A Good Man Is Hard to Find

A Good Man Is Hard to Find

by Jeff Cooper

A Good Man Is Hard to Find

A Good Man Is Hard to Find

If one keeps up with news, he is inclined to give up on the human race now and again as a rather sorry reflection upon God’s efforts—but not always. Once in a while an honest-to-God man turns up, and such a one was the late Finn Aagaard, whom it was my great good fortune to know as a friend and colleague.

Finn was Norse by extraction, but spent most of his life in Kenya up until the time that once-lovely place was “given back to the Indians.” Finn was a hunter by trade, and naturally could not remain in a country where hunting became prohibited. He moved with his family to Texas, where it was that I met him. Finn had been a professional hunter in Africa, but that is not much of a trade at this time in Texas, so we in this country know him primarily as a “gunwriter,” a term we both could do well without. As an author he was handicapped by his absolute and uncompromising honesty, which made his work sometimes a tad difficult to sell. He was also characterized by charming modesty, which is also rare in specialty journalism. (“Aagaard,” incidentally, is pronounced exactly like the handheld boring tool. I have this, incidentally, on the authority of Berit, Finn’s wife, who is also of Norse extraction.)

It is a pleasant experience for a specialist to encounter a colleague with whom he agrees completely on the more arcane aspects of their mutual specialty. This is particularly true when these opinions have been arrived at independently without personal conference. I do not mean to suggest that I admire Finn’s work because he agrees with me, but I could not help taking pleasure in discovering that he and I arrived at similar attitudes about hunting and firearms before we had ever met, especially since those attitudes are not generally held. As examples, we both fancy medium-weight, medium-bore rifle cartridges that impact at medium velocities. We share a strong aversion for the “tape-measure hunters” who value the size of the trophy more than the experience of the hunt. We regarded each other as carnivorous predators, more in tune with the meat-eaters than the grass-eaters. We love the wonderful creatures of the wild, which we hunt, but as hunters we seek the prey animals more than the predators. Finn once told me he had never pressed the trigger on a leopard, and did not intend to, which I thought was my own private viewpoint. I regard the leopard as too beautiful to shoot. Finn regarded him additionally as a comrade-in-arms. Neither of us decries sport hunting of game animals when conducted in a sporting fashion, but neither of us considers the trophy to be an end in itself.

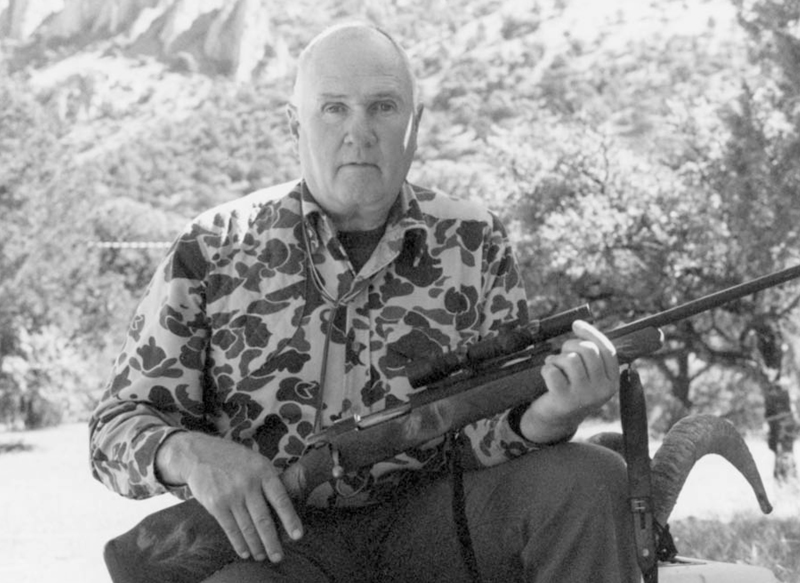

Jeff Cooper. (Photo courtesy of Lindy Wisdom)

Finn told me once that he regarded the elephant as the greatest of game animals, but one that, paradoxically, was an embarrassment to kill. The elephant is too majestic, too wise, and too aware to serve properly as a target. I do not know how many elephant Finn took during his career in Kenya, but he never liked to stay around to supervise the dressing out of the fallen beast. He did not object to elephant hunting, but while he enjoyed the hunting, he invariably regretted the killing. I have been in on the death of only three elephant, but I felt exactly the same way, and this was before I even met Finn.

Finn was an excellent shot. I can say that without qualification since I have spent much of my adult life as a professional marksman. He had no trace of the know-it-all attitude so common among outdoor writers; he never suggested that he knew all he needed to know about shooting but on the contrary sought every chance to learn anything that he had not encountered before. We disagreed slightly on matters of recoil effect, but that is probably because his acquaintance with the recoil-shy derived more from the client than from the student. We were, of course, absolutely committed to the notion that proper bullet placement, rather than velocity or energy, is what produces immediate, humane kills. I am pleased to say that he was with me when I took down a prime bison almost instantaneously with one shot.

I conducted rifle classes on two occasions when Finn was a student, and while I expected him to be a fine marksman, I was especially gratified by his performance under pressure. It is not necessary to point out that nervous tension is greater under controlled conditions on the range than it is with quick response in the field.

I hunted bison and nilgai with Finn in Texas, and will say that his extensive experience in the field was evident. He was definitely the right man to have beside you, rifle in hand. Moreover, this applies more to gun handling than to marksmanship. If a sportsman is going to be exposed to deadly peril in the hunting field, it will certainly come more from rifle fire than from fang or horn.

The traditional hunter has always been primarily a naturalist who not only admires his prey but also loves it deeply. This personality trait seems to baffle the nonhunter, but then there are a great many things the nonhunter does not understand.

Finn acquired an excellent library during his professional career, and we exchanged volumes on various occasions. He retained what he read, and developed a greater degree of critical analysis than is often evident in professional hunters. A great deal has been written about big-game hunting, both in Africa and elsewhere, and a good bit of it is utter balderdash. Finn understood the difference between the authoritative and the foolish, and this gave rise to several bull sessions, the memory of which I treasure.

In seeking to profit by the experience of the masters, we always get around to discussions of the relative danger involved in the hunting of dangerous game. As mentioned, the greatest source of peril on a dangerous-game hunt is the rifle of your companion, but to go beyond that, hunters always like to exchange views about the relative deadliness of various sorts of quarry. Today it is commonplace to discuss those beasts termed the “Big Five.” This is a fairly recent development, and I think it may be mistaken. When both Finn and I were starting out, the dangerous animals were known as the “Big Four”—elephant, buffalo, rhino, and lion. The leopard was not included, simply because the animal is too small. Certainly he is scratchy and he is dauntingly fast, but in Africa he rarely kills a hunter. In exploring this question among sportsmen of wide experience, I ran across the popular view that the leopard actually hunts people in India but not in Africa, apparently because the cats are very fond of curry. (Well, so am I and so was Finn Aagaard.) More to the point of the animals’ relative danger, most of the old-timers gave the elephant first place, as did Finn Aagaard. This is because the elephant is simply brighter than other members of the dangerous clan. Above all, the elephant is aware, and Finn treats this matter very seriously. The elephant knows what is going on and knows when he is being pursued. He also has more of a capacity to determine what to do about it. In numbers of hunters killed, buffalo may outrank the elephant, but this is because the buffalo is hunted largely for meat, and in large numbers, thus making for more contacts between hunter and hunted.

There are those who place lion first among the dangerous adversaries, but Finn was not one. He respected the lion, but one had never caught him, and that doubtless affected his opinion.

The rhino has indeed killed a number of people, including the renowned American professional Charlie Cottar. But most people, including Finn, hold that the rhino is simply too stupid to rank up there with the leaders.

As for hippo, Finn was well aware of the lethal record of the hippopotamus, but prized this beast more for his hide, his meat, and his fat than for his trophy. Hippo fat is the sovereign remedy for almost every physical problem among the Bantu, but the hippo is not a target of the sportsman, as are members of the Big Four. I think he should be, if hunted on dry land on his way to the river, and this is another impression that Finn and I shared.

Finn Aagaard naturally could not transfer his hunting life from Africa to Texas, though he did what he could to keep the range passion burning. The hunter instinct is elemental to the human psyche, despite what the grass-eaters among us would say. This is a study of its own, but Finn Aagaard was a hunter, and he knew he was a hunter, and he was proud of being a hunter. “Polypragmatoi” is a term we have coined to denote those people who insist upon minding other people’s business—the busybodies. Such people scamper about telling real men such as Finn Aagaard how they should conduct their lives. He found it annoying, ridiculous, and bothersome, as indeed they are. He felt, as many of us do, that man is at his best in the wilderness, and armed in the wilderness. Man’s relationship to his heritage and to his environment is based upon his command of the situation, which is the result of his intelligence, skill, courage, and hardihood. Finn has written some very good stuff about the relationship of man to the wild, and he was scornful of those who did not understand and those who would tell him how to mind his own business. As such, Finn Aagaard was a true champion of social and political liberty.

Having been exiled from what had become his home country, he settled in the United States of America, the last hope of earth. As with many “converts on the road to Damascus,” Finn prized the American spirit of liberty more than most native Americans can. Those who had the marvelous good fortune to be born here are often unaware of the unique blessings bequeathed to us by those saints of liberty who built this country. Finn became almost passionate about his devotion to the U.S. Constitution and its Bill of Rights. There are no rights today in Kenya, or for that matter Norway. Where does a man who understands the right to liberty flee today? Finn came here. He dug in his heels. He locked his piece. He preached. He voted. Anyone looking for a role model needs look no farther.