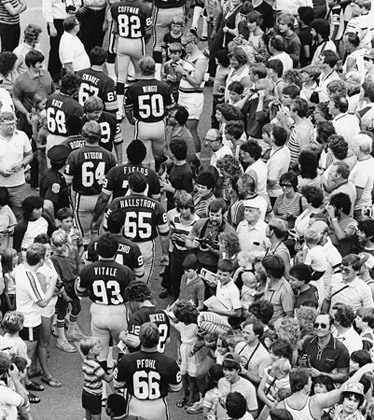

The Packers’ inability to recapture Vince Lombardi’s winning ways didn’t deter fans from supporting the team on a yearly basis. At the team’s training camp in 1982, several Packers including Paul Coffman (82), Karl Swanke (67), Rich Wingo (50), Greg Koch (68), John Anderson (59), Del Rodgers (35), Syd Kitson (64), Ron Hallstrom (65), Lynn Dickey (12), and Larry Pfohl—aka professional wrestler Lex Lugar—(66), interacted with fans between practices. (FROM THE GREEN BAY PRESS-GAZETTE ARCHIVES, REPRINTED BY PERMISSION)

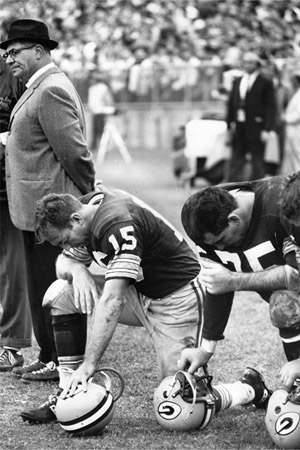

The Packers, only seven years removed from their Super Bowl II victory, were now rife with dissension. During the final weeks of the 1974 season, a quiet conspiracy began gaining momentum throughout Green Bay—an underground campaign of whispers to bring back Bart Starr, Vince Lombardi’s trusted field general, as the team’s next head coach. Once Dan Devine’s resignation was made public, even a reluctant Starr understood why he was perceived as the public’s romantic solution to fixing a franchise in shambles. “The Green Bay Packers organization had deteriorated to the point where it was one of the worst in pro football,” Starr recalled. “I was intrigued by the challenge of fielding an NFL team as well as rebuilding the Packers to the point where they would be as respected as they had been during the Lombardi era.”

Although the Packers were rumored to be interested in retired NFL players Jack Pardee and Norm Van Brocklin as possible successors to Devine, Starr set himself apart during his interview with the team’s executive committee. “He handed out typewritten brochures, which had been prepared by [former Packers’ publicity chief Chuck] Lane, outlining his qualifications and also a rather complete plan of action if he were named to the job,” executive committee member John Torinus remembered.

On December 24, 1974, the Packers announced that Bart Starr had signed a three-year contract as their next head coach and general manager. “The decision of the Packer executive committee to appoint me,” even Starr admitted, “was based on emotion rather than logic.”

Starr had only one year of coaching experience—as an assistant on Dan Devine’s staff in 1972—but “Dominic Olejniczak, our team president at the time, told me that the fans really selected this coach, that they almost demanded that he be hired,” future team president Bob Harlan recalled. “That was a great description of the situation because the fans couldn’t wait for Bart to take over.”

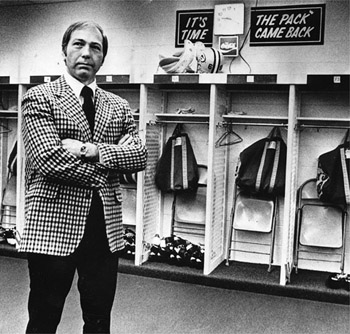

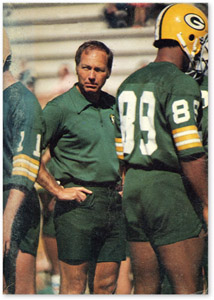

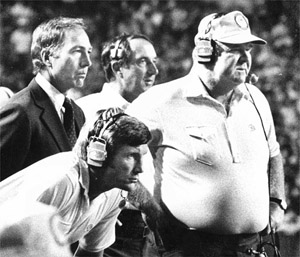

When Bart Starr was named head coach and general manager of the Packers on December 24, 1974, he looked to instill the sense of glory Vince Lombardi had brought to the team fifteen years earlier. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

Starr was now overextended with the responsibilities of being both the team’s head coach and general manager. “This franchise had such incredible success with Lombardi serving in the dual role of coach and general manager that it just seemed that was the way things ought to be done,” Harlan explained. “One man coached and also ran all the other football business, answering only to the executive committee.”

To assist him in rebuilding the Packers’ roster and overall operations, Starr restructured the front office, making Bob Harlan (Devine’s assistant general manager) now the corporate general manager and Tom Miller (who had been an assistant general manager under Lombardi) the team’s business general manager. Harlan was now in charge of all administrative personnel, the public relations department, and negotiations for all player and assistant coach contracts. Miller became the liaison between the front office and the executive committee, serving as the team’s purchasing agent for all phases of the operation and supervising ticket operations in Green Bay and Milwaukee. Starr would have enough support to allow him to focus on fielding a winning team, despite the adverse financial situation he inherited from his predecessor.

Although the Packers hadn’t lost money in 1974, as team president Dominic Olejniczak had first feared, their annual profit had dipped to its lowest level in fourteen years. Team treasurer Fred Trowbridge announced to stockholders that the team’s 1974 profit amounted to $128,425, compared to $680,242 in 1973. It was the Packers’ smallest profit since 1960, when the club made $115,125. “Our operating expenses rose primarily because of higher salaries, number one, and number two, because of keeping more players longer from the time training camp opened until the player strike was called off,” Trowbridge told the crowd of 115 stockholders, representing 2,480 of the 4,656 shares in the community-owned, nonprofit corporation. Trowbridge explained that competition for players from the World Football League had inflated salaries, but that this would be offset in the upcoming year by the NFL’s new network television contract, providing the team with an increase of $529,974 in income. The Packers would also receive another influx of $241,567 from the NFL’s two new expansion franchises.

Earlier that decade, when the NFL announced it would expand from twenty-six to twenty-eight teams, commissioner Pete Rozelle explained that cities would be considered for an expansion team based on their stadium, weather, sports interest, and growth potential. By the spring of 1974, the list of hopeful cities that once included Indianapolis and Jacksonville had been narrowed to five: Honolulu, Memphis, Phoenix, Seattle, and Tampa. That group was thinned to four when NFL owners awarded Tampa, Florida, the twenty-seventh franchise. Less than two months later, the owners welcomed Seattle into the league. The two franchises paid a then-record $16 million entry fee to begin play in 1976.

Back in Green Bay, Bart Starr’s return had infused a sense of hope around the Packers’ training camp unseen since the early days of Lombardi. “The atmosphere in the organization changed tremendously once Bart Starr arrived. It was almost a feeling of relief because everyone really believed he was the right person for the job,” Harlan recalled of the team’s fresh start. “The people in our building were as excited as the fans on the street.”

Upon taking the job, Starr would have to replenish one of the oldest rosters in the league if the team’s fortunes were to turn around. “Right away we began to evaluate the Packers’ existing personnel and became very concerned,” Starr said of inheriting nine players over the age of thirty and four more at twenty-nine. “The reasons for the Packers’ decline after 1968 became more obvious; the organization had failed to adequately plan for the replacement of its quality veteran players.”

The NFL’s college draft would provide Green Bay with few opportunities over the next two years. The Packers had relinquished the ninth, twenty-eighth, and sixty-first overall picks in the 1975 draft and the eighth and thirty-ninth overall picks in 1976 as part of the John Hadl trade. Suffering from a lack of talent, “we were no better than most expansion teams and worse than some,” Starr remarked.

More than 1,500 fans turned out at the Packers’ training camp every day, forming a corridor from Lambeau Field to the Oneida Street practice field, all for the chance to see the return of Bart Starr. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

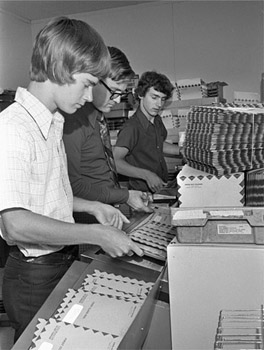

Although Lambeau Field had been sold out consistently since 1960, Bart Starr’s return brought added enthusiasm to season-ticket holders. Here (left to right) Kevin Kuehn, Jim Heintzkill, and Chuck Kuehn processed and mailed more than 50,000 sets of season tickets to 1975 Green Bay Packers games. (COURTESY OF THE PRESS-GAZETTE COLLECTION OF THE NEVILLE PUBLIC MUSEUM OF BROWN COUNTY)

Starr also eradicated the cancerous personalities from a Packers locker room where losing had become contagious. “Unfortunately, he was unable to replace these people as fast or as quickly as he thought he could,” Torinus remarked, “and from his first season on, he suffered from a serious lack of depth in key positions on both offense and defense.”

It didn’t take long for the Packers’ personnel weaknesses to be exposed. In the 1975 season opener, the Detroit Lions blocked three of Steve Broussard’s nine punts to set an NFL record; kicker Chester Marcol tore a quadriceps muscle and was lost for the season. The next week, cornerback Willie Buchanon suffered a broken leg against Denver and joined Marcol on the season-ending injured reserve list. Running back John Brockington went into an early season slump and never regained his old swagger. Quarterback John Hadl failed to return to the form that had made him a star with San Diego in the AFL, throwing an NFC-high twenty-one interceptions. When the Packers started the season with four straight defeats, syndicated columnist Steve Harvey was unsympathetic when declaring, “Packers coach Bart Starr is off to his worst start since 1955, when he helped quarterback Alabama to an 0–10 season.”

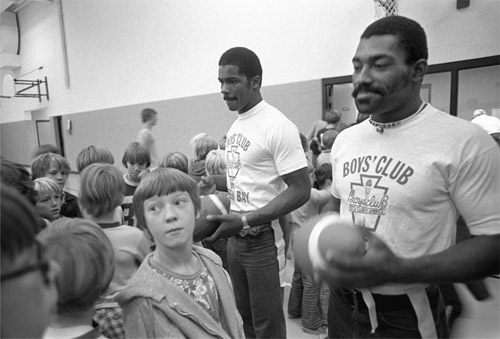

Serving as team ambassadors, safeties Steve Luke (left) and Johnnie Gray (right) were two of several Packers who made public appearances in the months leading up to the 1975 season. (COURTESY OF THE PRESS-GAZETTE COLLECTION OF THE NEVILLE PUBLIC MUSEUM OF BROWN COUNTY)

New head coach and general manager Bart Starr was serious about returning honor and respectability to the Packers organization, on and off the field. (WHI IMAGE ID 88802)

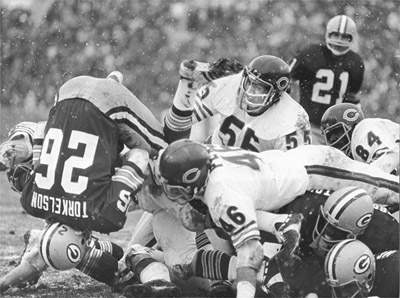

Running back Eric Torkelson (26) and the rest of the Packers found their 1975 season taking a nosedive as they lost eight of their first nine games. (WISCONSIN STATE JOURNAL)

After the Packers nipped the Cowboys 19–17 for their first win of the season, they went on to lose four more games. They finished the season on a positive note with a victory over the Falcons. “Winning three of their last five provided reason for hope, even though the Pack had only a 4–10 record on the season,” Torinus explained, noting the team’s last-place finish in the NFC Central Division.

• • •

The team’s future looked brighter during the annual stockholders’ meeting that offseason. The Packers reported a net profit of $784,830—the highest since 1970, when it had reached a record $1,139,379. They also announced that for the first time in team history, the franchise’s total assets were above the $10 million mark, having reached $10,769,416, up from $9,837,452 in 1974.

Green Bay’s annual stockholders’ meetings and public disclosures of financial records would become even more relevant that year as they became the last publicly owned NFL franchise. The Patriots franchise, which was formed in 1959 as part of the original American Football League, had been public since William H. Sullivan Jr., along with nine other investors, sold nonvoting public stock to raise capital to help post the franchise fee of $25,000. In 1975 Sullivan became the majority owner, and a year later he purchased the remaining nonvoting stock. Once he acquired control of the Patriots, he restructured the franchise into a private corporation, no longer required to divulge its operations. That change left the Packers as the only NFL franchise making public annual income statements, a condition under their nonprofit ownership structure. Five years later, when the league adopted new stipulations in 1980 that prevented ownership of a team from comprising more than thirty-two individuals and requiring a primary owner to maintain at least a 30 percent stake in the team, the Packers’ unique corporate structure would never be matched again. The new ownership rules prohibited publicly owned franchises, making the grandfathered Packers’ corporate structure and annual shareholders’ report a unique document, one that provides unusual insight into the often undisclosed economics of professional sports.

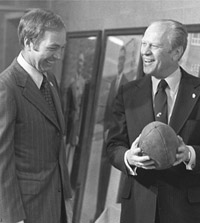

The first Green Bay Packers Hall of Fame opened in 1967 as a series of temporary exhibits in the concourse of the Brown County Veterans Memorial Arena. In 1976 President Gerald Ford (holding football, with Bart Starr at left) helped dedicate the hall’s new permanent home, just up the street from Lambeau Field. (COURTESY OF GERALD R. FORD PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY)

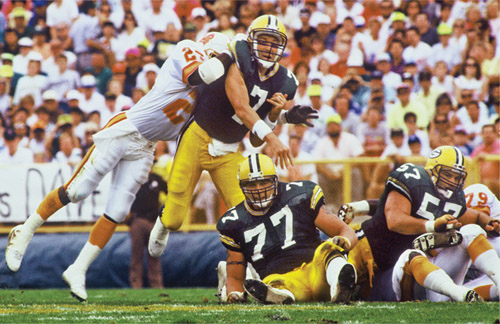

Back in Green Bay, Bart Starr decided the Packers needed a fresh arm. Prior to the draft, he dealt third- and fourth-round picks, along with John Hadl and disgruntled defensive back Ken Ellis, to the Houston Oilers for their backup quarterback, Lynn Dickey. The trade did little to change the Packers’ immediate fortunes, as they lost their first three games of the 1976 season. However, the Packers recovered, stringing together a three-game winning streak. When their record reached 4–5, there was hope for a .500 season. But when Dickey separated his shoulder against the Bears in the season’s tenth week, the Packers’ season unraveled, and they finished last in the Central Division with a 5–9 record. Despite the losing record, Starr told the press he was “pleased with the attitude of the team with respect to the building. Those I know will be with us are smart enough to recognize that we’re still a few people away and, until we get them, it’s going to be tough sledding.” The second-year coach also was appreciative of how accepting the fans were toward what he was trying to accomplish. “I think the fans have been extra good and patient,” Starr was quoted as saying in the Milwaukee Journal. “They deserve a lot better. I really couldn’t have asked for this kind of acceptance.”

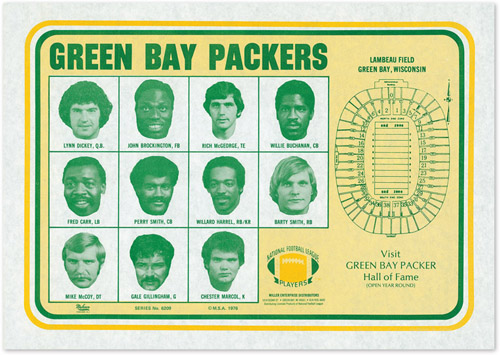

The Packers were the first NFL team with a Hall of Fame devoted to showcasing its history and honoring players, coaches, and supporters. It quickly became one of Green Bay’s most popular and cherished tourist destinations. (WHI IMAGE ID 86639)

Bart Starr (left) surrounded himself with familiar faces and former teammates (left to right) Bill Curry, Zeke Bratkowski, and Dave Hanner as his assistant coaches. (WISCONSIN STATE JOURNAL)

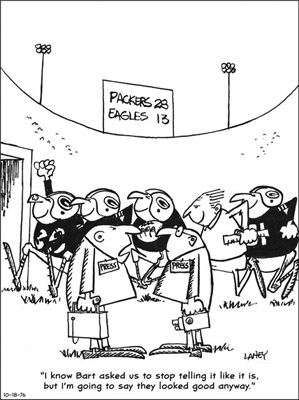

Lyle Lahey’s editorial cartoon reflected the fans’ and the media’s patience with Bart Starr’s rebuilding process; as one reporter said to another, “I know Bart asked us to stop telling it like it is, but I’m going to say they looked good anyway.” (REPRINTED BY PERMISSION OF THE GREEN BAY NEWS-CHRONICLE)

• • •

Although the Packers won one more game in 1976 compared to their previous campaign, the franchise suffered a 42 percent drop in profits, from $784,830 in 1975 to $455,957 in 1976. Team treasurer Fred Trowbridge explained that the drop in income was due to the team’s schedule, pointing out the Packers had large gates on the road in Dallas, Los Angeles, and Cincinnati during the 1975 season. “Where and who we play makes a great deal of difference,” Trowbridge remarked. “We had a good schedule in 1975 that we didn’t have in 1976 and which we very frankly will not have in 1977.” Trowbridge also explained that revenues from television, radio, and program advertising were down. The two new expansion teams in Seattle and Tampa Bay were now part of the shared revenues, but those receipts would increase once the new television contract was negotiated in 1978. The club’s total assets, which topped $10 million for the first time in 1975, continued to climb to a figure of $11,114,159 in 1976. “These figures would seem to contradict a commonly held viewpoint of NFL management that the operation of a football team is more a matter of love than a matter of profit,” New York Times columnist William Wallace claimed.

The NFL Players Association used the Packers’ published economic figures to strengthen their demands. And with a lawsuit that was making its way through the U.S. court system, the NFLPA was challenging the league’s free-agent compensation clause. The Rozelle Rule, which allowed any team that lost a free agent to another team to receive something of equal value, severely limited player movement. On October 18, 1976, the court ruled that the Rozelle Rule was legal and exempt from the Sherman Antitrust Act liability if free agency was accepted through collective bargaining, further clarifying that player movement should be resolved through the negotiation process. As a result of the ruling, the NFLPA had to bargain with the NFL owners. On February 16, 1977, the two sides came to terms on a collective bargaining agreement that eliminated the Rozelle Rule. A first refusal/compensation system governing free agency was created, where the price of at least a first-round draft choice would be the compensation for signing another team’s free agent. The union had obtained improved benefits and grievance procedures, but it hadn’t achieved true free agency or reached its goal of winning 55 percent of league revenues for players. The result set the tone for the 1982 negotiations.

The Packers couldn’t translate their profits into wins on the field. During the 1977 season, patience ran thin in Green Bay as the Packers showed no improvement and in fact seemed to be getting worse. Born out of the frustration of an offense that generated only eleven touchdowns all season, Packers bashing became fashionable, with jokes like “Why is Lambeau Field a safe place in a tornado? Because there are never any touchdowns there” making the rounds. The Packers scored more than 16 points only once all season. Their 4–10 record—enough for another last-place finish in the Central Division if not for the hapless Tampa Bay Buccaneers—fueled speculation that Starr would resign as coach but stay on as general manager. Executive committee member and former Packers star Tony Canadeo came to Starr’s defense, exclaiming, “When you had twelve teams in the league, you could build overnight, but with twenty-eight, you can’t do that. You have to have confidence in your coach.”

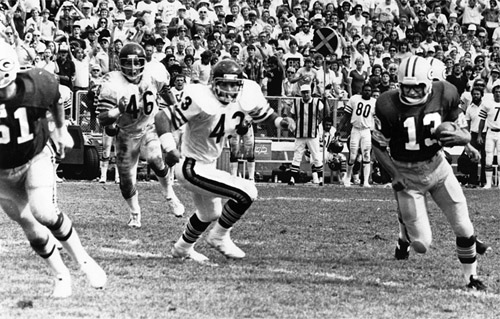

The Packers, decimated by injuries, found themselves unable to catch their rivals, including Walter Payton (34) and the Bears, for most of the 1977 season. (WISCONSIN STATE JOURNAL)

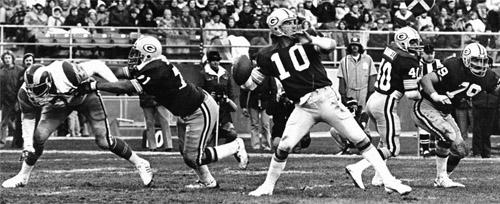

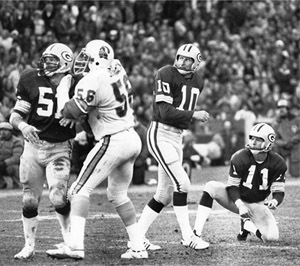

When the Packers traded John Hadl to the Oilers, the team received quarterback Lynn Dickey (10), who had one of the strongest and most accurate arms in the NFL. As long as Dickey had protection and stayed healthy, the Packers had one of the most potent offenses in football. (WISCONSIN STATE JOURNAL)

When Starr’s contract was extended through the 1979 season, despite coaching the Packers to a 13–29 record in his first three seasons, executive committee vice president Richard Bourguignon explained to reporters, “Everyone wanted Bart to get the job and there has been a lot of pressure on him. Now give him a chance.”

• • •

The following spring at the Packers’ annual stockholders’ meeting, treasurer Fred Trowbridge announced that team profits had dipped to just $266,810 for the 1977 season, compared to $455,957 in 1976. The 40 percent decline also represented the lowest net since the $128,425 profit made three years previously, in 1974. “Operating expenses did increase and probably will continue to increase,” Trowbridge explained. “But with the assets we have and the television income we can expect, there is no grave concern for the future of the Green Bay Packers financially.” The team’s total income of $6,567,095 was up $407,025 from 1976 but also showed a $488,238 boost in season expenses of $4,442,800, which included $4.4 million in salaries and bonuses paid to coaches and players—a number that twenty years earlier would have been in the $500,000 range.

To offset the escalating salaries, the Packers, as well as the other twenty-seven NFL franchises, were becoming more dependent on radio and television revenue. In 1977 the Packers received $2,211,122, which Trowbridge explained would increase the following year, when the team would earn $4,842,000 from the networks under the new television contract. The NFL’s new broadcast deal was a four-year, $576 million contract that doubled each team’s annual revenue from an annual average of just over $2 million to $5.2 million through 1981. For the first time, NFL teams would earn more revenue from the rights to telecast their games than from the ticket sales of the games themselves. The willingness of television networks to pay the increased fees further signified that broadcasting NFL games meant guaranteed television ratings.

• • •

A 1978 Harris Poll indicated that 70 percent of the nation’s sports fans followed professional football, compared to 54 percent favoring baseball. The continued rise in popularity allowed the NFL to add more games. In 1978 the NFL expanded its regular season from fourteen to sixteen games and also expanded its playoffs from eight teams to ten, adding a second wild-card team from each conference.

Since the Packers stopped dominating the NFC Central Division after 1967, the Minnesota Vikings had filled the vacuum, winning the division from 1968 to 1971 and again from 1973 to 1977—the Packers’ 1972 crown being the lone exception. With the revised playoff format, the Packers were now poised to take advantage, since “by 1978, Bart had finally gotten rid of most of the head cases,” trainer Domenic Gentile said, referring to Starr’s commitment to adding young players and building for the future.

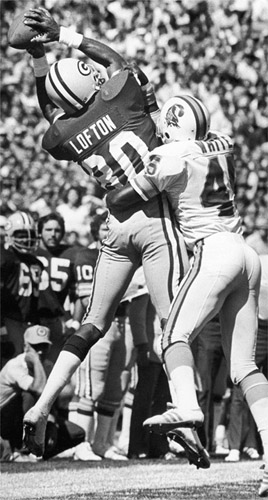

The Packers’ 1978 draft class was its best in years, producing wide receiver James Lofton and linebackers John Anderson and Mike Douglass. One of the most poignant indications of the progress made under Starr’s direction was that eight of the team’s draft choices made the opening day roster that season. The infusion of new talent and a hunger for winning that bordered on starvation helped the Packers win six of their first seven games. All alone in first place, they seemed bound for the playoffs. “Everyone connected with the Packers and the fans were certain their trust and faith in Bart Starr had paid off. The Pack was back!” executive committee member John Torinus exclaimed. “Then the roof fell in.”

In 1978 Terdell Middleton became the first Packers running back to rush for more than 1,000 yards since John Brockington in 1973. The Packers wouldn’t have another 1,000-yard rusher until Edgar Bennett in 1995. (WISCONSIN STATE JOURNAL)

The Packers went on to lose five of their last seven games, beating only the second-year Buccaneers 17–7 and tying the Vikings 10–10. Because of their tie with Minnesota, the Packers were eliminated from the playoff picture on the last day of the regular season. Green Bay’s 8–7–1 record was identical to the Vikings’, but as a result of their loss in Minnesota earlier that year, they didn’t own the postseason-deciding tiebreaker. “Most of the state’s sportswriters described our performance in the second half of the season as a collapse, or at least a mystery. There was really nothing baffling about it,” Starr recalled of how the team had outplayed itself. “We played the second half of the season with little or no chance of sneaking up on opponents.”

Wide receiver James Lofton helped reinvigorate the Packers’ offense in 1978, catching forty-six passes for 818 yards and six touchdowns. (WISCONSIN STATE JOURNAL)

On the field, the Packers’ 1978 performance seemed to vindicate the executive committee’s decision to stick with Starr and his rebuilding process. “Packer fans began to have visions of more winning seasons after that fine performance in the early going of 1978,” Torinus said. “Another draft and a year of experience for the young players figured to give the Packers a real shot at the playoffs in 1979.”

• • •

Despite not making the 1978 playoffs, the Packers still generated a record $1,520,903 profit that season. The seventy-eight stockholders in attendance at the WBAY auditorium for the annual meeting were given a healthy financial outlook that night. The team’s $1.3 million increase from the previous season was due to the lucrative new television contract the NFL had put into effect in 1978, which wouldn’t expire until 1981. In 1978 the Packers received $5,260,803 from television and radio earnings—a hefty $3,057,681 more than the $2,211,122 derived from the same sources in 1977. Although the team’s total income of $9,482,146 was up $2,915,351 from the 1977 season’s figure of $6,567,095, the Packers did incur $883,752 more in expenses: $7,610,667, compared to $6,726,915 in 1977. With the latest financial surplus, the team’s assets now totaled $15,211,863—up more than $3.5 million from the 1977 figure of $11,823,230.

The Packers hoped their 1979 draft class would continue complementing the team’s rebuilding effort. “Of the thirty-three people we’ve drafted and signed as free agents since 1976, there are twenty-eight still on the roster,” Starr explained, noting that twelve of those twenty-eight players were starters. “So we think that is the nucleus of the Packer team of the future.”

However, unlike the team’s 1978 draft, Green Bay’s 1979 draft wouldn’t harvest as many immediate-impact players. After the Packers drafted running backs Eddie Lee Ivery and Steve Atkins, their third selection was defensive tackle Charles Johnson. “The player I wanted to pick was Joe Montana,” Starr later admitted. “At the risk of sounding arrogant, I was a good judge of talent. My most serious mistakes inevitably occurred when I failed to follow my convictions and deferred to someone with more experience.”

Johnson played three seasons in Green Bay but had little impact on the team’s fortunes. Meanwhile, Montana was later drafted in the third round by the San Francisco 49ers, where he flourished under the guidance of head coach Bill Walsh, enjoying a Hall of Fame career and winning four Super Bowl rings. Following the 1979 draft, Starr was convinced the Packers “had an excellent shot at another winning record, as long as we stayed healthy and were able to avoid exposing our lack of depth.”

Midway through the opening quarter of the first regular-season game, hopes that the Packers would make a serious playoff run began to implode. “For the first time in five years, we finally had a running back, [Eddie Lee] Ivery, who could have the same type of impact on a game as Chicago’s superstar, Walter Payton,” Starr recalled. But the rookie running back severed a knee ligament when his foot caught on the Bears’ Soldier Field Astroturf. Ivery would miss the remainder of the season with what was just one of ten serious injuries that tore apart the team’s foundation.

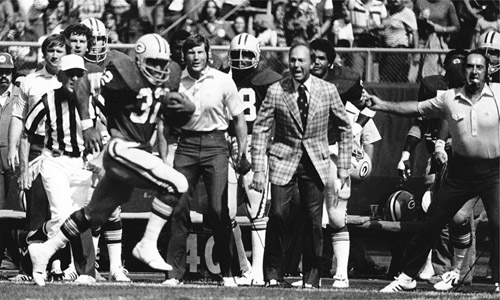

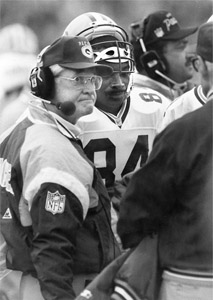

The Packers’ 1979 season had few bright spots, but Steve Atkins’s (32) run from scrimmage against the Saints got the entire Green Bay sideline excited, including Coach Bart Starr, during the 28–17 victory. (COURTESY OF GREEN BAY PRESS-GAZETTE FROM TOM PIGEON COLLECTION)

The Packers found their 1979 season unraveling as injuries once again decimated the team, including running back Eddie Lee Ivery. (WISCONSIN STATE JOURNAL)

From there, Green Bay’s playoff hopes dissolved. They went on to lose one game in overtime, another by 1 point, a third by 3 points, and a fourth by 5 points. When the Packers finished the season with a 5–11 record, many started to question whether Starr would ever coach a winning team in Green Bay. He was further burdened with the fact that the Packers organization had fallen behind the NFL’s elite franchises in many aspects, particularly in the science of evaluating talent. “With the 1980s looming,” author Don Gulbrandsen wrote in Green Bay Packers: The Complete Illustrated History, “the Packers were nowhere close to the team that Starr had once guided as a quarterback, and the prospects for improvement appeared dim. It was a tough time to be a Packer fan.”

• • •

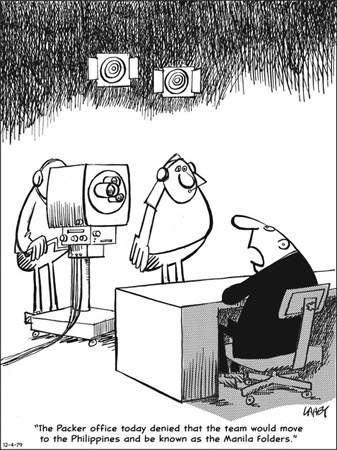

By 1979 the patience of the media and fans had begun to wear thin, as depicted in Lyle Lahey’s editorial cartoon. (REPRINTED BY PERMISSION OF THE GREEN BAY NEWS-CHRONICLE)

For decades the NFL had prided itself on celebrating “the game.” But in recent years, “the money” was overshadowing the sportsmanship being celebrated on the field. By 1980 the corporatization of pro football had made the NFL a multibillion-dollar entity that operated more like Coca-Cola or General Motors than a sports organization. Franchises once struggling to cover payroll were now generating millions of dollars from a variety of revenue streams: tickets, television, merchandise, and advertising. NFL regular-season attendance hit 13 million spectators at the end of the year, marking the third record year in a row and the highest in the NFL’s sixty-one-year history. Stadiums were reporting attendance at over 92 percent of total capacity, and television ratings posted all-time highs.

As the NFL grew more popular and powerful, it began leveraging host cities to fund the construction of new, football-exclusive stadiums, complete with moneymaking amenities like luxury boxes. Cities already hosting franchises were willing to absorb the huge tax burden of building a new football stadium if the alternative was losing their NFL team—a real threat as the demand for NFL teams exceeded the number fielded. During the league’s infancy, any prospective team owner with $50 could join. Now the NFL was cultivating potential cities and owners with extreme diligence. As with any good corporate franchisor, the league saw its product thriving in the best new markets available. With the NFL expressing no plans to expand beyond its current twenty-eight-team slate, a city would promise just about anything to lure an existing NFL franchise to relocate. The cutthroat urban arms race to poach franchises from one city to another was about to begin.

Meanwhile, the Packers fumbled their way through the 1980 NFL draft. With the fourth overall pick, they chose Bruce Clark, who was labeled a “can’t miss guy” by Dick Corrick, the Packers’ director of pro personnel. Clark went on to have a good career, but not for the Packers. He had no interest in playing in Green Bay and chose instead to sign with the Toronto Argonauts of the Canadian Football League before returning to the NFL two years later to play with the Saints and Chiefs. The mishandling of Clark would be considered Starr’s biggest blunder as the Packers’ general manager, one that was caused by his underestimation of the growing “me first” attitude manifesting itself among athletes.

As the team’s head coach, Starr continued feeling some serious heat from the press, which was harping on the team’s apparent lack of discipline. He vowed not to resign after defensive end Ezra Johnson was caught eating a hot dog on the sidelines while his teammates were still on the field in a losing effort. The Packers shook off the hot dog controversy and their winless preseason with a win in their opening game. Three games later, after Green Bay was humiliated in blowout losses to the Lions, Rams, and Cowboys, team president Dominic Olejniczak and the Packers’ board of directors provided Starr with a public vote of confidence in a press release. But the low point of the season was a 61–7 loss to the Bears, part of a four-game losing streak to end the season. Overall the Packers had been outscored 127–30.

The 1980 season opener at Lambeau Field had a bizarre, happy ending for the home team as kicker Chester Marcol (13) returned his own blocked field goal kick 25 yards for a touchdown, giving the Packers a 12–6 victory. (COURTESY OF GREEN BAY PRESS-GAZETTE FROM TOM PIGEON COLLECTION)

Although the Packers hadn’t won a championship in nearly fifteen years, the team was still considered a nostalgic national treasure by many—including presidential candidate Ronald Reagan, who met with Bart Starr at Green Bay’s Austin Straubel Airport during a campaign visit in 1980. (AP PHOTO/CHARLES HARRITY)

Green Bay’s 5–10–1 record found them tied for last place in the NFC’s Central Division. “Packer fans’ patience with Bart Starr began to wear thin during the latter part of the 1980 season. The press became much more hostile, and some of this feeling was reflected to some extent by the Packer board of directors,” Torinus recalled. The board was called into a special session in late December. “In order to save Starr’s job, the committee agreed to proceed immediately with the separation of the responsibilities of head coach and general manager.”

On December 27 the executive committee surprised everyone—Starr included—when they kept him on as coach but took away his general manager title. “I was extremely disappointed in their decision,” Starr said of being forced to vacate the position, which wouldn’t be refilled until 1987. “The logical move, in my opinion, would have been to retain me as the general manager and select a new coach. Our progress in areas most influenced through the general manager’s role had been significant, for we were now a solidly structured organization.”

The executive committee announced that Bob Harlan and Tom Miller would split the general manager duties, but nobody, including Harlan and Miller, knew what that meant. Starr would continue to oversee the football operation as he had as general manager, answering directly to team president Dominic Olejniczak and the executive committee. The lack of clarity surrounding the announced transfer of responsibilities prompted board member Ted Jamison to proclaim, “There is really nothing different after this decision. Miller and Harlan can continue to do what they always did. I think this team needs a general manager, and the board thinks so, too. We don’t have one now, even with this announcement.”

• • •

When the Packers held their annual stockholders’ meeting in May, the executives announced that team president Dominic Olejniczak would assume the additional title of chief executive officer. He would now have complete authority over the operation of the Packers corporation. “The Executive Committee does not want to hire a general manager, an outsider, and turn everything over to him. Committee members want to continue to have full authority on the hiring and firing of a coach, whether they are good judges of NFL coaching or not,” Milwaukee Sentinel sportswriter Bud Lea reported. “This was a complete turnabout from the December meeting when the directors voted quickly, and with virtually no study or research, to separate Starr’s duties as coach and general manager.”

To compensate for the absence of a general manager, the team named Tom Miller as the assistant to the president—business and Bob Harlan as the assistant to the president—corporate, further separating the club’s football and non-football operations. “We wanted to free Bart to concentrate on football,” Harlan told reporters of how Starr still had complete authority over football operations, including the selection of assistant coaches and player personnel. “Tom will handle the business end of the operation of the club [including ticket offices, accounting and facilities management] and I will handle the league matters and contract negotiations.”

Without a general manager or director of player personnel, Starr was responsible for the Packers’ 1981 draft. He drafted quarterback Rich Campbell with the sixth overall pick. “There is no question that I made a terrible mistake in passing on Joe Montana in 1979,” Starr admitted of his earlier decision to draft Charles Johnson instead, but “our selection of Rich Campbell over Ronnie Lott in 1981 was a colossal blunder.” During a forgettable career with the Packers, Campbell went on to throw a grand total of sixty-eight passes. Meanwhile, defensive back Ronnie Lott enjoyed a Hall of Fame career as a key contributor to the San Francisco 49ers championship teams during the decade. It was another personnel move that haunted Starr as the Packers’ fortunes continued to founder.

Green Bay’s 1981 season opener in Chicago began almost exactly as it had two years earlier. “For Eddie Lee Ivery, the similarities were too much to bear,” Starr recalled. “Once again, he got off to a fast start, and once again he found himself planting his left foot to make a sharp cut. He was on the same part of the field and his knee blew out once more, tearing a different ligament.”

Again, Ivery was done for the season, exposing the Packers’ lack of depth at running back. Following their 16–9 victory over the Bears, Green Bay lost their next two games. To reinvigorate the team’s offense, Starr traded three high draft choices to the Chargers for explosive wide receiver John Jefferson. The Packers stumbled to a 2–6 record at midseason before the offense exploded behind a healthy Lynn Dickey and the pass-catching trio of James Lofton, John Jefferson, and tight end Paul Coffman. “Sure enough, we won six of our last eight games and came within an eyelash of winning the Central Division title,” Starr said.

The Packers’ 1981 training camp was a popular destination for fans young and old, as players like James Lofton were popular with autograph seekers. (WISCONSIN STATE JOURNAL)

The overflow crowds at Packers training camp prompted several youngsters to use their bicycles to get a better view of practice. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

Wide receiver James Lofton (80) and quarterback Lynn Dickey (12) partook in one of the Packers most cherished training camp traditions: riding kids’ bikes from the practice field back to the Lambeau Field locker rooms. (WISCONSIN STATE JOURNAL)

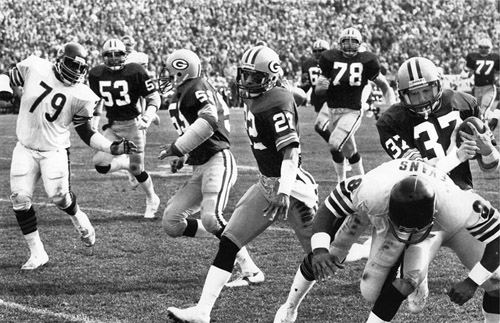

Packers safety Mark Murphy (37) anchored a defense that featured Mike Douglass (53), John Anderson (59), Mark Lee (22), Casey Merrill (78), and Mike Butler (77). (COURTESY OF GREEN BAY PRESS-GAZETTE FROM TOM PIGEON COLLECTION)

The Packers were within reach of a wild-card playoff spot heading into the season’s final week. If Starr’s squad beat the Jets and the Giants lost to the Cowboys that afternoon, Green Bay would make the playoffs for the first time in nine years. “A team doesn’t realize what getting into the playoffs means until it’s been there,” Starr said after the Packers’ 28–3 loss to the Jets eliminated them from playoff contention. “You talk and talk about it all season, but when it happens, it has a lasting effect on the team. It’s an invaluable experience.”

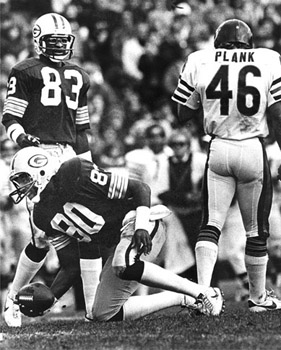

Kicker Jan Stenerud (10), photographed with holder and punter Dave Beverly (11), nailed twenty-two of twenty-four field goals in 1981 to rejuvenate the Packers’ lackluster kicking game after the departure of Chester Marcol. (COURTESY OF GREEN BAY PRESS-GAZETTE FROM TOM PIGEON COLLECTION)

The team’s improved 8–8 record did little to diffuse the issue of rehiring or dismissing Starr at season’s end. “I knew the pressures he felt when we just couldn’t get over the hump, and those pressures grew tremendously,” Harlan recalled. “The most important thing you do happens on Sunday afternoon when the whole world is there to grade you for three hours. If it doesn’t go well, eventually certain people are going to turn on you.”

After one of Starr’s strongest supporters, Dominic Olejniczak, announced he would step down as team president, the executive committee gave the head coach an unmistakable win-or-else mandate. “The Packer president, Robert Parins, a former circuit court judge, acted as though we hadn’t won a game all year,” Starr exclaimed of a growing fear that his days in Green Bay were numbered. “I had to work to get a mere two-year extension from him. I came away with an uneasy feeling.”

Convinced that the Packers were one impact player away from making the playoffs in 1981, Bart Starr made a rare midseason trade with the San Diego Chargers to acquire wide receiver John Jefferson (83), bolstering the team’s already explosive passing game that featured James Lofton (80). (WISCONSIN STATE JOURNAL)

• • •

Newly elected team president Judge Robert Parins expressed little patience for losing, reinforcing to the press that he had the power to “hire and fire the coach, or anybody else in the organization.” He also felt for the team to succeed, “the operation of this franchise clearly calls for a full-time executive officer. By that I mean someone who can take care of the day-to-day business.”

The full-time appointment was necessary. The Packers had become a multimillion-dollar corporation, part of a professional sports league that produced record television ratings in 1981 and was finishing up negotiations on a very lucrative television contract. The television networks were also profiting; a Time magazine article estimated that CBS made $25 million from the NFL alone in 1981. In March 1982 the NFL signed a then-record $2.1 billion television deal to remain with ABC, CBS, and NBC over the next five years. The 1982 deal was a dramatic increase, with each NFL team garnering on average almost $14.2 million per season, starting with $11.8 million in 1982, up from the $5.8 million per season they had been earning. For some owners, securing a profit was guaranteed before ever selling a single ticket or collecting money from parking or concessions.

The birth of modern franchise free agency occurred on May 7, 1982. The NFL lost a highly publicized lawsuit, which allowed the Oakland Raiders to relocate to Los Angeles. The impact of the court case would be felt throughout the decade, since the league was now unable to stop teams from relocating. “This only reinforced just how important Green Bay’s public ownership of the Packers had become. The team might have lagged in adapting to corporate-style management, but at least it would not be guided by the whims of a single owner,” author Don Gulbrandsen said of how unhappy owners could now threaten to abandon their home cities for greener pastures. “The saddest example of what NFL fans faced happened in the early morning hours of March 29, 1984, when Colts owner Robert Irsay ordered the team’s office and training facility equipment loaded into a convoy of moving vans and driven to Indianapolis.”

Four days after the Raiders’ relocation verdict, pro football made more headlines. Another rival league—the United States Football League—announced its formation and intention to start play the following season. From its inception, the USFL posed a greater threat to the NFL than the World Football League ever had. The new twelve-team league would play games in the spring, filling the football void between the Super Bowl and preseason games; it planned to lure disgruntled NFL players in search of better salaries; and it was well financed, securing a lucrative television contract with the emergence of cable television and its need for programming. ABC would pay the USFL $9 million for the broadcast rights to twenty-one games in the 1983 season. The deal also gave ABC the rights to the 1984 season at $9 million and network options for 1985 at $14 million and 1986 at $18 million. ESPN agreed to televise thirty-four games for $4 million and would pay $7 million for rights in 1984. These television contracts yielded approximately $1.2 million per USFL team in the first year. Understanding that the USFL had achieved instant economic stability through its two television contracts, the NFL recognized that the costs of being in the professional football business were about to rise in a similar fashion to when the league was in intense competition with the AFL.

The NFL’s 1982 season began with team owners and players engaged in a brewing civil war. The threat of a player walkout had loomed for some time. The current NFL Players Association contract had run out. With no agreement being reached, the NFLPA set a strike date. As in past disputes, the players demanded unrestricted free agency and increased salaries. The league had long fought the concept of one player leaving his team to join another, but NFL players now wanted to enjoy the same success baseball players achieved in their quest for free agency. In 1982 the average salary for an NFL player was $95,000, well below that of Major League Baseball players, who were earning $240,000 apiece, or the NBA’s players, who were taking home $215,000 each. “When I came into the league in 1978, a rookie could have signed a contract for $22,000, $26,000, $30,000 and $32,000 for his first four years,” wide receiver James Lofton, who also served as the Packers’ union representative, explained. “If you talk to guys like Jan Stenerud, when they came into the league, a lot of players were making only $10,000 to $12,000 a year.” The NFL of the 1980s would be expected to match its competition.

With the threat of a strike looming, the Packers poised themselves to make a serious run at the playoffs. In the 1982 season opener at Milwaukee County Stadium, they displayed their firepower with a spirited second-half comeback victory against the Rams. Their offense had found its stride, becoming as explosive as any in football, which fueled another come-from-behind win the following week against the Giants on Monday night. However, about a half hour before the game, while the Packers ate their pregame meal, the NFL Players Association announced it was going on strike at the conclusion of that evening’s game. “I think the strike actually started while the game was still being played, because it was a midnight deadline,” Lofton recalled of how the game had been delayed twice by mysterious power outages at Giants Stadium. “You think about the unions who were supporting the players, and you always wonder if they had something to do with it.”

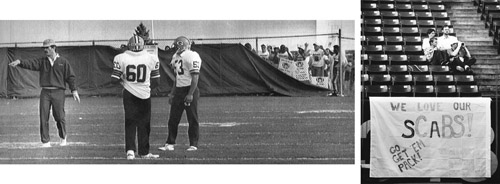

The Green Bay Packers’ locker room sat empty for fifty-seven days in 1982 as a players’ strike shortened the regular season to nine games. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

That night the NFL Players Association had invoked the first work stoppage that would result in the cancellation of regular-season games. For the next fifty-seven days, the nation went without professional football. The television networks, which had just signed a lucrative broadcast agreement with the league, put tremendous pressure on both warring factions to settle their dispute. In the meantime, NBC tried televising Canadian Football League games but couldn’t generate even a fraction of the audience from its NFL counterparts. When the players put on exhibition games to raise money for the union, the television networks refused to broadcast the contests, siding with league management. In an ironic twist, it was the lucrative television contracts that had galvanized the players, causing them to want a bigger percentage of the NFL’s revenue. In Green Bay, Packers officials kept a low profile during the players’ strike since the organization “always stayed in the background and tried to make the team the most important thing,” Lofton recalled.

The strike ended on November 16 when team owners ratified a new collective bargaining agreement that would run through the end of the 1986 season. The new contract guaranteed that owners would pay the players $1.6 billion over four years, including $60 million in immediate bonus money. The “money now” provision meant an increase in team payroll of about $2,250,000 to the Packers, as each active player was to be paid a minimum of $30,000 with a $10,000 increment added for each additional year of service. Other provisions of the CBA increased the minimum salaries from $22,000 to $30,000 for 1982, $40,000 in 1983, and an additional $10,000 per year for successive years of the contract.

In addition to the establishment of a minimum salary schedule, training camp, postseason pay, medical insurance, and retirement benefits were all increased. The players also gained several key concessions from the owners, including the right to obtain copies of every player contract and making salaries public knowledge, which allowed players—and their agents—more leverage in negotiations. A severance-pay system was introduced to aid in career transition, a first for professional sports. The owners, despite making numerous concessions, still considered the settlement a victory since there was still no complete system of unrestricted free agency. In reality, “as with any strike, both sides really were the losers,” executive committee member John Torinus remarked about how the eight-week strike cost players millions of dollars in unrecouped salaries and the owners an estimated $450 million in lost revenue.

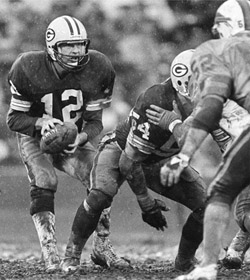

Behind a solid offensive line anchored by center Larry McCarren (54) and a potent passing attack from Lynn Dickey (12), the Packers finished with the NFC’s third best record in 1982. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

Besides the players and the league, the entire community of Green Bay was affected by the strike. Hotels, restaurants, department stores, and gas stations all suffered severe drops in sales as a result of three Packers games at Lambeau Field being canceled. Each game meant a loss of $1.3 million to area merchants, according to the Green Bay Area Visitor and Convention Bureau. So it was no surprise that the community showed little interest when the NFL scrapped the divisional playoff format in favor of a “Super Bowl Tournament” where the top eight teams from each conference earned playoff berths. The Packers finished the abbreviated season with a solid 5–3–1 record and would host their first playoff game in fifteen years. The fans, instead of expressing unconditional enthusiasm for the Packers, stayed away. For the first time since 1960, Lambeau Field wouldn’t host a sellout crowd.

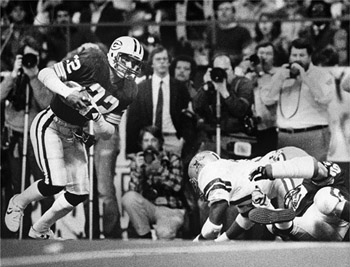

In 1982 Lambeau Field hosted its first playoff game since the 1967 Ice Bowl; the Packers polished off the Cardinals 41–16 behind two touchdowns from Eddie Lee Ivery (40). (WISCONSIN STATE JOURNAL)

In Dallas, safety Mark Lee (22) returned an interception for a touchdown in the second half, but the Packers couldn’t catch up to the Cowboys, losing by a final score of 37–26. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

The 54,282 fans that chose to support the third-seeded Packers were treated to an offensive showcase. Quarterback Lynn Dickey passed for 260 yards and hurled two touchdown passes to John Jefferson and one each to James Lofton and Eddie Lee Ivery in a thunderous 41–16 win against the sixth-seeded St. Louis Cardinals. The next week in Dallas, the Packers racked up 468 yards of offense, but Dickey’s three interceptions proved critical as Green Bay lost to the Cowboys 37–26. However, “the press universally declared that the Packers had won great respect in defeat, playing one of the best teams in the league toe-to-toe for sixty minutes,” Torinus said.

The NFL had survived the crippling effects of its players’ strike, but it continued to be under assault from the rival USFL. That spring, college superstar Herschel Walker and some other notable players spurned the senior circuit, signing lucrative contracts with the upstart league. When Walker and his New Jersey Generals debuted on March 6, 1983, against the Los Angeles Express on ABC, the USFL’s opening weekend was considered a success as it received strong television ratings and hosted an average of 39,170 fans in attendance per stadium. Although both of those figures soon declined, the modest successes the league enjoyed during its inaugural season only fueled more spending by its owners. The league’s original design for self-imposed fiscal discipline was soon abandoned as team salary structures began exceeding the $1.6 million-per-club limit. To combat the USFL’s player poaching, the NFL increased its roster size from forty-five to forty-nine players and began signing its own players to longer-term contracts.

The only significant player the Packers lost to the new league was defensive end Mike Butler. He bolted after Parins, who had taken over negotiating player contracts, failed to close on a new deal. With the Packers’ first-ever full-time executive taking a more active role in the team’s football operations, “there was a certain amount of power Bart lost,” quarterback David Whitehurst recalled. “From a player standpoint, the atmosphere was not as good. The situation in Green Bay changed.”

Judge Robert J. Parins made it clear who was running the Packers after he succeeded Dominic Olejniczak as team president. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

In March, when stockholders arrived for the Packers’ annual stockholders’ meeting, they were handed a mimeographed balance sheet. It showed the Packers suffering a net loss of $2,153,428 in 1982—not only the largest loss in team history but also its first since 1951. “This isn’t a happy report,” team treasurer John Stiles explained. The Packers lost ticket revenue from seven of the sixteen scheduled regular-season games canceled because of the strike, plus the corresponding television revenue. They also had to pay out $2.4 million to the players as part of the “money now” portion of the new collective bargaining agreement. “In spite of the losses we’ve had, we’re still in excellent financial position,” Stiles said. “We have short-term investments of more than $10 million and long-term investments of close to $5 million for a total of $15 million. We have every expectation that we’ll have a good, sound, prosperous year for 1983.”

When Starr took the podium, he was armed with statistical proof the Packers were poised to continue their winning ways. “We’re on our way up,” he told the crowd of 102 stockholders at the Midway Motor Lodge, citing the team’s 41 points in its playoff win against the Cardinals and the 466 yards gained on the Cowboys—both the most in the team’s postseason history. “It’s all coming together at a very good time for us.” Before he could return to his seat, Starr was applauded. The audience reaction prompted only a tight grin from Parins as he turned the microphone over to the nominating committee for further business.

Parins’s flippant reaction implied that Starr had used up almost all of the goodwill and fond memories he had accrued in his sixteen years as quarterback for the Packers. In the eight years since he had taken over for Dan Devine, Starr had guided the team to just one playoff berth and two winning records. In 1983 his task to return Green Bay to the playoffs was a sobering one. They were scheduled to face eight playoff teams from the year before on their regular-season schedule, but with all the pieces in place to return to the NFL’s elite, Starr explained later that the Packers “would have posted a winning record had we avoided a crippling series of injuries.”

In 1983, after the Packers’ first playoff appearance since 1972, Bart Starr and cohost Gary Knafelc, a former Packers wide receiver, had a devoted following for their weekly Bart Starr Show. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

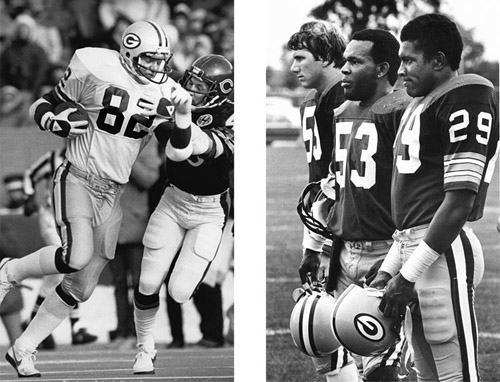

In 1983 tight end Paul Coffman (left, 82) and the Packers’ high-octane offense tried outrunning their opponents by generating 6,172 yards, 52 touchdowns, and 429 points. But Green Bay’s defense was just as vulnerable, allowing 6,403 yards, 50 touchdowns, and 439 points despite the solid efforts of (right) John Anderson (59), Mike Douglass (53), and Mike McCoy (29). (LEFT: MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL; RIGHT: WISCONSIN STATE JOURNAL)

Green Bay hovered around .500 all season, never winning or losing more than two consecutive games. In one four-game stretch, the Packers posted an almost perfect 55–14 win over the Buccaneers in week five, only to be humbled by the Lions the next week, followed up with an epic Monday night victory over the defending Super Bowl champion Redskins, and then an overtime loss to the Vikings. All season, the team suffered through wild fluctuations from game to game, from quarter to quarter, and sometimes from play to play. Starr would later admit, “Our sixteen-game roller coaster was not the best Packer team I ever played for or coached, but it was by far the most exciting.”

As part of one of the most fearsome offenses in the league, quarterback Lynn Dickey threw for an astounding 4,458 yards in 1983 as four receivers—Lofton, Jefferson, Coffman, and Gerry Ellis—each caught at least fifty passes. The Packers’ 6,172 yards of total offense set a team record on the way to 429 points. But Starr’s league-worst defensive squad surrendered a gluttonous 439 points, holding teams to fewer than 20 points only twice all season. Despite Green Bay’s inability to stop anybody on defense, they still had a shot at the playoffs if they could win their season finale against the Bears.

Hosted at Chicago’s Soldier Field, the game meant more to the Packers, but the Bears reveled in their role as spoilers. In a contest that seesawed back and forth, Green Bay took a late 21–20 lead with only a few minutes left. As Chicago responded by marching downfield, Starr refused to use any of his available timeouts. With just ten seconds left, the Bears kicked the game-winning 22-yard field goal. The Packers had no time to respond when they got the ball back and suffered the 23–21 loss. Afterward, “I never saw Bart more discouraged,” Harlan recalled. “His disappointment was simply that we were right on the verge of getting to the playoffs, and we didn’t do it.”

The agonizing defeat, which left the Packers with an 8–8 record, eliminated them from the postseason for 1983. Nevertheless, Starr felt good about the direction the Packers were headed. They were four seasons removed from their last losing campaign, showcasing a potent offense. If the defense could get healthy, the team would be on the brink of becoming a consistent contender. “We were no longer a losing ball club, and, more important, we were on the verge of long-term respectability,” Starr remarked. “We had rekindled the emotions between the Packer fans and the team. We played exciting, hard-hitting football, and we did so with class.”

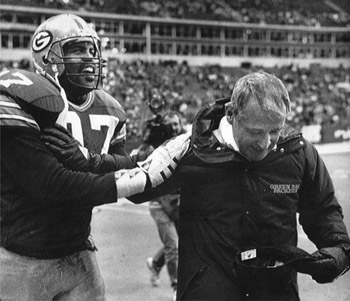

Less than twenty-four hours after the loss in Chicago, “Starr said that Parins came into his office and said rather bluntly, ‘Bart, you are relieved of your duties as head coach.’ Parins then turned and walked out, according to Starr, who closed his door, buried his head in his hands and let the emotions of nine losing seasons pour out,” trainer Domenic Gentile recalled. “There is no good way to fire a man, but Bart deserved better than that cold slap in the face.”

After nine years as head coach, Bart Starr was fired following the 1983 season with an overall 53–77–3 record that included two winning seasons. (WISCONSIN STATE JOURNAL)

“He didn’t thank me for my efforts, didn’t say a word about my twenty-six-year contribution to the Green Bay Packer organization,” Starr recounted. “He didn’t even express any regret about having to make the decision. He sounded as though he were delivering a cold, unemotional sentence in his circuit court.”

Although Starr had dedicated his life to the Packers, “it is difficult … to argue with Judge Parins’s decision. Starr did go 21–19–1 in his last three seasons, but it took six bleak seasons to put together that modest run,” author David Claerbaut recounted in Bart Starr: When Leadership Mattered. “Starr really had only one good year, the strike-shortened ’82 season when the team ranked tenth on offense and eighth on defense. In no other season did the team rank in the upper half of the league on both sides of the ball.”

When announcing Starr’s dismissal to reporters, Parins said the decision was “not made out of emotion or frustration, but on an overall evaluation of the needs of the franchise; we feel the position of head coach needed a fresh look,” and while several factors came into play, “if we had had a winning season, in terms of the playoffs, we would not be having this session today.”

Only moments after Starr was fired, the Packers put together an informal list of almost twenty-five candidates for the job—some whom the team was interested in approaching and some who had contacted the team. The organization felt its next coach had to be a disciplinarian and a taskmaster. The executive committee anticipated a long, drawn-out process, one that could allow for a clean break from the team’s past and forge a new identity independent of the Vince Lombardi era. At the same time, they couldn’t resist the idea of having another one of Lombardi’s disciples lead the team. On Tuesday morning, Parins read in a newspaper article that Forrest Gregg was interested in the Packers job but still had two years remaining on his contract as head coach of the Bengals. The Packers contacted Cincinnati and on Wednesday received permission to speak to Gregg. In explaining his haste, Parins said he felt that “this matter involving Forrest came up quite suddenly and in a manner that required us to move rather quickly if we were going to have a satisfactory attempt to offer him this job.”

On Thursday Parins discussed the possibility of Gregg as the team’s next head coach with the Packers’ seven-man executive committee. The next day, Parins and Gregg met in Chicago. Parins would later admit, “He was the only person that we offered the job to.”

On Saturday, Forrest Gregg was introduced as the Packers ninth coach in franchise history. “I don’t think I would have left Cincinnati for any other job. Ever since I left Green Bay, I always hoped that some day I’d get the opportunity to coach this football team,” Gregg told reporters during the introductory conference call. “I spent fourteen years in Green Bay as a player. If I was looking for a college coaching job, I would want to go back to SMU where I played—that’s where my roots are. This is where my roots are as a professional football player.”

The Packers’ executive committee felt Gregg was the perfect person to restore order and the tradition of winning football in Green Bay. “People in the office were sad when Bart left, but Forrest was another Vince Lombardi hero coming home, and so he was very welcome,” Harlan recalled. “And it looked like a coup when he came here.”

For the first time in team history, the Packers had hired a head coach with previous NFL head coaching experience. Gregg had coached the Cleveland Browns for three years and also led the Bengals to a Super Bowl during his four seasons in Cincinnati. He had earned a reputation as a stern disciplinarian, which was showcased during that initial conference call. “I believe in discipline,” Gregg told reporters. “I don’t think there’s any question it’s one of the most important things to a football team. The players have to understand what is expected of them.”

New Packers head coach Forrest Gregg (with arm raised) returned to Green Bay with expectations of leading the Packers—including Dave Drechsler (61) and Larry McCarren (54)—back to the playoffs. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

After Parins proclaimed to reporters huddled around the phone at team headquarters that “Forrest will have full responsibility of the football operation,” Gregg commented, “From the outside I thought I was inheriting a good situation with the Packers.”

From the moment he arrived in Green Bay, Gregg decided his training-camp two-a-day practices exposed an inherent weakness. “If I could put my finger on one thing that this team needs,” he said of his belief in the full-pad, full-contact practices that players considered pure torture, “this team is really not very strong physically. And that hurts you in two ways—it hurts in consistency and it also makes you more susceptible to injury.”

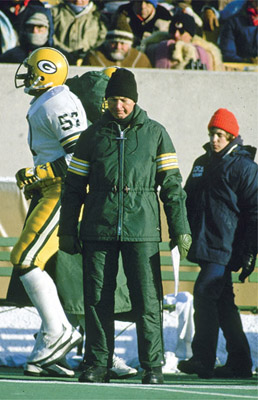

Forrest Gregg (left) and offensive coordinator Bob Schnelker (wearing glasses) had a brewing quarterback controversy in 1984 as rookie Randy Wright (16) and former first-round draft pick Rich Campbell (19) threatened to take the starter’s role away from the often-injured veteran Lynn Dickey (far right). (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

The team was slow to adapt to Gregg’s changes and finished the first half of the 1984 season with a lone victory. His decision to trade kicker Jan Stenerud to Minnesota during the offseason was “a move that probably cost us at least one ball game,” he later admitted after the Packers lost a 17–14 game to the Broncos in Denver where kicker Eddie Garcia missed three short field goals. “Trading Jan was a move I lamented, one that might have been the difference between us making the playoffs and staying home for the holidays.”

During one stretch of heartbreaking defeats, a reporter asked Gregg if he was worried about his players’ morale. “I’ll never forget his answer,” trainer Domenic Gentile remembered: “ ‘Their morale? I’m not worried about their morale. They’d better be worried about mine.’ ”

When everything started to click, “winning seven of our last eight games was a mixed blessing,” Gregg recalled of the Packers’ 8–8 finish. “We came very close to the playoffs, but the ’84 Packers were an old team. Changes were necessary. We needed to revamp the roster and make the club younger. But I was lulled by the chance to reach the postseason. And I also knew there would have been serious fan repercussions had we torn the team apart after that great finish. So we sat pat and made no major roster changes leading into the 1985 season.”

• • •

Before the start of the NFL’s 1985 season, the USFL found itself imploding. The upstart league continued to poach NFL rosters, forcing the escalation of salaries. It also signed some of college football’s best players—including Doug Flutie, Jim Kelly, Steve Young, and Reggie White—to lucrative contracts that exceeded the league’s revenue streams. Back in 1984, when the USFL had expanded from twelve to eighteen teams, it experienced a decline in television ratings. However, spring football was still sought after by television networks as ABC exercised its option to broadcast the league in the spring of 1985 and even offered a $175 million contract for four additional years beginning in the spring of 1986. ESPN also wanted to stay in business with the USFL, offering a contract worth $70 million over three years. The young league’s future looked promising, but its continual straying from the original mission of fiscally responsible, year-round football had taken its toll. On August 27, 1984, the USFL owners—under the urging of New Jersey Generals owner Donald Trump—voted unanimously that after the 1985 spring season the league would resume play in the fall of 1986. The USFL then filed an antitrust lawsuit against the NFL, in hopes of forcing a merger, seeking damages of $1.69 billion and further claiming the NFL was monopolizing the television revenues and creating the inability for the USFL to negotiate a television contract for a fall season. With its lawsuit against the NFL pending, the USFL would suffer through a tumultuous third year.

When the USFL kicked off its third season, the league had contracted to fourteen teams. Several franchises had relocated or suspended operations, knowing they couldn’t compete head to head against their counterparts in established NFL cities. Television ratings continued to decline as the league spiraled into greater fiscal and legal turmoil. After the 1985 spring season, franchises continued to merge, relocate, and fold. In 1986 only eight USFL teams remained as the league awaited commencement of its antitrust lawsuit against the NFL. The USFL’s survival now rested on the trial’s outcome. Following twelve weeks of testimony, the federal court jury rendered the verdict that the NFL was guilty of only one of the minor counts of antitrust violation and awarded the USFL one dollar in damages, tripled to three dollars because it was an antitrust violation. Although the jury found that the NFL’s unlawful monopolization of the professional football market had injured the USFL, it cited ample evidence that the USFL had engaged in behavior that contributed to its own demise. The new league’s own shortcomings, rather than intentional behavior on the part of the NFL, had caused it to fail because it didn’t make the necessary investments and demonstrate the required patience to create a stable and credible professional sports league.

Following the verdict, the USFL suspended operations and never played again. In three short years, it had fielded teams in twenty-two cities with thirty-nine principal owners and amassed fiscal losses estimated at $200 million. Although the NFL was no longer in direct competition with the league, it continued to feel its effects. Besides being the first to use instant replay to challenge officials’ calls and instituting professional football’s first two-point conversion, the USFL had forced the escalation of NFL salaries. Prior to the USFL, NFL salaries were increasing at a rate of approximately 7 to 10 percent per year. During the first two years of the USFL, NFL salaries jumped 25 percent; they increased another 19 percent in the third season. After the USFL folded, NFL salaries reached a plateau, rising only 5 percent in subsequent years. The USFL’s legacy would continue to have an impact over the next decade as well, as many of its players and coaches found success in the NFL.

Meanwhile, the Packers were overseeing the first major upgrade to Lambeau Field since 1970. While earlier expansions had increased the stadium’s capacity to 56,263, the facility lacked the moneymaking luxury boxes that had become commonplace in so many other NFL venues. At the start of the 1985 season, the Packers rectified the situation with the debut of seventy-two private suites, increasing the stadium’s capacity to 56,926. If the Packers were going to stay competitive in the new world order of generating revenue, the luxury boxes were a good start. For almost two decades, the Packers had survived thanks to the mystique of Lombardi and a devoted fan base determined not to give up on its franchise. Lambeau Field continued to host sellout crowds and maintain a waiting list for season tickets in the tens of thousands, but that patience and dedication came with a price: high expectations.

As the 1985 season approached, optimism prevailed throughout Green Bay. “I’ll just say this—this team has been close for several years now, but they’ve always been that one game away,” Gregg said, referring largely to the Packers’ 7–1 second-half run to finish at 8–8 for the second consecutive season. “We’re going to have to close that gap. A lot of times, that one step is a tough step to take.”

When Forrest Gregg decided to overhaul the Packers’ roster with younger talent, several veterans, including Eddie Lee Ivery (40) and Lynn Dickey (12), found themselves on the sidelines alongside longtime Packers photographer Vernon Biever. (WISCONSIN STATE JOURNAL)

Although Gregg had a fiery coaching style compared to the studious Devine and more reserved Starr, his old-school demeanor seemed to only echo the success of his mentor, Vince Lombardi, who still cast a shadow over Green Bay—one that nobody could seem to outrun. The legend of Lombardi was still very much alive in Green Bay. His moving speeches could be heard at the Packers Hall of Fame. His name was plastered all over town: Lombardi Avenue, Lombardi Plaza, Lombardi Middle School. His spirit seemed to pace the Lambeau Field sidelines alongside his failed successors, only fueling further comparisons. “There are paper mills scattered all about Green Bay, a city of fewer than 90,000 people,” Washington Post columnist Gary Pomerantz wrote. “It’s a good thing, too, since you need pages and pages to chronicle the Packers’ post-Lombardi failures.”

Nothing irritated current Packers players more than hearing about Green Bay’s storied past. How often were players hearing the name Lombardi brought up in Green Bay? “After every loss,” offensive lineman Tim Huffman said, noting his growing frustration. “The man’s been dead for fifteen years, right? I haven’t noticed him performing any miracles over the past fifteen years, so he must have been human, right?”

As the losses continued to mount during the 1985 season, “even Forrest said he was tired of hearing the name Lombardi,” offensive tackle Greg Koch, who was a nine-year veteran in Green Bay, told the Milwaukee Sentinel. “The worst thing is, we’ve had the players here over the years. We just haven’t done anything with them.”

After one particularly embarrassing loss, a frustrated Forrest Gregg kicked a garbage can full of ice and soft drinks that sat in the center of the locker room. Because it was full of melting ice, it didn’t budge. “You knew it had to hurt,” rookie linebacker Brian Noble recalled. When several players stifled laughs, Gregg turned to linebacker Mike Douglass and chastised him in front of the other players for what he considered especially poor play. When Douglass yelled back, the argument escalated into a free-for-all with soda cans and bodies flying back and forth until order was restored. “I was stunned,” Noble said as players stood around afterward in quiet shock. “I just put my head down and said, ‘This is hell.’ ”

Meanwhile, the Bears were steamrolling through the regular season en route to their first Super Bowl victory. Chicago’s recent success and the Packers’ continued failures found their rivalry becoming downright nasty. “During my tenure as coach, the rivalry heated up, to put it kindly,” said Gregg of the Bears. “But what stoked the rivalry from my point of view was simply the desire to defeat Chicago. They were the team to beat in the NFC Central, and the 1985 edition of the Bears were the measuring stick for the entire league.”

Regardless of whether it stemmed from when the two coaches—the Bears’ Mike Ditka and the Packers’ Gregg—had collided back when they were players, or because of current personality clashes, their games during the mid-1980s were some of the ugliest ever played. “I don’t think the rivalry was ever as full of antics as it was in that period,” Noble remarked about how the exchanging of insults and cheap shots before, during, and after plays only seemed to escalate in front of a national television audience. During a Monday Night Football game in Soldier Field, Ditka called for his 320-pound defensive tackle, William “Refrigerator” Perry, to line up at tailback, take a handoff, and plow over linebacker George Cumby for a one-yard touchdown that added insult to an already embarrassing 23–7 Packers loss.

Despite all of their early season disappointments, the Packers won five of their last seven games to finish 8–8 for the third consecutive season but again fell short of the postseason. “It’s been that way for us for years,” defensive end Ezra Johnson said, noting how injuries continued to plague the team’s playoff aspirations. “The bug comes up and bites us.” It was a bug that coach Forrest Gregg planned to eradicate that offseason.

• • •

During the Packers’ 1986 training camp, Forrest Gregg was asked what it would take for the Packers to make the playoffs. “Winning another game or two,” he replied with a chuckle before providing a more calculated answer. “We’ve got to get off to a better start and we’ve got to play consistently well all year long.”

In reality he felt that “after two years of mediocrity with an old team, I was tired of sitting still,” choosing to replace many of the Packers’ experienced veterans with younger players. “Our 7–1 finish in the ’84 season had raised expectations for the following year, and had we dismantled the team at that point, I might have been run out of town, but waiting a year to do it was a mistake.”

Gregg’s overhauling of the roster saw several beloved stars, including Paul Coffman, Mike Douglass, and Lynn Dickey, no longer wearing green and gold. By the start of the 1986 season, only eleven players remained from the fifty-seven Gregg had inherited two years earlier. “What I’m trying to do with this football team is to get a fresh start,” Gregg told reporters. “We have a lot of inexperience, but we are willing to take the risk. I felt like if we were going to move forward, we had to take some calculated risk.”

Members of the Packers took part in the fabled nutcracker drill during training camp in 1986, a technique made famous in Green Bay by Vince Lombardi and reintroduced by Forrest Gregg. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

Relying on younger, less experienced replacements, Green Bay suffered its worst start in franchise history, going winless in its first six games and causing a frustrated fan base to lash out. “When the Extremely Honorable Robert J. Parins hired Gregg as the main man,” Milwaukee Journal sportswriter Michael Bauman observed, “everyone agreed that Forrest would fix everything. And so far this year, he has—for the Houston Oilers, for the New Orleans Saints and for the Minnesota Vikings. The Chicago Bears are not on this list because they did not need assistance.”

The losses piled up as injuries to key players—including offensive lineman Rich Moran, linebacker John Anderson, and cornerback Tim Lewis, who suffered a career-ending neck injury—exposed the team’s lack of depth and experience. The Packers’ mistake-prone offense struggled to score points. They shuffled through a quarterback merry-go-round of Randy Wright, Vince Ferragamo, and Chuck Fusina while showing interest in upgrading the position. “So the Green Bay Packers have been trying out quarterbacks,” Bauman exclaimed after the team failed to acquire the Rams’ Jim Everett and Patriots’ Doug Flutie. “What they should be holding tryouts for are general managers. The mistakes being made by this particular organization transcend any one particular playing position and go to the nature of the organization itself. The management in Green Bay could qualify for the Olympics because, of course, the Packers brass still has amateur status.”

The Packers were also earning a reputation around the league for playing dirty. The worst infraction occurred during a November 23 game in Chicago. “I hated to see us resort to late hits and cheap shots,” trainer Domenic Gentile remarked. “Charles Martin’s infamous body-slam of quarterback Jim McMahon a full three seconds after the whistle blew was an embarrassment.”

The incident, which was witnessed by a large television audience and repeated infinite times in highlight packages broadcast across the country, showed Packers defensive end Charles Martin slamming McMahon into the ground after throwing an interception. The egregious late hit ended McMahon’s season with an injured shoulder and got Martin ejected from the game and suspended for two more. Adding to the controversy was that Martin was wearing a hand towel listing the numbers of several Bears offensive players, which he allegedly bragged was a hit list. Afterward, when Ditka accused the Packers of being thugs, Gregg remarked, “I don’t think it was a coincidence that the only time we were accused of playing dirty was when we played Chicago. I apologize for nothing… . We were out there trying to win and what we did was play the Bears the way the Bears played us.”

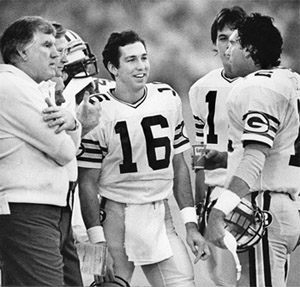

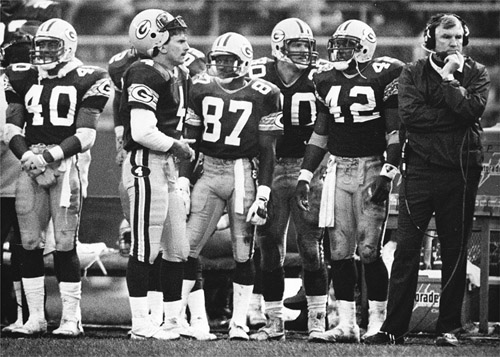

Forrest Gregg (far right) started looking elsewhere for answers as the Packers, including Eddie Lee Ivery (40), Ben Thomas (92), Chuck Fusina (4), Walter Stanley (87), Paul Ott Carruth (30), and Gary Ellerson (42), failed to make the playoffs in 1986. (MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL)

During a 4–12 campaign that couldn’t end soon enough, several off-the-field indiscretions further soiled the organization’s reputation. “Overshadowing our dismal performance was a seemingly endless flood of arrests, accusations, and bad press that would mar the remainder of my stay in Green Bay,” Gregg recalled. “For Packer players, life in Green Bay was like living in a fishbowl. And for a period of time it seemed as if everything that could happen did happen. A number of my players ran into trouble with the law for a variety of transgressions.”