At one time the whole of Ireland must have been half full of holy men and women. Throughout County Clare there are wells dedicated to these saints, and here and there they have left their mark on the landscape. In some places it is literally footprints, while in others it may be the imprint of their knees in prayer, an austere stone pillow, or a row of stones on a hillside where they have cursed thieves and turned them to stone.

Here’s a wee story of three saints in search of a place to settle. It is just possible that they invented surfing, something that is very popular on Clare’s beaches nowadays.

Maire loved the sea. She loved the sound of the soft waves, shushing onto the pebbles of the shore. She loved the breeze and the smells it carried to her. She loved the song of the birds as they wheeled above her or came to land, bobbing on the waves. She did not usually mind her mother sending her to gather seaweed from the shore at Ross. It gave her the freedom to cast off her stockings and shoes, put down her basket, and dance along the sand, for there was no one there to see her. So long as she returned with a full basket, no one would care that she danced with a heart free and light as a spirit of the waves, or sang with the birds on the rocks.

This day, as she was crossing the green field, she saw there were three holy brothers working on the shore. Maire knew them by the way they wore their hair and their long robes. While they were busy at their task, she took off her stockings and shoes and laid them on a rock. She lifted up the bottom of her skirts to keep them from getting wet. She moved along the line of the shore with the grace of a dancer. As she was skimming flat stones into the water and laughing as they bounced on the waves, one of the brothers turned to watch her, and he said, ‘Hasn’t that girl just got the loveliest little white feet?’

The other two men turned to look, then quickly turned back, telling the first brother that he had sinned. Firstly for watching the girl at all; then for noticing her bare feet; and worst of all, for passing a remark that drew their attention to the girl’s bare feet and caused them to commit a sin too!

The holy brothers decided they must pit themselves against the elements in penance for their sins. It was the habit of holy men and women in those days to take themselves away from the temptations of the world and to live in caves or sleep in rocky beds on remote islands. It seemed that the shore of Ross was not remote enough to save them from temptations of the flesh.

Maire watched as the first brother sought out a large flat stone and, taking it to the water’s edge, he stepped upon it. Balancing on his flagstone on the waves, he raised his arms and said a prayer, trusting that the tide would carry him wherever God wished him to go. The other two brothers followed his example on flags of their own.

The three sailed down around Loop Head and into the mouth of the Shannon. The first came in to land at Kiltrelice, and where he stepped ashore a well sprung up. Today it is named after him, St Cuan. The second brother, St Creadaun, landed at Carrigaholt, and a well arose there; while the third brother, whose name was St Cronan, came ashore a few miles along at Kilcronan, where a well still bears his name.

![]()

St Colmkille is famous for copying a book that caused a huge upset, led to a great battle and the saint being exiled from Ireland. Colmkille sailed across the sea to Iona, where he built his church and started converting the Scots. None of those things happened in County Clare. What he did here was leave the mark of his boot-nails on a rock.

On Mount Callan there was a place where people used to gather to celebrate the festival of Lughnasadh, marking the beginning of harvest time. Now I don’t know whether it was that time of year, but anyway, St Colmkille was travelling from Galway to Mount Callan one time, and he had a dog with him for company. As they got near to Mount Callan, a hare leapt up out of the grass and the dog chased it, with the saint running for all he was worth to keep up at his heels. The saint and his hound chased the hare to Cluain Caolan, where it went out onto the peninsula. The hare took a great leap across the breadth of the lake, which was no mean feat as the lake was 300 yards wide at that point. The hound and the saint followed where the hare had leapt, and there are marks still on a large stone where they landed. Now I do not know if they caught the hare, but there are three sets of prints on that stone: the tracks of the hare, the dog’s paws and the mark of the iron nails of St Colmkille’s boots.

![]()

In the time of the saints, there were three holy men who lived together in a cave in the parish of Ballycorrick, just north of Clondegad Bridge. Their names were St Scriobhan, St Nuadan and St Ruadh. It seems that even the best of us cannot be at peace with our fellows at all times. One day, the three saints had a serious difference of opinion on some ecclesiastical matter. Although they could find no common ground on the matter, they could at least agree that they must go their separate ways. St Scriobhan would remain at Clondegad, as he had been there long before the others had settled. Scriobhan’s spartan bed is still there in a narrow recess beneath an overhanging rock at the top of the waterfall in the Clondegad River. The other two would travel abroad in search of some new stretch of wilderness in which to speak to God. As the judgements of men had proved lacking, they let a higher power decide the matter of where they should go. The two each made a gad of rushes and threw them out into the river, planning to travel in whatever direction their gad took. Nuadan’s gad went against the current, so he travelled up-river, and settled at the place now called Tubbernuadan, or Nuadan’s Well. Ruadh’s gad went with the river and he travelled southwards, settling near Ballynacally. Since then the parish has been called Clondegad, or the meadow of the two gads.

![]()

St Mochulla of Tulla kept a tame bull that he had trained to carry messages for him. At this time, the saint was busy building his church on the hill at Tulla. He was so engrossed in his work that he had no time to stop to get provisions or cook his dinner. So, he made an arrangement with the monks in Ennis. They would cook him some dinner when they were making their own, and St Mochulla’s blessed bull would collect it. He would fasten a bag around the bull’s shoulders and send it off to Ennis. The bull knew the way and would walk there and back quite happily, serving his master. There would, on occasion, be more than food in the bag the bull carried from Ennis to Tulla. Whatever the saint needed would be sent this way: perhaps holy books or relics, or maybe even gold.

A gang of seven thieves got to hear about the clever bull and planned to rob the beast. It was not so much the bull itself, as what he might be carrying that they were after. They knew the route the bull was used to travelling and hid themselves on Classagh Hill, ready to waylay him on his return from Ennis. As the bull approached, the thieves leapt upon him, beating him with sticks and emptying the bags. The bull gave one almighty roar, so loud that he could be heard in Tulla. St Mochulla laid down his tools when he heard the terrible call. ‘Who dares to harm my good servant?’ he cried. He prayed for the safety of the bull and cursed the men that dared to hurt him.

Right then the men on the distant hill froze as they were, suddenly turned to stone. Perhaps one or two of the robbers escaped the curse, for today there are only four stones standing in a row on the hill. The place is known as Knocknafearbreaga, which means the ‘hill of the false men’.

For all that Clare is a large and extensive county, it is the one county that St Patrick never set foot in. The closest he came was to near Foynes in County Limerick. Many people from West Clare, came to hear him speak, it being simple enough to cross the Shannon by boat. He spoke to them directly, telling them that a child born in Corca Bascin would do for Clare what he, Patrick, had done for the rest of Ireland.

At that time, in some places the older faith lived side by side with the new. Many druids recognised in the Christ that the saints spoke of, a master of the elements, a great druid.

On the hill of Ballyvaskin there are huge stone walls where the princes of Corca Bascin lived from before the birth of Christ until the Battle of Clontarf. Here lies the Grianan, a triangular section of ground that would have been a sheltered, sunny spot, where members of the court could take their ease. It was here that the chief held his annual feast and assembly for the people of West Clare. He did this once a year, and guests came from every part of West Clare, rich and poor among them. The prince sat in his grand chair, and his druid sat by his side, in a place of honour as his wise counsellor. The druid paid no heed to all the assembled people, until a couple, obviously very poor, entered. The druid stood up, bowed and invited them to please take his chair. The prince was puzzled and asked why the pair had been chosen. The druid spoke loudly and clearly so the whole assembly could hear: ‘In this woman’s womb, there is a child who will bring the Christ’s message to the people of Corca Bascin. He will do many miracles and baptise the people.’ And the druid foretold the coming of St Senan.

The woman’s name was Congella. She was walking through a wood when her birth pangs began. When she grasped a bare branch of a tree it burst into bloom at her touch. A flat stone still marks the spot where she gave birth to her son in Moylough, near Kilrush. Even as a very young child he showed some miraculous qualities. He spoke his first words early, and seeming older than his years, his mother called him Senan, meaning ‘old’.

Senan’s father had a farm about 3 or 4 miles from Kilrush. The land was separated from the mainland by Poulmacsherry Bay. He kept a herd of cattle there. One day, his father told Senan to drive the cattle to the farm alone, as he had no time to do it. Senan obeyed his father’s command and drove the cattle. When he reached the shores of the Bay he did not know how he would drive the cattle across the water with no one there to help him. Senan went down to the water’s edge and he stretched his hand over the water. At once the waters drew back, left and right, and a straight dry road appeared. Senan led the cattle along the dry road across the bay. When they had crossed over, he drew his hand over the waters again and they closed up, as if they had never parted. He said then that the waters of Poulmacsherry Bay would never be parted again. One time, Clare County Council planned to make an earthen bank across the mouth of the Bay. They started the work, but just before it was completed, the tide swept it all away. The people remembered St Senan’s words, and they did not try that again.

One day, the young Senan was out walking with his mother, and after a while she became thirsty. There was no spring close by, so he bent down and plucked a rush from the ground. Where he pulled the rush a lake sprang up, and a well of good spring water. These became known as St Senan’s Well and St Senan’s Lake, and people say the lake water has a cure for any disease of horses and cattle, and is good for crops, as well as a remedy for toothache.

On another occasion, Senan and his mother approached a village where they had hoped to spend the night. The people made it clear they were not welcome. They spoke crudely and made foul remarks that insulted Congella. When the pair still did not turn away, the people pelted them with stones. Senan’s mother was most perturbed, but then her son told her that God avenges all wrongs done to his servants. After that, a plague fell upon that village and all of its inhabitants and their cattle died. Not one survived and the village itself was later swallowed up by the sea. Some people say this might be the sunken town of Kilstapheen.

As a young man, Senan was obliged to fulfil the duties of an ordinary man of his tribe. He therefore had to take part in an expedition against his tribe’s enemies. The men of Corca Bascin marched against the men of North Clare, and did battle at Corcomroe. Senan took no part in the fighting, but he witnessed his tribe’s defeat, and when he was pursued by the enemy, he hid himself inside a stack of corn. As the soldiers approached, suddenly the stack of corn seemed surrounded by flames, although both Senan and the corn were quite unharmed. Believing they had witnessed a miracle, the enemy soldiers spared Senan’s life and let him go.

As he was making his way back to West Clare, Senan got very hungry and had to beg for food. He came to the home of a petty chieftain and asked for a bit of bread there. The chieftain was not at home and the servants refused to give him anything. Turning away still hungry, Senan was angry and cursed the food on their chieftain’s table. The chieftain retuned soon after, and observed that the men at his table seemed to be talking nonsense and behaving oddly. When he asked his servants had anything unusual happened in his absence, they told him the saint had come begging but they had turned him away. The chieftain sent a messenger with a spare horse to bring Senan back with him for dinner. When Senan said a blessing on the food and enjoyed his hearty meal, the chieftain’s men returned to their normal selves.

Senan had already shown signs of greatness from childhood. The miracles that manifested around him marked him out as touched by the hand of God. He travelled around Ireland, firstly in training as a monk at Kilnamanagh in Ossary. He made a pilgrimage to Rome, returning via the shrine of St Martin of Tours in France. He became a bishop and built churches around Ireland, living a long life as a man of God before he returned to West Clare to found his monastery there. A vision brought him back to a small island in the Shannon estuary, Inis Cataigh, now called Scattery Island.

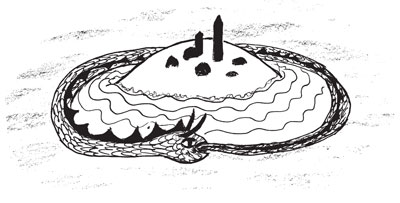

The place was named after the Catach, a ferocious sea serpent or peist that lived in the waters that surrounded the island. This peist had a formidable reputation. She would capsize boats and devour the hapless sailors. She was rumoured to be over 3 miles in length, and could sleep coiled around the island, with her tail in her mouth. No one would dare go near the island for fear of the Catach. Some said she was a dragon, others described her as having the appearance of an enormous eel with a line of sharp barbs along the length of her back and a mouth full of sharp teeth. Near Kilrush there is a Gleann na Peists, where the monster was said to have deposited stones brought from the island.

Senan had no doubt heard stories of the Catach since his childhood. Now he must do battle with the peist if he was to claim the island for his holy community. It was an angel that transported Senan to the island to face the beast, and the very spot where the angel put him down is known as Knockanangel Hill. Senan spread his arms wide in prayer and called to the Catach to show herself and be ready to meet the new master of Inis Cataigh.

The Catach rose to the saint’s challenge, advancing towards him with red eyes flashing like flames, spitting venom and stretching her jaws wide. The serpent swerved aside and swallowed Naroch, Senan’s smith. However, the saint was able, with some words of power, to rescue the smith from the monster’s jaws. Naroch was understandably shaken, but quite unharmed and enormously grateful.

Senan faced the beast without fear. He held aloft his golden cross and spoke, commanding her to give up her claim to the island. His words held power, his faith was certain, his trust in his God unshakable. The Catach, seeing the superior power of the saint, recognised there was no choice and surrendered. St Senan bound the monster with chains and banished her to Doolough Lake to the south of Mount Callan, commanding her to do no harm there. Only when the weather is wild does the serpent stir in that dark lake, and the surface of its waters seems to boil like a great pot over a stove. The beast herself is seen there once every seven years.

Having won the island from the Catach, St Senan prepared to build his church there. But the Catach was not the only one to oppose him. MacTail, the ruler of Hy Fidhgial, was furious when he heard the saint had taken possession of the island without his consent. MacTail sent his druid to confront the saint. The druid commanded a mist to cover the island, but St Senan dispelled that swiftly with a prayer. The druid then called darkness to fall, and again the saint overcame the druid’s magic. Whatever the druid commanded, the saint dispelled. At last the druid left, disheartened, landing with his followers on Dair Inis, the island of oaks, where a great wave drowned them all as they stood at a rock known afterwards as Carrig an Draoi, the druid’s rock.

MacTail then came to speak to the saint himself. He brought two horses with him, and ordered the saint to see to their care. When the saint refused, MacTail shouted and swore at him, and the saint called back, the excitement causing the horses to become distressed. As they reared and whinnied, the ground beneath the two fine horses gave way and swallowed them up. (That spot is known as Fan na nEac.) This only further stoked MacTail’s fury.

‘What a pointless waste of fine horse flesh!’ MacTail railed against the saint. ‘You do not scare me with your magic tricks, holy man. I am not afraid of you or your God, any more than I fear a shorn sheep!’ Those words came back to haunt the unfortunate chief, when some time after he was thrown from his chariot when his horses shied at the sight of a sheep.

There was no spring well on the island at that time, and the monks suffered greatly from the lack of good water. They had to fetch it in buckets from the mainland, both for themselves and for their cattle and sheep. At last they spoke to St Senan about their plight. The saint rooted up some earth with his staff, and where he had dug, a spring well bubbled up, of good clear water. The monks were grateful to be saved the work of carrying water; now they could devote more time to praying. St Senan stuck his staff into the loosened ground beside the spring, and it took root and grew into a hazel tree.

Which makes me wonder, did the hazelnuts fall into the well, and were they eaten by a salmon? For that is what happened at another well hundreds of miles away where the River Shannon began, ah but that is another story altogether and not a story I have heard told down at this end of the Shannon.

At last, St Senan could begin to build his church. He built the Church of the Angel beside the spot where the angel had deposited him on the island. There is a mound of earth beside it that bears the marks of the saint’s elbows and knees, where he knelt in prayer before banishing the Catach.

Many came from all over Ireland to visit St Senan. Holy men from other centres of the Christian faith, including St Brendan of Birr and St Kieran of Clonmacnoise, came to ask St Senan’s counsel on sacred matters, such was his reputation for wisdom. The island was known for its hospitality. All visitors were made welcome – that is, unless they were female! The saint had one simple rule: he would allow no woman to set foot on the island, no matter how holy she might be. There were female saints who would have liked to visit, for reasons many and varied.

A woman named Cannera came from a community of holy women at Cill na gCailleach in Querrin. She was very sick; in fact, she knew that she was dying. Despite her sickness, she had travelled in the hope of speaking with the saint. It was her dying wish. A messenger brought word to the saint, and he looked offshore to where St Cannera lay in her boat. Despite her obvious devotion, still he would make no exception to his rule: no women on the island. She pleaded and said, ‘Women are just as welcome to enter the kingdom of heaven as are men.’ At this, the saint relented, sending one of his brothers out in a boat to give the dying woman her last rites. However, he still would not permit her remains to be buried on the island, but rather allowed her to be buried at the low tide mark, where the waves roll over her grave to this day.

St Brigit herself would have come, but St Senan would not allow even her on the island.

There was a kinswoman of St Senan’s living with the holy community on Inis Cealtra in Lough Derg. She made a new set of vestments for the saint, and wanted to present them to him in person. Now, maybe she needed to do a final fitting to make sure they were not too long for the saint, but whatever her reasons, St Senan would have none of it. He sent her a message saying, ‘Put the vestments in a wooden box and set it in the river. Let the water carry it to me with God’s grace.’ She duly did as he asked, and the wooden box floated down the Shannon. The vestments landed safely at Scattery Island, and I can only hope they did indeed fit the saint properly!

One day, a dispute arose between St Senan and some of the other holy brothers who had come to visit him. It was a simple difference of opinion, but they found they could not settle the matter by themselves. They were setting off on a journey and they prayed for guidance, asking God to give a sign to show which of them was in the right. All the brothers prayed fervently, their eyes wide open to see if there was a sign yet. After a short while, along the way between Kildimo and Farrighy, the brothers saw a golden bell descend slowly from the heavens. The brothers watched as the bell came to land at St Senan’s feet. That was sign enough for them and they gave up their dispute. None of the brothers doubted St Senan’s wisdom after that sign, and accepted that he was always naturally in the right.

The bell had powers of its own, as a bell from heaven no doubt should. It had the power to expose liars and criminals.

Once a Galway man lost a large sum of money. He believed it had been stolen, so he sent his servant to borrow the golden bell from St Senan. He was desperate to discover the culprit and see him suitably punished. St Senan happily gave the bell and the servant set off for home. Now, it so happened that it was the servant himself that was the thief, and now he was afraid that the bell would uncover his deceit. The man went into quite a panic, wondering what he should do. He threw the bell into the river and continued on home. When he reached Galway, he told his master that the saint would not give him the bell. His master replied, ‘I believe you are a liar and a thief! What do you think this is sitting on the table before me?’

There on the table sat the golden bell. The servant was shaking all over as he confessed his crime. He gave back all the money he had stolen and the golden bell made its own way back to Scattery Island. The bell was still in use for testing truth or guilt in the nineteenth century.

St Senan was buried on Scattery Island, and all the chieftains of west Clare were buried there too. An elder tree grew by his grave, and it was considered unlucky to cut or break a twig from it.

For all his misogyny, St Senan’s protection over the island meant that in its later years, when the Shannon river pilots and their families lived in a street of houses there, no Scattery Island woman ever died in childbirth.

Perhaps, after his death, with the wisdom of hindsight, St Senan relaxed a little and extended his blessings to women after all!

There was an old woman who lived in County Clare long ago, who was the proud owner of a pig. The pig was her beloved prize possession and she cared greatly for it. So, when the pig suddenly fell sick one day, the old woman was terribly worried about it. The pig would eat nothing and simply lay on the floor groaning, while its breathing came in loud fits and starts.

There being no vet around the place in those days, the neighbours suggested the woman should go and visit the parish priest, to see if he could help. The power of prayer being a great thing, perhaps a cure might come from that.

The old woman went at once to see the parish priest and told him her sad story. The priest was doubtful that he could help, having no experience with animals himself, but the woman would neither be satisfied, nor silent, unless he would come to see the pig.

At last the priest relented and came to the old woman’s house. He knocked upon the door and the woman brought him inside. There he found the sick pig, lying in the corner of the room. He leaned over the pig, and the smell was something terrible. He wanted to hold his nose and could hardly help but retch at the stench. Mostly he wanted to get out into the fresh air as quickly as possible, but for the old woman’s sake he said a few quiet words over the creature as if he was in prayer.

‘Well now, if you live, you’ll live, and if you die you’ll die. But whether you live or you die, you are no great loss.’

The old woman was grateful and thanked the priest for his ‘blessing’.

As it happened, the pig recovered and was soon back on its feet. The woman was delighted and believed that the pig lived thanks to the priest’s few quiet words.

Some months later the old woman heard that the priest himself had taken sick. In fact, the poor man was gravely ill. The doctors said that he would die, and the only thing that might save him was if he was able to give one long, hearty laugh.

When she heard how sick he was the woman decided she must visit the priest before he would meet his maker. She knocked on the door, but the housekeeper would not let her in. She argued and made her case, and at last she was let in past the doctors and the relatives to the sick room where the priest lay dying. He was a sorry sight: his hair was matted, his skin was grey, and he looked frail and old despite his years as he lay propped up on a pile of pillows under a plump embroidered eiderdown.

Going over to his bedside she spoke the words which the priest had uttered over the sick pig, believing them to be a blessing with great healing power. ‘Well now, if you live, you’ll live, and if you die you’ll die. But whether you live or you die, you are no great loss.’

When he heard these words, the priest burst into a hearty laugh. This being just what the doctor had ordered, he was immediately cured and soon back to his old self.

There was a good but ignorant man who never went to mass. In all the rest of his ways he lived well, never speaking a bad word about any of his neighbours and treating all he met with respect and politeness. He worked hard and stayed away from liquor.

But the people told the priest that he would not go to mass, and so the priest paid him a visit. Well, the good man had not heard about prayers and did not know that he should be going to mass at all! So when it came time for mass the next time, he went along.

When he sat down, there was a sunbeam in front of his seat. The good man took off his coat and hung it on the sunbeam and there it stayed, just as the good St Brigit had hung her cloak on a sunbeam to dry long ago!

The next time he went to mass, there was the sunbeam again. The man took off his coat to hang it up. But this time it would not stay. He said, ‘That was my first sin. I was too proud that the people had noticed the small miracle.’

There was a time in the 1850s when the practice of Roman Catholicism was suppressed on the Loop Head Peninsula. Protestant landlords would give the priests no land for the building of a church.

Marcus Keane, a land agent who lived in a large house in Kilbaha, was responsible for the building of a Protestant church there and a number of schools on the peninsula where the Protestant faith would be taught. As the people were only beginning to recover from the Great Famine, the food provided to children at these schools proved a huge incentive to families renouncing their Catholicism. Considerable pressure was also put on tenants who were threatened with eviction if they would not surrender their religion.

The parish priest, Fr Meehan, began building schools for the Roman Catholics in order to preserve his faith on the peninsula. He knew that what was needed was a church where his flock could gather, but there was no building available. He held mass in his own home for a while, but was soon evicted. He, along with other priests, tried a number of temporary solutions, including tent-like shelters of wooden poles and canvas, without success, as the wind and rain proved too strong for them and continually blew them down.

At last an inspired idea came to him. If there was no land in the area that was not owned by Protestant landlords, then he would use the strip between the sea and the shore, which was owned by no one. This space between the high and low tide lines was a kind of no man’s land, and it would surely not be illegal to congregate there.

So far so good, but what would he do for a shelter? Well, around that same time, the bathing machine was in use on fashionable beaches. These ‘machines’ were small huts on wheels that were used to preserve everyone’s decency. Bathers would change into their bathing costumes and be wheeled into the sea, where they could slip into the waters without their bodies being exposed. Did Fr Meehan find his inspiration from seeing these in use on the beach at Kilkee? Whether it was divine inspiration or a bit of lateral thinking, who knows. The priest had a carpenter in Carrigaholt build him a wooden shed on wheels, with windows on both sides and an altar opposite the door. When it was finished, he had it brought to Kilbaha where it was no doubt greeted warmly.

Each week he wheeled this strange contraption down to the space between the tide lines and held a mass on the shore in Kilbaha from the ‘Little Ark’ as it began to be called. His faithful congregation of up to 300 knelt in the mud and sand to pray, regardless of the weather. There were marriages sealed there, and babies baptised in the odd little shelter between the sea and shore. People came from far and wide to see this strange phenomenon, and many were amazed at the lengths people would go to to practice their faith.

Some years later, land was finally granted to Fr Meehan for a church building at Moneen. Whilst the church was being constructed, mass was still celebrated from the Little Ark, which was transported to Moneen and eventually moved into the building. The Little Ark was moved into its final resting place within an annexe to the church building, where it remains to this day.

At one time there used to be a lot of traffic on the River Shannon. It was almost easier to move about on the water than on the land, and the river would have been one of the main thoroughfares. There are a lot of islands in the Shannon, and one of them, near Bunratty, is called Saints Island.

There were people called McInerney who lived on that island. They kept a few cows; Mrs McInerney, she had a number of chickens; and her husband, he went out fishing in his boat. They had a baby, probably the first of many that would follow, God willing.

One day, when Mr McInerney was out fishing, away from the island, a boat came up the river and pulled in on the shore. Mrs McInerney didn’t see it for she was in the back room at the time, settling the baby to sleep.

There was just the one man in the boat, a rough-looking fellow who was up to no good. He saw the house, the only house on the island, and he headed towards it. He was calling out ‘Hello. Hello,’ pretending to be friendly, but nobody came out to see who was approaching. Since it looked as if no one was around, he just went right inside the house and started opening the dresser drawers and pulling out whatever he found in there. He was looking for money and gold watches, jewellery, that kind of stuff. He didn’t find any of that, nor anything else that was much use to him, so he went through to the other room then, to see could he find any valuables.

All this time Mrs McInerney was in the other room. She must have fallen asleep herself when she was settling the baby, until the sound of doors banging and drawers being opened and things being thrown about must have woken her up. She jumped up and was standing there frozen with fear, with the baby, her most precious possession, in her arms, when the robber came into the room. There was nowhere she could hide. The man had the wild look of a hunted animal in his eyes. There was a scar down the side of his face and his hair was all scraped over to one side.

When he saw her, he shouted at Mrs McInerney to give him her valuables. Mrs McInerney said, ‘The only thing I have of any value is my own baby boy.’

‘Well now Mrs,’ said the robber, ‘If there’s nothing else worth anything, then I’ll take the child. There’s rich folk in London would pay good money for a healthy baby boy!’ The robber threatened terrible things if she would not give him the child. Mrs McInerney backed away as he reached to grab the child from her arms. She got past him through into the other room, all the time crying out a desperate prayer to all the saints that she knew the names of to save her child. The first thing she saw in the other room was the milk churn. A sudden inspiration came to her: she could hit the man with the churn staff!

It must have taken all her courage and all her strength, but when the man came after her, she hit him over the head. He fell down dead and Mrs McInerney and her child were saved, thanks to all those saints she had prayed to. After that the island was known as Saints Island.

There was a man called Muirisheen who lived in Fodera, down near Loop Head, in a mean little cabin with a door painted red, a briar bush by its side and a rough path leading down to the shore. He never had much at all, but he lived well enough and slept easy in his bed each night. Until one night Muirisheen had a strange dream that woke him early in the morning.

In the dream he was on the quays in Limerick where he met a man who gave him gold and treasure, so that he would never be in need again. The first night he dreamed it, he thought, ‘Well, that would be a fine thing to meet on the quays in Limerick!’ and he laughed at himself and fell back to sleep again.

The next night, when he woke from the same dream, he laughed again at his wishful thinking. But when he dreamed the same dream on a third night, he began to think there might be more to it. He went to see a little old woman who lived nearby and told her about the dream. She advised him, ‘Well, unless you go to the quays in Limerick, you will never know what awaits you, whether it be good or bad. What will you do Muirisheen?’

Muirisheen decided to set off that morning, before he could change his mind, to see what fortune he might find on the quays of Limerick. It was a long way round to walk by land, so Muirisheen got himself a place on a boat bringing turf to the city. The boat stopped at Scattery Island and some of the other small places along the Shannon on the way.

When they reached the quays of Limerick, Muirisheen helped the men unload the cargo of turf. When that was done, he leapt ashore and walked up and down the busy quays. There was so much activity there, with men and ponies carrying loads from the boats into the town, he didn’t know where to look for his fortune. He wandered up and down the quays, searching for the man and the gold. He asked a number of people, if they had his fortune, but no one had the slightest clue what he was talking about. At last he sat down on a big stone and took off his hat, wiped his brow and started to wonder if he was just a madman who had come to Limerick following a false and foolish dream. Had he made a wasted journey? Perhaps he should start walking for home? There was a long journey ahead of him if there was no boat going down the Shannon that day.

As he sat there, lost in his thoughts, a man in a black overcoat and a tall hat came up and asked Muirisheen what was the matter with him, ‘Are you lost, man? Are you looking for someone? Can I help you find your way?’

‘I am glad that you asked me, sir. Thank you for your kindness and may God reward you. My name is Muirisheen Fodera and I came all the way to Limerick quays to seek my fortune. You see, I have had a dream for three nights running that I would meet a man here who would give me gold and treasure. I have been here half the day now, and found no one, no gold, nothing. Am I just a fool to have come this way?’

‘Hah!’ said the man in the black overcoat, ‘I have also dreamed of finding gold and treasure. These last three nights I dreamed I found gold under the threshold stone of a little mean cabin in a place called Fodera. I saw the place clearly in the dream. The door was painted red, there was a briar bush by the side, and a rough path leading to the shore. Sure, they are only dreams, man; there is no truth in them. I would not waste my time looking for such a place, when I know that if I work hard enough here in Limerick, I will make my own fortune. Go home, Muirisheen Fodera, go home.’

Muirisheen shook the man’s hand, ‘Thank you for your wise counsel, sir. May you never know how it has helped me. What a fool I was to seek my fortune here. I will leave for home at once.’

Muirisheen asked all along the quays until he found a boat heading down the Shannon that day.

When he reached his mean little cabin, he fetched the crowbar and set to work. After an hour or two he managed to raise up the threshold stone. Underneath there was a wooden chest with metal catches sitting upon an old griddle. Muirisheen raised the lid and found it full of gold coins and jewels. He sat himself down and wiped his brow, and laughed out loud, ‘Ha ha, so is Muirisheen Fodera a fool to follow his dream? Well, if I am, then it is a rich fool I am!’

He kept the griddle, for there was decoration on it and something written, but Muirisheen could not read it. He polished it up and put it on his mantelpiece, and wondered what he would do with the gold.

A few years later a poor scholar travelling around the country stopped at Muirisheen’s house for refreshments. It was no longer a mean little cabin, as Muirisheen had made a few improvements to the place. The scholar was enjoying his cup of tea from the china cup, when he saw the griddle above the mantlepiece. ‘Where did you get that griddle?’ asked the poor scholar.

Muirisheen was reluctant to answer. ‘Why do you want to know?’ he asked suspiciously.

‘Well,’ said the scholar, ‘it is the words engraved upon it, my dear host, that may be helpful to you.’

‘I kept it for the decoration on it. It looks fine there above the fireplace, does it not? I could not read the writing. Tell me, scholar, what does it say?’

‘It says, ‘Whatever is found on top, there is as much again beneath.’ Does that have any meaning for you, sir?’

Muirisheen did not wait to answer. He went at once to fetch his crowbar and shovel. The poor scholar watched amazed as Muirisheen raised the threshold stone and dug down into the gravel beneath. The shovel rang out as it struck something. Muirisheen cleared away the gravel and brought up another chest. When he raised the lid, there was another heap of gold coins and jewels!

The poor scholar helped carry in the chest, and Muirisheen rewarded him with a pocketful of gold.

There was a story recorded up around Caherhurley about one of the last of the O’Briens. This man was returning over the mountain to Kincora, on his way home from a battle. He was not travelling alone, but had with him a faithful servant who had been with him for many years. When they reached the point where Kincora came into view, instead of the fine palace in all its glory, they saw it masked by smoke and flames leaping all around it. O’Brien feared that his end was surely near. He knew he dared not go to Kincora himself, as his enemies were awaiting his return. Instead, he told his good servant to go to Kincora in stealth, trusting that the enemy would not harm him. He instructed the servant to search in a particular location and to bring his treasures from their hiding place to O’Brien, up on the mountain.

As evening drew near the servant obediently set off and quickly reached the spot his master had described. He found O’Brien’s treasure, filled a sack with gold coins and glittering jewels, and made his way back to the mountain under the starlit sky. O’Brien and the servant worked together to conceal the treasure securely under a pile of stones. When this was done, greed overcame the servant. Only he and O’Brien knew the whereabouts of the treasure, and the two of them were alone on a lonely hillside. No one need ever know. The servant took up a rock and struck his master. O’Brien fell down dead, and the servant covered his body with stones. Now no one but him knew the location of O’Brien’s treasure.

The servant let it lie well alone for a few years. Indeed, he thought little of the treasure on the mountain, until the time came that he was to be married. Then he confided in his wife-to-be that he knew the location of a hidden treasure, and that he had best go and ensure it was still safe up on the mountain. Of course he did not tell her how this treasure had come into his possession.

It was a muggy sort of a day when he took himself up the mountain again. The air was warm and heavy, as if thunder might come. When he came to the place where the gold and jewels were concealed, he went first to stand over the grave of his former master. Perhaps he meant to say a prayer, or to ask forgiveness, but that we will never know, for before he opened his mouth to say a single word, he was struck by lightning. As the thunder clouds rolled over, he fell to the ground, stone dead beside the grave of the man he had slain for greed.

When he did not return home as expected, the bride gathered a party of men to search for him. They were not long up on the mountain before they found the servant’s body, and close by, another corpse. Now the story became clear, and the servant’s treachery was discovered.

The men buried the two bodies there on the mountain. They buried O’Brien’s remains in a spot where the sun could always shine on his grave. The faithless servant’s body they buried in a spot where the sun never reaches. There were no grave markers erected, so today no one knows quite where on the mountain those graves are to be found. Nor do we know if the treasure was ever discovered. For all I know, it may be lying there still, under its covering of stones, just waiting for some fortunate walker on the East Clare Way to find it.

Saints: SFS (1937-38), Wan O’Dwyer and May Keane heard this from their parents, reel 180; SFS (1937-38) Thomas Casey and M. McDonnell, Lough Burke, Kilmaley, told to John Casey, Feighro, Kilmaley, p.54; SFS (1937-38), Tim Sexton, Deermade, told to John MacGrath, Lissycasey, p.450, Reel 177.

St Senan: SFS (1937-38) Paddy Malone heard from Martin Howard, Ballyvaskin, reel 179; Patrick Cleary and others, recorded by Michael Twomey, Burrane School, reel 176; p. 19, reel 179; John Cunningham, reel 180; Anon, Kilrush, reel 181; Folklore of Clare, T.J. Westropp (Clasp Press; Ennis, 2000).

The Old Woman and the Pig: SFS (1937-38) Kitty Williams Carnacalla, Kilrush told by her mother, reel 180.

Pride: SFS (1937-38) Joseph Bonfield, reel 180.

Saints Island: SFS (1937-38) Mrs J. Quinn, Cloughlea, Sixmilebridge, Sixmilebridge NS, p.387.

Muirisheen Fodera Follows His Dream: SFS, Batt Scanlon, Doonaha.

Treasure and Treachery: SFS (1937-38) John Malone, Caherhurley, Caherhurley School, p. 279, reel 174.