CLOSE THE GAP – FOR IMPROVEMENT RECOMMENDATIONS

In business we are often asked to assess and address a gap between desired and actual performance. In these situations it can be tempting to focus only on where we want to go or where we are, rather than tightly linking the two. Our Close the Gap storyline enables you to provide clear and compelling reasoning as to why your plan is the right plan for closing the particular gap in question. It works particularly well when you know what success looks like, or what you need to do to comply with a set of regulations but you are not yet doing so.

To make Close the Gap work for you, you must:

- know that it explains where you are and where you need to get to

- use it to gain your audience’s buy-in in one meeting

- build it to outline a case for your action plan

- stick to storylining rules so your audience supports your action plan.

We will now run through each of these points in more detail.

Understand that Close the Gap explains where you are and where you need to get to

Let’s have a look at the Close the Gap storyline.

Close the Gap pattern

Use Close the Gap to gain your audience’s buy-in in one meeting

You would choose the Close the Gap storyline over Action Jackson when you need to educate your audience about what’s required for success at the same time as providing the action plan. This might be when you need to present a paper to the board, to your leadership, or when you need a fast decision. You might also use it when you need to engage your team in both what needs to be done and why. Here are two examples to illustrate.

Example: entering a new market and due diligence

At the macro level, this storyline is powerful for business cases, legal advice, due diligence reports, audits and more. On the following page is an example.

Close the Gap was powerful when explaining to a US company how to tackle some of the legal aspects of entering the Australian market. If a US company wanted to make an asset purchase in Australia and needed information about three things – the intricacies of Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) rules, how they are positioned in relation to these, and what they need to do to successfully purchase the asset – this would play out as shown overleaf.

America Co storyline

In this example, the legal team used the storyline to structure a letter of advice in a typical legal letter format and followed up with a phone call to work it through with the client and answer any questions. Given the client had expected there would be work for them to do to comply with the ACCC rules, it was a straightforward conversation that explained the rules they needed to comply with and the specific steps they needed to take.

Example: agile meetings

At the micro level this is one of the best ‘stand up’ storylines for the classic agile meeting.

Picture this: it’s 9 am and you’re about to host the stand up on the day’s work. You need to explain to everyone what needs to be done to fix some problems that appeared in the team’s model last week. The story might go like this:

Everyone, finishing Fred’s model is a big priority, but given last week’s distractions he won’t be able to finish it by Friday on his own.

So, we need Mary and Jane to help Fred fix XYZ fields so the model can be delivered by Friday.

Here’s why: for the model to be delivered by Friday, we need to have all XYZ fields complete. But, when we were testing it last night we found three of the fields had corrupted, so we need Mary and Jane to down tools on everything else and help Fred fix these three fields straight away.

Build Close the Gap to outline the case for your action plan

Close the Gap enables you to map out the criteria for success – however you define it – and then match your performance against this before articulating how to move closer towards your desired state.

Your criteria might be set by regulation, or by your own definition of what is required, and that you can persuade your audience is sensible. You then have an opportunity to comment on that in the second part of your structure by explaining how you or your business ranks against that criteria. The last section is, of course, to explain how you will close the gap between the initial criteria and your current state.

Stick to storylining rules so your audience supports your action plan

Here are some problems we often see with this storyline:

- Having an incomplete or poorly organised set of criteria in the ‘statement’. If this set of criteria is incomplete or inaccurate the whole story will fall down.

- Not linking the ‘comment’ tightly to the first statement. If this connection is not tight, your audience will start debating with you and asking questions. They will also be less likely to enable you to get to your third point and support your action plan.

- Not testing that the ‘therefore’ point flows naturally from the first two. It may seem natural to you that your suggestion follows, but this is perhaps not the case for an outsider. We always recommend you ask a colleague to review your logic at a high level before you prepare your more detailed communication.

HOUSTON, WE HAVE A PROBLEM – FOR EXPLAINING HOW TO SOLVE PROBLEMS

When the crew on Apollo 13 uttered those now immortal words, ‘Houston, we’ve had a problem’, they didn’t know they would become etched into the common vernacular. We use the phrase to describe one of the seven great business storylines, with a slight twist – we’re talking about problems we ‘have’ now and what we’re going to do about them.

Houston, We Have a Problem tells the audience about a business problem, its cause, and what steps are required to implement a recommended set of actions. It’s a classic.

To make this pattern work for you, you must:

- understand that Houston is great at combining diagnostics and action

- use Houston when you must convince an audience of a problem and talk them through actions

- understand that Houston maps problems, the cause and resulting steps

- avoid overkill; Houston is about convincing.

Let’s discuss each in turn.

Understand that Houston is great at combining diagnostics and action

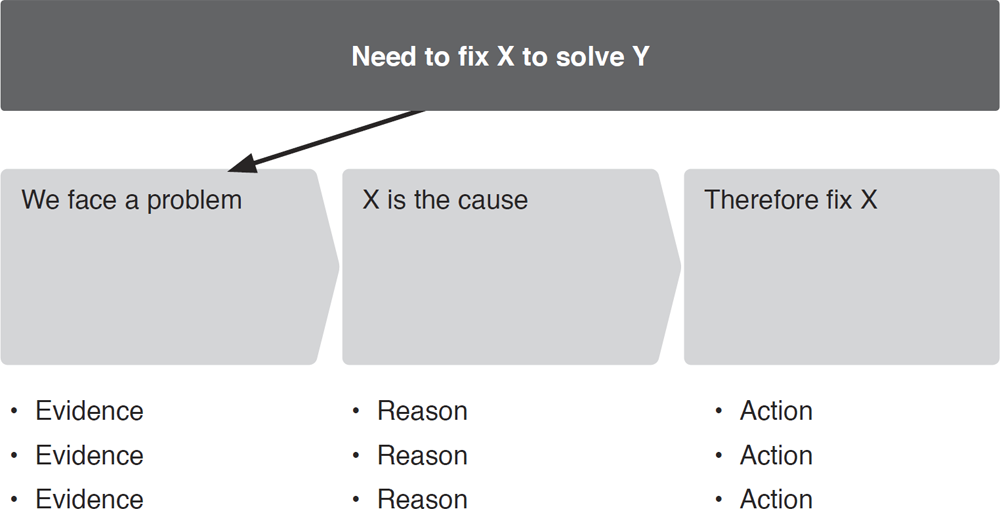

Houston We Have a Problem is a simple deductive storyline.

Houston, We Have a Problem pattern

Use Houston when you must convince an audience of a problem and talk them through actions

Like any deductive storyline, Houston takes the audience through a set of premises that result in one clear recommendation. It’s great for convincing audiences that may be sceptical, or when you only have one opportunity to present both the problem and your recommendations. This might occur with a board or governance committee when you want to provide an update and drive to action in the one meeting.

Here are two examples.

Example: explaining a performance gap

Houston, We Have a Problem helped a finance team we worked with explain a performance gap to a business unit leadership team and outline a set of actions. The storyline is on the following page.

BigBank storyline

You can see that the context and trigger remind the audience of what the communication is about – in this case a regular finance team update to the business unit leadership team. The core of the storyline outlines the performance issue, the looming shortfall and the major causes of that shortfall, as well as the steps required to fix it.

This storyline was used to define the architecture for a PowerPoint pack, which finance used to guide the conversation with the business unit leadership team.

As you can imagine, the pack was not a short one. Although the high-level ideas are simple, they were supported by extensive analysis that the leadership needed to work through. The team was prepared for a robust conversation as presentations about shortfalls and underperformance almost always lead to tough questions, if not a thorough grilling.

The team began their story by explaining the significance of the revenue shortfall, as without an understanding that this was pivotal to bank performance, there was no story to tell. Once there was agreement on this point, the team could then move on to explain what had caused the shortfall.

This again was a tough message to deliver as it painted a difficult picture for some product lines and the teams in charge of them. Those on the leadership team who had responsibility for these areas had been briefed in advance, and even though accepting of the reality and part of the solution described in the third section, they were never going to make the meeting an easy one.

The final leg of the story was easier to present as the bad news had been agreed upon, and everyone was primed for action to correct the problems they knew existed. Importantly, it covered what needed to happen in all four product areas, not just Products A and B, but the storyline does call for a focus on those underperforming products.

Example: a team briefing

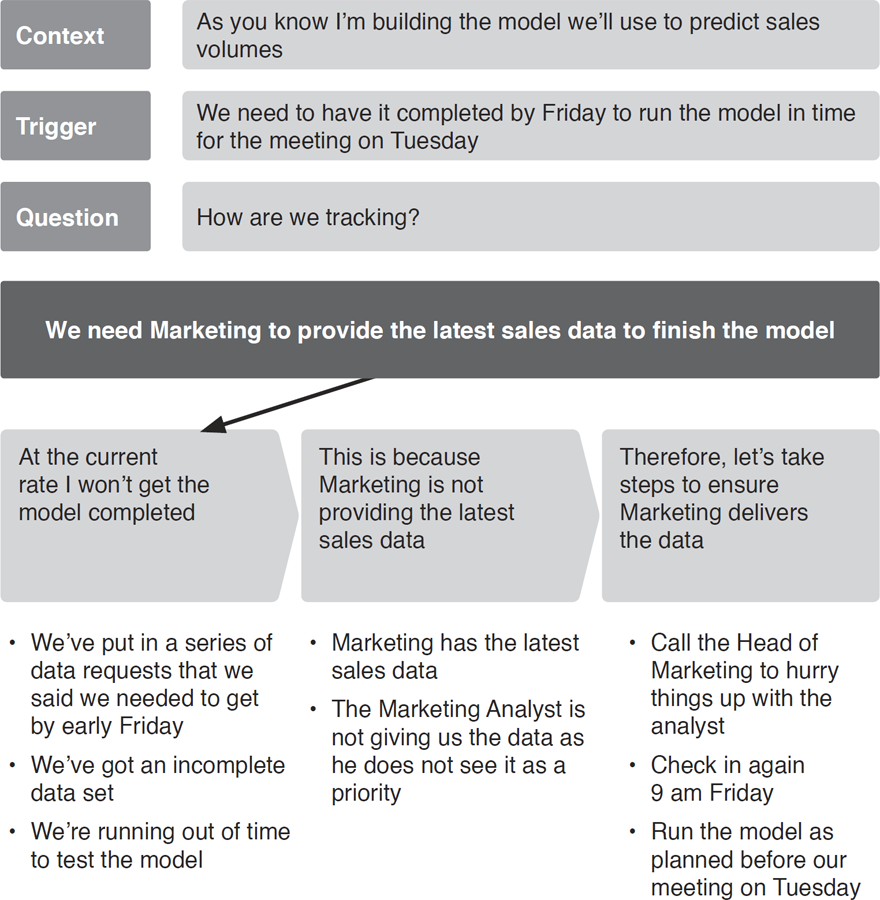

Houston, We Have a Problem is a great storyline structure for the short, sharp team briefing. For example, if a team member wanted to update a project leader on what needed to happen to ensure a piece of analytical work was completed, she might use Houston.

On the following page is an example based on a Houston storyline a client used recently. Given the meeting was informal and short, she used a hand-written sketch of the storyline. Jotting the ideas down helped her collect her thoughts, and the visual structure helped to keep her on point and made it easy to reference.

Marketing model storyline

Understand that Houston maps problems, the cause and resulting steps

Houston outlines the case for action based on a specific cause or set of causes. There are some key elements you must get right if you want to be convincing:

- The ‘So what’ must be a recommendation which also includes the reason why it is the right recommendation. In the example above, it is, ‘We need Marketing to provide the latest sales data to finish the model’. This sentence explains what we need to happen (get Marketing to provide the latest sales data) and why (to finish the model). Either of those points on its own is not sufficient for the ‘So what’ in a Houston story.

- The statement and comment must of course lead to actions – they should remind the audience about what has been agreed, and lead to a ‘how’ question. But, be careful to test that the audience really does need a Houston storyline and does need convincing about why action is needed or why certain steps are required. If they only need a ‘why’ story, The Pitch might be a better alternative (discussed here).

- The statement must highlight that the issue is serious – or at least serious enough to warrant attention. The comment identifies the cause (or sometimes causes) of that problem. It must make the case that this is (or these are) the cause of the problem. Then the recommendation is supported by actions. Be careful to ensure that the actions address the cause or causes outlined in the comment.

Avoid overkill; Houston is about convincing

There are three traps to avoid when using Houston:

- This storyline is about convincing – don’t use it if the audience already knows about the problem and its cause. If they do, taking them through all that again can be boring and frustrating. As a client once said to us when complaining about the information developed by a consulting team, ‘Don’t waste time telling me what I already know!’

- Equally, be careful to avoid this pattern if your audience is the cause of the problem! There are usually many ways to tell a story, and inflaming or embarrassing stakeholders is unlikely to help your cause.

- The other trap is an obvious one: as with all deductive storylines, the problem and the cause must be linked correctly. For Houston to work as a storyline the cause must be ‘the’ cause or set of causes. If it’s just ‘a’ cause then the ‘therefore’ does not follow as the only sensible path to take to solve the core problem you are discussing.

TO B OR NOT TO B – FOR EXPLAINING WHICH OPTION IS BEST

Did Hamlet realise he was describing one of the classic business storylines when he uttered those immortal words, ‘to be or not to be’? Well, probably not. But, in business we are often asked to assess options and make a recommendation.

Too often we see leaders asserting that everyone should follow the option they are recommending, without explaining why it’s the right option. They just say ‘follow me’, which is often ineffective if the audience doesn’t have anything else to go on.

Instead, our classic storyline pattern – To B or Not to B – takes the audience on the journey through the thinking that makes the case for your preferred option.

To make this pattern work for you, you must:

- know that To B or Not to B argues for one particular option

- use To B or Not to B to take your audience on the journey through your thinking

- understand that To B or Not to B enables you to explain first, recommend last

- make sure it’s complete – this story is great when you need to work through all the options, not just one option that you like.

Let’s consider each of these.

Understand that To B or Not to B argues for one particular option

To B or Not to B is a simple ‘options’ story that we see used often. It’s great for explaining a problem to an audience, taking them through the options (A, B and C), explaining why your preferred option (B) is best, and what needs to happen to implement your preferred option.

To B or Not to B pattern

Use To B or Not to B to take your audience on the journey through your thinking

Choose the To B or Not to B storyline when you need to educate your audience about why action is needed, what options are on the table, and the action plan they will need to implement. This might be when you need to present a paper to a senior team or a board when they need to understand what needs to be done and why. Equally, it might help engage your team when they need to put your recommendation into action.

Like all our storyline patterns, we see this being useful in multiple situations.

Example: the business case

This is powerful when recommending a course of action. To B or Not to B is a great business case structure when you must convince your audience of the best option and a course of action in just one conversation. An IT team used this storyline pattern to convince the Chief Operating Officer (COO) to invest in a technology service provider’s solution to a data management problem. The storyline had to be tight and clear: the IT team had failed to win support for other projects as they had confused the COO with too much technical detail.

Here’s how they used To B or Not to B to engage the COO this time, using the storyline to frame the architecture of a PowerPoint pack.

Coonawarra Corp storyline

You can see that there is a ‘given’ established in the CTQ that needed no justification or explanation with the COO: intelligent cloud-based data management is critical. Also, the team wanted to let the COO know they had been digging into the issue. Their recommendation was clear: go with ‘Black’.

The underpinning logic of the storyline enabled the team to take the COO on the journey quickly:

- The first statement described the options that the team had analysed: there were three potential organisations they could engage going forward – ‘Black’, ‘Yellow’ and ‘Pink’ – and they needed to describe each one at the start.

- The second section evaluated the options: it was important to put up all the options to be considered. Each option was analysed against the same criteria – cost, budget, technical solution offered, and so on – and ‘Black’ emerged as a clear winner.

- The final section outlined the action plan at a high level, and was only discussed once the COO was on board with the idea that there was a problem to solve and that going with Black was the right way to do it.

The result? They got the decision they wanted, and the COO told the team that if they presented business cases like that in the future he’d approve everything – fast!

Example: outsource or insource?

To B or Not to B is powerful when explaining what courses of action someone should take when confronted with an underperforming vendor.

In this example a manager was concerned about the performance of a vendor and wanted to recommend bringing the service in house. He developed a simple To B or Not to B storyline and presented it in a Steering Committee meeting.

The storyline is deceptively simple and high level, and was used to guide the conversation. The manager rightly expected to be grilled on the details and to receive thorough and specific questions about the problems with the ServCo arrangement and the risks of bringing the project in house.

One of the Steering Committee members had their reputation at stake given they had recommended going with ServCo. Even though the team had kept this person across the problems as they emerged, this person had some tough questions. However, the team was ready, and provided enough evidence that the leadership as a whole agreed the service should be brought in house.

Here’s the storyline they used.

Bondi Compliance storyline

Understand that To B or Not to B enables you to explain first, recommend last

So, how does it work? To B or Not to B maps options, and recommends a course of action. There are some key elements you must get right:

- The introduction must set up the story that’s coming. But, be careful not to introduce material that will require justification – that should be in the main part of the storyline, not in the introduction.

- The ‘So what’ must be a recommendation that also explains why your solution should be adopted. In this type of story the ‘So what’ synthesises the whole story, but – as in all deductive storylines – rests heavily on the ‘therefore’ point. That is, after all, the point of the story – is it B or not B? Make sure you don’t fall into the trap of just stating, ‘There are three options’.

- The logic must work. The ‘statement’ must outline the options available. The ‘comment’ lays out the reasons why one of the options – B – is best, which leads to the ‘therefore’ point, which explains to the audience what steps are required. The key is to ensure – as with all deductive storylines – that the statement and comment are ‘true’, and that the comment really does comment on the statement.

- It needs to be right for your audience. To B or Not to B works well when you have only one shot at communicating with your audience and you need to take them on the journey. Only use it if they don’t already know the details surrounding the problem. Otherwise you’ll just annoy them telling them things they already know.

Make sure the options are complete

There is an obvious trap to avoid here. The problem and options must be linked, with the problem also being serious enough to warrant action. The audience must agree with you that the problem is worth solving before you take them to the next phase, where you explain the options you see for solving that problem.

You must also present a complete, mutually exclusive set of options. That’s where the audience’s mind will go once they agree that there’s a problem worth solving.

In the example described above the problem could be dealt with internally or with outside assistance. So, it was critical that both options were analysed thoroughly or the audience would not necessarily agree that bringing the project in house was the best option.

WATCH OUT – TO COUNTER EMERGING RISKS

We’ve all heard it before: ‘Yes, that’s okay, but … ’ Well, this is the basis of one of our classic business storylines. We call it Watch Out for a reason: it’s a warning storyline that tells your audience there are risks ahead that must be managed. Like Houston, it’s not just about the warning, it drives the audience to the steps required to address the risks ahead.

To make this pattern work for you, you must:

- know that Watch Out combines what’s working, risks and action in the same story

- use Watch Out to persuade your audience on the need to change direction

- know that Watch Out maps what’s succeeded, the risks and their remedies

- avoid crafting a narrative that flows without compelling logic.

Let’s discuss each of these.

Understand that Watch Out combines what’s working, risks and action in the same story

Watch Out is a simple deductive storyline. It makes the argument that action is required to address risks that are important enough to warrant attention.

Watch Out pattern

Use Watch Out to persuade your audience on the need to change direction

Like any deductive storyline, Watch Out takes the audience through a set of premises that results in one clear recommendation – the ‘therefore’. It’s great for convincing audiences that action is required or where you only have one opportunity to communicate with the decision makers – such as with a board or governance committee where you want to provide an update and drive to action. The difference with this storyline is that it’s all about risks and managing them.

Example: the ‘uh-oh’ moment

Watch Out helped a project leader make the case for action with a Steering Committee. Here’s the storyline.

The BigCo Risks storyline

This was just one of many projects reporting that day. As a result, the context and trigger remind the Steering Committee of what the project is about and the issues they looked at last time. Importantly, the question is all about what the Steering Committee must do. The ‘So what’ for the storyline highlights the actions that the project leader wants the Steering Committee to take.

The supporting logic is deductive, as we’ve said. It outlines the big wins the project has had in the ‘statement’. Importantly, in the ‘comment’ the point is made that risks are emerging that must be addressed. Without this imperative, these might be any old risks. Then the ‘therefore’ follows – let’s address those risks.

Watch Out, like many others, is also a great storyline structure for the short, sharp team briefing.

Example: the leadership team ‘heads up’ update

Watch Out helped a team member provide a ‘heads up’ update for the leadership team. Typically, she would have used a pack of spreadsheets to provide a numbers-based update. Instead, she took what was for her a big risk – she spoke about the update, using the storyline to guide the conversation.

The storyline is on the following page.

Here are some subtleties to note about this storyline that made it work:

- The context and trigger reminded the leadership gently about the objectives of the strategy – they have bold aspirations.

- Importantly, the question is focused on ‘action’, not just an update.

- The structure of the storyline was also important. The deductive structure allowed her to tell them about FY17 wins, drill into the FY18 concerns (that were definitely serious enough to warrant action), and then focus on some key actions that she wanted to recommend (gently) to the leadership team.

Once she finished her update she received a round of applause from the leadership team!

The Heads Up storyline

Understand that Watch Out maps what’s succeeded, the risks and the remedies

There are some key elements of the storyline you must get right:

- The CTQ must lead to a question about action (as with the questions in all deductive storylines).

- The ‘So what’ must be a recommendation for action that also includes why that recommendation is the right one. It may be a recommendation such as: ‘We should do X to achieve Y.’

- Each major part of the storyline must do its job – in this example the ‘statement’ describes what’s been working, the ‘comment’ describes the risks that must be managed for the overall task to be a success, and the ‘therefore’ point outlines the actions required to address the risks and keep the project on track.

Avoid crafting a narrative that flows without compelling logic

Don’t fall into the trap of just laying out what’s working, what’s not, and actions. A flow of ideas that simply relate to the same topic is not sufficiently compelling to encourage your audience to agree with the actions recommended. The logic must compel the audience to act on your specific recommendation.

The comment is key. In the earlier Project Big example it was clear that if the risks were not managed then the go-to-market timetable would not be met, which was a completely unacceptable outcome. So, action was necessary, not just ‘nice to have’.

* * * * *

So, now you’ve seen seven of our classic storyline patterns. Now we want to shift gear – to look at how you use a storyline to shape the communication you share.