CHAPTER 16

Will The Real Joan Robin Please Stand Up?

I DREAMED I HAD REACHED the ninth wicket, my final destination on the croquet course. I aimed, took a deep, optimistic gulp, and clonk!—propelled my bright yellow ball directly through the stake with my mallet.

“I won! I think I won!” I exclaimed while executing impressive victory leaps around my triumphant wooden ball. “Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah,” I gloated.

“Not so fast.” Dad was tallying up the points—25 for me, 24 for mom. “Mommy still gets her last turn.” Behind me, my mother puffed a breath of magic into her hands and rubbed them together for the kill. She re-adjusted her feet and hips three times, eyeballing the trajectory from her ball to the final wicket with steely eyes, a competitive grin. She clutched her mallet and gave a masterful, steady swing. I watched her blood-red ball plunk forward, a perfect advance. I held my breath. The ball was still traveling toward the finish when I awoke.

SHE BROUGHT IN THE Ollie’s Daily and dropped it on the kitchen counter. “Rae, Love,” she called, “I’ve got good news for you!” Raelyn entered from the dining room where her homework was sprawled across the table. Her mother held page five in midair, peck-peck-pecking at the photo. “Ta-da!” she sang. “‘Investigators Give Compound A+!’”

Rae gazed at the newsprint. Curly, plump poodles posed on the page, as clean as newly fallen snow, each wearing a bright red ribbon. A picket fence in the foreground was set off by an array of colorful flowers. For a moment, everything went blank. Then a dizzying spiral of shadow and light engulfed the room.

“Rae? Raelyn!” the snap of her mother’s fingers appeared before her, and a sharp crease across her brow. “Honey? What just happened?”

Rae was leaning on the counter for support. “It’s not true. It’s not true, Mom.”

“What’s not true? What are you talking about?” Her mother’s voice was unusually slow and even.

“The photo. The dogs. It’s a lie. Or, or. . .a trick, or something.”

Ms. Devine placed a hand on her daughter’s shoulder and another on her forehead, feeling for clamminess or fever. Rae recoiled. “Honey, I know it’s been hard for you these past months. I know you miss her. It’s the Unknown, and it makes you think the worst. But it’s right here!” She again tapped at the newsprint. “This is what you—what we have waited to hear.”

“Stop it!” shouted Raelyn, covering her ears. “I’m telling you, it’s not—real!” She fled upstairs and slammed her door. How naive to have convinced herself that she could change the course of history.

The news article came up over dinner, but she couldn’t tell her parents how, or why, she was so certain about it. She saw the exchanges of concerned, our-daughter-needs-a-shrink glances. Smooth talk could not budge her.

“It’s proof they’re well cared for. It’s clearly a top-notch place,” her mother continued to assure her.

“Okay. If this place is so great, then why can’t we see it with our own eyes?” Rae demanded.

Her father was rereading the last paragraph. “It says here that it will be open for visitation in the late spring.”

“Yeah, and they said way back in January there’d be visiting, too. Remember? There will never be visiting hours. Or a release date. Trust me.”

“Honey, listen,” her mother said softly, “you can’t get this upset about every little thing in life. You’ll drive yourself crazy.” Then she smiled as if a new, exciting thought had just presented itself. “Have you ever heard about the glass half full? There’s a glass of water filled to the halfway mark. One person says, ‘The glass is half full.’ Another says, “The glass is half empty.’ They’re both right. But the optimist sees it in a positive way, and the pessimist sees it in a negative way.” When her daughter didn’t react, she continued, “You see? Please try to be positive.”

Her father was studying the dynamic between the two of them. He shared neither his wife’s half-full nor his daughter’s half-empty world view. But he was finding it more and more difficult to look his child in the eye. He turned the paper over and sipped his drink.

The following evening at the closed-door legislative session, he and the others sat in their unassigned but regular seats, with Chief Jerkins at the helm. His gestures mimicked Joan’s at dinner the day before, only his fingers were fatter, raising page five and tapping heartily at the fluffy pooches. “See there, friends?” His fleshy orange face burst with Glass Half-Fullness. “This ought to put a sock in it!”

Vigil studied his colleagues. Most were following the Leader, but Ms. Cronk’s eyes were lowered, and Mr. Morris looked out the window. Vigil shifted several times in his seat before redirecting his focus to Chief Jerkins, who was still pontificating about his successful solution to the Canine Problem.

“Excuse me.” All eyes turned to Vigil Devine. The room grew pin-drop still. “When does visitation begin?”

“Visitation?” The members turned to Jerkins.

“Yes.”

“Visitation?” Jerkins sneered again. His beady blue eyes made their rounds from face to face. Then his lips curled upward, showing the dimple on his left cheek.

Mr. Devine cleared his throat. “As I recall, the Compound was supposed to have visiting hours from the beginning. It’s been two and a half months. It’s a simple question: What date, precisely, does visitation begin?”

No one had ever before challenged the Chief on the issue. His sharp eyes drilled into Vigil’s, and his grin was replaced by a clenched jaw. As much as Vigil wished to turn away, he remained steadfast, unwavering. Mr. Pumpkin Head’s jaw relaxed, and his piercing stare broke. He looked calmly around the room, his brow raised in inquiry. “Ladies and Gentlemen of the Legislature,” he said in uncharacteristically low tone. “Does this gentleman have the floor?”

Pathetic “No, sirs” fluttered about, lashes downcast.

“I thought not.”

A prickle burned across Vigil’s forehead where it met his receding hairline. Beads of perspiration formed, dripping between his eyes and down the bridge of his nose. He mopped his face with a napkin. Cautious voices around the room addressed other items on the agenda, but he had lost the thread of the conversation. Within minutes, the meeting was adjourned.

That evening, he typed up his one sentence resignation letter, leaving the date blank. It read:

Dear Chief Jerkins:

I hereby resign my position in the Daffy County Legislature effective immediately.

Very truly yours,

Vigil W. Devine

He folded it and tucked it in the back reaches of his sock drawer until the time was right.

It didn’t take long. A heart-to-heart talk was long overdue with his soon-to-be twelve-year-old. The very next morning, he saw that she had hacked off all of her hair, leaving a dark, uneven mat at the scalp, begging to be noticed. What was happening? All he’d ever had to do was ask. She told him everything. She told him about the failed school club and Mr. E’s transfer. She told him about the secret bottom to the food pail and the bangs. She described everything she’d seen inside the Compound and told him about the photographs she’d taken, and her anonymous mailing to the Welfare Society—her last resort for help. The one detail she left out was that she had eaten dog food.

As he listened, Raelyn’s stature seemed to grow and his to shrink. She was like Alice, too large to fit into their house in Wonderland, and he, the diminutive toad in the shadow of a mushroom. From what had always been the child’s seat at the table, she dwarfed him. All the times she had approached them—seeking answers, begging for guidance, sobbing, arguing–-only to be met with his downcast stare. He’d had no idea she had done all those brave things: more evidence of just how asleep he’d been while awake and going through the motions. It had taken a garbage bag of curls to wake him up.

Finally, with a leap of trust, she confided in him about her latest plan—to rescue Penelope from that horrid place. She had the assistance of an unnamed fellow student, she warned, and no one was going to stop them. They could use a reliable grown-up in their corner.

After a long pause, even his voice seemed shadowed and small. “As an adult, I’d be facing twenty years in prison if I were caught there.” He shook his head. “I just can’t take that risk. For you or your mother. Or your brother.”

“We know. That’s why it’s going to be us kids.”

After another delay, he replied, “I’m concerned about your safety, Raelyn. We’re talking about real danger here.”

“We know that, too. We’re doing it anyway,” she announced. “We’re saving Penny.”

Enter Dad, newest member of the team. “How can I help,” he said at last.

Assembled around their dining room table three days later were Raelyn, her father, Gil, and Doc Goodman. Her mother was at work that evening, which was precisely why they were meeting then. They had agreed that she posed a danger to their plan. It wasn’t intentional on her part. Like so many others, it happened by osmosis—the hatred of the masses seeping into her mild disdain; the unconscious, gradual assimilation of ideas. In other words, she had become a canine foe.

She wouldn’t be home for another two hours.

They had only one opportunity to meet face-to-face to finalize the rescue plan for the following night. There could be no writing, no phone calls, texts, tweets, or emails. All those forms of communication were subject to confiscation. The secret police were onto certain people, and Doc Goodman was one of them. They would be tracking his movements, bugging his phone, intercepting and analyzing his computer activities. So far, the Devines were not on the radar. But just in case Doc had been followed there, a Scrabble board commanded the center of the table. To any outsider, it was harmless fun.

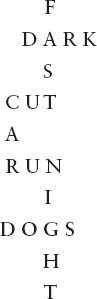

They had a full agenda. As real and dangerous as it was, Raelyn felt as if she were playing a game of Spy or cops and robbers. Her father cleared his throat. “I’ll start.” He placed three letter tiles on the center of the Scrabble board. They read, C-U-T. “First, the back fence of the Compound must be. . .CUT. . .in advance. That will be the point of ingress and egress.”

“What?” Gil asked.

“Entrance and exit.”

“C-U-T. That’s good, Dad!” Raelyn clapped for a few seconds until she noticed the somber expressions on the others and suddenly felt ridiculous and immature. This wasn’t a game, after all. She flicked the phantom hair off her shoulder, forgetting yet again that it wasn’t there.

“I’ll do that,” Doc volunteered. “I can’t risk being there for the actual rescue, but I’ll cut an opening in the fence.”

“Won’t they be following you?” Gil asked.

Doc paused. “You’re right.” He dangled his glasses in his hand. “. . .It’s my car they follow, really. I’ll drive to the supermarket, enter from the front and leave out the back door. I’ll have a cab take me close to the Compound, do my business, get back to the store and leave from the front with a grocery bag. I’ll wave to the undercover cop waiting for me in the parking lot and go home. How does that sound?”

“Sounds good. Risky, but good.” Vigil lifted the Scrabble board slightly and pulled Angie’s color-coded map from under it. He showed it to Doc and pointed to the far boundary opposite the front gate. “You’ll want to cut right about. . .here.” Doc nodded.

“And,” Gil offered, “you’ll have to get there, CUT the wire, and get back FAST,” he proudly added the F, A and S tiles above the “T” of CUT on the Board:

Hey, not bad, Gil,” Rae exclaimed. “And,” she jumped up, picking through the tiles, “make sure it’s D, A, R, K—DARK out.” She placed the D to the left of the A in FAST and the R and K to the right:

Her father smiled, then turned serious again. “Then I’ll take you two—” he looked at Rae and Gil—“to the Compound in my CAR.” He placed the new letters on the board:

“And I’ll park two blocks away on Spring Street, which is somewhere over here.” With his finger, he drew an invisible X off the upper right corner of Angie’s map. “You two will proceed by foot to the back of the premises and crawl under the cut fence over. . .here.”

“Got it,” Gil agreed.

“Got it,” Rae mimicked. “We’ll have to RUN!” The U and the N followed:

She continued, “and then we get Penelope. . .” but when she looked at the next word she’d created, her head sank into her hands.

“Raelyn?” her father asked softly.

She stared again at the word in front of her. It spelled, D-O-GS. “It’s all wrong. We can’t just save Penny and leave everyone else there.” She searched the intricacies of the Scrabble board. “We have to find a place for this.” The others gazed among each other and felt the heaviness of the room. She was right.

She also was right that D-O-G-S didn’t fit anywhere. “Let me help you out,” Doc offered. He selected a few letters and placed them on the board under the N in RUN. “The rescue must be completed before dawn, that is, at N, I, G, H, T—NIGHT.”

He turned to Rae. “Now, your DOGS.”

Rae lined her tiles along the G in NIGHT:

She continued the story: “Then Gil and I will round up Penny and all of the DOGS—from the barracks and—”

“And,” Gil interjected, “get them all to the back D,O,O,R — DOOR—where they’ll crawl out to freedom!” He and Rae exchanged high fives.

Vigil’s tone turned serious. “It won’t be easy, kids. You’ll be operating under strict time constraints. Saving every one of them is unrealistic.”

“But, Dad, we can’t leave anyone there. They’ll die.”

“Honey, shh. We’ll do our best. But we cannot promise a hundred percent success. Gil needs to get home before anyone misses him. And you both need to show up at school as usual.”

Gil was rearranging more letter tiles. “Seriously, Dad? Can’t you call in sick for us?”

He shook his head slowly. “I don’t think that would be wise.”

Doc Goodman agreed. “Remember, the night shift ends at seven o’clock, so the morning guards could arrive as early as 6:30.”

“Good point, Ken.” Vigil continued, “So you two must get back to the car by six o’clock at the very latest.” He shifted a stern eye from Rae to Gil. “No exceptions.”

“But we will rescue them all,” Rae insisted on the final word.

As it turned out, it really was the final word of the meeting, because just as she said it (a bit too loudly), the doorknob turned.

All four stared at her mother, Nurse Joan Robin Devine, in hospital scrubs. Gil and Rae’s jaws hung open like broken toys. Vigil’s hand instinctively slid Angie’s map under the Scrabble board.

“Mom! What are you doing here?”

“Um, I live here?” She surveyed the scene, suspicious. When was the last time they’d invited the veterinarian and an unfamiliar boy over for a game of Scrabble on a Wednesday night? “What’s going on here?” she demanded of her husband.

“We’re playing board games,” he replied, hoping it would be obvious. “Joan, this is Gil.”

“Nice to meet you, Mrs. Devine.” His voice was hoarse.

Doc Goodman slid the chair out next to him. “Care to join in?”

“No, no,” she said, “really.” She was studying the Scrabble Board. “Let’s see, what have we here? CUT, DOOR, NIGHT, DARK, DOGS, RUN, FAST, CAR. Interesting.” She looked directly at her husband.

He tried to change the subject. “You got off work early. That’s terrific.”

“It is terrific, isn’t it? Fortuitous, even.” She smiled ominously at each of them and locked longest on her daughter with the nearly shaven head. Rae swallowed hard. Then her mother turned to Gil. “Gil, is it?” Her eyes shifted to the row of tiles in front of him: “T, H, U, R, S—THURSday. Those can go right. . .here.” She moved her finger horizontally from the T along the column that spelled NIGHT. Gil tried to mutter a thank you, but there was no sound.

No one had a response to this wholly unexpected encounter. As complex as the rescue plans were, this confrontation by Ms. Devine was the most challenging moment yet. She spelled T-R-O-U-B-L-E. What had she meant that her arrival home was “fortuitous”? Why the sinister smile? All four of them suffered the same dreaded thoughts: Would she turn them in? She wouldn’t really have her own husband arrested, would she? Or Doc Goodman, who had risked his life for them only months ago to save Penelope from the fate she now faced?

Then again, Daffy County had gone mad. Neighbors turned on neighbors, friends turned on lifelong friends. And yes, family members not uncommonly turned on their own relatives. Vigil alone knew that, regrettably, his wife had done it once before—to her own son, no less.

Or, they wondered, would she keep their secret, look the other way? Rae recalled her mother sobbing, turning the pages of Penny’s photo album that first night amid a carpet of used tissues. There was no telling. One thing they did know was that they couldn’t count on her. Vigil made an executive decision. Their rescue mission could not wait until tomorrow night. It had to happen before sunrise.