HOMECOMING

CHAPTER 17

Early in May of 1977 I went down to a hunting block between Athi River and Konza, not thirty miles from our home on the outskirts of Nairobi, seeking meat for the nearly empty freezer. The long rains, bounteous that year, had recently broken a protracted drought, and the Athi plains were green, fresh, and studded with wildflowers. When I signed in at the game department post at Athi River the game scouts asked me to shoot a Grant gazelle for them. I protested that I did not have a license for a Grant, but they said that it did not matter, that it would not count.

Not far into the block I spotted a herd of thirty or forty wildebeest (gnu). They are odd-looking animals with buffalolike horns, white beards, horselike manes, gray, sloping bodies brindled with darker stripes, and long, flowing tails (which make excellent fly whisks.) Nevertheless they are true antelope related to the hartebeest. They are quite crazy, liable to gallop off in all directions for no discernible reason at all, and then to wheel around and come back or to suddenly stop and calmly start grazing as if nothing had happened. In this respect they remind me somewhat of caribou. They are also much the same size, and their meat is excellent.

There was little cover, but finally, by making use of shallow folds in the terrain, I managed to get ahead of them and let them move slowly past me at a range of about two hundred yards. I sat down with the 7x64mm Mauser and waited until a dry cow appeared to be in the clear on the fringe of the bunch. But at the shot it ran, while another, which must have been exactly in line beyond it, staggered and went down. It was still kicking, so I gave it a finisher, and then found the first one dead a little distance away. The 173-grain RWS H-mantel (partition-type) bullet had penetrated through the first gnu close behind the front legs (which was a little farther back than I had meant to place the shot), and had then struck the second in almost exactly the same spot. I had several times got two impala with one shot, but this was the first time I’d experienced it with wildebeest. It was quite unintentional, but it did not matter as I had tags for two wildebeest and had meant to fill them in any case.

I spent a couple of hours skinning and cutting up the wildebeest and loading them into the Toyota, and then went after a Granti for the game scouts. I found some on absolutely flat ground where there was no possibility of making a stalk, so I just walked openly and casually obliquely toward them, until at last they had let me close to within about a hundred fifty yards. I went to kneeling so as to be able to see over the tall grass, and dropped one of the gazelle in its tracks. It was the last shot I ever fired in Africa.

Two weeks later we were visiting some friends at Karatina (not far from Mount Kenya), planning a hunt on which Berit would try for a buffalo, when our host came in and put the newspaper down on the breakfast table in front of us.

“HUNTING BANNED” proclaimed the headline. “Directive to Save Wildlife. All game hunting has been banned in Kenya. All hunting licenses have been cancelled, and all hunting safaris have been told to stop—at once. Announcing the ban yesterday, Tourism and Wildlife Minister Mr. Mathew Oguto said: ‘There are no exceptions . . . the ban is indefinite.’ Mr. Oguto said the Firearms Bureau had been told to cancel all licenses for hunting weapons immediately. . . . Mr. Oguto said the government would lose ten million shillings a year from lost hunting license revenues. He assured that hunters whose licenses were cancelled would get their money back.” (I am still waiting for it.)

Kenya’s populations of elephant, rhino, leopard, and to some extent zebra were being decimated by poachers, there was no question about that. For years the price of ivory had held steady at one pound sterling (approximately $2.50) per pound, and license fees were set accordingly, so that the ivory from a fifty-pounder would just about cover the costs. There was a little poaching, mainly by tribesmen using bows and poisoned arrows, but it was no problem. The chief threats came from Kenya’s explosive population growth; settlement and cultivation were rapidly encroaching on the elephant’s remaining habitat, and many hundreds had to be shot by the game department in defense of crops every year, while in Tsavo National Park thousands died of starvation.

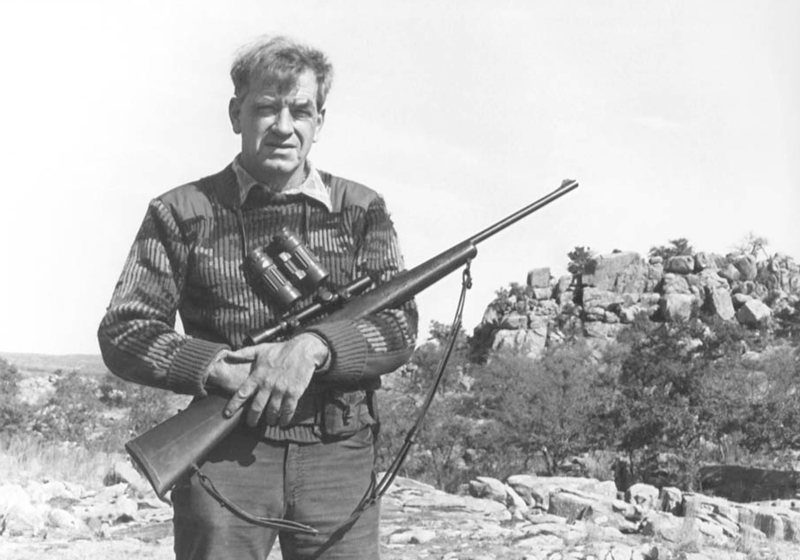

Finn, holding one of the many guns he tested, in the rocks of the Bar-O Ranch.

In the early 1970s the price of ivory on the international market started to rise; it doubled and quadrupled and still went up (it stood at $100 per pound in 1990), and then the dam burst. Bushmen with their primitive bows were replaced by organized gangs of poachers (many of them from Somalia) armed with modern rifles, including fully automatic AK-47s, who wiped out whole families of elephant at a time and swept the country clean of rhino, and who had sufficient determination and firepower to overawe the underpaid game department and national park scouts armed with obsolete Mark III .303 Lee-Enfields.

To compound the mess, several powerful members of the ruling hierarchy were most profitably involved in the buying and exporting of poached ivory, and could not be touched. The Nairobi police stopped and impounded a truck full of undocumented ivory, and threw the driver in the pokey. Within the hour an order came down from on high: Turn the driver loose, give him back the truck and the ivory, delete all mention of the incident from the records, and let him go on his way.

The government had lost control of the situation, so in order to quell the rising tide of criticism, both at home and from abroad, they banned legal, licensed hunting, an activity that gainfully employed several thousand Kenyans and brought in better than six million dollars in desperately needed foreign exchange every year while taking only 6,000 animals of all species a season. (In comparison, three times as many whitetails are harvested yearly in the county in which I now live.) As a result, elephant numbers, which stood at over 65,000 for Kenya at the time of the hunting ban, have been reduced to a mere 17,000 twelve years later, and are still steadily declining. (Such is the logic of governments—when faced with a violent, drug-related increase in crime in this country, the response is an attempt to disarm the law-abiding citizens! This makes about as much sense as the Kenya hunting ban, and would prove equally effective.)

Interestingly enough, Kenya’s parliament was not consulted before the ban on hunting was proclaimed, and no free debate on the issue was ever permitted. Under the British colonial regime, the law had been written with the convenience of the bureaucracy very much in mind. The chief game warden was given the power to revoke anyone’s game license at any time, without having to give any explanation or justification. This worked well enough so long as the incumbent was a product of the old English public school system with a deeply ingrained sense of fair play, but it was obviously open to abuse. Be that as it may, the Kenya government was able to impose the hunting ban immediately, and without any public discussion, by simply having the chief game warden revoke all hunting licenses. The lesson should be obvious.

After reading the newspaper article, I got up and walked out onto the veranda in a slight state of shock. We would have to cancel the safaris we had booked, and return the deposits. We might fill in to some extent with photographic safaris, although they bored me, and we could extend our farming enterprise. Even now Berit was doing quite well from our five-acre plot. She sold the milk from our two jersey cows, eggs from three hundred hens, and vegetables from the garden to the embassies and expatriate communities in Nairobi, and was supplying ducks to one popular restaurant. If we obtained a little more land we might make something out of that. On the other hand, did I really want to stay in the sort of country Kenya was becoming, and in a place where I could not occasionally go out and hunt for myself? More to the point, could I consent to being disarmed, and to having to live in Africa with no effective means of protecting myself and my family?

I turned to Berit and said, “That’s it. We are leaving.”

I wrote to everyone I knew in the United States, most of them former clients. Ever since my schooldays I had admired and been convinced of the truth of the ideals on which America was founded, and was, as I still am, a fervent supporter of the Constitution and Bill of Rights. Dunlop Farren in Houston (who with his wife, Sue, had hunted with me the previous year) proved to be a true friend when we needed one, and what we owe him we can never adequately repay. He found me a job with an exotic game operation near Kerrville that would qualify us to enter the country as permanent residents, and then spent untold hours shepherding the application through all the byways and detours of the bureaucratic process. In the end we landed in Houston in the fall of 1978, a year and a half after the hunting ban was imposed.

The exotic game hunting concern was a put-and-take, guaranteed-kill type of operation, and not exactly my style. But while working there, I was sent a couple of times to guide hunters on a seven-thousand-acre ranch near Llano in the Hill Country of Texas, where the exotics were not fenced in or fed but were completely free-ranging and lived as naturally as the numerous native white-tailed deer. I suggested to my boss that in addition to the guaranteed-kill type of hunting, we should offer fair-chase hunts on foot on this property, but he could not see it. When I asked him if he would mind if I pursued the matter on my own account, he replied that would be fine.

The upshot was that I made arrangements with Dr. Buttery, the owner, to live in the huge old ranch house (which has a hallway twenty-five yards long and sufficient room to put up all the clients I could handle at one time) and take over the exotic hunting on his Bar-O Ranch. The property had previously belonged to the Moss family, whose ancestors had been granted land in the area for service in the Texas revolution. Mark A. Moss had started to stock exotic game on it around the time of World War II. Exactly when the various species were introduced I could not determine, but the aoudad (Barbary sheep) were established by 1945; Herb Klein, writing in Mellon’s African Hunter, recorded killing one on this ranch while hunting mouflon here in that year. I also received permission to hunt exotics on the neighboring Inks Ranch (whose owner, Jim Inks, is a nephew of Mark A. Moss) and some others, including the Greenwood Valley Ranch near Rocksprings with its abundant axis deer.

Finn with Dunlop Farren, Kinuno, and fringed-ear oryx in Kenya. Dunlop spent countless hours helping us legally immigrate to the United States.

For nine years I guided hunters here for a living, allowing nothing but strictly fair-chase hunts wherein the game was stalked on foot. I started writing on the side, and then George Martin offered me a contract to write exclusively for the National Rifle Association, which I was proud to accept. In 1988 I closed down the guiding business so that I could write full time, but we continued to live in the old ranch house and keep an eye on the exotic game. In the meantime Berit went back to school, and qualified first as an LVN (licensed vocational nurse) and then, after two hard years of driving two hours each way to classes, as a registered nurse.

Llano is a pretty little town of three thousand good folks lying on the Llano River seventy-five miles west of Austin, the closest city of any size. It is a solid town too, with a sense of community and pride in itself. The small hospital is excellent, and so are the schools, where discipline is still administered with a paddle when that is necessary. The marching band does outstandingly well in state competitions, and even the football team won more games than it lost last season. It has been a wholesome environment in which to raise kids.

The country looks a great deal like some parts of Kenya. It is mainly open oak and mesquite woodland, with occasional stands of elm and hickory, and big pecan trees along the watercourses. In places the sweet-smelling bee brush grows thickly, and prickly pear is widespread. Mustang grapes, which make delicious jelly, grow wild. The terrain is hilly, with fantastic granite outcrops and rocky ridges, and there is little arable land. This is ranching country: cattle, angora goats, and some sheep. And turkeys, and white-tailed deer—more whitetails per square mile than almost anywhere else on earth.

The deer are small, but exceedingly abundant. I have come to love them, and would not again very willingly live where I did not have them around me. Most of the deer hunting on the ranch is leased out on a permanent basis. Some of the hunters have been coming every season for the past thirty years and more, and now their grandchildren hunt here as well. A few of the lesser, but still amply spacious, pastures are not leased out, and there we are permitted to collect our venison. We hunt whitetails in season by simply picking up a rifle and walking out from the house far enough to avoid killing the house deer, and then we still-hunt.

My shooting bench is by the creek, not a hundred yards from the house, which makes load development in particular very convenient. It is shaded by a huge, ancient live-oak tree and a big pecan tree that yields quantities of excellent nuts, most of which the squirrels get, just as they get all the fruit from the pear tree outside the kitchen window.

We share this ramshackle, near-century-old house with many different creatures. The armadillos root in its lawn and flower beds, and bang and rattle against the hodgepodge of plumbing under its floor when they come in at night. Squirrels scamper about the attic, and grow fat sprawled out on the bird table, where they are just as entertaining as the birds. A courageous and busy little wren raised her young on a shelf in Marit’s room, between two Cabbage Patch dolls, and a phoebe insists on building her nest every year around the light that hangs on the porch outside the front door. Hummingbirds buzz and strafe each other at the feeders all summer long, while at least a dozen glowing cardinals brighten the yard. The mud-dauber wasps litter the porch with paralyzed black-widow spiders, and cause me to plug with bullets the muzzles of the guns we keep openly displayed in a rack. A colony of harvester ants lives by the corner of the porch. They cut the leaves from the pear tree unless I sprinkle Sevin dust around it, and all day a stream of them march home with cracked corn and seeds from the bird table. Two tremulous cottontails nervously nibble at the grain the careless squirrels spill, and at night a plump raccoon comes to clean up whatever the ants, the birds, the rabbits, and the squirrels have left. There is no provision for locking the doors of the house, nor is there any need to do so.

Nearly every evening I go for a brisk, one-hour walk, and if she is home Berit accompanies me. Often I’ll take a pistol along and fire a magazine or cylinder full at cactus pads where there is a safe backstop, to help keep my eye in—it needs all the help it can get. We always see some wildlife: aoudad, feral hogs, and axis, sika, or fallow deer; and I cannot remember the last time we failed to put up a whitetail; usually we see at least a dozen of them. Our way of life is essentially the same as it was on the Yatta and at Juja Farm. I do not know of a better place in the world to live, and I believe that at long last I have come home.