6

Cetasika

On the pink-flower

there is a white butterfly:

Whose spirit, I wonder?

—Lafcadio Hearn

A psychic unit is not ‘composed’ of rigid parts, arranged, as it were, in juxtaposition like a mosaic, but is rather a relational and correlational system of dynamic processes.

—Nyanaponika Thera

Another Accompanying Dimension

At about this point in my study, I started to experience the Abhidharma as a form of ancient art. Very old cultural artifacts are often patterned yet irregular, with a kind of multiplicity and mystery that is hard to describe. Studying the Abhidharma puts us in that same complex sea. Outsider art, by artists who are not traditionally trained, or folk art, often gives me the same feeling. There is a man who spends all day drawing pictures of downtown Chicago from the bridge over the Chicago River. He uses a ballpoint pen and spends hours on incredible detail, such as filling in rectangles of windows in office buildings. His reverence for intricacy brings the scene to life, as Abhidharma study can.

At this point the entire complexity of citta is moving into a new, also complex context. We are moving from the study of the atom, in the chemistry analogy, to the study of molecules. Every citta occurs nestled in a bed of supporting and enabling factors called cetasika (pronounced chay-tah-sika). Cetasikas are mental qualities that are more psychologically recognizable to us than the tiny unit of a citta event. They include emotions, ethical capacities, types of intelligence, and mental skills.

Every citta is accompanied and assisted by a grouping of these mental factors. There are fifty-two possible cetasikas, and anywhere from seven to thirty-six of them surround each tiny instance of human cognition. In 1960s psychoanalytic jargon, a “complex” referred to the larger-scale but similar idea that psychic processes occurred in constellations. The brain never fires one neuron at a time. Even on the tiniest scale, knowing is a conglomerate. “Even an infinitesimally brief moment of consciousness is actually an intricate net of relations.”55

Citta and Cetasika Are a Unit

In early Buddhist imagery the relationship between the citta and the supporting cetasikas was compared to a king and his court, or a hand and fingers that all coordinate to pick up an object. Cetasika could be compared to planets orbiting a star that is itself in orbit in a galaxy. The cetasikas are the subcontractors of cognition.

Cetasikas, or mental factors, accompany citta precisely; they arise together, cease together, share the same object and the same cognitive or perceptual base. They are conjoined—not casually connected—processes. Other processes affect or aid citta, but only the cetasikas move so exactly with the citta.

Categories of Cetasikas—The Universal Group

The cetasikas are grouped relatively simply, compared to the cittas. There are four main categories: seven universal cetasikas and six occasional cetasikas, which are all karmically variable; fourteen unwholesome ones; and twenty-five cetasikas that are wholesome, or beautiful. The term “beautiful” is used alternatively because these positive cetasikas may not necessarily be included in wholesome cittas.56 Some functional cittas (that don’t produce karma) are also accompanied by these useful and compassionate factors.57

The karmically indeterminate cetasikas (the universals and occasionals) take on the karmic quality of the citta they accompany, based on the entire grouping of the rooted citta and cetasikas. The seven universals accompany absolutely every instance of mental activity. They are: contact, feeling, perception, volition, one-pointedness, life faculty, and attention.

Contact here captures the sense of touch in citta, the impingement of the object into consciousness. Without contact there is no awareness or mental action. Contact is simply the coming together of the citta and the object in the appropriate consciousness field.

Feeling is, like the second khandha, a bimodal affective quality on this list. It is the simplistic kernel of reactive pleasure or pain related to an object. The word “feeling” is used in a basic way, almost pre-emotion. The complex emotions we notice in experience are actually formed of both the feeling cetasika and differing combinations of other cetasikas.

Perception as a cetasika is the noticing awareness of the bits and pieces of qualities of the object: the receiving of sensory impressions through sense organs, prior to any processing.

Volition on this small scale refers mostly to the cognitive intent to know, the rallying force of the cetasika group to help in the mental activity of touching the object. Volition is goal-oriented. This cetasika is the most karma-inducing, because of its directional bias. On the small scale of a consciousness event, will is simply a decision to meet an object, but the accompanying roots decide the valence of this goal.

The next universal, one-pointedness, is the tiny energy that fixes the mind to the particular object in the moment of citta, but it is considered the germ of the broader qualities of concentration or absorption that are trained in some meditations.

The mental life faculty maintains all the activities of the cetasika group, vitalizing the energy potential. It is the mental parallel to the general life faculty that sustains animate organic life.

Finally, the word for “attention,” manasikāra, in this group literally means “making in the mind” in Pali. It has an orienting job that yokes the mind to the specific object.

In other words, during every cognitive act, there is contact with the object, an accompanying affective tone, sensory perception, some motivated bit of decision to engage, a focus, a basic energy, and some selectivity. These are the universals, the givens of cognition’s support staff.

The list of universals can have a felt sense, although it is mentally microscopic. Two facets register in a perceivable way for me. One is the hierarchical nature of the cetasikas backing up the citta moment. These elements do seem to buttress raw cognition, like stone arches holding up a cathedral wall. The bare instance of knowing, surrounded by these factors, acquires shape and quality in the smallest experience. It’s as if the citta were moving in a transparent, gelatinous blob, in molds shaped by cetasikas.

The universals could be like a complicated sound control board. When I look at this spider on the windowsill, I dial up feeling and one-pointedness and then dial down the lever for contact as I feel aversion. When I check the clock on the wall, I dial up perception, but volition and life faculty might be lowered, as the clock has less hold and active interest for me than the spider did.

The list also works with the logic of necessity. Each item feels vital to consciousness. As discussed in the steps of perception, any moment of cognition does involve an object, does involve associations, does require some drive and focus. If there is no energy, no direction, or no reaction, there is no consciousness event. It falls apart. These items are all necessary in the live moment of consciousness.

The Occasional Group

The next group of karmically variable mental factors are the occasionals, which show up with cittas, depending on circumstances. The first two are called vitakka, or “initial application,” and vicara, or “sustained application.” Vitakka strikes at the object, mounts the object, directs the mind toward the object, while vicara is a continued and anchoring pressure on the object. In the commentaries these two mental actions are compared to a bee diving into a flower and a bee buzzing around it, or to a bird spreading its wings and one gliding in flight. Vitakka does not accompany the higher meditative states because it has been overcome by meditative development.58 The adepts enter at a higher, smoother state, or it may be that the state almost meets them halfway and they don’t have to reach for it so conspicuously.

Decision is the next occasional, which seems to be a development of volition in the universals. The Pali word here, adhimokkha, literally means “releasing the mind onto the object,” and it is not just a goal, but a resolution or a conviction in the object. Energy, the next item, like the universal item mental life faculty, marshals and upholds the moments of consciousness, but adds a kind of exertion and vigor to the moment, stirring it up.

Zest is an occasional cetasika, referring to the endearing and pervading refreshment experienced in contact with the object. This cetasika is striking and original. “Zest” in English rarely applies to the feeling of an action of consciousness. It is usually on a gross physical or sensual scale, referring to robust behavior or bits of lemon peel. But its application to a tiny mental moment rings and captures something very important about why we like to be conscious in the first place. Contact with objects is refreshing in a certain sense, which is readily discerned after deprivation of stimulation.

The last occasional is desire, which refers to the stretching to and longing for the object by the mind. This is not the unwholesome type of grasping desire, but more like zest, expressing the mind’s drive toward contact with reality.

It is easy to see how the karmically indeterminate cetasikas, whether universal or occasional, are relatively neutral functions. They acquire valence through association. The ultimate qualities of drive and focus, direction and energy depend on their roots, objects, and goals. Contact with the sound of a buzzer or contact with the sound of a wind chime have similar mechanics and opposite outcomes. The same quality of focus can be applied to an unhealthy obsession or an ethical and beneficial goal.

The Unwholesome Group

The unwholesome list of cetasikas follows the occasionals, and it needs no further introduction. Each item is distinctly painful or nonproductive. The list starts with delusion, meaning ignorance or concealing of true nature, which is the root of all unwholesomeness in Buddhist understanding. The items then tend to vacillate between ethical problems and psychological types of symptoms.

Shamelessness and fearlessness of wrongdoing follow and refer to a lack of repulsion or dread toward bad behavior; they are wisely described in the Abhidharma as being caused by lack of respect for the self and others, respectively. The next item is restlessness, agitation that makes the mind unsteady.

Then we return to the hub of human problems. The next item is greed, the first unwholesome root, referring to all manner of selfish desire, longing, and clinging. Wrong view is next, meaning presumptuousness and misinterpretation. Then there is conceit, which only arises in greed-rooted cittas. The meaning is broad in this context; it refers to a delusional and clutching stance toward the idea of self. Bhikkhu Bodhi’s commentary says plainly, “It should be regarded as madness.”59

The second unwholesome root, hatred, is also very broadly used and includes aversion, ill will, and annoyance. In this context, hatred is described as burning up its own support, the body and mind in which it arises. That is another buried Abhidharma gem of insight. Hatred does always harm the hater. Greed and hatred fuel each other, but they move in opposite ways: greed builds toward grasping while hatred results in a pushing away or destruction of the object.60

Envy, avarice, and worry (with a tinge of remorse) are next on the unwholesome list, followed by sloth and torpor, which always occur in a pair. Sloth refers to a sickness of citta, while torpor refers to a sickness of the cetasikas. The sluggish dullness and smothering quality of this pair in the Abhidharma description are very much like symptoms of depression.

The final unwholesome cetasika is doubt, or wavering caused by unwise attention. This circles back to the beginning of the list, with delusion as a basic deviation from wisdom. Doubt itself is not unwholesome in Buddhist thought; great doubt, in the sense of questioning, is considered a necessary quality of spiritual development. In this context, however, doubt is closer to obsessing or speculating without a solid frame of reference in experience.

The Beautiful Group

The positive list in the cetasikas is called the “beautiful” factors, which seems to be as much of a value judgment as “wholesome.” But again, that is a technical consideration to cover the fact that some good cetasikas are not necessarily supporting wholesome cittas. The beautiful list is a depth analysis of what works mentally, from kinds of cognitive intelligence to emotional and ethical stability. Most of this list is termed universal; nineteen of the twenty-five beautiful factors occur in all wholesome cittas.

The list starts with faith and mindfulness, which is a capacity for setting forth and a present and steady frame of mind. Shame, fear of wrongdoing, non-greed, and non-delusion follow, which are opposites of unwholesome items. Non-greed is described as non-adherence to objects, like a drop of water beading off a lotus leaf, and non-hatred has the quality of not opposing and removing annoyance and fever. These descriptions are powerful and visceral.

The next beautiful factor is neutrality of mind, which is not a lack of feeling or detachment but a kind of developed balance and impartiality. The literal translation from Pali, tatramajjhattatā, is “there in the middleness,” where so much of life can be found.

The next two items take two beautiful factors and expand them to encompass all living beings as objects. On this absolute scale, they are known as Illimitables. They are loving-kindness, which starts with the seed of non-hatred, and neutrality of mind, which generalizes from equanimity. The other two of the four Illimitables are coming up at the end of this list.

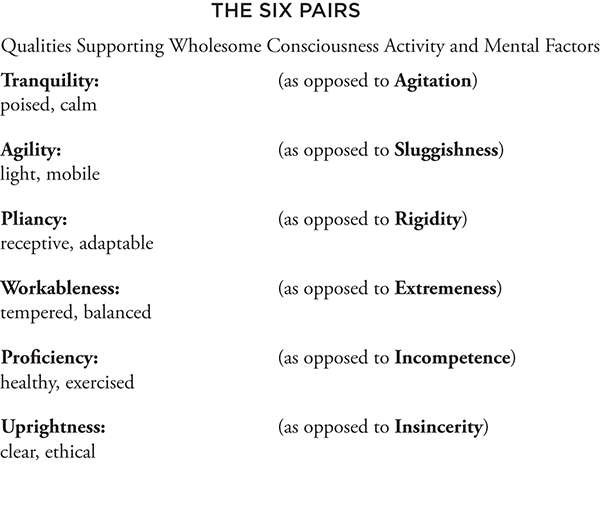

But first, to complete the nineteen universal beautiful factors, are six pairs of mental skill items. They are called pairs because they can exist both as qualities supporting the central citta itself and as supporting the entire group of co-occurring cetasikas, like a director who is also a cast member in a play. In one role she is central to all activity, and in the other she just adds her particular character to the mix.

This list could be considered a perfect definition of intelligence. To cultivate these six qualities would be to develop the best of what is possible of a human heart and mind. It wraps up the list of universal beautiful factors and gives us a sense of how powerfully complex and balanced a moment of wholesome citta must be.

The last six beautiful factors occur as needed. First are three abstinences, which arise with deliberate refraining from an opportunity. They are termed right speech, right action, and right livelihood, which are also the three most behavioral items on the Eightfold Path, the Buddhist prescription for relief of suffering. These three items together resemble will power. They provide energy for successful restraint backing up a moment of conscious contact. Maybe they describe the feeling of looking at a person at the moment you hold back a critical comment or avoid acting in an opportunistic fashion.

The last two Illimitables, or immeasurably dispersed qualities—compassion and appreciative joy—show up next. (The first two are loving-kindness and equanimity, which are extensions of non-hatred and neutrality of mind on the universal beautiful factors list.) These are two brands of empathy, the quality of wishing to relieve the suffering and bolster the success of all beings. These qualities do not evolve into internal, personal sorrow or cheerfulness; they simply connect with others’ feelings. Finally, the last beautiful factor is an apt closer: non-delusion, or wisdom, the illumination of or penetration into true nature.

Mental Factors as Another Dimension

The cetasika list seems a bit less centrally organized than the citta list, which progresses with a developmental logic. Within the four major cetasika categories, items bounce between qualities that could be more neurologically based, like mental agility or attention; emotionally defined, like envy or zest; or interpersonally trained, like right speech or shamelessness. The general sense of the unwholesome versus the beautiful qualities might be seen as consciousness touching an object with basic grasping versus touching it with openness and love.

I have tried to think of a mental quality that supports consciousness that is not on the list and have failed. Descriptions or combinations may differ, but the Abhidharma thinkers seem to have caught the pieces of the human cognitive puzzle. The mental factors can combine to describe almost any possible psychological state. The dimensions they add to the plain citta give us a descriptive handle on even minute instances of conscious experience.

When the cittas and cetasikas started to combine in my mind, the deep artistic sensibility of the Abhidharma took hold. Considering all these qualities interacting, giving raw, conscious experience direction, contour, and color, I feel something like what I feel seeing old, handmade beadwork. Everything is inexact but intricate. The mind savors the rhythms and nothing is left out.