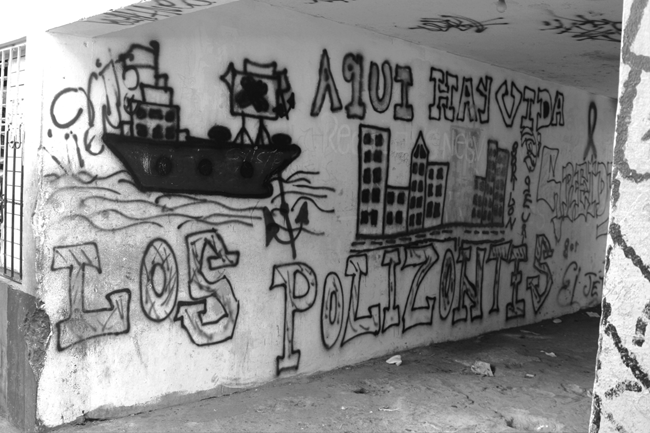

3.1 AN EXAMPLE OF GRAFFITI THAT CONTRASTS THE NEED TO ESCAPE THE COUNTRY AND THE ASSERTION THAT THERE IS STILL LIFE IN THE BARRIO—SHOT IN GUACHUPITA, NOVEMBER 2000 (PHOTO: LUIS BARRIOS).

David Brotherton (D.B.): Tell me about where you were born.

Danny: I was born here in Santo Domingo on October 22, 1962, and on August 8, 1963, my father took me to New York. They took me as a little baby. I was only 10 months old and so I grew up there all my life. I came back here in 1966 for a couple of months and in 1981 and 1991 for a few weeks. Then I came back here deported in 1999. I was born here but I really don’t remember anything from here. (July 2, 2006)

IN THIS CHAPTER we seek to answer questions that are in the forefront of the emigrant’s experience but are often sidelined due to an overemphasis on the settlement processes in the immigration literature. We agree with Sayad’s statement (2004) that it is impossible to have a sociology of immigration without a sociology of emigration. The gain of one country is a loss for another; for many in the United States, however, the introduction of new immigrant labor and their families is now construed as a “burden.” When emigrants leave their homeland, they are, by definition, displaced, both socially and culturally, even though they may eventually become “acculturated” or even “assimilated.” The process by which people leave and experience their leaving is an essential part of this all too common journey in the global marketplace, and this experience becomes a marker, if an often buried one, as subjects form and reconstitute their sense of self in the new society.

We divided our data into three themes drawn from the respondents’ narratives as they hearken back to a much earlier period in their lives: (i) reasons for leaving; (ii) feelings of loss, and (iii) modes of entry. For most of our respondents, the decision to leave for the United States was a difficult, highly traumatic, and often contradictory one. Some were too young to remember much about the decision-making process beyond the fact that they had to join their parents or their grandparents in Nueva York. For most, however, the decision was linked to the struggle for economic survival and a quest for some sense of a future that they felt they deserved. In other words, the act of leaving was a way to negate the psychosocial condition of fatalism that is common in colonized societies. In such narratives, quite naturally, poverty was the primary condition from which they wanted to escape, but often the experience of poverty was infused with the experience of repressive state policies, especially for those who left during the eras of President Balaguer and subsequent authoritarian governments of Balagueristas. As briefly mentioned in chapter 2, overlaying (or perhaps overdetermining) these experiences are the sociohistorical colonial relations between the United States and the Dominican Republic. These relations between what used to be called the center and the periphery maintain the issues of marginalization and subordination and are encapsulated in the hegemonic notion of the “American Dream.”1

In the second theme, we concentrate on the issue of “loss.” Here we are confronted with notions of cultural memory, of narratives that depict a social state left behind that will be difficult if not impossible to return to. This loss is also about the end of a period of life during which greater community trust and social solidarity provided a modicum of personal security at the local level. In a society where few are provided with any economic guarantees, the certainty of mutual family obligations and close-knit social circles built on reciprocal relations is a welcome respite. Such relations, of course, become difficult to maintain across borders and are in stark contrast to the individualized culture that is so dominant in the United States.

Finally, the third theme deals with the experiences of subjects as they made their way in airplanes, on ships, in trucks, on foot, and in “yolas” (flimsy Dominican sea craft) to the shores of the United States. How were their trips organized? What kinds of social networks were necessary? What were the dangers of such trips? Would they be prepared for yet another such voyage (see chapter 11)? These are some of the questions we ask in this section as we excavate the complex terrain of leaving for America.

D.B.: Can you tell me what you felt when you left your country?

JUAN: When I left it was with hope because people always said when you arrive over there your life will change. You are going to earn dollars. People always leave if they want to go forward, always if they want to find happiness. But, when you go for the first time you are going to another place, you are leaving your old life, someone who you were and you feel it. You are born right here, the first son, 20 years old and I left, okay, looking to improve my family. That’s it. (November 3, 2002)

In the literature describing the reasons for Dominican emigration, the primary cause is said to be economic (as expressed in Juan’s response above), followed by “political pushes” (i.e., the population’s reaction to repressive domestic regimes or to subsequent periods of liberalization) and changes in U.S. immigration laws that might allow more Dominican applicants, particularly for the purposes of family reunification (Bray 1984; Grasmuck and Pessar 1991; Guarnizo 1997). According to our respondents, the first two reasons were prominent in their narratives, and there was little mention of the third.

SEDUCED BY THE AMERICAN DREAM

Among our respondents, the theme of the American Dream was prominent, particularly for those who had emigrated to the United Status in their teens or later. Those who emigrated earlier spoke mostly of their parents or of other family members who were similarly attracted to the promise of a better life “over there.” Such messages of American prosperity and superiority are omnipresent in the swirl of First- and Third-World themes and images that constitute the urban Dominican’s daily semiotic fare. Blaring from the television screens in most colmados (neighborhood grocery stores) and in so many homes in the Dominican Republic is a constant diet of Hollywood-made productions in which the middle-class lifestyles of Los Angeles, New York City, and Miami are heavily represented. Similarly, Hollywood films are the staple diet of most Dominican cinemas, although the cost of entry is generally too expensive for working-class residents of the capital. The process of seduction continues in the U.S.-based popular music industry that is granted significant air time, although it is on television programs that American-themed music is primarily distributed. This trend is balanced somewhat by the Dominicans’ healthy respect for indigenous musical traditions, and it is notable how much air play is given to meringue and bachata rather than to rock and roll or rap music. Nonetheless, perhaps one of the most important ways in which the American Dream is communicated is through social networks of family members and friends who are more inclined to talk of their “positive” American transition than of the difficulties of settlement and any notions of “failure.”

Although the idea of American prosperity is certainly alluring, no one can predict how it might be attained. Some emigrants have achieved the American Dream legitimately as they studied, found jobs after leaving school, kept their nose clean in the neighborhood, and generally followed the examples of their hard-working parents. For others struggling in the lowest tiers of the segmented labor force, the only way to realize their goals was through the informal economy, a classic case of Mertonian innovation. The immigration literature describes various ways in which emigrants move toward the Dream after they have arrived in the United States, but less is heard from people who have seen the Dream slip farther away despite their efforts. One of our respondents, Celio, recounts being beseeched by his brother-in-law to join him in Puerto Rico after his brother-in-law had received an amnesty, a stroke of fortune that is equivalent to winning the lottery.

D.B.: Why did you emigrate? Was it for the American Dream?

CELIO: The idea came from my brother-in-law. He was in Puerto Rico and at that time had an amnesty which they gave in ’86. He was always telling us,” You’ve got to go, you’ve got to go.” Until he damaged my mind and I went. But I don’t regret it, in spite of losing everything. I’ll repeat myself, I don’t regret it because I learned a lot and I’ve got something that every man wants to have, a son. He’s not with me, but I have him. God and I are witnesses that he is there. I don’t regret it. I helped my family a lot when I was over there. It may have been drug money, but I helped them a lot. I was my family’s economic support when I was in the United States, when I was in Puerto Rico. Therefore I say these days that I don’t regret it, because I did bad things but also I did good things. (December 2, 2002)

Celio talks of his mind “being damaged” by the seduction of the Dream; it is an interesting choice of words and refers to the psychological pressure placed upon him by his family. Celio’s words could also speak to the impact of American culture on the self-esteem of a people whose efforts at independence have been struck such cruel blows by the foreign policies of Washington, D.C. Perhaps both meanings are present, for one should always bear in mind that the immigrant/emigrant is living through multiple consciousnesses, constantly piecing together the narratives of his or her journey in a never-ending quest to construct something approaching a unified self (Ewick and Silbey 1995; Riessman 1993). The tragedy for Celio lies in his permanent separation from his son (though he still clings to the possibility of some day, somewhere, getting in contact with him), which is countered by his insistence that it was all worth it. The hopes behind the original journey—the ability to make good on his family obligations, the experience of fatherhood, however fleeting, and the taste of America, particularly of New York—still mean something.

Below, Manolo reminisces about his childhood, a time when he was living the American Dream as part of a working-class immigrant family in the early 1960s.

D.B.: Did you miss the DR [Dominican Republic]?

MANOLO: I didn’t miss the DR for nothing, I was too young to know, I was basically too excited to be over there rather than over here. It was plenty over there, but ‘specially the train. The train got me very excited. My mother used to take us down to Macy’s. She used to get paid and my father used to get paid and they would say, “Let’s get the kids,” you know. ‘Specially when the winter time was coming . . . the coats, the boots, the long johns to protect us. We used to go down in the train. My mother used to hold on to me tight and my father used to hold on to the little girls, and we’d go inside those big department stores at 34th street and on 14th street . . . all that stuff specially at Christmas. My God, Lord have Mercy . . . bags for the kids, trying on the new clothes with my mother who used to take up her hair special. And then with all this stuff she’d get us ready for school, to go out in the snow. And then the weekends, the ice skating, after we’d bought the skates, ice skates, hockey skates. Man, it was very exciting, man, wow! (April 2, 2003)

Leon was also struck by the material and social benefits of his new surroundings. In talking about the American Dream, he remembered the following, again as a young boy:

D.B.: How was it when you started to hang out?

LEON: I didn’t hang out ‘cause I was only a little kid, but I saw everything. I saw big rooms, a nice bed, more food, food in the refrigerator . . . because back then we had no refrigerators in the D.R. I see the refrigerator and its cold and the cabinet full of clothes, you know, it was nice. Then when they took me to school, you know, I felt good, like a different environment, I felt safer. (March 3, 2003)

Safety and educational possibilities are both important elements of the Dream for deportees, as evidenced by Alex who wistfully remembers his experience of public schooling and its promise of social ascent for the poor.

ALEX: God bless them (the United States [added by the authors]) because you know, they offer you a lot of things, they offer you school, they give you money while you’re going to school, you know, they give you free college and things. I don’t how they call it but you have a lot of opportunities over there. But when you’re young you don’t realize those things, especially when you don’t have no family next to you that can give you the proper guidance. (March 5, 2003)

In contrast, Andres, below, asserts that the Dream was more about people keeping themselves to themselves, staying out of “your business.” It should be noted that cultural conformity is held in high regard in Dominican society, with a strong emphasis on the collective conscience, quite different from the U.S. traditions of individualism and personal autonomy.

D.B.: What did you like about the United States?

ANDRES: Well, I liked a lot of things. The United States is nice, things are easier there. With a little money you can buy a lot. The food is cheaper, the clothes are cheap, many things that in all honesty in your own country are difficult.

D.B.: Did you notice any competition with other groups, like with people who wanted to be better than you or mess with you?

ANDRES: No, no, no, because over there people live within themselves. They live for themselves. They don’t live, let’s say, uh, mistreating you, criticizing the way you dress. No, no, no, over there every one is trying to better themselves and move forward. (January 9, 2003)

Nonetheless, the American Dream does not produce the same bounty for everyone. Some of the respondents recounted how betrayed they felt by the Dream. Their expectations unfulfilled, they admitted to having been deluded, to having given up everything for this mythical life. For some, the cost of missing the Dream was severe, especially the sense of dislocation and disruption that it caused to their previous lives. One might consider this to be “sour grapes,” that the subjects may not have prospered in any case, especially given the limited opportunities that existed in the country generally. Nonetheless, Cecilio’s comments are noteworthy.

What happened is that I went crazy with the idea of seeking the American Dream. And therefore I left the country. If I had stayed and not been carried off by the American Dream I would have gone on to study. I would have gone to college and I would be a professional by now. Instead, I was in Puerto Rico from ’89 to ’96, between Puerto Rico and New York, that’s practically seven years. In those years I could have graduated here, but seeking the American Dream I lost it all, except my life which is most important! (March 3, 2003)

DEALING WITH POVERTY

The Dream, of course, is very much linked to the experiences of unrelenting poverty in the Dominican Republic, where so many are living in permanent hardship with scant social mobility (see chapter 2). For many respondents, poverty was a normal state of affairs, especially growing up in neighborhoods during the 1970s and 1980s, with little notion of relative deprivation. In the following, deportees talked about the various ways they experienced poverty during a more general discussion that focused on their reasons for leaving.

D.B.: Can you tell me about the neighborhood where you were raised? Did you see or live through poverty in your childhood?

AGUSTIN: Yes, lots of poverty, the first I remember was Jualee, then later in a place they called Lenguaazul, that nowadays is called Sánchez Jaumatinamella. Then I remember going to El Faro, that’s up that way, then Cristo Rey and lastly here in Villa Duarte where I have been all this time. (May 3, 2003)

D.B.: Could you tell me if you experienced poverty during your childhood?

ANDRES: Well, my grandmother was very humble. She was a dressmaker and used to sew in a dressmaking workshop so we could eat and take care of the house. I used to do the house chores, help out our aunt for my grandmother. You know, we lived the normal life of people . . . the simple life. (January 4, 2003)

GIPSY ESCOBAR (G.E.): Tell me a little about the neighborhood where you were raised?.

EIXIDA: It was peaceful. I had many friends, boys and girls and it was beautiful.

GE: Did you see much poverty?

EIXIDA: Yes, there was, yes.

G.E.: In what sense? Did people not have enough money to buy food?

EIXIDA: No there wasn’t, that’s to say, you could only afford to buy one piece of clothing a year and then you had to worry about eating every day. My father was always worried, always worried about providing food for the household. There was nothing, no refrigerator, no water, no light, nothing. (May 2, 2003)

In the first quote, Agustin is naming a number of poor barrios of Santo Domingo, with Jualee among the most deprived areas in the nation. These areas are assiduously avoided in conversation, with any mention of their names provoking a raised eye brow, an unsubtle reminder that these zones of deprivation (as expressed in the third interview) are seen as pathological places where indices of interpersonal violence are as high as almost anywhere in the Americas.2 Poverty, therefore, was identified as a very real structural constraint, a condition that determined the school one attended (if one attended school at all) and dictated the space available for housing and even the number of people with whom one shares a bed.

D.B.: Did you like to study in school?

SANTO: Yeah I liked studying but it wasn’t that easy because I had to work and therefore I had to quit school. (May 8, 2003)

D.B.: Did you see a lot of poverty?

SANTO: Yeah, lots of poverty, yes.

D.B.: And how is the experience of poverty?

SANTO: There is still a lot of poverty, lots of poverty still remains.

D.B.: Poverty as in people don’t have enough to eat?

SANTO: To eat you have to work. You have to go to the country and even in the country there isn’t a lot of work right now, there’s not much production.

D.B.: And at your home, was there enough room for the whole family or did you have to share a bedroom with other people?

SANTO: I shared a bedroom with the other siblings, because the house was very small.

D.B.: How many bedrooms did you have?

SANTO: 4 bedrooms.

D.B.: For 10 children and the parents.

SANTO: For everyone, yes. (laughs)

D.B.: So, did you have to spend a lot of time outside?

SANTO: Of course. (laughs) (April 3, 2003)

LUIS BARRIOS (L.B.): Tell me about your childhood.

NESTOR: About my childhood? There was little happiness because back then, I always had to sell things. My mother never bought me trousers, never bought me a pair of shoes. I had to sell things with my brother, selling bread, what they call “pan bolita” and “caramelitos” that are made from coconuts, and cleaning shoes. From that I earned my money which got me my trousers. Half my money would go to my mom so she could buy things for my sisters. (May 3, 2005)

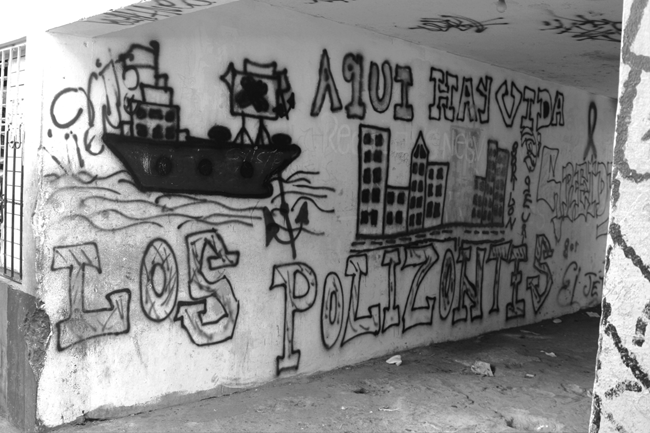

3.2 A TYPICAL DWELLING IN THE POOREST NEIGHBORHOODS OF SANTO DOMINGO. APPROXIMATELY 70 PERCENT OF SANTO DOMINGANS LIVE BELOW THE POVERTY LINE. THE CONTRAST BETWEEN THE DAPPER, SELF-CONFIDENT “LEONEL” IN THE POSTER AND THE DISHEVELED HARDSHIP THAT PERVADES THE COUNTRY IS MORE THAN JUST AN IMAGE. (PHOTO: LUIS BARRIOS).

D.B.: So you saw a lot of poverty?

JOSÉ: Lots of poverty, I lived in here in a yard, where there were like 14, 15 dwellings, like bedrooms, 8 or 10 people lived in each bedroom. Sometimes 10 in a bed! (May 28, 2003)

In the Dominican Republic, a heavily patriarchal society, there is a tradition of men fathering children without taking responsibility for them, as Luis attests below.

LUIS: Well, it wasn’t too difficult because my dad never gave me the support that I needed, do you understand me? My mom raised me, my mom was my dad and my mom. She gave me what I needed. May God have glory even on my dad, let’s say, because the feelings I once had are gone. Before I could not forgive him because he put me through a lot of hard times. If my dad had supported me, I wouldn’t have gone to prison in the United States. Why? Because I would’ve been devoted to working and I wouldn’t have had such a materialistic mindset, do you understand me? But because he didn’t give me any support I said: “OK, I’m leaving my country and I’m going to make money any way I can.” So I began to do things that weren’t right, do you understand me?

But poverty has also changed, particularly in more recent times. Part of the change reflects the great increase of commodities flooding into the Dominican Republic and the new social strata that have emerged. As the formal economy has developed with more foreign investment, the informal economy has grown with a massive increase in drug trafficking. The country is now a major transit point for Colombian drug cartels, with a growing local trade primarily in cocaine and heroin; concomitantly, its banks ensure that it is one of the world’s leaders in money-laundering (U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration 2002). According to the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Dominican Republic is also a leading producer of false personal documents such as passports, identity cards, and social security cards.

D.B.: And were drugs being dealt there?

AGUSTIN: Now there are drugs everywhere, even your own children and your little brothers can get involved. You tell them to stay out of it, to not get involved with people not knowing what they are doing. If it turns out they carry drugs and they get arrested, you also get arrested. So as someone who knows I tell them not to hang out with those types of people.

D.B.: Were there any drug sales when you were growing up?

AGUSTIN: Down on that street, not on this one, in El Proyecto, they used to sell, they used to sell drugs down there. (November 28, 2002)

DB: Tell me about your neighborhood.

JAVIER: My neighborhood is one of the most well known in Santo Domingo because famous politicians like Leonel Fernandez have come from there. It’s also where the most drugs are dealt, one of the most notorious neighborhoods for drugs, most recognized for robbery and gangs. (June 5, 2003)

Deportees also talked about their struggles to emerge from poverty with emigration as the last and not the first resort. Andres discusses this below, as he tries to explain the obstacles facing youth and adults who reside in poor and criminalized areas. The reader should be reminded that the Dominican Republic still practices “preventive detention” which means that suspects can be arrested and placed in prison while they await trial, which can take several months and even years (see chapter 10). The lack of due process in the system ensures that many youths and adults have criminal records that stay with them for life which severely affects their employability. As Andres attests, all the will in the world often does not trump the constraints of dependency, discrimination and the normative level of poverty wages paid to labor.

ANDRES: Some youths, if they have a record won’t easily be given work. Why? Because they see them as antisocial. They see them as not able to work. Why? Because they fear this person might do something crazy. They fear losing their business, so they make it difficult for you. But there are many ways you can earn a living. It could be selling chimichurri on a corner, running a corner store, selling water in the streets, there are many ways to earn a living. It’s not necessary for you to go over there (The United States [added by the authors]), but you resort to having to go over there because things are made a lot easier than here. There, at least with your small or large earnings, you manage and help your family, but working in your own country, you work a lot and earn little. (January 9, 2003)

Finally, it should be mentioned that some deportees understood poverty differently. They described it in culture conflict terms, as the result of the newcomers with different customs moving in and creating the conditions for social disorganization. Such new residents usually came from rural areas, and there was a hint of prejudice in the respondents’ answers. However, the same respondent also saw strength in these poverty-riddled communities as residents came together to share and give each other much needed support.

D.B.: Tell me about the neighborhood where you were raised. Did you live through a lot of poverty in your childhood?

ALBERTO: The neighborhood where I was raised was a very humble neighborhood. Still the neighbors were calm and human. If you needed something the neighbors gave you it, but as time passed, you know neighborhoods bring in other people, let’s say, with other customs. Then the new customs hurt those that live there. If you live here and a fucked up neighbor moves in, problems start and right then they start to produce problems. So the neighborhood was calm, but later people started changing it, people were coming from the south, from different places until they had completely occupied the neighborhood. I told them this is what can cause problems, you could even cause deaths with this, let’s try to make it for our children, because we need each other. (January 9, 2003)

FOLLOWING THE SOCIAL NETWORKS

Although many Dominicans emigrate for the structural reasons we have described, there are many who emigrate on the basis of the more personal circumstances of the transnational networks they were born into (Levitt 2001). This is particularly true of deportees who were taken by their parents, grandparents, uncles, or aunts and had little choice in this particular life trajectory. Of course, the underlying causes for the move may well be poverty or political repression; for many women, it is the insidious effects of patriarchy as expressed in domestic violence or intrafamilial abuse. Whatever the structural roots of the move, many subjects remember their emigration—if they remember anything about it at all—on a personal level, as the result of someone else making a decision to join the family “over there,” of being displaced with few questions asked. In our sample, more than half of the subjects left the country before they were 5 years old. Below, Danny, Luis, Alex, Ferna, and Jose provide typical accounts of this process; Ferna, however, was much older (18 years old), and the gender-related reasoning behind the move is obvious.

D.B.: It must have been confusing with your mom just leaving for the United States with your sisters. . . .

LUIS: Well, she had to go.

D.B.: She had to? I’m just trying to think of what you felt back then as a little kid.

LUIS: As a little kid, well, like every kid missed their mother, you know, it was a little tense, but then, since they explained to me that things were getting better and I could see in my surroundings that there was more food, more milk, more clothing, I felt better. You know, they kept telling me that I will be going soon, so that kept my spirits up. (April 2, 2003)

ALEX: Yeah, he [the father] had three more kids, girls. And then he had his life going on and I needed to have my life going on too! And he asked me: do you wanna go to the United States over there? You wanna leave me? And I started crying, I said, “Papi, yeah, I wanna go to New York but nobody has come to bring me to go to New York.” That year I went to New York, to my mother’s house, but it was like a nightmare when I went to New York, even though I love New York, you know, I went to the wrong neighborhood. (March 5, 2003)

D.B.: Yeah. So, tell me about the move to the United States, how did that occur?

FERNA: Because my parents told me not to stay here, they wanted me to stay over there, marry an American and get a better life. (May 9, 2006)

DB: Do you remember your father saying to you, “Look, we’re leaving for New York?”

JOSE: Oh yes, I remember that clearly. He came in 1966 to get me when I was 3 years old but my mother told him “You can’t take him, he’s too small. Come later when he’s bigger.” He had the ticket and everything, the passport, I had the suitcases made and then my mother said, “No.” My father got mad and then came back four years later when I was 7 and then my mother said” Ok, you can take him, he’s bigger now.” (May 1, 2003)

In another example of the influence of these networks on decision making later in life, Leonid remembers being pressured by his grandmother to come to Miami because of its “opportunities” and his “facility” for schooling. Leonid’s grandmother had been helping keep his family above the poverty level in Santo Domingo, as was the lot of so many in his neighborhood (in this case Villa Duarte); after years of this support, Leonid made the move to Miami in his late teenage years.

D.B.: Tell me about school.

LEONID: I went to San Juan Evangelista. I went to different schools, I had the facility to learn. My grandmother lived in Miami, Florida, and wanted us to have a good education even if you had to pay for it. So, we went to some private schools here in Santo Domingo.

DB: And how did you move to the U.S.?

LEONID: Well, I moved to the United States when I was 15 back in 1988. I was still in school of course and I went as a student, with a student visa to continue my studies. That’s what I did. I went in August, August 5, 1988, and in September I was already enrolled in school in Miami, Florida. I remember that was Kinlock Park Junior High School. I started in 9th grade and I already passed because of my language.

D.B.: So, you went to Miami in the 9th grade. But, why did you go? Did your mother send you or what happened?

LEONID: Exactly, my grandmother sent for me because she was a U.S. citizen.

D.B.: What did she say?

LEONID: Better education, more opportunities and you’ll get a better job. (April 10, 2003)

And then there is Luis, who, as an adult, traveled to Miami for a holiday and then followed his social network up the eastern seaboard to the Dominican community in Boston, joining a neighborhood friend who was “dealing drugs.” This was an unfortunate combination because it lands the subject in a Massachusetts prison for four years after barely setting foot in the United States for three weeks (see chapter 5).

LUIS: I stayed there (New York City [added by the authors]) for about a week. By the end of the week I called my house and I talked with my mom and asked her where my brother was living so I could go there to spend my vacation. When I got there he told me that his apartment was very small and that he was waiting for a larger apartment so we could live together. So I said to him how can I wait . . . the entire time I was thinking he was going to help me out. Then my friend from Santo Domingo found out that I was in New York and called me up and said: “I’m coming to get you tomorrow.” The next day he showed up with his wife, he lived in Boston. He told me: “Let’s go to Boston because in Boston I am alone. I don’t have anyone, up there, we can work together on things.” I told him that I’ve been thinking, about selling drugs some day but not yet. He told me don’t worry “I’ll help you with whatever you need.” We went by car and when we arrived in Boston on Washington Street in Lynn, he took me to an apartment in Hannover Street, then told me: “Look, we’re going to live here.” He had a Boricua friend, a Puerto Rican, who sold drugs with him. Then he told me:”Come see how things are done.” I told him that what I want to do first is find my way, even if I have to go back to my country and then return to find out. So, we left, I made an appointment with a lawyer who was charging me $2,500 to work on my residency. I made an appointment for December 5th of ’89. I was living there in his house for three days, then on the 4th day he said to me: “Let’s go check out Lynn.” We went for a walk, a Puerto Rican in a car showed up with a police officer in plain clothes and he told my friend, “Listen, this friend of mine is looking to buy drugs.” My friend told him: “I don’t sell drugs” because he didn’t know the other guy, who was a cop. So he told him: “Listen, I’ve known him for a long time. Whatever happens I’m responsible.” From then on he began the conversation with the police officer in English and I didn’t know what they were talking about. Although I could figure out more or less what they were doing because I was watching their movements. (February 27, 2003)

Finally, there is the respondent who undertook the journey to the United States to “make it on his own.” But to do so he needed the networks that were already in place: someone to talk to about the process, a contact to cross the borders, and a family member on the other side to welcome and settle him. In the following, the respondent describes his journey; although he insists it was all due to his individual determination, it is obviously a highly coordinated effort involving family, friends, and acquaintances:

S.: I went to the United States because of the situation here, life was too hard, so I scraped together some change working here and decided on the United States.

D.B.: Do you have connections over there in the United States from before?

SANTO.: No.

D.B.: But, what happened to the family, your father. . . ?

SANTO: Oh, I have one of my uncles that lives over there, he lives over there for 40 years.

D.B.: But was it because of this connection with your uncle that he said, “Look, come to the United States to. . . .”

SANTO: No, I decided to go on my own.

D.B.: And what happened? Did you go to the embassy to get a visa?

SANTO: No, it was at the Mexican embassy that I got a visa, I went to Mexico. I stayed one month in Mexico and from Mexico I crossed over to Texas and from there I moved across to New York.

D.B.: So were you legal or illegal?

SANTO: In the United States I was illegal, but in Mexico I was legal because I went with a visa from here.

D.B.: So you arrived in New York in ’78 and what happened?

SANTO: I called my uncle and he came to pick me up where the person that brought me had left me—because it’s a person that brings people back and forth, from Mexico to there. So I called my uncle and he came to get me. So then I went to live in his house and from there he presented me to various people and I was meeting friends, from there I met my wife and then we married like in 6 months. She got pregnant and after two years we had a child. And then from there to here she sent me to ask for my residency, after like four years they gave me residency. (May 2, 2003)

Many respondents in our sample had experienced various acts of state brutality and repression in their everyday lives. These objective and subjective experiences of moving from the indirect violence of poverty to the direct violence of state vindictiveness strongly influenced respondents’ decisions to emigrate and comprise an important part of the process of exiting (Salmi 1993).

D.B.: Tell me about your role during the Revolutionary period.

ROGER: I was a young boy, 14 years old, and joined a squad of school students to resist the marine invasion of Santo Domingo in 1965. I was a sniper and I used to shoot the marines when I could and then disappear. I saw people die right in front of me, right there, with blood all around me. It was a very scary time for me but I was defending my country. We were being invaded, you have to understand that. After the resistance died down they were searching for all boys in the capital of my age. My father said that I had to get out of the country as soon as possible otherwise I would probably be killed. It was a crazy time back then and a lot of people were disappearing. They would see some young boys on the street in the evening and they would just come and disappear them. It was that kind of time. So I got out and I left for New York to join other members of my family. That’s why I left here. (October 1, 2002)

D.B.: Was there a lot of political violence during this time?

JAIME.: During the time I grew up yes because Balaguer was around for 12 years, lots of murder, the Banda Colorada (a group of assassins formed by Balaguer to murder opponents [added by the authors]) were killing and if you weren’t with them you were a communist. You know the system that we have, if you were not with the regime you were an opponent and you were in a mess. Here this is always a presidentialist and militaristic country. Here the military are the ones that rule. (December 3, 2002)

JUAN: During the time of Balaguer? For 12 years that was a bad time.

D.B.: What was bad about it?

JUAN: When you were young you couldn’t feel safe, because anybody could do anything to you. They would say you were a communist and you just meant nothing, nobody cared. If somebody in the government was saying that you were a “hot head” you could die that day and nobody could say nothing.

D.B.: So, did you lose any friends?

JUAN: Not really friends, but people that I knew.

D.B.: They were killed?

JUAN: Yeah, they got killed. (April 12, 2003)

D.B.: Do you remember any of the political violence back then?

LEON: Actually, they were talking about Trujillo and I felt a little bit scared because I used to see the people running away. They used to say, “Trujillo is coming, Trujillo is coming” and everybody used to jet into their houses and close the doors, you know. So I never really actively saw Trujillo, I used to hear about it because people would run from him and they were scared of the police, scared of the cops. Every time I used to see a cop I’d think: “Oh, wait a minute, he’s gonna kill me, he’s gonna kill somebody.” Because that’s what everybody thought, that’s basically the only memories I have. (March 15, 2003)

D.B.: Did you see a lot of violence growing up?

JOSE: Yes, my uncle was head of the PDM, the PDM was the Popular Democratic Movement, communists.

D.B.: It was your uncle?

JOSE: Yes, and my uncle was tough, tough, tough. My uncle, the whole family, we are combatant aggressors, you know what a combatant is? (Cell phone rings, interview is interrupted.)

D.B.: So the violence, tell me what happened?

JOSE: Pow, pow, pow, pow, it was a deal like this, and like I said the police fired at him and he fought the police.

D.B.: Really?

JOSE: Yeah, and he jumped over the wall.

D.B.: Your uncle used to live with you guys?

JOSE: Yeah, but my uncle now is in the States. He got out of here, yeah. (December 8, 2002)

These interview excerpts refer to a period roughly between 1965 and 1985, during which time it is estimated that 5,000 Dominicans disappeared at the hands of police, military, and other units working on behalf of the state. It is important to remember that, unlike other countries such as Chile, Guatemala, and South Africa, the Dominican Republic has never had its Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The victims’ families and friends still do not know what happened to their loved ones, and the nation has never fully confronted its past, which would be the hallmark of a potentially vigorous democracy.3 As we shall discuss later, there are many remnants of this authoritarian past alive and well today. In this vein, Juan’s words resonate strongly: “Here this is always a presidentialist and militaristic country. Here the military are the ones that rule.”

We have discussed some of the reasons for emigration from the Dominican Republic, providing the emigrants’ own words where possible. Leaving one’s homeland is a complicated cultural and psychosocial process that involves hope and a feeling of relief combined with a sense of loss and regret. Each emigrant’s experience depends heavily on the precise circumstances of the departure, the age of the subject, and the welcome at the end of the journey; nonetheless, removing oneself from the close-knit, fairly homogenous cultural community of the Dominican Republic is emotionally difficult. In addition, the landscape for those moving to the United States under these conditions has changed radically in the United States in recent decades. As the welfare state has been shredded and the country has moved further toward free-market ideology and government through crime and fear, everyday life has become more fraught, less secure, and more risk-based (Bauman 2004; Beck 1992; Simon 2007; Young 2007). In this period of rapid societal change and cultural instability, deportees had to make sense of their pasts, looking back to a period that for some felt more collective, more reciprocal, and less ravaged by disunity, competitiveness, and socioeconomic instability. This may seem to be contradictory, given that the period being discussed was one of extreme political repression; nonetheless, for some, this period of authoritarian paternalism was one of greater social calm:

ALEX: I used to live here in the Colonial neighborhood, decent people . . . before it was better than now, now you can’t even talk to people. Before you used to meet people in the same neighborhood, we used to cook and invite them to come here, when they had no food. Now, these days, nobody do that no more. Before they used to leave the door open, now they don’t do that. Things change. . . . (March 5, 2003)

D.B.: Tell me about where you grew up.

MIGUEL: Back in the days it was a lot different. Everybody got respect for other people, you know what I mean. It’s like in older places, you know what I mean, it’s a neighborhood, you know, black people, all together. . . . (January 25, 2003)

MANUEL: I went to school here under the dictatorship, it was very disciplined. We had to have our shoes shined, our khaki pant pressed, our shirts pressed, they used to give us breakfast in the morning, it was very disciplined. The schools here they used to run like schools, not like now. Before they was more strict, check your ears, check your nail, check everything, no fucking about. (January 26, 2003)

D.B.: How was it back then?

FREDDY: During that time it was good. Yeah, there was not so much evilness, There also was not as much corruption as there is now. That’s to say we youths were calm, we always liked playing ball, passing the time. But not now, now the boys are growing up with knives, guns in their hands, and there is too much corruption. (February 4, 2003)

Freddy’s use of the term “evilness” is instructive. It refers to changes in Dominican life that he finds incomprehensible. For him, the rise of intracommunity violence is about doing antisocial acts for the sake of it, for the high (Ferrell 2001), and for the emotional not economic satisfaction it brings. Although he was raised on the streets of New York City after emigrating at nine years old and has spent more than a decade back in his homeland, he cannot abide this growing insecurity in his daily life. Many deportees lament the passing of a more communal era, and they are confused and demoralized about the present fragmentation of the local community and what this augurs. They are in an ideal position, however, to see the Third World meet the First World for they have often been socialized in both and they do not always like what they see.

For example, the deportees constantly remark on the youth around them, particularly on what they regard as a desperate search for identity in symbols of consumption and hedonism. Freddy’s comment about young people’s penchant for artifacts of violence must be viewed in the context of their struggle for daily survival, the mushrooming gang culture, and the new Hobbesian approach that complements the adoption of market solutions for the nation’s underdevelopment. Many subjects often reflect upon how difficult it is to comprehend the transition from a culture of state violence under the previous authoritarian regimes to a culture of interpersonal violence. Part of the challenge lies in the disjuncture between the ideology of individualism and the long awaited meritocracy that should come with deregulated markets and westernized “efficiencies.” The stark reality is that the Dominican labor market is highly segmented, with poorly paid Haitian workers doing most of the construction, road repairs, and agricultural labor, whereas the better jobs are often regulated through patronage and clientalism. As a result, the deeply unequal socioeconomic power relations are maintained, and the three or four families that control great swaths of the economy continue to reap massive profits.

Working-class and poor youth are caught within these contradictions, and they react and adapt accordingly, searching for respect in the street world (Bourgois 2002) and trying different modes of innovation (Merton 1938) to exploit their inherited opportunity structures (Cloward and Ohlin 1960). Nonetheless, their actions lead to a form of implosion, an insidious form of social reproduction that is only partially resisted (Brotherton 2007).

These new currencies of youth violence are unprecedented, aided and abetted by police and military forces that are themselves socialized and trained in techniques of violent repression. This contradiction cannot be resolved as long as the country remains in its dependent state, riddled by what Freddy sees as “too much corruption.” Looking back to look forward is difficult for the deportee, caught between the tangled webs of transnational experience in the past and their more static and fixed locations in the present. Essentially, they are stuck in a particular form of arrested psychosocial development, and they respond by imagining, lamenting, and waxing nostalgic, reinventing both the Dominican Republic and New York City as they do so.

This section focuses on how subjects journeyed to their destination: the levels of planning involved, the roles played by family members and friends, the social networks, the formal and informal mechanisms used to cross borders legally and illegally, and the sheer determination required to carry all of this through to the end. Getting to New York, Miami, or Boston is not just a boat ride away for many deportees. Although most of our sample went to the United States as children, legally brought there by family members, a significant number arrived illegally. Many of them tried to emigrate during periods when the United States was increasing restrictions on Dominican entry (particularly after 1986), and it was no longer a time when, as one deportee put it, “All you had to do back then was go down to the embassy and ask for a visa. No questions asked. Seriously, it was like buying a bus ticket. Of course they (the United States [added by the authors]) wanted to buy the peace here after the Revolution, after the Marines came in. But that’s how it was. It’s hard to imagine that now. . . .” (November 9, 2002)

Carlos’s experience is typical of that for many of the respondents. His economic situation was making life impossible, working for nothing, barely scraping by, and so he inquired about how he can make “the journey.” Carlos traveled to the north of the island, around the town of Nagua, which is the favorite staging post for many emigrants to make it to Puerto Rico in privately owned boats. He knows someone who knows someone, and with a couple of thousand pesos, usually around $500 to $1,000, one can buy a place in a boat with a range of other hopefuls, men and women of all ages and from all over the Dominican Republic.4

L.B.: What’s the best strategy to leave from here for the United States?

CARLOS: Well, I had to go on the journey because of what was happening. Why? Because work does not provide me enough, what I was earning, then I was presented with an opportunity to take a short trip in a raft. They asked me for some money, I scraped it together, and I gave it to a gentleman who helped me go to Puerto Rico and from there I got to the U.S. little by little. I knew a friend of mine over there. . . . We were from this same place, the same area and through him I earn a living and with time I managed to go to New York. (November 29, 2002)

Most of the social science literature on crossing the border relates to the divide between the United States and Mexico (e.g., see Chavez 1997). There are few accounts of crossing the border into the United States from the Caribbean and fewer that detail this journey from the Dominican Republic. The literature that does exist is primarily journalistic and is often prompted by a tragedy, such as the publicized case in which Dominican emigrants spent days on a boat trying to get to Puerto Rico and, according to media accounts, resorted to cannibalism (Vargas 2001). Most attempts to cross the border fortunately do not turn out so tragically for Dominicans; nonetheless, these are extremely physically trying and emotionally draining experiences that require a great deal of personal and collective resourcefulness as described by Celio:

CELIO: There were 76 of us. We arrived Friday during the early morning hours which was actually Saturday. We spent Saturday waiting and making calls for them to pick us up.

D.B.: How did you get there?

CELIO: We entered through Rincones beach.

D.B.: On board what?

CELIO: A makeshift raft, made from large wood, about 30 feet.

D.B.: How much did you have to pay at that time?

CELIO: In those days I paid around 1,500 pesos. It was a sister of someone that lives here who helped me, her name is Lucía. She spoke with him and trusted him and he told me, “Get me 1,500 pesos.” He almost did it for me for free because he usually charges more money. Then, nothing, I waited a month and then they called us and took us to Miche and from there we left. This was in ’89.

D.B.: Were you scared?

CELIO: No, I wasn’t scared because I was 20 years old, when you are 20 years old you don’t have experience.

D.B.: It was kind of like an adventure?

CELIO: Exactly, and I am the adventurous type, I like adventures a lot. I won’t tell you that I wasn’t scared in the beginning because you are in the sea and you look from side to side and you don’t see anything, the only thing that you see is water and one spot what they call Desecheo, which is after the Mona Channel. The ship felt something like a blow in the bow, in front, and water was coming in. We had to remove water, then I was feeling a little scared, but then I thought, I said: “Ok, there’s 76 of us, I’m not going to die alone, 75 more will die.” And so, from that, from that, that helped me a lot. (March 3, 2003)

As Celio indicates, the boat ride can be extremely hazardous and drownings are not infrequent. There is usually little shelter from the elements; most of the boats do not have sufficient life jackets for the passengers, and they are often dangerously overloaded. We can only imagine what it must feel like to be sailing in the middle of this vast expanse of water, completely at the mercy of the crew and the weather. Who will be there on the other side? Will I get past the U.S. Coast Guard? Will my contacts still be there? How will I make it to New York City? All these questions are going through the head of the deportee, but Celio likes to remember it as an adventure; perhaps this is his defense mechanism, one that is used by many subjects who found it difficult to talk at length about this aspect of their past.

There were some deportees who never made it across the border at all, at least the first time. Caught by authorities on their arrival in Puerto Rico or at the Mexican border, they were returned to the Dominican Republic, sometimes spending time in an immigration jail or detention camp before being sent back to the Dominican Republic. Those who were denied initially often managed to gather the material and psychological resources to try once more, as Eddie reveals below:

D.B.: You tried to go how many times?

EDDIE: Several times, one time, I was going to go to but I turned back. I decided that I wasn’t going to go no more.

D.B.: Where from?

EDDIE: Miche, from Miche to Puerto Rico in a big boat, wood with two motors, a big yola, like 80 people.

D.B.: That was your first time.

EDDIE: Yes, that was my first time. The second time I tried to go by the pier and I was gonna take a ship and the ship, it say on the top “Puerto Prince” but the guys with me they read it as “Puerto Rico”, so everybody say Puerto Rico ‘cos you could only see half the word. So I arrived at Puerto Prince. I remember that I thought it was strange here. I look at the people and I thought in Puerto Rico they don’t have so much black people and the language. I thought, oh, maybe I’m in Jamaica.

D.B.: So what did you do?

EDDIE: I spent six days there and I got to the border and I waited on the border, I waited there for two days on the border and then I crossed back again at night. I left Haiti at 10 o’clock and at 7 o’clock in the morning I arrived back again in the Dominican Republic. We were walking a lot. I remember the guide, we rented a house, I gave him 150 Dominican pesos or 14 Haitian pesos.

D.B.: How did you get the money?

EDDIE: I found a Dominican woman who had a beauty parlor and she gave me the money to get back.

D.B.: And the third time?

EDDIE: I had good luck. I took a tourist ship from here to Puerto Rico. That was good. I got into Puerto Rico the next day and when everybody gets out, I had like 7 dollars, I got a car and he put me in old San Juan. I met a guy on a bus and they put me off at Barrio Obrero and I met some guys I know from here and I spent a year there working and then I left for New York. I got some Puerto Rican papers and I was able to find somewhere to live on 109th and Columbus Avenue in Manhattan, and go to school at Booker T Washington and then Washington Heights School and I used to work on 32nd street, behind the bus station. (January 14, 2003)

Eddie provided details of the long, hard process to finally make it to the United States during the mid-1980s, before Homeland Security operations were established, before the border controls were tightened, and before a 700-mile wall to thwart the “illegals” was proposed. In our sample, approximately 25 percent of the respondents had made multiple crossings to the United States as undocumented immigrants, including a small number who now live in New York City (see chapter 11). How do they move back and forth? Obviously they can make it through this arduous route either by yola or as a ship’s stowaway to Puerto Rico, or over the Mexican and sometimes Canadian border via a coyote, but an easier way is to have false documentation. Eddie again describes how he solved the problem of having been caught and the inevitable recording of his illegal efforts.

D.B.: I don’t understand how you got back again and then returned. I mean you did it several times.

EDDIE: Well, I realized that I had to get out of the United States because of my situation. You know, as I told you, I’d went after this guy who tried to kill me. He shot me three times and left me for dead. You know, I was laying there and I said to myself I can’t let this guy get away with it. So I found him. I found him in New York and he paid the price. So now I thought well, I need to go back to my country. I need to get away from the city, from the U.S. and just get some peace. So what do I do? In this world there are lots of drug addicts and they die and no-one knows what’s happened to them. These guys have documentation, they have i.d.s, passports, and all kinds of papers. So that’s what I did, I took over somebody else’s identity. I used their Dominican passport that had a visa in it and I came and went. (January 14, 2003)

We have shown the beginning phase of the journey to the United States as the subjects remembered it. It is a complicated process, socially, culturally, physically, emotionally, and economically. Although tens of thousands make this journey as a matter of course in their lives, as a seemingly inevitable choice if they are to escape from ever-present danger or have any sense of opportunity, we should not underestimate the toll this takes on individuals.

The experience varies greatly and is contingent on a range of factors. Subjects who left as children remember, for the most part, the good things about leaving. They remember rejoining their families, having basic necessities such as food, electricity, and hot water just being there, seeing consumer items such as refrigerators and televisions (with real channels) that had been so scarce in their barrio now part of everyday life. For older subjects, the memories of their experience are influenced by whether they were able to enter the country legally or illegally. In the case of the former, their memories of leaving are cultural in nature as they had to deal with contradictory feelings of displacement and excitement, Caribbean heat and East Coast snow, the slowness of island life and the daily velocity of a “New York second.” For the “legals,” we will see in due course that the major experiences of their transnational journey come with settlement. For the latter, those who entered the United States illegally, their memories of the journey are quite different. When an illegal subject reaches the other side, there is enormous relief and hope and they set about the task of settling, of doing what they have to do to survive and to ensure that money is regularly sent home to their families. This obligation was of primary importance to them and was one of the most positive memories of their stay in the United States. In other words, they had experienced, for at least a short period in their lives, the ability to contribute to their families’ household income. This finding should not be underestimated because it bears out the truth in Maslow’s conception of the hierarchy of human needs, a truth that has been difficult to achieve within the post-colonial, dependent relations that always frame the Dominicans’ struggle for political and economic survival.