Chapter 2: Switzerland in Depth

Switzerland has a rich cultural life, with many fine museums, theaters, and world-renowned orchestras, but most people visit the country for its superb scenery—alpine peaks, mountain lakes, and lofty pastures. As important as Geneva, Zurich, St. Moritz, and other obvious tourist centers are, they do not convey the full splendors of Switzerland. To experience these, you must venture deep into William Tell country, into the heart of Switzerland.

The Federal Republic of Switzerland covers 41,287 sq. km (15,941 sq. miles). It has four recognized national languages—German, French, Italian, and Romansh, a romance dialect. Many of its people, however, speak English, especially in the major tourist regions. You will find the Swiss hospitable, restrained, and peace loving. Switzerland’s neutrality allowed it to avoid the wars that devastated its neighbors twice in the past century. It also enabled it to achieve financial stability and prosperity.

Switzerland occupies a position on the “rooftop” of the continent of Europe, with the drainage of its mammoth alpine glaciers serving as the source of such powerful rivers as the Rhine and the Rhône. The appellation “crossroads of Europe” is fitting; from the time when the Romans crossed the Alps and traversed Helvetia (the ancient name for part of today’s Switzerland) on their way to conquests in the north, the major route connecting northern and southern Europe has been through Switzerland. The country’s ancient roads and paths were eventually developed into modern highways and railroad lines.

The main European route for east-west travel also passes through Switzerland, between Lake Constance and Geneva, and intercontinental airports connect the country with cities all over the world. London and Paris, for instance, are less than 2 hours away by air. The first modern tourists, the British, began to arrive “on holiday” in the 19th century, and other Europeans, as well as a scattering of North Americans, followed suit. The tradition of welcoming visitors is firmly entrenched in Swiss life, and the entire country is known for its efficiency and its cleanliness.

Did You Know?

• Nearly 6% of the working population of Switzerland is employed in the banking industry.

• As a financial center, Switzerland ranks in importance behind only New York, London, and Tokyo.

• Since the late 18th century, there has been no foreign invasion of Swiss territory, despite the devastating conflagrations that surrounded it.

• Until the early 19th century, Switzerland was the most industrialized country in Europe.

• Famous for its neutrality, Switzerland once was equally known for providing mercenaries to fight in foreign armies. (The practice was ended by the constitution of 1874, with the exception of the Vatican’s Swiss papal guard, dating from 1505.)

• Switzerland drafts all able-bodied male citizens between the ages of 20 and 50 (55 for officers). These soldiers, who continue to live at home, form a reserve defense corps that (in theory) can be called to active duty at any time.

• With its four major language groups, Switzerland effectively contradicts the axiom that a national identity cannot exist without a common language.

Don’t be misled. A visit to Switzerland is not tantamount to a visit to paradise. Even in the well-ordered and immaculate city of Zurich, there are drug addicts and the homeless wander its streets, although not in the vast numbers found in most of the world’s capitals.

Readers often comment on the reserve of the Swiss. The locals don’t necessarily rush to embrace you, as they are, for the most part, a conservative people. Even if they don’t have the spontaneity more associated with their southern neighbor, Italy, they will most often welcome you politely and provide you with a good bed and a good meal for the night—for which they’ll charge a good price! Few people return from Switzerland commenting on how cheap it is. However, good value is to be found by those who seek it out, and the Swiss probably have fewer “tourist traps” than most of the top 10 major tourist destinations of the world.

Switzerland Today

Don’t be fooled by Switzerland’s cookie-cutter folklore, its photogenic villages, and an image that its tourist officials widely promote—that of a well-oiled machine ticking efficiently from within the safety of an alpine landscape. The changes that the country has experienced lately have been as painful as anything since World War II, and have shattered long-cherished myths that were zealously taught to Swiss schoolchildren for years.

Ever since Switzerland horded millions of dollars in Nazi gold, it has been known as a bastion of banks secretly luring wealthy evaders, actually tax cheats, who wanted to stash away their gold beyond the reach of tax authorities in their individual countries, including Britain and the United States.

But a deal struck in 2009 between the United States and Switzerland changed all that. Very reluctantly, Switzerland has agreed to provide the names attached to nearly 5,000 secret accounts held by Americans at the Swiss bank giant UBS.

As the ensuing years have passed, Switzerland is gradually moving out of the tax refuge business. It was estimated that a third of the multi-trillion-dollar market in private wealth is controlled by Switzerland.

Don’t think the country willingly turned over its long-kept banking secrets. UBS was trapped by offering to help Americans hide their money, for which it was forced to pay $780 million in fines and restitution.

In all, the United States estimates that nearly $18 billion was—or is—held by Switzerland in tax-evading accounts.

The agreements are not perfect, and there have been threats and counter-threats on both sides. Each account holder can still appeal the decision to a Swiss court before the names are handed over to American authorities.

On other fronts, Switzerland was not only a great keeper of bank secrets, but also a bastion of tolerance. However, that appears to be changing in the face of the widespread Islamic immigration. In 2009, tensions reached the point whereby a referendum drawn up by the far right, although opposed by the government, passed with a clear majority of 57.5 percent of the voters.

Since the ban gained a majority in the cantons, it is now being added as a bylaw to the Swiss Constitution, which guarantees freedom of religion. The construction of minarets or mosques has drawn the greatest fire from the far right.

The justice minister of Switzerland, Eveline Widmer-Schumpf, claimed that the referendum “reflects fear among the population of Islamic fundamentalist tendencies.”

It is estimated that there are some 400,000 Arabs living in Switzerland, a country with a population of some 7.5 million people.

The cultural conflict is far from over. The message is clear to many immigrants coming into Switzerland. The welcome mat is not out.

On a more positive development, Swiss women for the first time captured most of the seats in the country’s seven-member executive branch of government in fall 2010. This move brushed aside Switzerland’s history as one of Europe’s last nations to grant women full suffrage. “We’ve reached the goal after a century-long struggle,” said Ruth Dreifuss, who in 1999 served as the country’s first female president. Swiss women did not gain the right to vote or to run in national elections until as late as 1971.

This emergence of female politicians still doesn’t set well with some Swiss men. Rene Kuhn organized an anti-feminism meeting in October 2010. He told the press, “We all know that when lots of women work together there can be more problems.”

Although this debate, and others, over the Swiss role in modern history is likely to continue long past the millennium, there is other trouble in paradise.

To the rest of the world, Switzerland is perceived as a very rich country—and it is. The magic economy has brought watch-making, chocolate-making, civil engineering, and tourism to high levels of accomplishments. But the high value of the cherished Swiss franc has cut deeply into the profitability of the country’s exports and into its tourism.

Many Swiss citizens don’t want to join the European Union, even though the country’s present nonmember status is severely affecting the Swiss economy. As the E.U. grows bigger, more and more markets become expensive for Swiss products, such as chocolate. An example occurred when Sweden, Austria, and Finland joined the E.U.; several Swiss exports were suddenly tagged with tariff barriers in those heretofore lucrative markets.

Trade protections from the E.U. aren’t the only things blocking Swiss exports. The cruelly high value of the Swiss franc continues to threaten exports as well. Swiss goods, even if they weren’t before, have suddenly become luxury items, and correspondingly expensive.

Even Swiss manufacturers are deserting their own country and going elsewhere where labor is cheaper and taxes are lower. For example, that Swiss chocolate bar you’re eating might have actually been made in Spain or Greece.

Though warned that failure to stay out of the European Union would mean trouble for their economy, Swiss voters in 1992 narrowly chose to remain outside the free-trade zone. As a result of that highly contested vote, the E.U. continues to impose the same trade barriers and protections against Switzerland that it does against Japan and the United States.

As an industrious people, the Swiss are taking steps to stay “lean and mean” with their manufacturing. For example, the august Swiss Parliament voted in 1995 to allow chocolate producers to use vegetable oils rather than cocoa butter in chocolate bars. In some parts of Switzerland, this provoked a massive outcry. Chocolate makers have slimmed down their workforces, becoming more mechanized and needing fewer workers who traditionally earn extremely high wages when stacked up against much of the Western world.

Discontented rumblings and differing opinions have been heard from various linguistic factions within Switzerland as well. The French-speaking section tends to be more cosmopolitan, more liberal, and more socialist than voters in the German-speaking hamlets of the country’s staunchly conservative center. (Residents of Italian-speaking Switzerland are, surprisingly enough, viewed as only a bit less conservative than their German-speaking compatriots, and in some cases, much less liberal than their French-speaking counterparts.) Interestingly, Zurich has been viewed as more fiscally stable and growth oriented than Geneva, reversing a trend. As for the European Union, Swiss women, young voters, and the country’s French-speaking western tier tend to favor membership, Zurich remains divided, and the German-speaking hamlets of the country’s center overwhelmingly are steadfastly opposed.

Switzerland remains one of the safest countries in the world to visit, but even its image of peace and tranquillity is being shattered by “tourist criminals.” Some of the most publicized of these have involved refugees from the traumatized Balkans and what used to be Yugoslavia. Many are people entering Switzerland with 3-month tourist visas who, with cameras, a bagful of Swiss handicrafts, and, in some cases, a guidebook in hand, have burglarized houses or mugged passersby in small towns that until recently had never experienced even a whiff of crime. Ironically, the vocabulary used by the Swiss to describe this unheard-of phenomenon often evokes lawless Chicago-style 1920s gangs from the era of Al Capone.

In spite of gnawing problems, there’s a lot to be proud of in Switzerland today. A proposal to increase the price of a university education in Switzerland was voted down by an assembly of town councils, a fact that makes a college degree for their children a distinct possibility for most Swiss families even today.

The country continues its impressive advances in technical training for high-skilled engineers and financiers, but artists still have a stony road to travel in their struggle to survive. Despite that, growing communities of counterculture photographers, painters, writers, and sculptors, as well as large numbers of gay people, continue to congregate in the inner cores of such cities as Zurich, Basel, and Geneva.

As mirrored in urban centers throughout the rest of Europe, victims of AIDS and other diseases, as well as heroin addicts, continue to find greater options in the country’s large cities than in small towns, and their migration from small towns toward Switzerland’s large cities continues. Although Switzerland is medically very advanced in the technology of providing substitutes (such as methadone) for heroin to deeply entrenched addicts, the use of such legalized, carefully controlled substitutes remains a hotly contested issue during virtually every election.

What most Swiss finally admit is that they’ve entered the real world whether they like it or not, and can never be viewed again as heirs to a nation of cuckoo clocks, contented cud-chewing cows, and Heidi’s great-uncle.

A Loose confederation of Cantons

Switzerland is a confederation of 3,029 communes, each largely responsible for its own public affairs, including school systems, taxation, road construction, water supply, and town planning. The international sign CH, found on Swiss motor vehicles, stands for Confoederatio Helvetica (Swiss Confederation). Over the centuries, neighboring communes have bonded together in a confederation of 23 cantons, each with its own constitution, laws, and government. They have surrendered only certain aspects of their authority to the Federal Parliament, such as foreign policy, national defense, and general economic policy.

The Federal Parliament of Switzerland consists of a 200-member National Council, elected by the people, and a 46-member Council of States, in which each canton has two representatives. The two chambers constitute Switzerland’s legislative authority. The executive body, the Federal Council, is composed of seven members, who make decisions jointly, although each councilor is responsible for a different department. The president of the Federal Council, who serves a 1-year term, leads the Confederation as primus inter pares (first among equals).

All Swiss citizens, in general, become eligible to vote on federal matters at the age of 20. Surprisingly, it wasn’t until 1971 that Swiss women were granted the right to vote.

Despite its neutrality, Switzerland has compulsory military service. The army, however, is devoted solely to the defense of the homeland. Swiss soldiers are always ready to fight—they keep military gear at home, including a gas mask, rifle, and ammunition. Annual shooting practice is mandatory.

Looking Back: Switzerland’s History

At the Crossroads of Europe

Despite its neutral image, Switzerland has a fascinating history of external and internal conflicts. Its strategic location at the crossroads of Europe made it an irresistible object to empires since Roman times. There’s even evidence that prehistoric tribes struggled to hold tiny settlements along the great Rhône and Rhine rivers.

The first identifiable occupants were the Celts, who entered the alpine regions from the west. The Helvetii, a Celtic tribe, inhabited a portion of the country that became known as Helvetia. The tribe was defeated by Julius Caesar when it tried to move into southern France in 58 B.C. The Romans conquered the resident tribes in 15 B.C., and peaceful colonization continued until A.D. 455 when the barbarians invaded, followed later by the Christians. Charlemagne (742–814) conquered the small states, or cantons, that occupied the area now known as Switzerland and incorporated them into his realm, which later became the Holy Roman Empire. In later years, Switzerland became a battleground for some of the major ruling families of Europe, especially the Houses of Savoy, the Habsburgs, and the Zähringen.

A Nation of Four languages

Three-quarters of Switzerland’s people reside in the central lowlands between the Alps and the Jura; more than two-fifths live in cities and towns of more than 10,000 residents. There are some 400 inhabitants per square mile.

The bulk of Switzerland’s income derives from industry, crafts, and tourism, which together employ more than a million people. Only about 7% of the Swiss are engaged in agriculture and forestry, although the country produces about half of its food supply. Switzerland exports engineering, chemical, and pharmaceutical products, as well as world-famous clocks and watches.

The Swiss have a vastly diverse culture. There are four major linguistic and ethnic groups which overlap each other—German, French, Italian, and Romansh. Despite these variations, however, the Swiss have formed a strong national identity.

About 70% of the people speak Swiss-German, or Schwyzerdütsch (Schweizerdeutsch in standard German); about 20% speak French; and about 9% speak Italian, mostly in the southern Ticino region. Approximately 1% speak Romansh, a Rhaeto-Romanic dialect that contains a pre-Roman vocabulary and a substratum of Latin elements; it is believed to be the language of old Helvetia and is spoken mainly by people in the Grisons. Most Swiss speak more than one of the four languages. Many also speak English.

Birth of the Confederation

The Swiss have always guarded their territory jealously. In 1291, an association of three cantons formed the Perpetual Alliance—the nucleus of today’s Swiss Confederation. To be rid of the grasping Habsburgs, the Confederation broke free of the Holy Roman Empire in 1439. It later signed a treaty with France, a rival power, agreeing to provide France with mercenary troops. This led to Swiss fighting Swiss in the early 16th century. The agreement was ended around 1515, and in 1516, the confederates declared their complete neutrality.

The Reformation

The Protestant Reformation created bitter conflicts in Switzerland between those cantons defending papal Catholicism and those embracing the new creed of Protestantism. Ulrich Zwingli, who like Martin Luther had converted from the Catholic faith, led the Swiss Reformation, beginning in 1519. He translated the Bible into Swiss-German and reorganized church rituals. The Protestant movement was spurred by the 1536 arrival in Geneva of John Calvin, who was fleeing Catholic reprisals in France.

Geneva became one of the most rigidly puritanical strongholds of Protestantism in Europe, fervently committed to its self-perceived role as the New Jerusalem. The spread of Calvinism led to the coining of the French term “Huguenot,” a corruption of the Swiss word Eidgenosse (confederate).

After Zwingli died in a religiously motivated battle in 1531, the Swiss spirit of compromise came into play and a peace treaty was signed, allowing each region the right to practice its own faith. Today, 55% of the Swiss define themselves as Protestant, 43% as Roman Catholic, and 2% as members of other faiths.

Despite the deep divisions within the confederation created by the Reformation, the confederates managed to stay together by adopting a pragmatic approach to their religious and political differences. Such an approach to national issues, based on compromise, remains one of the cornerstones of the Swiss political system. Later, during the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48), the Swiss remained neutral while civil wars flared around them.

Industrialization & Political Crises

Turning to economic development, 18th-century Switzerland became the most industrialized nation in Europe. But rapid population growth created social problems, widening the division between the new class of wealth and the rest of the population. Uprisings occurred, but it was only after the French Revolution that they had an effect, causing the Swiss Confederation to collapse in 1798.

Under French guardianship, progressives moved to centralize the constitution of the Swiss Republic. This pull toward centralization clashed with the federalist traditions of the semi-independent cantons. In 1803, Napoleon Bonaparte established a confederation with 19 cantons, but when he fell from power, Swiss conservatives revived the old order. Much of the social progress resulting from the Napoleonic period was reversed and the aristocrats had their former privileges restored to them.

Current Swiss boundaries were fixed at the Congress of Vienna in 1814. In 1848, a federal constitution was adopted and Bern established as the capital.

The federal state, by centralizing responsibility for such matters as Customs and the minting of coins, created conditions favorable to economic progress. The construction of a railway network and the establishment of a banking system also contributed to Switzerland’s development. Both facilitated the country’s export industry, consisting chiefly of textiles, pharmaceuticals, and machinery.

Neutrality through Two World Wars

During World War I (1914–18), Switzerland maintained its neutrality from the general European conflict but experienced serious social problems at home. As purchasing power fell and unemployment rose dramatically, civil unrest grew. One cause of bitterness was that Swiss men conscripted into the army automatically lost their jobs. In 1918, workers, dissatisfied with their conditions, called a general strike, the first and only one in Switzerland’s history. The strike led to the introduction of proportional representation in elections. In the 1920s, a 48-hour workweek was introduced and unemployment insurance was improved.

In 1920, Switzerland joined the League of Nations and provided space for the organization’s headquarters at Geneva. As a neutral member, however, it exempted itself from any military action that the League might take.

In August 1939, on the eve of World War II (1939–45), Switzerland, fearing an invasion, ordered a mobilization of its defense forces. But an invasion never came, even though Switzerland was surrounded by Germany and its allies. It proved convenient to all the belligerents to have, in the middle of a continent in conflict, a neutral nation through which they could deal with each other. It also indicated to Hitler that it was determined to defend itself, and convinced Nazi Germany that any invader would pay in blood for every foot of ground gained in Switzerland.

The sense of neutrality remains so strong that even as recently as 1986, the Swiss voted, in a national referendum, against membership in the United Nations. Switzerland, however, did join the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, (UNESCO), contributing to its Third World development funds.

Switzerland’s political isolationism of the postwar years coincided with a period of unprecedented financial and industrial growth. Many social-welfare programs were introduced, unemployment was virtually wiped out, and the country moved into an enviable position of wealth and prosperity.

Into the Future

In 1992, the Swiss rejected the opportunities offered by the economic integration of Europe, preferring their traditional isolation and neutrality. A referendum in December 1992 vetoed the government’s attempt to seek full membership in the E.U. But the vote was close: 50.3% against and 49.7% in favor.

All six French-speaking cantons backed the plan, while all but one of the German-speaking cantons opposed it. This revealed a rather dangerous split in a multicultural country’s aspirations and political hopes. The plan for European integration was favored not only by the government but also by bankers, labor leaders, intellectuals, and most industrialists. However, it was overwhelmingly rejected by the small rural communities that form much of the Swiss landscape.

In 1996 and 1997, headlines proclaimed Switzerland a banker for Nazi gold. In July 1997, teams from three major U.S. accounting firms moved into 10 Swiss banks to begin an independent inquiry into funds that may have belonged to Holocaust victims.

The Clinton administration accused Switzerland of prolonging World War II by acting as banker to Nazi Germany. But authorities in Bern quickly rejected the accusation as “unsupported” and termed Washington’s assessment “one-sided.” Reeling from these charges, Switzerland faced new accusations that its wartime weapons industry profited from—and favored—Hitler’s Germany in arms trading worth millions of dollars.

The Swiss government ordered its banks to preserve any remaining records of their dealings with Nazi Germany. But in January 1997, a Swiss security guard at the Union Bank of Switzerland halted the destruction of documents from the wartime era, including some that appeared to deal with the forced auctions of property in Berlin during the 1930s.

In 1998, three Swiss banks agreed to pay $1.25 billion to Holocaust survivors, hoping to settle the claims of thousands of survivors whose families lost assets in World War II.

In May 2000 Swiss voters, by a 67% majority, broke with their long-held isolationism and approved agreements with the E.U. that will link this tiny alpine nation more closely with its neighbors. The government hoped that the accords will be a first step toward eventual Swiss membership in the union.

In March 2002, by a slender margin, neutral Switzerland agreed in a countrywide vote to leave behind decades of isolationism and become a member of the United Nations. The referendum passed by a ratio of 54.6% for it and 45.4% against it. The government lobbied hard for Switzerland to shed its go-it-alone stance and become the 190th member of the global body.

Neutral, peace-loving Switzerland a base for Al Qaeda? Impossible, you say. In 2004, the attorney general of Switzerland, Valentin Roschacher, announced that his country has been used as a financial and logistical base by associates of Al Qaeda for plotting terror against the West. Thirteen suspects were arrested, each involved in Islamic “charity” work.

Switzerland celebrated the 50th anniversary of the first voting rights for women in 2007. To show how far women have come since they got the vote, for the first time in Swiss history the country elected a female president, Micheline Calmy-Rey, and a woman speaker of Parliament, Christine Egerszegi-Obrist.

In 2010, women made even greater strides. For the first time, Swiss women captured most of the seats in the country’s seven-member executive branch. The tilt in the balance of power came when the parliament in Bern voted Social Democrat Cabinet member lawmaker Simonette Sommaruga into the cabinet. This female majority made Switzerland the fifth country in the world that year (2010) to have more women than men in the cabinet. These percentages challenged to some degree that traditional notion of a staid and conservative Switzerland being for the most part “governed by committee,” especially since women in Switzerland have recently been polled as generally more liberal than their male counterparts.

New elections in late 2011 will probably focus on economic issues and fiscal policies as Switzerland reacts to the financial crises affecting the banking systems of the U.S. and the rest of Europe.

Dateline

15 B.C. The Romans conquer the Helvetii and other resident alpine tribes.

455 A.D. Barbarian invasions begin.

742–814 Charlemagne incorporates much of what is now Switzerland into his enormous empire.

1291 Three cantons form the Perpetual Alliance, the germ of today’s Swiss Confederation.

1439 The confederation breaks free of the Holy Roman Empire.

1516 The confederates (Eidgenossen) proclaim their neutrality.

1798 The French Revolution brings an invasion of radical forces and ideas, and the old confederation collapses.

1803 Napoleon Bonaparte establishes a new 19-canton confederation, with relatively enlightened social policies.

1814–15 The Congress of Vienna guarantees the national boundaries and neutrality of Switzerland.

1848 The Swiss adopt a federal constitution, still in force today; Bern is recognized as the capital.

1914 Switzerland declares its neutrality at the outbreak of World War I.

1918 Swiss workers stage the only general strike the country has ever known.

1920 Switzerland joins the League of Nations, offering space for a headquarters at Geneva.

1939 Fearing an invasion by Nazi Germany, the country orders a total mobilization of its air and ground forces.

1939–45 Remaining neutral, despite its laundering of Nazi gold, Switzerland becomes a haven for escaping prisoners of war and avoids direct conflicts.

1948 Switzerland introduces broad-based social reforms, including the funding of old-age pensions.

1986 The Swiss electorate votes against membership in the United Nations.

1992 By a close vote, the Swiss reject ties to an economically integrated Europe.

1996–97 Critics around the world attack Switzerland’s role as a World War II banker for the Nazi war effort.

1998 Three Swiss banks agree to a $1.25-billion fund to be distributed among Holocaust victims.

2000 Swiss voters agree to closer E.U. link.

2002 Swiss abandon isolation to join the U.N.

2004 Switzerland called a “terror way station” for Al Qaeda suspects who used the country as a base.

2007 Swiss celebrates 50th anniversary of voting rights for women.

2010 Women take control of executive branch of the government.3 Switzerland’s Art & Architecture

Art

Switzerland’s museums and art collections are known throughout the world. Among them are the Public Art Collection in Basel and the Oskar Reinhart Foundation in Winterthur. Also major are the art museums of Zurich, Bern (including the Klee Foundation), and Geneva, as well as the Avegg Foundation in Bern (Riggisberg) and the Foundation Martin Bodmer (Geneva-Cologny). The Swiss National Museum in Zurich contains valuable exhibits on history and archaeology. There are also museums of church treasures and ethnological displays.

Before about the mid–1700s, the Swiss, a sober and matter-of-fact people, did not regard art with the passion that some of their neighbors did. As a consequence, Swiss painters were not as prominent as those of Italy and France. Sculpture and painting were secondary to architecture, useful only as embellishments to the major work of art, the building itself.

Among the major Swiss artists are Salomon Gessner (1730–88), who painted landscapes and mythological scenes, and Anton Graff (1736–1813), a portraitist. Johann Heinrich Füssl (1741–1825) studied in England, where he became known as Henry Fuseli; he later was appointed keeper of the Royal Academy in London. He is best remembered for his visionary painting The Nightmare.

Angelica Kauffmann (1741–1807) became the country’s most acclaimed neoclassical painter, depicting allegorical, religious, and mythological themes.

Arnold Böcklin (1827–1901) also became widely known in his time. The subjects of his paintings were either extremely light, even frivolous, or else morbidly depressing, as exemplified by his Island of the Dead.

Ferdinand Hodler (1853–1918) was one of the first really significant people to emerge within the world of Swiss art. Some critics have suggested that he “liberated” Swiss painting, making effective use of color and rhythmic tension. His works are displayed in such museums as the National Museum in Zurich and the Museum of Art and History in Geneva. His gargantuan murals, one of which depicts the Retreat of the Swiss Following the Battle of Marignano, remain among his best-known works.

During World War I, Zurich was the setting for the launching of Dadaism. This nihilistic movement, which lasted from about 1916 to 1922, was influenced by the absurdities and carnage of the war. It was based on deliberate irrationality and the rejection of laws of social organization and beauty.

Impressions

[Switzerland is] the land of wooden houses, innocent cakes, thin butter soup, and spotless little inn bedrooms with a family likeness to dairies.

—Charles Dickens

The most famous artist to come out of Switzerland was Paul Klee (1879–1940). He became a member of Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), the German expressionist movement, and worked at the Bauhaus in Weimar. His work is characterized by fantasy forms in line and light-toned colors. Klee also combined abstract elements with recognizable images. Among his better-known works are Mask of Fear, Man on a Tightrope, Pastorale, and The Twittering Machine.

The most distinguished sculptor to emerge from Switzerland was Alberto Giacometti (1901–66). His metal figures, as lean and elongated as figures from an El Greco painting, can be seen in museums throughout the world. After 1930, Giacometti became closely associated with the surrealist movement. His sculpture, exemplified by L’Homme qui marche (Man Walking), is said to represent “naked vulnerability.”

Another eminent sculptor, Jean Tinguely (b. 1925), became known for his kinetic sculptures, which he called “machine sculptures” or “metamechanisms.” Some of these works, including Heureka, are displayed in Zurichhorn Park in Zurich. One of Tinguely’s most controversial creations is La Vittoria, a golden phallus 7.8m long (26 ft.).

Graphic art is another area in which Swiss have distinguished themselves. Today, Switzerland is a center of commercial art and advertising.

Architecture

Switzerland’s architecture has been remarkably well preserved. The country offers superb examples of Roman ruins as well as of medieval churches, monasteries, and castles.

The architecture of Switzerland has always been greatly influenced by the aesthetic development of its neighbors. As a result, it does not have a distinctive “national” style—except in its rural buildings, and perhaps its wood-sided chalets, which have been copied in mountain settings throughout the world.

Much of the country’s earliest architecture was built by the Romans. The ruins at Avenches (Helvetia’s chief town), with its once-formidable 6.4km (4-mile) circuit of walls and 10,000-seat theater, date from the 1st and 2nd centuries A.D.

Many buildings were created during the Carolingian period, including the Augustinian abbey of St. Maurice in the Valais. Considered the most ancient monastic house in Switzerland, it dates from the early 6th century. The Benedictine abbey on the island of Reichenau was launched around 725, and from the early medieval period until the 11th century it was the major cultural and educational center in the country.

Two of Switzerland’s finest examples of Romanesque architecture are the Benedictine Abbey of All Saints, at Schaffhausen (1087–1150), and the Church of St. Pierre de Clages (11th–12th c.). The style of these buildings was followed by the Romanesque-Gothic transitional style of the 12th and 13th centuries, as exemplified by the Cathedral of Chur or by the imposing, five-aisle Minster of Basel.

In the 15th century, Switzerland adopted the Gothic style, as seen in the Cathedral of Notre-Dame at Lausanne and the Cathedral of St. Pierre in Geneva. In 1421, the Minster of Bern was constructed in the late Gothic style, with a three-aisled, pillared basilica; no transepts were added.

With the coming of the Renaissance, there was an increased emphasis on secular buildings. The best town for viewing the architecture of this period is Murten (Morat), with its circuit of walls, fountains, and towers. During the baroque era, no mammoth public buildings were erected. Instead, domestic buildings were adorned with the ornate curves developed in Austria, Italy, and Germany. Many of the elegant town houses that give Bern its distinctive appearance were constructed during this era.

In the 19th century, impressive mansions were built in the neoclassical style. They were mostly those of prosperous merchants eager to evince their wealth.

In the 20th century, Switzerland produced a major architect, Le Corbusier (1887–1965), whose influence extended around the world. Known for his functional approach to architecture and city planning, Le Corbusier believed in adapting a building to the climate and to the convenience of both its construction and its intended use. The majority of his most significant works were erected abroad, in Berlin, Paris, Bordeaux, and Marseille, among other cities.

The principle of functionalism is evident in Switzerland’s rural houses. Each region evolved its own style as it sought to build houses especially suited for retaining heat in the inhospitable, high-altitude Swiss climate. For example, in Appenzell, where it rains a lot, farm buildings were grouped into a single complex. And in the Emmental district, a large roof reached down to the first floor on all sides of the building.

Impressions

[Switzerland is] small, and like everything within it, so clean that you can hardly breathe for hygiene, and oppressive precisely because everything is right, fitting, and respectable. . . . Everything in this country is of an oppressive adequacy.

—Max Frisch

From Carl Jung to Paul Klee, Switzerland’s famous people

Ernest Ansermet (1883–1969) This Swiss conductor achieved fame with Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe in 1915. In 1918, Ansermet founded what was to become one of Switzerland’s most respected orchestras, the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, in Geneva, and introduced many new works that later became famous. He frequently conducted musical tours of the United States.

Arnold Böcklin (1827–1901) His paintings of mythical scenes and landscapes are displayed in galleries throughout Europe. Among his most famous works are The Elysian Fields, The Sacred Grove, and The Island of the Dead. Böcklin used color imaginatively and developed his mythological portrays with great originality.

Jean Henri Dunant (1828–1910) Co-winner of the first Nobel Peace Prize, in 1901, this Swiss humanitarian was the founder of the Red Cross. Greatly affected by his role in caring for the injured soldiers at the Battle of Solferino (Italy, 1859), he later wrote A Souvenir of Solferino. In it, he called for an international organization, without political ties, to aid the wounded in future conflicts. His proposal eventually led to the Geneva Convention governing the treatment of combatants and to the establishment of the International Red Cross.

Friedrich Dürrenmatt (1921–90) This Swiss playwright is best known for his grotesque farce The Visit, which was filmed with Ingrid Bergman and Anthony Quinn. The Physicists, a mordant satire, was also acclaimed. In it, Dürrenmatt chose as his theme the danger posed by one person’s possession of nuclear and nuclear-related technology.

Leonard Euler (1707–83) One of the originators of pure mathematics, Eurler, who was born in Basel, was invited by Catherine the Great to study and teach in Russia. Euler discovered the law of quadratic reciprocity (1772) in the theory of numbers. His study of the lines of curvature (1760) led to the new branch of differential geometry. Euler conducted massive research in algebra, trigonometry, calculus, and geometry and made discoveries in astronomy, hydrodynamics, and optics.

Alberto Giacometti (1901–66) This Swiss sculptor’s works are characterized by surrealistically elongated forms and are filled with what critics have called “hallucinatory moods.” During his early career, Giacometti worked as a painter; in later life, he returned to painting, but his works reflected a sculptural quality, according to critics.

Carl Jung (1875–1961) This Swiss psychologist and psychiatrist became the founder of analytic psychology. An early associate of Freud, Jung developed concepts of extrovert and introvert personalities and of the collective unconscious. Greatly influenced by artistic and archetypal themes held in common by many primitive societies, he stressed an active role for an analyst during the therapeutic process.

Paul Klee (1879–1940) Swiss modernist painter, he was one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. Combining abstract elements with recognizable images, Klee painted in a style characterized by fantasy figures in line and light colors. His works are displayed in galleries of modern art all over the world. He was also an accomplished musician.

Le Corbusier (1887–1965) This Swiss architect helped revolutionize international concepts in city planning and functional architecture. Le Corbusier designed his first house at 18 and later became famous for his buildings in Berlin, Marseille, and other cities. In 1950, he contributed to the design of the United Nations Secretariat Building in New York. He also was in charge of the design of the Visual Art Center at Harvard University. Although famous primarily for his work as an architect (he was reputedly a master at the unusual applications of molded concrete), Le Corbusier was also well known as an abstract painter.

Ulrich Zwingli (1484–1531) A Swiss religious reformer, Zwingli was a Catholic priest before becoming a Protestant minister. Enraged by the values of the 16th-century popes, he led the Protestant Reformation in Switzerland from 1519 until his death. The movement was later bolstered by the arrival of John Calvin in 1536. Zwingli translated the Bible into Swiss German and wrote a testament of Protestant teachings, On the True and False Religion. His influence helped transform Geneva into central Europe’s most stalwart bastion of 16th-century Protestantism. Zwingli died in Kappel, near Zurich, in a religious war between Catholics and Protestants.

The Lay of the Land

This mountainous, landlocked alpine country is surrounded by Austria, France, Italy, and Germany, and is one of the smallest countries in Europe, stretching only 220km (137 miles) north to south and 350km (217 miles) east to west.

Zurich and Geneva are its leading cities, and much of the northern border with Germany follows the course of the Rhine River. In the east, Lake Constance forms a border with both Germany and Austria. In the southwest, Switzerland shares a border with France that cuts across Lake Geneva.

The little country is divided in a trio of regions, including the Swiss Alps, the Swiss plateau, and the Jura. Most residents live on the plains and rolling hills of the plateau. The Alps are the biggest tourist attraction, reaching their highest peak at Dufourspitze at 4,634m (15,200 ft.), a formation which straddles the Italian-Swiss border. The highest mountain lying entirely within the boundaries of Switzerland is the Dom, rising to a summit of 4,545m (14,908 ft.). The Alps cover 65% of the surface of the country.

Skiing and other winter sports provide a large slice of the Swiss economy. The major resorts for this type of fun in the snow lie in the Valais, Bernese Oberland, and the Grisons. Many villages, such as Zermatt, are free of vehicular traffic, and most of these main regions can be reached within 3 hours of Switzerland’s main cities.

The more populated Swiss plateau runs from Lake Geneva on the French border, cutting across central Switzerland to Lake Constance, which, as mentioned, is shared with Germany and Austria.

Most of the large lakes, including Lake Geneva, are located in the plateau. The only large lake that lies entirely within Switzerland is Lake Neuchâtel, at 218 sq. km (85 sq. miles). Three great rivers—the Rhône, Rhine, and Aare, cross this great plateau, which occupies about one-third of the landmass of Switzerland.

Accounting for 12% of the landmass, the Jura is a limestone range running from Lake Geneva to the Rhine River. The name “Jurassic” comes from this region, because many fossils and dinosaur tracks have been found here.

In hydrography, Switzerland has 6% of all freshwater reserves in Europe, and is the source of several major rivers such as the Rhine and Aare that flow into the North Sea. The Rhône empties into the Mediterranean.

In general, about one-fourth of Switzerland is mountains, lakes, or rivers, with farming taking up around 35% of the land.

In all, 50,000 plant and animal species call Switzerland home. Once there were more. Because of city and agricultural growth in the plateau, and the elimination of many habitats, many species here are now endangered. To prevent further erosion, Switzerland is setting aside protected natural areas.

Switzerland in Pop Culture

Books

Read a few of the books below to get a feel for Switzerland—its people, atmosphere, and history—before you visit.

• The Apple and the Arrow (Conrad Buff) is told from the point of view of William Tell’s young son Walter, and recounts the 1291 Swiss struggle for freedom.

• Arms and the Man (George Bernard Shaw), a play first produced in 1894, takes place during the 1885 Serbo-Bulgarian War. It features a Swiss voluntary soldier who carries chocolates instead of pistol cartridges. Oscar Straus based his 1909 The Chocolate Soldier operetta on this play.

• Daisy Miller (Henry James), a novella, probes the emotional complications of a rich American traveling in Switzerland. Published in 1878, the novella became one of James’s all-time big successes.

• Heidi (Johanna Spyri), a world classic, is the best-known book set in Switzerland. Charming readers of every generation since its publication in 1880, it’s the story of a young orphan sent to live with her grumpy grandfather in the Swiss Alps.

• Hotel du Lac (Anita Brookner) is the story of a romance author who has been banished by her friends to a stately hotel in Switzerland, where she hears fascinating tales of the guests she befriends there.

• The Magic Mountain (Thomas Mann) is a classic, one of the most celebrated novels of the 20th century, and it’s set in an alpine sanatorium in the resort of Davos-Platz. Mann tells the story of Hans Castorp, a “modern everyman,” who spends 7 years in the alpine sanatorium for TB patients before leaving to become a soldier in World War I.

• Scrambles Amongst the Alps (Edward Whymper) is the latest reprint of this classic mountaineer’s account of his conquest of the Matterhorn.

• For some light reading, Ticking Along with the Swiss (Dianne Dicks) is an amusing collection of personal tales from travelers to Switzerland.

• A Tramp Abroad (Mark Twain) is the eternal tongue-in-cheek travelogue for “Innocents Abroad” touring the Swiss Alps.

• Walking Switzerland—The Swiss Way (Marcia and Philip Lieberman) is a useful guide for those who want to walk through the tiny country.

• Why Switzerland? (Jonathan Steinberg) provides the best look at Swiss society, culture, and history.

• Wilhelm Tell (Friedrich von Schiller), a play, is one of the Harvard Classics. It’s based on the legendary Swiss hero who resisted Austrian domination. He was consequently forced to use a bow and arrow to shoot an apple placed on the head of his son. Rossini based his famous opera on this play.

Films

Switzerland is not Hollywood, not even a Bollywood. But the dramatic geography of the country itself has often made it a locale for filmmakers from all over the world. Of course, the all-time Swiss classic is Heidi, shot in 1937 and starring Shirley Temple as Heidi.

One of the best James Bond films, Goldfinger (1964), uses Switzerland in some of its backdrop scenes with star Sean Connery. Secret Agent 007 returned to Switzerland for more background scenes in the 1969 On Her Majesty’s Secret Service and the 1995 Goldeneye. The 1994 version of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, directed by Kenneth Branagh, also used dramatic Swiss backdrops.

Trois couleurs: Rouge (Three Colors Red) in 1994, the last film in director Krzysztof Kieslowski’s trilogy, used scenes in Geneva’s Old Town as a backdrop, and director Peter Greenaway also used the city in his Stairs 1 Geneva (1995).

Director Blake Edwards used Gstaad and its swanky Palace Hotel for The Return of the Pink Panther (1975). The Bernese Oberland is showcased, perhaps as never before, in Clint Eastwood’s The Eiger Sanction (1975). Even people who didn’t enjoy this espionage spy thriller were charmed by the scenery. A Zurich bank figures into the plot of The Bourne Identity (2002), starring Matt Damon. The thriller is based very loosely on Robert Ludlum’s novel.

The literary tradition of Switzerland

Many 19th-century English writers went to Switzerland for inspiration. Prominent among them were Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (who wrote Frankenstein beside Lake Geneva), Lord Byron, Robert Browning, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Charles Dickens. In the 20th century, Thomas Mann, James Joyce, Hermann Hesse, and Vladimir Nabokov were some of the major writers who gravitated to Switzerland.

Of course, Switzerland has fine literature of its own. Because of the country’s different languages, much of Swiss literature has had strong connections with literary traditions and styles in Germany and Austria, in France, and in Italy. Literature produced solely in Switzerland, with few international influences, is usually written in the Rhaeto-Romanic group of local dialects, among them Romansh.

It wasn’t until the 18th century that Swiss literature became defined as such. The most important works—except for those by the Geneva-born Rousseau—were written in German. Among them, the most famous is the Codex Manesse, first published in 1732 (the manuscript is preserved in Heidelberg). It is a collection of the works of 30 poets, known collectively as the Minnesingers. In the 19th century, Switzerland’s national man of letters, Gottfried Keller, made the Codex the subject of one of his Zurich novellas.

Writers who emerged in the 18th century include Albrecht von Haller (1708–77), who wrote voluminous works on physiology and other scientific subjects, and Johannes von Müller (1752–1809), whose History of the Swiss Confederation inspired von Schiller to write William Tell.

In the 1800s, two Swiss works were translated around the world. They were Heidi (1880), by Johanna Spyri, and The Swiss Family Robinson (1813), by Johann David Wyss.

Jacob Christoph Burckhardt (1818–97), one of the preeminent historians of the 19th century, is known for his great classic, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (1860). Burckhardt’s emphasis on the cultural interpretation of history influenced the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche.

Gottfried Keller (1819–90), novelist, poet, and short-story writer, reigned supreme over Swiss literature in the latter part of the 19th century. His works, particularly Der grüne Heinrich (Green Henry) and People of Seldwyla, are still popular throughout the German-speaking world.

The last German-language poet of international reputation born in Switzerland was Carl Spitteler (1845–1924), whose major allegorical work, Olympischer Frühling (Olympian Spring), published before World War I, argued for the need of ethics in the modern world. Spitteler was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 1919.

French-Swiss literature is dominated by two towering figures, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–78), the father of Continental Romanticism and author of The Social Contract and the autobiographical Confessions, and Germaine (Madame) de Staël (1766–1817), who conducted a famous salon in Paris. During the French Revolution, de Staël sought refuge at the family estate at Coppet, on the shore of Lake Geneva. Her principal work, De l’Allemagne (On Germany, 1810), was an encomium of German romanticism. In 1811, she was exiled from France by Napoleon, who objected to the book; she found comfort in her marriage to a young Swiss officer more than 20 years her junior.

In the 20th century, two Swiss literary figures gained an international following. One is Friedrich Dürrenmatt (1921–90), who is known mainly for his plays The Visit and The Physicists. The other is Max Frisch (1911–91), who has achieved a place in contemporary German literature with his plays, among them Andorra and The Firebugs, and his novels. His most famous novel is I’m Not Stiller, a trenchant critique of Swiss smugness and isolationism.

Music

For most of its history, religious and folk music has dominated this art form in Switzerland. Traditional instruments included the hammered dulcimer, the fife, the bagpipe, the cittern, the shawm, and the hurdy-gurdy.

Beginning in 1836, the accordion swept the country. The Swiss quickly incorporated this instrument into their folk music.

As more and more Swiss moved to the cities, folk music from rural areas was mixed with jazz and the foxtrot, with the saxophone coming into great prominence.

By the 1960s, trios of two accordions and a double bass ruled the night.

The rural Appenzell region in northeastern Switzerland remains the major center for folk music today.

Pop and rock invaded Switzerland in the 1960s, much to the horror of traditionalists. Swiss musicians like Les Aiglons or Les Faux Frères became major recording artists. Swiss rock began to die out in the late ’60s, replaced by more progressive music such as jazz and blues.

Hard rock appeared by the end of the ’70s, and a rock band called Krokus became the most popular recording group in the history of Swiss music.

Metal bands dominated music in the 1980s, with a Swiss band, Celtic Frost, the leader of the pack. Swiss new-wave bands began to branch out and become internationally known. Fame came to such bands as Kleenex/LiliPUT and Yello.

Rappers and DJs arrived on the scene in the ’90s, including Black Tiger from Basel, the first one to rap in a Swiss-German dialect. Birthed in the 1990s, the band Gotthard survived the millennium to become the leading Swiss rock group and one of the most acclaimed bands in western Europe.

From Yodeling to raclette parties

It has often been said that there is really no such thing as Swiss music per se, just music in Switzerland performed by Swiss musicians. There is some validity to this view. Except for its alpine melodies and dance music, Switzerland has made only a modest contribution to the world’s repertoire.

Yet, Switzerland has several excellent orchestras and opera companies. The Zurich Opera specializes in German-language productions, and the Grand Théatre de Genéve, the country’s leading opera house, has a predominantly French-language repertoire. The Orchestre de la Suisse Romande is the country’s best-known orchestra, and the respected Tonhalle Orchester of Zurich has a loyal following.

Local cultural entertainment is highlighted by the folk music and dancing of the alpine regions, which you can also see and hear in the big cities. These include Kuhreigen (round dances), yodeling performances, and a style of dance tunes known as Ländler, performed by small orchestras, whose members usually appear in regional costumes.

Switzerland’s cities offer a variety of evening entertainment. In Zurich, the traditional stomping grounds for night owls lie around the Niederdorf, a neighborhood within Old Town known for its strip joints, bars, and music halls. There’s even a red-light district. Most nightclubs, however, close at 2am, and many of them seem sterile and a bit boring. Geneva, too, despite its Calvinist traditions, has a sophisticated nightlife.

It might be more interesting, especially if you’re a first-time visitor, to patronize some of the local folkloric places, where you can see and hear yodeling and dancing to alpine music.

Theater presentations tend to be in German or French, so unless you speak either language, these shows may not be for you.

Throughout the winter, the après-ski life in Switzerland’s high-altitude resorts might best be described as vigorous, with raclette parties, beer drinking in rustic taverns, sleigh rides, and lots of music, much of it brought in by live groups from Great Britain, France, and Germany or from the United States.

Many after-dark rendezvous joints close down in summer. The Swiss prefer to drink outside, under the summer sky, perhaps in some beer garden, rather than being cooped up inside a deliberately darkened disco.

Eating & Drinking

Swiss cuisine is a flavorful blend of German, French, and Italian influences. In most restaurants and hotel dining rooms today, menus will list a wide array of international dishes, but you should make an effort to sample some of the local fare.

Cheese

Cheese making is part of the Swiss heritage. Cattle breeding and dairy farming, concentrated in the alpine areas of the country, have been associated with the region for 2,000 years, since the Romans ate caseus Helveticus (Helvetian cheese). In fact, the St. Gotthard Pass was a well-known cattle route to the south as far back as the 13th century.

Today, more than 100 varieties of cheese are produced in Switzerland. The cheeses, however, are not mass produced—they’re made in hundreds of small, strictly controlled dairies, each under the direction of a master cheese maker with a federal degree.

The cheese with the holes, known as Switzerland Swiss or Emmentaler, has been widely copied, since nobody ever thought to protect the name for use only on cheeses produced in the Emme Valley until it was too late. Other cheeses of Switzerland, many of which have also had their names plagiarized, are Gruyère, appenzeller, raclette, royalp, and sapsago. The names of several mountain cheeses have also been copied, including sbrinz and spalen, closely related to the caseus Helveticus of Roman times.

Fondue

Cheese fondue, which consists of cheese (Emmentaler and natural Gruyère used separately, together, or with special local cheeses) melted in white wine flavored with a soupçon of garlic and lemon juice, is the national dish of Switzerland. Freshly ground pepper, nutmeg, paprika, and Swiss kirsch are among the traditional seasonings. Guests surround a bubbling caquelon (an earthenware pipkin or small pot) and use long forks to dunk cubes of bread into the hot mixture. Other dunkables are apples, pears, grapes, cocktail wieners, cubes of boiled ham, shrimp, pitted olives, and tiny boiled potatoes.

Raclette

This cheese specialty is almost as famous as fondue. Popular for many centuries, its origin is lost in antiquity, but the word “raclette” comes from the French word racler, meaning “to scrape off.” Although raclette originally was the name of the dish made from the special mountain cheese of the Valais, today it describes not only the dish itself but also the cheese varieties suitable for melting at an open fire or in an oven.

A piece of cheese (traditionally half to a quarter of a wheel of raclette) is held in front of an open fire. As it starts to soften, it is scraped off onto one’s plate with a special knife. The unique flavor of the cheese is most delicious when the cheese is hottest. The classic accompaniment is fresh, crusty, homemade dark bread, but the cheese may also be eaten together with potatoes boiled in their skins, pickled onions, cucumbers, or small corncobs. You usually eat raclette with a fork, but sometimes you may need a knife as well.

Other Regional Specialties

The country’s ubiquitous vegetable dish is röchti or rösti (hash-brown potatoes). It’s excellent when popped into the oven coated with cheese, which melts and turns a golden brown. Spätzli (Swiss dumplings) often appear on the menu.

Lake fish is a specialty in Switzerland, with ombre (a grayling) and ombre chevalier (char) heading the list—the latter a delectable but expensive treat. Tasty alpine lake fish include trout and fried filets of tiny perch.

Country-cured sausages can be found at open markets around the country. The best known is called bündnerfleisch, a specialty in the Grisons. The meat, however, is not cured, but dried in the crisp, dry alpine air. Before modern refrigeration, this was the Swiss way of preparing meat for winter consumption.

The Bernerplatte is the classic provincial dish of Bern. If you order this typical farmer’s plate, you’ll be confronted with a mammoth pile of sauerkraut or French beans, topped with pigs’ feet, sausages, ham, bacon, or pork chops.

In addition to cheese fondue, you may enjoy fondue bourguignonne, a dish that has become popular around the world. It consists of chunks of meat spitted on wooden sticks and cooked in oil or butter, seasoned according to choice. Also, many establishments offer fondue chinoise, made with thin slices of beef and Oriental sauces. At the finish, you sip the broth in which the meat was cooked.

Typical Ticino specialties include risotto with mushrooms and a mixed grill known as fritto misto. Polenta, made with cornmeal, is popular as a side dish. Ticino also has lake and river fish, such as trout and pike. Pizza and pasta have spread to all provinces of Switzerland; either one is often the most economical dish on the menu.

Salads often combine both fresh lettuce and cooked vegetables, such as beets. For a unique dish, ask for a zwiebelsalat (cooked onion salad). In spring, the Swiss adore fresh asparagus. In fact, police have been forced to increase their night patrols in parts of the country to keep thieves out of the asparagus fields.

The glory of Swiss cuisine is its patisseries, little cakes and confections served all over the country in tearooms and cafes. The most common delicacy is gugelhupf, a big cake shaped like a bun and traditionally filled with whipped cream.

Drinks

White wine is the invariable choice of beverage with fondue; if you don’t like white wine, you might get by with kirsch or tea.

There are almost no restrictions on the sale of alcohol in Switzerland, but prices of bourbon, gin, and scotch are usually much higher than in the United States, and portions can be skimpy.

Wine

Swiss wines are superb. Unlike French wines, they are best when new. Many wines, such as those from the Lake Geneva region, are produced for local consumption. Ask your waiter for advice on which local wine to try.

Most of the wines produced in Switzerland are white, but there are also good rosés and fragrant red wines. Most exported wines are produced in the Valais, Lake Geneva, Ticino, and Seeland. However, more than 300 small winegrowing areas are spread over the rest of the country, especially where German dialects are spoken.

In the French-speaking part of Switzerland, two of the best wines are the fruity Fendant and the slightly stronger Johannisberg. In the German-speaking part, you might want to sample one of the dry and light reds, which include Stammheimer, Klevner, and Hallauer. In the Italian-speaking Ticino, red merlot is a fruity wine with a pleasant bouquet.

Beer

Swiss beer is an excellent brew; it’s the preferred drink in the German-speaking part of the country. Helles is light beer; Dunkles is dark beer.

Liqueur

Swiss liqueurs are tasty and highly potent. The most popular are kirsch (the national hard drink, made from the juice of cherry pits), and Pflümli (made from plums). Williamine is made from fragrant Williams pears. Träsch is another form of brandy, made from cider pears. In the Ticino, most locals are fond of the fiery Grappa brandy, which is distilled from the dregs of the grape-pressing process.

Chocolate superpower

Cocoa beans are chocolate’s raw ingredients. First publicized in Europe by Columbus, who noticed them growing on trees in Nicaragua in 1502, they were traded as currency by the conquistadores in the New World, who viewed them as an elixir of physical strength. Back in Spain, royal cooks mixed the pulverized beans with sugar and hot water and served them with great success to the royal family. The Spanish-born Anne of Austria introduced it to the French court at her dinner parties after her marriage to Louis XIII. And in a kind of chain reaction to the bean’s original “discovery,” London’s first chocolate shop was established by a Frenchman in 1657.

Nineteenth-century attitudes about chocolate (as perceived in North America and in Europe) were widely different. In 1825, the leading culinarian of the French-speaking world (Brillat-Savarin) declared that chocolate was one of the most effective restoratives of physical and intellectual powers known to man. In contrast, Harriet Beecher Stowe, the American-born moral crusader and woman of letters, declared chocolate unfit for proper American tables, and—in a burst of prudishness—commented suspiciously on its French and Spanish origins.

Despite Ms. Stowe’s invectives, the market for chocolate continued to grow. This fact was immediately noticed by the canny Swiss from their politically neutral bastion in the Alps.

From the early 1800s, the Swiss began investing heavily in what they perceived as a long-range moneymaker. Pioneers of the industry opened the country’s first chocolate factory in 1819 at Corsier, near Vevey. What’s now a massive multinational concern, Suchard, was established near Neuchâtel in 1824. In 1875, Swiss-born Daniel Peter invented milk chocolate by adding condensed milk to his brew of pulverized cocoa and sugar. In 1879, the first chocolate bar was created (the Lindt Surfin bar). In 1899, the Sprungli and Lindt empires merged into a Zurich-based chocolate-making dynasty. The Tobler and Nestlé organizations were founded shortly afterward.

Switzerland today is the largest chocolate superpower in the world, leading the globe in production. Both secrecy and precision have always been cited as Swiss virtues, and both of these qualities are required during a complicated blending process that transforms the raw ingredients into the final product. The allure is aesthetic as well as gastronomic: Swiss consumers expect new artwork on their chocolate wrappers at frequent intervals, and an army of commercial artists labors at yearly intervals to comply. The Swiss eat and drink more chocolate per capita than any other nation in the world, fueling their bodies for the bone-chilling temperatures of the alpine climate. (No self-respecting mountain climber ever embarks without the requisite chocolate bars.) Swiss factories maintain “chocolate breaks” for sugar-induced bursts of energy, and swiss housewives usually don’t buy less than a kilo of chocolate at a time.

When to Go

Low-season airfares are usually offered from November 1 to December 14 and from December 25 to March 31. Fares are slightly higher during shoulder season (during Apr and May, and from Sept 16 to the end of Oct). High-season fares apply the rest of the year (June–Sept 15), presumably when Switzerland and its landscapes are at their most hospitable and most beautiful.

Keep in mind that it’s most expensive to visit Swiss ski resorts in winter, and slightly less so during the rest of the year. Conversely, it’s cheaper to visit lakeside towns and the Ticino in winter. Cities such as Geneva, Zurich, and Bern don’t depend on tourism as a major source of capital, so prices in these cities tend to remain the same all year.

The Weather

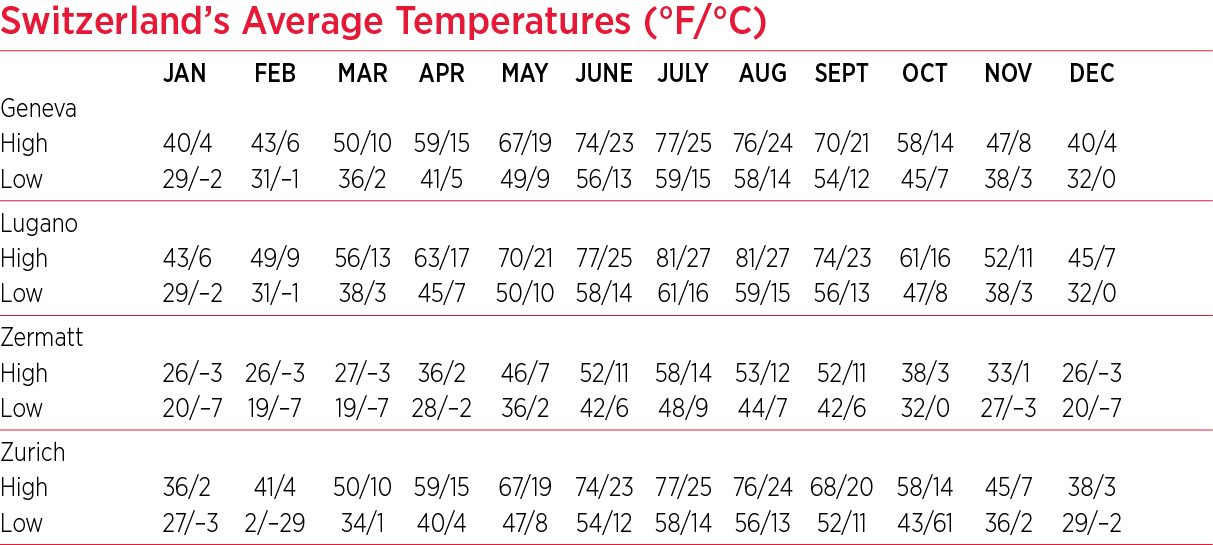

The temperature range is about the same as in the northern United States, but without the extremes of hot and cold. Summer temperatures seldom rise above 80°F (26°C) in the cities, and humidity is low. Because of clear air and lack of wind in the high alpine regions, sunbathing is sometimes possible even in winter. In southern Switzerland, the temperature remains mild year-round, allowing subtropical vegetation to grow.

Switzerland Calendar of Events

The festivals mentioned in this section, unless otherwise specified, fall on different dates every year. Inquire at the Swiss National Tourist Office or local tourist offices for an updated calendar. See “The Best Festivals” in chapter 1 for more information. For an exhaustive list of events beyond those listed here, check http://events.frommers.com, where you’ll find a searchable, up-to-the-minute roster of what’s happening in cities all over the world.

January

Vogel Gryff Festival (The Feast of the Griffin), Basel. The “Wild Man of the Woods” appears on a boat, followed by a mummers’ parade. For more information, call  061/268-68-68 or see www.basel.com/en. Mid-January.

061/268-68-68 or see www.basel.com/en. Mid-January.

February

Basler Fasnacht, Basel. Called “the wildest of carnivals,” with a parade of “cliques” (clubs and associations). For more information, call  061/268-68-68 (www.fasnacht.ch). First Monday after Ash Wednesday.

061/268-68-68 (www.fasnacht.ch). First Monday after Ash Wednesday.

March

Hornussen (“Meeting on the Snow”), Maloja. A traditional sport of rural Switzerland. For information, call  081/824-31-81 or see www.MySwitzerland.com/festivals. For a description of the sport, see the box “Hornussen, Schwingen & Waffenlaufen,” later in this chapter. Mid-March.

081/824-31-81 or see www.MySwitzerland.com/festivals. For a description of the sport, see the box “Hornussen, Schwingen & Waffenlaufen,” later in this chapter. Mid-March.

April

Primavera Concertistica, Locarno. April marks the beginning of a festival of music concerts that lasts through October. For information, call  091/791-00-91 or visit www.sbt.ti.ch. Mid-April.

091/791-00-91 or visit www.sbt.ti.ch. Mid-April.

Sechseläuten (Six O’Clock Chimes), Zurich. Members of all the guilds dress in costumes and celebrate the arrival of spring, which is climaxed by the burning of Böögg, a straw figure symbolizing winter. There are also children’s parades. The Zurich Tourist Office ( 044/215-40-00; www.zuerich.com) shows the parade route on a map. (Böögg is burned at 6pm on Sechseläutenplatz, near Bellevueplatz.) Third Monday of April.

044/215-40-00; www.zuerich.com) shows the parade route on a map. (Böögg is burned at 6pm on Sechseläutenplatz, near Bellevueplatz.) Third Monday of April.

May

Corpus Christi. Solemn processions in the Roman Catholic regions and towns of Switzerland. End of May.

June

Fête de Lausanne, Lausanne. Beginning of an international festival, showcasing weeks of music and ballet. For information, call  021/315-22-14 (www.lausanne.ch). End of June.

021/315-22-14 (www.lausanne.ch). End of June.

William Tell Festival, Interlaken. Performances of the famous play by Schiller. For more information, call  033/822-37-32 (www.tellspiele.ch). End of June through early September.

033/822-37-32 (www.tellspiele.ch). End of June through early September.

July

Montreux International Jazz Festival, Montreux. More than jazz, this festival features everything from reggae bands to African tribal chanters. Monster dance fests also break out nightly. The festival concludes with a 12-hour marathon of world music. For more information, call  021/966-44-44 (www.montreuxjazz.com). Lasts 2 weeks and is held in the beginning of July.

021/966-44-44 (www.montreuxjazz.com). Lasts 2 weeks and is held in the beginning of July.

Züri Fäscht, Zurich. This summertime citywide festival takes over Zurich with fairground revelry. Held every 3 years in early July; the next one, pending the resolution of security issues and uncertainty about the construction plans for the site where the event traditionally takes place, will occur in 2013.www.zuerifaescht.ch.

August

Fêtes de Genève, Geneva. Highlights are flower parades, fireworks, and live music all over the city. For more information, call  022/909-70-70 (www.fetes-de-geneve.ch). Early August.

022/909-70-70 (www.fetes-de-geneve.ch). Early August.

Lucerne Festival, Lucerne. Concerts, theater, art exhibitions, and street musicians. For more information, call  041/226-44-80 (www.lucernefestival.ch). Mid-August through mid-September.

041/226-44-80 (www.lucernefestival.ch). Mid-August through mid-September.

Zurich Street Parade. Visitors flock to Zurich for a daylong techno/dance party and parade that takes over the entire city. You’ll either want to book a hotel far in advance, or avoid this at all costs. Visit www.streetparade.ch. See the "Zurich Street Parade" box in Chapter 4 for details. Early to mid-August.

October

Autumn Festival, Lugano. A parade and other festivities mark harvest time. Little girls throw flowers from blossom-covered floats and oxen pull festooned wagons in a colorful procession. For information, call  091/913-32-32 or visit www.lugano-tourism.ch. Early October.

091/913-32-32 or visit www.lugano-tourism.ch. Early October.

Aelplerchilbi, Kerns and other villages of the Unterwalden Canton. Dairymen and pasture owners join villagers in a traditional festival to mark the end of an alpine summer. For more information, contact the Sarnen Tourismus, Hofstrasse 2 ( 041/666-50-40; www.sarnen-tourism.ch). Late September or October.

041/666-50-40; www.sarnen-tourism.ch). Late September or October.

November

Zibelemärit, Bern. The famous “onion market” fair. Call  031/328-12-12 or visit http://www.berninfo.com/en for more information. Fourth Monday in November.

031/328-12-12 or visit http://www.berninfo.com/en for more information. Fourth Monday in November.

December

Christmas Festivities. Ancient St. Nicholas parades and traditional markets are staged throughout the country to mark the beginning of Christmas observances, with the major one at Fribourg. Mid-December.

L’Escalade, Geneva. A festival commemorating the failure of the duke of Savoy’s armies to take Geneva by surprise on the night of December 11, 1602. Brigades on horseback in period costumes, country markets, and folk music are interspersed with Rabelaisian banquets, fife-and-drum parades, and torch-lit marches. Geneva’s Old Town provides the best vantage point. Call  022/909-70-11 or visit www.escalade.ch for more information. Three days and nights (nonstop) in early December.

022/909-70-11 or visit www.escalade.ch for more information. Three days and nights (nonstop) in early December.

Responsible Travel

Perhaps more so than any other people in the world, the Swiss have been sensitive to protecting their environment. In addition to the oldest and wildest national park of Europe, many newly opened regional nature parks are being set aside for future generations.

Believe it or not, Switzerland even has volunteer “mountain cleaners,” who sweep the landscape looking for garbage that careless tourists have left behind.

The country is also looking to the future, and many hotels plan to follow the example set by the Hotel Europa in St. Moritz. At this establishment, the largest solar plant of any hotel in Switzerland was inaugurated. The solar energy collected on the hotel’s roof feeds both the hot water and heating systems as well as the pool. Not only are high energy costs counteracted, so are carbon dioxide emissions.

City tourist offices are even issuing “greenie points.” Take Zurich tourist officials, for example. They are recommending that visitors take the train from London via Paris instead of flying to Zurich. It is estimated that this travel by train will save 176 kilograms of carbon dioxide emissions per person for the 966km (600-mile) journey.

Eco-tourism is the buzzword of the day, and more and more Swiss environmentalists are talking about keeping their splendid alpine peaks pristine. They need the words of critic John Ruskin, who said, “Mountains are the beginning and end of all natural scenery.”

Swiss ecologists must guard against the impact of unbridled ski-lift development and exhaust fumes from motorized traffic, especially transalpine trucking.

The Swiss also fear the spread of vacation apartments springing up like a tourist housing sprawl, such as around Pontresina. The sprawl also plagues such neighboring resorts as St. Moritz and other vacation centers in the Upper Engadine.

In Davos, one of the most famous of all ski resorts, visitors are urged not to drive cars into town, but take one of the fleet of buses moving skiers in winter or hikers in summer to the mountains.

For a true eco-friendly holiday, consider a stay on a Swiss farm, getting close to nature. Prices are lower than at most hotels, and you even have the option of working in the fields. For this type of holiday, check with the Schweizerischer Bauernverband (Swiss Farmers Association) at Laurstrasse 10, CH-5200 Brugg ( 056/462-25-1110), or Verein Ferien auf dem Bauernhof (Swiss Holiday Farms Association) at Reka, Neuengasse 15, 3000 Bern (

056/462-25-1110), or Verein Ferien auf dem Bauernhof (Swiss Holiday Farms Association) at Reka, Neuengasse 15, 3000 Bern ( 031/329-66-99; www.bauernhof-ferien.ch).

031/329-66-99; www.bauernhof-ferien.ch).

You can find eco-friendly travel tips, statistics, and touring companies and associations—listed by destination under “Your Travel Choice”—at the TIES website, www.ecotourism.org. Also check out Conservation International (www.conservation.org)—which, with National Geographic Traveler, annually presents World Legacy Awards to those travel tour operators, businesses, organizations, and places that have made a significant contribution to sustainable tourism. Ecotravel.com is part online magazine and part eco-directory that lets you search for touring companies in several categories (water based, land based, spiritually oriented, and so on).

The Association of British Travel Agents (ABTA; www.abta.com) acts as a focal point for the U.K. travel industry and is one of the leading groups spearheading responsible tourism.

General Resources for green travel

In addition to the resources for Switzerland listed above, the following websites provide valuable wide-ranging information on sustainable travel. For a list of even more sustainable resources, as well as tips and explanations on how to travel greener, visit www.frommers.com/planning.

• Responsible Travel (www.responsibletravel.com) is a great source of sustainable travel ideas; the site is run by a spokesperson for ethical tourism in the travel industry. Sustainable Travel International (www.sustainabletravelinternational.org) promotes ethical tourism practices, and manages an extensive directory of sustainable properties and tour operators around the world.

• In the U.K., Tourism Concern (www.tourismconcern.org.uk) works to reduce social and environmental problems connected to tourism. The Association of Independent Tour Operators (AITO; www.aito.co.uk) is a group of specialist operators leading the field in making holidays sustainable.

• In Canada, www.greenlivingonline.com offers extensive content on how to travel sustainably, including a travel and transport section and profiles of the best green shops and services in Toronto, Vancouver, and Calgary.