HAPPY SAFARI

CHAPTER 13

The late Leonard S. Burke, a tall, dark chap from Houston, Texas, had a warm, friendly, and delighted grin on his face when we met him at the airport, and to the best of my recollection he stopped smiling during the next three weeks only to laugh. He was on holiday, in Africa, and by gosh, he was going to enjoy himself. Petite Connie Burke, who, make no mistake, possesses a core of steel, was equally friendly and smiling, and the auguries promised a good safari.

Connie did not then hunt, and so Berit, who was seven months pregnant, came along to keep her company, leaving our first-born, Erik, with his grandmother. We camped in a grove of tall, wide-spreading, yellow-barked acacia trees close to the southern Uaso Nyiro River in Masailand, a spot from which we could hunt both the Loita Plains and the more wooded country above Narok. It was beautiful country with an entirely delightful climate. Due to its six-thousand-foot elevation and the constant breeze, it never got over eighty degrees Fahrenheit on the hottest day, while the evenings were cool enough that a jacket by the campfire and two or three blankets on the bed felt good. The hyena whooped madly—that most African of night sounds—and not uncommonly one awoke to a lion rumbling hoarsely somewhere in the distance.

Len had never previously hunted any four-footed game larger than a rabbit, but he had persuaded a knowledgeable friend to coach him in rifle shooting and had practiced a good deal at the range before he came. He shot the .30-06 Winchester we had hired for him very nicely when we checked its zero the first afternoon in camp, and he proved that he could adequately manage even my scope-sighted .375, which he was going to use for dangerous game. Besides that, he seemed willing to listen and to do as he was told.

Len Burke, happy hunter with good Grant gazelle.

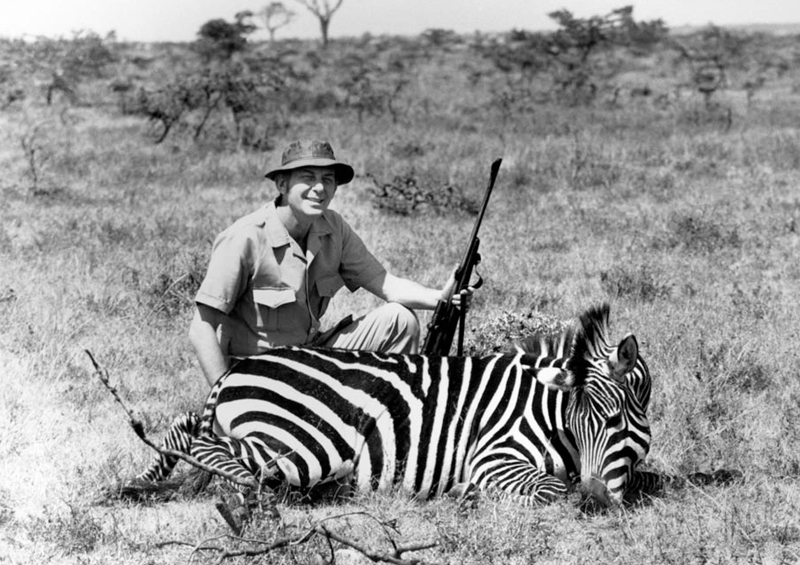

The first morning, we stalked a group of zebra on the Loita Plains until we had a clear shot at a small, black-striped stallion. Kinuno put up the crossed shooting sticks to help support the rifle, and we clearly heard the bullet strike. The stallion broke into a dead run, however, so I sat down with the .375 and got another bullet into it, rather far back through a kidney. As it turned out, it was not needed because Len’s shot had been in the lungs, but he had a horror of losing wounded game and had asked me to collaborate whenever I thought it might be necessary, a commendable attitude.

Berit, Kinuno, and I had the zebra skinned in short order, and we put most of the meat in the Toyota as well, to use as leopard bait. Then, after a cup of tea and cookies from the chuck box, we wandered on over the rolling, grassy plains until we spotted a herd of Grant gazelle feeding in a patch of whistling thorn. This low, scrubby acacia bears a profusion of round galls about the size of walnuts, in which live colonies of pugnacious ants that swarm out to defend their host whenever the bush is disturbed, a perfect example of symbiosis. When the wind blows across the ants’ entrance holes in the galls, a wavering, mournful whistle may be heard. In any case, the thornbrush would offer some cover for an approach, and because there were several large bucks among the gazelle, we left the vehicle and made our stalk.

Granti are among the largest of the true gazelles, with a mature buck weighing 150 to 175 pounds, and I think the handsomest of them all. The light fawn of their coats contrasts with their white bellies, black-outlined white rump patches, and chestnut-and-black-streaked faces, while their long, strongly ringed, flared horns sweep to an impressive height above their neat, short-muzzled heads. Eventually we got within 150 paces of the bunch, and after some maneuvering got a clear shot at what I had judged to be the biggest buck, when it hung back momentarily clear of the mob. This time no collaboration was needed, as Len drilled it precisely through the center of the shoulder area.

Len with nice impala.

Over the next few days we continued to hunt the so-called “plains game,” collecting wildebeest, Thomson gazelle, and a second zebra, and also hung leopard baits. While looking for a suitable tree in which to place a bait, we happened on a very big impala and went after it, leaving Connie and Berit in the Toyota. It led us in circles, and presently they saw Kinuno and me cross an open aisle in the brush. Len appeared close behind, but suddenly froze, and then started dancing about and slapping at his legs. He hurriedly unbuckled his belt and tore his trousers off, and frenziedly tried to brush something off his long legs. He had stepped into a column of safari (or driver) ants and literally had ants in his pants. That finished the impala hunt, and the girls were still giggling uncontrollably when we got back to the vehicle.

Some days later we had a customer at one of the baits. We built a blind thirty yards from it in a clump of brush, with a solid support for the rifle in front of the shooting hole. While Kinuno, whose dark face was less likely to be spotted, kept watch, Len and I lay back with a book each. The minutes dragged by while the sun slowly sank toward the horizon, until Kinuno suddenly grasped my knee. There was a leopard on the feeding branch, glowing black and gold where the dying sun illuminated it. It looked small and somehow feminine. “M’ke?” I breathed in Kinuno’s ear. He nodded agreement that it was a female. It was legal to take females, but we by all means avoided doing so. It would have been a horrible tragedy to shoot a female, find she was in milk, and realize that one had left a litter of little cubs to starve. Len was staring inquiringly at us. I pointed toward the shooting hole and whispered, “Female. Take a look, but do not shoot.” As we watched, the leopard looked down and gave a strange, soft call. The brush at the foot of the tree stirred, and a half-grown cub scrambled up to join its mother. We stayed until black night, and the next day we replenished the bait so that Connie and Berit could watch the show. But when, a couple of evenings later, we sent the camp staff to see them, the leopard did not come. It turned out that the carnivorous safari ants had found the bait and were swarming so aggressively over it that the cats had surrendered it.

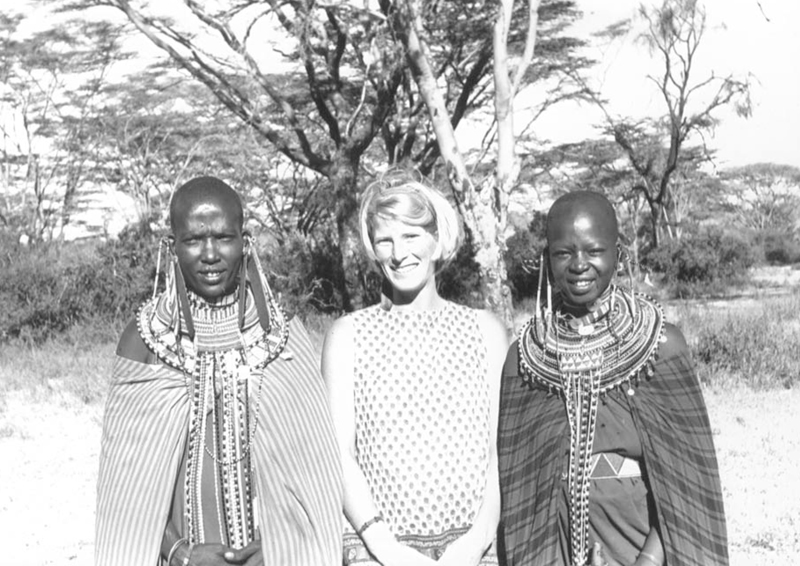

Berit with pregnant Masai women.

A constant stream of Masai visited the camp to look at the white people and be amused by their strange and utterly incomprehensible ways and customs. They would seat themselves hopefully by the kitchen fire, and presently Nzioka, the cook, would offer them a cup of hot, sweet, milky tea, as was only proper (he did limit them to one cup each per day, though). Nzioka had a gift for languages; he spoke some Swedish and Italian through having worked for families of those nationalities, and he could get along quite well in Masai, although it was as different from his native Kikamba as Russian is from English. One day he asked us whether the wageni (foreign guests) would be interested in photographing two Masai women. For five shillings each they would come back next day and pose dressed in all their finery. The bargain was struck, and the two ladies showed up decked out in beaded leather petticoats with ochre-dyed cotton shukas knotted over the right shoulder, and surmounted by patterned cotton shawls. They wore wide, beaded belts, beaded ear ornaments, and around their necks overlapping tiers of beaded collars from which long strings of bright beads dangled down to their knees. Around their wrists and ankles brass bangles gleamed against the dark skin, and the younger, a cheerful, smiling lass, carried a beaded and decorated gourd of curdled milk. The gourds are rinsed out with cow urine and smoked before the milk is allowed to stand in them and curdle, which gives it a characteristic flavor. If one can overlook the odd dead fly, it is very good, refreshing stuff. Karamojo Bell swore by it, and said that together with dried, smoked elephant meat it formed the perfect diet for an active elephant hunter.

Both the women were equally as pregnant as Berit. They gently patted her stomach in approval, and insisted that the three of them should be photographed together. Berit stood with her hands behind her back, but that would not do at all. They took her hands and showed her that she should clasp them demurely in front of her, as if everyone ought to know that was the only way for a lady to pose.

Peter Davey brought a friend of Len’s down for a couple of days. Ron worked for an airline and happened to be in Kenya on a short trip. While Len and I were beating the brush for a bushbuck or some such, Pete and Kinuno took Ron out to see if they could get him a Thomson gazelle. They chased a likely specimen all over the wide-open plains, and finally Ron crippled it. Pete took a shot at it with my .375, but missed. The little gazelle (they weigh perhaps sixty pounds on the hoof) was running directly away, and the range was increasing every second. Pete passed the rifle to Kinuno and told him to try. Kinuno sat down, rested the fore-end on the shooting sticks, grimaced in concentration, and shot it perfectly through the heart from the tail end. So much for the great white hunter!

Len and I got our bushbuck, a smallish one, and spent a whole morning trying to get a shot at a very handsome 27-inch impala. It lived at the edge of the brush surrounding a large open plain. We tried to approach it by the easy and obvious route, but every time we got nearly in range something went wrong—the wind gave us away or we ran out of cover and were spotted. We knew that petty soon, if we kept disturbing it, the buck would move out altogether, so we backed off, made a big circle that took us about an hour to complete, and crawled up on the impala from a totally different and unexpected direction. That worked, and Len made the most of a broadside opportunity at 226 long paces by hitting it through the center of the chest directly above the foreleg—perfect placement.

I reckoned he was ready for buffalo, so dawn one morning saw us hunting along the edge of the 500-foot-deep gorge of the Siapei River. Buffalo herds often grazed the river flats way below. We saw none this day, but around midmorning we found a lone buffalo bull on a bench about halfway down. As we watched, it ambled into a patch of shady trees and brush, probably to bed down until the cool of the evening. We went back half a mile, scrambled down to the bench, and carefully stalked the mott of brush. Skirting around it, tense and adrenaline-charged, we peered hopefully into the cool, dense, black shade. Kinuno caught a swish of its tail and pointed. Gradually we made out the black form and decided which end was which. I nudged Len and mouthed, “Shoot!” With the 2.5X scope Len had no trouble seeing where to hold. At his shot the bull turned and lurched away deeper into the thicket. I tried to get a .458 bullet into it, but through my iron sights it was indistinguishable from the dark shadows, and I did not do much good. Fortunately Len had hit it reasonably well, and some minutes later we were relieved to hear its sad death bellows. The toughest part was getting the head, the cape, and as much of the meat as we could manage back up the sheer wall of the gorge to the top.

Len with his elephant.

Then we went bird hunting. Len, who enjoyed the shotgun, spent an afternoon with the doves and flighting green and olive pigeons, while Berit bird-dogged for him. That evening he marinated the breasts in a sauce he and Nzioka concocted, and broiled them on a grill over the embers of an acacia-wood fire—superb! It was decided that Connie should try to bag a few of the numerous guinea fowl. I don’t think she had ever pulled a trigger before. We found a large flock of guineas busily engaged in scratching around in the dust. A convenient big bush provided cover. I put Kinuno in the lead, with Connie and the shotgun close behind and the rest of us tagging along after. Kinuno crouched down and stalked the guineas as if they were record-book kudu, dead serious. When they reached the bush he took Connie’s arm and pointed out the unsuspecting fowl, not fifteen paces away. “Piga,” he said and stuck his fingers in his ears. Connie raised the shotgun, closed her eyes, and pulled both triggers, blam! blam! Kinuno watched disconsolately as the startled flock thundered into the air, leaving no victims behind, and then turned around with a shocked expression as the rest of us started laughing. But when he saw that even Len was doubled up with glee, a broad grin slowly split his stolid, honest face.

Connie and Len with Thomson gazelle.

We packed up the camp and moved most of the way across Kenya, to Block 21A on the Galana River, in the hot, low, semi-arid brush country between Tsavo Park and the coast. We spent a night in Nairobi on the way, and Berit collected young Erik, who perforce had to come with us. So we rolled down the Mombasa road en route to elephant country with a baby’s crib lashed to the roof of the hunting car. We camped in a no-hunting sanctuary that ran a mile deep along the river, close to a game trail that led to a watering place. One evening a bunch of elephant that had come to drink stampeded. Perhaps they had suddenly caught our scent, or heard pots clattering in the kitchen. In their panic-stricken flight they knocked over a latrine tent, which luckily was unoccupied at the time. That was quite unusual, though; during the other times we had elephant in camp at night they did not disturb so much as a guy rope.

Len added a warthog to his collection, and an old lesser kudu with an inch or two worn off the tips of its horns. We found a herd of fringe-eared oryx, the big, hardy desert antelope with the javelinlike horns that Winston Churchill described as resembling a troop of lancers, up near the Kulalu Hills on the Tsavo border. Len took a very fine, heavy-horned 29½-inch bull out of the bunch, and was delighted. So were we and the camp staff, because, perhaps unexpectedly, oryx make very fine eating.

The Galana was not reckoned to be good buffalo country, because their horns tended to be small and ugly in this area. But one day we came across some bachelor bulls feeding along a brushy draw and were surprised to notice that one of them had a very fine, massive head, much better than Len’s first one. We got in front of them and let them come to us, and after a little excitement Len collected the big one.

But for the most part we hunted elephant. They crossed back and forth from Tsavo Park, and knew exactly where the boundary lay. If one bashed a bull anywhere near the boundary, it would by all means endeavor to get across it. If it succeeded, if it fell even one yard across the line, it became the property of the National Parks and the hunter had lost his trophy, but was nevertheless considered to have filled his license. But after looking over many jumbos and finding only cows, calves, and young bulls with mere “cigarettes” sticking out of their mouths, we at last chanced onto two bulls traveling together, and they were safely many miles from the boundary. One was obviously immature, but the other bore long, slender, evenly curved tusks. I told Len that they would not go over sixty pounds, but that given their length they would make a beautiful trophy. He replied, “Fine, let’s go get him.”

They were just loafing along, but even at that gait an elephant can cover an amazing amount of ground in short order, and we had to hustle to catch up with them, while taking advantage of the wind and a little cover as we got closer. Eventually Len had a clear heart/lung shot at perhaps sixty yards, but did not make enough allowance for the bull’s pace and got it a touch far back and a little low. As it turned away, I tried unsuccessfully for the spine above the root of the tail. Kinuno and I ran after it and pounded its rear end further, and at last it went down.

As we walked up to it, the elephant shrank; the closer we got to it the smaller it became, which is the opposite of the normal phenomenon. Usually, when an elephant is lying on its side one cannot see over its belly, but the top of the belly of this one came barely chest-high. The bloody thing was a dwarf! Instead of weighing sixty pounds a side, the tusks went barely forty pounds each, though they measured 6½ feet in length. What had fooled us, I believe, was that no other adult elephant had been with this one to give us a scale of its size. I was utterly horrified and deeply mortified, but Len made light of it. It was his elephant, he said, and he was happy with it. Besides, the small tusks would fit perfectly in their low-ceilinged apartment. Spoken like a gentleman and a scholar—and a true sportsman.

Leonard Burke with the first four-footed animal he had ever hunted.

We fetched the crew from the camp to chop out the ivory, remove the feet, and take the ears for leather. We left them a pickup and a rifle, and drove away to look at more of the country, identify some birds, chase the giraffe, take a few pictures, and savor the last day of the safari.

While they were busy at their work the crew was startled by a loud shriek, and looked up to see two cow elephant charging down on them, trumpeting and screaming in outrage. Mutunga climbed into the back of the pickup and burrowed under one of the elephant ears that was lying there, Kinuno grabbed the rifle and fired a shot in the air, while Kamonde started the vehicle and began to drive off. At that the cows swerved aside and went away, still crying murder, which from their point of view it was. I always hated killing elephant!

Len and Connie had become so enamored of Africa that they came back to hunt in different parts of it many times thereafter, while Connie took up the rifle and became a very experienced hunter herself. When Len five years later brought Ronnie Berman to hunt with me, the wheel had turned almost full circle. Len had all the African trophies he wanted, save one, and now found it more satisfying to watch his young protégé begin to experience it, and to fall in love with it all, rather than to try to do it all over again himself. Len fired only one shot on the whole trip, to collect the gerenuk he had regretted not buying a license for on that first, wonderful, memorable, happy safari.