11

MONUMENTS IN STONE

One of the most durable forms of evidence of Viking Age England are the Anglo-Scandinavian stone monuments which can be found in many churches and churchyards, especially in Derbyshire, Lincolnshire, Yorkshire, Lancashire and Cumbria. Yet whilst the animal ornament and iconography is in a Scandinavian style, the erection of stone crosses was not a Scandinavian tradition.

Viking Age sculpture represents a special blend of Scandinavian, Anglo-Saxon and Celtic traditions. Although rune-stone memorials were erected in several parts of Scandinavia, and Gotland is famous for its picture-stones, there were no stone carvings in Scandinavia until the end of the tenth century. In England, however, there was a flourishing Anglo-Saxon tradition of stone sculpture. Elaborately decorated architectural stonework and standing stone crosses are found at early monastic sites (Lang 1988). Many crosses may have been grave-markers but some appear to have been memorials to saints, or boundary markers. Stone sarcophagi and decorated recumbent stone slabs were also sometimes used to mark particularly wealthy graves.

Scandinavian settlers in the Danelaw embraced the Christian tradition of erecting stone memorials to the dead and developed it as their own. Anglo-Scandinavian crosses are particularly prevalent at sites where there was already Anglo-Saxon sculpture, suggesting less disruption to ecclesiastical sites than is often assumed. At the monastery church at Lastingham (North Yorkshire), the crypt contains sculpture decorated in both Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Scandinavian styles. It has been estimated that 60 per cent of Yorkshire sites with Anglo-Saxon sculpture also have Anglo-Scandinavian sculpture; in Cumbria, of 15 sites with Anglo-Saxon sculpture, 12 also have Anglo-Scandinavian crosses. The patrons may have changed but it appears the local masons still found employment. Some continuity is also apparent in the styles of ornament used. Although Anglo-Scandinavian sculpture borrows decorative styles and motifs that can be found throughout the Viking world, there are also Anglo-Saxon elements in the design. The vine scrolls at Middleton, Brompton and Leeds, for example, are clearly derived from those on the earlier Anglo-Saxon crosses at Ruthwell and Bewcastle. The organisation of decoration into distinct panels was also an Anglo-Saxon practice rather than a Scandinavian stylistic trait.

However, by the Viking Age, stone memorials are found at five times as many places as in the eighth and ninth centuries. In Cumbria there are 115 monuments of the tenth and eleventh centuries from 36 sites. In Yorkshire there are approximately 500 monuments at over 100 locations, about 80 per cent of which may be dated to the Viking Age. Some are concentrated at known religious centres but Anglo-Scandinavian sculpture has also been identified at numerous sites where there is no Anglo-Saxon work. These sites represent an expansion in the number of centres commissioning crosses from the tenth century onwards. This increase corresponds with the decline of monastic patronage, and the transfer of resources to a new secular aristocracy. These were prosperous landholders, particularly those farming the rich agricultural land of the Vales of York and Pickering. Christian crosses now came under secular influence as the new local elite employed them to signify their status and their allegiances.

Tenth-century sculpture in the Danelaw is therefore different from the sculpture that preceded it, not only in terms of ornamentation, but also in terms of location and function, since much more is clearly funerary. These monuments represent individual aristocratic burials. At most churches in Lincolnshire and Yorkshire there is sculpture from only one or two monuments, and David Stocker has suggested that many of these crosses were the founding monuments in a new generation of parochial graveyards. However, there are a number of churches with many more sculptures. These are frequently located in trading places, such as Marton-on-Trent, Bicker and St Mark’s and St Mary-le-Wigford, in what has been termed the ‘strand’ of Lincoln (Stocker 2000). These exceptional graveyards may belong to unusual settlements occupied primarily by mercantile elites.

In Ryedale, where most Anglo-Saxon churches contain Anglo-Scandinavian crosses, these include a distinct group of so-called warrior crosses, such as those at Levisham, Weston, Sockburn, and Middleton (North Yorkshire). The Middleton warrior was once thought to represent a pagan Viking warrior lying in his grave, but is now seen as an Anglo-Scandinavian lord seated on his gift-stool or throne and surrounded by his symbols of power (17). Regional patterns in ornamentation, form and iconography, as well as reflecting locations of schools of sculptural production, may also reflect regional power groups, in which lords signalled their allegiances and status through commissioning particular types of sculpture. A uniformity of style and ornament can be identified across the whole of eighth-century Anglo-Saxon Northumbria, maintained by a common monastic tradition and inter-monastic contact. This was broken down in the ninth and tenth centuries after the Viking immigration, with the development of identifiable local sculptural traditions and workshops (see chapter 7).

17 The Middleton Cross was extracted from the church fabric in 1948. It was once thought to represent a Viking warrior lying in his grave but is now generally interpreted as a warrior-lord sitting on his gift-stool or throne. The pellets above his shoulders are part of the chair. He is wearing a pointed helmet and carries a long knife, or scramasax, at his belt. He is surrounded by his symbols of power, including spear, sword, axe and shield.

In the coastal areas of north-west Cumbria, for example, there is a concentration of circle-headed crosses. The distribution is centred on the Viking colonies of the western seaboard between Anglesey and northern Cumbria and illustrates the importance of coastal links. An outlier at Gargrave (North Yorkshire) suggests that settlers in the upper river valleys may have originated from the west rather than the east.

In Yorkshire, the grave slabs excavated at York Minster served as a model for many Yorkshire stone monuments, although the motifs were borrowed and modified in Ryedale and other areas. In Ryedale, for instance, the crosses at Kirkbymoorside, Middleton and Levisham all share the same peculiar style of cross head, with a raised outer crest on a ring connecting the arms. The sculptors frequently combined new with old elements. In York the tenth-century sculptors promoted original Anglo-Scandinavian-style designs as well as maintaining continuity with Anglian traditions. Most of the Yorkshire crosses were probably carved not in the initial phase of Scandinavian settlement, but in the period 900-50, after the expulsion of the Norse from Dublin, during the period in which Yorkshire was under strong Hiberno-Norse influence (Lang 1978; 1991). After the expulsion of Erik Bloodaxe in 954, York metropolitan sculpture developed more under Mercian influence, while Ryedale sculpture became introverted and insular with little evidence for further external influence (Walsh 1994).

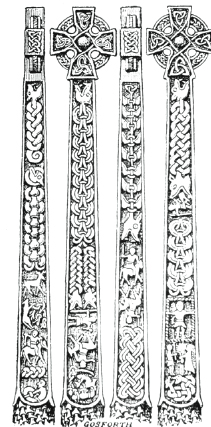

18 The Gosforth Cross, Cumbria (after Collingwood). The cross, which stands 4.2m (14ft) high, was cut from a single piece of red sandstone. Its pictures exploit the links and contrasts between Scandinavian and Christian theology. On one side there is a Crucifixion scene in which Mary Magdalene appears dressed as a Valkyrie, with a trailing dress and long pigtail. On the other sides scenes from Ragnarok are depicted, at the moment when the gods’ enemies, the forces of evil, break loose from their restraining bonds. The Fenris wolf is seen escaping from his bonds to attack Odin. The evil god Loki is seen chained beneath a venomous serpent whilst his wife catches poison in a cup. Heimdal, watchman of the gods, is also depicted with his spear and horn. In the ensuing battle monsters and gods perish as earthquake and fire sweep all away. From this chaos emerges a new cleansed world

In Lincolnshire the tenth-century sculpture also represents the remains of grave markers set up to commemorate the founding burials in a new generation of parish graveyards (Everson and Stocker 1999). This new burial fashion reaches Lincolnshire slightly later than Yorkshire; all the crosses were erected between 930-1030, and most can be dated 950-1000. These are again derived from Hiberno-Norse prototypes in Yorkshire, north-west England and the Isle of Man.

In the Peak District area of Derbyshire, Anglian origins of the sculptural tradition are again reflected in the use of round shafts to the crosses. The majority of the Derbyshire crosses have been dated between 910-50. They demonstrate an Anglo-Scandinavian domination of political landscape, but it has been suggested that the level of continuity of design also indicates an acceptance of the West Saxon overlord and his Church (Sidebottom 2000).

Outside the Danelaw there are fewer examples of Viking Age sculpture, although examples from St Oswald’s Priory (Gloucester), Ramsbury (Wiltshire) and Bibury (Gloucestershire) do indicate the spread of Scandinavian taste into southern England in the tenth and eleventh centuries. In Cornwall, Scandinavian motifs appear occasionally, such as at Sancreed, Temple Moor, Padstow and Cardynham, displaying links with the Irish Sea area. The Isle of Man has one of the greatest concentrations of Viking Age sculpture, with 48 crosses produced in a relatively short time span of c.930-1020.

ICONOGRAPHY

The iconography of the Scandinavian crosses illustrates the close links of the Irish Sea area in the Viking Age (Bailey 1980). The same motifs and stories are frequently depicted in the Isle of Man and Yorkshire. The ring chain ornament seen on Gautr’s cross on the Isle of Man, for example, is also found in Cumbria, Northumbria and North Wales. Other Manx motifs, such as a distinctive style of knotwork tendril, display links with Yorkshire, particularly Barwick-in-Elmet and Spofforth, and there are further similarities with crosses in Aberford, Collingham, Saxton, and Sinnington all suggesting a great deal of contact and movement between the Isle of Man and Yorkshire (Walsh 1994). The hart-and-hound motif is found on the Isle of Man and in Cumbria, Lancashire and Yorkshire. The bound devil depicted at Kirkby Stephen (Cumbria) has parallels in similar figures from Maughold on the Isle of Man. The legend of Sigurd is also a popular scene in both areas, suggesting a shared set of beliefs and traditions.

Although most monuments are purely Christian, with the Crucifixion being the most popular scene, Christian, pagan and secular subjects are all depicted. In many cases Christian and pagan stories are combined by the sculptor, giving a Christian twist to a pagan tradition. One of the most startling examples is the Gosforth Cross (18) which has the Crucifixion depicted on one side whilst scenes from Ragnorok are shown on the others. The popularity of Sigurd on many crosses stems from his use to honour the dead, but Sigurd’s struggle with the dragon Fafnir also provides a link with heroic Christian themes. On a grave slab from York Minster (plate 22) Sigurd is depicted poised to stab the dragon. A panel from the cross at Nunburnholme (East Yorkshire) in which Sigurd has been recarved over a Eucharistic scene may be drawing attention to the Sigurd feast as a pagan version of the Eucharist. The heroic figure Weland, the flying smith, is another popular theme with subtle ambiguities. At Leeds (West Yorkshire) he is related to angels, and the eagle of St John.

Burial customs indicate that Scandinavian settlers apparently assimilated Christian ideas quite rapidly (chapter 10). Scandinavian paganism embraced a broad pantheon of gods, each of which had particular characteristics and might be called upon for specific functions; perhaps the Christian God was one more to be adopted into the fold. At Gosforth pagan and Christian images may have been seen as equivalent by the craftsman, rather than as the triumph of the new over the old; perhaps they were even regarded as aspects of the same theme.

HOGBACKS

A particularly distinctive form of Viking Age funerary monument is the so-called hogback tomb, named after its arched form. Hogbacks are recumbent stone monuments, generally about 1.5m in length. They are basically the shape of a bow-sided building with a ridged roof and curved side walls and are often decorated with architectural features such as shingle roofs, and stylised wattle walls. Over 50 hogbacks are also decorated with end-beasts (plate 23). These are generally bear-like creatures, although wolves or dogs are also known; sometimes they are shown with two legs, sometimes with four; many are clearly muzzled.

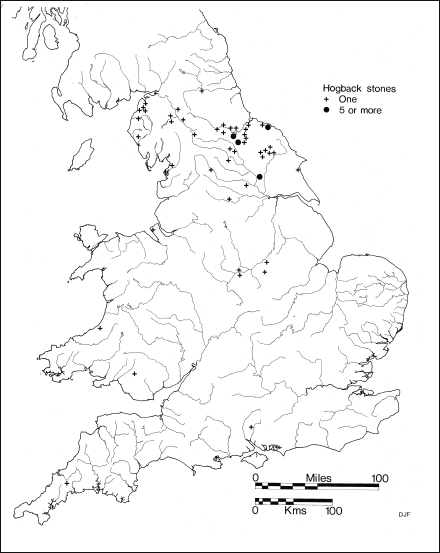

The distribution of hogbacks is mainly restricted to northern England and central Scotland, with a few outliers (19). They are concentrated especially in North Yorkshire and Cumbria, with none in the Isle of Man, and only single examples in Wales and Ireland. There are no hogbacks in the Danelaw areas of Lincolnshire and East Anglia and their distribution appears to be restricted to those areas which also have Hiberno-Norse and Norse place-names. Thus hogbacks appear to have developed in those areas which were subject to Hiberno-Norse influence, although they clearly spread east of the Pennines. Their absence from the Isle of Man may be explained simply as a function of the local geology, as the Manx slate would be difficult to cut into substantial three-dimensional forms, being more appropriate to flat slabs. Three Cornish hogbacks from Lanivet, St Tudy and St Buryan demonstrate the long-distance contacts of the Norse. This coastal distribution pattern is also seen around Scotland, emphasizing the coastal nature of much of Norse settlement.

19 Map of hogback tombstones (after Lang 1984)

It is likely that hogbacks are a tenth-century phenomenon; it has been suggested that most were carved within the period 920-70 (Lang 1984). Like most of the Anglo-Scandinavian sculpture in England, therefore, they belong not to the initial phase of Scandinavian colonisation in the ninth century, but to a second wave of Hiberno-Norse immigrants. Their origin has been much debated as they have no clear ancestors, either in Britain or Scandinavia. The best parallels are house-shaped shrines. In Anglo-Saxon England, stone shrines were used to contain or cover the body of a saint, although no ‘shrine-tombs’ are known from the area of hogbacks. Recumbent grave slabs were used to mark important burials and the Viking Age grave slabs excavated from under York Minster have central ridges. Perhaps hogbacks should be seen as three-dimensional extensions of this idea. Certainly they combine a number of cultural elements, including Trelleborg style bow-sided halls, Anglo-Saxon shrines and animal ornament. Some may have formed part of composite monuments with cross shafts at the ends, in the same way that some of the York Minster grave-slabs have end-stones. The so-called Giant’s Grave at Penrith combines a hogback stone with cross shafts in this fashion, although the possibility remains that this is a later rearrangement of the stones. The end-beasts may have originated as animals carved on separate end-stones which have subsequently been combined in a single three-dimensional monument. David Stocker has suggested that the significance of the muzzled bear may have been as the Christian symbol of a mother bear licking her cubs and bringing them to life (Stocker 2000).

Most hogbacks are no longer in their original location and so there are few cases where they can be associated with burials, although in the excavations under York Minster two hogback stones were found over burials. It has also been suggested that the spearhead found in Heysham churchyard may have come from the hogback burial (chapter 10). To the east of the Old Minster, Winchester, there was a group of four graves with limestone covers. One of these, grave 119, was covered with a hogback stone. This was the burial of a man of about 23, buried in a wooden coffin, his head resting on a pillow of flint and limestone; a Roman coin had been placed in the coffin. The hogback carried an Old English inscription along its back: ‘Here lies Gunni, Eorl’s [or the earl’s] fellow’. Subsequently, an inscription in Danish runes has been discovered on a fragment of stone found built into St Maurices’s church tower. Both are likely to have been early eleventh-century memorials, possibly commemorating followers of Knutr (Kjølbye-Biddle and Page 1975).

RUNES

The use of runic inscriptions is uncommon in England but is a feature of the Viking Age sculpture of the Isle of Man (Page 1987; 1999). Runic alphabets were developed by various Germanic and Scandinavian peoples in northern Europe in the first millennium ad. They continued in use into the medieval period but always seem to have been reserved for particular functions, such as formal inscriptions. In England a few Anglo-Saxon crosses, such as those at Collingham (West Yorkshire) and Hackness (North Yorkshire), were inscribed with Old English runes.

Some runes appear to have been endowed with magical properties, and weapons may have been inscribed to give them special powers. The runic script is particularly well suited, however, to being inscribed on wood and stone, the characters being formed of combinations of diagonal and vertical strokes. In some areas of Viking Age Scandinavia it became common practice to erect commemorative rune stones to honour the dead. They sometimes mark the grave but frequently they commemorate the death of someone far from home. Often they were erected at the roadside or at bridging points or meeting places. In Norway today there are some 40 rune stones; in Denmark less than 200; and in Sweden some 3500. The practice was not, however, generally followed in Scandinavian settlements overseas. There are no rune stones from Normandy, none in Iceland, two from the Faroes, and only a handful from Ireland. About half a dozen have been found in Scotland, with similar numbers from Orkney and Shetland.

In Britain the tradition was only developed on the Isle of Man, where the largest collection of runes in the British Isles is to be found inscribed on the stone crosses. The Scandinavians who settled in England did not generally maintain this custom and Viking runic finds are rare. Apart from the Winchester rune stone (above) the only other runic memorial in England was discovered in 1852 during excavation for a warehouse on the south side of St Paul’s Cathedral (plate 36). It is likely that this eleventh-century stone was in its original position marking a grave, as the remains of a skeleton were found immediately to the north of the slab. Along one edge of the stone was the inscription ‘Ginna and Toki had this stone set up’, probably to commemorate a Danish or Swedish follower of Knutr. Ginna may have been his widow and Toki his son; the name of the dead man was perhaps on another slab, never found.

The only other Danish runes from England are casual graffiti: inscriptions on animal bones from eleventh-century butcher’s waste from St Albans, and a comb case from Lincoln. On the other hand, Norse runes continued in use for some time in the north of England. There are runic graffiti from Carlisle Cathedral, Dearham (Cumbria) and Settle (North Yorkshire), and late eleventh and twelfth-century inscriptions on a sundial from Skelton-in-Cleveland, and on a font from Bridekirk (Cumbria). An inscription from Pennington (Cumbria) records the builder and mason of the church in bastardised Norse.

ANGLO-SCANDINAVIAN IDENTITIES

In summary, Viking Age stone sculpture represents the invention of new cultural traditions which developed at the interface between Anglo-Saxon, Celtic and Scandinavian peoples. These memorials symbolised identity and power, combining Christian traditions with the needs of the secular aristocracy. In Anglo-Saxon England, monasteries were centres of power and wealth, and the standing crosses would have been recognised as symbols of authority. It was natural, therefore, for the new local elites who came to power as a result of Viking incursions to seek to express their own power through the erection of stone monuments in Scandinavian art styles. Those patrons who commissioned crosses, such as that at Gosforth, supported craftsmen who drew extensively upon local traditions, but added motifs from pagan iconography. It should not be surprising that those areas where former large estates were being broken up into smaller land units under private ownership often coincide with a high density of sculpture. It was in these places where there were new claims to land which required representation in solid stone monuments which invoked the power of the Church, as well as the sword.

Viking Age England was a melting pot of cultural traditions. In all aspects of society, from settlement patterns to industrial production, it has been shown that for over 250 years England was subject to rapid and far-reaching changes. One of the questions posed at the start of this book was to ask how far the Vikings were responsible for this. In many aspects of life they had a catalytic role, but it is rather simplistic just to speak of Anglo-Saxons and Vikings. Over the course of the Viking Age new identities were being forged, and language and customs were each used to define and articulate an Anglo-Scandinavian identity. Whether it was through new place-names and new words, new forms of burial, new building types, or simply new dress fashion accessories, the peoples of Viking Age England were constantly re-inventing themselves. This process continues to the present day where, as the inhabitants of England continue to redefine their relationship with each other and with the peoples of continental Europe and Scandinavia, it is as relevant as ever.