of sovereignty that has been especially important in the non-Western world, the emerging powers display both similarities and differences. The BRICS countries, despite the differences in their political systems, appear to be somewhat united when it comes to state sovereignty. Brazil has strong pro-sovereignty attitudes similar to China and India. This addiction to Westphalian sovereignty raises questions about the contribution of the emerging powers to global governance, since some of the more pressing challenges to it, such as climate change and global financial volatility, require intervention in domestic affairs. As Hurrell notes, in dealing with “foreign policy and the governance challenges that states face [today] … climate change, stable trade rules, a credible system of global finance – necessarily involves not only cooperation but also rules that involve deep intervention in domestic affairs.”30 Among the emerging powers, China seems to be most interested in introducing new norms drawn from its own history and culture. For example, Yan Xuetong has proposed such principles as “benevolence” and “righteousness” that might complement the extant rules of “equality,” “fairness,” and “justice,” and challenge hegemonic orders (mainly the US-led type) in international relations. For instance, “righteousness” (which he attributes to Mencius) stresses that “one's behavior must be upright, reasonable and necessary.” This he sees as an essential corrective to the formal notion of democracy. “In international politics, democratic procedures may provide legitimacy for actions of a state but not necessarily guarantee the justness of such actions.” Righteousness “requires justice in the contents of state actions.” Here justice means benevolence toward the weak, where there is an imbalance of power. As an example, he asserts that “democracy only gives the right of independent development to weak nations whereas justice requires that developed countries provide assistance to developing ones.”31

Despite their democratic credentials, India, South Africa, and Brazil have made common cause with China and Russia. South Africa, despite having gone through democratization with initial enthusiasm about its promotion, has become noticeably reticent in opposing authoritarian regimes in Africa, partly due to traditional ties between the ruling African National Congress and African leaders like Mugabe and the now deceased Gaddafi, and possibly also because of the ruling ANC party's investments in countries such as Angola and Zimbabwe. Indonesia has adopted a policy of democracy promotion, but it is a soft approach, supporting political change in Burma and establishing a dialogue over democratic ideas and practices through the Bali Democracy Forum.

There have been some recent developments indicating that the normative gap between the established and emerging powers over sovereignty and non-intervention may be narrowing. While China and Russia adopt a much more cautious attitude toward such interventions, South Africa and Nigeria have led the way in turning Africa's staunching non-interventionist stance to one that has allowed a number of collective interventions, including humanitarian interventions. While their dilution of non-intervention should not be overstated, the developing countries, including the emerging powers, are showing signs of being more interested and involved in rule-making, as well as contributing to some of the newer and more progressive norms of world order. The evolution of the R2P is a case in point. It is not well known that many African diplomats and political leaders were not only sympathetic to the R2P idea, but played a role in its development.

The origin of this idea of “responsible sovereignty” is usually credited to Francis Deng,32 a Sudanese diplomat who once worked at the Washington DC-based think tank the Brookings Institution. In a collaborative project, Deng and his colleagues proposed that “those governments that do not fulfill their responsibilities to their people forfeit their sovereignty. In effect, the authors redefine sovereignty as the responsibility to protect the people in a given territory.”33

Well before the R2P acquired a global prominence with the release of the report of the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS) in December 2001, key African leaders in South Africa and Nigeria had advocated collective intervention in response to African humanitarian problems. Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo argued as early as in 1991 that “An urgent aspect of security need is a re-definition of the concept of security and sovereignty … we must ask why does sovereignty seem to confer absolute immunity on any government who (sic) commits genocide and monumental crimes.” And in 1998, South African President Mandela told his fellow leaders: “Africa has a right and a duty to intervene to root out tyranny … we must all accept that we cannot abuse the concept of national sovereignty to deny the rest of the continent the right and duty to intervene when behind those sovereign boundaries, people are being slaughtered to protect tyranny.”34

The ICISS was co-chaired by Mohamed Sahnoun, an Algerian diplomat. Sahnoun himself called the R2P “an African contribution to human rights.”35 The African Union Constitutive Act is the first example of an international organization that has enshrined the R2P into its founding document. It recognizes the “right of the Union to intervene in a Member State pursuant to a decision of the Assembly in respect of grave circumstances, namely war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity.”36 While other regions of the world, notably Asia, have been less receptive to R2P, misgivings about the norms mainly concern its manner of application, including its potential for abuse in the hands of Western powers, rather than the norm itself.

Prospects

A fair assessment of the role of emerging powers suggests that they do face a number of limitations in reshaping global order. The acknowledged members of this club lack sufficient cohesion to make the most of the opportunity presented by the global power shift. At the same time, they carry the risk of creating a new global elitism through clubs such as the BRICS and the G-20, at the expense of those who have provided other types of leadership. Their role in creating new principles of global governance is marred by a continuing emphasis on traditional norms of state sovereignty. Despite their limitations, the emerging powers do challenge the existing inequities in an international order hitherto dominated by the West. They also introduce a healthy diversity of cultural and intellectual traditions to an international system that has previously been derived mostly from the Western political and intellectual traditions (such as the Greco-Roman and the Enlightenment). It is unlikely that they would passively acquiesce with Western dominance of global rule-making and order-building in the twenty-first century, or that they would be co-opted into the existing liberal hegemonic order led by the US, without substantial concessions. At the same time, the emerging powers are not an adequate force by themselves to create a credible alternative. One reason for this is the regional context of their rise, which can either enhance or constrain their global leadership ambitions and potential. That context, alongside the role of regional coalitions and institutions in shaping global order, is a necessary part of the complex equation in thinking about our future as the American World Order ends.

Notes

1 Andrew F. Cooper, “Labels Matter: Interpreting Rising Powers through Acronyms,” in Alan S. Alexandroff and Andrew F. Cooper, eds, Rising States, Rising Institutions (The Center for International Governance Innovation and Brookings Institutions, 2010), p. 76.

2 The EUISS 2030 Report, p. 118.

3 Jim O'Neill, “Building Better Global Economic BRICS,” Global Economics Paper, 66 (Goldman Sachs, November 30, 2001). Available at: <http://www.goldmansachs.com/our-thinking/topics/brics/brics-reports-pdfs/build-better-brics.pdf> (accessed December 21, 2012). Although primarily economic in focus, the report did argue giving the BRICs a greater role in global institutions.

4 “Is This the ‘BRICs Decade’?,” BRICS Monthly, 10/3 (Goldman Sachs) (May 20, 2010); available at: <http://www.goldmansachs.com/our-thinking/topics/brics/brics-reports-pdfs/brics-decade-pdf.pdf> (accessed December 21, 2012).

5 Sharma, Breakout Nations.

6 G-20 members include: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, European Union, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Korea, Turkey, United Kingdom, United States.

7 Cited in Michael A. Glosny, “China and the BRICs: A Real (but Limited) Partnership in a Unipolar World,” available at: <http://guaciara.files.wordpress.com/2010/05/glosny_2009.pdf> (accessed June 7, 2013).

8 A recent initiative is the so-called BRICS Bank, announced at the Durban Summit in 2013. But some see it as a “measure of desperation,” which is “still a long way from becoming a reality”; at: <http://newindianexpress.com/editorials/Reform-the-IMF-to-avert-needless-competition/2013/04/20/article1552634.ece>.

9 Amar Bhattacharya, “Enhancing the G20's Inclusion and Outreach,” in “Shaping the G-20 Agenda in Asia: The 2010 Seoul Summit,” East–West Dialogue, 5 (April 2010): 5; available at: <http://www.eastwestcenter.org/fileadmin/stored/pdfs/dialogue005.pdf> (accessed July 7, 2013).

10 Cited in “Recovery or Relapse: The Role of the G-20 in the Global Economy”; available at: <http://www.brookings.edu/∼/media/Research/Files/Reports/2010/6/18%20g20%20summit/0618_g20_summit.pdf> (Washington, DC, June 2010) (accessed December 21, 2012).

11 Javier Solana, “The Cracks in the G-20,” Project Syndicate, September 8, 2010; available at: <http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/the-cracks-in-the-g-20> (accessed December 21, 2012).

12 David Shorr and Thomas Wright, “The G20 and Global Governance: An Exchange,” Survival, 52/2 (April–May 2010): 181.

13 Bruce Jones, “Making Multilateralism Work: How the G-20 Can Help the United Nations,” Policy Analysis Brief, Muscatine, Iowa: The Stanley Foundation, April 2010.

14 “G-20 Ministers Agree ‘Historic’ Reforms in IMF Governance”; at: <http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/survey/so/2010/new102310a.htm> (accessed December 21, 2012).

15 See: <http://www.globalpolicy.org/component/content/article/185/41128.html>.

16 Jean-Pierre Lehmann, comment, distributed by email by CUTS-TradeForum; see: <cutscitee@gmail.com> (May 10, 2013).

17 Mahani Zainal Abidin, “The G20: Just Another Annual Get-Together of Leaders?,” in “Shaping the G-20 Agenda in Asia,” p. 8.

18 Solana, “The Cracks in the G-20.”

19 Amar Bhattacharya, “Embracing the G20's Inclusion,” in “Shaping the G-20 Agenda in Asia,” p. 6.

20 Andrew F. Cooper, “The G20 as the Global Focus Group: Beyond the Crisis Committee/Steering Committee Framework” (G20 Information Centre, Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto, June 29, 2012).

21 Tan See Seng and Amitav Acharya, eds, Bandung Revisited: The Legacy of the 1955 Asian-African Conference for International Order (Singapore University Press, 2008).

22 James B. Quilligan, “G20 Leaders to Global South: ‘Stimulate This!’ at: <http://www.stwr.org/global-financial-crisis/g20-leaders-to-global-south-stimulate-this.html> (London: Share The World's Resources, July 1, 2009).”

23 New Directions in Brazilian International Relations (Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2007), p. 4; at: <http://www.wilsoncenter.org/topics/pubs/english.brazil.foreignpolicy.pdf> (accessed October 3, 2013).

24 Acharya, “How Ideas Spread: Whose Norms Matter?”; Amitav Acharya, Whose Ideas Matter?; Amitav Acharya, “Norm Subsidiarity and Regional Orders.”

25 Marc Williams, “Re-articulating the Third World Coalition: The Role of the Environmental Agenda,” Third World Quarterly, 14/1 (1993): 20–1. See also Mitsuru Yamamoto, “Redefining the North–South Problem,” Japan Review of International Affairs, 7/2 (fall 1993): 263–81.

26 Acharya and Johnston, Crafting Cooperation.

27 Cooper, “Labels Matter.”

28 Andrew Hurrell, “Brazil: What Kind of Rising State,” in Alexandroff and Cooper, Rising States, Rising Institutions, p. 140.

29 NIC 2030 Report; EUISS 2030 Report.

30 Hurrell, “Brazil: What Kind of Rising State,” p. 140.

31 Yan, “New Values for New International Norms,” pp. 22–3. It should be stressed that some of these principles proposed by Yan are illustrated with explicit reference to the statements of Chinese leaders, and hence appear geared toward justifying China's domestic and external policies.

32 Ramesh Thakur and Thomas G. Weiss, “R2P: From Idea to Norm – and Action?,” Global Responsibility to Protect, 1/1 (2009): 22–53.

33 Amitai Etzioni, “Sovereignty as Responsibility,” Orbis, 50/1 (winter 2006): 71.

34 All quotes taken from Adekeye Adebajo and Chris Landsberg, “The Heirs of Nkrumah: Africa's New Interventionists,” Pugwash Occasional Papers, 2/1 (January 2001); at: <http://www.pugwash.org/reports/rc/como_africa.htm>.

35 Mohamed Sahnoun, “Uphold Continent's Contribution to Human Rights,” July 21, 2009; available at: <http://allafrica.com/stories/200907210549.html?viewall=1> (accessed May 3, 2013).

36 See: <http://www.responsibilitytoprotect.org/files/R2Pcs%20Frequently%20Asked%20Question.pdf>.