No one visited the ballroom that night. I kept watch, peering through the keyhole of the library door (the two rooms were opposite each other). As the hours ticked by, I took a risk and decided to enter the grand chamber myself, hoping to discover that elusive hidden door. I was relieved to find the ballroom unlocked—how wondrously convenient! I searched the vast chamber, without success, until I heard the servants waking up and moving about the house. Defeated, I returned to my bedroom chamber for a few hours’ sleep.

Bertha woke me in a great state of excitement. The ball was that very night, and the house was teeming with activity. I sat before the dressing table, listening to her babble about all the details, as I carefully put on my face.

“I sneaked a peek at the ballroom,” she said eagerly, picking up my wig and running a brush through it. “And what a sight! I’ve never seen such splendor. Though the kitchen’s in an awful panic—the cheese never arrived, and they’ve had to send for another lot.”

A note had come by the early morning post. It was from Mr. Partridge. He asked how I was enjoying Butterfield Park and reported that as yet he had been unable to locate Anastasia’s missing child. He wondered if perhaps McCloud had put the infant into an orphanage—and said that he would start making enquiries. But that was unlikely. Hadn’t Baron Dumbleby told me that McCloud had always wanted a child of her own? Why then would she give it up?

“Miss Estelle was up early this morning, taking a stroll,” said Bertha. “She gave me such a look. She hates me, she does.”

The poor lump had followed Estelle for much of yesterday, but had come back with nothing of interest to report, apart from the fact that the awful girl spent much of the day lazing about the conservatory. I twisted my braid into a tight bun and pinned it. “I wouldn’t worry, dear. Estelle has more on her devious mind than you.”

“She has a black heart.” Bertha slipped the wig over my hair and made a few adjustments. “There, miss, all done.”

Esmeralda Cabbage looked back at me in the mirror. But for once my reflection didn’t fill me with hope. For the day of the ball was here. I had been thoroughly convinced I would find Anastasia within hours of reaching Butterfield Park. But I had failed. Nor was I completely certain about my ingenious plan to reach Rebecca. Time was fast running out.

“What’s wrong, miss?” said Bertha uneasily. “You look awful serious.”

I stood up. Paced around the room like a prisoner awaiting sentence. “Bertha, I need you to listen to me very carefully.”

The maid sat down on the bed and gulped. “Yes, miss?”

“If we do not find Anastasia by the end of the ball tonight, I fear we never will.” I stopped in front of the quivering maid. “But if we do find her, and we must, it’s very important that you follow my instructions.”

“But why must it be tonight? We are to stay on at Butterfield Park for another two days.”

“I will not be here beyond tonight,” I said. “At least, I hope not.”

Bertha jumped like a startled bunny. “What do you mean, miss?”

“Only this. I have a plan that I hope will take me to Prospa without the stone’s help. Tonight is the only night it can happen.”

“I don’t understand,” said Bertha, beginning to sob.

“Bertha, listen to me,” I said gently. “I must go to help a friend who needs me even more than Anastasia.”

“You mean Rebecca?”

I nodded, my thoughts flying to the mysterious veiled figure I had seen looking at Butterfield Park from the woodlands. “I have a plan. As yet the pieces are not in place, but I have high hopes.” I reached into my pocket and pulled out an envelope, handing it to Bertha. “There is money inside and an address in Weymouth. When I find the secret door, we must get Anastasia away from this house—tonight. Take her to that address. Take her there and keep her safe.”

Bertha’s hands were trembling as she took the envelope. “Isn’t Weymouth the very place you ran away from?”

“That’s right. It is the very same cottage by the sea.”

I could see the fear blooming in Bertha’s eyes. “And didn’t you say Miss Always went to that house looking for you—and that she took your friend Jago as her hostage?”

“Yes.”

“What if Miss Always comes back?” she cried. “You said she’s awful dangerous.”

“Miss Always wouldn’t think I’d be stupid enough to go back to Weymouth.” I smiled triumphantly. “She doesn’t know me at all. So, will you do as I have asked?”

“I will,” said Bertha, hugging her arms. “But I’m awful scared, miss.”

“Stuff and nonsense,” I replied brightly.

Though I couldn’t deny the shiver creeping through my bones.

Esmeralda Cabbage wore a peach-colored dress made of silk. Her flaxen hair hung loose around her shoulders, fixed with an auburn ribbon. And her face, held in place by a little glue, had the noble glow of a piglet. She would fit right in among three hundred aristocrats.

The ballroom was as glorious as Bertha had described. The vast room glowed like a jewel beneath the eight chandeliers, each one flickering with a hundred candles. The windows were now covered by the red velvet curtain, which shimmered in the soft light. As I entered the room, the orchestra was playing a waltz, and already a great many guests were dancing about. There were lords and ladies as far as the eye could see. With dukes in tails and top hats and duchesses sparkling with embroidered gowns of brocade silk, feathered hats of every shape and size, and frills and flounces everywhere you looked.

Servants milled about in starched uniforms, filling empty glasses, pulling out chairs, and anticipating the guests’ every whim. The banqueting table was a triumph, running down the middle of the ballroom—it was decorated with fresh orchids and candelabras and laden with silver trays teeming with sweetmeats and potatoes, fish, crab and lobster, and every kind of game. There were puddings and tarts and cakes in a rainbow of colors. And the centerpiece of the table was an enormous red-and-blue jelly at least ten feet long—a wonderfully wobbly replica of Butterfield House itself, with the words ONE HUNDRED YEARS carved into the top.

I ventured over to the windows, parted the curtains, and took a peek outside. And noted with a rush of excitement the half-moon etched into the sky, throwing pale light over the park.

“You look lovely, Esmeralda.”

It was Lady Amelia. She looked like a pound of butter squeezed into a sparkling red sock. “Thank you, Lady Amelia. So do you.”

She giggled. Then took a large gulp of her wine. “I’ve never seen the house so full—Lady Elizabeth will be most pleased.”

“I can’t think why,” snapped Matilda. “It’s utterly boring, that’s what it is.”

Across the ballroom I saw Estelle Dumbleby make her grand entrance. She didn’t look even slightly wicked in a blue-and-white dress, a stunning ruby necklace at her throat. She immediately caught the eye of Lady Elizabeth, who was standing beside Countess Carbunkle (who wore a hat positively bursting with peacock feathers). The three of them huddled together and talked for some time.

It was an astonishing coincidence to see them all gathered under one roof. Thank heavens for my brilliant disguise and my staggering acting skills. Here I was, right under their noses, and those clueless chumps didn’t suspect a thing.

“Who on earth is that?” said Matilda, pointing rudely.

I looked over and saw the object of her disapproval. A woman had entered the ballroom. She wore a long black dress, black gloves, and a small hat, and a veil covered her face.

“It’s probably Mrs. Winterbottom from the village,” said Lady Amelia. “Her husband died in a shooting accident last spring, and she is still in deep mourning.” Lady Amelia sighed. “Poor woman. Her suffering must be hard to bear.”

“Who’s suffering?” Lady Elizabeth had joined our little group.

“Mrs. Winterbottom,” said Lady Amelia. “She is in grief.”

The old bat squinted and cocked her ear. “Mrs. Winterbottom’s in Greece? I saw the blasted woman at church yesterday morning!”

Matilda laughed heartily.

“I’m surrounded by idiots.” Lady Elizabeth huffed.

I peeled away from the group and walked about the ballroom. Stomping on the floor. Pushing on the mirrored panels. All very discreetly, of course. The wall behind the orchestra was rock solid, so there was no possibility of a hidden door. Which only left the wall of mirrors. The secret door had to be there.

“What are you doing, Esmeralda?”

Estelle had slithered up beside me as I was examining a panel of mirror.

“Just admiring the craftsmanship,” I said casually. “They don’t build houses like this anymore, what with the empire crumbling and whatnot—I blame the poor, don’t you?”

“I rather thought you were looking for something,” said Estelle sweetly. “You seem terribly preoccupied by these mirrors.”

“Well, I’m rather fond of my own reflection,” I said, glancing at Estelle through the glass. “Though I find it strange, what with so much to see and do at this great ball, that you choose to spend your time watching me.”

Estelle blushed and giggled. “I confess I have a rather curious nature—do you think it terribly vulgar of me to wonder about what people are really up to?”

“I’m sure you’ve done worse,” I said brightly.

The smile slipped from her face. She turned on her heels and swanned away.

There was a foul smell wafting about the ballroom, and it was hard to miss.

Countess Carbunkle certainly hadn’t missed it. She stood by the banqueting table, munching with great enthusiasm on a lobster claw, her peacock feathers fluttering about as she spoke. “What on earth is that odor?”

“Countess Carbunkle,” I said, with a wave of my upper-class hand, “what you smell is the stench of moldy aristocrats—gout, mothballs, a fondness for horses and whatnot. My grandmother stinks to high heaven, and she is first cousin to the King of Spain.”

“Is she indeed?” said the Countess with an arched eyebrow. “Who is this grandmother of yours?”

“Lady Ophelia Cabbage,” I said grandly. “A very great woman. She was the toast of London before she set sail for India.”

“I very much doubt that.” The Countess smeared some buttery cheese on the lobster and took another hearty bite. “Why have I never heard of her?”

“It is a great mystery,” I said. “Grandmother was a terrific snob. As a chinless countess with bad manners and appalling teeth, you would have been just her cup of tea.”

For some reason, this caused Countess Carbunkle to cough suddenly—sending a piece of lobster shooting across the room, where it landed in the hair of a baroness from Gloucester. Just at that moment, the lady in the black veil passed by. Countess Carbunkle took an instant dislike to her. “Probably that wretched Miss Anonymous,” she grumbled, pointing with her lobster claw. “It would be just like her to slink about looking for gossip to put in that beastly column of hers. I would gladly tear her limb from limb.” Then she laughed unconvincingly. “Just a little joke.”

I felt the moment was right to tell the Countess she had a chunk of lobster hanging from her chin hair. Countess Carbunkle gasped, blushing furiously. “I do?”

“Yes, dear. If it were any longer, you could lower it into the river and catch a salmon.”

The Countess grabbed a napkin and wiped her chin, and in doing so smeared the buttered lobster claw across her gray dress. That made her gasp again. “Just look at the stain,” she cried. “How beastly! How humiliating!”

“Nonsense,” I said, feeling rather sorry for the silly creature. “I can remove that in a flash.”

I grabbed the napkin from her hand and dipped it in a glass of champagne. Then dunked it in a bowl of cranberry sauce.

“What are you doing?” said Countess Carbunkle, beginning to back up.

“Saving the day,” I said with a winning smile. “This mixture will take that stain out in no time. For best results, I usually require a spoonful of crushed beetle wings, but there isn’t time.”

“This dress cost me a fortune!” she shrieked.

“Well, that’s not your fault, dear,” I said, attacking the stain with gusto. “I’m sure it looked perfectly lovely on the mannequin.”

The Countess backed up toward the banqueting table in an effort to escape my reach. Though why, I couldn’t say. “Get off me!” she snapped.

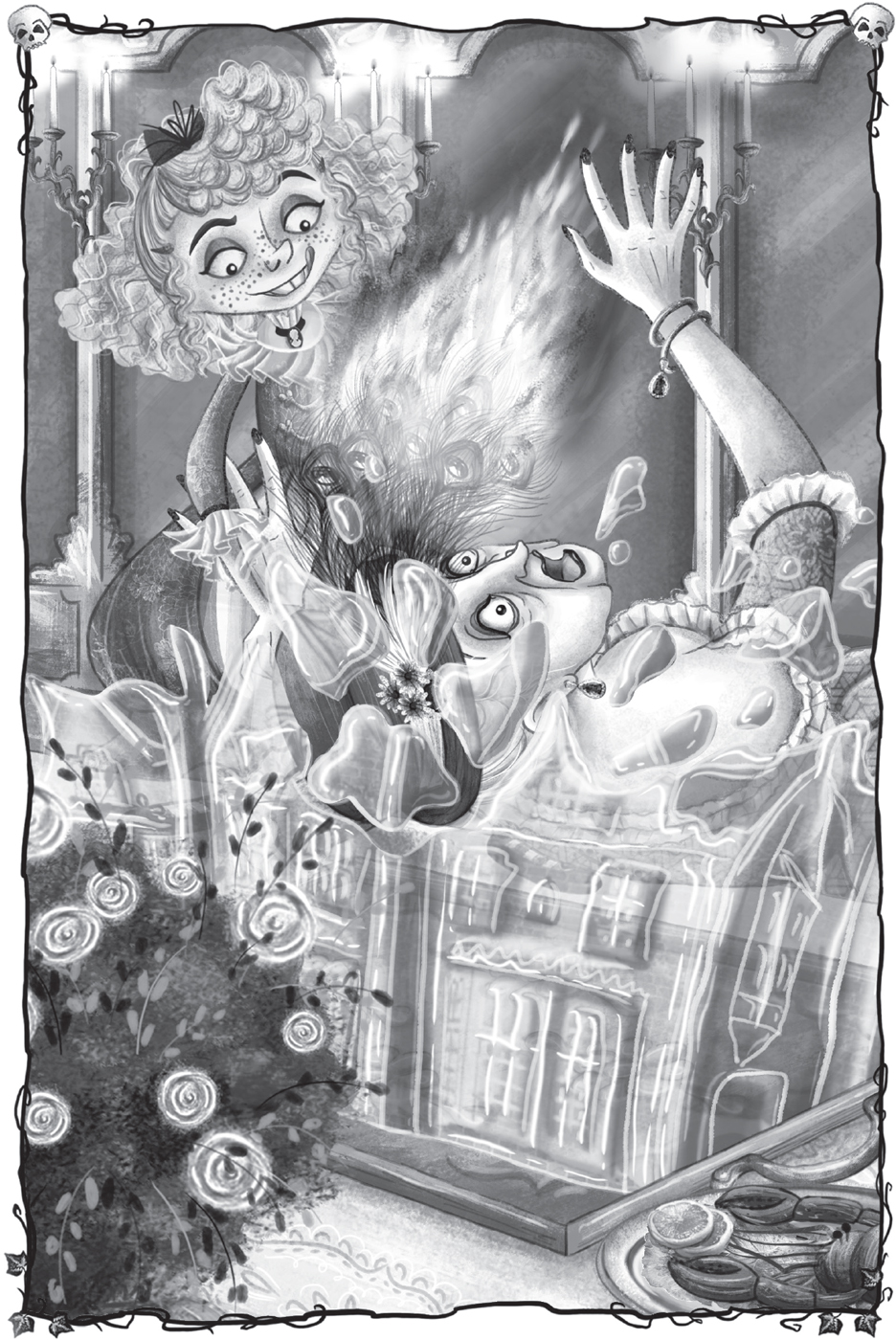

At that point, things took a turn for the worse. For some strange reason, Countess Carbunkle did not want my help. In fact, she seemed to view it as a form of sabotage! Which is why she was pulling away, her buttocks pressed against the table, her back arched. Which is also why the enormous peacock feathers sprouting out of her hat made contact with a flickering candelabra. And caught fire. The flames roared to life and spread across her feathers like a forest fire. Within seconds her entire hat was burning up.

A pair of dames standing nearby began to shriek.

Countess Carbunkle sniffed the air. “What on earth is burning?”

“You are, dear,” I said.

The Countess straightened up and caught sight of herself in the mirrored panels. Which is when she began to scream like a woman whose hat was on fire.

Naturally I was happy to assist. By then the fire was spreading rapidly toward her hair. So I had to act quickly. I looked around for a suitable method of quelling the flames. And found it the moment my eyes flew to the banqueting table. “Brace yourself, Countess Carbunkle!”

“What for?” she shrieked.

Rushing at her like a bull, I pushed hard on the Countess’s shoulders, sending her flying back onto the table. Her landing wasn’t especially elegant; gravy boats and pheasant went hurtling into the air. Then I leaped onto the table top and slammed her head into the centerpiece—and her hat, indeed her entire head, splattered into the gigantic red-and-blue jelly of Butterfield Park.

The delicious dessert smothered the flaming hat. As Countess Carbunkle’s head sank deeper into the jelly, it squished around the sides of her face and spluttered over the top of her dress and up her neck. It had worked a treat! The entire ballroom fell silent. Even the orchestra stopped playing.

“You . . . you . . . stupid girl!” thundered Countess Carbunkle.

“Help her, you fools!” barked Lady Elizabeth, directing two gawking footmen toward Countess Carbunkle. They hurried over and pulled the Countess off the table. Great chunks of jelly were stuck to her hat and the sides of her face. But she arranged herself with great dignity. Head high. Jelly falling from her ears. There was a small amount of sobbing. And some rather unkind accusations.

“There is a jug of water!” she bellowed at me. “Could you not have thrown the water at my hat instead of pushing me into the centerpiece?”

“Now there’s a thought,” I replied. “Countess, you looked awfully rattled. Perhaps you’d be more comfortable lying back on the banqueting table with the other desserts?”

The Countess responded by grabbing a baked potato and throwing it at my head. I dropped down just in time. The potato sailed over me and hit a violinist in the nose. He went flying back—and as he did, he reached for anything to halt his fall. The closest thing was a candelabra mounted on the wall. So he grabbed it.

But no one was paying the violinist any attention. It seemed the whole ballroom had gathered around Countess Carbunkle, trying to sooth her distress. But while the guests and the waiters fussed over a jelly-covered aristocrat, I had my sights set on the violinist. It seemed that only I had noticed the candelabra bend when he grabbed it, then snap back into place as he fell to the floor. Bend and snap back. Rather like a handle. And that right after, the mirrored panel closest to the orchestra had popped open—just a crack. To the untrained eye, it might seem like nothing at all. But I knew exactly what it meant.

“The door,” I whispered.