ON the morning of the following Thursday, when Mrs Melhuish and Mrs Arndale called at the Riverside with a large quantity of chrysanthemums and solicitous inquiries for Colonel Gore, a stolid-visaged person who stated that he was the colonel’s man, took them over from Percival outside his master’s door peremptorily. The colonel was up that morning for the first time, he explained, and not quite dressed. The two ladies, however, declared that that didn’t matter in the least, and, though with obvious misgivings as to the propriety of the proceedings, he admitted them to the invalid’s sitting-room.

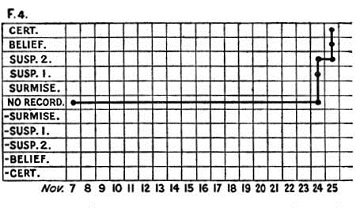

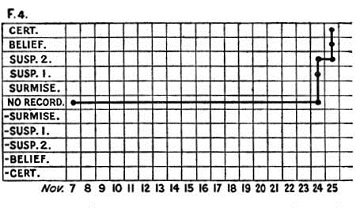

There they found Colonel Gore seated at his writing-table in a dressing-gown which he drew about him rather hurriedly upon their appearance, with a plaster-of-Paris-encased leg cocked up on an adjoining chair. When he had thanked them for their flowers, learned that Mrs Melhuish felt almost quite herself again, and that Mrs Arndale’s husband’s leg was progressing as satisfactorily as he assured them his own was, Mrs Melhuish bent with knitted brows to inspect a curious-looking diagram upon which he had apparently been working at the moment of their entry and which is here reproduced for the reader’s edification.

Mrs Melhuish, it has to be admitted, could make nothing of this document. Mrs Arndale said it reminded her of the performance of a what-do-you-call-it—not a barometer—but the other thing. Colonel Gore refused, with some trifling embarrassment, to explain it, and diverted the conversation to the chrysanthemums again.

Then for a little time they discussed the accident on the preceding Sunday morning. Mrs Melhuish couldn’t understand it. She had often noticed the Kinnairds’ chauffeur. Quite a superior-looking young man. She was sure the Kinnairds would not have kept him so long if they had thought him a reckless driver.

‘Do you think he had been drinking?’ she asked severely. ‘One would say he must have been either mad or drunk to have attempted to take that corner at such a speed. Perhaps he was just showing off.’

‘Perhaps so,’ Gore agreed.

‘Well, he paid dearly for it, poor fellow,’ said Mrs Arndale. Left a widow, I suppose. Was he married, dear?’

‘No,’ replied Mrs Melhuish, ‘thank goodness. Quite bad enough for Sidney to have his car smashed up, without having to pay a pension to a widow. Of course the car was insured—’

‘Oh, then, that’s all right,’ laughed Mrs Arndale cheerfully. ‘Now, my dearest Barbara, we must trot along. I’ve got to have a tooth stopped, run down a tweeny, and find Cecil a book he can read—all before lunch. Come along. See you sometime, Wick. Keep on getting better and better. By-bye.’

She waved a farewell from the door and was gone. Mrs Melhuish held out her hand.

‘I’m so glad you had it out with your husband, Pickles,’ smiled Gore. ‘By the way, I’ve got those letters for you.’

‘What?’

She hung towards him, still holding his hand. Her exquisite eyes filled slowly with a divine rapture. Her clear pallor warmed to the flush of a wild rose. ‘Get out,’ she whispered softly. ‘You’re pulling my leg.’

He averted his eyes hastily.

‘Fact,’ he said brightly. ‘They’re in there in my bedroom. I’ll send them across to you.’

‘Don’t,’ she smiled. ‘Burn them for me. Where did you—?’

‘Now—no questions,’ he commanded. ‘That is to be my reward.’

Mrs Arndale’s voice called her reproachfully from the corridor.

‘Very well,’ she smiled. ‘That … and this.’

She bent, kissed the thin spot on the top of his head, and fled laughing from the room.