GUNS OF THE SETTLERS

CHAPTER 4

The writings of Hemingway and Robert Ruark might leave the impression that if the white settlers did not harry the game of British East Africa exclusively with Holland & Holland .465 doubles and .416 Rigby magazine rifles, they at the very least had the decency to use a .404 Jeffery, a .318 Westley Richards, a .375 or .300 H&H Belted Magnum, or a shockingly big-bored .505 Gibbs.

Unfortunately, it really was not so. Kenya did have more than its share of lords, baronets, and belted earls, and even had a noble duke or two, but the great majority of the settlers came from very different backgrounds. They included Boers who, finding that South Africa had grown too civilized, had taken a ship to Mombasa and then trekked inland from the railhead with their ox wagons; soldier/settlers who were given land for service in World War I; men like my father who had the guts to break free and start over; and the adventurers who in their love of excitement and disdain for the restrictions of civilization have always been drawn to the frontiers. They were a hardy and self-reliant breed, stubborn and independent-minded to a fault (Sir Winston Churchill, who visited Kenya when he was Great Britain’s colonial secretary, remarked that everyone he met seemed to be the leader of his own political party), but they were never boring.

Kenya’s settlers had one thing in common—each was chronically short of cash. When the newly planted coffee trees bore fruit, or when the herds of imported cattle and sheep matured, or when the wheat was harvested, they were rich. But then a two-year drought, or an outbreak of rinderpest or wheat blight, or a swarm of locusts that darkened the sky like the smoke of a brush fire would disdainfully wipe out all their work and their fine plans and they would have to start once again, rebuilding from scratch.

Yngvar Aagaard with two lion he shot with the 7x57 Mauser, circa 1928.

Few of these men were trophy collectors or firearms hobbyists. Their guns were simply tools used to put meat on the table and to protect their crops and livestock, and occasionally their lives. Many of them owned but one centerfire rifle that was expected to do it all. Price, under those circumstances, was an overriding consideration in their choice of such a gun. So was the cost of ammunition.

My father used to tell, by way of an example, that when Karen Blixen, who later established world renown under the pen name Isak Dinesen, left Kenya, he was given the opportunity to buy her .318, and at a very reasonable price. He turned it down because the ammunition for that rifle was as expensive as the rifle was cheap, and he simply could not afford it. (My father wore out the barrel of his 7mm Mauser shooting at game animals, not at paper targets.)

Consequently the guns they tended to use were Mauser, Mannlicher-Schoenauer, and Lee-Enfield magazine rifles (and, after World War II, Belgian F. N. Mausers or Czechoslovakian Brnos or Swedish Husqvarnas), often in calibers such as 6.5x54mm, 7mm and 8mm Mauser, 9.3x57mm, and of course .303 British—cartridges that most of us today would consider rather inadequate for the work. A well-known American hunter and writer once asked me why anyone would go after elephant with a .303. The answer is because that is what they had. A typical settler might buy his two elephant licenses a year and hope to make a little profit from the sale of the ivory, but he could not justify the expense of an extra, specialized heavy rifle just for that purpose. Being innocent of ballistics theory, and having read none of the right books, he would go ahead and stick a 215-grain .303 “solid” into the elephant’s ear-hole or lungs and, finding that the creature died, would reckon he had a fair enough gun for hunting elephant.

Around the turn of the twentieth century several nations adopted 6.5mm-caliber military rifles. Sportsmen tried them on game and liked their light weight, handiness, and lack of recoil. Thus gunmakers such as W.J. Jeffery were soon turning out sporting rifles, based on the Romanian Model 93 or the Dutch Model 95 Mannlicher military arms, chambered for the 6.5x53R, a rimmed cartridge that developed some 2,350 fps velocity with 156-or 162-grain roundnose bullets. With their great sectional densities, these long bullets usually gave deep penetration and dependable killing power even on large animals—provided the shots were properly placed.

The 6.5x53R, together with the ballistically similar but rimless 6.5x54mm (introduced as the Greek military cartridge in 1900 and for the Mannlicher-Schoenauer sporting rifle of 1903), quickly became popular with British big-game hunters. They tended to refer to both cartridges indiscriminately as the “.256 Mannlicher” or simply as “the Mannlicher.”

Some of these men did not hesitate to use their Mannlichers on the largest of African game. Capt. C. H. Stigand, a very experienced African hunter/naturalist and governor of the Mongalla province of the Sudan who was killed in a fight with the rebellious Dinka tribesmen in 1919, apparently preferred “the Mannlicher” to anything else, even for elephant.

Stigand did recommend having a heavy-caliber double rifle along when hunting dangerous game, provided one had an absolutely reliable gunbearer who could be counted on to stand firm and hand it to him in the event of a charge.

“Otherwise,” he wrote, “I have then found it best to trust entirely to a magazine small bore, as with such a rifle you practically always have a cartridge ready, whilst with a double bore you generally expend both cartridges . . . and then a critical delay takes place while the gun is reloaded.

“For elephants,” he continued, “I sometimes take a big bore from the man carrying it, when the animals are located, and advance with a rifle in either hand, subsequently resting the big bore against a bush whilst I fire with the small bore.”

The best-known exponent of the small bore on large game, W. D. M. “Karamojo” Bell, is famous for having taken several hundred elephant with a 7x57mm Mauser. But he also tried a 6.5mm Mannlicher-Schoenauer for a while and had a long-barreled .256 Mannlicher that had been stocked and sighted for him by Gibbs. This latter he used with softnose bullets as a meat gun to feed his numerous following, and to obtain hides for footwear, donkey saddles, and for barter.

“And what a deadly weapon it was!” he wrote in Karamojo Safari. “I have known it to lay out a score of antelope from one anthill stance.... I don’t think that even now a better rifle could be found for that particular work. . . . It projected a long heavy bullet at a very respectable speed . . . and it performed well at long ranges, as, for example, on giraffe.”

Sir Alfred Pease, a well-to-do Kenya settler whose invitation, it is said, initiated Theodore Roosevelt’s expedition, hunted lion extensively on the Athi plains and wrote The Book of the Lion, still a respected work on the subject. Sir Alfred preferred to use a light, handy rifle and keep the double-barreled “ball and shot” gun in reserve when hunting lion.

His favorite rifle was “...a rather short-barreled, five-shot-magazine .256 Mannlicher; any apparent deficiency in size of bore and weight of bullet is compensated for, in my opinion, by the ease and rapidity in which it can be manipulated, the little room occupied by ammunition, the flatness of trajectory, and the superiority of its striking energy over some large bores.

“With the .256 I have killed many lions as well as pachyderms, and antelopes from greater kudu downward . . . facing a ferocious lion I have felt quite comfortable with my .256 Mannlicher in my hand and a 12-bore gun, loaded with big shot, cocked on the ground between my feet.”

Early buffalo taken with Finn’s old .375.

Quite so, but it should be borne in mind that Sir Alfred hunted, for the most part, on open plains.

By the time I was growing up, the Mannlicher rifles with their pendulous magazines and en bloc cartridge clips were about extinct. But Mauser sporters chambered for the 6.5x58mm Portuguese round, with its 157-grain bullet at 2,570 fps, were seen often enough, and 6.5x54 Mannlicher-Schoenauer carbines and half-stock rifles were still popular with resident hunters, farmers, and ranchers. In fact, as late as 1970, one of the chaps I knew at Juja Farm (where Roosevelt hunted as a guest of his friend William Northrup McMillan) was still using a long-barreled 6.5mm Mannlicher-Schoenauer to bash marauding lion and crop-raiding hippo.

Another chum, best remembered simply as Mike, acquired a Mannlicher-Schoenauer carbine while he was managing a large ranch in the RiftValley. One of his duties was to shoot a score of Grant or Thomson gazelles, or the equivalent in kongoni (Coke hartebeest), every week. This was a government-sanctioned “harvesting” of surplus game, in the true sense of the word. It was not sport, but just an unpleasant and dirty chore to be taken care of as quickly and efficiently as possible. Mike did it at night, shooting by spotlight from an open Land Rover.

Once, while I was spending a few days with him, a couple of newspaper reporters from Nairobi visited the ranch to see this cropping operation. We took them out that night, and the first herd we got into, Mike handed one of them the carbine and told him to have at it. His employer had provided Mike with a lot of old ammunition, and the first shot was a hang-fire that went off quite some time after the firing pin had clicked, as the reporter was lowering the butt from his shoulder. The second went, as had the first, in the general direction of the moon. Exasperated, Mike grabbed the gun and demonstrated how to do it. The carbine said, click . . . boom! five times in rapid succession, and each time it was answered by a thump as another Granti went down.

“That’s the way,” Mike explained. “All you have to do is keep the sights on the animal after you’ve pulled the trigger until it finally goes off—nothing to it.”

But the poor reporter was so unnerved that he nonetheless flinched wildly every time, leaving Mike to shake his head in disbelief at the notion that any man, even a city slicker, would let a little thing like that upset him so.

One of the students at Egerton College, a product of Eton whom we nicknamed “Handsome” because he was good-looking—though we did not mean it as a compliment—also had a Mannlicher-Schoenauer, a special-order carbine. It had the usual double-set trigger and open sights, and was also fitted with a scope in European quick-detachable mounts. The scope was mounted very high, so prior to using it one pressed a button on the underside of the stock, whereupon a spring-loaded cheekpiece would jump up to provide a suitably high comb—a seemingly nifty arrangement.

Once, when we were out together, Handsome got ready to shoot an impala at fairly long range. He snapped the scope into place, set the trigger, brought the piece to his shoulder, and then realized that he had forgotten to raise the cheekpiece. So he lowered the rifle and pressed the requisite button. The slight vibration as the cheekpiece sprang up into place was enough to jar off the hair trigger, and, to everyone’s considerable consternation, the gun fired. Whenever I hear of some new and wondrous gadget that is going to revolutionize riflery, I remember Handsome and his marvelous Mannlicher.

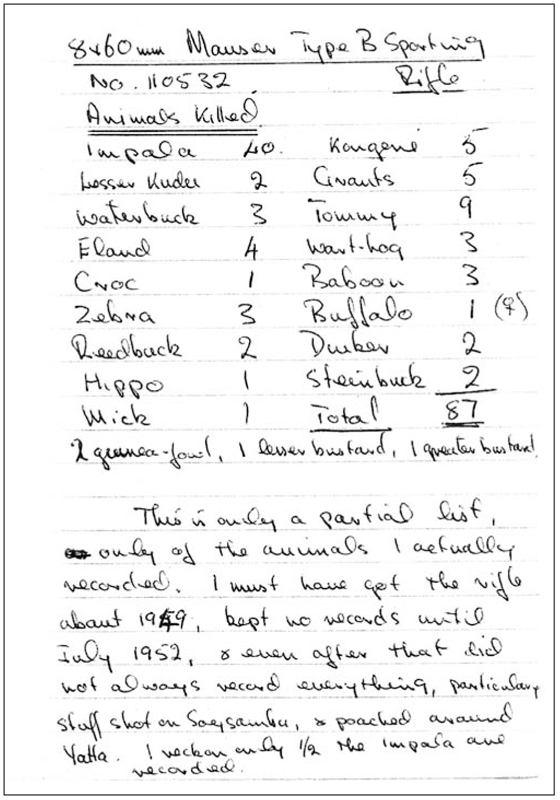

Note the use of the word “Mick,” which was slang used in BEA for Mau Mau terrorists.

The following is an entry in Finn Aagaard’s diary near the list of game he shot with the 8x60.

17 Feb 1962

I bought a third-hand BRNO .22 Hornet off Mike Drury. Took the old .22 BSA into Wali Mohamed to be sold, and handed in the old 8x60 to be destroyed by the police, so now I have only a .375, a Hornet, and a .455 revolver.

Getting rid of the 8x60 was rather a wrench. Uncle Bernhard looted it out of Abyssinia during the war, and I had carried it for many years and all through the Emergency, except when I was in the Kenya Regiment.

It killed everything from guinea fowl to buffalo, including a lot of impala, quite a few zebra and waterbuck, a Mau Mau, and three or four eland. But I could no longer hit anything with it, and it was unusable. (It was marked “Mauserworks A. G. Oberndorf A/N.” Serial # 110532.)

One of the other students owned a vintage 8x56mm Mannlicher-Schoenauer rifle. It used a 200-grain bullet at a listed 2,200 fps, and to the best of my recollection it killed the various antelope as well as anything else, though it was obviously no long-range outfit. Mike Williams had a sporterized Mark III Lee-Enfield in .303 British that had been fitted with a decent pistol-grip buttstock. In it he quite frequently used military 174-grain full-metal-jacket ammunition that he obtained from a local policeman. Despite the belief that such ammunition is totally unsuited for hunting, it seemed to bring game down quite satisfactorily when the shot was placed at all properly.

Although there must have been quite a few in use, I never came across an 8x57mm Mauser. The 8x60mm was quite popular, though. Apart from mine, John Fletcher, also at Egerton, had a Brno in 8x60 and several of my father’s friends owned them. One I remember particularly well was a much-used but cared-for English-style Type A Mauser sporter fitted with an express sight with four folding leaves, a single-stage trigger, a magazine floor-plate release in the trigger-guard bow, and a horn fore-end tip—a beautiful rifle. The cartridge was developed to circumvent a ridiculous restriction, part of the Versailles Treaty, on the ownership of 8x57mm rifles in Germany. An 8x60 reamer, which oddly is only 2mm longer in the case body than an 8x57 (the neck is 1mm longer too, bringing the overall case length to 60mm), was run into the chamber of an otherwise illegal 8x57mm sporter, and presto, it became a legal 8x60mm! For some years after World War I, Mauser produced no sporting rifles in 8x57mm, chambering them for the slightly better 8x60mm instead.

The 7mm Mauser was always a well-liked and effective cartridge, and the 7x64mm Brenneke, whose performance is almost identical to that of the .280 Remington, became quite popular in later years. I did not encounter many .30-06 rifles before I started guiding hunters, but one of my pals used a prewar Mannlicher-Schoenauer so chambered that bore only a “7.62 x 63mm” marking to indicate its caliber. John Bushmiller, the American barrel maker who spent some years hunting in Tanganyika, rebarreled a 9.3mm Mauser to a .30-06 for Peter Preston, a Kenya Regiment buddy of mine who had taken him out after forest elephant in the Aberdare Mountains. With its heavy 26-inch barrel, the rifle was no featherweight, but it shot wonderfully well.

While at Egerton College I wandered into the gun store in the nearby town of Nakuru with a Police Reserve paycheck burning a hole in my pocket. In the shop I spotted a dandy little Brno .22 Hornet bolt-action sporter and immediately bought it. Shortly thereafter, Brian Verlaque found a Weaver B4 telescopic sight lying in the grass on Menengai Mountain; the rings on it exactly fitted the integral bases on my little Brno, so he gave it to me. I thought it would make a perfect rifle for chasing the Mau Mau in the Mau forest, but though I did carry it on several patrols, I never fired it in anger. Instead I used it for gazelle and impala on the vast Delamere Ranch at Elementaita, where we had permission to hunt. I found it very reliable on those animals and a delight to carry. But at any range past a hundred fifty yards the slightest breeze would drift those short little bullets far off course, which rather limited its usefulness on the open plains.

Eventually I gave it to Dave Watson-Cook, a fellow Egerton student who was going off to pioneer some virgin land at Mau Narok, on the border of Masailand. There he built himself a couple of mud-and-wattle, thatch-roofed huts to live in, cleared and broke his land, and planted his first crop of wheat. Dave fed himself on bushbuck and duiker taken with the Hornet, and when hordes of zebra swarmed into his greening fields he used the little gun to drive them off. How many zebra and waterbuck he killed with it I do not know, but it was several score. He would place the bullet into the neck or, from broadside, through the ribs close behind the shoulder into the lungs, after which the zebra might run fifty or a hundred yards and then go down. One of Dave’s henchmen, a Masai, carried a club with a huge nut from some earth-moving machine for a head. He was awesomely proficient with that weapon, using it to dispatch a crippled zebra or any cur dog that came snarling at his heels, with what appeared to be a flick of his wrist.

Dave claimed he lost very few zebra, but did find that RWS and British ICI ammunition gave getter penetration than the American stuff, whose bullets were properly designed to set up on small varmints. Later he terminated the depredations of two leopard that were killing his sheep. He sat up for them at night with a spotlight and, when they came by, slipped a Hornet bullet between each pair of glowing eyes. He also killed a buffalo cow with it, though even he admitted that was taking a .22 Hornet a little out of its class. When the buffalo got up out of some brush and went lumbering directly away from him, he could not resist the temptation and gave it a bullet to the back of the head. The great beast collapsed in mid-stride but lay kicking, so Watson-Cook hurried around in front of it and shot it again in the middle of the forehead, and then it was quiet.

Several years later I got another Brno Hornet, but this time I dug around to find out exactly what its bullets achieved and kept notes on its performance. I found that within one hundred fifty yards or so it did a fine job on animals such as Thomson gazelle, duiker, and steenbok that did not weigh much over sixty pounds. It was also adequate for neck shots and broadside shots on impala, Grant gazelle, and other antelope of up to around a hundred fifty pounds live weight, again provided the bullet was placed exactly right and avoided the shoulder bones and the shooter avoided any angling shots. I also came to realize that it was simply stupid and irresponsible to try to make a pipsqueak little varmint cartridge work on big game, and I stopped doing that.

In fact, most of the settlers did use somewhat more suitable cartridges for the big stuff. The mother of one of my schoolmates presented his father with a used .425 Westley Richards, because she wanted to keep him and did not like his going after cattle-killing lion at night armed only with a .303. Many years later I acquired that rifle, which I had rebarreled to .458. The original 28-inch barrel was marked “Made for Newland & Tarleton Ltd., Nairobi,” one of the first safari outfitting firms. My friend’s father had bored holes through the fore-end and through the genuine horn fore-end tip so that he could clamp a powerful flashlight under the gun for night work.

Many of Kenya’s settlers liked the 9x57mm Mauser, whose ballistics were very close to those of the modern .358 Winchester, and considered it a fair lion gun. The 9.5mm Mannlicher-Schoenauer, often called the .375 M-S, had some following. It used a 270-grain bullet at only 2,150 fps, in the Kynoch loading. The 10.75x68mm Mauser, with a 347-grain bullet at 2,200 fps, also saw some use, despite its frightening lack of penetration, while the 11.2x72mm had an even worse reputation in that regard and was seldom seen.

Among the best of the family of 9mm Mauser sporting cartridges was the 9.3x62mm. Joe Cheffings, whom I first met upon my return from military service with the Kenya Regiment and who became a boon companion, friend, and partner, was provided by his employer with a 9.3x62mm F. N. Mauser, though he later traded it for a .375 H&H. Since Joe and I spent most of our spare time hunting together, I had ample chance to see the 9.3x62 at work. The cartridge drove a 285-grain bullet at 2,360 fps, just a bit better than could be had from a .35 Whelen—which was a wildcat cartridge in those days—even in the hottest handloads. When used in a workmanlike manner, the 9.3x62mm was effective, even on buffalo and elephant. The cartridge enjoyed such a good reputation that after the .375 was established as the minimum caliber, those who already had rifles chambered for the 9.3x62 were allowed to continue to use them.

Of course, there were quality English rifles in use as well. Fritz Walter, who managed the ranch adjacent to ours, was given an old and well-worn Rigby .400-350 by his employer. It used a rimmed .400 Nitro case necked down to hold a long 310-grain, .35-caliber bullet, which it shoved along at barely 2,000 fps. Fritz used that .400-350 on everything, including buffalo, and swore by it. One friend had a Holland & Holland Royal double-barreled .465 Nitro Express, another had a Cogswell & Harrison .375 H&H “magazine” rifle, and a third, whose father was a fairly affluent lawyer, used a William Evans .450 Nitro Express double, but that was about it among the chaps I hunted with, except for Willie Andersson’s big gun.

Willie Andersson, a close friend of my father’s, had brought a Husqvarna double rifle out with him from Sweden. The gun was chambered for the 9.3x74R, a ballistic twin to the rimless 9.3x62mm cartridge. To my father and his buddies it seemed a monstrous great cannon, and compared to their 6.5mm, 7mm, and 8mm rifles, I suppose it was. Willie bagged a few buffalo with it, but the first and only time he took it after elephant, the tusker he plinked promptly charged him. Willie turned and ran, and did not pause until he was back in camp. Thereafter the Husqvarna was always known as “Willie’s elephant gun.”

With the publication of the 1958 decree regarding minimum legal calibers for large game, Shaw & Hunter, the famous Nairobi gun store, imported a batch of Winchester Model 70 bolt guns chambered for the .375 H&H. They sold like hotcakes, and soon most of my hunting companions had one. They were good guns too, though not as well finished as some pre-’64 Model 70 aficionados would have us believe. In fact, they were quite rough; mine had to have the feed ramp smoothed before it would function with roundnose softpoints such as the 300-grain Kynoch. Nor was the stock bedding anything to brag about. The recoil lugs were seldom in proper contact with the wood, and consequently every single one of these rifles with which I have been familiar has split its stock sooner or later. When that happened, we glued them back together, cross-bolted them with stove bolts or whatever was handy, and bedded them in fiberglass from an auto-body repair kit. Then they held together rather well.

A young Peter Davey and big male leopard taken with 7x57. December 1960.

The .375 H&H quickly became the standard large-game cartridge among Kenya’s resident hunters. Though popular, the .458 never caught up with it because of the .375’s superior versatility. A lot of chaps chose to simplify things by having only one big-game rifle, a .375, and using it on everything. For that purpose there is still nothing else that can come close to matching Holland’s great old round.

Much else changed around that time. Imperial Chemical Industries ceased the manufacture of its Kynoch brand of centerfire sporting rifle ammunition, thus killing off the whole array of British sporting cartridges (except for a few such as the .404 Jeffery that were also manufactured on the Continent and those that had been adopted by American manufacturers) in one fell swoop. With the exception of the everlasting 7x57 and some others, the old Mauser cartridges also faded from the scene and were replaced by the .30-06, the .270 Winchester, and the 7mm Remington Magnum, with the .300 Winchester Magnum coming on well at the time of the hunting ban. They are fine cartridges, all of them, but the truth is that they are really not all that much better than their Mauser predecessors.

I had the great good fortune to be in the East Africa game fields in their heyday and thereby the opportunity to see how a great variety of cartridges performed on all manner of beasts. When I think back on it and browse through the journals I have kept since 1956, one inescapable fact emerges. Within reasonable limits, the choice of cartridge is not all that important. Whether a gnu is thumped with a 6.5mm, a 7mm magnum, an 8x60, or a .375 H&H seldom makes a noticeable difference. It will run about as far when shot through the lungs with one as with any of the others. Even today, as it always has been and ever will be, it is not the rifle or its cartridge that matters so much, but rather the skill and knowledge of the rifleman–hunter who is using it.