December 10

The baby is almost two months old. Life here has fallen into a rough routine. Arno works at the typewriter during the day from about noon till six, often handing me the just-finished manuscript pages over the baby’s head as he nurses. We discuss the characters as though they were intimate friends. They seem to live here with us, although, of course, they have residences and lives of their own.

“Then what is Mark going to do?” I’ll ask. (Mark is the main character.)

“Don’t ask me,” says Arno joking, but half-meaning it. “He may go to Europe.”

The source of his gift remains mysterious to him as well as to me. We refer to the source as The Troll, will say he’s dormant lately, or turning over and grunting, or sometimes in full steam sending up ten different sparks at a time (when Arno has worked simultaneously on a poem, an article, his journal, a story, and the novel), the image being some gnome-like creature banging away at an anvil in a cellar.

Afternoons, I leave him working and wheel the baby to Kolonaki Square; come back, shop for groceries or the peppery souvlaki for dinner, and the typing stops. The sharp staccato of his typing is a steady accompaniment to our daytime lives; its speed and accuracy seem to express perfectly the efficiency, single-mindedness, and discipline of his work life that I admire wholeheartedly but can’t myself achieve. We eat, and then it is time for Joshua’s bath on the coffee table in the round, yellow tub, and the final nursing. I must spend six hours of the day with the baby at the breast.

By then it is eight or nine, and Arno usually leaves for the Plaka or to walk, ending up at some café, scribbling on napkins. He has made a few friends, whom we badly need, and these he sometimes asks home for me to meet.

The evenings have their own nature and belong to me. The apartment is semi-dark, except for one light in the bedroom or bathroom. Often lately, Joshua can’t fall asleep and, after I’ve rocked him, nursed him again, sung to him, and I still can’t get him comfortable, I finally have to leave him in his crib to cry awhile. I can’t stand to hear the crying, so I turn on the water full-force in the bathtub and wash the day’s dozen diapers, sheets, shirts, and our own clothes. The running water will usually just cover the bleating cry.

Transfiguration of excrement. When you become a mother, all of life transforms. I have seen on Arno’s face a combination of pain, revulsion, and anger watching me, once or twice, as I stood laughing, my robe running with the baby’s spit-up milk and the contents of a leaky diaper.

I thought: “Oh, you are still thinking of it in the old terms.” When you are a mother and it’s your baby, those just don’t hold any more. What slides down the drain in the yellow water, what I see in the diapers is a mixture of him and me. I wash away the curds of my own milk and try not to hear his sobs which cut under the pouring water and into my gut.

Sometimes, when I have tried very hard to make him comfortable and get nowhere, I become furious, want to shake him, even hit him. Sometimes I do shake him or rock him too violently in the carriage. Then I am ashamed of my temper and lack of control and feel guilty.

Often it happens when I have just put him back in his crib around two in the morning and count on at least three hours of sleep for myself before the next feeding—and an hour later I hear him crying with colic in the next room.

He is a very big, muscular baby and his appetite seems insatiable. At two-and-a-half months he is still nursing about every three or four hours around the clock. His demands on me, both physical and emotional, are so great that I need his sleeping periods as much as he does, so that I can greet him with eagerness and affection at the next meeting.

Once in a while, when I have been counting on a rest from him and he won’t sleep, there are flashes, not just of anger, but resentment and actual hate. I find I’m okay as long as I let the true intensity of feeling come through (to myself, if not to him). If I let myself really feel the resentment and even the hate, it soon passes off, permitting my love to flow back swiftly on the next psychic wave; whereas, if I stifle my anger, I feel cold and rejecting toward him for hours.

December 12

As I tiptoe past the crib on the way to the kitchen, I am once again—as I’ve been a hundred times—struck by the beauty of the shape of his head.

“If he never got any hair he’d still be beautiful,” I think. “But you’d have to have a mother’s eye to appreciate it, probably” (I add out of fairness but not truly believing it).

The mouth makes a sucking movement, he stirs, and I go on to heat the water for our nightly camomile. Although I was told to give it to Joshua, we have taken to drinking it ourselves, as do most of the Greeks, at least the aging ones. It is a beautiful tranquilizer and soporific. Also good, supposedly, for soothing the stomach. It cheers and relaxes us both, and I love the tiny flowers and stems that lay swirling gently in the bottom of the cup, wet and golden. Its sweetness and warmth is part of the nightly ritual. The scent of the camomile flowers is haunting—it reminds us of something and neither of us can place it.

We drink it lying on the Spartan Athenian Couch, our miserably uncomfortable bed which is composed of two cots, placed together, one considerably higher than the other. In fonder moments, I think of it as a split-level pallet, which thanks to the power of language gives it a certain tone in my mind.

At two in the morning, uncomfortable and unable to huddle because of the precipice between us, freezing with cold, as winter has set in, teeth chattering, hearing loud snatches of a drunken song outside our windows from stragglers returning from the tavernas—we lie and talk.

Last night, I finally spoke about something that had been bothering me for a very long time.

“Do you realize, Arno, that the word ‘people’ is disappearing from the news media altogether? I haven’t seen it in the Times or magazines in—since I don’t remember when. It’s a shame and I miss it. Now everything is ‘persons.’”

It was beginning to take on the proportions of a conspiracy in my head. “They” had taken a perfectly good, useful, friendly word and knocked it out of the language. But why? Who would want to do such a thing? It was no longer used except in its formal meaning as in “The peoples of the world,” never for just plain folks.

“Listen,” said Arno. “Substitute: ‘The Persons, Yes.’ ‘Persons are Funny.’ ‘Of the persons, by the persons, for the persons.’ ‘Just plain persons.’ ‘You can fool some of the persons, some of the time.’”74

And on and on. One thing led to another and when Joshua woke for a 3:00 A.M. feeding, we had just created a new creature called the Jeopard and its native country, Jeopardy—not far from its neighbors Picardy, Lombardy, Drunkardy, Slovenly, and Bastardy.

December 13

Late. And cold. It’s after 2:00 A.M. and I’ve just put the baby back in his crib.

I know Arno is off making the social contacts we need to survive and getting a breather from his long grind at the typewriter, but I must admit I resent his going out almost every night. I haven’t spoken to him of my resentment. Am I still feeling too guilty over making a father of him to let it out? Or is that an excuse to avoid conflict?

One day he brought home a Wellesley dropout on her way to India. She simply had—she said in her Wellesley accent—to smell the flowers in the Himalayas (which she pronounced to rhyme with dahlias). Deep from my bleary-eyed maternity, I looked at her unbelieving, intolerant, although, come to think of it, our own reason for being here isn’t that much more solid.75

He did better when he brought blond Costis—a painter—and his wife, Gella. He had met them and about half-a-dozen other people to whom he enjoyed talking, at a place called the Nine Muses in the Plaka. We left Costis’ sister-in-law to babysit, and he took me there one evening. It was another world: carpeting, dim lights, benches, and low coffee tables around which sat sleek, intelligent, beautiful women, and men with interesting faces, sipping coffees, brandies. There was music—the haunting, sentimental melodies of Hadjidakis, the cauterizing music of Theodorakis.76 At the Nine Muses in Athens a rare thing was happening: men and women were talking to one another.

People I had never seen came up and greeted Arno, who was obviously a regular. They laughed together and gossiped, picking up conversations whose beginnings I had missed, last week, last month.

Oh. There he is. I hear whistling in the hall. Dinos, he says, was showing some poems he had written.

December 14

I went to the drugstore tonight to get the diaphragm for which Madame Kladaki had so magically fitted me. I told the druggist a size, and he turned to a pile of pessaries lying randomly on the counter in back of him. They appeared to be samples. He started to wrap one for me.

I asked, God knows how, if he had any spermicide—any kind of medication to go with it. He looked at me with puzzlement and turned to his woman assistant.

“Cream?” I asked. They looked amazed and shrugged, suppressing smiles. No. They had never heard of any such thing! Now, thinking back, I wonder if they thought I wanted to eat it.

“Never mind wrapping it,” I said. “I won’t take it now.” I looked around the store. “Do you have saccharine?” I asked. Arno had wanted some for his coffee and the camomile tea. Two men came in and pushed me gently but firmly out of the way, stepping up so they could talk to the druggist. It was ten minutes before I could finish my business with him.

I crossed Kolonaki Square in the cold dark and turned into Karneadou Street, a little dazed. As I neared the apartment, I could see Arno through the window; three coffee cups were on the desk and a cigarette burned unclaimed in the ashtray; his strong, dark head was bent over his work, and his typing was so rapid and expert it sounded like machine-gun fire in the hallway.

I walked into the apartment humming a chorus of Hopa nina nai, and he looked up from the typewriter expectantly.

“Well? I hear the song—I’ll bet you didn’t get it. I thought you wouldn’t be able to get a diaphragm without a written prescription from Madame Kladaki!”

“Arno,” I said gently. “I could have gotten ten diaphragms, and probably all the wrong size—they were lying around like cough drops. It was the saccharine I couldn’t get. They absolutely refused to sell it to me without a written prescription.”

“It may be a question of values,” I said, as he turned back to the typewriter.

“Excuse me,” he said simply, “I’ve got culture shock.”

December 15, Afternoon

Is it irrational? Am I lacking some maternal feeling that I am only relieved that Joshua is quietly sleeping? It would never occur to me to check to see if he breathes (and possibly wake him in the process).

Why do many parents look to see if a baby breathes? Frieda was terrified that if Josh lay on his stomach he wouldn’t be able to breathe, but a number of American parents I have known seem rather morbidly driven to peek in on a baby, “just to see if he’s breathing all right.” What if they spoke it more plainly: “Oh, I just want to look in to see if the baby is alive.” It is bald, shocking. Worse yet: “I’m afraid the baby might be dead.” And I think that may be the real motivation behind the frequent checking. I’m convinced it isn’t because of the rather rare crib death, but, instead, some lack of faith in the strength of the child’s grip on life—perhaps a disguised questioning of the strength of one’s own transmitted life-force.

Our myths about babies come from watching several generations of those born drugged with the mother’s anesthetic. As I was growing up I saw, almost exclusively, babies born “naturally.” The couple of babies I have known who were born of anesthetized mothers were completely different. They seemed, by comparison, dazed, dopey, unsure they wanted to participate in the whole business of being alive in this world. They had none of the wide-eyed expectancy and brightness of the natural ones—or the good humor. It is easy to understand why people, seeing a couple of generations of these children, say that babies don’t see well, or only want to sleep, or are unaware.

I have a feeling of completion these days unknown to me before in my life. I am like someone who, never having had quite enough to eat, finally knows what it is to feel full. But instead of dulling them, the fullness stimulates other appetites. I feel a release of all creative powers. I am beginning to write a magazine article and I’m working differently, and with a new discipline. It is as though the big job is done, and now it is possible to go on about one’s life. I am doing what I came to do—the prolonged girlhood is finally over.

Joyousness in simply breathing out and in.

December 16

Sometimes when the writing doesn’t go smoothly, Arno dictates to me. Yesterday, he dictated while I typed, a very funny new chapter in which Mark and his girlfriend, Madeleine, try to act out their sexual fantasies with each other. Otherwise, a long Sunday. We are trying to talk Costis into coming to the States. Our Balkan babysitter, Francisca, who is Costis’s sister-in-law, hasn’t shown up for the third time, and we haven’t gone out in nearly two weeks. I think she left home. She is writing a book, she says. She told us how she would have to pay to have it published, as authors here normally do pay to see their work in print, rather than the other way around.

Like her sister, Gella (Costis’ wife), she has the same beautifully petulant mouth. The most interesting feature of her face, perhaps, is the great pouting lower lip which she, like Gella, pulls out and down when she speaks. Arno and I have spent hours trying to imitate the way she says “of course.” It is absolutely original. Blond Costis with his English accent (“Boolsheet! I say Boolsheet to soch seely pearsons”) has told us that if he shows his paintings in some galleries that are willing to give him an exhibit, he would be fired from his job. Gella, who was married and divorced from her first husband, an Athenian, in Arizona, tells us what the Greek men are really saying when they talk to women on the street. “He told me I was beeootifol. He said he wanted to fock me.” And she pouts and tosses her blond hair and plays with her delicate, dark-blue worry beads like a horny nun. We spoke with Gella about it at length. I have gotten so I detest walking around the streets. Because I am foreign, I am automatically considered likely to be a whore. They follow me and talk to me—as they do with other foreign women and some Greek women. One evening, out on an errand, I was walking in the rain. Suddenly, I felt something on my leg. It was the point of an umbrella held against my shin. I felt, rather than saw, the presence at my side. The man’s voice went on and on, and he walked with me with the umbrella just touching my leg. I looked neither left nor right, but walked as he talked. After three blocks, he crossed the street and I saw a finely dressed, middle-aged man. This kind of thing—sans the half-comical, half-sinister umbrella—happens at least three times a day. And you can never pass by a man without reading his thoughts. The American man imagines. The Greek assumes it’s really possible, even likely. One evening, I was standing looking at a poster advertising a movie. A short man with a moustache watched me. I glanced at him and looked back at the poster. Then I walked home. After a block or two, I felt as if I were being followed but walked on until I was near our apartment. To check, I turned my head for an instant. The moustache was indeed several feet in back of me. I turned into the apartment and could see him searching for the bell! (Hustlers here often live in the plusher buildings, give a single name on the bell, or have a special little light.) He was still there five minutes later, certain that because I had turned around I was giving him an invitation. Arno finally threw open the window and shouted at him and he disappeared.

Costis tells us that men not only tell pretty girls they are pretty and that they want to “fock” them, but they often make a special point of telling a homely girl just how homely she is. It is a fact of Athenian middle-class life that there are summer widows—the wives of men who spend the tourist months around Constitution Square to pick up the English, Scandinavian, Dutch, and American women who are the special prey of the Athenian man.77 They are special to him for the same reasons the Greek man may have a special charm for her. She is Northern. He is (in her mind) Southern. He must, therefore, be passionate and free. She (he thinks) is from the North, where life is freer. Not so many rules and prohibitions. She is sexually more willing and responsive. More passionate, in short, than the Greek women. Mostly, she is more accessible. She can even be talked to. Greek men, especially the young ones, complain that no man can talk to a Greek woman. They are interested in clothes and money and small talk and not in understanding a man, nor in sex. From what Costis tells us, and the new friends that Arno is meeting at the Nine Muses, we gather that “it is a miracle almost beyond belief if a Greek girl moves her hips in bed,” and that even among the Greek equivalent of the dolce vita crowd, it is hardly unusual for a girl to go to bed with her lover while moaning “it’s a sin, it’s a sin.” But how could things be much different? A Greek girl is raised from the first moment to be a second-class citizen. (“Let them cry.”) Her marriage is arranged and, in the middle class, she is carefully schooled to fit in with the husband and, those very important people—who must also approve of her—his friends. To make up for lack of romance in her life, she focuses her attention on clothes, furniture, and other goods and spends much time playing cards with her women friends. The feeling against men is bitter.

As I see it, the last thing a Greek man would want is a Greek woman who is free, uninhibited, self-fulfilling, and who could really talk. He wouldn’t know what to do with her. And she would not know how to be with a man who considered her an equal. We are seeing something of this with Costis and Gella, whose marriage is a little shaky just now. She wants to be like all the other middle-class Greek girls, with clothes and free time and card games and a man who keeps her in her right place. Costis’s four-year self-exile in England has made him unfit to be a Greek husband. He told us how his family adored Gella when he was in the army and she was his mistress. But what outrage when he wanted to marry her—because she was not a virgin. Now they live in a room at his parents’ house and are looking for a place of their own.

December 17

Late afternoon. At Kolonaki Square with Joshua asleep in the baby carriage lent us by Liesel. It is old and beat-up, and I notice many people stare at it.

The square is quite small. There are ten red benches on a flagstone patio, around which grow grass, shrubs, and the small orange trees. Stuck among the bushes is the most glib bust I have ever seen. It must be some nineteenth-century king, but it looks like a plaster-of-Paris replica of Cesar Romero as a young bottom-pincher.78

The square is surrounded on all sides by the inevitable five-story white apartment buildings. On one corner is the British Embassy, on others, expensive pastry shops and cafés with outdoor tables, where, if a woman sits alone, she is taken for, and often is, a hustler.

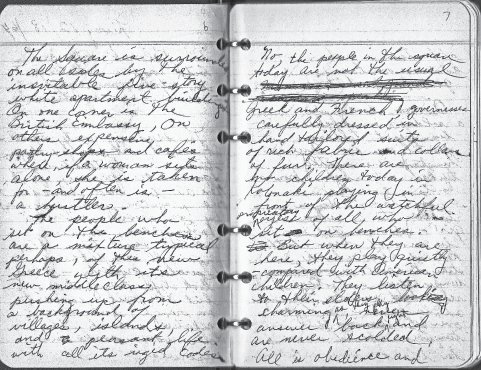

The people who sit on the benches are a mixture, typical perhaps, of this new Athens with its young middle class pushing up from a background of villages, islands, and peasant life with all its rigid codes. No, the people in the square today are not the usual Greek and French governesses carefully dressed in hand-tailored suits of rich fabric and fur collars. There are no children today in Kolonaki playing in front of the watchful, proprietary eyes of all who sit on the benches. But when they are here, they play quietly—compared with American children. They listen to their elders, look charming as they play, never answer back or fight, and are never scolded. All is obedience and affection, and a more or less quiet good time.

On one bench is a soldier in khaki, his beret tilting jauntily over one eye, his trousers neatly tucked into high brown boots, his face a rosy tan. He is talking to a shop girl—I can tell because of her clothes: red-and-black-checked straight skirt on dumpy hips and legs, a red cardigan and a lavender cardigan over that. A turquoise band around her black hair. Battered shoes covered with the Athens dust. Her face is brown, round, and doubtless—I cannot see from this distance—covered with some black hairs on her upper lip and down the sides of her cheeks. He gestures with his hand. I guess from the motions of his fingers that they are missing the amber “worry beads” Greek men so often carry. She bends forward, moving her hand from nose, to mouth, to chest, folding her arms and looking as though she is relaxed and being simply who she is. One does not see such ease and forgetfulness often in Kolonaki.

A child, a little girl, has come to fill out the square’s afternoon by batting a yellow balloon and jumping up and down.

Across the square is one of the old peasant women who often come here to sit. Her face is leathery, with lines and seams. It is the only part of her body visible as she huddles on the bench. Her hands are tucked to her lean body and the rest is draped in black. Black kerchief, black dress and sweater, stockings, and shoes. She probably wears her hair braided in long thin tails to her waist. There are many such women who come to Kolonaki and sit and gossip and laugh together. They too are relaxed, and I think they must come here to embarrass the rightful Kolonakians.

As people walk through, they are carefully studied from each bench. No one is allowed to pass unremarked. And the passersby study the benches. As in Italy, the favorite Greek pastime is the Staring Game. Across the street, on the opposite side of the square, a florist shop sells Christmas trees on the sidewalk. They stand under the orange trees in the warm, spring-like sun, and Christmas, a week away, is not to be believed.

All around the square, the taxicabs are lined up; they are big American cars, and the drivers stand and dust them with the pink feather dusters. Suddenly, there is the sound of traffic in the narrow-angled streets. More and more people pass through the square, going back to work, going to shop. I hear the singing cries of the lottery men who walk up and down carrying long poles covered with paper chances. Benches fill, and Athens has come to life after the long midday lull. It must be five o’clock.

Diary description of an afternoon scene at Kolonaki Square, in Athens, left largely unchanged in the book.

I will take Joshua back soon, before it becomes impossible to cross the streets. Athenian drivers are as bad as any in Europe, and although grown men here, soldiers even, will peek into a passing baby carriage, no one would dream of slowing down a car to let one pass safely across the street. We were almost hit four times last evening trying to cross narrow Karneadou Street, Arno furiously yelling, “What’s wrong with the bastards!”

Later

Last week, Joshua’s seventh, he began to smile, and that wild, lopsided grin breaking out when I least expect it sends me into shrieks and squeals of pleasure. Arno tells me that the past few days I’ve turned into a crooning mother. When I do “make those sounds” he looks at me with some surprise, as he’s never heard them from me before. Nor have I. It seems as though Joshua gained full consciousness last week. Went from baby animal to baby human. He stares everywhere, at everything, cross-eyed with wonder, goggle-eyed with joy. His love, however, is the couch. It is the only place to sit in our small living room and it has a high back, and when I hold him over my shoulder he can stare at it. It is a hideous object covered with red stripes and dirty little flowers, and to him it is the most exciting thing in the world. He loves it. Staring and smiling and wishing (I can feel his body’s impulse) to hurl himself at it, he moves his tongue as though he wants to nurse from it. Love, love, love. I have actually felt pangs of jealousy. “Loud, red-striped sofa,” I mutter, and it has the satisfying ring of calling another woman a brazen hussy.

December 18

On Saturday afternoon, I wheeled Joshua through back streets of the Kolonaki section. At the ends of the streets in the near distance are the high, bare, purplish mountains. You can see white Athens spilling down the slopes, climbing up the sides. There are still some streets that show what prewar Athens must have looked like. Orange and yellowish houses with shutters and ironwork balconies; in the back are hanging laundry and unbaked crockery, in the front, olive trees, lemon trees, and bird cages in the windows of what seem like wealthy homes.

Last night, I was singing Misirlou,79 the Greek snake-dance we used to come running across the campus to join. It is minor, haunting, irresistible. I sang it to the baby, who was lying on my lap. He had been smiling at me before, repeatedly breaking into those big, happy grins. When I started Misirlou, however, he became hushed, his eyes widened, and he seemed to be trying to lift himself. He did not smile once, but continued to stare at me. As I finished the song, he broke in on the final note. It was eerie—his desire to sing. Today, he is trying to make his voice speak. I talk to him and he tries to make, not random sounds, but the sounds that will be speech someday, pursing his lips in imitation of me and getting some g and h sounds. Arno was dubious when I told him last night but today he, too, saw Joshua grinning and cooing back each time I spoke. I wish I knew more about what to expect. His desire to communicate is intense and obvious at nine weeks. I don’t know if this is common or not. Anyway, he’s developing quickly and is so happy.

We had the babysitter again, and we went for another of our long walks down to Omonia Square and back. Again, I’m aware of my effort not to talk constantly about Joshua. We grabbed dinner off the stands—strudel-like spinach and cheese pastry, and the souvlaki we have been half-living on since we’ve been here. It’s nearly Christmas and a few streets are decorated in rather Turkish-looking patterns of lights. A number of shop windows are decorated and some people—not many—have lighted trees in their apartments, but for some reason it is all unconvincing. Like Japanese Santa Clauses.

Saturday, when I took Joshua home in his carriage, an old woman stopped me. Her face full of concern, she pulled up the hood of the carriage. “Pourquoi?” I asked. She showed me by rubbing the back of her hand with her fingers that it was to keep the air off him. Then she tucked the blanket up over one ear and tied his wool cap tighter. She was so concerned for him that I let her go ahead but couldn’t help smiling and when I looked down I saw Josh grinning. I thanked her and took him home in the 65-degree winter afternoon.

The Greeks are frightened of fresh air. Babies are kept in hot, closed rooms. Even our enlightened university-student sitter, Francisca, worries because the window is open in the room where he sleeps, and when I pulled him up gently she acted as though his head would fall off.

Women here are not supposed to think much.

December 20

Liesel and George’s house is slowly being built. It has already taken three years, and it will be at least one more until it is completed. They live in a few finished rooms. It is, of course, being built not only for George and Liesel and the two girls, but for George’s parents and Liesel’s grandfather, a man of ninety.

It will be a very nice house, and not unlike an American two-story home in the suburbs. Liesel does, in fact, live in the suburbs, up on a hill. We visit late in the winter afternoon. As we sit drinking the cloudy, whitish ouzo80 and water, with its strong taste of anise we have become fond of, Josh sleeps on the couch hemmed in by pillows, and we talk with Liesel. The two little girls, Antoinette and Maria, both gay and noisy in school clothes and braids, are being given their dinner of soup and the unsalted Greek bread in the adjoining alcove by a fat and rather jolly-looking cook. Actually, she not only cooks but also cleans and takes care of the girls. She sleeps in a room at the back of the house. Although she looks fifty at least, Liesel tells us that she is thirty-five; a puritanical woman who would never marry, because she thinks the love of man and woman sinful.

We gathered she was a fairly common type, and I recalled Miss Elleadou’s fleeting reference to couples who had given up on sex altogether. The maid was putting great pressure on them, Liesel said, to send the girls to church even more often than they already went. Although the maid obviously did have a great deal to say about the household, I noticed the same tone of voice I’d heard the girls in the clinic use to the nurses, whenever Liesel spoke to her.

The room we sat in had that look of an American summer cottage I had seen in other homes, even Frieda’s wealthier and more settled household. All the furniture was covered with the floral chintz: easy chairs, tabletops, straight-back chairs, couch.

Liesel got up to see to some detail of the girls’ dinner, then she relaxed once more with her ouzo. “I am so tired,” she said. “There is so much work to be done at the office these days, and between working and the house going up and the girls—whew!” She rolled her great green eyes and threw back her head on the long neck.

“The girls in the clinic thought you were American,” I told her.

“I was in America twice,” she said. “The first time I was only seventeen. I was sent to a girl’s school in Connecticut. Everyone asked my father, how can you send her? It is so full of danger and sin. She will be unprotected. I have to laugh. Although I would stay out all night with my American boyfriend, we never did anything. We would talk by the hour. Here, where boys and girls do not date at all, but meet each other only at parties, there is a lot more of what they call sin. Here, if a boy and girl want to see each other alone they have to lie and plan and arrange to meet up in the mountains outside of town. Believe me,” she said in her dry, husky way, “when you go through all that to meet, you don’t spend the time talking. I have tried to tell that to people here, but they don’t believe it. I’ve stopped trying.”

“Instant Photos,” taken for passports, December 1964, at an Athens photo booth. “Am sending you picture of mother and elf. The resemblance to Arno can hardly fail to hit you in the face, except of course, Arno would never wear a hat like that.”

(Letter, January 12, 1965.) Right: Joshua at 12 weeks (passport photo).

“How long were you in America the first time?” I ask.

“A year. Then I came back to Greece, and after a while George and I were introduced and we were married. He wanted to study horticulture, so we packed up and went to Purdue.” She laughed. “It was hectic, those days. George didn’t know English at all well, and I had to help him with it and his studies. Then I got pregnant and I was so young and we didn’t have any money. People were wonderful to us. They gave us furniture for the baby and clothes, and got me to the doctor and all the rest. Then we had Antoinette—she’s a United States citizen, you know. And we were all in one room, George studying, and the baby crying, and me weeping and screaming, because I was having so much trouble nursing her till George made me stop—” Liesel looked through this room and into that other room in Purdue eight years ago. It was clear that to her it was still utterly precious.

“The Americans were so good to me. I told you at the clinic I had hoped to be able to repay it a little. But that, too, is hard to explain to the people here. They don’t want to believe it.”

“But why not?” Arno asked. “Why do the Greeks say as their great compliment, ‘Really, you don’t seem American.’” He leaned back and put a foot up on a stool. Liesel looked at the foot significantly, and with a smile said, “Well, when a Greek or any European looks at Americans, they see—” and she stopped.

“Children?” he asked with a grin.

“Well, yes,” she admitted, pointing to his foot. She looked away for a second, then broke into a grin herself. She said a few harsh yet apparently joking words to the girls who were dawdling over their soup and trying to get our attention. Even as she scolded, Liesel still retained some look of the American schoolgirl she had once been.

“The Greeks here, if you want to know, are anti-American in good part because of the American-Greeks who come over in such number every year. They are really hated, unfortunately. And not for anything they do. But they grow up hearing about Greece from their parents or grandparents who left maybe twenty-five or fifty years ago. Then, when they see Athens, or our other towns, they are shocked. “Oh! You have electricity!” they say. “You have cars!” It is as though they expected Greece to have stood still. Then, even though it is more modern than they thought, when they get over that surprise, they complain about plumbing or other things, inconvenience, et cetera. Anyway, that is what the Greeks say. And of course, the Greeks are jealous. The American-Greeks have so much more money to spend.”

“What do the Greeks say about Americans in general?” I asked. “Not the Greek-Americans, but the tourists, the ones they see at the American Express on Constitution Square.”

She looked reluctant again for a moment but went ahead gamely.

“We say they are rude and noisy and brash. People complain that they don’t bother to get to know the country, but just rush around with their guide books and go to the Acropolis and ruins. Modern Greece does not interest them.”

We laughed. “Noisy!” I said. “The Greeks are like the Italians! You should hear the voices on our street in the middle of the night.”

“You are really bothered by all this,” said Liesel. “I wish George were here too, but now let me see about our dinner for a moment.”

“May I come?” I asked. As I stood, I could tell the ouzo had hit me hard. Feeling quite high I followed her to the kitchen, where she gave the maid the usual sharp-sounding instructions.

It was late when George came in. He was a small, thin man fifteen years or so older than Liesel. His face was complex, humorous, and homely in a Lincolnesque way. He looked very unlike the other and more handsome Greek men I’d seen. But he also seemed much more likable, more cheerful, and less remote than most of them. We drank more ouzo and his daughters climbed over his knees. At eight-thirty, they were sent off to their room. Josh woke, nursed, and slept again. At last, we went to the table. Liesel turned on the radio for some music (there is no television yet in Greece), and we sat down to an enormous, fine dinner: after the appetizer came thick, rich, egg-lemon soup, followed by roast lamb, stuffed okra, spinach and cheese pie, salad. Finally, coffee and the elaborate Greek pastries. Once, when a political announcement came over the radio, Liesel and George looked strained and conversation stopped. When they spoke next, it was in Greek. “It was the Right,” Liesel said and nothing more. They missed American food they said, and we promised an American dinner. Several hours of laughter and good talk, and Metaxa brandy. As we were leaving, I told Liesel how good it had been for me to get out of our apartment and how fine the feeling, rare to us both now, of being among friends for an evening, after being so long away from home.

“It is good for us, too,” said Liesel. “We have had no one for dinner for more than a year. We could not dream of asking a middle-class Greek couple to our house for an evening like this. Why? Because the house is not finished, the furniture not right. We have no place in our social lives for the informal visit. This was a very American evening you had! For a Greek evening we will have to go out to the Plaka for music and food one evening soon.” Once again, the feeling of a rigid structure, unbreakable rules, right ways and wrong ways. The wind was too cold. It tore at the baby’s blanket and we hurried to the little Citroën and waved good-bye from the car.

December 22

For the fourth time now in a week, I have seen a young woman sitting alone holding a baby, as I used to before Liesel gave me her old carriage. She is, I think, either American or English. I like her looks and would like to talk to her. I find that now, like the Greeks or Europeans, I too watch the foreigners as I sit in the square each afternoon. I peg people by clothes and walk and shoes and a dozen subtleties, staring sharply as the Greeks do.

It is true, unfortunately, how readily Americans can be spotted by their graceless, swinging walk, their lack of minute-to-minute concern for appearances. The English walk is as graceless as the American, perhaps more. But it is hard to tell the national differences, on sight, between groups of migrating kids (boys with shoulder-length hair wearing Army clothes and girls with straggly hair, dressed like the boys). They are from Paris, or Scandinavia, or London. We saw them all over the Left Bank81 and in other parts of Europe. The Greeks stare at them in amazement. My vision is becoming Europeanized. New awareness of “grace,” sedateness, etc. Sometimes, when I have playfully pushed the baby’s carriage ahead of me a few feet and then caught up with it, I have received shocked stares. I feel like a child. It is unimaginable adult European (certainly Greek) behavior; it is too undignified.

As she insisted, Liesel went with Arno to buy a radio. She would not hear of him going alone. He came back with a Japanese transistor for which he paid eighteen dollars—the price seems high to me. But I wonder what it would have cost had Liesel not gone.

From the American Army base station nearby, we get the news and frequent weather reports. The American passion for weather is comic here, for in Athens the weather so rarely changes it is ridiculous to report on it every half hour. But it must be habit.

December 24

Yesterday, I met Hari, the girl with the baby. She was born in Athens and went to the American school here until she was eighteen, then went to America to study biophysics. She is working for her Ph.D. at the University of Wisconsin. This is her first trip back in seven years. The baby, a beautiful, chubby, dark-haired boy, is ten months old. She says with a trace of accent that she and her husband, an Athenian she met and married at the University of Wisconsin, have just divorced, and that she has brought the baby back for her family to take care of until she finishes school in the States. Her family insists—and it hurts her—that the baby looks foreign. Hari is slight and dark-haired; she has black eyes and a long face. Her look is one of thoughtfulness; she does not look happy, yet not unhappy. She is rather plain and yet not unattractive. She enjoys her son, who burbles and grins on her lap, and she brightens when she plays and talks with him. But seated on the bench holding the child, she seems very much alone. I like her and I, too, am so alone each day as I sit my few hours in the little square with the baby sleeping or staring at the trees above, feeling each moment—even as I enjoy the sun or the souvlaki I have bought from a stand across the way, or read—that I am a stranger, that the life around me is alien, often hostile, or merely unaccepting and closed. I hunger for companionship. Today, when we left the square late in the afternoon, both going our separate ways, I felt enriched, and oddly secure in the knowledge that she will come there again and I will not sit so isolated in the long afternoons.

December 28

I try not to talk about the baby obsessively to Arno. I don’t want to become an obsessive mother. I have known—and been repelled by—several of my bright school friends who became what I call “Mamamaniacal.” I remember Arno saying to me years ago, when I first wanted a child, “I’m afraid it would fill your whole life and you wouldn’t have room for anything else.” When, if ever, do most young men actively want to become fathers?

Arno hadn’t really wanted to be a father. Yet. He objected to the accidental (read unconscious-deliberate) pregnancy. (How awesome, I suppose, to say, “I’m ready. Today, we will create life.”)

Where did I read that having a child destroys a man’s sense of his own immortality?

It is true that I no longer belong exclusively to him. The baby is a preoccupation (of necessity) that borders on obsession. We start to make love, but my ear catches a whimper and I have to try to block it out. Or he wails and we decide to ignore it, which is as bad as if I got up. Arno says nothing, or quietly, “damn,” or even grins and shrugs, but I feel guilty, responsible for having brought this upon us.

Did I indeed plan an accident? I don’t know. Never consciously. (In the old days it was enough to be responsible for one’s conscious actions—now we are held to account for what we may have done without knowing it.)

But the “blame” for conception (not that I have been overtly blamed) rests on me. It never occurs to me to say “Hey, you take care of him—it’s your kid, too.” (Partly breastfeeding is responsible. It makes an unbreakable union.)

I often think of the elflike Tony West welcoming his eleventh child in those strange Welsh hills, saying, “A child comes when he wants to be born.” Comforting as it is, I can’t really accept it; in my head I hear the voice of an old black woman I know saying drily, “Honey—it take two to tango.” But I don’t really buy that, either.

Old standard: He got her pregnant. Now it goes, “She let him.” Responsibility has gone from totally masculine to the opposite.

December 31

Tonight is New Year’s Eve and the streets are bustling with hurrying people carrying balloons and flowers and large, round flat cakes with the date written on them. The shop windows are full of small, butchered lambs, whole little dead pigs. Geese and ducks—naked of feathers—swing from their feet, their heads tastefully wrapped in paper cones.

There are flowers everywhere in newly built stands on the sidewalks, and the grocers have festooned their shopfronts with the drooping stalks of onions and the green hair of leeks. The beggars, who appeared about a week ago for the first time, have all turned out after a rest from Christmas. Beggar women carry infants as in Morocco, but without the swarms of flies around the babies’ mouths and eyes; men lead “blind” little boys from house to house to ask for drachmas (and American cigarettes when I open the door).

It is a happy day in Athens. Coins are being cooked into cakes,82 the bakery man is hoarse from yelling to the sweating bakers. Tonight, everything stays open late. Families visit and exchange gifts. We will probably take the baby and walk up Stadiou Street.83

I took Joshua to the doctor that Liesel recommended to get his first shots against diphtheria, whooping cough, and tetanus. What a surprise! He was ten weeks old that day and had almost doubled his birth weight; this usually takes about five months. Dr. Papadatous was amazed, and told me I must have plenty of good milk. He is to start with a teaspoon of cereal. If he keeps on growing like this, we’ll have to move him around by steam shovel!

That night, the shots upset him. He sobbed for several hours before I could reach the doctor by phone. When I finally did, he told me the baby could have some aspirin. By then it was 1:00 a.m. Arno came in from the Plaka and dissolved his aspirin in a spoonful of boiled water and made a little wet dressing out of shaving lotion and gauze for his arm, which was hard and swollen from the injection. After Joshua nursed, he suddenly smiled at me, his lopsided, toothless, slaphappy grin. I was so excited and relieved that he was better, I kept hugging him and kissing him. Then he went to sleep and slept soundly all night, his first crisis past.

He is a wonderfully happy boy, always staring wide-eyed at anything colorful or moving or bright. Now he is teaching himself to laugh.

If anyone had told me before that the life of an infant is so intense I don’t think I would have believed it. He can only take being awake about an hour and a half at a time. Consciousness for him is utterly exhausting, and small wonder. If he sees one new thing or has one different new experience he is quite worn out and sleeps sounder and longer. I remember how tired Arno and I were each day of our visit to Casablanca, and especially Tangiers. Everywhere we looked, life was so unfamiliar, so strange, unexpected, mysterious; our senses were like overloaded circuits under the new impressions. We slept the afternoons and nights exhausted, and were glad to leave after several days of total attention. Life for Joshua, or every waking period, must be like our days in Tangiers. I remember reading in a biography of Maria Montessori a description of an infant’s life as something like being in a factory whose purpose and machinery you know nothing about.

And how random the information must be. You look at an object and if you’re fortunate, someone explains it. Gives you a name so that you can get a grip on it. Suppose you have a feeling. For example, you are attracted, infatuated, etc. Don’t understand what’s happening to you. If you’re lucky, someone comes along and says, “Oh, that. Yes. That’s called love. L O V E. Yes. Very common.” I remember my four-month-old nephew looking at me with intense interest and something like gratitude when I named objects for him. He registered them, and seemingly with great pleasure: Cat. Piano. Music. Siren. Bells.

I want to assault my son’s senses. I often carry him from one room to another. We stand before the mirror, look at the Christmas cards and Frieda’s purple-and-scarlet doll on the dresser in the living room. Stare in the cupboards at the dishes in the kitchen. Listen to the water run in the sink. My instincts tell me what he sees and touches is forming him, and I want him to see and hear and touch as much as there is to see and hear and touch.

I have strung his crib with colored paper, silver foil, bright string (there are no mobiles or crib toys here, so I make my own). I cut shapes out of paper and then hang them on a wire across the crib. Next to the red triangle I hang the box his vitamins came in, next to that a star of foil cut from the inside of a cigarette pack. I line the crib’s sides with Christmas cards and colored pictures from magazines.

About a dozen different objects to look at swing above his head. He lies on his back and stares at them with wonder for an hour at a time. More, if I let him. (There is some unaccountable fear that he shouldn’t be concentrating so long. Am I afraid he’ll be hypnotized or guilty that I am not holding and amusing him?) I find I abhor the idea of a baby looking at a blank space. When they are newborn and face a white carriage or bassinet wall, what must they make of it? How strange and unimaginable not to know what you are and to be looking at a blank space. I read once in a medical journal that a single dot or picture placed on the wall in a hospital encouraged normal mental development simply by giving the infants and/or children something to focus on.

I notice, though, that if he is drifting off and I put a colored object in front of his eyes he will stay awake instead of sleep, and fight sleep to watch it. Which brings up a different point: how much of the sleeping that infants do is out of boredom? I have known a couple of infants who have slept almost all the time for many months, but, interestingly, they have not been natural births.

As we walk outside, I often stop under trees so he can study them from the carriage. I find I am always thinking, “How does it look to him? What must he see from that position?” From staring at the string of objects in his crib he has learned to hit at them. At first, his arm would wave and the vitamin box jumped. After a few days, he learned to aim at the box so he could hit it directly with his fist.

I must buy him some winter clothes. For soon we are going home. Our plans have been made. Arno has unexpectedly been offered a marvelous job at the magazine.

New Year’s Eve

The quietest I’ve spent since babysitting days, ten and twelve years ago. We stayed in. I got Josh to bed shortly before midnight. Determined not to let the evening go completely unmarked, I poured the last of the Yugoslav Kruskovac we’ve been carrying around for four months. There was about a tablespoon of the pear brandy for each of us. I brought the cups into the bedroom and we turned on the radio. Got Benny Goodman followed by Auld Lang Syne, and at midnight we exchanged a kiss and lay quietly for a short while, thus bringing to a close a year that gave us eight months of travel and living abroad, a novel, and a son. Thoroughly happy, I walked from room to room. What more could you ask of a year? We spent the rest of the night till dawn reading the novel, laughing aloud often—even Arno, to his own surprise. “I guess it really is funny,” he says. “When I’m working on it, I can’t tell.”

New Year’s is quiet in Athens, so different from American New Year’s, which is brimming with that utopian faith in the future. Next year will be different. I will be different. Everything will be better. I will be wiser, richer, thinner, dress differently. I will, in fact, be someone else. After almost a year in Europe, I find the idea of a people who make New Year’s resolutions touching, absurd, magnificent.

January 2

The lambs. Still can’t get used to seeing their startled, severed heads in every other window.

Day after day, I shop in the food stores, each day learning another word or two until I can buy most of our food in fractured Greek. The merchants watch me impassively, and it makes me angry and uneasy. For three months, I have shopped in the milk and fruit stores, the grocery and bakery, every day, and each time it is as though the clerks have never seen me before. Is there any greater rejection than no response?

January 3

Some men pitch right in with a new baby. Others hang back and seem afraid. What makes the difference? It seems unlikely that a grown man who can tackle ordinary household mechanics and extraordinary intellectual acrobatics is incapable of pinning two pieces of cloth together, but when I occasionally suggest he diaper the baby or learn how, in case he should ever have to, Arno seems uncomfortable and I don’t persist.

January 4

With surprise and longing, I see we do not stand together gazing wonderingly into his borrowed crib. We are so very matter-of-fact. At least at this stage, Arno doesn’t express much traditional pride in “my son,” or consciousness of what I think of as their immense, binding link. (Perhaps I have read too much D. H. Lawrence?)84 Arno has his own baby in his book and it takes, in its way, as much care and coddling as our flesh one. Arno is often amused by Josh, sometimes impatient, on the whole tolerant and affectionate, if not as excited as I would like him to be. His attitude could be summed up in a masculine—and not unhealthy—“Look, lady, he may be the new Messiah to you, but to me he’s a very nice baby with wet pants.” But I want more.

Once again, something is not quite right. But what? Seeking it out, I realize that underlying my disappointment is another of those dangerous (because hidden) fantasies. Just as I had believed there was a “right” way to give birth, I also carry in me a deeply rooted idea of a “right” way to be pregnant and then raise the new child. It is, at least partially, a legacy from the nineteen-forties Sunday afternoon Dan Dailey-Betty Grable Technicolor festivals I absorbed.85

The fantasy—a two-parter called “First Baby”—is common and probably as destructive as our other standard fantasies: Ideal Husband, Ideal Wife, Great Lover, Wedding Night, Happy Family, etc. In Part One of “First Baby,” you mistily tell your husband—by either your telltale knitting or a significant look—that you are Expecting. He does a take and looks moistly back; music plays, and in an ecstasy of masculine pride, he lifts you up, kisses you tenderly, and swings you around the room. That’s for openers. Dan Dailey would never—under any circumstances—gulp and say Oy vey, or suggest an abortion, or cover his eyes with his hands as though his life had been placed in jeopardy, and you do not see that he is in obvious peril.

Part Two of the fantasy is Baby Comes Home. In this part, the fond parents are united in and by their affection and pride. “Tea-for-two-and-two-for-tea / A-boy-for-you-and-a-girl-for-me.” Log cabin, or scrubbed cottage, or suburban house—it doesn’t matter, for all is cozy and secure. Mama is beautiful and fresh as baking bread, preferably wearing a white eyelet apron. The baby does not have colic, spit up on her collar, or crap in her lap. He does the things all good fantasy babies do: He burbles and coos and kicks and goes to sleep and gets up when he is supposed to—conveniently. And Papa. Papa is—what? Papa is, above all, Proud. Proud of his child, proud of the wife who bore the child, proud of himself. He should want to stand gazing into the crib with an arm around his wife, so that the child draws his parents ever closer together. And I have to smile at myself.

Fantasy rules us. You can see a thousand rotten marriages and know that, in all ways, yours will be different. You can remember your own childhood with its yowling kids and shrieking mamas, and still see motherhood as essentially a kind lady saying “Yes, dear,” and “No, dear,” and doling out cookies like a domestic Blue Fairy.86 You know when you are in the presence of true fantasy (really good, solid stuff) because no amount of reality can alter it one whit. It has the immovability and solidity of stone and is probably, in the end, the most durable stuff man makes.

January 5

I spend a lot of time singing to Joshua, often the French songs my mother sang to me, or the legacy of folk songs from Antioch. I have a couple of special songs I made for him—rather, the songs seemed to form themselves around him—the first week he was home. What are the songs about, the old ones?

Bye, Baby Bunting

Papa’s gone a-hunting

To get a little rabbit skin

To wrap the baby Bunting in.

Or, one of my favorites:

Hush, little baby, don’t say a word,

Daddy’s gonna buy you a mocking bird,

And if that mocking bird don’t sing,

Daddy’s gonna buy you a diamond ring

For me, because I’ve known it longest, the oldest is the lovely Fais Dodo. As a girl in Paris, my mother sang it to her baby brother; then in Cleveland, she sang it to me and my brother; and now I sing it to my son:

Fais dodo

Colas mon petit frère

Fais dodo

T’auras du lolo.

Maman est en haut

Qui fait du gâteau

Papa est en bas

Qui fait du chocolat.

Fais dodo

Colas mon petit frère

Fais dodo

T’auras du lolo.

Roughly, “Go to sleep, Colas, my little brother, go to sleep, you will have your milk. Mama is upstairs baking a cake, Papa is downstairs making cocoa, go to sleep my little brother.”

What do the lullabies tell us? What is the message behind the words? Fais dodo is a sort of nose count: everyone is home and accounted for and doing something nice for baby, fais dodo, go to sleep. We all know that at any moment, any or all could, conceivably, vanish.

Hush, Little Baby says if this doesn’t work and if that doesn’t work, we’ll try something else: Baby, you shall not want, you will not be let down—if we can help it. With roses bedight, with lilies and angels and big sisters, with mamas and with papas—Baby, go to sleep. Be at ease. For the moment—this moment—your world is foolproof, and you have—fais dodo—around you that beautiful human mess, the family.

Why is that edge of sadness in all the lullabies I’ve ever heard? Except, of course, Rock-a-Bye, Baby, which is the only one that isn’t sad, but is, with its more cheery tune, downright menacing. What does it mean? When the bough breaks the cradle will fall / and down will come baby cradle and all? Unless it is an incantation for the use of jealous siblings.

I am reminded of a passage from Rebecca West’s magnificent book Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. She speaks of medieval European man and his love of the disagreeable, which is, she says, our most hateful quality:

Natural man, uncorrected by education, does not love beauty or pleasure or peace; he does not want to eat and drink and be merry; he is on the whole averse from wine, women, and song. He prefers to fast, to groan in melancholy, and to be sterile. This is easy enough to understand. To feast one must form friendships and spend money, to be merry one must cultivate fortitude and forbearance and wit, to have a wife and children one must assume the heavy obligation of keeping them and the still heavier obligation of loving them. All these are kinds of generosity, and natural man is mean.87

Why shouldn’t our lullabies reflect, if not more joie de vivre, at least a lighter tone? The melodies are sad. Can’t a tune be happy and quiet? The lullabies I know seem to express the weary assumption of that “heavy obligation” of loving.

January 8

There goes that blasted Never on Sunday hurdy-gurdy again, for the third time today. Really, do these people believe the same myth about themselves they are broadcasting? From everything we hear, it’s more like “Never on Any Day” for any one, and certainly “Never with Pleasure.” It would spoil the joy of guilt. This hurdy-gurdy continues to punctuate each day with its mindless good humor, like a hollow laugh.

January 9

In bottle-fed America, adults in phenomenal numbers chew gum, their mouths moving like suckling babies. In Greece, where infants are denied the use of their hands, solemn men play finger games with strings of beads.

January 10

First cereal for Joshua. Three teaspoons of Gerber’s Rice Cereal with milk. On the first, he started to cry, then changed his mind and grinned wildly through the next two. He’s on his way.

January 11

Joshua twelve weeks old tomorrow. During the past week, he has gotten some control of his right hand and turns his head in all directions. He looks like a poorly constructed windup toy hitting himself in the head each time he tries to put his hand in his mouth. He is sturdy, sits up in the tub with feet propped against the side.

We got his Greek birth certificate after Arno’s five trips to various offices. It is a two-page, typed saga reminiscent of Hiawatha, Beowulf, and the Bible. It is an official government translation from the Greek to English. All about the “male of Arno,” it relates how Arno, of occupation a writer, an Israelite, came before the Magistrate, and told him how I, Frances, of occupation a housewife, an Israelite, did, on Bouboulinas Street, bring forth a male infant, an Israelite, and how he has been named “Tzotoya.” That is, no less, the official translation, with not a single name correct, except Arno.

January 10

The trip yesterday to pick up Joshua’s birth certificate was fascinating to me and exasperating beyond belief. Arno had been banging his head against bureaucracy here since our arrival. He has had to register for several different things and is getting used to the system. It was my first exposure.

The office was crowded with supplicants. A big, bare room with three desks in a row across it. At the desks were men whose little finger sported the Sign—the long, pointed, filed fingernail which show the world that these hands do no menial work, and which we had also seen on taxi drivers in Rome. The men at the desks sat and talked to one another, too obviously ignoring the people, some in peasant dress, some middle class, who came before them and waited patiently with papers in their hands.

One of the officials would pick his teeth, look at the person before him coolly, shuffle a few papers, get up and walk away, leaving the man speaking to himself. After ten minutes he would return to the supplicant, who waited patiently. He would sit down, quiz the man before him briefly, sift paper clips, talk, and joke with one of the other officials. On and on, for perhaps more than half an hour.

Arno said to me, “I saw Costis come here once. You should have seen him. It was a total transformation. He wrung his hands and pleaded and showed tears in his eyes, which apparently is expected.” And that is what we saw.

Finally, we were the only ones left. I had been holding Joshua in my arms for several hours. Now, the three men sat and watched us. There was no place to sit and in my anger I was certain that we had been left for last and now were kept waiting an extra half hour while they gossiped because I was standing with the heavy, sleeping child.

“A couple of Americans I’ve spoken with who have lived here awhile said to get very tough,” Arno whispered. “They’re not used to it from the Greeks and it’s worth a try.”

Willing to try anything, we began to storm and shout and threaten; attention was immediate and gratifying.

January 12

I am reading Confessions of Zeno, a novel of turn-of–the-century Trieste by Italo Svevo.88 Near the end is this fascinating paragraph:

I will describe some visions that came to me another day, and which the doctor regarded as so important that he declared I was cured.

In the state between sleep and waking into which I had sunk I had a dream that was fixed and unmoving as a nightmare. I dreamt of myself as a tiny child, only to see what a baby’s dreams are like. As it lay there, its whole small being was filled with joy. Yet it was lying there quite alone. But it could see and feel with a clearness with which in dreams one sometimes perceives quite distant objects. The baby, who was lying in a room in my house, saw, God knows how, that on the roof there was a cage … and that he need not move to get there, for the cage would come to him. In it was only one piece of furniture, an armchair on which was seated a beautiful woman, perfect in shape and dressed in black. She had fair hair, great blue eyes, and exquisitely white hands; she wore patent-leather shoes on her feet, which shed a faint reflection from under her skirt. She seemed to me to be one indivisible whole in her black dress and patent-leather shoes. It was all part of her. And the child dreamed of possessing that woman, but in the strangest manner; he was convinced that he would be able to eat little bits off her at the top and bottom!

Elsewhere in the same section Svevo writes:

My second vision carried me back also to a comparatively recent date … I saw a room in our house, but I don’t know which, for it was larger than any that is there in reality … The room was quite white, indeed I had never seen such a white room, nor one so entirely flooded with sunlight. Could it be that the sun was really shining through the walls? It must have been high in the sky, but I was still in bed with a cup in my hand from which I had drunk up all the caffelatte …

The sun! The sun! dazzling sunlight! From the picture of what I thought to be my youth, so much sun streamed out that it was hard for me not to believe in it … I am under the table playing with some marbles. I move nearer and nearer to Mamma …

Joshua’s eyes cannot stand the light of day. When I carry him outside, he still winces at the shock of the light; it pains him, even when it is day without sunlight.

Indoors, he is fascinated by the large, crystal chandelier. It always surprises me that daylight should be so hard to take.

The idea of the baby, alone, filled with joy, excites me. I am also reading with intense curiosity a biography of Tolstoy’s wife, drawn mainly from her diaries. How familiar much of it is to me. Why do women marry artists? It is like marrying a man with a built-in mistress, a rival one can never compete with—and who, rather than kill off, one would do anything to nurture and protect. Paradoxical and often bitter.

The gift is like an electric current which lights the man, and if it failed, he would become zombie-like—or be, simply, someone else. Can the current be separated from the conductor? Otto Rank says the artist nominates himself, usually in childhood or adolescence.89 I believe the woman who chooses him seconds the nomination—and settles for something. But what? She will never be First Lady. Perhaps she is Vice President. Or maybe she settles to reflect the light or to be around to watch the sparks fly. The current excites her. She feels she participates in immortality. My grandfather, a fanatic cantor, had himself buried, not near his wife of forty years, but near his rabbi. Was he pledging allegiance? Or did he imagine, slyly behind his beard, that he could slip into heaven on the rabbi’s coattails? For some women—myself too, I think—marriage with an artist is something like that.

Later

More thoughts on artists. If a woman is a steady acting “inspiration” to her chosen artist, then she has nominated herself (or accepted the nomination) to Musehood, achieving a kind of secondhand immortality (providing she has chosen carefully and her artist’s art will wear well). I believe I see the urge to Musehood as a kind of perverted power drive—the devious, back-of-history stuff that strong women—but not strong enough to do it themselves—have resorted to (or had thrust on them) as wives, as lovers, and as mothers.

From my own experience and that of women friends who’ve married poets and writers, I would advise a woman who wants to hear poetry about herself—or who craves a “poetic” relationship with a man—to, by all means, shun poets! To them, poetry is business (craft) and they have been the least poetic, most matter-of-fact men I have known. If one wants an “artistic” life, look to the artiste manqué.

January 13

Hari meets me at Kolonaki Square each afternoon. She is finding her return puzzling, difficult, exasperating. Asked me for my pediatrician’s name, as the one her family has been using is trying to tell her the baby has a heart condition. Her son underwent an operation for a hernia in the States in the early months of infancy and had been especially thoroughly checked before she brought him to Greece last month. Hari is not worried but her parents are ready to send him for the “necessary weekly treatments.” She tells me that even though her parents know it is not uncommon for a Greek doctor to say a child is ill in order to make money, they are afraid not to heed the doctor, just in case he is right. (One thing about the Greeks—they are not prejudiced—they extend their hostility to foreigners and fellow Greeks alike. A refreshing broadness of outlook.) Hari will see my doctor, Papadatous, this week.

Hari tells me that the newspapers her family takes give much attention to American news; daily articles appear telling about how children are mistreated by their parents (either made up or clipped from the sensational American press). She described several of these and one editorial about how American fathers have little to do with their children because of the short lunch hour and no siesta.

All these articles tend to intensify the feeling many Europeans already have, that Americans are rather subhuman, and it is always easier to exploit and cheat someone who is inferior anyway. Whether there are political motives or not, I can’t figure out. I have the impression that the newspapers the family is reading are right-wing, but I’m not sure.

Hari is shocked at her position as a woman; described how she was bodily put out of a jewelry store last week when she complained that the watch they had fixed didn’t work properly. “Impossible!” she was told.

I am getting more and more irritated at how often a man will step in front of me at a counter in a store. Apparently, it is his right to do so. Or perhaps, as in Yugoslavia, the idea of forming a line has never evolved here.90

There is no possibility of a job for Hari in Greece. And apparently getting a job is a tricky business. There are no agencies and no such thing as job hunting. We are told that if you walked into a place and asked if there were a job opening you would be laughed out. One gets positions through connections, and for women getting a job is very tricky, indeed.

Arno and I go for long walks whenever we can. Sometimes we take our scuffed carriage, which still collects stares as (Hari says) it is not good, new, or attractive enough. Last Sunday night after a long, brisk walk in the cold, we passed across deserted Constitution Square with its bright lights flashing on and off. Caught sight of our old friend Vasilios with an American couple in tow, slipping down an alley.

January 15

Nursing Joshua gives me more pleasure each day. He fingers my clothes, grins up at me now with milk trickling down his cheek. I find pleasure, although sometimes there is also discomfort, in the sensations of feeding. The special tingling and fullness as the milk comes flooding in or is “let down,” hardening and tensing the entire breast. Tension builds, and is released at the moment when the baby takes hold. It is not sexual pleasure, but the rhythm of buildup and release is not dissimilar. We are like interlocking gears. Often my milk floods in only a minute or so before he wakes and cries for it.

Sometimes the breast gets so full the milk leaks, squirting with great force in a steady stream. Occasionally, when I’ve wanted his attention, I have hit Arno with it at a distance of five feet.

Funny moment yesterday when I noticed a crumb on Josh’s cheek and had a sudden, strong desire to flick out my tongue to clean him. Catch myself at seconds with a semi-urge to lick him.

Why isn’t more said about the sensuousness between mother and baby? Men paint it and seem to assume it—women don’t even mention it among themselves. Either it is completely taken for granted or it isn’t considered at all. It is more than a fringe benefit. His waking hours infuse my life with a steady sensuous pleasure. The growing mutual familiarity, the sensations I get each time I pick him up, the good feeling I get of his heft, his smell (which is sweet even when he’s soiled, because of the breast milk) and the feel of him—we merge into one another giving and taking heat, comfort, love.

Man stays closer to his mother. A woman has her mother intimately only once; man can recapture, draw strength from, and relive physical sensations women never have again, and in turn, must give.

January 16

The night has become an entity; since Joshua’s birth it seems to belong to me in a special way. Enfolded in the hours of the night, the deep intimacy with the child.

My sleep patterns have changed drastically; I used to sleep deeply, hearing nothing. Now I sleep at a different level of attention, still aware of his slight sounds. So much so, that I couldn’t bear to have him in our bedroom.

Enormous sense of confidence from nursing the baby. No worry about changing the formula, or if he had enough. It is the absolutely perfect pacifier if you don’t mind spending a lot of time half-dressed. If you nurse a healthy baby, you know you have the right answers. So most of the time I do feel pretty sure of things, but often enough I’ll ask Arno, Why is he still crying? What’s the matter? We consult. Usually the answers are digestive in nature.

Arno’s matter-of-factness and calmness add to my growing confidence. If he were a worrier, it would be dreadful. He, too, seems to have great faith in the baby’s sturdiness and sound health.

January 17

We are having a running fight with Quasimodo and her husband about our water bill. The first month we were here they charged us about one dollar. This month, however, we were given a bill for ten dollars. Perhaps they thought that the rich Americans wouldn’t notice the difference.

We question our friends, who tell us with anger, and the by now familiar embarrassment, that such a bill is impossible. Conversation with Quasimodo would be comical if it weren’t so exasperating. The only words of French she speaks are oui, non, Madame, et, and Monsieur. Using these five words she tries to communicate the intricacies of the Athenian water system and upbraid us for our overdue remittance.

Extraction of a baby and extraction of money are basic human endeavors, however, and just as I mysteriously understood what to do during birth, I manage to understand Quasimodo, who points to the faucets and shouts, “Oui, Madame et Madame, et oui, oui!” And I shout back, “Okhi, okhi!” No! No!

Joshua cries in my arms because we are shouting and he feels how tense I have become.

Fascinating experience going to a movie theater to see love story (American). Watch Greek couples who fill the audience. Men about ten years older than their wives, arranged matches only. Wonder what they think as they watch the film with its simple American assumption of the right boy for the right girl in a blaze of passion-love forever.

January 21

Joshua is three months old. When he is six feet tall and taking on Jericho, I shall not be the one to tell him how he wept heartbroken tears yesterday because I put a spoonful of apricot in his mouth for the first time. The process of eating is certainly not “natural” at this age. They have to learn to swallow rather than use the tongue as in sucking, which tends to send the food back out.

He “talked” to us all day today, as well as to his stripes and his toys.

“When he is six feet tall and taking on Jericho …” In the baby I love, the man who will be. We love the projected man or woman almost as much as we love the real child. How do I know he won’t be four-foot-two and a coward? And if I knew he would be, could I love him the way I do? And here we are back home—once again in fantasy land. Rereading the section of the diary on how, seeing John Kennedy—who has entered the national fantasy as the lost prince—riding in an open car the night before his election, I instead had a vision of him riding on a white horse. In a way, as a mother, especially a new mother, I have to see my son, too, on a white horse.

I wonder if women believe in their children and have confidence in them in proportion to their belief in the father? I think women are much more aware of breeding and stock than they know—or would let on—to themselves or anyone else.

January 22

Rereading this diary, found Mary’s description of Greek doctors as sadistic. The word sadistic keeps coming to mind. Costis told us that the social entertainment event of the year here is an annual concert or recital given by an old opera prima donna whose voice has long since failed, but who believes she can still sing. She herself gives the concert and Athenians come to sneer and to play tricks on her—lower cats onstage in the middle of her act, et cetera.

The men will tell a woman on the street not only that she is beautiful, but, if she doesn’t please, that she is ugly and graceless. Then, there are the doctors who keep parents coming back with false diagnoses of children’s ills. The endless cheating at kiosks, in stores, in cabs—anywhere at all that money changes hands.

I am reminded of Costis’ story about a waiter who took care of his table when he, blond and blue-eyed, was sitting with a group of Englishmen in a taverna. The waiter thought all were English and after their dinner, he gave them an enormously padded bill. Costis, who had been speaking English, suddenly collared the waiter and confronted him Greek to Greek.

“Why?” asked Costis of the man. “The bill is preposterous! For what you charged us, we could buy the entire restaurant! So why did you do it?”

The waiter shrugged. “I thought someone might pay,” he said.

I am reminded of the story because of its simplicity. I don’t think the cruelties are done in a spirit of evil implied by the word “sadistic.” I think they come out of the same spirit that leads small children to mindlessly hurt animals. Simple and rather innocent. Sexual guilt may be strong here, but there are Western refinements of moral responsibility (which sometimes lead to courtesy based on empathy) that I think do not exist in this not-so-Western place.

It is in true American fashion that I review the past year; came across, at the beginning of this diary, my naïve hope that here in Greece, we will find the secret spring in which, if we bathe long enough, we will learn how to make life yield up all its goodness (“after all, these people really know how to live”). What else was it all about—the shore and the grapes, the dancing and the octopus? In Athens, we find, instead, the sour men, the unclaimed women. (“Oh Athens is not the real Greece!” everyone protests, but I don’t believe them any more than I believe that the peasant men of Crete are jolly and tranquil. New Yorkers are Americans, Parisians are French.) In antique fashion—if I had to name it—I could almost call the past year’s journal The Death of Fantasy. And that’s okay too. I’m learning—I hope—that nobody can give that secret away, even if they want to, and no people have a corner on it.

Dear to us ever is the banquet, and the harp, and the dance, and changes of raiment, and the warm bath, and love, and sleep,91

says Homer, that most cultivated of men. “Natural Man is Mean.” The sentence jeers at me. If I believe both, and I do, then the answer is simple: to cultivate, one definition of which is to foster, or cherish.

That Greece, where baths and changing clothes and sleep are sweet, and where, several thousand years ago, Homer’s hero cried out for light—if only to die by it92—is a state of the spirit only, to which plane fare can’t take you.

January 23